Abstract

Background

Age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of uncorrectable severe vision loss in people aged 55 years and older in the developed world. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to AMD accounts for most cases of AMD‐related severe vision loss. Intravitreous injection of anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) agents aims to block the growth of abnormal blood vessels in the eye to prevent vision loss and, in some instances, to improve vision.

Objectives

• To investigate ocular and systemic effects of, and quality of life associated with, intravitreous injection of three anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab) versus no anti‐VEGF treatment for patients with neovascular AMD

• To compare the relative effects of one of these anti‐VEGF agents versus another when administered in comparable dosages and regimens

Search methods

To identify eligible studies for this review, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register (searched January 31, 2018); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to January 31, 2018); Embase Ovid (1947 to January 31, 2018); the Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (1982 to January 31, 2018); the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) Registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch ‐ searched January 31, 2018); ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov ‐ searched November 28, 2018); and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en ‐ searched January 31, 2018). We did not impose any date or language restrictions in electronic searches for trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated pegaptanib, ranibizumab, or bevacizumab versus each other or versus a control treatment (e.g. sham treatment, photodynamic therapy), in which participants were followed for at least one year.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened records, extracted data, and assessed risks of bias. We contacted trial authors for additional data. We compared outcomes using risk ratios (RRs) or mean differences (MDs). We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 16 RCTs that had enrolled a total of 6347 participants with neovascular AMD (the number of participants per trial ranged from 23 to 1208) and identified one potentially relevant ongoing trial. Six trials compared anti‐VEGF treatment (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, or bevacizumab) versus control, and 10 trials compared bevacizumab versus ranibizumab. Pharmaceutical companies conducted or sponsored four trials but funded none of the studies that evaluated bevacizumab. Researchers conducted these trials at various centers across five continents (North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia). The overall certainty of the evidence was moderate to high, and most trials had an overall low risk of bias. All but one trial had been registered prospectively.

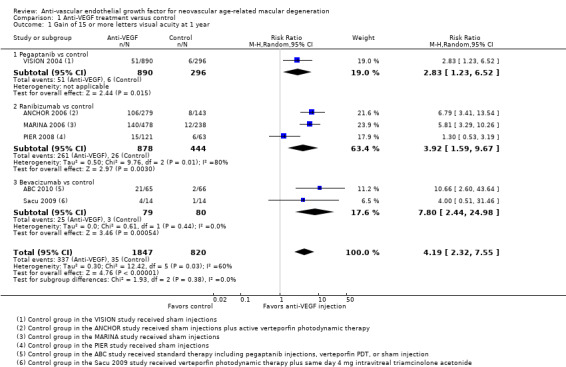

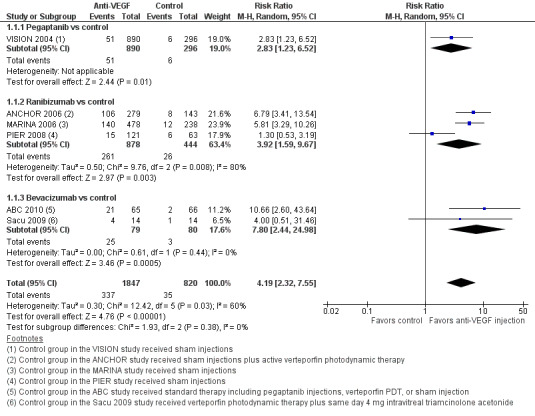

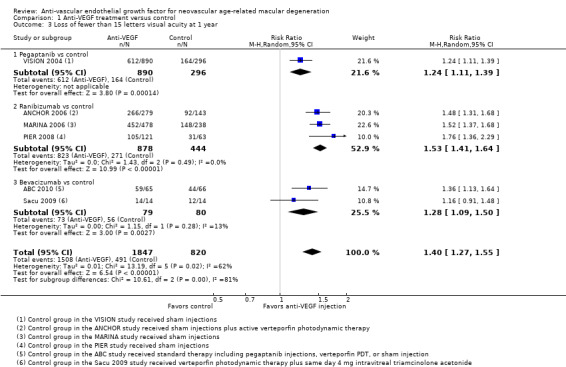

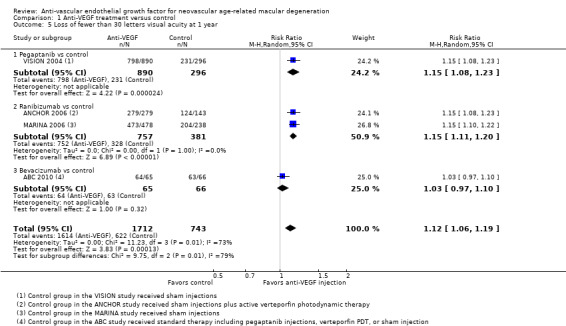

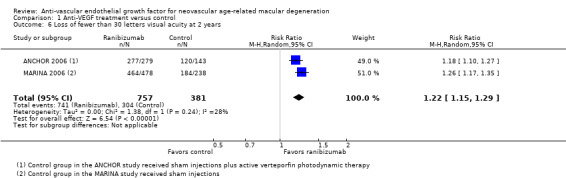

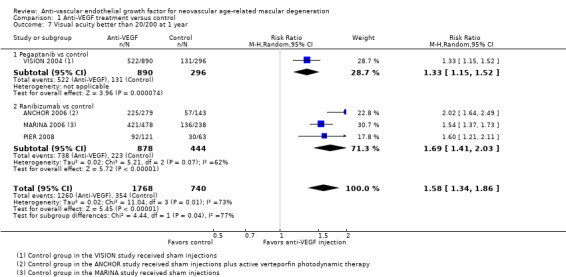

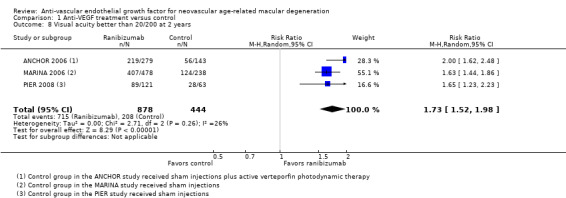

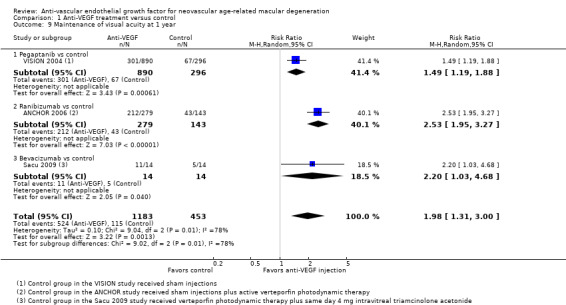

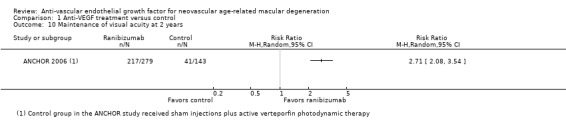

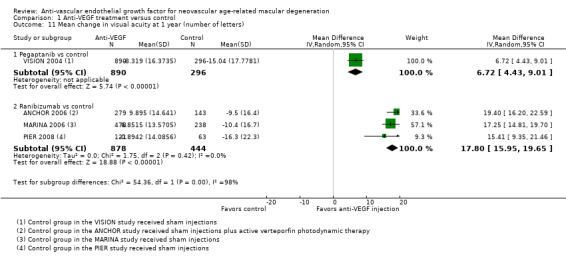

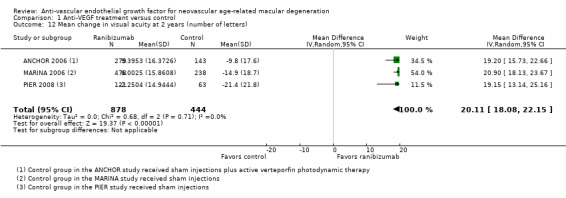

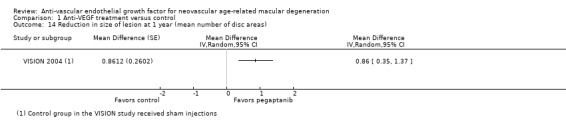

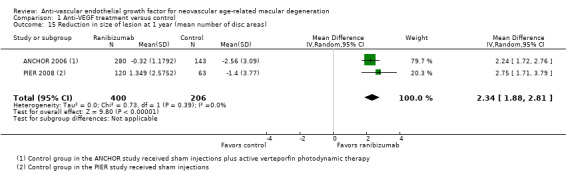

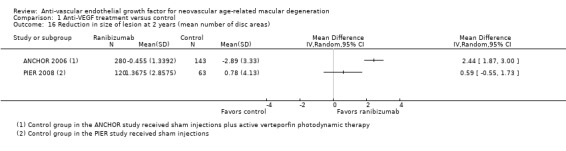

When compared with those who received control treatment, more participants who received intravitreous injection of any of the three anti‐VEGF agents had gained 15 letters or more of visual acuity (risk ratio [RR] 4.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.32 to 7.55; moderate‐certainty evidence), had lost fewer than 15 letters of visual acuity (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.55; high‐certainty evidence), and showed mean improvement in visual acuity (mean difference 6.7 letters, 95% CI 4.4 to 9.0 in one pegaptanib trial; mean difference 17.8 letters, 95% CI 16.0 to 19.7 in three ranibizumab trials; moderate‐certainty evidence) after one year of follow‐up. Participants treated with anti‐VEGF agents showed improvement in morphologic outcomes (e.g. size of CNV, central retinal thickness) compared with participants not treated with anti‐VEGF agents (moderate‐certainty evidence). No trial directly compared pegaptanib versus another anti‐VEGF agent and followed participants for one year; however, when compared with control treatments, ranibizumab and bevacizumab each yielded larger improvements in visual acuity outcomes than pegaptanib.

