Abstract

Objective:

Pharmacological treatments for agitation and aggression in Alzheimer disease patients have shown limited efficacy. We assessed the heterogeneity of response to citalopram in order to identify individuals who may be helped or harmed.

Methods:

In this double-blinded, parallel-group multicenter trial of 186 patients with Alzheimer disease and clinically significant agitation, participants were randomized to citalopram or placebo for 9 weeks, with dose titrated to 30 mg/day over the first 3 weeks. We assessed 5 planned, potential predictors of treatment outcome; and 6, additional predictors. We then used a two-stage, multivariate method to select the most likely predictors; grouped participants into 10 subgroups by their index scores; and estimated the citalopram treatment effect for each.

Results:

Five covariates were likely predictors and treatment effect was heterogeneous across the subgroups. Patients for whom citalopram was more effective were more likely outpatients, least cognitively impaired (MMSE >=21), moderately agitated, and within the middle age range (76 to 82 years). Patients for whom placebo was more effective were more likely in long-term care, more severely cognitively impaired, had more severe agitation, and prescribed lorazepam.

Conclusions:

Considering several covariates together allowed the identification of responders. Those with moderate agitation and with relatively less cognitive impairment are more likely to benefit from citalopram; and those with more severe agitation and greater cognitive impairment are at greater risk for adverse responses. Considering the doses used and its association with cardiac QT prolongation as well, citalopram’s use to treat agitation may be limited to a subgroup of people with dementia.

Introduction

Aggression and agitation are frequent in people with dementia or Alzheimer disease. Agitation is generally multi-determined, may wax and wane, is often associated with psychosocial stress, disruption, inter-current medical conditions, and drug effects, and often can be managed by addressing the underlying conditions and without psychotropic medications.1,2 Aggression is associated with similar factors, often fluctuates, may be a response to perceived threat, but requires intervention when it causes patients to be a threat to their own and others’ well-being. In clinical practice a range of psychotropic drugs are often prescribed for agitation or aggression, antipsychotics most frequently, anxiolytics and antidepressants, less so.3 These medications have substantial limitations in terms of efficacy and safety.4

Antidepressants have been trialed for treating depression in people with dementia,5,6 and, more recently, for agitation.7 Citalopram, in particular, showed equivalence to antipsychotics for inpatients and outpatients but with differential adverse events.8,9 A recent, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed efficacy for citalopram for Alzheimer disease patients with agitation based on clinical global and agitation scale outcomes. As part of the statistical analysis plan, we report subgroup analyses that use a univariate method and a two-stage multivariate method10 to assess heterogeneity of response and possible predictors of differential responses between citalopram and placebo treatments.

Methods

The primary objective of the trial was to assess citalopram’s efficacy for agitation or aggression (see primary report and detailed methods).7,11 Participants had probable Alzheimer disease, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)12 scores from 5 to 28, and clinically significant agitation, for which a physician determined that medication would be appropriate based on scales ratings of either ‘very frequently’ (i.e., once or more per day), or ‘occurring frequently with moderate or marked severity’ (i.e., several times per week and difficult to redirect or control) on the agitation/aggression domain of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.13 They could not have had a major depressive episode or psychosis requiring antidepressant or antipsychotic treatment. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine at stable doses were allowed. Patients received a psychosocial intervention and were randomized to either citalopram (n = 94) or placebo (n = 92) for 9 weeks. Dosages were titrated to 30 mg per day over 3 weeks based on response and tolerability. Co-primary outcomes were the modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study – Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC),14 modified to assess agitation, and the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale.15 The 18-point Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale subscale consists of the agitation, hostility/uncooperativeness, and disinhibition items from the parent scale; each rated on a 0 to 6 scale as ‘not present,’ ‘very mild,’ ‘mild,’ ‘moderate,’ ‘moderately-severe,’ ‘severe,’ and ‘extremely severe.’ Other outcomes were scores from the short-form of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory,16 agitation/aggression subscale of the Neuropsychiatric inventory, 12-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living scale (ADL),17 the MMSE, and the use of lorazepam as a rescue medication.

