Abstract

Background

The emergence of drug-resistant bacteria is a major hurdle for effective treatment of infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and ESKAPE pathogens. In comparison with conventional drug discovery, drug repurposing offers an effective yet rapid approach to identifying novel antibiotics.

Methods

Ethyl bromopyruvate was evaluated for its ability to inhibit M. tuberculosis and ESKAPE pathogens using growth inhibition assays. The selectivity index of ethyl bromopyruvate was determined, followed by time–kill kinetics against M. tuberculosis and Staphylococcus aureus. We first tested its ability to synergize with approved drugs and then tested its ability to decimate bacterial biofilm. Intracellular killing of M. tuberculosis was determined and in vivo potential was determined in a neutropenic murine model of S. aureus infection.

Results

We identified ethyl bromopyruvate as an equipotent broad-spectrum antibacterial agent targeting drug-susceptible and -resistant M. tuberculosis and ESKAPE pathogens. Ethyl bromopyruvate exhibited concentration-dependent bactericidal activity. In M. tuberculosis, ethyl bromopyruvate inhibited GAPDH with a concomitant reduction in ATP levels and transferrin-mediated iron uptake. Apart from GAPDH, this compound inhibited pyruvate kinase, isocitrate lyase and malate synthase to varying extents. Ethyl bromopyruvate did not negatively interact with any drug and significantly reduced biofilm at a 64-fold lower concentration than vancomycin. When tested in an S. aureus neutropenic thigh infection model, ethyl bromopyruvate exhibited efficacy equal to that of vancomycin in reducing bacterial counts in thigh, and at 1/25th of the dosage.

Conclusions

Ethyl bromopyruvate exhibits all the characteristics required to be positioned as a potential broad-spectrum antibacterial agent.

Introduction

Drug-resistant bacterial pathogens continue to escalate worldwide and present a significant threat to healthcare systems. Owing to limited treatment options, elimination of acute and chronic infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and ESKAPE pathogens is being severely compromised, leading to ballooning healthcare costs as well as concomitant increases in morbidity and mortality. TB remains a pathogen of significant global interest, especially with the burgeoning number of MDR as well as XDR cases, which are resistant to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. Similarly, ESKAPE pathogens are responsible for increasing incidences of difficult-to-treat community and hospital-acquired infections, which has led to renewed efforts in novel drug discovery. Thus, the discovery of novel agents effective against drug-resistant pathogens that are capable of evading resistance mechanisms is the unmet need of the hour. As conventional drug discovery has been unable to fill this void, drug repurposing offers an alternative route to expediting the development of potential scaffolds and targets in the drug development pipeline.1,2

In the present study, we evaluated the antibacterial potential of ethyl bromopyruvate (EBP), a derivative of 3-bromo-pyruvic acid (3-BPA), an anticancer agent that inhibits the Warburg effect, for which an antibiotic effect has been proposed but not investigated.3 Here, we report a detailed biological analysis of EBP, including in vivo efficacy in a murine neutropenic thigh infection model against Staphylococcus aureus. We believe that it represents a novel scaffold with potential to be deployed against S. aureus infections.

Materials and methods

Growth media and reagents

All bacterial media and supplements, including Middlebrook 7H9 broth, 7H11 agar, ADC (albumin, dextrose and catalase), OADC, CAMHB, Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) and tryptic soya broth (TSB), were purchased from Becton-Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). All the other chemicals and antibiotics were procured from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). DMEM and FBS were purchased from Lonza, USA.

Bacterial cultures

Mtb H37Ra, Mtb H37Rv ATCC 27294, isoniazid-resistant Mtb ATCC 35822, rifampicin-resistant Mtb ATCC 35838, streptomycin-resistant Mtb ATCC 35820 and ethambutol-resistant Mtb ATCC 35837 were propagated in 7H9 broth supplemented with glycerol, ADC and 0.05% Tween-80 at 37°C.

In order to determine the antimicrobial specificity of EBP, antibacterial activity was evaluated against a panel of ESKAPE pathogens consisting of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213, Klebsiella pneumoniae BAA-1705, Acinetobacter baumannii BAA-1605 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853. CAMHB was used for propagation of these bacteria at 37°C. All bacterial strains were procured from ATCC (Manassas, USA).

Antibacterial susceptibility testing

Antibacterial susceptibility testing was carried out utilizing a broth microdilution assay according to CLSI guidelines.4 Stock solutions (10 mg/mL) of EBP and controls were prepared in DMSO and stored at −20°C. Bacterial cultures were inoculated in appropriate media; OD600 of cultures was measured, and cultures were then diluted to achieve ∼106 cfu/mL. EBP and control drugs were tested at concentrations of 0.5–64 mg/L; 2-fold serial dilutions were prepared, with 2.5 μL of each dilution added per well of a 96-well round-bottom microtitre plate. Subsequently, 97.5 μL of ∼106 cfu/mL bacterial suspension was added to each well along with appropriate controls. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days for Mtb and 18–24 h for ESKAPE pathogens. The MIC was defined as the lowest compound concentration at which there was no visible growth. All MIC determinations were carried out three times independently in duplicate.

