Summary

Objective

The aim of this paper is to describe the results obtained from the application of a specific local deprivation index, to general and cause-specific mortality and influenza vaccination coverage among elderly people in the municipality of Florence.

Methods

General and cause-specific mortality data (2009-2013) and influenza vaccination coverage data (2015/16 and 2016/17) were collected for subjects aged ≥ 65 years residing in the municipality of Florence (Tuscany), at the 2011 Census section level. A Socio-Economic and Health Deprivation Index (SEHDI) was constructed and validated by means of socio-economic indicators and mortality ratios.

Results

Half of the population of Florence belonged to the medium deprivation group; about 25% fell into the two most deprived groups, and the remaining 25% were deemed to be wealthy. Elderly people mostly belonged to the high deprivation group. All-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality (cancer and respiratory diseases) reached their highest values in the high deprivation group. Influenza vaccination coverage (VC) was 54.7% in the 2015/16 and 2016/17 seasons, combined. VC showed a linear rising trend as deprivation increased and appeared to be correlated with different factors in the different deprivation groups.

Conclusions

As socio-economic deprivation plays an important role in health choices, application of the SEHDI enables us to identify the characteristics of the main sub-groups of the population with low adherence to influenza vaccination. The results of the present study should be communicated to General Practitioners, in order to help them to promote influenza vaccination among their patients.

Key words: Deprivation index, Mortality, Influenza vaccination, Elderly, Tuscany (Italy)

Introduction

Tuscany, an Italian Region with a population of 3,742,437 [1], is composed of 10 Provinces and 276 Municipalities. Florence, the capital city of Tuscany, is situated in the north of the Region and is the most populous city. In the municipality of Florence, the population grew from 358,079 in 2011 [2] to 382,258 in 2017 [1]. Elderly people, i.e. aged ≥ 65, account for about a quarter of the whole population (25.5% in 2011 and 25.8% in 2017) [1]. The age pyramid shows that people older than 80 years are more frequently widows or widowers, a condition that is more frequent among women [3]. With regard to the structural indicators of the population, in 2017 the ageing index was 214.8 and the old-age dependency ratio was 41.5 [4].

According to 2001 Census data, the areas with the highest percentages of deprived and highly deprived people are those on the western side of Florence and the area south of the River Arno. By contrast, the north-eastern area of the city has the lowest percentage of deprived and highly deprived people [5]. In a recent analysis performed in 2012, the percentage of people living in deprived or highly deprived areas of the city was 37.2%, lower than the average Tuscan value (40%) [5].

The main causes of death are cardiovascular diseases (36.1%) and cancer (28.9%). Other significant causes of death are respiratory tract diseases, nervous system diseases, injuries and gastrointestinal diseases. Cumulatively, the six above-mentioned leading causes of death account for more than 87% of all deaths [5].

In the Local Health Unit of Florence, the standardized mortality ratio in the years 2013-2015 was 8.7/1000: specifically, 10.9/1000 in males and 7.2/1000 in females. The standardized PYLL (potential years of life lost) rate was 33.03 (32.8-33.3) and the age-standardised avoidable mortality rate was 176.3/100,000 (166.7/100,000-185.8/100,000) [6].

With regard to socio-economic aspects, in 2017 the total unemployment rate in the Province of Florence stood at 6.8% [7]. This value has shown an increasing trend over the last ten years, but it remains lower than the regional Tuscan unemployment rate. The highest values are those among young people aged 15-24, whose unemployment rate was 16.4% in 2017. The employment rate of the 15-64 age-group was 69.3% in 2017 [7, 8].

Here, we report the results obtained from the application of the deprivation index to mortality and influenza vaccination coverage among people over 65 years of age according to the 2011 Census data on the municipality of Florence.

Methods

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee in September 2016, and data collection was authorized to start in October 2016. Moreover, in order to enable the analysis of coverage data collected by General Practitioners (GPs) in Florence in October 2017, a scientific collaboration agreement between the Local Health Unit of Central Tuscany and the Department of Health Sciences (University of Florence) was approved. The study population comprised subjects aged ≥ 65 years residing in the municipality of Florence (Tuscany) who had undergone influenza vaccination by their GPs.

The work was carried out according to the following phases:

-

Phase 1: collection of mortality data.

