Abstract

The effect of subculture cycles on somaclonal variation of V. planifolia using intersimple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers was analyzed. Nodal segments of 2 cm in length were established in vitro and multiplied by 10 subculture cycles in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 8.86 μM BAP (benzylaminopurine). After 45 days in each culture, the length and number of shoots per explant were evaluated. For ISSR markers, ten shoots per each subculture and the mother plant were used. Ten ISSR primers were used and a total of 118 bands were obtained. The polymorphism (%) was calculated and a dendrogram based on Jaccard’s genetic distance between the subcultures and the donor plant was obtained. These results show that the multiplication rate tends to increase until subculture five, whereas shoot length decreases as the number of subcultures increases. The ISSR markers revealed an increase in the polymorphism percentage after the fifth culture cycle. The dendrogram showed the formation of two groups. The first group, with less genetic variability, is the donor plant and subcultures 1–5; the second group has greater genetic distance and is formed by subcultures 6–10. The results revealed that the number of subcultures with 8.86 μM BAP is a factor that affects the somaclonal variation during in vitro regeneration of V. planifolia. In conclusion, the subculture number affects somaclonal variation and in vitro development of V. planifolia.

Keywords: Vanilla planifolia, Regeneration, Somaclonal variation, Micropropagation, ISSR

Introduction

In vitro plant regeneration is an effective tool for generation of high-quality, disease-free and uniform planting material (Azman et al. 2014). However, even though micropropagation provides many advantages, genetic instability has been observed. Larkin and Scowcroft (1981) described somaclonal variation as the epigenetic and genetic changes of in vitro plant regeneration. According to Lázaro-Castellanos et al. (2018), genetic instability is a problem during commercial micropropagation. However, contrary to the negative effects of somaclonal variation, genetic changes can also be an important tool for generation of new varieties that could exhibit disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance and improvement in quality and yield (Jain et al. 2013; Krishna et al. 2016).

During in vitro culture, the type and concentration of growth regulators, propagation methods and the number as well as the duration of subcultures are key factors that determine the frequency of somaclonal variation (Krishna et al. 2016). In particular, the number of subcultures performed is strictly related to the levels of somaclonal variation detected (Peng et al. 2015; Martínez-Estrada et al. 2017; Mamedes-Rodrigues et al. 2018). Somaclonal variants can be detected using various physiological, morphological, biochemical and molecular methods (Bairu et al. 2011). Among molecular markers, one of the most used for detecting genetic variability is the intersimple sequence repeat (ISSR) (Akdemir et al. 2016; Martínez-Estrada et al. 2017; Babu et al. 2018). This technique uses microsatellites as primers in a single primer PCR reaction to amplify inter-SSR sequences of different sizes (Reddy et al. 2002). In addition, ISSR makers are highly polymorphic, the technique is quick, simple, and reproducible and it does not require prior information about the genome (Peng et al. 2015).

Vanillin is one of the most valued substances in fragrance, pharmaceutical and food industries worldwide (Bory et al. 2008; Greule et al. 2010) and is extracted from the fruits of the genus Vanilla (Salazar-Rojas et al. 2012), especially Vanilla planifolia, from which 95% of the world production is obtained (Bory et al. 2008). Despite its importance, in Mexico, V. planifolia is considered a species subject to special protection due to the severe damage that its natural habitat has suffered, the premature fall of fruits (Lee-Espinosa et al. 2008), and the reduction of its genetic diversity caused by the conventional cuttings-based propagation method (Gantait and Kundu 2017). Today, there are different protocols for in vitro propagation of V. planifolia (Sreedhar et al. 2007; Lee-Espinosa et al. 2008; Ramos-Castellá et al. 2014; Gantait and Kundu 2017). However, in most of these studies, the levels of somaclonal variation were not analyzed. In this context, high levels of somaclonal variation were reported during regeneration from callus in V. planifolia (Divakaran et al. 2015; Ramírez-Mosqueda and Iglesias-Andreu 2015). These works suggest that indirect morphogenesis is an alternative to generate genetic diversity in this important crop.

In order to avoid the work required for the establishment of new explants, it is necessary to know clonal fidelity during subculture number when the objective is commercial micropropagation. In this sense, the aim of this research was to determine the morphological and molecular variation of in vitro-propagated plants of V. planifolia at different subcultures using ISSR molecular markers.