Cytotoxicity determination of EBP using BMDM cells

The cytotoxicity of EBP was determined against BMDM cells as reported previously.5 Briefly, bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and stimulated for 7 days with 10% conditioned medium derived from L929 cultures.6 Cells were harvested and 5 × 104 cells/well were seeded in a 96-well plate. After 24 h of incubation, cells were treated for 48 h with different concentrations of EBP along with appropriate controls. After incubation, 0.01 mL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL stock) was added to each well, cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C and lysis solution was added (0.08 mL/well) to dissolve formazan crystals. Absorbance was read at 570 nm.

Bacterial time–kill kinetics with EBP

EBP’s bactericidal activity was assessed by the time–kill method.7 Briefly, Mtb H37Rv ATCC 27294 was diluted to ∼106 cfu/mL, cells were treated with EBP and appropriate controls at 1× and 10× MIC, then incubated at 37°C for 7 days. A 0.1 mL sample was removed at various timepoints, serially 10-fold diluted in 0.9 mL of PBS and 0.1 mL of the respective dilution was spread on an 7H11 agar plate supplemented with OADC. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 3–4 weeks and colonies were enumerated. Kill curves were constructed by counting the colonies from plates and plotting the cfu/mL of surviving bacteria at each timepoint in the presence and absence of compound.

S. aureus ATCC 29213 was diluted to ∼106 cfu/mL in CAMHB, treated with 1× and 10× MIC of EBP and vancomycin and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 24 h. Samples of 0.1 mL were collected at the time intervals of 0, 1, 6 and 24 h, serially diluted in PBS and plated on MHA followed by incubation at 37°C for 18–20 h. Kill curves were constructed as above. Each experiment was performed three times in duplicate and the data are plotted as means.

EBP’s synergy with approved drugs

Determination of interaction with approved drugs was tested by the chequerboard method. Serial 2-fold dilutions of each drug were freshly prepared prior to testing. EBP was diluted 2-fold along the ordinate while the antibiotics were serially diluted along the abscissa in a 96-well microtitre plate. To each well, 95 μL of ∼105 cfu/mL was added and plates were incubated at 37°C. After incubation, the fractional inhibitory concentrations (FICs) were calculated as follows: ΣFIC = FICA + FICB, where FICA is the MIC of drug A in the combination/MIC of drug A alone and FICB is the MIC of drug B in the combination/MIC of drug B alone. The combination is considered synergistic when the ∑FIC is ≤0.5, indifferent when the ∑FIC is >0.5–4 and antagonistic when the ∑FIC is >4.8

Estimation of intracellular ATP levels upon treatment with EBP

A 10-day-old culture of Mtb H37Ra was diluted to OD600 0.05 and then incubated with 32 mg/L EBP or with plain medium. After 24 h, OD600 was measured and 107 bacteria/0.05 mL medium was transferred into a white, clear-bottom, 96-well microplate (BD, USA). Bactiter-Glo™ reagent (Promega, USA) (25 μL) was added to each well, followed by mixing and incubation for 5 min. Relative luminescence units (RLU) were measured using a Synergy H1 hybrid reader (BioTek, USA) at an integration time of 1 s/well. RLU values were subtracted from the background control of medium with bacteria and data were plotted as a bar graph of RLU/107 cells ± SD, n = 3.

Inhibition of recombinant Mtb GAPDH

Recombinant GAPDH (rGAPDH) was purified from Mtb H37Ra as described previously.9 The purified enzyme was dialysed against 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl and enzyme activity of rGAPDH was assayed. Briefly, 500 ng of purified enzyme was added to 100 μL of assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, 10 mM sodium arsenate and 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.5), 1 mM NAD+ and 2 mM glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P; Sigma–Aldrich) at 25°C. Inhibition was assessed by incubating rGAPDH with different concentrations of EBP (0–8 μM) at 25°C for 5 min. Enzyme activity was measured as the increase in absorbance at 340 nm for 5 min due to formation of NADH. The enzymatic activity without EBP was considered as 100% and percentage residual activity was calculated. Experiments were performed three times independently, each assay reaction was set up in duplicate and data were plotted as percentage residual activity ± SD versus EBP concentration.

Determination of inhibition constant (Ki) for Mtb GAPDH-EBP

Briefly, 400 ng of protein was incubated with 10 nM to 4 μM EBP in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.5), 10 mM sodium arsenate and 5 mM EDTA for times ranging from 15 s to 5 min at 25°C. Reactions were initiated with 1:1 combinations (50 μL each) of enzyme/EBP mix and 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.5, 10 mM sodium arsenate, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM NAD+ and 4 mM G3P. Assays were monitored for 2 min at 25°C. Kinetic constants were calculated as described by Kitz and Wilson.10 The inhibition was calculated by determining the rates of time-matched samples exposed to varying concentrations of EBP. The results were plotted on a logarithmic scale versus time and the slopes were determined by linear regression. The values of the slopes represent the half-life of inactivation (kinactivation). A Kitz–Wilson plot was produced using the half-lives as the y-axis and the reciprocal of the inhibitor concentration as the x-axis.11 Values for Ki and kinactivation were determined from the negative reciprocal of the x-intercept and reciprocal of the y-intercept, respectively.

