Visual Abstract

Keywords: Complement; hemolytic uremic syndrome; pathogenic variants; Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome; complement factor H; human; Complement Factor H; Shiga Toxin; CD46 protein; human; Membrane Cofactor Protein; Escherichia coli; Genetic Background; High-Throughput Nucleotide Sequencing; Complement System Proteins; Complement Activation; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Genotype; Gene Frequency; Biomarkers

Abstract

Background and objectives

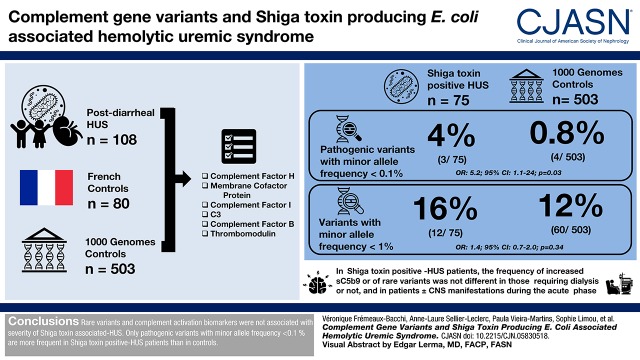

Inherited complement hyperactivation is critical for the pathogenesis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) but undetermined in postdiarrheal HUS. Our aim was to investigate complement activation and variants of complement genes, and their association with disease severity in children with Shiga toxin–associated HUS.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Determination of complement biomarkers levels and next-generation sequencing for the six susceptibility genes for atypical HUS were performed in 108 children with a clinical diagnosis of post-diarrheal HUS (75 Shiga toxin–positive, and 33 Shiga toxin–negative) and 80 French controls. As an independent control cohort, we analyzed the genotypes in 503 European individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project.

Results

During the acute phase of HUS, plasma levels of C3 and sC5b-9 were increased, and half of patients had decreased membrane cofactor protein expression, which normalized after 2 weeks. Variants with minor allele frequency <1% were identified in 12 Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS (12 out of 75, 16%), including pathogenic variants in four (four out of 75, 5%), with no significant differences compared with Shiga toxin–negative patients with HUS and controls. Pathogenic variants with minor allele frequency <0.1% were found in three Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS (three out of 75, 4%) versus only four European controls (four out of 503, 0.8%) (odds ratio, 5.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 24; P=0.03). The genetic background did not significantly affect dialysis requirement, neurologic manifestations, and sC5b-9 level during the acute phase, and incident CKD during follow-up. However, the only patient who progressed to ESKD within 3 years carried a factor H pathogenic variant.

Conclusions

Rare variants and complement activation biomarkers were not associated with severity of Shiga toxin–associated HUS. Only pathogenic variants with minor allele frequency <0.1% are more frequent in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS than in controls.

Introduction

Decreased C3 plasma levels at the acute phase of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) were first mentioned by 1973 (1–3). Forty years later, the demonstration that atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) was a disease of complement alternative pathway dysregulation (4), and that complement blockade therapy improved aHUS prognosis (5), gave a new impetus to the question of a role of complement activation in Shiga toxin–associated HUS. Indeed, elevated plasma levels of complement activation biomarkers were documented at the acute phase of post diarrheal/typical/Shiga toxin HUS (6–11). In vitro studies and animal models experiments demonstrated that Shiga toxin generates a cascade of endothelial/podocyte injury, complement activation, expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, neutrophil activation, and thrombus formation (7,12–18). The hypothesis of a genetic predisposition in Shiga toxin–associated HUS emerged in 2008, with the publication of a case of a 4-year-old girl with Shiga toxin–associated HUS, who died with a multiorgan failure syndrome and was found to carry pathogenic membrane cofactor protein variant (19). Altogether, 17 children with postdiarrheal/Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) HUS were subsequently reported who carried rare variants in complement genes (9,10,20–28). In nine of them, genetic screening was motivated by an unusually severe outcome, relapses, or post-transplant recurrence, suggesting that STEC infection triggers aHUS onset and/or preexisting complement variants amplify Shiga toxin–induced complement activation and endothelial/podocyte damage, and worsen disease severity (20–27). However, seven reported patients who had complement variants had a favorable outcome (9,10,28), leaving the issue of the role of genetics in Shiga toxin–associated HUS unclear.

The aim of our study was to investigate the frequency of rare variants in complement genes in a French national cohort of children with Shiga toxin–positive HUS compared with healthy controls, and the association of these variants with disease severity and complement activation biomarkers.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We enrolled 113 white children with a clinical diagnosis of postdiarrheal HUS, hospitalized in 22 pediatric nephrology departments between October 13, 2010 and October 17, 2012 (for study design, see Supplemental Material). We collected blood samples from 80 French controls (healthy white adult volunteers), to establish normal complement factors and sC5b-9 plasma levels and the frequency of complement variants in the French population. As a control/independent validation group, we collected the genotypes in the European individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project (n=503) (29) for the six genes of interest: complement factor H, factor I, factor B, membrane cofactor protein, C3, and thrombomodulin. The variant call format files located on the 1000 Genomes server (ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk) were parsed using the Ferret tool (30) to extract the genetic information of rare coding variants (minor allele frequency <1%). From the genotypes, we computed the occurrence of rare coding variants in each individual.

STEC Investigations

Patients were categorized as Shiga toxin–positive or Shiga toxin–negative, according to real-time PCR for Shiga toxin1 or Shiga toxin2 genes on stool samples (Supplemental Figure 1; for a list of STEC investigations, see Supplemental Material).

Genetic Screening

Exonic regions of six complement genes (factor H, factor I, factor B, membrane cofactor protein, C3, and thrombomodulin) were screened using next-generation sequencing. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was performed to detect factor H hybrid genes and complement factor H–related 1–3 genes deletion. The minor allele frequency of the genetic changes was obtained from the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org) (31). In our study, we defined a variant as rare when its minor allele frequency in the general population is <1% and as very rare when it is <0.1% (definitions adapted from Richards et al. [32] and Goodship et al. [33]). Among these rare variants, we named as pathogenic those for which the genetic change affects the protein function (well established in vitro functional studies supportive of a damaging effect on the gene product), and/or the genetic change is found in a disease-related functional domain or affects the protein expression (nonsense, frameshift, canonical ±1 or 2 splice sites variants, or well demonstrated lack of in vitro synthesis, or quantitative deficiency in the patient’s plasma) (adapted from Richards et al. [32] and Goodship et al. [33]). The other variants were classified as variants of uncertain significance. All patients’ parents gave informed consent for genetic analyses.