General and cause-specific mortality data were obtained from the Regional Mortality Registry (RMR) for the years 2009-2013, by gender and by two age-groups (0-64y and over 65y). A shared procedure of data exchange was established between the Municipal Statistical Office and the RMR, in order to assign each deceased person to the corresponding 2011 Census section. In this first phase of the data collection, the following steps were followed:

the RMR provided the Florence Municipal Statistical Office with a list of names (name, surname, date of birth and fiscal code, accompanied by an identifier code constructed ad hoc for the study) of all the residents of the Municipality of Florence who had died in the period 2009-2013;

the Florence Municipal Statistical Office assigned each subject on the list provided by the RMR to a census section by using two linkages, one for the name and date of birth and one for the fiscal code. The Statistical Office then sent a file containing only the following information to the RMR: the identifier code and the census section to which the subject had been assigned;

the RMR then provided the mortality data regarding the variables listed above: all causes and specific causes of death, by sex, two age-classes (0-64; 65+), year and census section. This information was then transmitted by the RMR to the local study manager and, in aggregate form, to the Project Coordinator.

-

Phase 2: collection of influenza immunization coverage data.

During the second phase, the following steps were followed:

collection of the number of subjects aged ≥ 65 years vaccinated during the 2015/16 and 2016/17 influenza vaccination campaigns by each GP in Florence. These data were obtained through the computer files containing the list of vaccinated patients, available at the Florence Health District;

identification of the address of the main outpatient clinic served by each GP. This information was used as a proxy of the geographical area of each GP, and was obtained from the database containing information on all GPs in Florence;

the address of each GP’s main clinic was linked to the corresponding census section (geocoding), after the list of all the addresses and their corresponding 2011 Census sections had been obtained from the Statistical Service of the Municipality of Florence;

calculation of the vaccination coverage (VC) in each census section. The total number of patients aged ≥ 65 years vaccinated by each GP was obtained from the database containing information on all GPs in Florence.

The total number of GPs was 260 in the 2015/16 season and 266 in the 2016/17 season. The difference between the two years was due to the different numbers of GPs retiring and of those starting work.

A local Socio-Economic and Health Deprivation Index (SEHDI) was developed according to the methodology proposed by Lillini et al. [9]. Three main factors made up the index and provided the best profiles of socio-economic-health inequalities in Florence; these factors explained 60.7% of the total variance.

To test the accuracy of the SEHDI, a validation procedure using socio-economic indicators and mortality ratios was performed [9].

Results

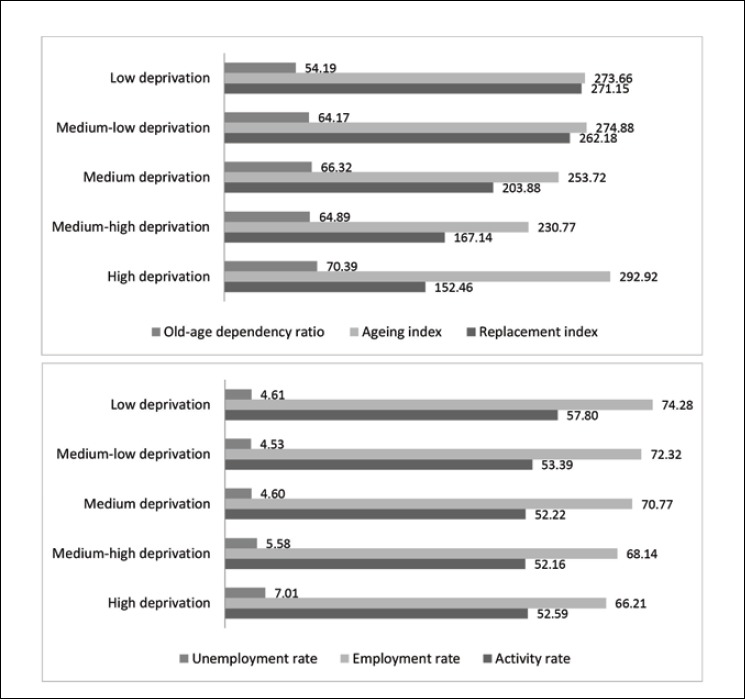

Regarding the socio-economic validation of the SEHDI, Figure 1 shows the main socio-economic status indexes for each deprivation group.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of socio-economic status indexes in the five deprivation groups.