Estimation of cellular iron levels and transferrin iron uptake in EBP-treated Mtb

Mtb H37Ra cells were cultured to log phase; ∼2 × 108 cells were used in each assay and incubated with 32 mg/L EBP or with plain medium (as control). After 24 h, cultures were spun down to pellets and lysates were prepared in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and protease inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration was estimated by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. The iron concentration per 50 μg of protein lysate was estimated using the Iron Assay Kit (MAK025, Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The data were plotted as a bar graph of iron concentration (ng/μL)/50 μg protein ± SD, n = 3.

To measure transferrin-mediated iron uptake into cells, Mtb H37Ra cells were cultured as described above, cells were washed with iron-free Sauton’s medium and incubated in the same medium with or without 32 mg/L EBP for 24 h. Cells were then washed and incubated for a further 3 h at 37°C in iron-free Sauton’s medium containing 50 μg of transferrin. Lysate preparation and iron estimation were carried out as described above. The data were plotted as a bar graph of iron concentration (ng/μL) per 50 μg of lysate ± SD, n = 3.

Cell surface transferrin binding

The effect of EBP on cell-surface sequestration of Transferrin-Alexa 647 (Tf-A647) on Mtb H37Ra cells was estimated. Mtb H37Ra was cultured to log phase and ∼2 × 108 cells were used for each assay. Cells were washed with iron-free Sauton’s medium and incubated in the same medium with or without 32 mg/L EBP for 24 h. The cells were washed with 1 × PBS and blocked for 1 h at 4°C with PBS containing 2% BSA. Cells were then incubated with 20 μg Tf-A647 (100 μL of PBS, 1% BSA) for 2 h at 4°C. Finally, cells were washed and fluorescence data of 10000 cells per sample were acquired using a Guava Soft Express Pro flow cytometer. Data were plotted as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SEM of 104 cells. Experiments were done in duplicate and performed three times independently (n = 3).

Transferrin iron uptake by calcein quenching assay

To determine reduced concentrations of iron in EBP-treated Mtb H37Ra cells, calcein fluorescence quenching was determined. Briefly, ∼2 × 108 log-phase Mtb H37Ra cells were washed with Sauton’s medium lacking iron and incubated with 32 mg/L EBP for 24 h or plain medium as a control. Cells were washed with iron-free Sauton’s medium and incubated with 1 μM calcein-AM at 37°C for 2.5 h. Cells were then washed three times with iron-free Sauton’s medium and resuspended in 0.1 mL of medium with or without 50 μg transferrin at 37°C for 6 h. Finally, cells were washed and fluorescence data of 10 000 cells per sample were acquired using a Guava Soft Express Pro flow cytometer. Data were plotted as MFI ± SEM of 104 cells. Experiments were done in duplicate and performed three times (n = 3).

Purification and inhibition of pyruvate kinase

Recombinant pyruvate kinase (PykA) was purified from strain Mtb H37Ra, which over-expresses this protein as described.9 Briefly, PykA activity was assayed using a lactate dehydrogenase-coupled assay that measures the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm resulting from the oxidation of NADH. To determine activity of Mtb PykA, a reaction mixture containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM ADP, 10 mM sodium phosphoenol pyruvate, 0.3 mM NADH and 1.5 U of lactate dehydrogenase was pre-incubated at 25°C for 5 min. PykA (250 ng) was added and the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm over 5 min was measured. For inhibition studies, Mtb PykA was pre-incubated with different concentrations of EBP (0–200 μM) at 25°C for 5 min followed by enzymatic assay. Enzyme activity in the absence of EBP was considered to be 100% and inhibition was accordingly calculated as percentage residual activity. Experiments were performed three times and a bar graph of percentage residual activity ± SD versus EBP concentration was plotted.

Purification and inhibition of Mtb glyoxylate pathway enzymes by EBP

Recombinant Mtb malate synthase (MS) and isocitrate lyase (ICL) were purified from E. coli BL21DE3 pET23-GlcB and E. coli BL21DE3 pET28-ICL, respectively. Purification was done essentially as described.11,12 MS catalyses the Claisen-like condensation; enzyme activity was measured by a coupled 4,4′-dithiodipyridine (DTP) assay that monitors the thio-ester cleavage of acetyl-CoA at 324 nm. Reactions were carried out in 100 μL of buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 200 μM DTP, 30 μM acetyl-CoA and 60 μM glyoxylate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 min, purified +Mtb GlcB enzyme (400 ng) was added to initiate the reaction and absorbance was measured. Inhibition of purified Mtb GlcB with EBP was done by pre-incubating Mtb GlcB (400 ng) with various concentrations of EBP (0–100 μM) at 25°C for 5 min followed by measurement of enzyme activity, and 800 μM oxalate was used as a standard inhibitor. Experiments were repeated three times independently with duplicates and data were plotted as percentage residual activity ± SD versus EBP concentration.13

The enzyme activity for recombinant Mtb His-ICL was determined by the phenyl hydrazine method. ICL converts isocitrate to succinate and glyoxylate. Conversion of glyoxylate to phenylhydrazone glyoxylate by the addition of phenyl hydrazine was measured at 324 nm. Purified His-ICL (1 μg/100 μL) was equilibrated at 37°C for 5 min in assay buffer [25 mM imidazole/HCL buffer (pH 6.8), 5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM phenyl hydrazine HCl and 1 mM isocitric acid] and the increase in absorbance was measured at 324 nm. Inhibition was evaluated by pre-incubating purified Mtb His-ICL with different concentrations of EBP (0–50 μM) at 37°C for 5 min followed by enzyme assay. Readings of samples without inhibitor were considered as 100% activity and residual activity was accordingly calculated in the presence of EBP. Itaconic acid was utilized at 7.69 μM as a standard inhibitor. Experiments were performed three times independently with each assay reaction done in duplicate and data were plotted as percentage residual activity ± SD versus EBP concentration.14