Complement Biomarkers

Assessment of CH50 (complement hemolytic 50), C3, C4, factor H, factor I, and sC5b-9 plasma level, membrane cofactor protein expression on leukocytes, and anti-factor H antibodies was performed in all patients (34). Results from blood samples collected under or after plasma infusions/exchanges (n=3) or eculizumab (n=6), or later than day 14 after admission (n=12), were excluded (Supplemental Figure 1).

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of patients are described with frequencies and percentages for categorical data, and with medians and interquartile ranges for quantitative data. Categorical data were compared using Fisher exact test, whereas quantitative data were compared using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney nonparametric test. All analyses (chi-squared, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U, and Fisher exact tests) with P value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

Among 113 patients, we identified 79 Shiga toxin–positive and 34 Shiga toxin–negative cases. Table 1 summarizes their clinical characteristics and outcomes. Antibiotic treatment during the prodromal phase was more frequent in Shiga toxin–negative (35%) than Shiga toxin–positive (18%) patients, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1 to 6.2; P=0.05). Central nervous system (CNS) manifestations were significantly more frequent in Shiga toxin–positive (23%) than Shiga toxin–negative (6%) patients (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1 to 21; P=0.03). Other characteristics during the acute phase and at last follow-up were similar between the two groups. No patient died during the follow-up. A single patient (Shiga toxin–positive) progressed to ESKD 3 years after HUS.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, in-hospital course, and outcome of 113 children with post-diarrheal HUS, with comparison of Shiga toxin–positive and Shiga toxin–negative patients

| Patient Characteristics | Stx-Positive HUS, n=79 | Stx-Negative HUS, n=34 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 2.6 (1.4; 4.9) | 3.4 (1.6; 5.5) |

| Sex, men/women | 38/41 | 17/17 |

| Prodromal phase | ||

| Gastrointestinal manifestations | ||

| Nonbloody diarrhea | 30 (38) | 14 (41) |

| Bloody diarrhea | 40 (51) | 19 (56) |

| Abdominal pain, vomiting, without diarrhea | 9 (11) | 1 (3) |

| Fever ≥38°C | 27 (34) | 15 (44) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection/otitis | 5 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Antibiotics | 14 (18) | 12 (35) |

| In-hospital | ||

| At admission | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 7.7 (6.3; 9.5) | 7.6 (6.1; 9.3) |

| Hemoglobin >9 g/dl | 25/77 (33) | 9 (26) |

| LDH, U/L | 3010 (2193; 4744) | 2619 (1151; 4056) |

| Platelet count, G/L | 40 (27; 56) | 48 (37; 77) |

| Leukocyte count, /mm3 | 13,070 (10,200; 20,030) | 12,400 (9535; 18,200) |

| Leukocyte count >20,000/mm3 | 18/69 (26) | 6/31 (19) |

| STEC investigations | ||

| Stool PCR for Stx | ||

| Stx1 positive | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Stx2 positive | 69 (87) | 0 |

| Stx1+Stx2 positive | 9 (11) | 0 |

| Stool culture | ||

| E. coli O157 | 37/77 (48) | 1a (3) |

| E. coli other than O157 | 25/77 (32) | 1a (3) |

| Nontypable E. coli | 10/77 (13) | 2a (6) |

| Anti-LPS serology | 33/64 (52) | 17/29 (59) |

| Positive | ||

| Clinical course | ||

| Anuria | 33 (42) | 12 (35) |

| Central nervous system manifestations | 18 (23) | 2 (6) |

| Prolonged intestinal manifestations | 22 (28) | 6 (18) |

| Pancreatitis | 11 (14) | 4 (12) |

| Cardiac manifestations | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment | ||

| Dialysis | 44 (56) | 14 (41) |

| Dialysis duration, d | 9 (4; 16) | 9 (7; 16) |

| Dialysis duration >8 d | 25/44 (57) | 10/14 (71) |

| Plasma infusion and/or plasma exchange | 8 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Eculizumab | 12 (15) | 3 (9) |

| Antibiotics | 27 (34) | 9 (26) |

| At last follow-up | ||

| Follow-up, mo | 46 (18; 65) | 53 (33; 61) |

| No CKDb | 52/73 (71) | 27/31 (87) |

| CKD stage 1b | 16/73 (22) | 2/31 (6) |

| CKD stage 2b | 1/73 (1) | 2/31 (6) |

| CKD stage 3b | 3/73 (4) | 0 |

| CKD stage 4b | 0 | 0 |

| CKD stage 5b | 1/73 (1) | 0 |

Values are shown as number (%) of patients or median (Q1; Q3). For items not documented in all patients, the number of documented patients is indicated and served for the calculation of the percentage indicated in brackets. No CKD was defined by eGFR≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 without albuminuria; CKD stage 1 by eGFR≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with albuminuria; CKD stage 2 by eGFR 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with albuminuria. See Supplemental Material for the definition of CKD stages 3–5 and albuminuria. HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; Stx, Shiga toxin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; STEC, Shiga toxin producing E. coli; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Non-Stx producing E. coli strains.

CKD stages according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines 2012 (http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/CKD/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf).

Complement Variants

In the whole cohort of patients with postdiarrheal HUS, we identified a total of 18 patients who carried one rare variant, all heterozygous, in factor H (n=3), membrane cofactor protein (n=1), factor I (n=1), C3 (n=8), factor B (n=1), thrombomodulin (n=3), or two variants (n=1) (Table 2). Among patients with Shiga toxin–positive or Shiga toxin–negative postdiarrheal HUS, a similar proportion (12 out of 75 [16%] and six out of 33 [18%], respectively (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3 to 2.5; P=0.8) carried one or two rare variants in one or two of the six tested genes, without significant difference in the frequency of the variants per gene (Table 2). The rare variants identified in patients are described in Table 3 and in Supplemental Table 1. Two variants (p.Ala382Glu in factor H gene and p.Asn170LysfsTer7 in membrane cofactor protein gene) were novel. As the factor H plasma level and membrane cofactor protein expression, respectively, were below normal ranges, the two corresponding variants were classified as pathogenic. Experimental functional investigations have shown that four variants are pathogenic as they lead to a reduced capacity to regulate alternative pathway activity (35–38). In total, six pathogenic variants were identified in Shiga toxin–positive (n=4) and Shiga toxin–negative (n=2) patients. Four of these variants were previously reported in aHUS (36,38) and one in STEC-HUS (24) (Table 3). Ten variants of uncertain significance were identified in Shiga toxin–positive (n=8) and Shiga toxin–negative (n=5) patients. Four of these variants of uncertain significance were previously reported in aHUS (39–44) and two in STEC-HUS (10,27) (Supplemental Table 1). Pathogenic rare variants identified in the two control cohorts are described in Supplemental Table 2. Four rare variants were found both in patients with HUS and French controls (Supplemental Table 3). Pathogenic variants were identified in 5%, 6%, 2%, and 3% of Shiga toxin–positive and Shiga toxin–negative patients, and of the French and European control cohorts, respectively (Table 4). Altogether, the frequency of rare variants per gene and per variant categorization was not significantly different between patients with HUS and controls and between Shiga toxin–positive and Shiga toxin–negative patients with HUS (Tables 2 and 4).

