Abstract

Purpose:

The United States is typically viewed as a wealthy country, yet not all households have access to enough food for an active, healthy life. The purpose of this investigation was to validate a 2-item written food security screen that health providers may use to identify food insecurity in their patient populations.

Methods:

Data were obtained from 150 parents or guardians who brought a child to a dental appointment at The Center for Pediatric Dentistry, a university-affiliated dental clinic in Seattle, WA. The sensitivity and the specificity of two written questions were determined by comparison with the United States Department of Agriculture Six-item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module.

Results:

The sample consisted of 141 surveys after those with critical questions left blank were removed. The prevalence of food insecurity was found to be 31% at the Center for Pediatric Dentistry. The 6-item screen identified 44 food-insecure families with an affirmative response to two or more questions. Compared with the 6-item screen, the 2-item screen was found to have 95.4% sensitivity and 83.5% specificity.

Conclusions:

The 2-item food security screen was found to be sensitive and reasonably specific, providing a quick and accurate method to identify food-insecure families.

Keywords: Food insecurity, validation studies, dentistry, Six-Item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module

Introduction

In 2016, 12.3% of all US households were categorized as food-insecure, meaning they lacked adequate financial resources for food.1 Food insecurity is defined as “Limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire foods in socially acceptable ways”.2 The percentage of US households with food insecurity has been decreasing since hitting a high of 14.9% in 2011, however this percentage is still higher than the 11.1% food insecurity in the US prior to the Great Recession.1 In adults, food insecurity has been associated with stress, depression, and poor oral health.3 Food insecurity is a risk factor for developmental delays in growth, cognitive function, and overall health in children.4 An analysis of 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data observed an association between food insecurity and untreated dental caries in children.5 Similarly, a cross-sectional study in the Brazilian Amazon found that food insecurity is associated with dental caries in 7 to 9 year old children.6 Even though their finances are limited, many families with food insecurity do bring their children to dental appointments. A 2011–2012 study found that 30% of households with a child attending dental appointments at a university-affiliated dental clinic were food-insecure.7 A separate study in 2009 found that 52% of households with a child attending dental appointments at a children’s hospital-affiliated dental clinic were food-insecure.8

The American Dental Association has patient recommendation guidelines that suggest limiting snacks between meals, choosing nutritious foods when snacking, and avoiding frequent consumption of sugary beverages and junk food.9 Unfortunately, when food energy density is compared to food costs, foods high in sugars, sweets, fats, and oils have the highest mean energy density and are some of the least expensive food choices for meeting energy needs.10 For example, fresh fruits and vegetables are among the most expensive foods and they provide the least mean energy density.10 Therefore, many low-income families may maximize energy and minimize food costs by choosing foods high in sugar and fat.

In 2016, only 59% of food-insecure households participated in one of the three major federal food assistance programs; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), or the National School Lunch Program.1 Dental visits provide an opportunity not only to educate patients and families about nutrition and its link to oral health, but also to refer families to food and nutrition assistance programs that can provide them with resources for a nutritious diet. Considering a family’s food security status is thus a key element to comprehensive care that should be provided by a dentist (see da Fonseca11). However, in order to provide counseling and referral to federal, state and local food and nutrition assistance programs, dentists need to assess food security in their patients’ households. This creates a need for a quick and effective method to evaluate a household’s food security status.

Multiple food security screening tools have been used for research purposes. An 18-item interview that was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to monitor state and national food security rates is considered the gold standard in the United States.2 A shorter, 6-item written screen has been shown to have excellent sensitivity and good specificity by comparison, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Six-Item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module.12 In a 2010 study by Hager and colleagues, two questions from the 18-item interview were found to correctly identify 97% of food-insecure households (sensitivity, correcting detecting a true positive) and 83% of food-secure households (specificity, correctly rejecting a true negative).13 The Hager study employed face-to-face interviews of caregivers in a hospital-based setting between 1998 and 2005. If validated, a written version of this screener could readily be incorporated into health history forms for use in dental offices. The purpose of the current study was to assess the validity of a written version of the 2-item food-security screen identified by Hager and colleagues. The 2-item screen was tested for sensitivity and specificity compared with the previously validated 6-item written screen. As a validity check, the ability of the 2-item screen to detect the same trend of a higher frequency of food insecurity in households headed by a single female that is consistently found in national surveys was also assessed.1