Determination of intracellular antimycobacterial activity of EBP

Briefly, BMDM cells were seeded in 24-well plates (∼3 × 105 cells/well) and infected with Mtb H37Rv (1:10 moi) for 3 h. Subsequently, cells were washed and treated with 100 mg/L gentamicin for 45 min to remove extracellular bacteria, following which the cells were independently treated with either 1× MIC of rifampicin (0.1 mg/L) and 1× MIC of EBP (32 mg/L) for 48 h. For cfu determination, the cells were lysed, and samples were serially diluted and plated on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates supplemented with glycerol and OADC. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 28 days and colonies were enumerated. Data were plotted as log10 cfu/mL ± SEM and experiments were performed three times in duplicate.

Activity of EBP against S. aureus biofilm

S. aureus ATCC 29213 was cultured overnight in 1% TSB on a rotary shaker at 37°C and 180 rpm. The culture was diluted 1:100 in TSB broth supplemented with 1% glucose and 0.2 mL/well was transferred into 96-well polystyrene flat-bottom tissue culture plates. Plates were covered with a lid to maintain low oxygen conditions in order to increase biofilm formation, and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the medium was decanted and the plates were rinsed gently three times with PBS (pH 7.2) to remove the planktonic bacteria. The plates were refilled with TSB containing different drug concentrations and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After drug treatment, medium was once again decanted and wells were rinsed three times with PBS. Plates were placed at 60°C for 1 h for biofilm fixation and stained with 0.06% crystal violet for 10 min. Wells were rinsed with PBS and biofilm-bound crystal violet was eluted with 30% acetic acid (0.2 mL each) and quantified by measuring absorbance at 600 nm.15 Experiments were performed twice in triplicate; data are plotted as log10 cfu/mL ± SEM.

Evaluation of in vivo antimicrobial activity using a thigh infection model

For in vivo evaluation of antimicrobial activity of EBP, BALB/C mice weighing ∼18–20 g were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneally administered cyclophosphamide injections (100 mg/kg of body weight) given 24 and 1 h before infection.7 Following induction of neutropenia, thigh infection was induced with ∼109 cfu of S. aureus ATCC 29213. Three hours after infection, EBP (1 mg/kg) and vancomycin (25 mg/kg) were injected intraperitoneally (ip) into mice, twice with an interval of 3 h between injections. Control animals were administered saline at the same volume and frequency as those receiving treatment. After 24 h, animals were sacrificed; thigh tissue was collected, weighed and homogenized in 5 mL of saline. The homogenate was serially diluted and plated on MHA plates for cfu determination. After incubation for 18–24 h at 37°C, cfu were enumerated, and data were averaged across three experiments and plotted as log10 cfu/mL.

Ethics approval

The use of mice for infection studies (IAEC/2014/139 dated 03.12.2014) was approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee at CSIR-CDRI, Lucknow.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Comparison between three or more groups was analysed using one-way ANOVA, with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and Student’s t-test. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Inhibition of ESKAPE pathogens and Mtb by EBP

The antibacterial activity of EBP was evaluated against Mtb H37Rv, drug-resistant Mtb strains and the ESKAPE pathogen panel, including clinical drug-resistant strains of S. aureus (Figure 1a). As seen in Table 1, EBP exhibited an MIC of 32–64 mg/L against all bacterial strains tested irrespective of their drug resistance status. Altogether, EBP was equally potent against drug-susceptible as well as drug-resistant mycobacterial and ESKAPE strains, thus indicating a potentially new mechanism of action and lack of cross-resistance with existing drug resistance mechanisms.

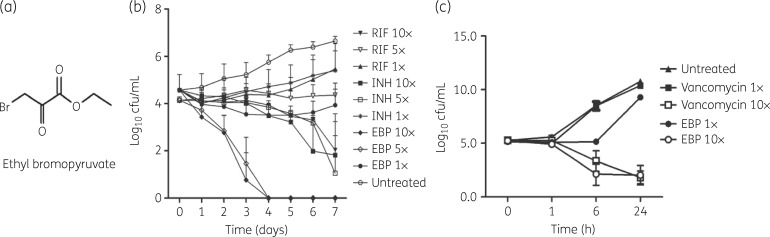

Figure 1.

EBP-induced growth inhibition of Mtb and S. aureus. (a) Structure of EBP. (b) Time-dependent killing of Mtb by isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF) and EBP at 1×, 5× and 10× MIC. Data are plotted as log10 cfu/mL ± SEM versus time. (c) Time-dependent killing of S. aureus by vancomycin and EBP at 1× and 10× MIC. Data are plotted as log10 cfu/mL ± SEM versus time.

Table 1.