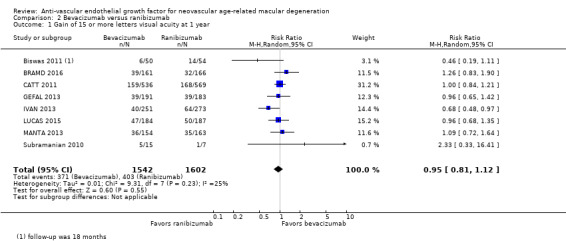

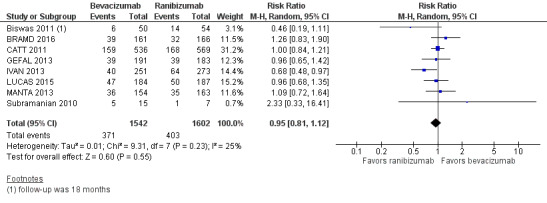

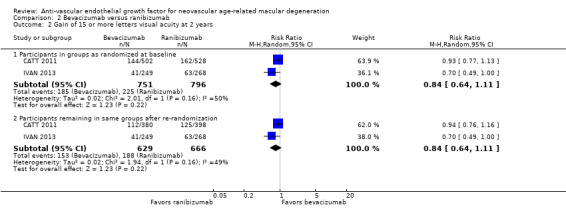

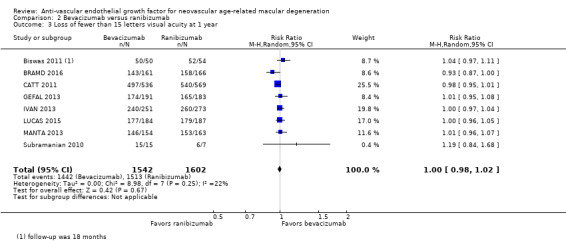

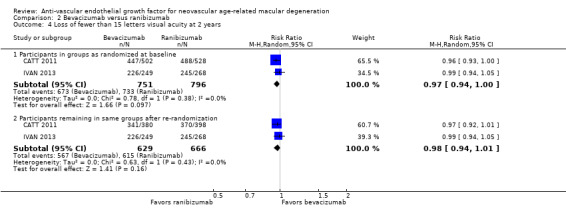

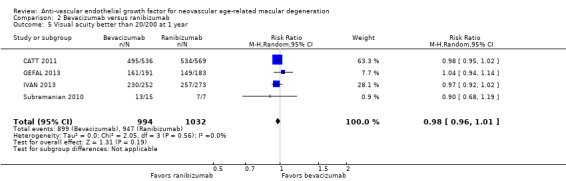

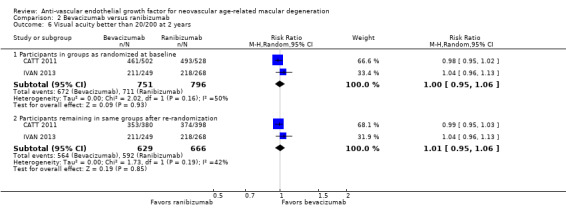

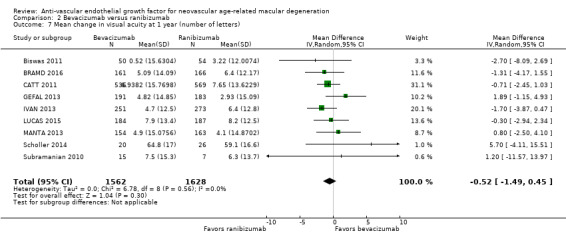

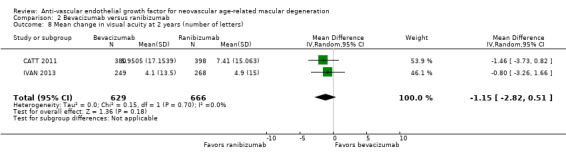

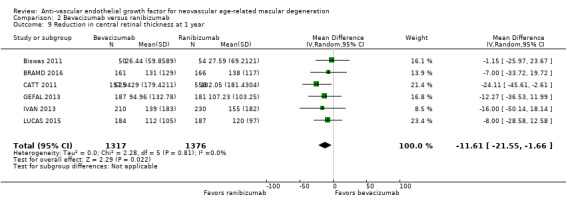

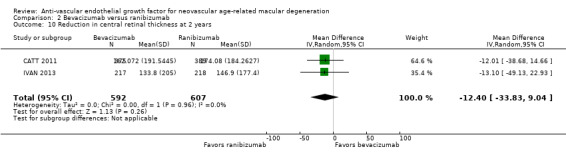

Visual acuity outcomes after bevacizumab and ranibizumab were similar when the same RCTs compared the same regimens with respect to gain of 15 or more letters of visual acuity (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.12; high‐certainty evidence) and loss of fewer than 15 letters of visual acuity (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.02; high‐certainty evidence); results showed similar mean improvement in visual acuity (mean difference [MD] ‐0.5 letters, 95% CI ‐1.5 to 0.5; high‐certainty evidence) after one year of follow‐up, despite the substantially lower cost of bevacizumab compared with ranibizumab. Reduction in central retinal thickness was less among bevacizumab‐treated participants than among ranibizumab‐treated participants after one year (MD ‐11.6 μm, 95% CI ‐21.6 to ‐1.7; high‐certainty evidence); however, this difference is within the range of measurement error, and we did not interpret it to be clinically meaningful.

Ocular inflammation and increased intraocular pressure (IOP) after intravitreal injection were the most frequently reported serious ocular adverse events. Researchers reported endophthalmitis in less than 1% of anti‐VEGF‐treated participants and in no cases among control groups. The occurrence of serious systemic adverse events was comparable across anti‐VEGF‐treated groups and control groups; however, the numbers of events and trial participants may have been insufficient to show a meaningful difference between groups (evidence of low‐ to moderate‐certainty). Investigators rarely measured and reported data on visual function, quality of life, or economic outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Results of this review show the effectiveness of anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab) in terms of maintaining visual acuity; studies show that ranibizumab and bevacizumab improved visual acuity in some eyes that received these agents and were equally effective. Available information on the adverse effects of each medication does not suggest a higher incidence of potentially vision‐threatening complications with intravitreous injection of anti‐VEGF agents compared with control interventions; however, clinical trial sample sizes were not sufficient to estimate differences in rare safety outcomes. Future Cochrane Reviews should incorporate research evaluating variable dosing regimens of anti‐VEGF agents, effects of long‐term use, use of combination therapies (e.g. anti‐VEGF treatment plus photodynamic therapy), and other methods of delivering these agents.

Plain language summary

Anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular age‐related macular degeneration

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane review was to compare treatment with anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (anti‐VEGF) agents for neovascular age‐related macular degeneration (wet AMD). This review focuses on two questions: (1) whether using anti‐VEGF agents is better than not using them, and (2) which anti‐VEGF agent works best.

Key messages Anti‐VEGF agents were better than no anti‐VEGF agents or other types of treatment for patients with wet AMD. When studies compared anti‐VEGF agents, researchers found that ranibizumab and bevacizumab were similar in terms of vision‐related outcomes and numbers of adverse events among participants followed for at least one year. The major difference was cost, as bevacizumab was cheaper.

What was studied in this review? Wet AMD is a common cause of severe vision loss among people 55 years of age and older. The macula, located in the central retina in the back of the eye, is important for vision. Wet AMD occurs when abnormal growth of blood vessels in the back of the eye damages the macula. Wet AMD causes blurriness, darkness, or distortion in the center of the field of vision, thus reducing the individual's ability to read, drive, and see faces.

Injection into the eye of medicines like pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab can help block abnormal growth of blood vessels in the back of the eye. These drugs are known as anti‐VEGF agents. We conducted this review to compare benefits and risks of treatment with anti‐VEGF agents versus treatment without anti‐VEGF agents and to compare different types of anti‐VEGF agents.

What are the main results of the review? We found 16 studies that enrolled a total of 6347 people with wet AMD. Six studies compared anti‐VEGF agents against no anti‐VEGF agent, and ten studies compared bevacizumab versus ranibizumab. Drug companies conducted or sponsored four of the studies. Investigators conducted the 16 studies at various centers on five continents (North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia); they treated people and provided follow‐up for at least one year.

After one year, more people treated with any of the three anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, or bevacizumab) had improved vision, fewer had vision loss, and fewer were legally blind in the study eye when compared with people who did not receive anti‐VEGF agents. People treated with anti‐VEGF agents also showed structural improvements in the eye, which doctors use to monitor the disease and determine the need for more treatment. People who did not receive anti‐VEGF agents did not show the same kind of improvement.

Treatment with ranibizumab or bevacizumab yielded larger improvements in vision compared with treatment with pegaptanib in trials comparing anti‐VEGF treatment against treatment not using anti‐VEGF agents. Comparison of bevacizumab versus ranibizumab revealed no major differences with respect to any vision‐related outcomes. The major difference between the two agents was cost; bevacizumab was cheaper.

Inflammation and increased pressure in the eye were the most common unwanted effects caused by anti‐VEGF agents. Investigators reported endophthalmitis (infection in the inner part of the eye, which can cause blindness) in less than 1% of anti‐VEGF‐treated eyes and observed no cases among those not treated with anti‐VEGF agents. The occurrence of serious side effects, such as high blood pressure and internal bleeding, was low and was similar between anti‐VEGF‐treated groups and groups that did not receive anti‐VEGFs. The number of total side effects was very small, so it is impossible to tell which drug may have caused the most harmful effects.

How up‐to‐date is this review? Cochrane researchers searched for studies that had been published up to January 31, 2018.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Introduction

Age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive, degenerative disease of the retina that occurs with increasing frequency with advancing age. Two major types of AMD are known; these are commonly referred to as non‐neovascular ("dry") and neovascular ("wet") AMD. The non‐neovascular type is characterized by drusen (yellow spots under the retina), pigmentary changes (redistribution of melanin within the retinal pigment epithelium [RPE] under the retina and migration of melanin into the retina), and geographic atrophy (loss of the RPE and choriocapillaris).

This review is concerned with neovascular AMD and its treatment. The hallmark of neovascular AMD is choroidal neovascularization (CNV). Breaks in the RPE and in Bruch’s membrane allow naturally occurring vessels in the choroid to grow aberrantly into the subretinal space. These choroidal neovascular vessels typically leak and bleed, causing exudative or hemorrhagic retinal detachments. Without treatment, the process usually evolves into a fibrous scar, which replaces the outer layers of the retina, the RPE, and the choriocapillaris. The scarred retina has greatly diminished visual capacity.