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample of parents or guardians who brought a child to a dental appointment at The Center for Pediatric Dentistry, a university-affiliated dental clinic in Seattle, WA, on one of ten days in August of 2012 were enrolled in the study. Research staff members set up a table in the waiting room of the clinic on each of the ten days. Information about the study was available at the table. Front desk staff in the clinic also provided an informational flyer about the study when the parent or guardian checked in for the child’s appointment. The study was described in the flyer as a survey of “Family Food & Health”. Those interested in participating in the study were given a questionnaire to complete once written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian. Families were excluded from participation if the adult accompanying the child to the appointment was unable to speak English or did not provide informed consent. Families were provided with a small gift (water bottle and sticker) for participating in the study. Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division, Seattle, Washington.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was distributed and completed with paper and pencil and consisted of 32 questions. The main questions of interest were seven questions related to food insecurity. Two of these items were adapted from Hager and colleagues13 and formed the 2-item screen being assessed. This screen consisted of the following two questions: 1) “We worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more” and 2) “The food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.” Respondents were prompted to endorse these items as “Often True,” “Sometimes True,” “Never True” in the last 12 months or “Don’t Know”. Question two also forms part of the 6-item food security screen and was not asked a second time. The remaining five items of the 6-item screen were also included in the questionnaire.

Additional questions (eight) gathered information on household residents, including the number of adults over 18, the number of children and their ages, smoking status of household members, self-reported general and oral health of the adult completing the questionnaire, and the adult’s report of the general and oral health of the child attending the dental appointment. Seven questions inquired about children with special healthcare needs in the household. These included the five items of the Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative’s Children with Special Healthcare Needs Screener along with two additional questions clarifying cause and duration.14 Four questions were asked about commonly used assistance programs. These were the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), the Supplemental Nutrition and Food Assistance Program (SNAP), the National School Lunch Program, and the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) Medicaid program. Finally, seven questions collected demographic information such as race, ethnicity, level of education, gender, age, relationship to the patient, and the primary language spoken in the home.

Statistical Analyses

For any of the seven questions pertaining to food insecurity, having responses of “Often True” or “Sometimes True” were considered an affirmative response. For the 2-item screen, an affirmative response on either item was considered to be positive for food insecurity. For the Six-Item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module, two or more affirmative responses were considered positive for food insecurity, consistent with scoring guidelines.2

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables of interest stratified by food security status via the 6-item screen. Chi-square tests of association and Fisher’s Exact tests were used to determine associations between the variables of interest and food security status via the 6-item screen.

Sensitivity was calculated as the number of food-insecure households identified by both the 2-item screen and the 6-item screen, divided by the total number of food-insecure households identified by the 6-item screen. Specificity was calculated as the number of food-secure households identified by both the 2-item screen and the 6-item screen, divided by the total number of food-secure households identified by the 6-item screen.

Participants were excluded from the analysis if they did not answer one or more of the seven questions needed to determine food security status. All analyses were performed using Stata Version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 150 surveys were collected, of which 141 (94%) were eligible for analysis. Adults completing the survey were 82% female and 18% male. Sixty-three percent indicated they were White, 11% Asian, 21% indicated other or multiple races, and 5% did not report race. Sixty-six percent indicated enrollment in DSHS Medicaid. The characteristics of the study population by the 6-item food security status are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Caregiver Demographic Characteristics by 6-item Food Security Status.