MIC of EBP against drug-susceptible and -resistant bacterial pathogens

| Bacteria | Resistance profile | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | ||

| H37Rv ATCC 27294 | susceptible | 32.0 |

| ATCC 35838 | RIF | 32.0 |

| ATCC 35822 | INH | 64.0 |

| ATCC 35820 | STR | 64.0 |

| ATCC 35837 | ETB | 32.0 |

| S. aureus | ||

| ATCC 29213 | susceptible | 64.0 |

| NARSA 129 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 192 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 198 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 191 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 193 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 186 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 100 | MET, CRO, MEM | 64.0 |

| NARSA 119 | MET, CRO, MEM, GEN, LZD | 32.0 |

| NARSA 194 | MET, CRO | 64.0 |

| VRSA 1 | MET, CRO, MEM, GEN, VAN, TEC | 64.0 |

| VRSA 4 | MET, CRO, MEM, VAN, TEC | 64.0 |

| VRSA 12 | MET, CRO, MEM, VAN, TEC | 64.0 |

| Gram-negative pathogens | ||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | susceptible | 32.0 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | susceptible | 64.0 |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | susceptible | 32.0 |

| A. baumannii BAA-1605 | CAZ, GEN, TIC, PIP, ATM, FEP, CIP, IPM, MEM | 64.0 |

| K. pneumoniae BAA-1705 | IPM, MEM | 32.0 |

RIF, rifampicin; INH, isoniazid; STR, streptomycin; ETB, ethambutol; MET, methicillin; CRO, ceftriaxone; MEM, meropenem; GEN, gentamicin; LZD, linezolid; VAN, vancomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; PIP, piperacillin; TIC, ticarcillin; FEP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; IPM, imipenem.

Selectivity index of EBP

The CC50 of EBP was determined against BMDM cells to be >320 mg/L at 48 h; thus, the selectivity index (CC50/MIC) was calculated to be >10, which is quite acceptable for drug-repurposing efforts.

Kill kinetics of EBP against Mtb and S. aureus

After determining the antimicrobial potential of EBP, we assessed the bacterial killing kinetics at 1×, 5× and 10× MIC of EBP. Isoniazid and rifampicin were utilized as controls for Mtb while vancomycin was used as a control for S. aureus. In comparison with 5× MIC of isoniazid or rifampicin, EBP exhibited potent killing of Mtb at 5× MIC (∼6 log10 cfu/mL), with no viable cells being recovered after 4 days of incubation (Figure 1b). With S. aureus, EBP exhibited a ∼9 log10 cfu/mL reduction at 10× MIC in 24 h compared with the no-drug control. This reduction is closely comparable to vancomycin, which exhibited ∼9 log10 reduction at 10× MIC (Figure 1c). Taken together, these results indicate that EBP exhibits significant concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against Mtb and S. aureus.

Synergy of EBP with FDA-approved drugs

Since a combination of drugs is often required for treatment of infectious diseases, the ability of EBP to synergize with other drugs was determined using the chequerboard method. As shown in Table 2, the FIC index was calculated to be 1.5 for rifampicin and 2 for isoniazid, indicating no interaction with both front-line drugs. Similarly, EBP did not interact with vancomycin, levofloxacin, ceftazidime, linezolid or gentamicin (FIC 1.5–2), which are typically utilized against S. aureus.

Table 2.

Synergy of EBP with first-line anti-Mtb and anti-staphylococcal drugs

| MIC (mg/L) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism/drug | drug alone | drug in presence of EBP | EBP | EBP in presence of drug | FIC index | Indication |

| M. tuberculosis | ||||||

| rifampicin | 0.06 | 0.03 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 1.5 | no interaction |

| isoniazid | 0.03 | 0.03 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 2.0 | no interaction |

| S. aureus | ||||||

| vancomycin | 1 | 2 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 1.5 | no interaction |

| levofloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 64.0 | 32.0 | 1.25 | no interaction |

| ceftazidime | 8 | 8 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 2 | no interaction |

| linezolid | 2 | 1 | 64.0 | 32.0 | 1.5 | no interaction |

| gentamicin | 0.25 | 0.125 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 1.5 | no interaction |

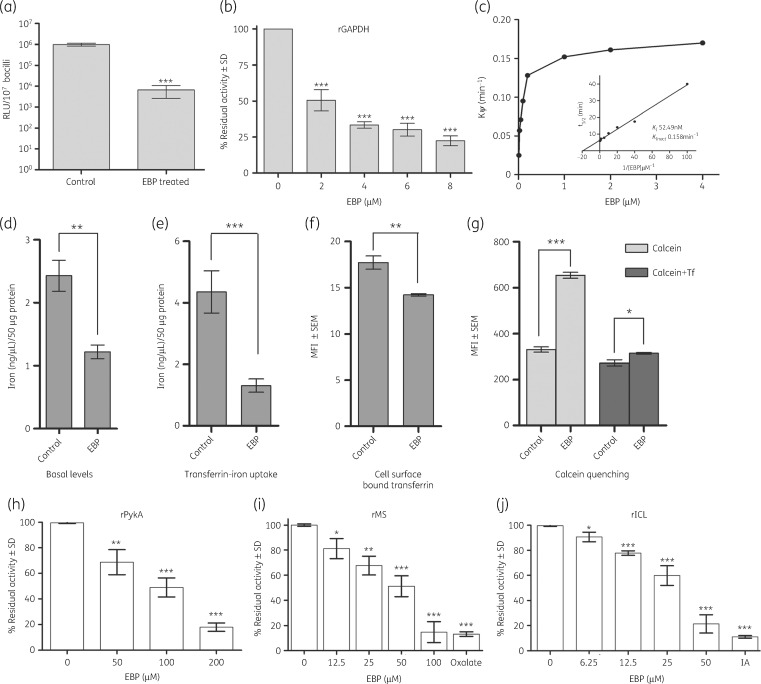

EBP reduces cellular ATP in replicative bacilli

Since 3-BPA is known to inhibit ATP synthesis, we assessed the effect of EBP on cellular ATP levels in Mtb.16 A significant decrease in intracellular ATP levels was evident in EBP-treated Mtb cells (1× MIC) (P < 0.001) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

