Abstract

Background

Considerable progress has been made in dengue management, however the lack of appropriate predictors of severity has led to huge number of unwanted admissions mostly decided on the grounds of warning signs. Apoptosis related mediators, among others, are known to correlate with severe dengue (SD) although no predictive validity is established. The objective of this study was to investigate the association of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) with SD, and evaluate its prognostic value in SD prediction at acute phase.

Methods

This was a hospital-based prospective cohort study conducted in Vietnam. All the recruited patients were required to be admitted to the hospital and were strictly monitored for various laboratory and clinical parameters (including progression to SD) until discharged. Plasma samples collected during acute phase (6–48 h before defervescence) were used to estimate the level of cfDNA.

Results

Of the 61 dengue patients, SD patients (n = 8) developed shock syndrome in 4.8 days (95% CI 3.7–5.4) after the fever onset. Plasma cfDNA levels before the defervescence of SD patients were significantly higher than the non-SD group (p = 0.0493). From the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, a cut-off of > 36.9 ng/mL was able to predict SD with a good sensitivity (87.5%), specificity (54.7%), and area under the curve (AUC) (0.72, 95% CI 0.55–0.88; p = 0.0493).

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings suggest that cfDNA could serve as a potential prognostic biomarker of SD. Studies with cfDNA kinetics and its combination with other biomarkers and clinical parameters would further improve the diagnostic ability for SD.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12941-019-0309-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Severe dengue, Cell-free DNA, Prognostic biomarker, Dengue severity predictor

Background

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease of the tropics/subtropics caused by any of the four dengue virus serotypes (DENV-1 through -4) which is responsible for at least two million severe cases among the 96 million apparent infections every year globally [1–3]. Dengue clinical spectrum ranges from mild to severe dengue (SD). SD is described by the presence of severe plasma leakage, severe bleeding and organ impairment [2]. Mechanisms of dengue pathogenesis and severity are not clear, although several host (e.g. primary vs secondary immune response) and viral factors are considered accountable for progression to SD [3, 4].

No specific treatment is currently available for dengue and the recently licensed vaccine has limited efficacy [5]. Moreover, its geographical expansion has resulted in increased frequency and magnitude of epidemics and the escalating number of SD patients led to a huge economic burden worldwide [3]. Although the use of ‘warning signs’ has contributed significantly in clinical management, it is difficult to accurately recognize SD patients in early phase of disease using these warnings signs [6, 7]. Apparently, the use of warning signs as proxy indicators for admission has added extra burden to the hospitals, and more importantly, some dengue patients without warning signs may also progress to SD—a serious drawback of this system [2, 3]. Therefore, from the patient management point of view, early prediction of dengue severity could be a game changer in reducing hospital burden and mortality while enhancing the quality of care to the severe patients [8]. Unfortunately, there is no reliable routine prognostic test available yet [9]. There have been growing efforts made on the discovery of predictors based on severity biomarkers alone or in combination with dengue clinical signs [8–11], however these are either not validated clinically or the evidence is not adequate for clinical application [12–14].

Therefore, the quest/validation of biomarkers in dengue is well grounded. In the SD biomarker pipeline, circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) can be considered one of the potential candidates based on the evidences previously reported in other health conditions as highlighted herein. cfDNA is a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (mitochondrial or nuclear) fragment released in extracellular fluids from various cells [15, 16]. Apoptosis is believed to be the major source of cfDNA in plasma [17], although the exact mechanism of its generation is still enigmatic. Whatever the source of cfDNA, it could be a new avenue in dengue predictor studies. First, because cfDNA has been extensively studied in various cancer conditions [18, 19] and implemented as a potential marker [19–21]. Despite its application in cancer conditions as a biomarker, its utility is not adequately explored in viral diseases. Second, the association between apoptosis and dengue severity has been reported [22, 23], and in a preliminary study, our group indicated that the cfDNA level increased in severe patients, however its SD predictive potential was not validated in the early stage of the disease [24]. Therefore, it is important to identify the potential diagnostic role of cfDNA in early recognition of SD among dengue patients. In this study, we aimed to investigate the association of plasma cfDNA with SD, and evaluate whether cfDNA could be a predictive biomarker for SD at early acute phase of illness.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Pasteur Institute in Ho Chi Minh City (PIHCM), Vietnam (No. 602/QD-Pas 27/12/10), and Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan (No. 11063072) and conducted according to Helsinki Declaration with a written informed consent being obtained from each study participant and/or parent/primary caregiver.

