Abstract

Recovery capital—the quantity and quality of internal and external resources to initiate and maintain recovery—is explored with suggestions for how recovery support services (RSS) (nontraditional, and often nonprofessional support) can be utilized within a context of comprehensive addiction services. This article includes a brief history of RSS, conceptual and operational definitions of RSS, a framework for evaluating RSS, along with a review of recent empirical evidence that suggests that rather than enabling continued addiction, recovery supports are effective at engaging people into care, especially those who have little recovery capital, and/or who otherwise would likely have little to no “access to recovery.”

Keywords: Recovery support services, recovery capital, peer support, access to recovery

“You need a little love in your life and some food in your stomach before you can hold still for some damn fool’s lecture about how to behave.”

–Billie Holiday

The sentiment above, expressed by a woman whose unparalleled musical talents, daring, and accomplishments were ended prematurely by a heroin overdose, is becoming increasingly accepted within some quarters of the addiction field. Rather than viewing “hitting bottom” as the necessary prerequisite for abstinence, this emerging view stipulates that at least some “recovery capital” is required for people to undertake the difficult and prolonged “work of recovery” (Davidson & Strauss, 1992; White, 1998; White, Boyle, & Loveland, 2003, 2004; White & Godley, 2003). By recovery capital, proponents of this approach refer to “the quantity and quality of internal and external resources that one can bring to bear on the initiation and maintenance of recovery from a life-changing disorder” (Granfield & Cloud, 1999, p. 3). In addition to financial, material, and instrumental resources (e.g., “some food in your stomach”), recovery capital includes such things as having a sense of belonging within a community of peers and supportive relationships with caring others (e.g., the “love in your life”).

This concept of recovery capital has shown particular promise in helping to account for why just as many, if not more, people appear to be able to achieve “natural recovery” (i.e., 50%–75% cease problematic use with little or no formal intervention; Dawson, 1996; Klingeman & Sobbell, 2001; Sobell, Cunningham, & Sobell, 1996; Toneatto, Sobell, Sobell, & Rubel, 1999; Waldorf, Reinarman, & Murphy, 1991) as those who appear to achieve successful drug use outcomes as a benefit of addiction treatment (57%), leaving a large percentage of people (i.e., 43%) who do not appear to respond to what are considered effective treatments (Prendergast, Podus, Chang, & Urada, 2002). The basic hypothesis, as Holiday poignantly stated, is that though people who already have recovery capital may either recover on their own or with formal help, those who have lost, or who never really had, adequate recovery capital will first have to acquire some amount of internal and external resources before being able to take up the challenge of recovery in a fully effective and sustained way. At its extreme, “losing everything” may leave the person not only without a foundation upon which to base his or her recovery, but also with nothing further left to lose. At times described as people with “refractory” addictions or as “unresponsive” to treatment (or castigated with such stigma-laden labels as “frequent flyers” or “retreads”), such individuals may perhaps be better understood as being in need, not of more addiction-related losses in their lives (their capacities for such pain are often immeasurable), but of additional recovery capital. Put simply, the major obstacle to recovery may be more the absence of hope than the absence of pain.

When phrased in this way, it is easy to see how efforts to increase a person’s recovery capital might be viewed as “enabling” in the eyes of some long-term veterans of addiction and addiction treatment. Why provide a person with an active addiction with resources (e.g., money) if he or she will only spend it on his or her drug(s) of choice? Why house someone if he or she will continue to use and therefore only be evicted once again? If people are protected from suffering the natural consequences of their poor choices they will never have reason to choose differently. Even in relation to such internal resources as self-esteem, a sense of confidence and efficacy, or a sense of belonging, how can people regain these assets when they continue to use? As long as their addiction remains active, are they not doomed to continued failure and rejection?