EBP inhibits multiple enzymes and transferrin iron uptake in Mtb. (a) EBP treatment of Mtb H37Ra results in a significant decrease in the intracellular concentration of ATP (***P < 0.0001). (b) Mtb rGAPDH was inhibited by increasing concentrations of EBP. (c) Determination of Ki value for EBP against recombinant Mtb GAPDH. (d) Basal cellular iron concentrations are decreased in EBP-treated bacilli (**P < 0.005). Data are plotted as iron (ng/μL) per 50 μg of protein ± SD, n = 3. (e) EBP-treated Mtb cells demonstrate significant reduction in transferrin iron uptake (***P < 0.0001). Data are plotted as iron (ng/μL) per 50 μg of protein ± SD, n = 3. (f) The cell surface sequestration of Tf-A647 is significantly reduced in EBP-treated cells, as determined using Student’s t-test (**P < 0.005). Data are plotted as MFI ± SEM of 104 cells; experiments were done in duplicate and repeated three times (n = 3). (g) Calcein quenching assay confirms that EBP treatment reduces basal iron concentration (***P < 0.0001) and transferrin iron acquisition (*P < 0.01) compared with untreated controls. Data are plotted as MFI ± SEM of 104 cells; experiments were done in duplicate and repeated three times (n = 3). Significance was determined using Student’s t-test. (h) Recombinant Mtb PykA (rPykA) was significantly inhibited by EBP in the range of 50–200 μM. Recombinant Mtb glyoxylate pathway enzymes (i) MS (rMS) and (j) rICL are inhibited by EBP in the range 6.25–50 and 12.5–100 μM, respectively. IA, itaconic acid, a known inhibitor of ICL. Data are plotted as percentage residual activity ± SD compared with enzyme without EBP. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

Inhibition of Mtb GAPDH by EBP and determination of Ki

Since the primary target of 3-BPA in cancer cells is reported to be GAPDH, which has a high degree of conservation across species, we evaluated whether this enzyme was a target in Mtb. To confirm our findings, we purified Mtb GAPDH and determined 75% inhibition of GAPDH activity at 8 μM (1.56 mg/L) of EBP (Figure 2b). A Kitz–Wilson re-plot of EBP gave a kinactivation and Ki of 0.158 min−1 and 52.49 nM respectively. The inhibition of Mtb GAPDH occurred in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2c).

Inhibition of GAPDH-mediated transferrin uptake

Since Mtb GAPDH also serves as a transferrin receptor and enhances iron uptake in Mtb cells, we evaluated whether EBP also affects this function. Our results demonstrate that the basal iron concentrations of the EBP-treated Mtb H37Ra cultures were reduced by >2-fold compared with untreated controls (Figure 2d) (P < 0.005). Transferrin-mediated iron uptake was reduced by 70% (P < 0.0001) in EBP-treated H37Ra cultures compared with untreated controls (Figure 2e). To determine whether cell surface binding of transferrin is affected by EBP treatment, the surface binding of Tf-A647 was measured and found to be significantly reduced compared with untreated controls (P < 0.005) (Figure 2f). Lastly, calcein fluorescence staining was utilized, which indicates viability while quenching indicates increased iron levels. In concurrence with results for basal iron levels, the untreated cells showed reduced fluorescence, indicative of higher iron concentrations, while EBP-treated Mtb H37Ra cells revealed significantly higher fluorescence, indicative of lower basal cellular iron (P < 0.0001). Upon addition of transferrin, untreated cells demonstrated enhanced iron uptake (indicated by more calcein quenching) compared with EBP-treated cells (P < 0.01) (Figure 2g).

Effect of EBP on PykA

Inhibition was tested against PykA, with a concentration-dependent inhibition of PykA being observed at concentrations of 50–200 μM (9.75–39 mg/L). At 200 μM EBP there was ∼80% inhibition (Figure 2h).

Inhibition of enzymes of glyoxylate pathway

The glyoxylate shunt pathway consists of ICL and MS and is a mechanism of survival during latency. EBP inhibited MS by ∼75% at 100 μM (19.5 mg/L) (Figure 2i). As described previously, ICL was inhibited by EBP, with a reported Ki value of 120 μM.17 Inhibition was assessed at concentrations ranging from 6.25 to 50 μM (1.21–9.75 mg/L); ∼80% inhibition was observed at 50 μM EBP (Figure 2j). Taken together, these results indicate that EBP inhibits all enzymes at near or below MIC values.