| Food Insecure N = 44 |

Food Secure N = 97 |

Total N = 141 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Caregiver Relationship | |||

| Mother | 38 (86.4%) | 77 (79.4%) | 115 (81.6%) |

| Father | 5 (11.3%) | 17 (17.5%) | 22 (15.6%) |

| Other | 1 (2.3%) | 3 (3.1%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| Caregiver Gender | |||

| Male | 6 (13.6%) | 20 (20.6%) | 26 (18.4%) |

| Female | 38 (86.4%) | 77 (79.4%) | 115 (81.6%) |

| Caregiver Age | |||

| < 30 | 5 (11.4%) | 13 (13.4%) | 18 (12.8%) |

| 30–39 | 22 (50.0%) | 41 (42.3%) | 63 (44.7%) |

| 40–49 | 13 (29.5%) | 32 (33.0%) | 45 (31.9%) |

| ≥ 50 | 3 (6.8%) | 11 (11.3%) | 14 (9.9%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.3%) | 0 | 1 (0.7%) |

| Caregiver Race | |||

| White | 29 (65.9%) | 60 (61.8%) | 89 (63.1%) |

| Asian | 1 (2.3%) | 15 (15.5%) | 16 (11.3%) |

| Other/Multiple | 11 (25.0%) | 18 (18.6%) | 29 (20.6%) |

| Missing | 3 (6.8%) | 4 (4.1%) | 7 (5.0%) |

| Caregiver Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 5 (11.4%) | 16 (16.5%) | 21 (14.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 38 (86.3%) | 78 (80.4%) | 116 (82.3%) |

| Missing | 1 (2.3%) | 3 (3.1%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| Caregiver Education | |||

| High school or less | 13 (29.5%) | 16 (16.5%) | 29 (20.6%) |

| College | 23 (52.3%) | 60 (61.8%) | 83 (58.9%) |

| Graduate School | 5 (11.4%) | 19 (19.6%) | 24 (17.0%) |

| Missing | 3 (6.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | 5 (5.5%) |

| Number of Adults in Household | |||

| 1 | 20 (45.4%) | 25 (25.8%) | 45 (31.9%) |

| 2 or more | 24 (54.6%) | 71 (73.2%) | 95 (67.4%) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Number of Children in Household | |||

| 1–2 | 10 (22.7%) | 23 (23.7%) | 33 (23.4%) |

| 3 | 20 (45.5%) | 43 (44.3%) | 63 (44.7%) |

| 4 | 8 (18.2%) | 17 (17.5%) | 25 (17.7%) |

| 5 or more | 6 (13.6%) | 14 (14.4%) | 20 (14.2%) |

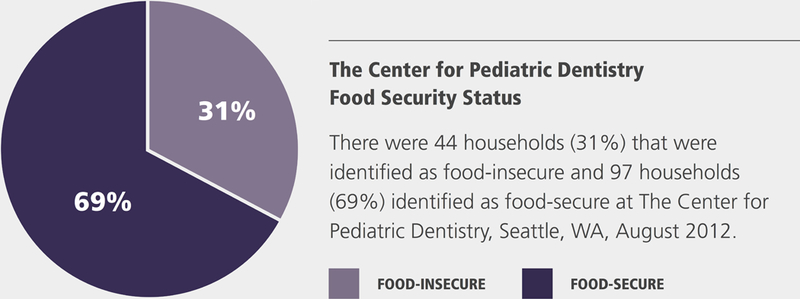

The 6-item screen identified 44 food-insecure families (31.2% of eligible questionnaires) (see Figure 1). Of these, 42 of the families were also identified as food-insecure by the 2-item screen, indicating a sensitivity of 95.4% for the 2-item screen. Of the 97 families identified as food-secure by the 6-item screen, 81 families were also classified as food-secure by the 2-item screen, indicating a specificity of 83.5%. Cross tabulation of the 2-item screen by the 6-item screen is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Food security status of 141 households surveyed in the waiting area of the Center for Pediatric Dentistry in August of 2012 is depicted in the pie chart of Figure 1. Food-secure households are depicted in dark purple, while food-insecure households are depicted in lavender. A household was identified as food-insecure if the parent or guardian completing the survey gave two or more affirmative responses on the 6-item short form of the Household Food Security Scale.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity of the 2-Item Food Security Screen.