Table 2.

Number and frequency (%) of patients with post diarrheal HUS, and of French controls and European individuals included in the 1000 Genomes Project database, who carried rare variants in the six tested complement genes, or anti-factor H antibodies

| Complement Abnormalities | Postdiarrheal HUS, Total Cohort, n=108a | French Controls, n=80 | 1000 Genomes Controls, n=503 | Postdiarrheal HUS versus French Controls | Postdiarrheal HUS versus 1000 Genomes Controls | Stx-Positive HUS, n=75b | Stx-Negative HUS, n=33b | Stx-Positive versus Stx-Negative HUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | n (%) | n (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | |

| One rare variant per patient or control | ||||||||

| Complement factor H | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 8 (2) | 1.1; 0.2 to 6.8; >0.99 | 1.8; 0.5 to 6.8; 0.4 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.8; 0.1 to 10; >0.99 |

| Membrane cofactor protein | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 1 | 2.3; 0.2 to 26; 0.4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 |

| Complement factor I | 1 (0.9) | 2 (3) | 13 (3) | 0.3; 0 to 4; 0.5 | 0.3; 0.1 to 3; 0.4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 |

| C3 | 8d (7) | 4 (5) | 16 (3) | 1.5; 0 to 5; 0.5 | 2.4; 1 to 6; 0.05 | 5 (7) | 3 (9) | 0.7; 0.1 to 3; 0.7 |

| Complement factor B | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 7 (1) | 1 | 0.6; 0.8 to 5; >0.99 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombomodulin | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 2.2; 0.2 to 22; 0.6 | 1.6; 0.4 to 6; 0.4 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.8; 0.1 to 10; >0.99 |

| Two rare variants per patient or control | 1e (0.9) | 2f (3) | 5 (1) | 0.4; 0 to 4; 0.5 | 0.9; 0.1 to 8; >0.99 | 0 | 1 (3) | 0.1; 0 to 3.6; 0.3 |

| Total | 18 (17) | 11 (14) | 60 (12) | 1.2; 0.5 to 3; 0.6 | 1.5; 0.8 to 3; 0.1 | 12 (16) | 6 (18) | 0.8; 0.3 to 2.5; 0.8 |

| Anti-factor H antibodies | 3d (3) | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 2 | 0.2; 0 to 2.4; 0.2 |

HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; Stx, Shiga toxin; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Five of the 113 patients with HUS were not screened for variants in the six tested complement genes.

Four of the 79 patients with Stx-positive HUS and one of the 34 patients with Stx-negative HUS were not screened for variants in the six complement genes.

P with Fisher exact test.

One patient had a C3 rare variant and anti-Factor H antibodies.

This patient had a complement factor H and a C3 rare variant.

One control had a thrombomodulin and C3 rare variant, and another control had two rare variants in C3.

Table 3.

Complement pathogenic rare variants (n=6) found in six out of 108 patients with postdiarrheal HUS

| Patient | Gene | Variant | Genetic Status | No. of Patients | CFH Plasma Levela | MCP Expressiona | MAFb (%) | Demonstrated Functional Alterations | Previously Reported in STEC-HUS | Previously Reported in aHUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stx-positive patients with HUS | ||||||||||

| 1 | Complement factor H | c.2850G>T p.Gln950His | He | 1 | Normal | Normal | 0.36 | Moderately decreased binding to GAG and/or C3b (Hemolytic assay) (35) | Yes (24) | Yesc (38) |

| 2 | Thrombomodulin | c.1483C>T p.Pro495Ser | He | 1 | Normal | Normal | 0.06 | Decreased capacity to inactivate C3b (36) | No | Yes (36) |

| 3 | Complement factor H | c.1145C>A p.Ala382Glu | He | 1 | Low | Normal | Not found | Decrease FH level associated with C3 consumption (CFH deficiency)d | No | No |

| 4 | Membrane cofactor protein | c.503_504insA p.Asn170LysfsTer7 | He | 1 | Normal | Low | Not found | Decrease MCP expression (MCP deficiency)d | No | No |

| Stx-negative patients with HUS | ||||||||||

| 5 | Thrombomodulin | c.127G>A p.Ala43Thr | He | 1 | Normal | Normal | 0.34 | Decreased capacity to inactivate C3b (36) | No | Yes (36) |

| 6 | Complement factor H | c.3628C>T p.Arg1210Cyse | He | 1 | Normal | Normal | 0.017 | Alter the C3b/polyanions–binding site (37) | No | Yesc (38) |

HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; CFH, complement factor H; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; MAF, minor allele frequency; STEC, Shiga toxin producing E. coli; aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; He, heterozygous; GAG, glycosaminoglycans; FH, factor H.

At discharge.

MAF in Exome Aggregation Consortium database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/).

FH aHUS mutation database (http://www.fh-hus.org/).

V.F.-B., personal communication.

Patient 6 with CFH p.Arg1210Cys pathogenic rare variant also carried a C3 variant of uncertain significance.

Table 4.

Number and frequency (%) of patients with postdiarrheal HUS and of French controls and controls from the 1000 Genomes Project database, who carried at least one rare variant in one of the six tested complement genes

| Postdiarrheal HUS, Total Cohort, n=108a | French Controls, n=80b | 1000 Genomes Controls, n=503b | Patients with HUS versus French Controls | Patients with HUS versus 1000 Genomes Controls | Stx-Positive HUS, n=75c,d | Stx-Negative HUS, n=33c,e | Stx-Positive versus Stx-Negative HUS | Stx-Positive HUS versus 1000 Genomes Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuef | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuef | n (%) | n (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuef | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuef | |

| Individuals with a variant with MAF <1% | 18 (17) | 11 (14) | 60 (12) | 1.2; 0.5 to 3; 0.7 | 1.4; 0.8 to 2.6; 0.2 | 12 (16) | 6 (18.2) | 0.8; 0.3 to 2.5; 0.7 | 1.4; 0.7 to 2.9; 0.34 |

| Individuals with at least a pathogenic variant with MAF <1% | 6g (6) | 2h (2) | 14 (3) | 3; 0.4 to 12; 0.5 | 2; 0.8 to 5; 0.1 | 4 (5.3) | 2i (6.1) | 0.9; 0.2 to 5; >0.99 | 1.9; 0.6 to 6; 0.3 |

| Individuals with a VUS with MAF <1% | 12 (11) | 9h (11) | 46 (9) | 0.9; 0.4 to 2; >0.99 | 1.2; 0.6 to 2; 0.3 | 8 (10.7) | 4 (12.1) | 0.9; 0.2 to 3; >0.99 | 1.2; 0.5 to 3; 0.6 |

| Individuals with a pathogenic variant with MAF <0.1% | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.8) | 0.17 | 4.8; 1.2 to 19; 0.04 | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 1.3; 0.1 to 13; >0.99 | 5.2; 1.1 to 24; 0.03 |

HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; Stx, Shiga toxin; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Five of the 113 patients with postdiarrheal HUS were not screened for variants in the six tested complement genes.