Epidemiology

AMD is a leading cause of irreversible vision loss among the elderly in developed countries (Bourne 2014; Bunce 2006; Congdon 2004; Ghafour 1983; Hyman 1987; Leibowitz 1980; Tielsch 1994). Although the non‐neovascular type is much more common, the neovascular form of AMD is responsible for most cases of severe vision loss. The incidence of progression from non‐neovascular AMD to neovascular AMD is increased by the presence of numerous large and confluent drusen in the macula, as well as by the presence of pigment in the macula. Neovascular AMD occurs in only 10% of people with AMD, yet 80% of those with severe visual loss (worse than 20/200 Snellen acuity) have the neovascular form (Leibowitz 1980). Once neovascular disease develops in one eye, the risk of developing neovascular disease in the other eye of the same person is approximately 40% by five years (AREDS 2001; SST 20).

The overall prevalence of AMD, estimated in a meta‐analysis of studies from Australia, Europe, and the United States, was 1.47% (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.38% to 1.55%) (Friedman 2004); however, AMD increases in prevalence with advancing age, and incidence is low among individuals younger than 50 years of age. Thus, the burden of disease is greatest in regions where life expectancy is highest. Among those aged 80 years or older, the prevalence of neovascular AMD has been estimated to be 5.79% (95% CI 4.72% to 7.01%) in the UK (Owen 2003), and 8.18% (95% CI 7.07% to 9.29%) in the United States (Friedman 2004).

No consistent evidence indicates that modifiable factors such as lipid levels, blood pressure, light exposure, or alcohol intake put people at greater risk of AMD. One notable exception is smoking (Klein 2008; Mitchell 2002; Smith 1996). Elevated baseline levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C‐reactive protein have been found to be associated with the development of early and late AMD in a large population‐based cohort (Boekhoorn 2007). Furthermore, several studies have shown gene‐environment interactions of complement factor H with smoking and C‐reactive protein (Deangelis 2007; Haddad 2006; Schaumberg 2007; Seddon 2006). High doses of vitamins C and E, beta‐carotene, and zinc provide a modest protective effect against progression to advanced AMD among individuals with extensive drusen or in initially unaffected fellow eyes with neovascular AMD (AREDS 2001; AREDS2 2013).

As the population continues to age, a higher prevalence of this disease is expected in the future, at least in certain populations. A population‐based survey estimated that AMD, as a contributing cause of blindness, had increased worldwide from 4.4% (95% CI 4.0 to 5.1) in 1990 to 6.6% (95% CI 5.9 to 7.9) in 2010 (Bourne 2014).

Presentation and diagnosis

Neovascular AMD may affect one eye or both eyes at the same time or sequentially. Symptoms of neovascular AMD include metamorphopsia (distortions while looking at objects), scotomata (black or gray spots), and blurry vision. Depending upon the location of the CNV and the quality of vision in the fellow eye, individuals with AMD may be unaware of a change in visual acuity or may note difficulty when performing normal activities that require good central vision, such as reading and writing, watching television, driving, and recognizing faces. When AMD affects only one eye, visual loss may go undetected until monocular testing is performed at a routine eye examination, or until chance occlusion of the better eye is noted. Frequently, people are unaware that their disturbed binocular vision is caused by changes in only one eye.

Neovascular AMD is diagnosed clinically with the help of imaging such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography, which may be necessary to detect subtle exudation in some individuals who have experienced a recent change in visual acuity. At the onset of symptoms, fundus examination often reveals subretinal exudation of fluid, lipid, or blood. OCT, a non‐invasive imaging modality, shows cross‐sectional images of the retina, RPE, and choroid. Some studies have defined the characteristic appearance of different stages of the disease process on OCT (Ting 2002; Van Kerckhoven 2001). The most characteristic findings on OCT corresponding to a CNV lesion include areas of hyporeflectivity under the retina that, in turn, correspond to subretinal fluid, cystic hyporeflective changes consistent with macular edema, and attenuation of the photoreceptor/choriocapillaris layer. CNV can be seen in several characteristic patterns on fluorescein angiography. Classic CNV is defined as an area of early hyperfluorescence with increasing fluorescein leakage on late frames of the angiogram (MPSG 1991). Occult CNV occurs in two different patterns: fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment and late fluorescein leakage from an undetermined source. Classic CNV typically has well‐demarcated borders, in contrast to the poorly demarcated borders usually seen in occult CNV.

Another test ‐ indocyanine green (ICG) angiography ‐ may facilitate evaluation of individuals with neovascular AMD, as it images the choroidal circulation better than fluorescein angiography and may show "hot" spots under the RPE that are amenable to treatment. ICG angiography is particularly useful in the diagnosis of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, a form of AMD that is most common among Asian populations.

Description of the intervention

Until the advent of anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents, treatments most frequently used for neovascular AMD included thermal laser photocoagulation and verteporfin photodynamic therapy (PDT). A Cochrane systematic review concluded that laser photocoagulation effectively slowed the progression of neovascularization in non‐subfoveal lesions compared with observation alone (Virgili 2007). A Cochrane review of verteporfin PDT concluded that PDT was effective in preventing clinically significant vision loss (Wormald 2007). However, neither laser photocoagulation nor PDT offered any significant chance for vision improvement.

Over the past two decades, researchers have developed new drugs for the treatment of patients with neovascular AMD. These drugs target a protein in the body known as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates the growth of abnormal blood vessels in neovascular AMD through a process called angiogenesis; the drugs block VEGF, leading to regression of abnormal blood vessels. Antiangiogenic therapy currently is the most commonly used treatment for neovascular AMD, particularly of subfoveal neovascular lesions.

An example of an anti‐VEGF antagonist is pegaptanib (Macugen, a trademark of Eyetech/Pfizer, Inc.). Pegaptanib is a chemically synthesized 28‐base ribonucleic acid molecule. It is an aptamer (foldable single‐strand nucleic acid) that has the ability to change its three‐dimensional structure to fit a target protein, in this case VEGF. By binding to VEGF, pegaptanib blocks and inactivates VEGF, thus halting the process of neovascularization. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pegaptanib in December 2004 for the treatment of patients with neovascular AMD.

Ranibizumab, previously known as rhuFab‐VEGF (Lucentis, a trademark of Genentech, Inc.), is another example of an anti‐VEGF medication developed for ocular administration. It is a humanised antibody fragment capable of binding to the VEGF protein to prevent it from binding to its receptor, thus inhibiting angiogenic activity. Ranibizumab was the first treatment for neovascular AMD that offered a realistic hope for vision improvement; it was approved by the FDA in 2007.

Bevacizumab (Avastin, a trademark of Genentech, Inc.) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF. It is the larger parent molecule from which ranibizumab was derived. Bevacizumab currently is approved for the treatment of patients with conditions such as colorectal cancer, but it is widely used off‐label by ophthalmologists to treat neovascular AMD.

Aflibercept, previously known as VEGF Trap (Eylea, a trademark of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), is another anti‐VEGF agent; the molecule serves as a VEGF decoy to inhibit the growth of new blood vessels. The FDA approved aflibercept in 2011 for treatment of neovascular AMD. Conbercept, a drug similar to aflibercept, has been developed in China. Because the mechanism of action of these types of drugs is slightly different from that of the drugs listed above (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab), and because they were introduced after the protocol for this review was developed, we have not evaluated aflibercept or conbercept in this review.

How the intervention might work

Angiogenesis is a complex process whereby interactions between stimulatory and inhibitory factors result in new blood vessel formation. These factors have been identified in CNV formation in animal models and human tissue (Aiello 1994; Kvanta 1996; Lopez 1996). Antiangiogenic therapies work by blocking stimulatory factors or by promoting inhibitory factors, thus disrupting the formation of new vessels. Agents that block the activity of VEGF (anti‐VEGFs), a polypeptide with mitogenic effects on endothelial blood vessels, form one type of anti‐angiogenic therapy. VEGF antagonists have been shown to inhibit CNV in animal models.

In the past, the primary goal of both laser photocoagulation and PDT was to prevent or delay further loss of visual acuity in the treated eye. With the development of agents to counteract VEGF, together known as anti‐VEGF agents, the primary goal of intravitreal injection of these agents is to retain or improve visual acuity. Currently, anti‐VEGF agents are administered most commonly via monthly intravitreous injections or as needed after three consecutive monthly injections.

Why it is important to do this review

Previous versions of this Cochrane review have documented the effectiveness of anti‐VEGF agents in halting the loss of visual acuity in a substantial fraction of treated eyes (Solomon 2014; Vedula 2008). Further, intravitreal injections with ranibizumab led to improved vision in about one‐third of eyes ‐ an improvement not previously observed with other AMD treatments (Solomon 2014; Solomon 2016). Since this Cochrane review was first published in 2008, numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of various anti‐VEGF agents, treatment regimens, and combination therapies for treatment of patients with neovascular AMD (Table 3). This review is restricted to primary randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of anti‐VEGF agents versus no anti‐VEGF treatment; and head‐to‐head (comparative effectiveness) RCTs of one anti‐VEGF agent versus another. Studies on dosage, different treatment strategies, and anti‐VEGF agents combined with other treatments are outside the scope of this review. The emphasis of this updated review is improvement in visual acuity with treatment.