Half of the population of Florence belonged to the medium deprivation group. About 25% fell into the two most deprived groups, and the remaining 25% were deemed to be wealthy. The least deprived groups were seen to live in the city centre area, while the north-western area of the city had the highest percentage of deprived residents. Elderly people mostly belonged to the high deprivation group, which showed the highest ageing index value (292.92).

The unemployment rate varied from 4.53 to 7.01, with the highest value in the high deprivation group. Accordingly, the employment rate was highest (74.28) in the low deprivation group, as was the activity rate (57.80).

Concerning mortality ratios, Table I shows the general and cause-specific mortality ratios in each deprivation group. Cause-specific mortality was analysed with regard to the following diseases: cancer (general and sex-specific) and respiratory tract diseases (including pneumonia and COPD).

The RMR recorded a total of 22,563 deaths among residents of the municipality of Florence in the period 2009-2013. Of these, 22,032 deaths were linked to the 2011 census sections and included in the analysis; this figure, which corresponded to 97.6% of the total number of deaths, was obtained after electronic and manual cross-check and data validation.

All-cause mortality and cancer-related mortality showed a non-linear trend, with the highest values in the high deprivation group; the respiratory disease-specific mortality rate displayed a linear trend, with the highest value in the high deprivation group.

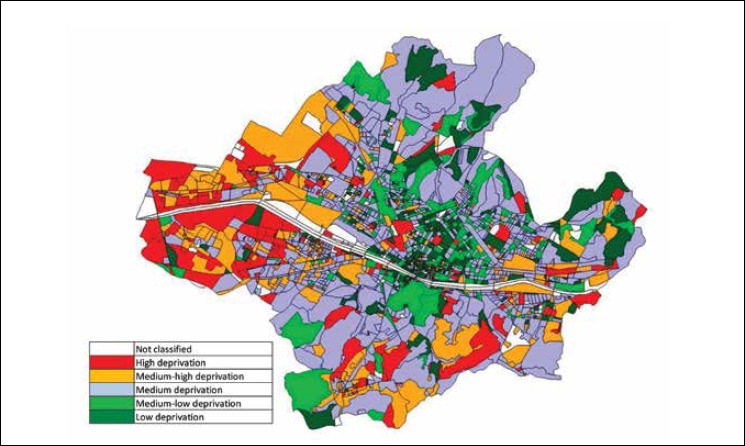

Regarding the distribution of the SEHDI by census section, the analysis showed that high deprivation was concentrated mainly on the western side of the city. The central area (north and south of the river) was the least deprived (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of deprivation indexes in the Municipality of Florence, by census section.

After application of the “linkage procedure” between the census section and the VC of each GP’s main outpatient clinic, the overall average VC was calculated to be 54.7% in the 2015/16 and 2016/17 seasons, combined; specifically: 57.3% in the 2015/16 season and 53.8% in 2016/17.

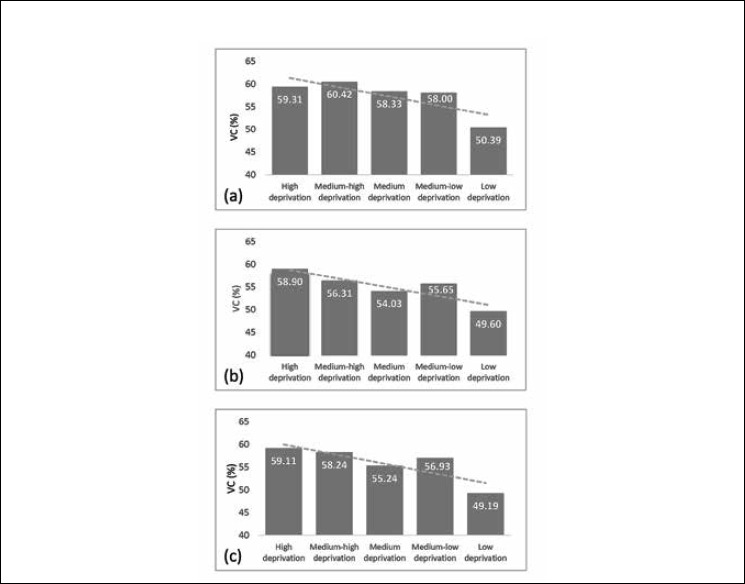

The results showed a linear rising trend in VC as deprivation increased (Fig. 3A-3C), which means that elderly subjects in the highly deprived group were more likely to be vaccinated than those in the least deprived group.