Patients who were randomly assigned to citalopram (78% received 30 mg per day and 15% received 20 mg) were significantly improved compared with those who were assigned to placebo on both primary outcome measures. The Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale estimated treatment difference at week 9 (citalopram minus placebo) was −0.93 points (95%CI, −1.80 to −0.06), P = .04. Forty percent of the citalopram-treated group were rated as moderately or markedly improved on the CGIC compared with 26% of placebo recipients, a 14% absolute risk difference, and an estimated treatment effect (i.e., odds ratio (OR) of being at or better than a given CGIC category) of OR= 2.13 (95%CI, 1.23 to 3.69), P = .01. The citalopram-treated group also showed significant improvement on the short-form Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, 12-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory, and caregiver distress scores; but not on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory agitation subscale, ADLs, or in less use of lorazepam.7 Worsening of cognition as measured by the MMSE and electrocardiographic QT interval prolongation were seen in the citalopram group.7,18

The planned subgroup analyses reported here included the following 5 pre-specified baseline predictors: residency status (long-term care or outpatient), presence of psychosis (i.e., delusions or hallucinations as rated on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory), and severity of functional impairment (based on the ADL), cognitive impairment (MMSE), and agitation (Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale). We also selected 6 additional potential predictors of outcome: age, gender, and the use of memantine, lorazepam, trazodone, or cholinesterase inhibitors within three weeks of baseline. Each predictor was collapsed into 2 or 3 categories. The MMSE was divided into mild (≥21), moderate (11–20), and severe (≤ 10) cognitive impairment based on previous literature.19 Other continuous variables were categorized as tertiles.

Subgroup analyses were conducted using univariate and multivariate interaction methods. For the univariate interaction method, the treatment effect across categories of a predictor was compared using logistic regressions for CGIC response and for Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale response outcomes (i.e., odds ratio of a 50% reduction from baseline, citalopram versus placebo). The remaining continuous outcomes (ADL, MMSE, and Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory) were modeled using linear mixed-effects regression models which included a patient-specific random intercept, visit indicator, treatment indicator, treatment by visit interactions, and baseline outcome. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess significance of the treatment by covariate interactions in all models.

For the multivariate interaction method, a typical regression that includes multiple interactions relies heavily on model assumptions; therefore we used an exploratory post hoc, two-stage approach.10 Of the 11 baseline covariates, those for which there was a greater than 3-fold change in odds ratio between any two covariate levels were included in two-stage working models.

In the first stage, an index score was calculated for each participant based on the parametric working models using the baseline predictors. Specifically, for each participant, we used his or her baseline covariate values in the models to obtain a predicted response probability under citalopram and a predicted response probability under placebo. The index score was then calculated as the difference between the predicted response probabilities from the citalopram and placebo models, and represents the predicted treatment effect for that participant based on the working models (see appendix). Participants with the same index score can be thought of as a subset with that combination of covariate values. The value of the index score, however, is not necessarily an accurate estimate of the true treatment effect for that subset if the working models are incorrect.

The second stage of the analysis was conducted to allow for the possibility that the working models might be incorrect. In this stage, participants were sorted by index score and grouped into deciles; the treatment effect for each group was estimated non-parametrically as the difference between the empirical response-probability under citalopram minus placebo for that group. Confidence intervals for the subgroup treatment effect estimates were calculated by bootstrapping with a correction for multiple comparisons (see appendix).