1. Table of study acronyms.

| Acronym | Details |

| Included studies | |

| ABC | The Avastin® (Bevacizumab) in Choroidal Neovascularization Trial |

| ANCHOR | Anti‐VEGF Antibody for the Treatment of Predominantly Classic Choroidal Neovascularization in Age‐related Macular Degeneration |

| BRAMD | Comparison of Bevacizumab (Avastin®) and Ranibizumab (Lucentis®) in Exudative Age‐related Macular Degeneration |

| CATT | Comparison of Age‐related Macular Degeneration Treatment Trials |

| GEFAL | French Evaluation Group Avastin® Versus Lucentis® |

| IVAN | A Randomized Controlled Trial of Alternative Treatments to Inhibit VEGF in Age‐related Choroidal Neovascularisation |

| LUCAS | Lucentis® Compared to Avastin® Study |

| MANTA | A Randomized Observer and Subject Masked Trial Comparing the Visual Outcome After Treatment With Ranibizumab or Bevacizumab in Patients With Neovascular Age‐related Macular Degeneration Multicenter Anti‐VEGF Trial in Austria |

| MARINA | Minimally Classic/Occult Trial of the Anti‐VEGF Antibody Ranibizumab in the Treatment of Neovascular Age‐Related Macular Degeneration |

| PIER | A Phase IIIb, Multicenter, Randomized, Double‐Masked, Sham Injection‐Controlled Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Ranibizumab in Subjects With Subfoveal Choroidal Neovascularization With or Without Classic CNV Secondary to Age‐related Macular Degeneration |

| SAVE‐AMD | Safety of VEGF Inhibitors in Age‐Related Macular Degeneration |

| VISION | VEGF Inhibition Study in Ocular Neovascularization |

| Ongoing study | |

| VIBERA | Prevention of Vision Loss in Patients With Age‐Related Macular Degeneration by Intravitreal Injection of Bevacizumab and Ranibizumab |

Objectives

To investigate ocular and systemic effects of, and quality of life associated with, intravitreous injection of anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab) versus no anti‐VEGF treatment for patients with neovascular AMD

To compare the relative effects of one of these anti‐VEGF agents versus another when administered in comparable dosages and regimens

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only RCTs in this review.

Types of participants

We included trials in which participants had neovascular AMD as defined by study investigators.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared anti‐VEGF treatment versus another treatment, sham treatment, or no treatment. We did not include studies that compared different doses of one anti‐VEGF treatment against another, studies that included no control or comparator group, or studies that used anti‐VEGF agents in combination with other treatments. We did not include studies of aflibercept (VEGF Trap‐Eye/EYLEA solution) or studies that compared different treatment schedules (e.g. monthly vs as needed dosing), because other Cochrane reviews have evaluated these interventions (Li 2016; Sarwar 2016).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome for this review was based on best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at one‐year follow‐up. All included RCTs randomized only one eye per participant (i.e. the study eye); therefore we defined the primary outcome for the comparison of treatments as the proportion of participants who gained 15 or more letters (three lines) of BCVA in the study eye when BCVA was measured on a visual acuity chart with a LogMAR scale.

Secondary outcomes

Visual acuity outcomes

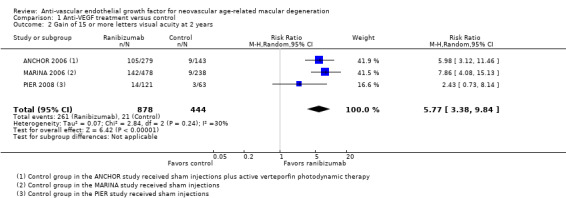

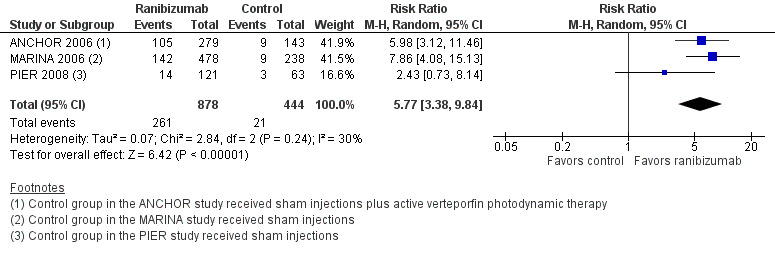

Proportion of participants who gained 15 or more letters of BCVA in the study eye as measured at two‐year follow‐up

Proportion of participants who lost fewer than 15 letters of visual acuity at one year and at two years

Proportion of participants who lost fewer than 30 letters of visual acuity at one year and at two years

Proportion of participants for whom blindness was avoided in the study eye, defined as eyes with visual acuity better than 20/200 at one year and at two years

Proportion of participants maintaining visual acuity, defined as a gain of zero or more letters (i.e. no loss of BCVA from baseline) at one year and at two years

Mean change in visual acuity from baseline to one year and to two years

Other secondary outcomes

Contrast sensitivity, reading speed, or any other validated measure of visual function as measured in the included studies

Assessment of morphologic characteristics by fluorescein angiography or OCT, including mean change in size of CNV, mean change in size of total lesion, and mean change in central retinal thickness (CRT)

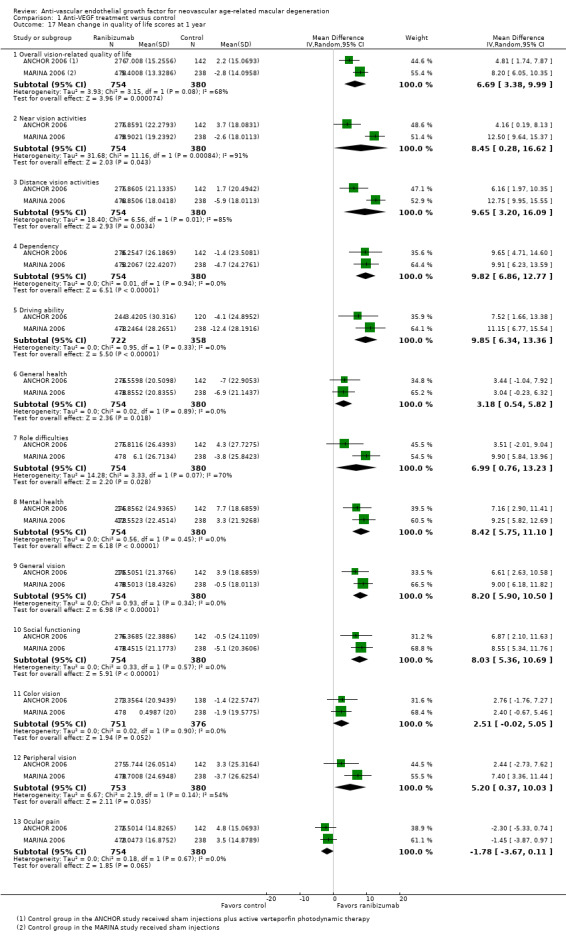

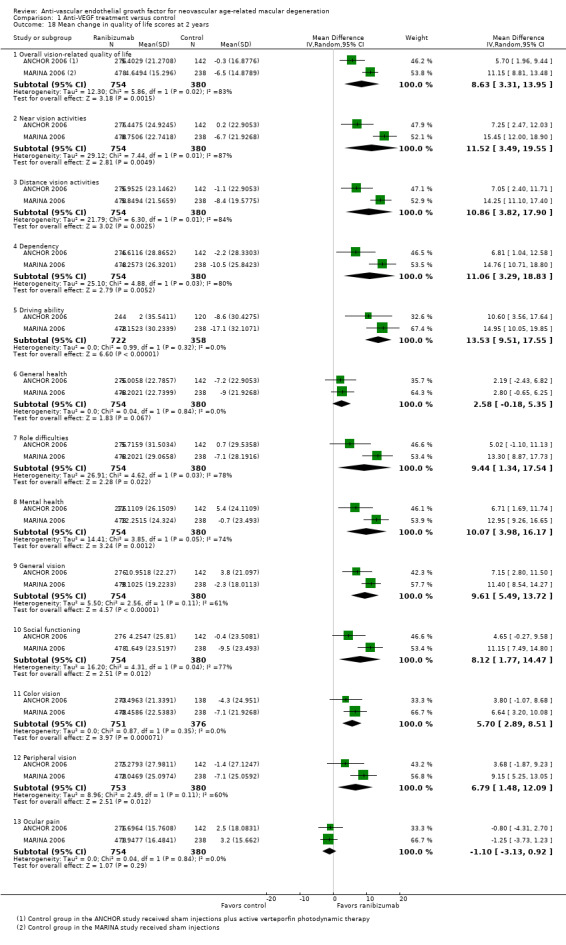

Quality of life measures, as assessed with any validated measurement scale

Economic data, such as comparative cost analyses

Ocular or systemic adverse outcomes

Follow‐up

We included only trials in which participants were followed for at least one year. We also included outcomes at two‐year follow‐up when these data were available.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. This search included no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the most recent search was January 31, 2018.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched January 31, 2018) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to January 31, 2018) (Appendix 2).

Embase Ovid (1980 to January 31, 2018) (Appendix 3).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) information database (1982 to January 31, 2018) (Appendix 4).

International Standard Randomized Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched January 31, 2018) (Appendix 5).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched January 31, 2018) (Appendix 6).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp; searched January 31, 2018) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We reviewed the reference lists of included trial reports and related systematic reviews to identify additional potentially relevant trials.