All controls were screened for variants in the six tested complement genes.

Four of the 79 patients with Stx-positive HUS and one of the 34 patients with Stx-negative HUS were not screened for variants in the six complement genes.

Frequency of pathogenic variants with MAF <0.1% in Stx positive-HUS patients versus French controls: P=0.17.

Frequency of pathogenic variants with MAF <0.1% in Stx negative-HUS patients versus French controls: P=0.2; versus 1000 Genomes controls: OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 0.4 to 36; P=0.2.

P with Fisher exact test.

One of the six patients also carried a C3 VUS.

One control had a thrombomodulin pathogenic variant and a C3 VUS, and another control had two C3 VUS.

One of the two patients also carried a C3 VUS.

A very rare pathogenic variant with minor allele frequency <0.1% was identified in three out of 75 Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS (4%) (Table 3, cases 2, 3, and 4), compared with none of the 80 French controls (P=0.17) and four of the 503 European controls (0.8%) (OR, 5.2; 95% CI, 1.1 to 24; P=0.03) (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 2). We did not observe a significant difference in the very rare pathogenic variants between Shiga toxin–negative patients with HUS (one out of 33, 3%) (Table 3, case 6) and the French (P=0.2) or European control groups (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 0.4 to 36; P=0.2) (Table 4).

Homozygous factor H tgtgt or membrane cofactor protein ggaac haplotypes were found in 3% (three out of 97) and 6% (six out of 97) of patients with HUS, respectively. These frequencies were not significantly different from those in French controls (Supplemental Table 4). None of three patients with anti-factor H antibodies carried a homozygous complement factor H–related 1–complement factor H–related 3 deletion (Supplemental Table 5).

Complement Biomarkers during the Acute Phase

Median plasma levels of C3, factor I, and sC5b-9 were significantly higher, and median membrane cofactor protein expression significantly decreased in patients with HUS compared with French controls (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 6). C3 and C4 levels were significantly higher in Shiga toxin–negative compared with Shiga toxin–positive patients, whereas other changes were not significantly different between the two groups (Figure 1). No patient had C3 level below the lower limit of normal and only three patients had C3 levels close to the lower limit of normal (three out of 61, 5%) (Supplemental Table 7). The level of sC5b-9 was increased in 66% (38 out of 58) of Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS and membrane cofactor protein expression decreased in 57% (27 out of 47). Decreased membrane cofactor protein expression was significantly correlated with shorter delay of blood sampling (mostly within 4 days after admission) in Shiga toxin–positive patients (P=0.002; Figure 2A). In 11 documented patients, membrane cofactor protein expression normalized after HUS remission (Figure 2B). The level of sC5b-9 was not significantly correlated with delay in blood sampling within the first 14 days of admission or with leukocyte count (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Three patients had anti-factor H antibodies, at a low titer (<1000 AU/ml) (Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 1.

Increased C3, factor I and sC5b9 plasma levels and decreased membrane cofactor protein expression during the acute phase of postdiarrheal HUS. Median delay (First and third quartiles) of blood sampling after admission was 4 days (1; 6) (from admission to 13 days postadmission) for the total cohort, 2.5 days (1; 4.8) in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS, and 5.5 days (2.3; 9) in Shiga toxin–negative patients with HUS. Plasma samples collected under plasma infusion/plasma exchange (n=3) or eculizumab (n=6), or ≥14 days after admission (n=12) were excluded. See Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 7 for the number of patients studied. Results of the Mann–Whitney tests are indicated. FH, complement factor H; FI, complement factor I; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; Stx neg, Shiga toxin–negative; Stx pos, Shiga toxin–positive.

Figure 2.

Decreased membrane cofactor protein expression during the first days of Shiga toxin positive HUS. (A) Membrane cofactor protein expression in postdiarrheal HUS, according to delay between admission and blood sampling. MCP expression (normal range: 13–19 MFI, indicated between dashed lines) during the acute phase of HUS was documented in 56 Shiga toxin–positive patients (A1) and 26 Shiga toxin–negative patients (A2). It was below the lower limit of normal in 15 out of 20 (75%) and in four out of eight of Shiga toxin–positive or Shiga toxin–negative patients with HUS with blood sampling performed within 48 hours of admission, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients are indicated for each scatter plot. A linear relationship between MCP expression and the delay of blood sampling after admission was observed in Shiga toxin–positive HUS. (B) Normalization of MCP expression after remission (11 patients documented). Median (First and third quartiles) MCP expression was 10 MFI (8; 11) in hospital (9.6±2.1 days after admission) and 18 MFI (15; 21) after discharge (18.6±4.4 days after admission) (P<0.001 using paired samples t test). MCP, membrane cofactor protein; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Correlations between Complement Genetics, and Severity of HUS, sC5b-9 Levels during the Acute Phase, or CKD Stage at Last Follow-Up in Shiga Toxin–Positive Patients with HUS

The clinical characteristics and outcomes of the six patients with postdiarrheal HUS with pathogenic variants are presented in Table 5, and those of patients with C3 level at the lower limit of normal or anti-factor H antibodies in Supplemental Tables 5 and 7, respectively. The sC5b-9 level during the acute phase was not significantly different in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS with or without rare variant identified (Supplemental Figure 3). In Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS, the frequency of increased sC5b9, or of pathogenic variants, variants of uncertain significance or no variant identified was not different in patients requiring dialysis or not, in patients with and without CNS manifestations during the acute phase, and in patients with residual CKD stage 1–4 or CKD stage 5 compared with patients without kidney sequela (no CKD) at last follow-up (Table 6).

Table 5.