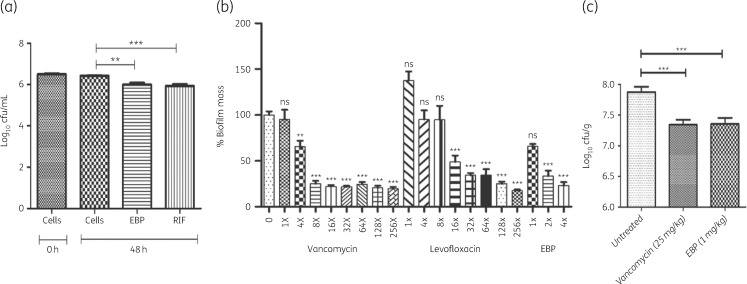

EBP potently reduces intracellular mycobacterial load

The effect of EBP against intracellular Mtb H37Rv was determined in BMDM cells. As can be seen in Figure 3(a), EBP at 1× MIC significantly reduced the mycobacterial load (P < 0.01), which is comparable to the effect of rifampicin (P < 0.001). This is significant since intracellular mycobacteria often act as a reservoir for recurrent infection. Thus, EBP’s potent activity against intracellular mycobacteria is a positive indication.

Figure 3.

Intracellular killing of Mtb and S. aureus growth inhibition by EBP. (a) Intracellular Mtb bacilli are inhibited by EBP treatment. Data are plotted as log10 cfu/mL. Rifampicin (RIF) was utilized as a positive control. (b) Inhibition of S. aureus biofilm in the presence of varying MICs of vancomycin, levofloxacin and EBP. (c) In vivo antimicrobial activity using the thigh infection model. The known inhibitor vancomycin was evaluated at 25 mg/kg while EBP gave an equivalent response at 1 mg/kg. Significance is indicated as: **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

EBP inhibits S. aureus biofilm

Biofilm formation is the hallmark of serious staphylococcal infections, and thus activity of EBP against biofilms was investigated. EBP caused ∼75% reduction in biofilm mass at 2× MIC, and 128× MIC of levofloxacin and 8× MIC of vancomycin achieved the same amount of inhibition (Figure 3b). Thus, EBP is 64-fold better than levofloxacin and 4-fold better than vancomycin against staphylococcal biofilms.

In vivo antimicrobial activity of EBP in neutropenic S. aureus thigh infection model

Since EBP exhibited potent in vitro antimicrobial activity, we evaluated its in vivo efficacy in a murine neutropenic S. aureus thigh infection model. Briefly, infected mice were treated with vancomycin (25 mg/kg) and EBP (1 mg/kg), twice with a 3 h difference between treatments. As seen in Figure 3c, treatment with EBP significantly reduced mean bacterial counts compared with the control group (∼0.6 log10), which is comparable to the effect seen with vancomycin. These results reveal that EBP is as effective as vancomycin in reducing the bacterial load in infected mice, even at 1/25th of the dosage.

Discussion

The increasing incidence of drug-resistant infections is an emerging crisis worldwide. Although extensive efforts are being made to identify and develop new drug candidates, the process is slow with a high attrition rate. Given the length of time required for traditional drug discovery, drug repurposing offers the possibility of shortening the development process. 3-BPA has been reported as an effective inhibitor in numerous animal models of cancer and is an electrophilic alkylator that non-specifically inhibits multiple targets, with GAPDH as the primary target.16,18,19 Other targets include hexokinase, PykA, lactate dehydrogenase and succinate dehydrogenase.18 It has been demonstrated that aerosol delivery of 3-BPA was effective in treatment of murine lung cancer, with significantly lower toxicity than oral gavage.20

It is important to note that Mtb-infected cells exhibit the hallmarks of the Warburg effect.21,22 Virulent Mtb bacilli manipulate the host metabolic machinery to (i) enhance the uptake of glucose and (ii) synthesize G3P at the payoff step. Previous studies have demonstrated that during infection virulent Mtb bacilli reprogramme host metabolism to synthesize citrate for the onward synthesis of lipids required for bacterial survival. Upon infection with attenuated Mtb strains, the host apoptotic pathway is induced, whereas infection with virulent bacilli triggers a necrotic response to enable spread of the pathogen. When cells were infected with virulent bacilli and subsequently treated with 3-BPA, an apoptotic response was induced due to reduction of ATP synthesis.21 These findings suggest that EBP could play a dual role by not only inhibiting Mtb GAPDH but also by inhibiting the homologous host enzymes responsible for the Warburg effect in infected cells.

The current study determined the potential of EBP as a broad-spectrum antibacterial agent. EBP exhibited equipotent inhibition towards drug-susceptible and drug-resistant Mtb and ESKAPE pathogens with an MIC of 32–64 mg/L. Detailed studies revealed that EBP exhibited concentration-dependent bactericidal killing kinetics and outperformed isoniazid and rifampicin against Mtb, while against S. aureus EBP’s killing activity was comparable to that of vancomycin. Additionally, it did not negatively interact with any drug tested. Our studies demonstrate that EBP targets multiple Mtb enzymes of the glycolytic and glyoxylate pathways as it inhibits GAPDH, PykA, ICL and MS. It is relevant that GAPDH from multiple bacterial species is known to moonlight as a transferrin receptor, an adhesin and an invasin.23–25 Our study demonstrates that EBP also targets iron uptake by reducing surface binding of transferrin and ultimately transferrin-associated iron acquisition in Mtb. In vivo studies using a murine neutropenic thigh infection model demonstrated EBP’s superior efficacy compared with vancomycin, at 1/25th of the dosage. It is relevant to mention that most MDR nosocomial infections persist due to biofilm formation in catheters and infection of chronic wounds. Since biofilm formation is critical for the pathogenesis of S. aureus, we assessed whether biofilm formation is disrupted upon treatment with EBP. Intriguingly, S. aureus GAPDH is known to be released extracellularly where it plays a role in biofilm formation.24,25