We contacted pharmaceutical companies conducting or sponsoring studies of anti‐VEGF drugs to ask for information about any ongoing or completed clinical trials not published. One review author (SSV) handsearched abstracts from annual meetings of the Association for Research in Vision & Ophthalmology (ARVO) for the years 2006 and 2007 for ongoing trials (http://files.abstractsonline.com/SUPT/163/1807/PresentationTitle.htm; http://files.abstractsonline.com/SUPT/163/1601/Presentation_Title_PDF_wlinks.htm; accessed November 24, 2007). After 2007, Cochrane Eyes and Vision personnel handsearched conference abstracts reporting clinical trials; the trial records identified are included in CENTRAL. Another review author (KL) handsearched abstracts from the 2006 annual meeting of the European VitreoRetinal Society (http://www.evrs.eu/2006‐evrs‐congress‐cannes/; accessed November 27, 2012). If future updates of this review are performed, we will consider handsearching abstracts for the following conferences when they have not been searched by Cochrane Eyes and Vision: ARVO; Macula Society; Retina Society; subspecialty meetings at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting; American Society of Retinal Surgeons; and European VitreoRetinal Society.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently evaluated the titles and abstracts obtained through electronic searches. We classified each record as "definitely relevant," "possibly relevant," or "definitely not relevant"; a third review author resolved discrepancies. We obtained full‐text reports for all records assessed as "definitely relevant" or "possibly relevant." Two review authors independently assessed the full‐text reports and classified each study as "include," "exclude," "awaiting classification," or "ongoing"; a third review author resolved discrepancies. For trials identified by handsearching of conference abstracts, a second review author verified eligibility based on the stated criteria. We contacted study authors to clarify any details necessary for a complete assessment of relevance of the study. We documented studies excluded after review of the full‐text report and noted the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted study characteristics, including details of study methods, participants, interventions, outcomes, and funding sources, using data collection forms developed specifically for this purpose. We contacted trial authors for data on primary and secondary outcomes of individual trials when this information was not clearly available from published reports. We extracted data regarding visual acuity, adverse events, and other outcomes for the two trials forming part of the VISION 2004 study from documents available on the FDA website. We also extracted data from figures published in trial reports and communicated with study authors to verify extracted data. One review author entered data into Review Manager (Review Manager 5 2014), and a second review author verified the data entered.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors assessed potential sources of bias in trials according to methods set out in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered the following parameters: random sequence generation and method of allocation concealment before randomization (selection bias), masking of participants and researchers (performance bias), masking of outcome assessors (detection bias), rates of loss to follow‐up and non‐compliance as well as failure to include in analyses all randomized participants (attrition bias), reporting bias, and other potential sources of bias. We judged each potential source of bias as conferring low risk, unclear risk, or high risk of bias in each trial and contacted authors of trial reports for additional information when study methods needed to assess bias domains were described unclearly or were not reported.

Measures of treatment effect

Data analysis was guided by Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). The primary outcome and many secondary outcomes for this review relied on measurements of best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of the study eye. We analyzed BCVA, measured on LogMAR charts, as both dichotomous and continuous outcomes. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes. Dichotomous visual acuity outcomes included proportion of participants who gained 15 or more letters (same as a gain of three or more lines) of visual acuity; proportion of participants who lost fewer than 15 letters (fewer than three lines) of visual acuity; proportion of participants who lost fewer than 30 letters (fewer than six lines) of visual acuity; proportion of participants not blind in the study eye (defined as visual acuity better than 20/200); and proportion of participants who maintained baseline visual acuity (gain of zero or more letters) in the study eye. We calculated the mean difference (MD) between treatment groups for mean change in BCVA from baseline to follow‐up time as a continuous visual acuity outcome.

Secondary outcomes related to visual function and morphology of CNV also included both dichotomous and continuous outcomes. We calculated risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes, and mean differences with 95% confidence intervals for continuous outcomes. We reported contrast sensitivity outcomes, measured by Pelli‐Robson charts, both dichotomously (proportion of participants with a gain of nine or more letters, three levels of contrast, on the chart) and continuously (mean number of letters read correctly on the chart) depending on available data. We calculated mean differences with 95% confidence intervals for near visual acuity and reading speed outcomes when sufficient data were available.

Continuous morphologic outcomes included mean change in size of CNV, mean change in total size of the neovascular lesion, and mean change in CRT. We sought data for only one dichotomous morphologic outcome: resolution of subretinal or intraretinal fluid based on OCT evaluation.

We analyzed quality of life scores as continuous data. Because trials that reported quality of life outcomes included in meta‐analyses used the same scale, we did not calculate standardized mean differences.

We reported adverse events as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals when sufficient data were available. Otherwise, we reported the numbers of participants who experienced adverse events in both narrative and tabular form.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual (one study eye per participant).

Dealing with missing data

We used multiple sources to identify relevant data for this review, such as journal publications, conference abstracts, FDA documents, and clinical trial registries. When data were unclear (e.g. numbers were extracted from graphs or were derived from percentages), we contacted study investigators for verification. When data were missing, we contacted study investigators for additional information. If we received no response within two weeks, we attempted to contact them again. When we received no response by six weeks after the first attempt, we used data as available.

For outcome data, we used data provided in trial reports or supplied by primary investigators. We noted the number of participants with missing data and statistical methods used in individual studies to analyze data (e.g. available case analysis, last observation carried forward). We did not impute missing outcome data for our analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity based on the Chi² test, the I² statistic, and the overlap of confidence intervals in forest plots. We considered a Chi² P value < 0.10 to represent significant statistical heterogeneity, and an I² statistic of 60% or more to represent substantial statistical heterogeneity. We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity among studies by comparing study populations, interventions, and study methods.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed selective outcome reporting for each study by comparing outcomes specified in a protocol, research plan, or clinical trial registry with reported results. When protocols, research plans, or clinical trial registry records were not available, we assessed selective outcome reporting based on outcomes specified in the methods section of the study reports and on data collected as specified in the study design. In future updates of this review, when outcome data from 10 or more studies are included in a meta‐analysis, we will use a funnel plot to judge potential publication bias.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager 5 2014. We did not combine studies in meta‐analysis when we identified clinical or methodological heterogeneity (e.g. different anti‐VEGF agents, different outcome time points); instead we analyzed data by type of anti‐VEGF agent and time point, or, when data were not sufficient for meta‐analysis, we provided a narrative summary. We used a random‐effects model for all analyses. When the I² statistic was 60% or greater, suggesting substantial statistical heterogeneity, we assessed the direction of treatment effects across studies and the overlap of confidence intervals to determine whether meta‐analysis was appropriate. We did not adjust estimates of treatment effects to account for the multiplicity of outcomes considered in this review.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the first published version of this review, we conducted subgroup analyses of the primary outcome, as specified in the protocol, by stratifying data according to the angiographic subtype of CNV, using definitions adopted in the included trials (Vedula 2008). Because we changed the primary outcome to a gain of 15 or more letters of visual acuity for later versions of the review, and because available data were insufficient, we did not conduct these subgroup analyses; if data by angiographic subtype of CNV become available for inclusion in any future update to this review, we will include these subgroup analyses. For this review update, we combined in meta‐analysis outcome data from trials that had compared any anti‐VEGF agent versus a control other than an anti‐VEGF agent; we presented the effect estimates for individual anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, and bevacizumab) in subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

In the first published version of this review, we conducted sensitivity analyses to examine potential bias caused by missing data for participants excluded after randomization or lost to follow‐up in analyses of the primary outcome. We analyzed the primary outcome while assuming that (1) participants lost to follow‐up had lost 15 or more letters of visual acuity (worst‐case analysis); and (2) participants lost to follow‐up did not lose 15 or more letters of visual acuity at one‐year follow‐up (best‐case analysis) (Vedula 2008). Because these analyses did not alter the conclusions of this review, and because studies added in subsequent updates were too small to affect estimates of effectiveness and safety, we did not conduct sensitivity analyses for this version of the review and do not believe they would be needed in a future update.

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of studies graded as having high risk of bias on any parameter, unpublished data only, or industry funding. After assessing the studies included and the data collected, we determined that these analyses were not needed because studies within each meta‐analysis did not differ on the basis of these factors.

"Summary of findings"

We prepared "Summary of findings" tables for each comparison assessed in this review. These tables include relative and absolute effects for the following outcomes of interest at one‐year follow‐up: (1) visual acuity gain of 15 or more letters, (2) visual acuity loss of fewer than 15 letters, (3) mean change in visual acuity (number of letters), (4) reduction in central retinal thickness, (5) quality of life scores, (6) serious systemic adverse events, and (7) serious ocular adverse events. We assessed the certainty of evidence for all outcomes by using the GRADE classification system (GRADEpro 2014).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Electronic searches for the first published version of this review (conducted in August 2005, October 2006, June 2007, and February 2008) yielded a total of 1407 titles and abstracts (Vedula 2008). We selected 36 records for full‐text review and identified five trials described in 10 reports for inclusion in the review (ANCHOR 2006; EOP 1003; EOP 1004; FOCUS 2006; MARINA 2006). We excluded 16 studies (24 reports) and added two studies identified by handsearching of abstracts as awaiting classification. Table 3 lists acronyms used to refer to many studies in this review.

We identified two concurrent randomized trials that used individual participant data meta‐analyses under the acronym VISION (Gragoudas 2004) ‐ EOP 1003 (an international trial) and EOP 1004 (a North American trial). In the first published version of this review, we assessed the data from these two trials separately and analyzed them according to the original protocol of the review. We obtained data for primary and secondary outcomes for the two trials by accessing information available on the FDA website and by contacting study authors. For the 2014 update of this review (Solomon 2014), we considered the two trials as one study (VISION 2004), and we collected new data from published articles as available. We have summarized characteristics of the two individual trials in Appendix 8 and Appendix 9.

For the 2014 update, we refined the eligibility criteria to exclude studies in which researchers gave anti‐VEGF treatment in combination with other AMD treatments, and to include trials that compared two anti‐VEGF agents (i.e. head‐to‐head trials). A separate Cochrane review will cover combination therapies for AMD. Thus, in subsequent updates of the review, we did not include FOCUS 2006, which compared ranibizumab plus PDT versus PDT alone and was included in the first version of this review. Electronic searches in September 2008, April 2011, February 2013, and March 2014 yielded 4827 unique records from bibliographic databases, 403 clinical trial registrations, and 19 additional records identified by handsearching of conference abstracts. Of 153 reports from potentially relevant records, we included 12 RCTs (reported in 108 records) and excluded 39 studies (reported in 45 records). We excluded two additional studies from three records identified by handsearching and included the remaining 16 records identified by handsearching as additional reports on the included studies. We identified seven additional studies from the search of clinical trial registries ‐ one that was awaiting classification owing to insufficient information to determine eligibility, and six assessed as ongoing or completed with results not yet published.