Clinical characteristics, in hospital course, and outcome of the six patients with postdiarrheal HUS, who carried complement pathogenic rare variants

| In-Hospital Course | Outcome | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. Sex, Age, yr | Genetic Complement Abnormalitiesa | C3b,c, mg/L | sC5b-9b,c, ng/ml | Stool Stx PCR (STEC Serogroup) | Hbc, g/dl | Pltc, /mm3 | WBCc, /mm3 | Screatc, mg/dl | Dialysis Duration, d | Systemic Manifestations | PI/PE and/or Eculizumab | Follow-up, yr | Sequelsd | Relapse |

| Stx-positive patients with HUS | ||||||||||||||

| 1. F, 2.6 | CFH, p.Gln950His | 975 | 479 | Stx2 positive (O157 in stool) | 9.8 | 81,000 | 25,600 | 6.1 | 25 | CNS | No | 5.8 | CKD stage 5 (ESKD) at 3 yr follow-up Kidney graft at 4 yr follow-up | No |

| 2. M, 2.0 | THBD, p.Pro495Ser | 1240 | 519 | Stx2 positive (O80 in stool) | 5.8 | 41,000 | 13,070 | 3.9 | 0 | None | No | 4.2 | No CKD | No |

| 3. F, 2.4 | CFH, p.Ala382Glu | 914 | 433 | Stx2 positive (O157 in stool) | 6.9 | 34,000 | 17,400 | 0.6 | 0 | None | No | 3 | No CKD | No |

| 4. M, 3.5 | MCP, p.Asn170LysfsTer7 | 1090 | 182 | Stx2 positive (ND) | 7.2 | 400,000 | 7200 | 0.9 | 0 | None | No | 4.8 | CKD stage 1 Proteinuria; eGFR 108 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | No |

| Stx-negative patients with HUS | ||||||||||||||

| 5. M, 13.5 | THBD, p.Ala43Thr | 1180 | 231 | Stx negative (stool culture and serology negative) | 5.0 | 59,000 | 7900 | 163 | 3 | None | No | 4.4 | No CKD | No |

| 6. M, 4.4e | CFH, p.Arg1210Cys+C3 p.Asp1440Ala VUS | 1210 | 557 | Stx negative (only O157 serology positive) | 5.8 | 30,000 | 9000 | 4 | 7 | Pancreatitis | No | 4.5 | No CKD | No |

HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; Stx, Shiga toxin; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli; Hb, hemoglobin; Plt, platelet count; WBC, white blood cell; Screat, serum creatinine; PI, plasma infusion; PE, plasma exchange; F, female; CFH, complement factor H; M, male; CNS, central nervous system; THBD, thrombomodulin; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

See Table 3.

Normal range: C3: 615–1250 mg/L; sC5b-9: <420 ng/ml; Conversion factor for serum creatinine from mg/dl to µmol/L: ×88.4.

At admission.

CKD stages according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines 2012 (http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/CKD/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf). See Supplemental Material for definition of CKD stages.

Patient 6’s first cousin had HUS 4 years after patient 6.

Table 6.

Severity of HUS according to sC5b-9 level and genetic background in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS

| Complement Abnormalities | Acute Phase | Last Follow-Upa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis Required | CNS Manifestations | No CKDb | CKD Stage 1–4b | CKD Stage 5b | CKD Stage 1–4 versus No CKD | CKD Stage 5 versus No CKD | |||||

| Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | OR; 95% CI; P-Valuec | |

| Increased sC5b-9 (>420 ng/ml)d | 23/33 (70) | 15/25 (60) | 1.5; 0.5 to 4.6; 0.2 | 11/13 (85) | 27/45 (60) | 3.6; 0.7 to 18; 0.1 | 25/36 (69) | 9/18 (50) | 1/1 (100) | 2.3; 0.7 to 7; 0.2 | 2.3; 0 to 19; 0.4 |

| Pathogenic variant (n=4) | 1/42 (2) | 3/33 (9) | 0.2; 0 to 2.4; 0.2 | 1/17 (6) | 3/58 (5) | 1.1; 0.1 to 12; 0.9 | 2/48 (4) | 1/20 (5) | 1/1 (100) | 0.8; 0.1 to 9; >0.99 | 55; 1.8 to 1747; 0.06 |

| Variant of uncertain significance (n=8) | 5/43 (12) | 3/32 (9) | 1.2; 0 to 5.8; 0.9 | 0/17 (0) | 8/58 (14) | 0.2; 0 to 3; 0.2 | 7/48 (15) | 1/20 (5) | 0/1 (0) | 3.2; 0.3 to 28; 0.4 | 0.5 |

| No variant identified | 37/43 (86) | 26/32 (81) | 1.4; 0 to 5; 0.3 | 1/17 (6) | 11/58 (19) | 0.3; 0 to 2.2; 0.2 | 39/48 (81) | 18/20 (90) | 0/1 (0) | 0.5; 0.1 to 2.5; 0.4 | 0.13 |

HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Median (First and third quartiles): 47 months (20–65) (n=79 with six lost to follow-up). The CKD stage was documented at 3 year follow-up in 43 patients.

CKD stages according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines 2012 (http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/CKD/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf). See Supplemental Material for definition of CKD stages. No patient had CKD stage 4 at last follow-up.

P with Fisher exact test.

Samples before day 14 after admission.

One of the four Shiga toxin–positive patients who carried a pathogenic variant progressed to ESKD within 3 years, compared with none of the 43 Shiga toxin–positive patients without pathogenic variant and with available clinical data 3 years after the acute episode (P=0.08).

Discussion

This is the largest case series describing the rare variants in complement genes identified in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS. We show that only very rare pathogenic variants with minor allele frequency <0.1% are more frequent in Shiga toxin–positive patients than in controls, which underscores the role of complement activation in Shiga toxin–associated HUS.

We used next-generation sequencing to screen the six genes implicated in aHUS pathogenesis, in 108 children with a clinical diagnosis of postdiarrheal HUS, including 75 children with Shiga toxin–positive HUS and 33 with Shiga toxin–negative HUS, and in 80 French controls. We found a rare variant in one or two genes in 16% of the Shiga toxin–positive patients, but only 5% of these patients carry a pathogenic variant previously demonstrated to lead to the impairment of complement regulatory activity (35–38). To categorize the clinical relevance of genetic findings, we first analyzed whether patients are enriched for complement rare variants compared with controls. We found a similar frequency of rare variants in the total cohort of 108 patients with HUS (17%), and in 80 French controls (14%) and 503 European individuals (12%), and no significant differences of variants’ frequency whatever the gene and the variant categorization (pathogenic or variant of uncertain significance) between Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS and French or 1000 Genomes Project controls. Still, when we focused our analysis on very rare pathogenic variants with minor allele frequency <0.1%, we showed that such very rare pathogenic variants were associated with a five-fold higher risk of developing Shiga toxin–positive HUS. Thus, although Shiga toxin–associated HUS is mostly driven by the infectious agent, our study highlights that in rare cases, genetic abnormalities may contribute to complement activation in Shiga toxin–associated HUS, consistent with published data (9,10,20–28). However, our study did not include patients with Shiga toxin infection who did not develop HUS (a study difficult to complete outside of large epidemics) and thus cannot prove the role of genetics in the risk of developing HUS after Shiga toxin infection.