It is based on these kinds of considerations that the emerging technology of “recovery support services” is being met with some skepticism within the field. Although the brief history that follows suggests that this technology has been around in one form or another at least since the mid 19th century, empirical support has only begun to appear over the last decade (e.g., Berkman & Wechsberg, 2007; McLellan et al., 1994; McLellan et al., 1998). Recovery support services are now becoming increasingly visible through the federal Center for Substance Abuse Treatment’s Recovery Community Support Program and its recent $300 million Access to Recovery initiative; a voucher-based initiative in which people with addictions are able to choose the services they wish to receive, including a range of nonclinical recovery support services (White, 1998, 2001). States that have received Access to Recovery funds are seeing the development of an increasing array of recovery supports, as well as an increasing sense of legitimacy for supports that have been provided in the past outside of the formal addiction treatment system. Many of these supports are provided by programs staffed and run by people in recovery, whereas others are provided by faith-based agencies. Although there is no reason to think that recovery support services could not be provided effectively by people or agencies who are neither peers nor faith based, the entry of such programs, which typically are led by nonprofessionals, into the more formal network of addiction treatment agencies, which typically are led by professionals, has added to the skepticism in the field surrounding this alternative form of service delivery.

This article provides an introduction to the topic, approach, and role of recovery support services in recovery and within a comprehensive network of addiction services and supports. We begin with a statement of the rationale for such services and then offer a brief history of the use of various forms of recovery support services within the addiction community before turning to a conceptual and operational definition of how precisely these supports differ from other services. We then review the empirical evidence that is beginning to accumulate which argues for the utility of these supports for certain functions and for certain people at certain times in the recovery process. We conclude that the data collected thus far suggests that, rather than enabling continued addiction, recovery supports are effective at engaging people into care, especially those who have comorbid conditions, who appear to have little recovery capital, and/or who otherwise would likely have little to no “access to recovery.”

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

At the present time, only 10% of U.S. citizens meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for substance abuse or dependence receive specialty addiction treatment each year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2003), and only 25% will receive an episode of such care in their lifetime (Dawson et al., 2005). Despite notable heterogeneity in outcome studies, meta-analyses have shown that, on average, 57% of those adults who do access specialty addiction treatment will experience reduced drug use (Brewer, Catalano, Haggerty, Gainey, & Fleming, 1998; Griffith, Rowan-Szal, Roark, & Simpson, 2000; Marsh, D’Aunno, & Smith, 2000; Prendergast, Podus, & Chang, 2000; Prendergast et al., 2002; Stanton & Shadish, 1997). Although this percentage may initially seem impressive, it becomes less so when compared to the 50% to 75% of adults with addictions who achieve “natural recovery” (i.e., the cessation of problematic use without formal intervention).

Furthermore, research on addiction treatment also has shown consistently that roughly 50% of adults who receive addiction treatment resume their drug use within 6 months of ending treatment, regardless of their substance of choice (Anglin, Hser, & Grella, 1997; Institute of Medicine, 1998; McKay et al., 1999; McKay et al., 2004), with many of these individuals relapsing within 90 days of discharge (Hubbard, Flynn, Craddock, & Fletcher, 2001). Although longer treatment episodes, especially residential treatment, and posttreatment continuing care are associated with better outcome at 5-year follow-up (Hubbard, Craddock, & Anderson, 2003; Ray, Weisner, & Mertens, 2005; Ritsher, McKellar, Finney, Otilingam, & Moos, 2002), the last decade has seen a significant shift toward briefer and briefer treatment and away from residential settings to out-patient care, where nearly 90% of addiction treatment now occurs (McLellan, Carise, & Kleber, 2003; SAMHSA, 2002a).