Study design and enrollment

This study was carried out using samples from dengue patients enrolled in a hospital-based prospective study at Nguyen Dinh Chieu Hospital, Ben Tre province, Vietnam from July 2011 to May 2013. Five years old or older patients admitted with a suspected acute dengue infection, presenting with acute onset of fever (≥ 38 °C within the last 72 h) and with no severe symptoms before hospital admission were included. Patients with known evidence or history of chronic diseases, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, respiratory disease, hepatitis, kidney impairment, gastric or duodenal ulcer, diabetes, osteoporosis, glaucoma, immunodeficiency disease, significant anemia (hemoglobin < 8 g/L), and immunosuppressive drugs use within the last two weeks of enrollment were excluded.

Patient admission and diagnosis

All the recruited patients were required to be admitted in hospital for close monitoring despite no severe signs appearing at the time of admission. Non-structural (NS)-1 antigen test (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Marnes-la-Coquette, France) positive patients were further confirmed by reverse transcription (RT) PCR and in-house IgM antibody capture enzyme linked immuno-sorbent assay (MAC-ELISA) or anti-dengue IgM/IgG ELISA as described previously (Additional file 1: Table S1) [24–27]. Primary and secondary dengue infections were determined using IgM/IgG ratios in acute and convalescent sera by capture ELISAs (Pasteur Institute, Vietnam). Secondary infection was defined when the IgM/IgG ratio was < 1.8 or had a positive IgG result in acute phase with subsequent ≥ 4- fold rise in convalescent sera [2, 24, 26]. Likewise, DENV IgM positive case was considered to be primary infection when the ratio of IgM/IgG was ≥ 1.8 or had a negative IgG result in acute phase [2, 28]. NS1 positive patients (except 2 NS1 negative but RT-PCR positive patients) were recruited to ensure active (current) DENV infection (Additional file 1: Table S1). Also, anti-DENV IgG detection (Pasteur Institute) remained helpful to rule out past infection [24, 26, 29]. Therefore, we considered all the included patients had active DENV infection. With thorough clinical examinations and DENV specific assays (antigen, antibody and viral RNA) in a dengue endemic setting, it was less likely to have infections other than DENV.

Patient monitoring for disease progression and shock

All the admitted patients were strictly monitored everyday by experienced physician(s) for disease progression (clinical course) until discharge. Patients received standard treatment according to the guidelines of Ministry of Health, Vietnam. All the clinical data were duly recorded, which include but not limited to blood collection time, clinical manifestations (vital signs, vomiting, hemorrhagic tendencies (such as mucosal, gastrointestinal, menstruation, nosebleed, etc.), liver enlargement, and progression to severe syndromes, e.g. shock), treatment history, and laboratory parameters (such as hematocrit level, platelet count, leukocyte count, etc.).

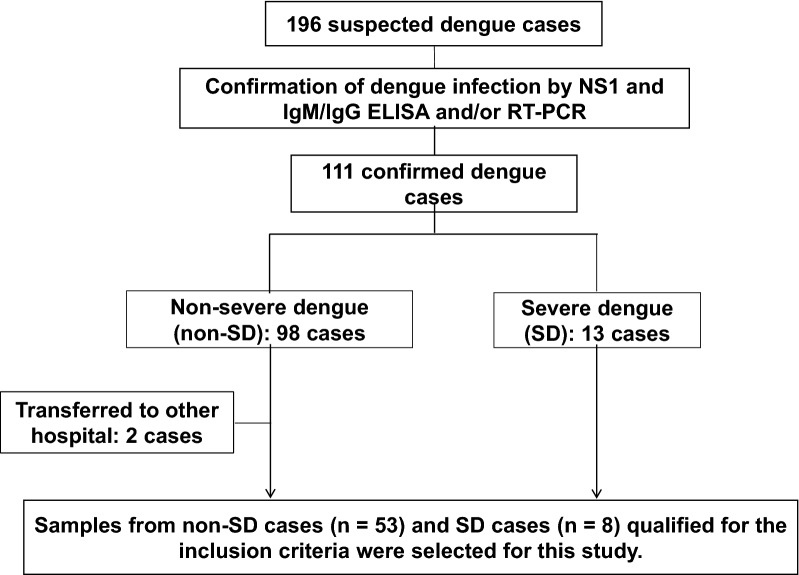

All the eligible patients admitted and monitored were classified according to the classification criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO)-2009 for severity grading (Fig. 1). Patients who developed severe manifestations like shock syndrome were considered as SD according to the WHO-2009 criteria while those who did not develop any severe forms were classified as non-SD (dengue without and with warning signs) [2]. Clinical outcome (e.g. shock) was then linked back to patient data.

Fig. 1.