We next hypothesized that the genetic background may influence the disease clinical course. We did not find significant differences in the frequency of CNS manifestations and dialysis requirement during the acute phase, or incident CKD after long-term follow-up in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS with complement pathogenic variants, variants of uncertain significance, or no variant. Still, the only patient who progressed to ESKD within 3 years carried a factor H pathogenic variant leading to functional factor H deficiency (patient 1, Table 5), previously identified in another patient with severe STEC-HUS rescued by plasma exchanges (24) (patient 1, Supplemental Table 8). It should, however, be mentioned that our patient presented with relatively high hemoglobin levels, leukocytosis, and neurologic manifestations during the acute phase, which are known risk factors for poor kidney outcome. Similarly, no recovery of kidney function was documented in one of six (16%) Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS who carried pathogenic variants reported in the literature (Supplemental Table 8). In unselected cohorts of STEC-HUS, only 1.4%–3% (45,46) of children progressed to ESKD within 4–5 years. In our relatively small cohort of Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS, we observed a trend (P=0.06) toward a significant correlation between the identification of a pathogenic variant and ESKD at last follow-up. However, the role of hereditary complement abnormalities needs to be confirmed by a large international study. Finally, considering our data and prior case reports of STEC infection unmasking complement deficiency, genetic screening does not appear justified for all patients with postdiarrheal HUS, but should be considered in patients with a fulminant course to death or ESKD (19,20,22,27), progression to ESKD within <3 years (patient 1, Table 5), a family history of HUS (23) (patient 6, Table 5), relapse of HUS (21,23,26), or post-transplant recurrence (22,27).

We observed significantly increased C3 and factor I median levels in Shiga toxin–positive patients, confirming prior reports (9,10). Except for significantly lower C3 and C4 levels in Shiga toxin–positive compared with Shiga toxin–negative patients, complement biomarkers did not differ between the two groups. Interestingly, C3 levels close to the lower limit of normal were observed in only three patients (5% of the cohort). Recent reports also observed slightly decreased C3 levels in only four out of 25 (9) and five out of 21 (10) patients with STEC-HUS, and exceptionally severely decreased level (one out of 21) (10). We confirm that 66% of Shiga toxin–positive patients have an increase of sC5b-9 level, the commonly used marker of terminal complement activation pathway, during the acute phase, as previously reported in 59%–64% (9,10) to 100% of patients (6–8). Our results do not support a link between complement activation at the acute phase and the presence of variants in complement genes, confirming that complement activation is predominantly a Shiga toxin–induced phenomenon. Complement biomarkers reflect the balance between increased synthesis related to inflammation and consumption related to complement activation (47). Increased sC5b-9 levels were not significantly correlated with higher frequency of dialysis requirement or CNS manifestations at the acute phase, as previously reported (6), or CKD at last follow-up. Therefore, our study did not support that C5 activation may be associated with STEC-HUS severity at the acute phase. However, our data do not allow taking position on the place of complement blockade therapy in STEC-HUS.

We show for the first time a significantly decreased membrane cofactor protein expression at the acute phase of Shiga toxin–positive HUS, correlated with shorter delay of blood sampling. In vitro studies have shown that Shiga toxin does not influence membrane cofactor protein expression on glomerular endothelial cells surface (48). Heme-induced decreased expression of membrane cofactor protein on cells, as reported in aHUS (49), is a more likely explanation. In practice, clinicians should be aware that decreased membrane cofactor protein expression during the acute phase of postdiarrheal HUS is not sufficient to conclude that the patient has aHUS related to a membrane cofactor protein variant, unless decreased expression persists after remission, as observed in one patient (patient 4, Table 5).

Our series also illustrates the limitations of STEC biologic investigations to classify patients as having typical HUS or aHUS. Positive or negative Shiga toxin screening is frequently used to support the diagnosis of Shiga toxin–associated HUS or aHUS (4), respectively, and this influences therapeutic decisions. In clinical practice, the challenge is whether patients with a clinical diagnosis of postdiarrheal HUS who have a negative Shiga toxin PCR should be classified as aHUS. Such patients in our cohort remain classified as postdiarrheal HUS with unproven Shiga toxin/STEC infection, possibly due to antibiotic treatment or late stool collection. Interestingly, 33% of children with aHUS (Shiga toxin/STEC negative) do not carry any complement variant and have an overall favorable outcome (50), similar to Shiga toxin–negative patients with postdiarrheal HUS in this study.

In conclusion, our results show an overall limited role of rare variants in complement genes in Shiga toxin–positive HUS. Still, genetic screening should be considered in postdiarrheal patients with HUS who progress rapidly to ESKD.

Disclosures

V.F.-B. and C.L. have received consultancy and/or lecture fees and/or travel support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals. V.F.-B. serves as coordinator of the scientific advisory board of Alexion M11-001 atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome international registry, and C.L. has served as coordinator for France for this registry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

V.F.-B., C.L., and A.-L.S.-L. designed the study. V.F.-B. and P.V.-M. performed the genetic screening and the complement assessment. S.L. analyzed the 1000 Genomes Project database. P.M. and F.-X.W. performed the Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli investigations. V.F.-B., P.V.-M., and C.L. analyzed the data. V.F.-B. and C.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to patients’ recruitment and clinical data collection, discussed the results, and contributed to the final manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (AOR 09 077 and AOM08198, to V.F.-B., A.-L.S.-L., and C.L.), by the European Union FP7 grant 2012-305608 (to V.F.-B., EURenOmics), the Fondation du rein (FRM Prix 2012 FDR, to V.F.-B.), and the Association pour l’Information et la Recherche dans les maladies Rénales génétiques (AIRG France).

We wish to acknowledge the following physicians who participated in the study: B. Boudailliez (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Amiens); L. Allard and G. Champion (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Angers); J. Harambat (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Bordeaux); L. Bessenay (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Clermont-Ferrand); G. Bourdat-Michel (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Grenoble); F. Lammens (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Lille); F. Garaix (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Marseille); M. Fila (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Montpellier); E. Allain-Launay (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Nantes); O. Boyer (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Hôpital Necker, Paris); C. Pietrement (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Reims); S. Taque and A. Ryckewaert (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Rennes); F. Broux and F. Louillet (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Rouen); M.P. Lavocat (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, St. Etienne); G. Parlier (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, St. Nazaire); J. Terzic and S. Menouer (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Strasbourg); and S. Cloarec (Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire, Tours).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.05830518/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Rare variants of uncertain significance identified in patients with postdiarrheal HUS.

Supplemental Table 2. Pathogenic rare variants identified in French controls and in controls from the 1000 Genomes Project database.

Supplemental Table 3. Rare variants identified both in French controls and in patients with postdiarrheal HUS.

Supplemental Table 4. Frequency of homozygous complement factor H tgtgt and membrane cofactor protein ggaac haplotypes in patients with postdiarrheal HUS compared with French controls.