Materials and methods

Plant material and in vitro culture establishment

Stems of 40–50 cm in length were cut from 6-month-old V. planifolia plantlets in a commercial plantation in Veracruz, Mexico. The cuttings were kept under greenhouse conditions for 6 months. After that, the leaves were removed and nodal segments (with a bud) of 2 cm in length were cut off for use as explants. These were washed with tap water and commercial soap for 1 h. The nodal segments were immersed in 0.2% (w/v) 50PH Captan (N-trichloromethylthio-4-cyclohexene-1,2-dicarboximide) for 30 min, followed by 70% ethanol (v/v) for 1 min and three rinses with sterile distilled water. Finally, nodal segments were immersed in sodium hypochlorite at 0.6 and 0.3% (v/v) for 10 and 5 min, respectively, and then rinsed three times with sterile distilled water.

The explants were individually transferred into 45 mL flasks containing 10 mL of Murashige and Skoog (1962) basal medium without growth regulators supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose. The MS medium was adjusted to pH 5.7 with 0.5 N sodium hydroxide, and 0.27% (w/v) Phytagel® (Sigma Chemical Company, MO, USA) was added as a gelling agent before being sterilized in an autoclave at 120 °C and 117.7 kPa for 15 min. All cultures were incubated at 25 ± 2 °C with a photoperiod of 16 h under fluorescent light (40 to 50 μmol m−1 s−1).

Effect of subculture cycles on shoot multiplication

The effect of subculture cycles on multiplication rate (expressed as number of shoots per explant) and somaclonal variation were evaluated during V. planifolia micropropagation. Vanilla shoots derived from stock cultures multiplied on semisolid MS medium were subcultured. Each subculture consisted of a transfer to a fresh medium. This culture medium consisted of MS basal medium supplemented with 8.86 μM benzylaminopurine (BAP) (Sigma Chemical Company, MO, USA). Three explants were placed in each flask containing 20 mL of medium. The number of shoots per explants and shoot length as expressed in cm were recorded. Fifteen explants per subculture were used and this was considered as a replicate. Ten subcultures were performed at 45-day intervals over a total period of 450 days.

Experimental design and data analysis

The experiments were conducted using a completely randomized design. All experiments were carried out in triplicate. The statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s comparison of means test (P ≤ 0.05) was performed using SPSS statistical software (version 22 for Windows). When required, data were transformed to natural logarithm (In) to achieve normality and equal variance.

DNA isolation

Leaf samples (0.5 g) from the mother plant and leaves from ten randomly-selected shoots per culture cycle were used for DNA extraction. The extraction was performed according to the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method (Stewart and Via 1993). The extraction was carried out in duplicate for each sample. The amount and purity of genomic DNA were determined by spectrophotometry (Genesys 10S UVVIS, Thermo Scientific, IL, USA). DNA integrity was verified in 1% (w/v) agarose gel stained with 2.53 µM ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich®), visualized in a UV light using a GelDoc-It photodocumentation system (UVP, Upland, Canada).

ISSR-PCR analysis

To screen genomic DNA polymorphism in V. planifolia, 30 ISSR primers (Sigma-Aldrich®) were evaluated. Based on resolution and reproducibility of banding patterns, 10 primers were selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

ISSR primers used for detecting somaclonal variation in vanilla (V. planifolia)

| Primers | Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm | No. of bands | Range (bp) | Polymorphism (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBC-809 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGG | 45 | 13 | 200–1000 | 13.5 |

| T06 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGT | 50 | 10 | 300–1550 | 16.1 |

| UBC-840 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAYT | 50 | 12 | 200–1000 | 31.3 |

| UBC-836 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGYA | 50 | 12 | 200–1550 | 12.7 |

| UBC-812 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAA | 50 | 14 | 200–1400 | 21.1 |

| UBC-825 | ACACACACACACACACT | 51 | 11 | 500–3000 | 3.3 |

| UBC-808 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAGC | 52 | 15 | 200–750 | 0 |