Results

The covariates that were continuous measures, including age, ADCS-ADL scale, and Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, were divided into tertiles and were roughly balanced between randomized arms. Some of the categorical covariates were not evenly distributed in the trials sample: 7% lived in long-term care; 48% had delusions or hallucinations; 54% were male, and 69%, 42%, 10%, and 8% were prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, trazodone, and lorazepam, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of planned and post hoc baseline predictors

| Total | Citalopram | Placebo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Randomized | 186 | 94 | 92 | |||

| Residence | ||||||

| Home or relative | 173 | (93%) | 86 | (91%) | 87 | (95%) |

| Long term care | 13 | (7%) | 8 | (9%) | 5 | (5%) |

| Psychosis (Neuropsychiatric Inventory items 1 and 2) | ||||||

| No hallucinations or delusions | 97 | (52%) | 52 | (55%) | 45 | (49%) |

| Hallucinations and/or delusions | 89 | (48%) | 42 | (45%) | 47 | (51%) |

| ADCS - Activities of Daily Living (ADL) | ||||||

| Largest tertile: 54+ | 65 | (35%) | 39 | (41%) | 26 | (28%) |

| Second tertile: 31–53 | 64 | (34%) | 28 | (30%) | 36 | (39%) |

| Lowest tertile: 0–30 | 57 | (31%) | 27 | (29%) | 30 | (33%) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | ||||||

| Mild to no impairment: 21+ | 54 | (29%) | 32 | (34%) | 22 | (24%) |

| Moderate: 11–20 | 81 | (44%) | 45 | (48%) | 36 | (39%) |

| Severe: 0–10 | 51 | (27%) | 17 | (18%) | 34 | (37%) |

| Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscore | ||||||

| Lowest tertile: 0–5 | 52 | (28%) | 29 | (31%) | 23 | (25%) |

| Middle tertile: 6–8 | 60 | (32%) | 34 | (36%) | 26 | (28%) |

| Highest tertile: 9+ | 74 | (40%) | 31 | (33%) | 43 | (47%) |

| Age | ||||||

| 47–75, years | 57 | (31%) | 30 | (32%) | 27 | (29%) |

| 76–82 | 60 | (32%) | 29 | (31%) | 31 | (34%) |

| 83–92 | 69 | (37%) | 35 | (37%) | 34 | (37%) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 101 | (54%) | 50 | (53%) | 51 | (55%) |

| Female | 85 | (46%) | 44 | (47%) | 41 | (45%) |

| Memantine | ||||||

| No memantine | 108 | (58%) | 53 | (56%) | 55 | (60%) |

| Memantine | 78 | (42%) | 41 | (44%) | 37 | (40%) |

| Lorazepam | ||||||

| No lorazepam | 171 | (92%) | 88 | (94%) | 83 | (90%) |

| Lorazepam | 15 | (8%) | 6 | (6%) | 9 | (10%) |

| Trazodone | ||||||

| No trazodone | 167 | (90%) | 83 | (88%) | 84 | (91%) |

| Trazodone | 19 | (10%) | 11 | (12%) | 8 | (9%) |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | ||||||

| No cholinesterase inhibitors | 58 | (31%) | 32 | (34%) | 26 | (28%) |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor(s) | 128 | (69%) | 62 | (66%) | 66 | (72%) |

Based on the univariate method, the effect of citalopram versus placebo on CGIC response did not vary significantly between levels of any of the 5 planned and 6 post hoc predictors except for residence status: patients living at home or with relatives experienced a significantly greater citalopram effect versus placebo than patients in long-term care (LR= 2.28 (95% CI, 1.14 to 4.57) and LR= 0.11 (95% CI, 0.01 to 1.78), respectively, P= .025; Figure 1). Moreover, using the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, ADL, Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, and MMSE as response outcomes resulted in no significant interactions on any of the 11 candidate predictors of response except for age with the CMAI (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study- Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) response for pre-specified and post hoc subsets The first five were pre-specified and the next six were post hoc (see accompanying file).