Flow-diagram of the case selection and processing. NS1, Non-structural protein 1; ELISA, Enzyme linked immuno-sorbent assay; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction

Acute plasma samples (collected 6–48 h before defervescence) from eligible dengue patients were selected for this study and stored at − 80 °C. Additionally, control blood samples were taken from nine healthy Vietnamese donors (from the same Kinh ethnic group to eliminate potential ethnic and demographic bias) without current or recent history of fever or any other disease symptoms. Plasma samples from healthy volunteers were tested for DENV NS1 antigen, RNA and IgM antibody to rule out DENV infection as described above. These healthy plasma samples were exclusively used in the preparation of standard curve required for quantitative measurement of cfDNA in patient’s plasma samples as described elsewhere [24].

Plasma cfDNA measurements

The cfDNA levels of acute-phase plasma samples were measured by Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Reagent and Kits (Invitrogen, USA) with some modifications [30, 31]. With PicoGreen, dsDNA can be quantitated with very minimal interference (< 10%) by single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA in the sample [32]. Briefly, 3 μL of patient’s plasma was added into each micro-well containing 100 μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) followed by addition of 100 μL of PicoGreen working solution. Reaction mixture was dark incubated for 5 min and fluorescence was measured (at 485 nm excitation, 535 nm emission wavelengths) using a fluorescence microplate reader (Perkin Elmer Wallac 1420). Standard curve (Additional file 1: Fig. S1) was created with known concentrations of Lambda DNA prepared in TE, 3 μL of which was added to well containing 97 μL TE and 3 μL healthy plasma. Healthy plasma (3 μL) in TE buffer (100 μL) was used as background. To resemble the plasma sample physiology, pooled plasma from nine healthy donors (with negligible DNA concentration) was used in TE buffer to prepare the standard curve. Each assay was performed in duplicate. Perfect linearity of the standard curve was observed in a range of 6.9–443.4 ng/mL. Concentrations of unknown plasma samples were determined by using the linear equation.

Data analysis

Patient’s demographic, clinical and laboratory data were entered into spread sheet (master file) and underwent data cleaning/verification. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism software version 6.05. The cfDNA levels of each severity group were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Differences between two groups were analyzed by using Mann–Whitney U test. Cell counts and cfDNA concentration data were also subjected to Spearman’s correlation test. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant for all analyses. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was made and the area under ROC curve (AUC) was analysed to determine the discriminatory performance of cfDNA in predicting SD.

Results

Demographic and clinical profiles

The age of the dengue patients in our cohort ranged from 6 to 44 years (children ≤ 15 years, 65.6%), and the vast majority (78.7%) had secondary infection (Table 1). No significant difference was observed between SD and non-SD patients for most demographic (age, sex) and clinical (abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, etc.) features, and laboratory findings (DENV serotypes, platelet counts).

Table 1.

Clinical features and plasma cfDNA levels in patients with severe and non-severe dengue

| Characteristics | Non-SD (n = 53) | SD (n = 8) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic features | |||

| Age—median year (IQR) | 12.0 (10.0–18.0) | 12.5 (10.0–17.3) | 0.9456 |

| Male (%) | 22 (41.5) | 3 (37.5) | 1 |

| Clinical symptoms, physical signs and intervention | |||

| Abdominal pain (%) | 30 (56.6) | 6 (75.0) | 0.4525 |

| Persistent vomiting (%) | 4 (7.5) | 2 (25.0) | 0.1731 |

| Mucosal bleeding (%) | 7 (13.2) | 3 (37.5) | 0.1154 |

| Liver enlargement > 2 cm (%) | 1 (1.89) | 1 (12.5) | 0.247 |

| Narrow pulse pressure | 0 | 8 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| Shock manifestation | 0 | 8 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| Infusion (Ringer’s lactate) | 37 (69.8) | 8 (100) | 0.0097 |

| Laboratory test | |||

| Secondary infection (%) | 41 (77.36) | 7 (87.5) | 1 |

| PLT (× 103/μL)—median (IQR)a | 123.0 (92.0–165.5) | 101.0 (48.3–147.3) | 0.2784 |

| Dengue serotype | |||

| DENV-1 (%) | 9 (17.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 |

| DENV-2 (%) | 14 (26.4) | 3 (37.5) | 0.674 |

| DENV-3 (%) | 3 (5.7) | 2 (25.0) | 0.1239 |

| DENV-4 (%) | 15 (28.3) | 1 (12.5) | 0.6681 |

| Unknown (%) | 19 (35.8) | 2 (25.0) | 0.7028 |

| Day of sampling from fever onset—median day (IQR) | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | 0.7368 |

| Time of sampling before defervescence—median hour (IQR) | 20.0 (14.0–28.0) | 15.5 (11.3–23.8) | 0.2931 |

| Plasma cfDNA levels, median (IQR), ng/mL | 35.4 (24.4–51.6) | 61.4 (38.3–110.5) | 0.0493 |

SD, severe dengue; non-SD, non-severe dengue; IQR, interquartile range; PLT, platelet count; DENV, dengue virus; cfDNA, cell-free DNA