Fig. 3:

Influenza vaccination coverage (%) in the different deprivation groups:

a): Season 2015/16; b): Season 2016/17; c): Seasons 2015/16 and 2016/17 combined.

Concerning the 2015/16 season, a positive correlation emerged between VC and the percentage of married people, of people with lower secondary education, and of 2-member families. By contrast, a negative correlation was seen between VC and the percentage of singles/unmarried, of unemployed people looking for new jobs, of foreigners and stateless persons residing in Italy, of 1-member families and of unemployment.

In the 2016/17 season, a positive correlation was observed between VC and the percentage of married people, of 2- and 4-member families, and the average number of people per occupied dwelling. VC displayed a negative correlation with the percentage of separated and divorced people, of people belonging to the labour force, of unemployed people looking for new jobs, of term contract workers, and of temporary jobs.

Finally, in the whole period (2015/17), a positive correlation emerged between VC and the percentage of married people and of 2- and 4-member families, and the average number of people per dwelling. A negative correlation was seen between VC and the percentage of divorced people, of people belonging to the labour force, of unemployed people and of temporary jobs.

On examining the individual census variables, it emerged that VC correlated with different factors in the different deprivation groups (Tab. II).

Tab. II.

Factors influencing vaccination coverage in each deprivation group (with correlation values and statistical significance).