| 6-Item Screen | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Item Screen | Food Insecure | Food Secure | Total |

| Food Insecure | 42 | 16 | 58 |

| Food Secure | 2 | 81 | 83 |

| Total | 44 | 97 | 141 |

Sensitivity: 42/44 = 95.4%

Specificity: 81/97 = 83.5%

A greater frequency of food insecurity was detected in households headed by a single female than all other households using either the 6-item screen (χ2(1) = 4.7, p = 0.03) or the 2-item screen (χ2(1) = 9.3, p = 0.002) (see Table 3). A greater frequency of food insecurity, as measured by the 6-item screen, was detected in households currently enrolled in DSHS Medicaid (88.6% Food Insecure households vs. 55.7% Food Secure households, χ2(1) = 14.0, p < 0.001), SNAP (61.3% Food Insecure households vs. 24.7% of Food Secure households, χ2(1) = 17.5, p < 0.001), and the National School Lunch Program (70.4% of Food Insecure households vs. 29.9% of Food Secure households, χ2(1) = 20.0, p < 0.001).

Table 3:

Food Insecurity by Single Female Households.

| Single Female Households | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| 6-Item Screen | |||

| Food Insecure | 19 (43.2%) | 25 (56.8%) | 44 (100%) |

| Food Secure | 24 (25.0%) | 72 (75.0%) | 96 (100%) |

| 2-Item Screen | |||

| Food Insecure | 26 (44.8%) | 32 (55.2%) | 58 (100%) |

| Food Secure | 17 (20.7%) | 65 (79.3%) | 82 (100%) |

| Total | 43 (30.7%) | 97 (69.3%) | 140 |

Discussion

The prevalence of food insecurity at this university-affiliated dental clinic was 31.2%, exceeding the 2012 national average of 14.51% for all US households.15 A prior study of families with children attending dental appointments at a hospital-affiliated dental clinic in Seattle found even higher levels of food insecurity – 52% of that population.8 Food insecurity is thus prevalent among families attending dental appointments in community clinics, demonstrating the need for dentists working in such clinics to adjust their dietary recommendations to account for food costs and availability to the families they serve.

The 2-item food security screen was found to be sensitive and reasonably specific, providing a quick and accurate method to identify food-insecure families. A sensitivity of 95.4% indicates that only 4.6% of households that have experienced food insecurity were missed. Specificity was reasonable at 83.5%. Some families were possibly misclassified as food-insecure, however, they indicated some degree of concern about food cost and would likely benefit from additional counseling. Attesting to the validity of the 2-item screen, households headed by a single female were found to have a higher frequency of food insecurity than other households. This is consistent with national findings and the findings using the 6-item screen in the same sample.1

It should be acknowledged, however, that this study may be overestimating the sensitivity of the 2-item measure by using the 6-item survey as the comparison measure rather than the 18-item interview, which is considered the gold standard. Compared with the 18-item survey, the 6-item screen has been found to have 92% sensitivity and 99.4% specificity in determining overall food insecurity in a general population, and 85.6% sensitivity and 99.5% specificity in a population of households with children.12 This indicates that, while our specificity results are likely very similar to what we would have found compared with the 18-item survey, the sensitivity results are likely somewhat inflated. Dentists utilizing the 2-item scale may thus risk missing some families with food insecurity.

Given that the Center for Pediatric Dentistry is a university-affiliated clinic serving a wide variety of patients, the sample collected was diverse. The population surveyed included those with both high and low levels of education, as well as a broad range of socioeconomic statuses. The diversity of the sample provided the variability needed to properly assess the sensitivity, specificity, and validity of the two-item screen -- with adequate numbers of both low and high food security families. It is likely that food insecurity would be identified less frequently in private practice and more frequently identified in community clinics. Despite the demographic diversity of the sample, we acknowledge that there were limitations in the sampling procedure. All participants were recruited on one of just ten different days in August of 2012. Although all families checking in on those appointment days were informed of the study, families with particular interest in food issues may have been more likely to respond to a request to participate. This could have led to a higher prevalence estimate for food insecurity. It is also conceivable that families coming to the clinic in August differ systematically from those coming at other times of the year. For example, those with school-age children may be more likely to make an appointment in August than those with pre-school children. Our sample may thus not be representative of those families seen in the dental clinic at other times of the year.