| T05 | CGTTGTGTGTGTGTGTGT | 54 | 10 | 300–2000 | 0 |

| C07 | GAGAGAGAGAGAGAGAC | 56 | 11 | 300–1400 | 3.3 |

| UBC-857 | ACACACACACACACACYG | 57 | 10 | 300–700 | 0 |

Tm = annealing temperature; bp = base pair; Y = C or T residues

The reactions were carried out in a final volume of 25 μL containing 50 ng of DNA template, 1 × PCR reaction buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl and 50 mM KCl), 2.5 mM of MgCl2, 0.2 mM of dNTPs, 0.2 μM of primer, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, MO, USA). PCR products were amplified using a MaxyGene™ thermocycler (Axygen® Inc., Union City, CA, USA) under the following program: a cycle at 94 °C for 4 min; followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 50 s, at different annealing temperature for each primer (45–57 °C) for 50 s and 72 °C for 90 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR amplified products were resolved on 3% (w/v) agarose gels in 1 × TAE buffer at 90 V for 90 min and stained with ethidium bromide (2.53 µM). A DNA ladder (50–10,000 bp, Sigma-Aldrich®) was used as a molecular weight marker. Finally, PCR products were photographed using the photodocumentation system previously described.

Molecular data analysis

ISSR fragments were scored as present (1) or absent (0), resulting in a matrix of binary values, and the genetic distances were analyzed using TFPGA software (Tools for Population Genetic Analyses, Miller 1997). Polymorphism (%) was calculated for each subculture. In addition, a cluster analysis based on Jaccard distances was carried out considering a neighbor joining (NJ) agglomeration model where the donor plant was considered as an external group. The NJ clustering was performed after bootstrapping 1000 times. The results were obtained using the Past v 3.04 program (Hammer et al. 2001) and were expressed as a dendrogram.

Results and Discussion

Effect of subculture cycles on shoot multiplication

The number and length of shoots showed significant differences among subculture cycles. The lowest number of shoots per explant was observed during subcultures one to five, while the maximum multiplication rate was observed in subcultures six to ten. Regarding shoot length, as the number of subcultures increases, a decrease in shoot length is observed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of subculture cycles on shoot length (a) and shoots per explant (b) during Vanilla planifolia micropropagation. Mean ± SE (standard error) within a bar followed by different letters are statistically different (Tukey test (p ≤ 0.05), p < 0.05)

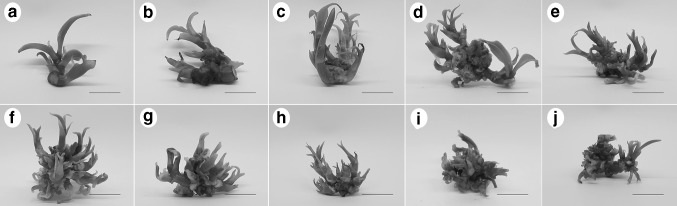

The results obtained in this study show that subculture cycles have an effect on the multiplication rate and shoot length in V. planifolia micropropagation (Fig. 2). Similar to our results, multiplication rate and shoot length have been shown to decrease as the number of subcultures increases. In an early study, Lee (1987) evaluated the in vitro multiplication of Saccharum spp. during ten subcultures and observed a reduction in shoot regeneration between the fifth and tenth subculture, obtaining morphologically normal shoots until subculture seven. Mendes et al. (1999) in Musa spp. reported a decrease in shoot production in semisolid medium from the fourth subculture. In Aloe vera, Kanwar et al. (2015) reported that the shoot production in the first subculture is lower compared to those obtained in the sixth subculture. From this subculture, they also observed a decrease in shoot number and length. Recently, Martínez-Estrada et al. (2017) reported that the maximum shoot production of Saccharum spp. in temporary immersion is obtained in the eighth subculture. The increase in somaclonal variation in aged cultures or with several subcultures has been reported in several species such as Saccharum spp. (Lee 1987; Martínez-Estrada et al. 2017), Musa spp. (Bairu et al. 2006) and Stevia rebaudiana (Soliman et al. 2014).

Fig. 2.