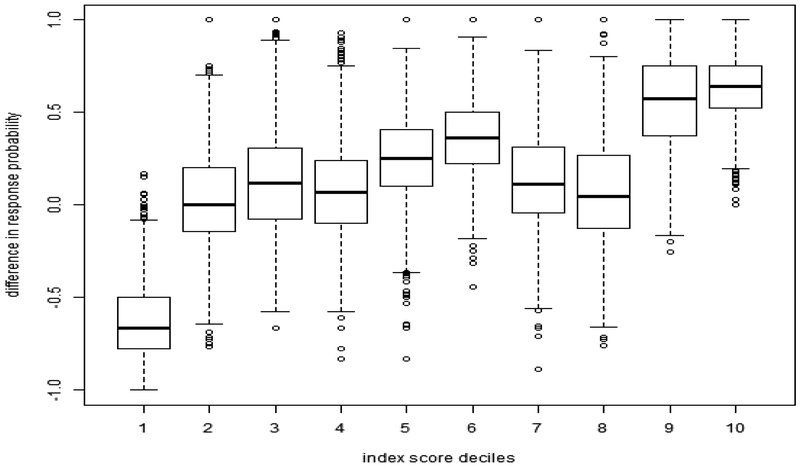

For the multivariate method, we assessed heterogeneity of the treatment effect using two-stages. For CGIC, 5 of the 11 baseline covariates met the selection criteria: residency, MMSE, Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, age, and lorazepam use, and were used to compute the index score (see appendix). The variation of the treatment effect across groups of different index scores is shown in Figure 2. The figure demonstrates as well that there is a subgroup of patients, namely with index scores below the 62 percentile, for whom there is 95% confidence that the treatment effect is at least as large as the estimated average effect for all patients.

Figure 2. The average difference in CGIC response probability and its 95% confidence interval between citalopram and placebo.

(95% CI after correcting for multiple comparisons “looks”) For more than 62% of the patients the 95% confidence interval was larger than the average 0.136 (seen at 100% on the x axis). This can be interpreted clinically by viewing the distribution of covariates for these patients (see Table 2) and comparing this to the distribution of all patients. For example, for a given value on the x axis, e.g., 86%ile, the corresponding value on the y axis, y=0.25, is the difference between the percent response under citalopram minus percent response under placebo (estimated nonparametrically) for the patients with the index scores below the 86%ile.

This can be interpreted clinically by viewing the distribution of covariates for participants with different index score categories compared to the distribution of all patients (Figure 3 and Table 2). Figure 3 shows the nonparametrically estimated effect for patient groups combined by the deciles of the index score. A likelihood ratio test comparing the 10 deciles to a hypothesis that there is no heterogeneity suggested that the treatment effect truly varies by index score subgroups (P=.002). This 10-mean model can be further reduced to a 3-mean model of negative or placebo responders (decile 1), marginal or low responders (deciles 2 to 8), and high responders (deciles 9 and 10) which was still a significant improvement over the common mean model, but was not different from the 10-mean model (P= .984).

Figure 3. Box plots of the index score deciles (CGIC).

The figure shows that 2 groups, deciles 9 and 10, show particularly strong effects favoring citalopram response compared to placebo, and one group, decile 1, shows a strong effect favoring placebo as more effective than citalopram. Most groups show essentially trivial effects on average for citalopram response.

Table 2.

Table of covariate distributions for all participants, and for groups defined by the working model score, including the 3 significant subset deciles – decile 1 favoring placebo and deciles 9 and 10 favoring citalopram – and the top 60% index scorers (see Figure 3)

| Covariates | All participants | decile 1 | top 60% index scorers | decile 9 | decile 10 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Home, outpatient | 155 | (93%) | 10 | (48%) | 100 | (100%) | 15 | (100%) | 17 | (100%) |

| Long term care | 12 | (7%) | 11 | (52%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Mini-mental State Examination | ||||||||||

| Mild impairment, 21+ | 49 | (29%) | 3 | (14%) | 38 | (38%) | 6 | (40%) | 17 | (100%) |

| Moderate 11–20 | 75 | (45%) | 11 | (52%) | 36 | (36%) | 6 | (40%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Severe, 0–10 | 43 | (26%) | 7 | (33%) | 26 | (26%) | 3 | (20%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Neurobehavioral Rating Scale | ||||||||||

| Lowest tertile, 0–5 | 48 | (29%) | 5 | (24%) | 10 | (10%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Middle tertile, 6–8 | 55 | (33%) | 1 | (5%) | 51 | (51%) | 9 | (60%) | 17 | (100%) |