| Season 2015/16 | Pearson correlation | P value |

|---|---|---|

| High deprivation | ||

| % singles/unmarried | -1.000 | 0.020 |

| % upper secondary school | 0.997 | 0.046 |

| % earners from labor or capital income | 0.998 | 0.042 |

| % 2-member families | -0.999 | 0.026 |

| % single-parent families with children under 15 years | -0.998 | 0.042 |

| % single-member families 65+ | 0.999 | 0.031 |

| Medium-high deprivation | ||

| % 3-member families | 0.597 | 0.011 |

| Medium deprivation | ||

| % singles/unmarried | -0.408 | 0.007 |

| % married | 0.342 | 0.025 |

| % foreigners and stateless persons residing in Italy | -0.329 | 0.031 |

| % rented homes | -0.351 | 0.021 |

| % owned homes | 0.323 | 0.034 |

| % employees | 0.311 | 0.043 |

| % temporary job | -0.329 | 0.031 |

| Medium-low deprivation | ||

| % belonging to labor force | -0.572 | 0.032 |

| % employed | -0.541 | 0.046 |

| % not belonging to the labor force | 0.662 | 0.010 |

| % students | 0.548 | 0.042 |

| % earners from labor or capital income | 0.601 | 0.023 |

| % employees | -0.638 | 0.014 |

| Average area of homes occupied | 0.542 | 0.045 |

| Activity rate | -0.635 | 0.015 |

| Low deprivation | ||

| No correlation | ||

| Season 2016/17 | Pearson correlation | P value |

| High deprivation | ||

| % lower secondary school | 0-.995 | 0.043 |

| % unemployed looking for new jobs | -0.999 | 0.033 |

| % employed | -0.999 | 0.026 |

| % self employed | 0.994 | 0.041 |

| Activity rate unemployed looking for new jobs | -0.998 | 0.039 |

| Unemployment rate | -1.000** | 0.006 |

| Medium-high deprivation | ||

| % 3-member families | 0.458 | 0.044 |

| Medium deprivation | ||

| % divorced | -0.292 | 0.048 |

| % primary school diploma | -0.279 | 0.041 |

| % unemployed looking for new jobs | -0.355 | 0.024 |

| % self-employed | 0.355 | 0.025 |

| % single-parent families with children under 15 years | -0.314 | 0.048 |

| Unemployment rate | -0.315 | 0.048 |

| Medium-low deprivation | ||

| % housewives | -0.566 | 0.044 |

| % 3-member families | 0.617 | 0.025 |

| Low deprivation | ||

| % married | 0.476 | 0.025 |

| % separated | -0.380 | 0.041 |

| % rented homes | -0.379 | 0.082 |

| % 2-member families | 0.447 | 0.037 |

| % 3-member families | -0.405 | 0.041 |

| % term contract workers | -0.403 | 0.043 |

| % temporary job | -0.659* | 0.001 |

| Season 2015/16 and 2016/17 combined | Pearson correlation | P value |

| High deprivation | ||

| % upper secondary school | 0.992 | 0.049 |

| % not belonging to the labor force | 0.997 | 0.043 |

| % other employment status | -0.998 | 0.041 |

| % earners from labor or capital income | 0.992 | 0.042 |

| % entrepreneurs | 0.996 | 0.049 |

| % self-employed | 0.995 | 0.045 |

| % single-parent families with children under 15 years | -0.992 | 0.042 |

| Medium-high deprivation | ||

| % 3-member families | 0.586 | 0.013 |

| Medium deprivation | ||

| % married | 0.326 | 0.024 |

| Medium-low deprivation | ||

| % primary school diploma | -0.510 | 0.063 |

| % 3-member families | 0.503 | 0.067 |

| % employees | -0.718 | 0.004 |

| Low deprivation | ||

| % 2-member families | 0.450 | 0.031 |

| % 3-member families | -0.422 | 0.045 |

*= p < 0.05

** = p < 0.01.

Discussion

Using census data to quantify socio-economic deprivation is a generally well-accepted method of identifying populations with poorer health outcomes [10]. In particular, since influenza immunization among the elderly is an important public health intervention to prevent unnecessary hospitalizations and premature death, the use of socio-economic deprivation indexes has been proposed in order to identify non-vaccinating subgroups [11].

In recent years, the age structure of the Florentine population has shown a reduction in the central age-groups and a steady increasein the elderly population. In particular, the percentage of older women living alone increases with age, and these subjects constitute a group at high risk of social isolation and poverty [3, 4, 12].

In the present study, a specific deprivation index, the SEHDI, was drawn up and validated at the local level, in order to obtain a better estimation of health inequalities associated with environmental factors.

Regarding validation of the SEHDI, the present study confirmed, as expected, that elderly people are more likely to belong to the most deprived group. With regard to health-related validation, mortality was clustered by both overall and cause-specific mortality in this study. The results showed that increasing deprivation is significantly associated with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. The association with socio-economic deprivation is less clear with regard to mortality due to colorectal cancer, which showed higher values in the medium-low, medium and medium-high deprivation groups. These results are consistent with those of previous studies, which have demonstrated that people living in more deprived areas have higher mortality rates than those living in less deprived areas [13-16].

From the analysis of the distribution of deprivation in the municipality of Florence, it emerges that the most deprived area is the western suburb, where the poorest people live. By contrast, the central area of the city appears to be the least deprived, although it does contain some deprived quarters. This could be due to the fact that not only economic but also familial and social factors (such as living alone, less access to health services) are involved in deprivation.

Vaccination coverage in the two flu-seasons proved to be low and did not meet the goal of 75% uptake among older people, which is the national minimum target set for people over 65y [16]; indeed, VC values were below 65%, which is very far from the optimal national target of 95%.

Application of the SEHDI to elderly people in the municipality of Florence revealed that adherence to influenza vaccination was greatest in the sub-group with the highest level of deprivation. These results differ from some previous findings. Indeed, a systematic review conducted in 2017, which investigated the association between deprivation indexes and anti-influenza vaccination coverage in the elderly population, found that elderly subjects belonging to the least deprived group were significantly more likely to be vaccinated than those in the most deprived group [11]. Moreover, Anu Jain et al. [18] reported that seasonal influenza vaccination uptake was modestly lower (7-11%) amongst those living in the most deprived areas.

On examining the individual Census variables, it is possible to identify some characteristics that further define the sub-groups of population with lower vaccination uptake. The results showed a positive correlation between immunization coverage and the percentage of married people and the average number of family members. By contrast, a negative correlation emerged between vaccination coverage and the percentage of divorced/single/unmarried people (probably living alone) and unemployed people.

Vaccination coverage also appears to be correlated with different factors in the different deprivation groups, confirming that socio-economic status plays an important role in health choices. Thus, the data on vaccination coverage in the municipality of Florence, when integrated with the index of territorial deprivation, allow us to identify specific sub-groups of the older population that do not sufficiently adhere to seasonal influenza vaccination advice.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, mortality data and immunization coverage data refer to different periods; this is due to the unavailability of the most recent mortality data in the period of data collection. Secondly, vaccination coverage was calculated only for the two most recent influenza seasons (2015/16 and 2016/17), since digital data on previous years were not available (data from 2009/10 to 2013/14 were available only on paper). Moreover, influenza vaccination coverage data could be affected by possible bias regarding the correspondence between the address of each GP’s outpatient clinic and the census section of the Municipality of Florence. Indeed, citizens in Tuscany can choose their GP from among all those who work in the area that includes their municipality of residence. Consequently, a resident of Florence may have chosen a GP whose outpatient clinic was on the opposite side of the city, or even in another municipality in the same area. The same applies to residents of other municipalities in the same area, who may have chosen a GP from the municipality of Florence, although they did not reside in this municipality. Moreover, a GP may have several clinics in the same municipality.