Effect of subculture cycles on number of shoots per explant and shoot length in Vanilla (V. planifolia). a–j Subcultures 1 to 10, respectively. Bar = 1 cm

Effect of subculture cycles on somaclonal variation

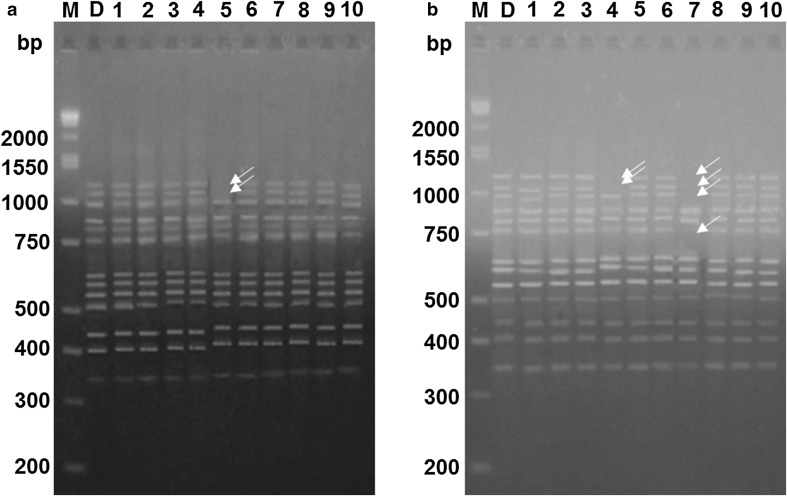

The ISSR analysis presented the existence of polymorphism among the subcultures. A total of 118 fragments of between 200 and 2000 bp were amplified. The lowest polymorphism was found in the shoots obtained from the first subculture, with 0.84% polymorphism. The shoots obtained in subcultures 2–5 showed less than 4% polymorphism. However, from the sixth subculture, percentages of polymorphism greater than 15% were observed, with subculture ten having the highest percentage, with 19.49% (Fig. 3). In Fig. 4, ISSR banding profiles show polymorphic bands in different subculture cycles.

Fig. 3.

Effect of subculture cycles on polymorphism percentage during in vitro V. planifolia propagation assessed by ISSR markers

Fig. 4.

Electrophoresis pattern of ISSR molecular markers generated ten plants of each culture cycle with respect to the donor plant. a Subculture 5, primer UBC 809 and b subculture 6, primer UBC 809. D = donor plant, M = molecular mass marker and bp = base pairs