Among those individuals who do access care, one of the major barriers they face to benefiting from effective treatment is retention. Depending on the service setting, between one half and two thirds of people drop out of treatment or are administratively discharged before successful treatment completion (Simpson, Joe, & Brown, 1997; Simpson, Joe, & Rowan-Szal, 1997; Stark, 1992); numbers that are even worse among racial and ethnic minority populations (McCaul, Svikis, & Monroe, 2001; Milligan, Nich, & Carroll, 2004; Siqueland, Crits-Christoph, Gallop, Barber, et al., 2002; Siqueland, Crits-Christoph, Gallop, Gastfriend, et al., 2002; Wells, Klap, Koike, & Sherbourne, 2001). Finally, approximately one half of all adults with addictions have a cooccurring psychiatric illness (Kessler et al., 1997; Kessler et al., 1996; Reiger et al., 1990). Among those individuals who have substance dependence and serious mental illness, only 19% receive treatment for both disorders. and 29% receive no treatment at all (SAMHSA, 2002b). For those with dependence and less severe mental illnesses, only 4% receive services for both conditions, and 71% receive no treatment (Watkins, Burnam, Kung, & Paddock, 2001). Despite ample evidence of the crucial role integrated mental health and addiction treatment play in short- and long-term outcomes for adults with co-occurring disorders (Friedmann, Hendrickson, Gerstein, Dean, & Zhang, 2004; Marsh, Cao, & D’Aunno, 2004; Smith & Marsh, 2002), only one half of all residential and outpatient settings offer specialized services for people with co-occurring disorders (Mojtabai, 2004). Clearly there is room for improvement in terms of increasing the responsiveness and effectiveness of addiction care.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Among the variety of recovery support services, those provided by people in their own recovery from addiction and those provided by faith-based communities have been the most prevalent and/or well documented over the previous 150 years. Addiction recovery mutual aid societies, for example, have a rich history spanning 18th- and 19th-century Native American “recovery circles” (abstinence-based healing and religious/cultural revitalization movements), the Washingtonians (1840s), fraternal temperance societies (1840s–1870s), ribbon reform clubs (1870s–1890s), Drunkard’s Club (1870s), United Order of Ex-Boozers (1914), Alcoholics Anonymous (AA; 1935), Alcoholics Victorious (1948), Narcotics Anonymous (1953) and other Twelve-Step adaptations, adjuncts to AA (Calix Society, Jewish Alcoholics, Chemically dependent persons, and significant others (JACS)), alternatives to AA (e.g., Women for Sobriety, Secular Organization for Sobriety, LifeRing Secular Recovery), the Wellbriety Movement in Indian Country, and faith-based recovery ministries (particularly within African American communities) (Coyhis & White, 2006; Sanders, 2002; White, 1998, 2001).

Peer-based social support linked to addiction treatment institutions span patient clubs developed within inebriate homes and asylums (Ollapod Club, the Godwin Associations) and addiction cure institutes (Keeley Leagues) (1860s–1890s), the Jacoby Club of the Emmanuel Clinic in Boston (1910), AA “wards” (in hospitals) and “farms” (1940s–1950s), halfway houses (1950s) and self-managed recovery homes (e.g., Oxford Houses), treatment program volunteers, California’s “social model” programs,1 treatment center “alumni associations,” to some of the new peer-based support models developed by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment’s Recovery Community Support Program grantees (White, 1998, 2001).

Street outreach to persons with addictions has been practiced under various guises for many years, from Victorian-era individuals in recovery from alcoholism who roamed urban slums and police courts looking for men who could benefit from their message of salvation and the resources of jobs and housing at their disposal (Boyer, 1978), to AA-sponsored efforts, to needle exchange programs and other contemporary forms of harm reduction (Thompson et al., 1998). The use of paid peer helpers (people in recovery hired to serve as guides for others seeking recovery) in the addictions arena more broadly spans recovered and recovering people working as temperance missionaries (1840s–1890s); aides (“jag bosses”) and managers of inebriate homes (1860s–1900); Keeley Institute physicians (1890–1920); “friendly visitors” within the Emmanuel Clinic in Boston (1906); lay alcoholism psychotherapists (1912–1940s); managers of “AA farms” and “AA rest homes” (1940s–1950s); halfway house managers (1950s); “para-professional” alcoholism counselors and professional “ex-addicts” (1960s–1970s); credentialed addiction counselors; detox technicians, residential aids, outreach workers, and case managers (1970s–1990s), to, more recently, “recovery coaches,” “recovery mentors,” and “recovery support specialists” (White, 1998, 2000b). There are several states (e.g., Connecticut, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Florida) that are working to systematically include peer-based recovery supports as part of a reconfigured continuum of addiction care, and several of these states are in the process of credentialing recovery support specialists to legitimize and formalize, and eventually increase the resource base for, this service.