Families are open to being asked about food security in a clinical setting.16 Parents in households at risk for food insecurity may be referred to organizations that can assist them with additional financial, health, food and nutrition resources. Food and nutrition assistance programs improve food security, but they may not be sufficient to completely eliminate food insecurity, since some families on those programs continue to experience food insecurity.17 Nevertheless, family food security may be maximized by referral to all appropriate resources.

Food insecurity should be considered a risk factor for increased oral disease. It has been associated with dental related pain, chewing difficulties, embarrassment of the appearance or health of teeth, and adversely affected speech, sleep or work due to poor oral health.3 Persons identified as food-insecure compared to those that are food-secure, are more likely to wear dentures and are two times more likely to have reported a toothache in the last month.3 Food insecurity was found to be the underlying cause of increased incidence of tooth extraction in children from New Zealand.18 Therefore it would be logical to include food security questions as part of a caries risk assessment.

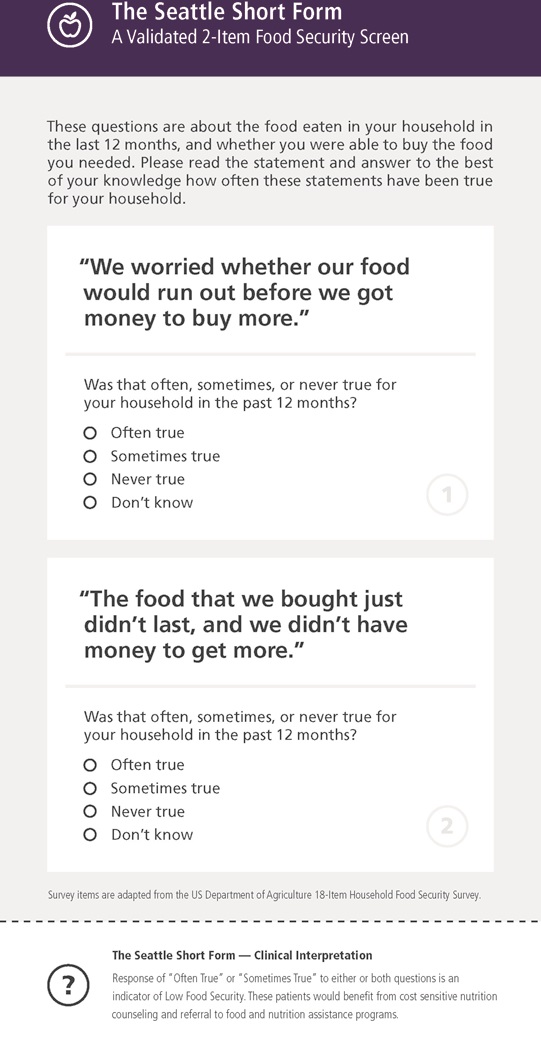

This study indicates that the high sensitivity of the 2-item screen would make it a good tool for clinicians to use to identify families in need and to personalize their counseling and treatment as required. At only two items, this screen is also short enough to be readily incorporated into a standard health history form so that it may be completed for all patients. Alternatively, the screen could be readily administered as a brief survey completed by parents at community health fairs or in the waiting room at a dental office (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An example of how the 2-item food security screening tool could be formatted for use in the dental setting is shown in Figure 2. The two questions employed in the screening tool are based on the US Department of Agriculture Guide to Measuring Household Food Security11 with further adaptations by Blumberg et al.12 and Hager et al.

Conclusion

The 2-item food security screen is a valid measure of household food insecurity.

The 2-item food security screen is sensitive and specific when compared with the standard 6-item survey.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Quinn Ianniciello for his time and talent in developing the visual graphics used in this study. This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR00025016. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Washington Dental Service Endowed Professorship.