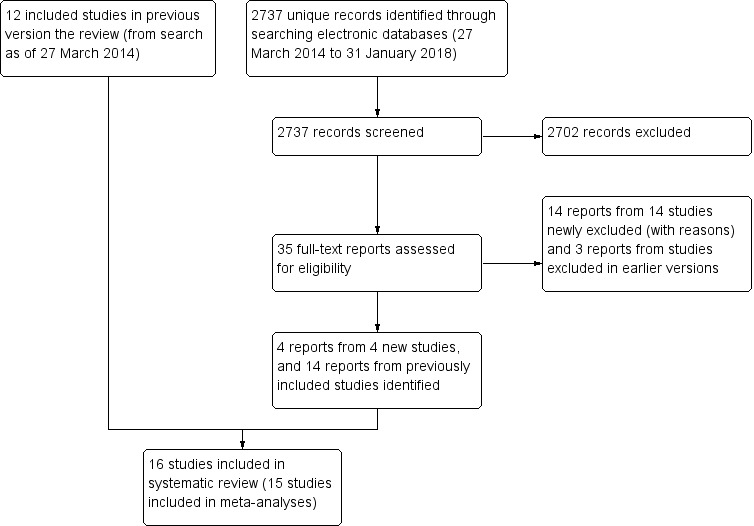

We updated the electronic searches on January 31, 2018, and identified 2737 unique records (Figure 1). We excluded 2702 records after screening titles and abstracts, and 21 records after reviewing full‐text reports. Of the 35 records not excluded, four pertained to four newly included studies (BRAMD 2016; LUCAS 2015; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014), 14 were reports from studies already included, and three were from studies excluded earlier. We had classified one newly included study as ongoing in the 2014 version of this review. Two excluded studies had been labeled as ongoing in an earlier version but were terminated before enrollment (GALATIR 2014; RATE 2011). Overall, we identified and included 16 eligible studies and one ongoing study and excluded 65 studies after review of the full‐text reports. We have listed reasons for exclusion of each of the 65 studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and described the ongoing study in the Characteristics of ongoing studies section. All but one included study had been documented in a clinical trial register.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Types of participants

This review included a total of 6347 participants from 16 RCTs; the number of participants per trial ranged from 23 to 1208. In 14 of 16 trials, investigators reported that they had randomized one eye per participant; this was unclear in 2 of 16 trials (SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014). Countries in which the trials were conducted spanned the globe: two studies were international (ANCHOR 2006; VISION 2004); four were conducted in the United States only (CATT 2011; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; Subramanian 2010), three in Austria (MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; Scholler 2014), two in the United Kingdom (ABC 2010; IVAN 2013), and one each in France (GEFAL 2013), India (Biswas 2011), the Netherlands (BRAMD 2016), Norway (LUCAS 2015), and Switzerland (SAVE‐AMD 2017). The 16 trials were similar in that all enrolled both men and women 50 years of age or older who had subfoveal CNV secondary to AMD; BRAMD 2016 also enrolled participants with juxtafoveal or extrafoveal CNV. The goal of SAVE‐AMD 2017 was to compare the effects of anti‐VEGF agents on neovascular and non‐neovascular AMD, with random assignment of participants in each cohort to ranibizumab or bevacizumab. Among the included trials, reports describe variation in types of eligible neovascular lesions (e.g. predominantly classic CNV, minimally classic CNV, occult CNV), lesion sizes, and baseline visual acuities of participants. A majority of participants in most trials were women, but one trial enrolled a greater number of men than women (Subramanian 2010).

All trials predefined visual acuity eligibility criteria for the study eye of each participant. Six studies specified the most common criterion: study eye BCVA of 20/40 to 20/320 (Snellen equivalent) in the study eye (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; MANTA 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004). BCVA eligibility ranges included somewhat better visual acuity in CATT 2011 and LUCAS 2015 (20/25 to 20/320), GEFAL 2013 (20/32 to 20/320), IVAN 2013 (20/320 or better), and Scholler 2014 (20/40 to 20/320), but potentially worse visual acuity in Sacu 2009 (20/40 to 20/800) and Subramanian 2010 (20/400 or better). In Biswas 2011, participants with a BCVA between 35 and 70 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters were eligible, but study authors did not report the test distance. In BRAMD 2016, participants with a BCVA between 20 and 78 ETDRS letters were eligible.

Eight trials included only participants who had received no previous treatment for CNV or AMD (Biswas 2011; CATT 2011; IVAN 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014). The remaining trials included participants who had received previous therapy for AMD, with certain restrictions as to type of treatment (e.g. verteporfin PDT, intravitreal injections, surgery), location of treatment, and time interval since last treatment. Six trials enrolled participants with primary or recurrent CNV in the study eye (ANCHOR 2006; BRAMD 2016; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; Subramanian 2010; VISION 2004), and one enrolled only participants with primary CNV (ABC 2010).

Among seven studies that reported the type of neovascular lesion, ANCHOR 2006 had the highest proportion of participants with predominantly classic CNV (410/423; 97%). In ABC 2010, 25% of 131 participants had predominantly classic CNV; the remaining 75% had minimally classic or occult CNV. In VISION 2004, 26% of 1208 participants had predominantly classic CNV, 36% had minimally classic CNV, and 38% had occult CNV. PIER 2008 reported proportions similar to VISION 2004, with 19% of 184 participants having predominantly classic CNV, 38% having minimally classic CNV, and 43% having occult CNV at baseline. In BRAMD 2016, 27% had predominantly classic CNV, 16% had minimally classic CNV, and 57% of 327 participants had occult CNV. Forty‐four per cent of 120 participants had occult CNV in Biswas 2011. MARINA 2006 was limited to participants with minimally classic or occult CNV and, thus, included the greatest proportion of participants with occult CNV (451/716; 63%).

Three studies that did not report neovascular lesion type described the subfoveal component of the CNV lesion in the study population. In CATT 2011 (1208 participants), 58% had CNV in the foveal center, 27% had fluid in the foveal center, 8% had hemorrhage in the foveal center, and 6% had other foveal center involvement. The distribution was similar in IVAN 2013 (628 participants), in which 54% of participants had CNV in the foveal center, 29% had hemorrhage in the foveal center, and 13% had other foveal center involvement. In LUCAS 2015 (431 participants with data), 69% had CNV in the foveal center, 80% had fluid in the foveal center, and 20% had hemorrhage in the foveal center. The three smallest studies (Sacu 2009; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Subramanian 2010), with 28, 23, and 28 participants, as well as GEFAL 2013 (501 participants) and MANTA 2013 (321 participants), did not describe the type of neovascularization nor the subfoveal component of the CNV lesion in the study population.

Six trials specified lesion size as an inclusion criterion. Five trials included participants with lesions of 12 disc areas (DAs) or smaller (1 DA = 2.54 mm², i.e. standard DA) (ABC 2010; BRAMD 2016; GEFAL 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008), and one study set four DAs as the maximum lesion size (Sacu 2009).

We have summarized in the Characteristics of included studies table additional details about each trial included in this review.

Types of interventions

We have listed in Table 4 comparisons of interventions evaluated by trials included in this review, and we summarize them here. Among the 16 included trials, we focused on two main comparisons of interventions: (1) anti‐VEGF monotherapy versus control, and (2) one anti‐VEGF monotherapy versus a different anti‐VEGF monotherapy. Of six studies that compared anti‐VEGF monotherapy versus control, one study evaluated three doses of pegaptanib versus sham injection (VISION 2004), three studies compared two doses of ranibizumab versus sham injections or PDT (ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008), and two studies compared bevacizumab with other treatments for AMD (ABC 2010; Sacu 2009). The remaining ten studies were head‐to‐head trials of bevacizumab versus ranibizumab (Biswas 2011; BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; IVAN 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014; Subramanian 2010).

2. Treatment groups in included trials.

|

Study Treatment period |

Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Intervention 4 |

| Pegaptanib vs control | ||||

|

VISION 2004 2 years; re‐randomized at end of first year |

0.3 mg pegaptanib every 6 weeks | 1.0 mg pegaptanib every 6 weeks | 3.0 mg pegaptanib every 6 weeks | Sham every 6 weeks |

| Ranibizumab vs control | ||||

|

ANCHOR 2006 2 years |

0.3 mg ranibizumab monthly plus sham verteporfin PDT | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly plus sham verteporfin PDT | Sham intravitreal injection plus verteporfin PDT | ‐ |

|

MARINA 2006 2 years |

0.3 mg ranibizumab monthly | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly | Sham intravitreal injection monthly | ‐ |

|

PIER 2008 2 years |

0.3 mg ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then every 3 months | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then every 3 months | Sham intravitreal injection monthly for 3 months, then every 3 months | ‐ |

| Bevacizumab vs control | ||||

|

ABC 2010 1 year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab given first 3 injections every 6 weeks, then as needed | Standard therapy (0.3 mg pegaptanib every 6 weeks, verteporfin PDT, or sham injection) | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Sacu 2009 1 year |

1.0 mg bevacizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | Verteporfin PDT plus same day 4 mg triamcinolone acetonide | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bevacizumab vs ranibizumab | ||||

|

CATT 2011 2 years; re‐randomized at end of first year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 1 year; at 1 year, re‐randomization to ranibizumab monthly or variable dosing | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 1 year; at 1 year, re‐randomization to ranibizumab monthly or variable dosing | 1.25 mg bevacizumab as needed after first injection for 2 years | 0.5 mg ranibizumab as needed after first injection for 2 years |

|

IVAN 2013 2 years; ongoing |

1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 2 years | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 2 years | 1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed in 3‐month cycles | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed in 3‐month cycles |

| Biswas 2011 18 months | 1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | ‐ | ‐ |

| BRAMD 2016 1 year | 1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 1 year | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 1 year | ‐ | ‐ |

|

GEFAL 2013 1 year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab; maximum of 1 injection per month | 0.5 mg ranibizumab; maximum of 1 injection per month | ‐ | ‐ |

|

LUCAS 2015 1 year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab; treat and extend protocol | 0.5 mg ranibizumab; treat and extend protocol | ‐ | ‐ |

| MANTA 2013 1 year | 1.25 mg bevacizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | 0.5 mg ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | ‐ | ‐ |

|

SAVE‐AMD 2017 1 year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab at day 1 and at week 4, then as needed | 0.5 mg ranibizumab at day 1 and at week 4, then as needed | ‐ | ‐ |

|

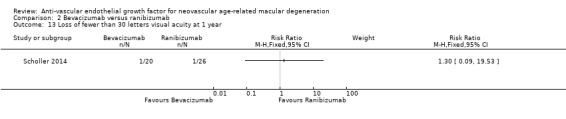

Scholler 2014 1 year |

1.25 mg bevacizumab for 3 months, at 30‐day intervals, then as needed | 0.5 mg ranibizumab for 3 months, at 30‐day intervals, then as needed | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Subramanian 2010 1 year |

0.05 mL bevacizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | 0.05 mL ranibizumab monthly for 3 months, then as needed | ‐ | ‐ |

PDT: photodynamic therapy.