Conclusions

In order to increase vaccination uptake and to understand the factors that influence immunization coverage, deprivation indexes can constitute a useful tool to share with the GPs in the territory. The results of the present study should be communicated to GPs, in order to help them to promote influenza vaccination among their patients, particularly those patients who are less likely to be vaccinated and who are at higher risk of death.

Continuing medical education, even in the form of distance learning, could constitute a useful application of the Project.

Tab. I.

Rates of general and cause-specific mortality in each deprivation group.

| A) General and cause-specific mortality rates (respiratory tract diseases) | ||||

| Deprivation group | General mortality SMR(95%CI) |

Respiratory tract SMR(95%CI) |

Pneumonia/Flu SMR (95%CI) |

COPD SMR(95%CI) |

| High deprivation | 1.22(1.17-1.27) | 1.51(1.29-1.74) | 2.06(1.49-2.62) | 1.29(0.99-1.29) |

| Medium-high deprivation | 1.04(1.00-1.07) | 1.08(0.94-1.22) | 1.23(0.90-1.56) | 1.10(0.89-1.30) |

| Medium deprivation | 1.10(1.08-1.12) | 1.25(1.16-1.34) | 1.79(1.56-2.02) | 1.08(0.97-1.20) |

| Medium-low deprivation | 1.13(1.09-1.16) | 1.22(1.06-1.39) | 1.39(1.02-1.77) | 1.04(0.82-1.25) |

| Low deprivation | 1.00(0.96-1.05) | 1.08(0.89-1.26) | 1.36(0.90-1.81) | 1.05(0.78-1.32) |

| Total | 1.09(1.08-1.11) | 1.23(1.17-1.29) | 1.63(1.47-1.78) | 1.10(1.01-1.18) |

| Trend | p<0.05 n.l. | p<0.05 l. | p<0.05 l. | p<0.05 l. |

| B) Cause-specific mortality rates (cancer) | ||||

| Deprivation group |

All cancers SMR(95%CI) |

Stomach SMR(95%CI) |

Colorectal SMR(95%CI) |

Lung SMR(95%CI) |

| High deprivation | 1.20(1.09-1.30) | 1.50(1.06-1.95) | 1.26(0.94-1.58) | 1.77(1.48-2.05) |

| Medium-high deprivation | 1.02(0.95-1.09) | 1.08(0.80-1.37) | 1.30(1.05-1.54) | 1.24(1.06-1.42) |

| Medium deprivation | 1.05(1.01-1.09) | 0.99(0-83-1.14) | 1.40(1.26-1.55) | 1.12(1.02-1.22) |

| Medium-low deprivation | 1.11(1.03-1.19) | 1.19(0-86-1.51) | 1.52(1.23-1.81) | 1.21(1.01-1.40) |

| Low deprivation | 0.88(0.79-0.97) | 0.95(0.60-1.30) | 1.00(0.71-1.28) | 0.89(0.68-1.09) |

| Total | 1.05(1.02-1.08) | 1.08(0.96-1.19) | 1.35(1.25-1.45) | 1.19(1.12-1.26) |

| Trend | p<0.05 n.l. | p<0.05 l. | p<0.05 l. | p<0.05 l. |

| C) Breast cancer and prostate cancer mortality rates | ||||

| Deprivation group |

Breast cancer (F) SMR(95%CI) |

Prostate cancer (M) SMR(95%CI) |

||

| High deprivation | 1.35(0.93-1./8) | 1.36(0.83-1.98) | ||

| Medium-high deprivation | 1.04(0-75-1.33) | 1.03(0-68-1.38) | ||

| Medium deprivation | 1.13(0.96-1.29) | 1.03(0.83-1.22) | ||

| Medium-low deprivation | 1.27(0.93-1.61) | 0.92(0.57-1.28) | ||

| Low deprivation | 1.14(0.72-1.55) | 0.68(0.30-1.07) | ||

| Total | 1.16(1.03-1.28) | 1.01(0.87-1.15) | ||

| Trend | p<0.05 n.l. | p<0.05 l. | ||

n.l.: non-linear trend; l.: linear trend; F = females; M = males.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the General Practitioners of the Municipality of Florence.