Conceptual and Operational Definition

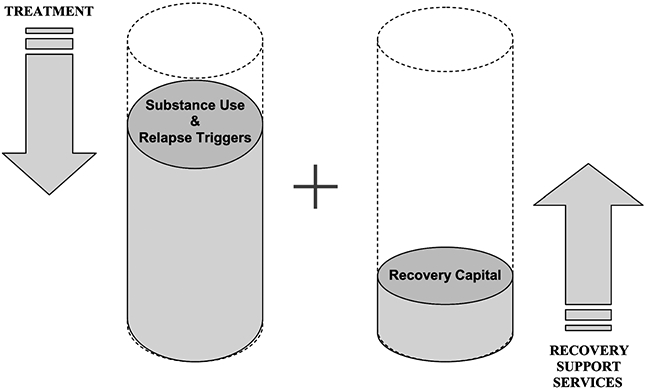

We conceptualize the relationship between addiction treatment and recovery supports as complimentary in nature, as depicted in Figure 1. The primary function and aim of treatment is biopsychosocial stabilization and recovery initiation by decreasing the person’s use and his or her vulnerability to internal and external relapse triggers. The primary function and aim of recovery supports is to help each individual move through recovery initiation to stable recovery maintenance by progressively increasing the person’s recovery capital. These functions and aims are not mutually exclusive, but overlap and may be pursued concurrently. In fact, some more recent advances, such as motivational interviewing (e.g., Miller & Rollnick, 1991) and contingency management (e.g., Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006; Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006) interventions, may represent a blending of the two approaches within one service, program, or relationship. There is no reason in principle why agencies, programs, and practitioners who provide treatment cannot also offer recovery supports, and vice versa. Although typically there are differences in these domains (with treatment most often being provided by professionals and recovery supports most often being provided by peers), the most important distinction between these complimentary approaches is in terms of their aims and functions.

FIGURE 1.

Respective roles of treatment and recovery support services.

How does one go about enhancing a person’s recovery capital? There may be as many ways of doing so as there are components to recovery capital, but the primary ways in which this is being done are finite and focused. The strategies of outreach/engagement and community-based case management have been borrowed from work with people who are homeless and/or who have serious mental illnesses. These strategies aim to connect the person to the financial, material, and instrumental resources he or she may need to address his or her basic needs for food, shelter, income, and clothing. Additional instrumental resources may be provided in the form of transportation to and from clinical and recovery support services and recovery-oriented, community activities, as well as child care to enable parents to participate in any of these activities. Finally, housing and housing supports may include such options as transitional and/or supported housing, liaison services with private landlords, and a rapidly growing network of self-managed recovery homes (Jason, Davis, Ferrari, & Bishop, 2001).

In terms of internal resources, recovery support services can offer positive role models of recovery as well as ongoing “coaching” or “mentoring,” thus enhancing hope/motivation and problem-solving skills. Other internal resources, such as a sense of confidence and efficacy, can be promoted through the use of strengths-based approaches in which people are assisted in identifying their own interests, assets, and goals and then connected to and supported in pursuing involvement in the meaningful activities of their choosing (e.g., Rapp, 1998). Face-to-face and telephone contact can be offered to assist people early in recovery to establish and/or maintain engagement in treatment and other recovery support services. And finally, supported employment, supported education and social support community engagement services, such as recovery community centers, like those being established in Connecticut and Vermont (White & Kurtz, 2005, 2006), and recovery industries (work co-ops such as Atlanta’s Recovery at Work) assist persons in recovery to build positive community connections, discover positive interests, take on valued social roles, and give back to their local communities. All of these activities constitute a form of recovery “priming”: modeling, encouraging, supporting, coaching, and advocating. A selected list of recovery support services is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