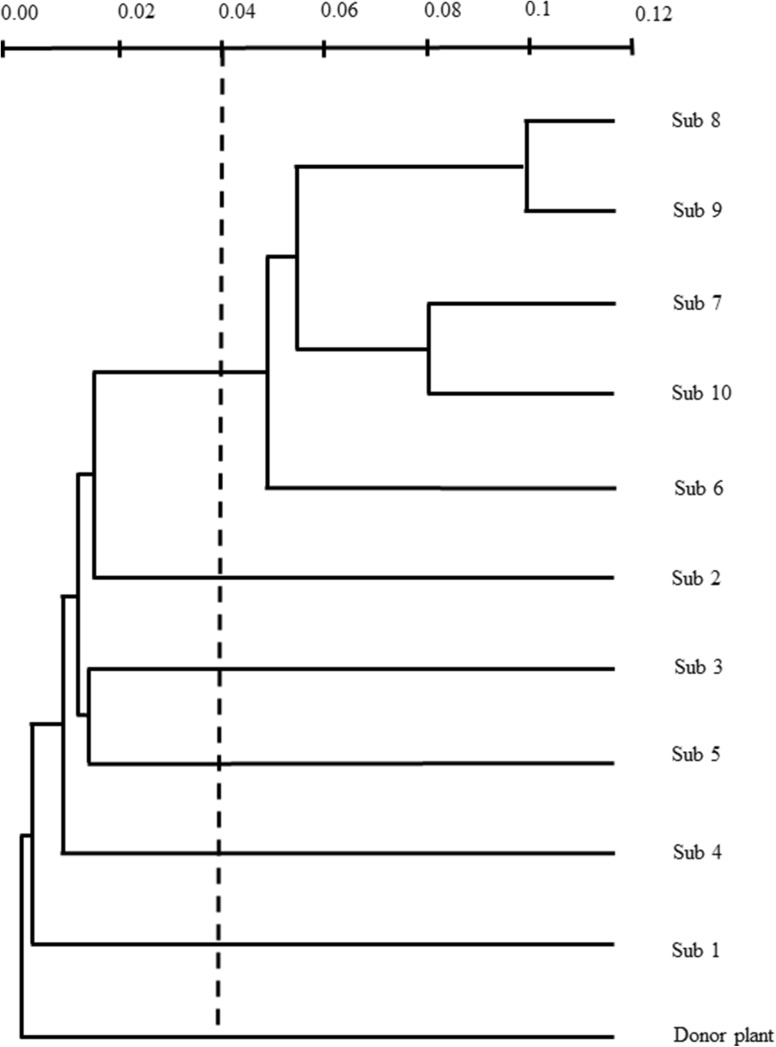

According to cluster analyses, the dendrogram showed the formation of two groups. The first group is formed by the donor plant and subcultures one to five, while the second group comprises subcultures six to ten. According to the probabilities by Bootstrap, the cut distance and the length of the branches, the first group can be considered to have less genetic distance with respect to the donor plant, while the second group corresponds to the genetically more distant one with respect to the donor plant, with Jaccard genetic distances of 0.1 and 0.08 for the first and second group, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Genetic similarity dendrogram based on Jaccard’s coefficient by a neighbor joining agglomeration model. The analysis was calculated for each culture cycle with respect to the donor plant

Molecular analysis has detected somaclonal variation in other species. Khan et al. (2011), in Musa spp., observed that after subculture eight, the percentage of somaclonal variants detected by SSR and RAPD increased with a simultaneous decrease in shoot regeneration. Farahani et al. (2011), in Olea europea, found morphological characters and genetic changes among the regenerated plants after subculture seven. Similar results were reported by Soliman et al. (2014) and Kılınç et al. (2015) in Stevia rebaudiana and Pistacia lentiscus, respectively, in which the greatest genetic instability was found in the highest number of subcultures.

Somaclonal variation has been detected in different micropropagated plant species through ISSR markers (Bello-Bello et al. 2014; Martínez-Estrada et al. 2017; Babu et al. 2018). However, although V. planifolia micropropagation has been widely studied, there are few reports on the analysis of somaclonal variation. Sreedhar et al. (2007) reported that there was no somaclonal variation in the long-term culture of V. planifolia using RAPD and ISSR molecular markers. Similarly, Gantait et al. (2009) reported that there was no somaclonal variation after five subcultures using ISSR markers. These results coincide with those obtained in this study, since the percentage of somaclonal variation detected in the first subcultures is practically null, demonstrating that V. planifolia presents genetic stability at least in the first five subcultures.

The presence of somaclonal variation by increasing the subculture cycles could be explained under different hypotheses. Jain (2001) mentioned that the in vitro culture process acts as a mutagenic system and may reprogram during plant regeneration. This effect increases as the time and number of subcultures increases, adding new somaclonal variants to each subculture. Another possibility is related to the strong correlation that has been shown between the multiplication rate and genetic variability, which tended to be higher as the shoot production increased. Additionally, the growth regulators are factors that can induce genetic variability. There is probably an endogenous accumulation of growth regulators in the explant that favors an increase in the multiplication rate during the first subcultures, whereas when high concentrations of growth regulators accumulate, there is an inhibition of growth and differentiation, causing the excess regulators to act as a mutagenic agent. According to Sales and Butardo (2014), several growth regulators, such as NAA (naphthalene acetic acid), 2,4-d (2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid) and BAP (6-benzylaminopurine), have been most considered to be responsible for obtaining in vitro genetic instability. In this study, probably the endogenous BAP accumulation together with the number of subcultures caused the increase in somaclonal variation after the fifth subculture.

Historically, tissue culture was seen as a method of cloning a particular genotype. It was often considered a sophisticated method of asexual propagation enabling a more rapid rate of propagation (Larkin and Scowcroft 1981). However, somaclonal variation among micropropagated plants derived through the culture of organized meristems (Rani and Raina 2000), vegetative buds (Martínez-Estrada et al. 2017) and nodal cuttings (Soliman et al. 2014) was observed.