Anti‐VEGF monotherapy versus control

VISION 2004 investigators compared sham injections versus intravitreous injections of pegaptanib at dosages of 0.3 mg, 1.0 mg, and 3.0 mg given every six weeks over a 48‐week period.

Three trials evaluated two different doses of ranibizumab (0.3 mg and 0.5 mg) (ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008). Control groups and the injection schedule for ranibizumab differed among the three trials. MARINA 2006 compared monthly intravitreal injection of ranibizumab (for 12 months) with sham intravitreal injections. Participants assigned to receive sham intravitreal injections in MARINA 2006 were allowed verteporfin PDT whenever the CNV lesions in the eyes became predominantly classic CNV. ANCHOR 2006 compared monthly injections of ranibizumab combined with sham PDT (for 24 months) versus verteporfin PDT and sham intravitreal ranibizumab injections. PIER 2008 compared a regimen of monthly injection of ranibizumab for three months followed by an injection every three months versus sham intravitreal injections.

Two trials evaluated bevacizumab versus control. ABC 2010 compared a 1.25 mg dose of bevacizumab versus standard therapy, which was determined by clinical evaluation and included 0.3 mg pegaptanib, verteporfin PDT, or sham injection. Sacu 2009 (a small trial) compared a 1 mg dose of bevacizumab versus verteporfin PDT combined with intravitreal triamcinolone.

Bevacizumab versus ranibizumab

Ten trials compared bevacizumab for non‐inferiority versus ranibizumab. In addition to the primary comparison of the two agents, CATT 2011 and IVAN 2013 compared monthly injections of anti‐VEGF agents with an "as‐needed" regimen after three initial injections of the assigned agent. Biswas 2011, GEFAL 2013, MANTA 2013, and Subramanian 2010 used the latter treatment regimen (a 0.5 mg dose of ranibizumab and a 1.25 mg dose of bevacizumab) to compare the two anti‐VEGF agents. BRAMD 2016 used a monthly injection schedule, and LUCAS 2015 used a "treat‐and‐extend" protocol for both drugs. In Scholler 2014, investigators did not specify the hypothesis and treated participants with an "as‐needed" regimen after three initial injections of the assigned agent. In SAVE‐AMD 2017, researchers gave intravitreous injections after the initial two injections PRN for the remainder of the one‐year follow‐up period.

Types of outcome measures

Visual acuity

BCVA formed the basis of the primary outcome for all included studies except Scholler 2014. The primary outcome for this review ‐ the proportion of participants who gained 15 or more letters of BCVA at one‐year follow‐up ‐ was the primary outcome for the ABC 2010 included study and a secondary outcome for the remaining 15 studies. The proportion of participants losing fewer than 15 letters at one year was the primary outcome for the three earliest studies (ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; VISION 2004), and it was a secondary outcome for 11 of the remaining 13 studies. The primary outcome was mean change in visual acuity at one year for eight studies (BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; PIER 2008; Sacu 2009; Subramanian 2010), and the primary outcome was mean change in visual acuity at 18 months for one study (Biswas 2011). Five of the remaining studies reported mean change in visual acuity as a secondary outcome. The primary outcome for IVAN 2013 was best‐corrected distance visual acuity at two‐year follow‐up; we did not analyze mean BCVA (as opposed to mean change from baseline) as an outcome for this review.

Some included studies reported other visual acuity outcomes relevant to this review. Five studies reported loss of fewer than 30 letters of visual acuity (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; Subramanian 2010; VISION 2004); eight studies reported BCVA better than 20/200 (ANCHOR 2006; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; IVAN 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; Subramanian 2010; VISION 2004); and four studies reported maintenance of visual acuity (defined as a gain of zero or more letters) (ANCHOR 2006; Sacu 2009; Subramanian 2010; VISION 2004). Investigators in included studies reported several other visual acuity outcomes that we did not consider in this review.

All studies measured visual acuity on a LogMAR scale, typically using ETDRS charts. Each line on the ETDRS chart consists of five letters; thus, a change of 15 letters approximates a three‐line change (0.3 LogMAR change) in visual acuity. Researchers reported the outcome for visual acuity of 20/200 or better as the Snellen equivalent.

Visual function

Five studies assessed visual function outcomes. ABC 2010 specified contrast sensitivity and reading ability as secondary outcomes. IVAN 2013 specified contrast sensitivity, near visual acuity, and reading index outcomes as secondary outcomes. We identified one conference abstract that reported contrast sensitivity outcomes for ANCHOR 2006, MARINA 2006, and PIER 2008.

Eleven studies did not report visual function outcomes (Biswas 2011; BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014; Subramanian 2010; VISION 2004).

Morphologic outcomes

All studies included at least one measure related to morphologic characteristics of neovascular lesions in study eyes. In many cases, publications or conference abstracts did not provide sufficient data for informative analysis of these outcomes. When possible, we used data provided by primary investigators, or we asked primary investigators to confirm data extracted from graphs in study reports. We have not reported data derived from graphs included in study reports unless we received confirmation of the data from study investigators.

All studies except SAVE‐AMD 2017 used fluorescein angiography to monitor lesion activity; that study used OCT to monitor lesion status. Six studies also used fundus photography (ANCHOR 2006; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004), and two studies used ICG angiography (GEFAL 2013; Sacu 2009). Six studies evaluated mean change in CNV size by fluorescein angiography (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; GEFAL 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004), and eight studies used fluorescein angiography to evaluate mean change in the size of neovascular lesions (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; CATT 2011; IVAN 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; Scholler 2014; VISION 2004).

The earliest study included in the review did not use OCT for assessment of subretinal characteristics of eyes with neovascular AMD (VISION 2004). The next three studies, which were conducted chronologically (ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008), used OCT to assess a subset of study participants. The 12 most recently reported studies used OCT for all study participants and specified at least one OCT measure as a primary or secondary outcome (ABC 2010; Biswas 2011; BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; IVAN 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014; Subramanian 2010). All studies that used OCT assessed mean change in central retinal thickness (CRT) from baseline. We considered central macular thickness, central foveal thickness, and center point thickness as interchangeable terms for CRT.

Individual studies reported other morphologic outcomes, such as area of CNV leakage and subretinal fluid, but we did not include these outcomes in this review.

Quality of life outcomes

Four studies evaluated vision‐specific quality of life using the 25‐item National Eye Institute‐Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEI‐VFQ) (ANCHOR 2006; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004). The NEI‐VFQ, which was administered by an interviewer, relies on patient‐reported responses to specific visual function questions to calculate overall and subscale scores, which can range from 0 to 100, with higher values representing better visual function.

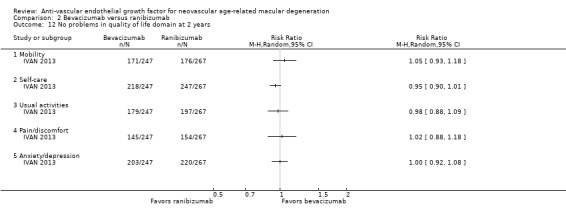

In one study (IVAN 2013), participants completed the EuroQoL Group health‐related quality of life assessment (EQ‐5D). The EQ‐5D converts participant responses to specific health questions using scales of 1 to 3, on which 1 represents no health problems, 2 represents moderate health problems, and 3 represents extreme health problems. Investigators then summarize scores for each of the five subscale domains (mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) into a single index score ranging from ‐0.59 to 1.00, with 1.00 representing no health problems. Both the NEI‐VFQ and the EQ‐5D are validated tools that can be used to assess quality of life outcomes.

The remaining studies either did not measure or have not reported quality of life outcomes (ABC 2010; Biswas 2011; BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; SAVE‐AMD 2017; Scholler 2014; Subramanian 2010).

Economic outcomes

Two studies included economic‐related outcomes as prespecified secondary outcomes. CATT 2011 evaluated annual costs associated with each treatment group. IVAN 2013 evaluated cumulative resource use and costs for each treatment group.

Adverse events

Seven studies reported individual ocular and non‐ocular adverse events up to one‐year follow‐up (ABC 2010; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; Sacu 2009; Scholler 2014; Subramanian 2010), one study up to 18‐month follow‐up (Biswas 2011), five studies up to five‐year follow‐up (ANCHOR 2006; CATT 2011; IVAN 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008), and one study up to seven‐year follow‐up (VISION 2004). BRAMD 2016 investigators did not report ocular adverse events but reported major systemic adverse events. SAVE‐AMD 2017 investigators reported that there was "no serious ocular adverse event (e.g. endophthalmitis, retina detachment, and lens damage)" during the 12‐month follow‐up period.

Excluded studies

We excluded 65 studies after completing full‐text assessments: 23 studies were not RCTs; 13 followed participants for less than one year; nine were dose‐response studies that included no control or comparator arm; six compared combination therapies in which treatment groups received the same anti‐VEGF therapy; two did not administer anti‐VEGF agents via intravitreous injection; one did not include participants with neovascular AMD; ten evaluated agents that were not eligible for this review (aflibercept, brolucizumab, and pazopanib eye drops); one did not report any outcome targeted for this review; and two potentially relevant studies were terminated before enrollment.