The current research was funded by the Ministry of Health (CCM 2015 Program).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

AB and FP made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, and/or to data acquisition (FP, PF, EB, AM, LB), analysis and interpretation (AB, FP, GD, FC, TS). SB and PB participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors give their final approval of the version to be submitted and any revised version.

References

- [1].Demo-ISTAT. Available at: http://demo.istat.it. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [2].Censimento 2011 Firenze. Available at: www.tuttitalia.it/toscana/77-firenze/statistiche/censimento-2011. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [3].Popolazione per età, sesso e stato civile 2018. Available at: www.tuttitalia.it/toscana/77-firenze/statistiche/popolazione-eta-sesso-stato-civile-2018. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [4].Indici demografici e Struttura di Firenze. Available at: www.tuttitalia.it/toscana/77-firenze/statistiche/indici-demografici-struttura-popolazione. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [5].Osservatorio della SdS di Firenze. Profilo di salute e dei servizi socio-sanitari. Relazione sullo stato di salute di Firenze. Anno 2012, Edizione 2014 Available at: www.sds.firenze.it/export/sites/default/materiali/Assemblea_Soci_Giunta_Esecutiva_2014/alldel5_14AS.pdf. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [6].Banca dati mARSupio. Available at: www.ars.toscana.it/portale-dati-marsupio-dettaglio.html?codice_asl=9000. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [7].ISTAT. Available at: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=20745. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [8].Comune di Firenze, Osservatorio Sociale e Sistema Informativo, Ufficio Comunale di Statistica. Profilo di salute della Società della Salute di Firenze. Aggiornamento dati 2016. Available at: www.sds.firenze.it/materiali/Atti_2017/allAdel8_17AS.pdf. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [9].Lillini R, Quaglia A, Vercelli M, Registro mortalità Regione Liguria Building of a local deprivation index to measure the health status in the Liguria Region. Epidemiol Prev 2012;36:180-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schuurman N, Bell N, Dunn JR, Oliver L. Deprivation indices, population health and geography: an evaluation of the spatial effectiveness of indices at multiple scales. J Urban Health 2007;84:591-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vukovic V, Gasparini R, Amicizia D, Arata L, Boccalini S, Fortunato F, Lillini R, Panatto D, Stefanati A, de Waure C. Identifying elderly with low vaccine uptake using social deprivation indices: a systematic review. Eur J Publ Health 2017;27(Suppl 3). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Elderly women living alone: an update of their living conditions. European Parliament, 2015. www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/519219/IPOL_STU%282015%29519219_EN.pdf. [Accessed 5 November 2018].

- [13].Aungkulanon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Shibuya K, Bundhamcharoen K, Chongsuvivatwong V. Area-level socioeconomic deprivation and mortality differentials in Thailand: results from principal component analysis and cluster analysis. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:117 10.1186/s12939-017-0613-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hoffmann R, Borsboom G, Saez M, Mari Dell’Olmo M, Burstrom B, Corman D, Costa C, Deboosere P, Domínguez-Berjón MF, Dzúrová D, Gandarillas A, Gotsens M, Kovács K, Mackenbach J, Martikainen P, Maynou L, Morrison J, Palència L, Pérez G, Pikhart H, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Santana P, Saurina C, Tarkiainen L, Borrell C. Social differences in avoidable mortality between small areas of 15 European cities: an ecological study. Int J Health Geogr 2014;13:8 doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Higher mortality in areas of lower socioeconomic position measured by a single index of deprivation in Japan. Public Health 2007;121:163-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cadum E, Costa G, Biggeri A, Martuzzi M. Deprivation and mortality: a deprivation index suitable for geographical analysis of inequalities. Epidemiol Prev 1999;23:175-87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ministero della Salute. Prevenzione e controllo dell’influenza: raccomandazioni per la stagione 2018-2019. Available at: www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2018&codLeg=64381&parte=1%20&serie=null. [Accessed on 5 November 2018].

- [18].Jain A, van Hoek AJ, Boccia D, Thomas SL. Lower vaccine uptake amongst older individuals living alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis of social determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine 2017;25;35:2315-28. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]