It is widely known that the vanilla crop has low genetic variability due to the asexual propagation system to which it has been subjected for centuries, which limits the opportunity to have a genetically diverse germplasm bank that can be used in breeding programs to face the phytosanitary and production problems of this species (Soto Arenas and Cribb 2010). The fact of finding genetic variability during micropropagation could represent an alternative to broaden the genetic base in V. planifolia. Divakaran et al. 2015 and Ramírez-Mosqueda and Iglesias-Andreu 2015 reported that V. planifolia presents somaclonal variation during in vitro regeneration from callus. Divakaran et al. (2015) in callus regenerants indicated variations in morphology and 76.25% genetic polymorphism using RAPD profiles, while Ramírez-Mosqueda and Iglesias-Andreu (2015) using ISSR analyses on regenerated plantlets, revealed the existence of 71.66% polymorphism.

In conclusion, the subculture number affects somaclonal variation and in vitro development of V. planifolia. In our study, the polymorphism found after the fifth subculture in MS medium supplemented with 8.86 μM BAP suggests that it could be a promising breeding program system. If the objective is to maintain high genetic fidelity during its micropropagation, it is recommended to multiply an explant by no more than five subcultures. On the other hand, if the aim is to maximize the number of shoots per explant, it is recommended to carry out between five and ten subcultures, with the possibility of presenting high percentages of somaclonal variation. It is recommended that future reports of in vitro regeneration of plants on a commercial scale should indicate in which subculture, the experiment was carried out.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akdemir H, Suzerer V, Tilkat E, Onay A, Çiftçi YO. Detection of variation in long-term micropropagated mature pistachio via DNA-based molecular markers. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;180(7):1301–1312. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azman AS, Mhiri C, Grandbastien MA, Tam S. Transposable elements and the detection of somaclonal variation in plant tissue culture: a review. Malays Appl Biol. 2014;43(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Babu GA, Vinoth A, Ravindhran R. Direct shoot regeneration and genetic fidelity analysis in finger millet using ISSR markers. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018;132:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bairu MW, Fennell CW, Van Staden J. The effect of plant growth regulators on somaclonal variation in Cavendish banana (Musa AAA cv. ‘Zelig’) Sci Hortic. 2006;108(4):347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bairu MW, Aremu AO, Van Staden J. Somaclonal variation in plants: causes and detection methods. Plant Growth Regul. 2011;63(2):147–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Bello JJ, Iglesias-Andreu LG, Avilés-Vinas SA, Gómez-Uc E, Canto-Flick A, Santana-Buzzy N. Somaclonal variation in habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) as assessed ISSR molecular markers. HortScience. 2014;49(4):481–485. [Google Scholar]

- Bory S, Grisoni M, Duval MF, Besse P. Biodiversity and preservation of vanilla: present state of knowledge. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2008;55(4):551–571. [Google Scholar]

- Divakaran M, Babu KN, Ravindran PN, Peter KV. Biotechnology for micropropagation and enhancing variations in Vanilla. Asian J Plant Sci Res. 2015;5(2):52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Farahani F, Yari R, Masoud S. Somaclonal variation in Dezful cultivar of olive (Olea europaea subsp. europaea) Gene Conserve. 2011;10:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gantait S, Kundu S. In vitro biotechnological approaches on Vanilla planifolia Andrews: advancements and opportunities. Acta Physiol Plant. 2017;39(9):196. [Google Scholar]