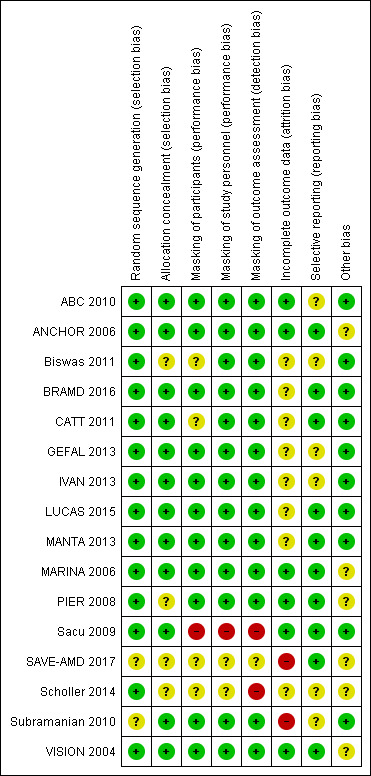

Risk of bias in included studies

We have provided assessments of risks of bias for each included study at the end of each respective Characteristics of included studies table. When we needed unpublished information to assess the risk of bias for any given parameter, we contacted primary investigators for additional information. We have documented these instances together with investigators' responses in the Characteristics of included studies table. Figure 2 summarizes "Risk of bias" assessments for all 16 studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Overall, the included studies were at low risk of selection bias. Reports from 14 of the 16 studies described methods of random sequence generation that we judged to confer low risk of bias; SAVE‐AMD 2017 investigators and Subramanian 2010 did not describe the methods used in sufficient detail for us to assess risk of bias in this domain. Six studies used dynamic randomization, the method used most commonly for random sequence generation (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; BRAMD 2016; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004). Four studies used permuted block randomization designs (CATT 2011; IVAN 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013), three used random number tables or lists (Biswas 2011; GEFAL 2013; Scholler 2014), and one reported only use of a computer‐randomized schema (Sacu 2009).

Investigators in 12 of the 16 trials reported adequate allocation concealment. For Biswas 2011, the report was unclear as to whether the randomization sequence, determined by random numbers tables generated before study enrollment, was concealed or was made available to study investigators. PIER 2008 did not describe how assignments were allocated, and we were unable to make an assessment by using only available information. Eight studies employed a third party or a central co‐ordinating center (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; GEFAL 2013; LUCAS 2015; MANTA 2013; MARINA 2006; Sacu 2009; Subramanian 2010), and four studies used a computer‐based portal for allocation concealment (BRAMD 2016; CATT 2011; IVAN 2013; VISION 2004).

Communication with investigators from Biswas 2011, PIER 2008,SAVE‐AMD 2017, and Subramanian 2010 yielded no additional information about methods used to assess risks of selection bias (email communication).

Masking (performance bias and detection bias)

We judged most of the included studies to be at low risk of performance bias and detection bias. Only one study was an open‐label study that employed no form of masking (Sacu 2009). CATT 2011 initially masked participants to the drug (not to the injection protocol), but participants may have become aware of treatment assignments through billing records. Biswas 2011, SAVE‐AMD 2017, and Scholler 2014 did not report whether study participants were masked. Biswas 2011 and CATT 2011 masked personnel and outcome assessors. The remaining 11 studies masked study participants, personnel (other than personnel directly administering treatment), and outcome assessors; thus, we assessed these studies as being at low risk of performance bias and detection bias. Investigators in studies that compared intravitreous injections versus no injections most commonly used sham injections when participants were not assigned or did not require an injection. In head‐to‐head studies of ranibizumab versus bevacizumab, researchers masked participants to their assigned treatment group. To minimize detection bias, study investigators who were involved in assessing outcomes were separate from treating physicians and were masked to treatment groups, with the exception of Sacu 2009, which provided no masking. SAVE‐AMD 2017 and Scholler 2014 provided no information on masking of study participants, study personnel, or outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

In all 16 trials, few participants missed the follow‐up examination specified as the primary time for assessing the study's primary outcome or were not treated in accord with the randomized treatment assignment. In nine trials, rates of loss to follow‐up at primary follow‐up visits were less than 15%; BRAMD 2016, GEFAL 2013, LUCAS 2015, MANTA 2013, SAVE‐AMD 2017, and Subramanian 2010 had 16% to 25% of participants with missing outcome data. Losses to follow‐up were evenly balanced between treatment groups in the included studies.

Eight trials included in this review analyzed the data using methods designed to overcome, in part, loss of information due to missed follow‐up examinations. Seven of these eight trials used the last observation carried forward method to impute missing data (ABC 2010; ANCHOR 2006; BRAMD 2016; MANTA 2013; MARINA 2006; PIER 2008; VISION 2004), and the eighth trial did not report the method used to impute data for one participant with missing data (Sacu 2009). The remaining eight trials reported available case data and included in the analysis only participants with data: 87% in Biswas 2011, 91.5% in CATT 2011, 81% in GEFAL 2013, 89% in IVAN 2013, 84% in LUCAS 2015, 81% in SAVE‐AMD 2017, 83% in Scholler 2014, and 79% in Subramanian 2010. Investigators in all trials reported that they had analyzed data for participants by assigned treatment arms. Analyses using simple imputation methods or available case data assume that participants are lost to follow‐up at random; bias may be introduced when this assumption is not true, with greater risk of bias associated with higher rates of missing data.

Selective reporting

With the exception of Biswas 2011, we identified design articles, protocols, or clinical trial registrations for 15 of the included studies. We judged 11 of these 15 trials to be free of reporting bias on the basis of consistency between study outcomes defined in protocols and clinical trial registrations and those reported in study results papers. Researchers did not specify quality of life outcomes, and we identified no report on quality of life findings from Subramanian 2010. We found no data on reading ability outcomes, which ABC 2010 specified as secondary outcomes. Published articles on one‐year and two‐year results did not report findings for three outcomes specified in the protocol for IVAN 2013: treatment satisfaction, survival free from treatment failure, and exploratory (serum) analysis. Differences in outcomes between trial registration and published one‐year results of GEFAL 2013 included the following: differences in details of outcome specifications (e.g. efficacy of treatments vs proportion of participants with a gain of 15 or more letters of visual acuity); outcomes specified in the trial register but not reported in publications; and an outcome that was not mentioned in the trial registration document.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered various other aspects of trial design and reporting, trial sponsorship, and financial interests of investigators as other potential sources of bias.

Pharmaceutical companies marketing the study drugs under investigation sponsored ANCHOR 2006, MARINA 2006, PIER 2008, and VISION 2004, and submitted data from these trials to the FDA to obtain approval for ranibizumab and pegaptanib. In addition, pharmaceutical company sponsors had important roles in trial design, analysis, and reporting. Some investigators from other trials reported that they received trial agents or financial support from pharmaceutical companies; however, because the companies did not directly sponsor these trials, we did not judge them to be at risk of bias for this domain (CATT 2011; GEFAL 2013; IVAN 2013; Scholler 2014). We observed no other potential sources of bias for the remaining eight studies.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: anti‐VEGF treatment versus control.

| Anti‐VEGF treatment versus control for neovascular age‐related macular degeneration | ||||||

|

Participant or population: people with neovascular age‐related macular degeneration Settings: clinical centers Intervention: intravitreal injections of anti‐VEGF agents (pegaptanib, ranibizumab, or bevacizumab) Control: standard therapy at the time of the trial (sham injections, verteporfin photodynamic therapy with or without triamcinolone acetonide, or intravitreal injections of pegaptanib) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Anti‐VEGF treatment | |||||

| Gain of 15 or more letters visual acuity at 1 year | 43 per 1000 | 179 per 1000 (99 to 322) | RR 4.19 (2.32 to 7.55) | 2667 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Loss of fewer than 15 letters visual acuity at 1 year | 599 per 1000 | 838 per 1000 (760 to 928) |

RR 1.40 (1.27 to 1.55) |

2667 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Mean change in visual acuity at 1 year (number of letters) | Mean change across control groups ranged from a loss of 10 to 16 letters | See comment | See comment | 2508 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | Owing to substantial statistical heterogeneity between pegaptanib and ranibizumab subgroups, we did not combine data across subgroups Mean change in visual acuity in pegaptanib groups was on average 6.72 more letters gained (95% CI 4.43 letters to 9.01 letters); MD 6.72 (95% CI 4.43 to 9.01) Mean change in visual acuity in ranibizumab groups was on average 17.80 more letters gained (95% CI 15.95 letters to 19.65 letters); MD 17.80 (95% CI 15.95 to 19.65) Mean change from baseline in visual acuity was 7.0 letters in bevacizumab group and ‐9.4 letters in control group in 1 study. The second study reported that participants in bevacizumab group gained 8 letters on average and participants in control group lost 3 letters on average |

| Reduction in central retinal thickness at 1 year | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | We were unable to find data on central retinal thickness in reports from the only trial comparing pegaptanib with control and from any of the 3 included trials comparing ranibizumab with control Mean change was ‐91 μm in bevacizumab group and ‐55 μm in control group in one study, and ‐113 μm in bevacizumab group and ‐72 μm in control group in the other study |

| Mean change in vision‐related quality of life | Mean change across control groups in vision‐related quality of life scores ranged from ‐3 to 2 points | Mean change across control groups in vision‐related quality of life scores ranged from 5 to 7 points | MD 6.69 (3.38 to 9.99) | 1134 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Use of the NEI‐VFQ questionnaire with a 10‐point difference considered clinically meaningful |

| Serious systemic adverse events at 1 year | Range of 5 to 83 per 1000 for various systemic adverse events | Range of 0 to 55 per 1000 for various systemic adverse events | Range of RR 0.17 (0.01 to 4.24) to 2.08 (0.23 to 18.45) | 2667 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | |

| Serious ocular adverse events at 1 year | Range of 0 to 68 per 1000 for various ocular adverse events | Range of 3 to 118 per 1000 for various ocular adverse events | Range of RR 0.52 (0.03 to 8.25) to 2.71 (1.36 to 5.42) | 2667 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is estimated by the proportion with the event in the control group. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Anti‐VEGF: anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; NEI‐VFQ: National Eye Institute‐Visual Functioning Questionnaire; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded (‐1) owing to imprecision in the confidence interval. bDowngraded (‐1) owing to inconsistency in effect between types of anti‐VEGF agents. cAdverse events downgraded to moderate quality as not all eligible trials reported all types of adverse events, and numbers were small (< 1%) for many specific adverse events.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: bevacizumab versus ranibizumab.

| Bevacizumab versus ranibizumab for neovascular age‐related macular degeneration | ||||||

|