| Highest tertile, 9+ | 64 | (38%) | 15 | (71%) | 39 | (39%) | 6 | (40%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 47–75 years | 54 | (32%) | 10 | (48%) | 23 | (23%) | 0 | (0%) | 6 | (35%) |

| 76–82 | 53 | (32%) | 3 | (14%) | 40 | (40%) | 13 | (87%) | 8 | (47%) |

| 83–92 | 60 | (36%) | 8 | (38%) | 37 | (37%) | 2 | (13%) | 3 | (18%) |

| Lorazepam use | ||||||||||

| Non-user | 156 | (93%) | 14 | (67%) | 99 | (99%) | 15 | (100%) | 17 | (100%) |

| User | 11 | (7%) | 7 | (33%) | 1 | (1%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) |

Patients with the largest predicted treatment effects favoring citalopram were more likely to be living outside long-term care facilities, have milder cognitive impairment (MMSE, 21 to 28), a middle level of baseline agitation (Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, 6 to 8), be within the middle age range of the trials population (76 to 82 years), and not using lorazepam within three weeks of baseline. By comparison, patients with the largest predicted treatment effect favoring placebo were more likely to be living in long-term care, show moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE, ≤ 20), more severe baseline agitation (Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, 9 to 14), be within the youngest (47 to 75 years) or oldest age range (83 to 92), and use of lorazepam. When using the above two-stage method for the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale response and the secondary outcomes, there was no analogous evidence of heterogeneity across index scores.

Discussion

Given the clinical heterogeneity of agitation and aggression in patients with Alzheimer disease it is likely that any effective therapy would benefit only a subset of patients with these behaviors. Yet, in our planned, protocol-specified, analysis of this randomized, controlled trial we found no individual covariates that predicted positive outcomes with citalopram, but did find that residence in long-term care was associated with a negative outcome with citalopram.

Thus we hypothesized incorrectly that subgroups defined by single covariate predictors would respond differentially to citalopram. This failure could be a result of small sample size, imbalances in the actual outcomes associated with the covariates, and the overall small statistical effect sizes of the clinical outcomes of the trial. For example, only 186 participants were randomly assigned to treatment, 7% were living in nursing homes, 7% were taking lorazepam at baseline, and the statistically significant co-primary outcomes were a relatively small 0.136 risk difference for the CGIC and less than 1 point difference on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale between citalopram and placebo. Thus, differences in the single covariate-defined subgroups would have been difficult to discern or potentially unreliable at identifying study participants who may have benefited from citalopram.

The multivariate analysis, on the other hand, confirmed the main outcome of the trial, that there was an average treatment effect or difference in response probability with citalopram treatment, i.e., citalopram improved CGIC response compared to placebo by an average 13.6% difference in response probability (citalopram – placebo). Secondly, and importantly, this analysis identified subgroups for which the treatment effects were larger or smaller than the average, i.e., the treatment effect for citalopram compared with placebo was not homogeneous across participants.

Indeed, two groups (about 20% of the sample) showed particularly large effects with differences in response probabilities for citalopram compared to placebo of approximately 60 to 70%; one group (about 10% of the sample) showed a large negative effect with a difference in response probability of approximately 70% favoring placebo; while the other groups (about 70%) showed essentially trivial effects. The clinical characteristics of the two subgroups for which citalopram was most effective included outpatient status, milder cognitive impairment, ‘moderate’ to ‘moderately-severe’ agitation scores as described by the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale (as compared with ‘mild’ to ‘moderate’ for the lowest tertile and ‘moderately-severe’ to ‘severe’ Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale descriptors for the highest tertile), and being neither too young nor too old in age.

The characteristics of the subgroup for which assignment to placebo was most effective were residence in long-term care, being within the oldest or youngest age ranges (i.e., ages 83–92 or 47–75 years), having moderate to severe cognitive impairment, i.e., MMSE <=20, ‘moderately-severe’ to ‘severe’ agitation on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale, and the use of lorazepam.