- Gantait S, Mandal N, Bhattacharyya S, Das PK, Nandy S. Mass multiplication of Vanilla planifolia with pure genetic identity confirmed by ISSR. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;3:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Greule M, Tumino LD, Kronewald T, Hener U, Schleucher J, Mosandl A, Keppler F. Improved rapid authentication of vanillin using δ13C and δ2H values. Eur Food Res Technol. 2010;231(6):933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ř, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron. 2001;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jain SM. Tissue culture-derived variation in crop improvement. Euphytica. 2001;118(2):153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Jain SM, Brar DS, Ahloowalia BS, editors. Somaclonal variation and induced mutations in crop improvement. Berlin: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar K, Devi V, Sharma S, Soni M, Sharma D. Effect of physiological age and growth regulators on micropropagation of Aloe vera followed by genetic stability assessment. Nat Acad Sci Lett. 2015;38(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Saeed B, Kauser N. Establishment of genetic fidelity of in vitro raised banana plantlets. Pak J Bot. 2011;43(1):233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kılınç FM, Süzerer V, Çiftçi YÖ, Onay A, Yıldırım H, Uncuoğlu AA, Metin ÖK. Clonal micropropagation of Pistacia lentiscus L. and assessment of genetic stability using IRAP markers. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;75(1):75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna H, Alizadeh M, Singh D, Singh U, Chauhan N, Eftekhari M, Sadh RK. Somaclonal variations and their applications in horticultural crops improvement. 3 Biotech. 2016;6(1):54. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin PJ, Scowcroft WR. Somaclonal variation—a novel source of variability from cell cultures for plant improvement. Theor Appl Genet. 1981;60(4):197–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02342540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro-Castellanos JO, Mata-Rosas M, González D, Arias S, Reverchon F. In vitro propagation of endangered Mammillaria genus (Cactaceae) species and genetic stability assessment using SSR markers. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2018;54(5):518–529. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TSG. Micropropagation of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1987;10(1):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Espinosa HE, Murguía-González J, García-Rosas B, Córdova-Contreras AL, Laguna-Cerda A, Mijangos-Cortés JO, Santana-Buzzy N. In vitro clonal propagation of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia ‘Andrews’) HortScience. 2008;43(2):454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Mamedes-Rodrigues TC, Batista DS, Vieira NM, Matos EM, Fernandes D, Nunes-Nesi A, Cruz CD, Viccini LF, Nogueira FTS, Otoni WC. Regenerative potential, metabolic profile, and genetic stability of Brachypodium distachyon embryogeic calli as affected by successive subcultures. Protoplasma. 2018;255:655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00709-017-1177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Estrada E, Caamal-Velázquez JH, Salinas-Ruíz J, Bello-Bello JJ. Assessment of somaclonal variation during sugarcane micropropagation in temporary immersion bioreactors by intersimple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2017;53(6):553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes BMJ, Filippi SB, Demetrio CGB, Rodriguez APM. A statistical approach to study the dynamics of micropropagation rates, using banana (Musa spp.) as an example. Plant Cell Rep. 1999;18(12):967–971. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MP (1997) Tools for population genetic analyses (TFPGA) 1.3: a windows program for the analysis of allozyme and molecular population genetic data. Computer software distributed by author

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15(3):473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Zhang TT, Zhang J. Effect of subculture times on genetic fidelity, endogenous hormone level and pharmaceutical potential of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum callus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015;122(1):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Mosqueda MA, Iglesias-Andreu LG. Indirect organogenesis and assessment of somaclonal variation in plantlets of Vanilla planifolia Jacks. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015;123(3):657–664. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Castellá A, Iglesias-Andreu LG, Bello-Bello JJ. Improved propagation of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews) using a temporary immersion system. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2014;50(5):576–581. [Google Scholar]

- Rani V, Raina SN. Genetic fidelity of organized meristem-derived micropropagated plants: a critical reappraisal. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2000;36(5):319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MP, Sarla N, Siddiq EA. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica. 2002;128(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Rojas VM, Herrera-Cabrera BE, Delgado-Alvarado A, Soto-Hernández M, Castillo-González F, Cobos-Peralta M. Chemotypical variation in Vanilla planifolia Jack. (Orchidaceae) from the Puebla–Veracruz Totonacapan region. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59(5):875–887. [Google Scholar]

- Sales EK, Butardo NG. Molecular analysis of somaclonal variation in tissue culture derived bananas using MSAP and SSR markers. Int J Biol Vet Agric Food Eng. 2014;8(6):615–622. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman HIA, Metwali EMR, Almaghrabi OAH. Micropropagation of Stevia rebaudiana Betroni and assessment of genetic stability of in vitro regenerated plants using inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) marker. Plant Biotechnol. 2014;31(3):249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Soto Arenas MA, Cribb P. A new infrageneric classification and synopsis of the Genus Vanilla plum. ex mill. (Orchidaceae: Vanillinae) Lankesteriana. 2010;9:355–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar RV, Venkatachalam L, Bhagyalakshmi N. Genetic fidelity of long-term micropropagated shoot cultures of vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) as assessed by molecular markers. Biotechnol J. 2007;2(8):1007–1013. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CN, Via LE. A rapid CTAB DNA isolation technique useful for RAPD fingerprinting and other PCR applications. Biotechniques. 1993;14(5):748–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]