* Difference between categorical variables (sex, infection type, clinical signs, etc.) was determined by χ2 test or Fishers-exact test as appropriate, while the difference between continuous variables (age, platelet counts, sampling duration and cfDNA levels) was calculated by Mann–Whitney U test (between two groups) as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant

aSamples collected from 6 to 48 h before defervescence. PLT count for four patients was missing

Dengue disease progression and clinical outcomes

Of the eligible dengue patients (n = 61) included in the present study, eight patients developed severe manifestations (shock syndrome) while the rest 53 remained as non-SD (Fig. 1) during the in-patient follow up. Detailed clinical information of each patient has been provided in supplementary materials as Additional file 2. Among the SD patients, defervescence was observed after 4.3 days (95% CI: 3.6–5.0; range: 3–5 days) of fever, and all eight patients developed shock between 3 and 6 days (mean [95% CI]: 4.8 days [3.7–5.4]) after the fever onset. The average time interval between defervescence and shock was 17.2 h (95% CI: 9.2–25.2; range: 8–26 h). All shock patients but one had secondary infection, and the shock patient with primary infection had DENV-1 and -3 co-infection.

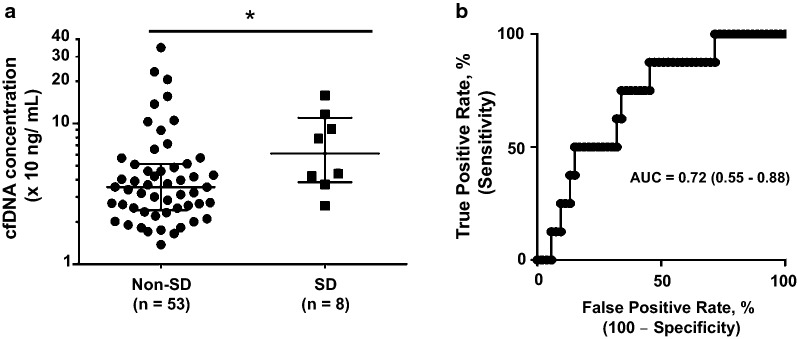

Plasma cfDNA levels remained significantly higher in SD patients during acute phase of illness

The acute plasma cfDNA levels were significantly higher (p = 0.0493) in the SD group [median (IQR): 61.4 ng/mL (38.3–110.5)] compared to the non-SD group [35.4 ng/mL (24.4–51.6)] (Table 1 and Fig. 2a). Plasma cfDNA had an AUC of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.55–0.88; p = 0.0493) in predicting SD (Fig. 2b). With a cut-off value > 36.85 ng/mL, cfDNA demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 87.5% (95% CI: 47.4%–99.7%) and 54.7% (40.4%–68.4%) respectively, in predicting SD among the total dengue patients.

Fig. 2.

Acute phase plasma cfDNA levels associated with dengue severity. a Plasma cfDNA levels in patients with non-severe dengue (n = 53) and severe dengue (n = 8). The error bars represent the median and (*) indicates p < 0.05 by Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. cfDNA concentration is expressed on a log scale (Y-axis). b ROC curve of plasma cfDNA levels as a predictor of SD. Plasma cfDNA had an AUC of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.55–0.88; p = 0.0493). cfDNA, Cell-free DNA; ROC, Receiver operating characteristics; AUC, Area under the ROC curve

We did not find significant difference in the overall cfDNA level between primary and secondary DENV infection, and between the SD and non-SD secondary infections (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). This suggests that cfDNA does not vary between primary and secondary dengue infections.

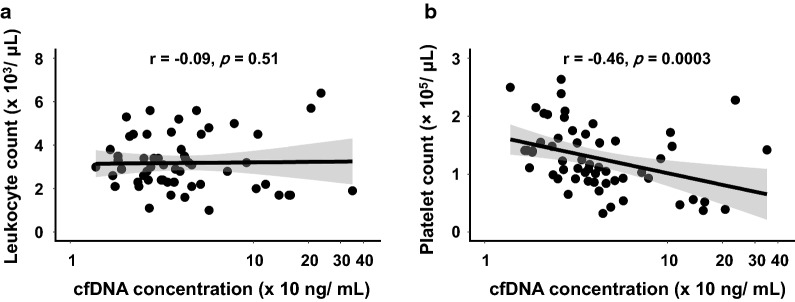

On further analysis, we also observed significant correlation between cfDNA concentration and platelet count (r = − 0.46, p = 0.0003) but not the leukocyte count (r = − 0.09, p = 0.51) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between plasma cfDNA level and leukocyte or platelet count in dengue patients. Leukocyte count (a) or platelet count (b) was plotted against the plasma cfDNA concentration (ng/mL) to determine their correlation by Spearman’s method. Correlation coefficient (r) of 1 or − 1 indicates a perfect correlation between two variables, while r = 0 indicates no correlation. In the scatter plot graph, data is presented as correlation line (bold straight line) and 95% confidence interval (CI) (shaded area). cfDNA concentration is expressed on a log scale (X-axis). Statistically significant correlation was considered, when p < 0.05. Leukocyte and platelet count data were missing for 4 cases, and hence the correlation was performed using data from 57 cases