The identification of a subgroup that had markedly better outcomes on placebo suggests that the more severely agitated and cognitively impaired might be harmed by citalopram. Thus the groups most responsive to citalopram were more mildly cognitively impaired and less severely agitated prior to randomized treatment.

Clinical trials usually can address only one clinical hypothesis with reasonable statistical power. The results of the multivariable post hoc analysis reported here highlight the limitations of limiting post hoc analyses to univariable methods, a characteristic of many trials including this one. Allowing the inclusion of patients with a broad range of agitation and cognitive impairment may have led to outcomes that are difficult to apply to clinical practice: On average, patients enrolled in CitAD benefitted from citalopram but some benefitted more than others in a manner that was not random and not predicted. Here, our two-stage multivariate analysis suggested clinical implications and a way forward (see below).Limitations of the trial, analysis, and statistical methods included the small sample size and our knowledge of the results of the pre-specified univariate analyses, because this informed the subsequent multivariate analysis. Importantly, the predictive covariates for composing the subgroups were chosen primarily because they were relatively stable baseline characteristics and because there were limited candidate predictors from which to choose. Since covariates that are predictive for treatment differences (i.e., in our analysis those with a 3-fold change in odds ratio) may both interact with the treatment assignment and relate to the outcome in either treatment group, it is possible that our model is misspecified, or that interactions are not be well defined, factors limiting the ability to make inferences about treatment effects. Ultimately, however, the validity of the interpretation of the results derives from the empirical effect sizes in the subgroups and does not depend on the selection criteria.

Although a statistically significant treatment interaction was detected only for residence using the univariate method, the direction of the (nonsignificant) interactions was the same for both methods for all the subgroups included in the multivariate model. However, the empirical basis of the proposed multivariate approach, as compared to other, more model-dependent approaches, make the interpretation of the results more reliable.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results support heterogeneity of clinical response to citalopram, specifically that outpatients with Alzheimer disease without severe agitation, who do not have major depression or psychosis for which antipsychotics may be required, may benefit from citalopram compared to placebo. Future trials of citalopram or similar drugs used for the purpose might account for this heterogeneity by stratifying or including or excluding participants based on levels of cognitive impairment and severity of agitation. Although the small numbers within the decile group may not broadly inform the use of citalopram in long-term care or with patients taking lorazepam, nonetheless it may be prudent to avoid citalopram under these circumstances, and especially when there are other options. The finding that those with more severe agitation or aggression responded better with placebo or poorly with citalopram raises further caution. Given these results, the established associations with delayed cardiac repolarization (including the last 48 participants in this study18 and assessments by the FDA),18,20 with cognitive impairment,7 safety concerns of antidepressants for depressed elderly,21 the FDA’s recommendation to avoid citalopram doses of 30 mg per day, citalopram may have limited use for treating agitation in Alzheimer disease.

In sum, these analyses demonstrate that citalopram’s effect, at 30 mg per day, is heterogeneous with maximal salutary effects for patients with relatively milder cognitive impairment and moderate agitation, and is without effect or potentially harmful for patients with more moderate to severe cognitive impairment and more severe agitation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Grant funding: National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Mental Health, R01AG031348 and in part by NIH P50 AG05142 (USC, LSS).

Disclosures

LSS: Dr. Schneider reports, from 3 years prior to and during the course of this study, receipt of grants and clinical trials support from NIH, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche; paid consultancy, including data monitoring committees, adjudication committees, for Abbott, Abbvie, AC Immune, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bristol Myers Squibb, Elan, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Forum, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Merz, Novartis, Orion, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Takeda, Toyama/FujiFilm, Zinfandel.

CF: none

LTD: none

DPD: Advisory boards for Abbvie and Lundbeck.

CAM: none

CMM: Dr. Marano has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health

JAN: none

BGP: Dr Pollock reports receipt of a grant to his institution from NIA and NIMH; board membership with Lundbeck Canada; a paid consultancy with Wyeth; and receipt of travel and accommodation expenses from Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foundation.