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that EBP-mediated inhibition of multiple targets could be used to exploit the parallel changes in the metabolic programming of TB-infected macrophages. This study demonstrates for the first time that conserved multifunctional proteins can be considered as potential antibacterial targets. The fact that EBP is effective against multiple enzymes of the glycolytic and glyoxylate pathways support its potential use as an effective antimicrobial strategy. Lastly, such compounds appear to target not only the primary metabolic functions but also inhibit the numerous alternative functions that are vital for bacterial pathogenesis.

Acknowledgements

Mr Ranvir Singh is acknowledged for the skilful technical assistance provided for the experiments. V. M. B was a recipient of a Research Associateship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. A. K. and Z. G. were recipients of research fellowships provided by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (grants BT/PR13469/BRB/10/1396/2015 and BT/HRD/NBA/37/01/2014, respectively). A. P. was a recipient of a research fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT). R. T., A. K. S and S. D. thank CSIR for their research fellowships. The following reagents were provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) for distribution by BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: NR 119, NR 100, NR 10129, NR 10198, NR 10192, NR 10191, NR 10193, NR 10186, NR 10194, VRS1, VRS4 and VRS12.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), SAS, Nagar and Council of Scientific Research (CSIR), Govt. of India.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

- 1. Maitra A, Bates S, Kolvekar T. et al. Repurposing—a ray of hope in tackling extensive drug resistance in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis 2015; 32: 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rangel-Vega A, Bernstein LR, Mandujano Tinoco E-A. et al. Drug repurposing as an alternative for the treatment of recalcitrant bacterial infections. Front Microbiol 2015; 6: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin DS, Bertino JR, Koutcher J.. In-vivo energy depleting strategies for killing drug-resistant cancer cells In: Patent US, ed. USA: Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research. New York, NY. USA, United States Patent Application US7514413B2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically—Ninth Edition: Approved Standard M07-A9. CLSI, Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM.. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol 2008; 81: 14.1.1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trouplin V, Boucherit N, Gorvel L. et al. Bone marrow-derived macrophage production. J Vis Exp 2013; 81: e50966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thakare R, Singh AK, Das S. et al. Repurposing ivacaftor for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017; 50: 389–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Odds FC. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003; 52: 1.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boradia VM, Patil P, Agnihotri A. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra: a surrogate for the expression of conserved, multimeric proteins of M.tb H37Rv. Microb Cell Fact 2016; 15: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kitz R, Wilson IB.. Esters of methanesulfonic acid as irreversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem 1962; 237: 3245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith CV, Huang C-c, Miczak A. et al. Biochemical and structural studies of malate synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 1735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ji L, Long Q, Yang D. et al. Identification of mannich base as a novel inhibitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate by high-throughput screening. Int J Biol Sci 2011; 7: 376.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Quartararo CE, Blanchard JS.. Kinetic and chemical mechanism of malate synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry 2011; 50: 6879–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rúa J, de Arriaga D, Busto F. et al. Isocitrate lyase from Phycomyces blakesleeanus. The role of Mg2+ ions, kinetics and evidence for two classes of modifiable thiol groups. Biochem J 1990; 272: 359–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kwasny SM, Opperman TJ.. Static biofilm cultures of Gram-positive pathogens grown in a microtiter format used for anti-biofilm drug discovery. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 2010; 50: 13A.8.1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ganapathy-Kanniappan S, Geschwind J-FH, Kunjithapatham R. et al. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is pyruvylated during 3-bromopyruvate mediated cancer cell death. Anticancer Res 2009; 29: 4909–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma V, Sharma S, zu Bentrup KH. et al. Structure of isocitrate lyase, a persistence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Struct Biol 2000; 7: 663.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shoshan MC. 3-Bromopyruvate: targets and outcomes. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2012; 44: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pedersen PL3. Bromopyruvate (3BP) a fast acting, promising, powerful, specific, and effective ‘small molecule’ anti-cancer agent taken from labside to bedside: introduction to a special issue. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2012; 44: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang Q, Pan J, North PE. et al. Aerosolized 3-bromopyruvate inhibits lung tumorigenesis without causing liver toxicity. Cancer Prev Res 2012; 5: 717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehrotra P, Jamwal SV, Saquib N. et al. Pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is expressed by regulating metabolic thresholds of the host macrophage. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10: e1004265.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shi L, Salamon H, Eugenin EA. et al. Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces the Warburg effect in mouse lungs. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 18176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boradia VM, Malhotra H, Thakkar JS. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis acquires iron by cell-surface sequestration and internalization of human holo-transferrin. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Foulston L, Elsholz AK, DeFrancesco AS. et al. The extracellular matrix of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms comprises cytoplasmic proteins that associate with the cell surface in response to decreasing pH. mBio 2014; 5: e01667–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Modun B, Williams P.. The staphylococcal transferrin-binding protein is a cell wall glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Infect Immun 1999; 67: 1086–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]