Discussion

Here, we report the potential of plasma cfDNA as an early predictor of SD along with clinical and laboratory findings in our cohorts. Identification of reliable biomarkers/predictors is crucial in dengue because neither the sole dependency on warning signs described in WHO guidelines [2, 33], nor other proposed algorithms are sufficient to predict SD during the early stage of illness [12–14].

We found significantly elevated levels of cfDNA (6–48 h before defervescence) in dengue patients who later progressed to SD compared to those who did not. More precisely, in predicting SD, the acute cfDNA alone exhibited a good sensitivity and specificity with an AUC > 0.7 (Fig. 2b) which is considered as acceptable predictive performance [34]. Still, warning signs are widely used in recognizing patients at risk of developing SD despite their subjective nature (some signs) and late appearance in the disease course [2]. This halts early SD detection and timely management, and is also criticized for over-estimation of SD [33]. In that sense, cfDNA is a simple tool, likely makes the SD prediction more practical and explicit as anticipated in our study previously [24]. Moreover, the use of cfDNA in combination with other early signs probably further enhance the SD prediction. Several candidates have been studied to explore severity predictors in dengue such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tryptase and chymase [35, 36], transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b), and VEGF receptor-2 [9], cytokines (IL-10, IFN-γ) [8] and plasma IgE levels [11]. For instance, we recently reported the ratio of DENV specific IgE and total IgE (S/T ratio) as a potential candidate predictor (sensitivity/specificity, 75%/68%) [11]. In our preliminary analysis, another candidate biomarker TGF-b-induced protein (TGFBIp) has also shown some promising results (data not shown). Therefore, the combination of cfDNA with other potential candidate biomarkers [8, 9, 11, 35, 36] or clinical signs is worthwhile when applied to recently proposed prediction models [12–14, 37]. Yet, none of these this combination was investigated in our cohort partly due to the small number of samples in the severe group, as we enrolled patients at early state which resulted into fewer patients in the SD group.

Regardless of the difference in cfDNA levels between SD and non-SD groups, the underlying mechanism and its role in the SD pathogenesis are not clear. Apoptosis being the major source of cfDNA in bloodstream [17] and its presence in various tissues from fatal dengue patients suggests involvement of apoptosis in SD pathogenesis [22]. The apoptotic microvascular endothelial cells probably play roles in vascular permeability—a hallmark of SD [22]. The level of peripheral mononuclear cell apoptosis around defervescence also well correlated with SD in children [23]. In addition, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) [38], TGF-beta [39], TNF-alpha, nitric oxide and NS1 [4, 40] related to apoptosis were reported at increased levels in SD patients’ samples, further supporting the role of apoptosis in SD and cfDNA as its proxy indicator. Undoubtedly, the knowledge on the source of this cfDNA would aid in the further understanding of pathogenesis too.

We also found a significant correlation between decreasing platelet count and increasing cfDNA concentration in dengue patients. Probably, it is associated with binding and subsequent platelet activation by DENV as reported previously [2, 41, 42]. Platelet activation is believed to release mitochondria [43], leading to elevated mitochondrial DNA in plasma [44], which in turn perhaps contributed to high cfDNA levels in dengue patients with decreasing platelet counts. Mitochondrial DNA released from platelet is also a potent inflammatory trigger which causes cytokines release and systematic inflammation [43]. This pro-inflammatory response might also play a role in dengue clinical outcomes.

Besides, the failure to remove cfDNA from the bloodstream was also explained by severe multi-organ dysfunctions (liver and kidneys), one of the dengue severe forms [24], however the SD patients in this study did not present these manifestations. Since the half-life of cfDNA in the circulation is short [21], the levels of cfDNA in dengue patients might be fluctuated over time. Though all the samples in this study were selected early before defervescence/shock, the sampling time frame might be broad. Therefore, additional studies to investigate the kinetics of cfDNA in different time points of the disease course will be informative to select the best sampling time for measuring cfDNA to precisely predict SD. As a limitation, we did not measure the cfDNA in other severe conditions/infections, thus it requires cautious interpretation among dengue patients co-infected with other pathogens.