Supplemental Table 5. Clinical characteristics, in-hospital course, and outcome of three patients with postdiarrheal HUS, who had anti-factor H antibodies.

Supplemental Table 6. Plasma levels of CH50, C3, C4, factor H, factor I, sC5b9, membrane cofactor protein expression, and anti-factor H antibodies at the acute phase of postdiarrheal HUS.

Supplemental Table 7. In-hospital course and outcome of three patients with postdiarrheal HUS, who had C3 plasma levels close to the lower limit of normal at admission.

Supplemental Table 8. Summary of 17 patients reported in the literature, who had postdiarrheal HUS and carried a complement rare variant.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients with postdiarrheal HUS included in the study.

Supplemental Figure 2. sC5b-9 plasma level according to (A) delay after admission and (B) leukocyte count.

Supplemental Figure 3. sC5b-9 plasma level during the acute phase in Shiga toxin–positive patients with HUS with (n=7) or without (n=49) rare variant identified.

References

- 1.Cameron JS, Vick R: Letter: Plasma-C3 in haemolytic-uraemic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet 2: 975, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan BS, Thomson PD, MacNab GM: Letter: Serum-complement levels in haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Lancet 2: 1505–1506, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robson WL, Leung AK, Fick GH, McKenna AI: Hypocomplementemia and leukocytosis in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Nephron 62: 296–299, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fakhouri F, Zuber J, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Loirat C: Haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 390: 681–696, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, Greenbaum LA, Babu S, Bedrosian C, Bingham C, Cohen DJ, Delmas Y, Douglas K, Eitner F, Feldkamp T, Fouque D, Furman RR, Gaber O, Herthelius M, Hourmant M, Karpman D, Lebranchu Y, Mariat C, Menne J, Moulin B, Nürnberger J, Ogawa M, Remuzzi G, Richard T, Sberro-Soussan R, Severino B, Sheerin NS, Trivelli A, Zimmerhackl LB, Goodship T, Loirat C: Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 368: 2169–2181, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thurman JM, Marians R, Emlen W, Wood S, Smith C, Akana H, Holers VM, Lesser M, Kline M, Hoffman C, Christen E, Trachtman H: Alternative pathway of complement in children with diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1920–1924, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ståhl AL, Sartz L, Karpman D: Complement activation on platelet-leukocyte complexes and microparticles in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 117: 5503–5513, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraris JR, Ferraris V, Acquier AB, Sorroche PB, Saez MS, Ginaca A, Mendez CF: Activation of the alternative pathway of complement during the acute phase of typical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 181: 118–125, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahlenstiel-Grunow T, Hachmeister S, Bange FC, Wehling C, Kirschfink M, Bergmann C, Pape L: Systemic complement activation and complement gene analysis in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli-associated paediatric haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 1114–1121, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westra D, Volokhina EB, van der Molen RG, van der Velden TJ, Jeronimus-Klaasen A, Goertz J, Gracchi V, Dorresteijn EM, Bouts AH, Keijzer-Veen MG, van Wijk JA, Bakker JA, Roos A, van den Heuvel LP, van de Kar NC: Serological and genetic complement alterations in infection-induced and complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 297–309, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady TM, Pruette C, Loeffler LF, Weidemann D, Strouse JJ, Gavriilaki E, Brodsky RA: Typical Hus: Evidence of acute phase complement activation from a daycare outbreak. J Clin Exp Nephrol 1: 11, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orth D, Khan AB, Naim A, Grif K, Brockmeyer J, Karch H, Joannidis M, Clark SJ, Day AJ, Fidanzi S, Stoiber H, Dierich MP, Zimmerhackl LB, Würzner R: Shiga toxin activates complement and binds factor H: Evidence for an active role of complement in hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Immunol 182: 6394–6400, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morigi M, Galbusera M, Gastoldi S, Locatelli M, Buelli S, Pezzotta A, Pagani C, Noris M, Gobbi M, Stravalaci M, Rottoli D, Tedesco F, Remuzzi G, Zoja C: Alternative pathway activation of complement by Shiga toxin promotes exuberant C3a formation that triggers microvascular thrombosis. J Immunol 187: 172–180, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locatelli M, Buelli S, Pezzotta A, Corna D, Perico L, Tomasoni S, Rottoli D, Rizzo P, Conti D, Thurman JM, Remuzzi G, Zoja C, Morigi M: Shiga toxin promotes podocyte injury in experimental hemolytic uremic syndrome via activation of the alternative pathway of complement. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1786–1798, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway EM: HUS and the case for complement. Blood 126: 2085–2090, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betzen C, Plotnicki K, Fathalizadeh F, Pappan K, Fleming T, Bielaszewska M, Karch H, Tönshoff B, Rafat N: Shiga toxin 2a-induced endothelial injury in hemolytic uremic syndrome: A Metabolomic Analysis. J Infect Dis 213: 1031–1040, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos MV, Mejias MP, Sabbione F, Fernandez-Brando RJ, Santiago AP, Amaral MM, Exeni R, Trevani AS, Palermo MS: Induction of neutrophil extracellular traps in Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Innate Immun 8: 400–411, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoja C, Buelli S, Morigi M: Shiga toxin triggers endothelial and podocyte injury: The role of complement activation [published online ahead of print December 6, 2017]. Pediatr Nephrol 10.1007/s00467-017-3850-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang CJ, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Liszewski MK, Pianetti G, Noris M, Goodship TH, Atkinson JP: Membrane cofactor protein mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), fatal Stx-HUS, C3 glomerulonephritis, and the HELLP syndrome. Blood 111: 624–632, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edey MM, Mead PA, Saunders RE, Strain L, Perkins SJ, Goodship TH, Kanagasundaram NS: Association of a factor H mutation with hemolytic uremic syndrome following a diarrheal illness. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 487–490, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, Mossali C, Pianetti G, Gamba S, Daina E, Fenili C, Castelletti F, Sorosina A, Piras R, Donadelli R, Maranta R, van der Meer I, Conway EM, Zipfel PF, Goodship TH, Remuzzi G: Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1844–1859, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberti M, Valoti E, Piras R, Bresin E, Galbusera M, Tripodo C, Thaiss F, Remuzzi G, Noris M: Two patients with history of STEC-HUS, posttransplant recurrence and complement gene mutations. Am J Transplant 13: 2201–2206, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellier-Leclerc AL, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Dragon-Durey MA, Macher MA, Niaudet P, Guest G, Boudailliez B, Bouissou F, Deschenes G, Gie S, Tsimaratos M, Fischbach M, Morin D, Nivet H, Alberti C, Loirat C; French Society of Pediatric Nephrology : Differential impact of complement mutations on clinical characteristics in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2392–2400, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCoy N, Weaver DJ Jr.: Hemolytic uremic syndrome with simultaneous Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli and complement abnormalities. BMC Pediatr 14: 278, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caillaud C, Zaloszyc A, Licht C, Pichault V, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Fischbach M: CFH gene mutation in a case of Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS). Pediatr Nephrol 31: 