APP: Dr Porsteinsson reports receipt of a grant to his institution from AstraZeneca, Avanir, Baxter, Biogen, BMS, Eisai, Elan, EnVivo, Genentech/Roche, Janssen Alzheimer Initiative, Medivation, Merck, Pfizer, Toyama, Transition Therapeutics, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the Department of Defense; paid consultancy for Elan, Janssen Alzheimer Initiative, Lundbeck, Pfizer, and TransTech Pharma; membership on data safety and monitoring boards for Quintiles, Functional Neuromodulation, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute; participation on a speaker’s bureau for Forest; and development of educational presentations for CME Inc and PRI.

PVR: Legal testimony for Janssen.

LR: none

PBR: Grant support (research or CME) from Merck, Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Elan, Functional Neuromodulation, AFAR, and NIA, and has served as consultant for Janssen, Abbvie, Lundbeck, and Pfizer. He has been reimbursed for CME development by Vindico, and received travel support from Avanir.

DS: none

DW: Dr. Weintraub has received research funding from Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, National Institutes of Health, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; honoraria from Biotie, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck Inc., Acadia, UCB, Clintrex LLC, Medivation, CHDI Foundation, and the Weston Foundation; license fee payments from the University of Pennsylvania for the QUIP and QUIP-RS; royalties from Wolters Kluweland; and fees for testifying in two court cases related to impulse controls disorders in Parkinson’s disease (March, 2013-April, 2014, payments by Eversheds and Roach, Brown, McCarthy & Gruber, P.C.).

CGL: Grant support (research or CME): NIMH, NIA, Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore, Weinberg Foundation, Forest, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Eisai, Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Lilly, Ortho-McNeil, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, National Football League, Elan, Functional Neuromodulation. Payment as consultant or advisor: Astra-Zeneca, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Eisai, Novartis, Forest, Supernus, Adlyfe, Takeda, Wyeth, Lundbeck, Merz, Lilly, Pfizer, Genentech, Elan, NFL Players Association, NFL Benefits Office, Avanir, Zinfandel, BMS, Abvie, Janssen, Orion, Otsuka, Servier, Astellas. Honorarium or travel support: Pfizer, Forest, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Health Monitor

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00898807

References

- 1.Aalten P, de Vugt ME, Jaspers N, Jolles J, Verhey FRJ. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Part I: findings from the two-year longitudinal Maasbed study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2013;9(5):602–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, et al. Trends in Antipsychotic Use in Dementia 1999–2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and Adverse Effects of Atypical Antipsychotics for Dementia: Meta-analysis of Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006;14(3):191–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, et al. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):136–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodaty H Antidepressant treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet.378(9789):375–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, et al. Effect of citalopram on agitation in alzheimer disease: The citad randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. A double-blind comparison of citalopram and risperidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(11):942–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai T, Tian L, Wong PH, Wei LJ. Analysis of randomized comparative clinical trial data for personalized treatment selections. Biostatistics. 2011;12(2):270–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drye LT, Ismail Z, Porsteinsson AP, et al. Citalopram for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: design and methods. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2012;8(2):121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, et al. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin HS, High WM, Goethe KE, et al. The neurobehavioural rating scale: assessment of the behavioural sequelae of head injury by the clinician. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1987;50(2):183–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Koroknay V, Braun J. The impact of a restraint-reduction program on nursing home residents: Physical restraints may be successfully removed with no adverse effects, so long as less restrictive and more dignified care is provided. Geriatric Nursing. 1994;15(3):142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 1997;11:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drye LT, Spragg D, Devanand DP, et al. Changes in QTc Interval in the Citalopram for Agitation in Alzheimer’s Disease (CitAD) Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e98426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance 217 (Review of NICE technology appraisal guidance 111). 2011; http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13419/53619/53619.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2012, 2012.

- 20.FDA Drug Safety Communication: Revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses [3-28-12]. US Food and Drug Administration; 2012; http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391.htm. Accessed June 30, 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. Bmj. 2011;343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.