We are aware that the cfDNA assay may not be promptly applicable to the clinical settings in its current form and it certainly requires additional prospective studies in larger cohorts before moving to clinical application. This cfDNA assay is very simple, rapid, inexpensive and efficient (3 μL plasma volume). We have further simplified this assay by eliminating the need of enzymatic digestion used previously [24]. Requirement of a fluorescence microplate reader could limit its wide application for now. However, we believe that cfDNA is one of the simple assays and with the current technological advancement, it is very likely to be developed as simpler formats (even field-friendly devices) in the future for use in clinical settings in combination with other predictors (if not adequate alone).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the use of cfDNA for predicting dengue severity has not been reported earlier, although there are reports on the prognostic value of cfDNA in other conditions [21, 45, 46]. In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that plasma cfDNA levels could be used as a potential predictor of SD in acute phase of illness. Since the removal of cfDNA from the bloodstream is rapid [21], further prospective studies with a larger sample size should be done to investigate cfDNA kinetics and combined with other early clinical parameters of dengue patients would improve its diagnostic ability for SD.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Diagnostic assay results of the eligible dengue patients (n = 61). Fig. S1. Standard curve plot of Lambda DNA. Fig. S2. cfDNA levels between primary and secondary dengue infection.

Additional file 2. The demographic, laboratory and clinical details of all eligible study participants including their diagnosis and clinical course information.

Authors’ contributions

NTNP, SPD, LNW, VTQH, NTH, KH conceived and designed the study. NTNP, DHM, SPD, LHP, NVT, TTNH, TVA, TMT, LNW, VTQH performed the experiments and collected samples. NTNP, DHM, SPD, SM, MGK, MEM, NTH, KH: analyzed and interpreted the data. SPD, NTNP, NTH, KH wrote the draft. SPD, NTH, KH supervised the work. All authors contributed in writing and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the dengue patients enrolled in this study for their generous participation. This study was conducted (in part) at the Joint Usage/Research Center on Tropical Disease, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional files].

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. All authors consented for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Pasteur Institute in Ho Chi Minh City (PIHCM), Vietnam (No. 602/QD-Pas 27/12/10), and Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan (No. 11063072) and conducted according to Helsinki Declaration with a written informed consent being obtained from each study participant and/or parent/primary caregiver.

Funding

This study was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases (J-GRID) (Grant Number JP18fm0108001 to KH). This work was supported (in part) by a “Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B)” from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan for 2016–2019 (Grant Number 16H05844 to NTH). The funders had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in writing the manuscript and decision to publish.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the ROC

- cfDNA

Cell-free DNA

- CI

Confidence interval

- DENV

Dengue virus

- HMGB

High mobility group box

- IQR

Interquartile range

- NS

Non-structural

- PIHCM

Pasteur Institute in Ho Chi Minh City

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- RT

Reverse transcription

- SD

Severe dengue

- WHO

World Health Organization

Contributor Information

Nguyen Thi Ngoc Phuong, Email: ngocphuong0502@gmail.com.

Dao Huy Manh, Email: daohuymanh@gmail.com.

Shyam Prakash Dumre, Email: sp.dumre@gmail.com.

Shusaku Mizukami, Email: mizukami@nagasaki-u.ac.jp.

Lan Nguyen Weiss, Email: lnweiss@uci.edu.

Nguyen Van Thuong, Email: thuong_nguyen_1981@yahoo.com.vn.

Tran Thi Ngoc Ha, Email: hatran.vn82@yahoo.com.

Le Hong Phuc, Email: dr.phuclehong@gmail.com.

Tran Van An, Email: bsanbt2005@gmail.com.

Thuan Minh Tieu, Email: tieut@mcmaster.ca.

Mohamed Gomaa Kamel, Email: mohamedgomaa@s-mu.edu.eg.

Mostafa Ebraheem Morra, Email: mostafamorra430@gmail.com.

Vu Thi Que Huong, Email: huongpasteur@hotmail.com.

Nguyen Tien Huy, Email: nguyentienhuy@tdtu.edu.vn.

Kenji Hirayama, Email: hiraken@nagasaki-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496(7446):504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control: new edition [http://www.who.int/rpc/guidelines/9789241547871/en/files/189/en.html]. [PubMed]