Contributor Information

Nick E. Radandt, Dentist, Dental Care Seattle, 600 Broadway, Suite 330, Seattle, WA 98122, Phone: 206-325-0166, Fax: 206-322-9345, nickradandt@icloud.com.

Tara Corbridge, Graduate Student, Health Services, Box 353410, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-3410, Phone: 206-685-1068, tara.ashleman@gmail.com.

Donna B. Johnson, Professor Emeritus, Health Services, Box 353410, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-3410, Phone: 206-685-1068, Fax: 206-685-1696, djohn@uw.edu.

Amy S. Kim, Clinical Associate Professor, Pediatric Dentistry, Box 354915, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-4915, Phone: 206-543-0407, akim3@uw.edu.

JoAnna M. Scott, Assistant Professor, Research & Graduate Programs, School of Dentistry, Room 3130, University of Missouri Kansas City, 650 E. 25th St, Kansas City, MO 64108, Phone: 816-235-2066, Fax: 206-616-2612, scottjoa@umkc.edu.

Susan E. Coldwell, Professor, Oral Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, Box 357475, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7475, Phone: 206-616-3087, Fax: 206-616-2612, scoldwel@uw.edu.

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016, US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service; 2017. Economic Research Report number 237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security: Revised 2000. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000; Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/FSGuide.pdf 2012–11–12 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6FcFuuMSd). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muirhead V, Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2009; 37: 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook JT, Frank DA. Food security, poverty, and human development in the United States. Ann NY Acad Sci 2008; 1136: 193–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi DL, Masterson EE, Carle AC, Mancl LA, Coldwell SE. Socioeconomic status, food security, and dental caries in US Children: mediation analyses of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008–2008. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: 860–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benicio FP, Narvai PC, Cardosa MA. Food insecurity and dental caries in schoolchildren: a cross-sectional survey in the western Brazilian Amazon. Eur J Oral Sci 2014; 122: 210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi DL, Dinh MA, da Fonseca MA, Scott JM, Carle AC. An exploratory cross-sectional analysis of socioeconomic status, food insecurity, and fast food consumption: implications for dietary research to reduce children’s oral health disparities. J Acad Nutr Diet 2015; 115: 1599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatzopoulos S, Johnson D, Delecki D, Liu L, Garcia M, Coldwell SE. Prevalence of Food Insecurity in a US Community Dental Clinic. World Congress on Preventive Dentistry; September 2009; Phuket, Thailand Available at: “https://iadr.abstractarchives.com/abstract/wcpd2009–124266/prevalence-of-food-insecurity-in-a-us-community-dental-clinic”. 2018–03–21 (Archived by WebCite® at “http://www.webcitation.org/6y64ncnQb”). [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Dental Association. Diet and Tooth Decay. JADA 2002;133:527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drewnowski A The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutri 2010; 92(5): 1181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Fonseca MA. Eat or heat? The effects of poverty on children’s behavior. Pediatr Dent 2014; 36: 132–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. Am J Public Health 1999;89(8):1231–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and Validity of a 2-Item Screen to Identify Families at Risk for Food Insecurity. Pediatrics 2010; 126(1): e26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Children with Special Healthcare Needs (CSHCN) Screener. Available at: “http://www.cahmi.org/projects/children-with-special-health-care-needs-screener/”. 2018–07–22 (Archived by WebCite® at “http://www.webcitation.org/717Cc3hEA”)

- 15.USDA Economic Research Service data. Available at: “https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics/#trends”. 2018–03–21 (Archived by WebCite® at “http://www.webcitation.org/6y5jtOJUy”)

- 16.Lawton E, Leiter K, Todd J, Smith L. Welfare reform: advocacy and intervention in the health care setting. Public Health Rep 1999; 114(6): 540–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabli J, Worthington J. Supplemental Nutrtion Assistance Program participation and child food security. Pediatrics 2014; 133: 610–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamieson LM, Koopu Pl. Factors associated with restoration and extraction receipt among New Zealand children. Community Dent Health 2008; 25(1):59–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]