157–161, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Challis RC, Araujo GS, Wong EK, Anderson HE, Awan A, Dorman AM, Waldron M, Wilson V, Brocklebank V, Strain L, Morgan BP, Harris CL, Marchbank KJ, Goodship TH, Kavanagh D: De novo deletion in the regulators of complement activation cluster producing a hybrid complement factor H/Complement Factor H-Related 3 gene in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1617–1624, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowen F, Wood K, Brown AL, Palfrey J, Kavanagh D, Brocklebank V: Rare genetic variants in Shiga toxin-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome: Genetic analysis prior to transplantation is essential. Clin Kidney J 10: 490–493, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardissino G, Salardi S, Colombo E, Testa S, Borsa-Ghiringhelli N, Paglialonga F, Paracchini V, Tel F, Possenti I, Belingheri M, Civitillo CF, Sardini S, Ceruti R, Baldioli C, Tommasi P, Parola L, Russo F, Tedeschi S: Epidemiology of haemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Data from the North Italian HUS network. Eur J Pediatr 175: 465–473, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR; 1000 Genomes Project Consortium : A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526: 68–74, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Limou S, Taverner AM, Winkler CA: Ferret: A user-friendly Java tool to extract data from the 1000 Genomes Project. Bioinformatics 32: 2224–2226, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG; Exome Aggregation Consortium : Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536: 285–291, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee : Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17: 405–424, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodship TH, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, Fervenza FC, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Kavanagh D, Nester CM, Noris M, Pickering MC, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Roumenina LT, Sethi S, Smith RJ; Conference Participants : Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: Conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 91: 539–551, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Dragon-Durey MA, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Sautes-Fridman C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V: Alternative complement pathway assessment in patients with atypical HUS. J Immunol Methods 365: 8–26, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohlin FC, Nilsson SC, Levart TK, Golubovic E, Rusai K, Müller-Sacherer T, Arbeiter K, Pállinger É, Szarvas N, Csuka D, Szilágyi Á, Villoutreix BO, Prohászka Z, Blom AM: Functional characterization of two novel non-synonymous alterations in CD46 and a Q950H change in factor H found in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome patients. Mol Immunol 65: 367–376, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delvaeye M, Noris M, De Vriese A, Esmon CT, Esmon NL, Ferrell G, Del-Favero J, Plaisance S, Claes B, Lambrechts D, Zoja C, Remuzzi G, Conway EM: Thrombomodulin mutations in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 361: 345–357, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Barricarte R, Pianetti G, Gautard R, Misselwitz J, Strain L, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Goodship T, Noris M, Remuzzi G, de Cordoba SR; European Working Party on the Genetics of HUS : The complement factor H R1210C mutation is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 639–646, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osborne AJ, Breno M, Borsa NG, Bu F, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Gale DP, van den Heuvel LP, Kavanagh D, Noris M, Pinto S, Rallapalli PM, Remuzzi G, Rodríguez de Cordoba S, Ruiz A, Smith RJH, Vieira-Martins P, Volokhina E, Wilson V, Goodship THJ, Perkins SJ: Statistical validation of rare complement variants provides insights into the molecular basis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy. J Immunol 200: 2464–2478, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Miller EC, Liszewski MK, Strain L, Blouin J, Brown AL, Moghal N, Kaplan BS, Weiss RA, Lhotta K, Kapur G, Mattoo T, Nivet H, Wong W, Gie S, Hurault de Ligny B, Fischbach M, Gupta R, Hauhart R, Meunier V, Loirat C, Dragon-Durey MA, Fridman WH, Janssen BJ, Goodship TH, Atkinson JP: Mutations in complement C3 predispose to development of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 112: 4948–4952, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brackman D, Sartz L, Leh S, Kristoffersson AC, Bjerre A, Tati R, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Karpman D: Thrombotic microangiopathy mimicking membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3399–3403, 2011. [Erratum in Nephrol Dial Transplant 32:584, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsson SC, Karpman D, Vaziri-Sani F, Kristoffersson AC, Salomon R, Provot F, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Trouw LA, Blom AM: A mutation in factor I that is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome does not affect the function of factor I in complement regulation. Mol Immunol 44: 1835–1844, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Békássy ZD, Kristoffersson AC, Cronqvist M, Roumenina LT, Rybkine T, Vergoz L, Hue C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Karpman D: Eculizumab in an anephric patient with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and advanced vascular lesions. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2899–2907, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pérez-Caballero D, González-Rubio C, Gallardo ME, Vera M, López-Trascasa M, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Sánchez-Corral P: Clustering of missense mutations in the C-terminal region of factor H in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 68: 478–484, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schramm EC, Roumenina LT, Rybkine T, Chauvet S, Vieira-Martins P, Hue C, Maga T, Valoti E, Wilson V, Jokiranta S, Smith RJ, Noris M, Goodship T, Atkinson JP, Fremeaux-Bacchi V: Mapping interactions between complement C3 and regulators using mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 125: 2359–2369, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosales A, Hofer J, Zimmerhackl LB, Jungraithmayr TC, Riedl M, Giner T, Strasak A, Orth-Höller D, Würzner R, Karch H; German-Austrian HUS Study Group : Need for long-term follow-up in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome due to late-emerging sequelae. Clin Infect Dis 54: 1413–1421, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spinale JM, Ruebner RL, Copelovitch L, Kaplan BS: Long-term outcomes of Shiga toxin hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 2097–2105, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Exeni RA, Fernandez-Brando RJ, Santiago AP, Fiorentino GA, Exeni AM, Ramos MV, Palermo MS: Pathogenic role of inflammatory response during Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Pediatr Nephrol 33: 2057–2071, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ehrlenbach S, Rosales A, Posch W, Wilflingseder D, Hermann M, Brockmeyer J, Karch H, Satchell SC, Würzner R, Orth-Höller D: Shiga toxin 2 reduces complement inhibitor CD59 expression on human renal tubular epithelial and glomerular endothelial cells. Infect Immun 81: 2678–2685, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frimat M, Tabarin F, Dimitrov JD, Poitou C, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT: Complement activation by heme as a secondary hit for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 122: 282–292, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Fakhouri F, Garnier A, Bienaimé F, Dragon-Durey MA, Ngo S, Moulin B, Servais A, Provot F, Rostaing L, Burtey S, Niaudet P, Deschênes G, Lebranchu Y, Zuber J, Loirat C: Genetics and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: A nationwide French series comparing children and adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 554–562, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.