- 3.Guzman MG, Gubler DJ, Izquierdo A, Martinez E, Halstead SB. Dengue infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16055. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty PR, Puerta-Guardo H, Killingbeck SS, Glasner DR, Hopkins K, Harris E. Dengue virus NS1 triggers endothelial permeability and vascular leak that is prevented by NS1 vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(304):304ra141. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godoi IP, Lemos LL, de Araujo VE, Bonoto BC, Godman B, Guerra AA. CYD-TDV dengue vaccine: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, immunogenicity and safety. J Compar Effect Res. 2017;6(2):165–180. doi: 10.2217/cer-2016-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavailler P, Tarantola A, Leo YS, Lover AA, Rachline A, Duch M, Huy R, Quake AL, Kdan Y, Duong V, et al. Early diagnosis of dengue disease severity in a resource-limited Asian country. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):512. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1849-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macedo GA, Gonin ML, Pone SM, Cruz OG, Nobre FF, Brasil P. Sensitivity and specificity of the World Health Organization dengue classification schemes for severe dengue assessment in children in Rio de Janeiro. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YH, Leong WY, Wilder-Smith A. Markers of dengue severity: a systematic review of cytokines and chemokines. J Gener Virol. 2016;97(12):3103–3119. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soo KM, Khalid B, Ching SM, Tham CL, Basir R, Chee HY. Meta-analysis of biomarkers for severe dengue infections. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3589. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nhi DM, Huy NT, Ohyama K, Kimura D, Lan NT, Uchida L, Thuong NV, Nhon CT, le Phuc H, Mai NT, et al. A proteomic approach identifies candidate early biomarkers to predict severe dengue in children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inokuchi M, Dumre SP, Mizukami S, Tun MMN, Kamel MG, Manh DH, Phuc LH, Van Thuong N, Van An T, Weiss LN, et al. Association between dengue severity and plasma levels of dengue-specific IgE and chymase. Adv Virol. 2018;163(9):2337–2347. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrasco LR, Leo YS, Cook AR, Lee VJ, Thein TL, Go CJ, Lye DC. Predictive tools for severe dengue conforming to World Health Organization 2009 criteria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(7):e2972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen MT, Ho TN, Nguyen VVC, Nguyen TH, Ha MT, Ta VT, Nguyen LDH, Phan L, Han KQ, Duong THK, et al. An evidence-based algorithm for early prognosis of severe dengue in the outpatient setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(5):656–663. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potts JA, Gibbons RV, Rothman AL, Srikiatkhachorn A, Thomas SJ, Supradish P-O, Lemon SC, Libraty DH, Green S, Kalayanarooj S. Prediction of dengue disease severity among pediatric Thai patients using early clinical laboratory indicators. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(8):e769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia P, Radpour R, Zachariah RR, Fan X, Kohler C, Hahn S, Holzgreve W, Zhong X. Simultaneous quantitative assessment of circulating cell-free mitochondrial and nuclear DNA by multiplex real-time PCR. Genet Mol Biol. 2009;32(1):20–24. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009000100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyapati RK, Tamborska A, Dorward DA, Hosh GT. Advances in the understanding of mitochondrial DNA as a pathogenic factor in inflammatory diseases. F1000 Res. 2017;6:169. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10397.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Vaart M, Pretorius PJ. Circulating. DNA Its origin and fluctuation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1137:18–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1448.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanetti-Dallenbach R, Wight E, Fan AX, Lapaire O, Hahn S, Holzgreve W, Zhong XY. Positive correlation of cell-free DNA in plasma/serum in patients with malignant and benign breast disease. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(2a):921–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto Y, Uemura M, Nakano K, Hayashi Y, Wang C, Ishizuya Y, Kinouchi T, Hayashi T, Matsuzaki K, Jingushi K, et al. Increased level and fragmentation of plasma circulating cell-free DNA are diagnostic and prognostic markers for renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20467–20475. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler C, Barekati Z, Radpour R, Zhong XY. Cell-free DNA in the circulation as a potential cancer biomarker. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(8):2623–2628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvi S, Gurioli G, De Giorgi U, Conteduca V, Tedaldi G, Calistri D, Casadio V. Cell-free DNA as a diagnostic marker for cancer: current insights. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6549–6559. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S100901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limonta D, Capo V, Torres G, Perez AB, Guzman MG. Apoptosis in tissues from fatal dengue shock syndrome. J Clin Virol. 2007;40(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiyen Y, Masrinoul P, Kalayanarooj S, Pulmanausahakul R, Ubol S. Characteristics of dengue virus-infected peripheral blood mononuclear cell death that correlates with the severity of illness. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53(8):442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha TT, Huy NT, Murao LA, Lan NT, Thuy TT, Tuan HM, Nga CT, Tuong VV, Dat TV, Kikuchi M, et al. Elevated levels of cell-free circulating DNA in patients with acute dengue virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e25969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(supp_2):S89–S95. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Innis BL, Nisalak A, Nimmannitya S, Kusalerdchariya S, Chongswasdi V, Suntayakorn S, Puttisri P, Hoke CH. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to characterize dengue infections where dengue and Japanese encephalitis co-circulate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40(4):418–427. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanciotti RS, Calisher CH, Gubler DJ, Chang GJ, Vorndam AV. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(3):545–551. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.545-551.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermann LL, Thaisomboonsuk B, Poolpanichupatam Y, Jarman RG, Kalayanarooj S, Nisalak A, Yoon I-K, Fernandez S. Evaluation of a dengue NS1 antigen detection assay sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of acute dengue virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(10):e3193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan NTP, Kikuchi M, Huong VTQ, Ha DQ, Thuy TT, Tham VD, Tuan HM, Tuong VV, Nga CTP, Van Dat T, et al. Protective and enhancing HLA alleles, HLA-DRB1*0901 and HLA-A*24, for severe forms of dengue virus infection, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(10):e304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szpechcinski A, Struniawska R, Zaleska J, Chabowski M, Orlowski T, Roszkowski K, Chorostowska-Wynimko J. Evaluation of fluorescence-based methods for total vs amplifiable DNA quantification in plasma of lung cancer patients. J Physiol Pharm. 2008;59(Suppl 6):675–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramachandran K, Speer CG, Fiddy S, Reis IM, Singal R. Free circulating DNA as a biomarker of prostate cancer: comparison of quantitation methods. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(10):4521–4529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher SR. Quantitation of DNA and RNA with Absorption and Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Curr Prot Immunol. 2017;116:A 3L 1–A 3L 4. doi: 10.1002/cpim.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narvaez F, Gutierrez G, Perez MA. Evaluation of the traditional and revised WHO classifications of dengue disease severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nm J. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1315–1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furuta T, Murao LA, Lan NTP, Huy NT, Huong VTQ, Thuy TT, Tham VD, Nga CTP, Ha TTN, Ohmoto Y, et al. Association of mast cell-derived vegf and proteases in dengue shock syndrome. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(2):e1505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tissera H, Rathore APS, Leong WY, Pike BL, Warkentien TE, Farouk FS, Syenina A, Eong Ooi E, Gubler DJ, Wilder-Smith A, et al. Chymase level is a predictive biomarker of dengue hemorrhagic fever in pediatric and adult patients. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(9):1112–1121. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phakhounthong K, Chaovalit P, Jittamala P, Blacksell SD, Carter MJ, Turner P, Chheng K, Sona S, Kumar V, Day NPJ, et al. Predicting the severity of dengue fever in children on admission based on clinical features and laboratory indicators: application of classification tree analysis. BMC Pediatrics. 2018;18(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira ERA, Povoa TF, Nuovo GJ, Allonso D, Salomao NG, Basilio-de-Oliveira CA, Geraldo LHM, Fonseca CG, Lima FRS, Mohana-Borges R, et al. Dengue fatal cases present virus-specific HMGB1 response in peripheral organs. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16011. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aqarwal REE, Chaturvedi UC, Nagar R, Mustafa AS. Profile of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in patients with dengue haemorrhagic fever. Int J Exp Pathol. 1999;80:143–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1999.00107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvalho DM, Garcia FG, Terra AP, Lopes Tosta AC, Silva Lde A, Castellano LR, Silva Teixeira DN. Elevated dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 serum levels and altered toll-like receptor 4 expression, nitric oxide, and tumor necrosis factor alpha production in dengue hemorrhagic Fever patients. J Trop Med. 2014;2014:901276. doi: 10.1155/2014/901276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ojha A, Nandi D, Batra H, Singhal R, Annarapu GK, Bhattacharyya S, Seth T, Dar L, Medigeshi GR, Vrati S, et al. Platelet activation determines the severity of thrombocytopenia in dengue infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41697. doi: 10.1038/srep41697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon AY, Sutherland MR, Pryzdial ELG. Dengue virus binding and replication by platelets. Blood. 2015;126(3):378–385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-598029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boudreau LH, Duchez A-C, Cloutier N, Soulet D, Martin N, Bollinger J, Paré A, Rousseau M, Naika GS, Lévesque T, et al. Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA-secreted phospholipase A < sub > 2</sub > to promote inflammation. Blood. 2014;124(14):2173–2183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-573543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin C, Gu J, Hu J, Qian H, Fei X, Li Y, Liu R, Meng W. Platelets activation is associated with elevated plasma mitochondrial DNA during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothor Surg. 2016;11:90. doi: 10.1186/s13019-016-0481-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dennis Lo YM, Rainer TH, Chan LYS, Hjelm NM, Cocks RA. Plasma DNA as a prognostic marker in trauma patients. Clin Chem. 2000;46(3):319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rainer TH, Wong HR, Lam W, Yuen E, Lam NYL, Metreweli C, Dennis Lo YM. Prognostic use of circulating plasma nucleic acid concentrations in patients with acute stroke. Clin Chem. 2003;49(4):562–569. doi: 10.1373/49.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Diagnostic assay results of the eligible dengue patients (n = 61). Fig. S1. Standard curve plot of Lambda DNA. Fig. S2. cfDNA levels between primary and secondary dengue infection.

Additional file 2. The demographic, laboratory and clinical details of all eligible study participants including their diagnosis and clinical course information.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional files].