A Selective List of Recovery Support Services

| • Recovery mentoring, guiding or coaching, including case management and assistance with addressing basic needs |

| • Transportation to and from clinical, rehabilitative, and other recovery-oriented, community-focused activities |

| • Childcare provided to enable people to participate in treatment and in other services |

| • Sober and supported housing options such as transitional housing, recovery houses, liaison with private landlords, security deposits, etc. |

| • Pre-treatment engagement and post-treatment monitoring and support designed to assist people in establishing and/or maintaining engagement in other services and in positive vocational, educational, and social activities |

| • Social support and community engagement services, such as recovery community centers, mutual support, or recovery groups designed to assist persons to build positive community connections, discover positive personal interests, give back, and take on valued social roles |

| • Educational/vocational supports |

| • Legal services and advocacy |

In addition to being described as increasing a person’s recovery capital, recovery support services can thus be characterized as assisting people to (1) establish and maintain environments supportive of recovery; (2) remove personal and environmental obstacles to recovery; (3) enhance linkage to, identification with, and participation in local communities of recovery; and (4) increase the hope, inspiration, motivation, confidence, efficacy, social connections, and skills needed to initiate and maintain the difficult and prolonged work of recovery. As indicated above, there is a considerable range and diversity in the type of supports provided and the types of people who provide them, with different supports needed by different people and also perhaps by the same person at different times in his or her recovery. Outreach and engagement early in recovery may be replaced by recovery mentoring once the person is adequately engaged, just as sober housing may need to precede a person’s involvement in treatment or in educational or vocational activities. As one guiding principle, the more recovery capital a person has at any given time, the less likely he or she will be to need recovery supports. On the other hand, preliminary experience suggests that for many people who do need recovery supports, this need may be long term and may span the periods of prerecovery engagement, recovery initiation, recovery stabilization, and recovery maintenance. As such, the service relationships involved in recovery supports may last far longer than the counseling relationships that are the core of addiction treatment. They also are far more likely to be delivered in the person’s natural environment and, nested within the person’s social network, often involve a larger cluster of family and community relationships.

In addition to the limitations noted above in current treatment approaches, the following premises underlie the provision of recovery support services:

Acute care models of addiction treatment are inadequate for people with high problem severity and complexity, as is evident in the low engagement rates, high attrition rates, low aftercare participation, and high readmission rates described above.

Persons with high personal vulnerability (family history, low age of onset of use, history of trauma) and problem severity and complexity (comorbidity), and with low recovery capital, may not fare well in the short-term but can achieve recovery when provided sustained recovery supports (White, Boyle, & Loveland, 2002; White et al., 2003).

Many people benefit from a personal “guide” who facilitates disengagement from the culture of addiction and offers a bridge to a culture of recovery (White, 1996); it can be extremely difficult to have to construct and cross this bridge on one’s own.

People who have overcome adversity can develop special sensitivities and skills in helping others experiencing the same adversity; this represents a “wounded healer” tradition that has deep historical roots in religious and moral reformation movements and is the foundation of modern mutual aid movements. In addition to the benefits of the person being healed, the healer himself or herself derives significant therapeutic benefit from the process of assisting others, known as the “helper therapy principle” (Reissman, 1965, 1990; also the recovery slogan: “To get it, you have to give it away”).

The treatment and recovery communities have become disconnected over the previous decades, and it would be in everyone’s best interest for the two communities to be linked back together. Recovery support services may be an especially effective way to accomplish this (Else, 1999; White, 2000a), moving the focus and locus of treatment from the institution to the person’s natural environment (White, 2002) and facilitating a shift from toxic drug dependence to “prodependence on peers” (Nealon-Woods, Ferrari, & Jason, 1995).

Recovery support services may be offered within several different models. They may be delivered within a clinical model (which views the recovery support provider as a kind of “treatment aide”) or within a community development model (which views the support provider as an organizer and catalyst for community recovery resource development). They also may be delivered within an acute care model of treatment (crisis intervention, clinical stabilization, and recovery initiation) or within a model of recovery management. Recovery management, like disease management, emphasizes a more sustained continuum of prerecovery, recovery initiation, and recovery maintenance supports. Recovery management models also are distinguished by sustained recovery monitoring (including recovery checkups), stage-appropriate recovery education, active linkage to indigenous communities of recovery, and early reintervention (Dennis, Scott, & Funk, 2003; White et al., 2002, 2003). Finally, recovery support services may be provided by paid or volunteer staff and may be delivered within existing treatment agencies, by local community providers (church, school, labor union), or by a grassroots and peer-run recovery advocacy or recovery support organization.

Given that there are multiple pathways to and styles of long-term recovery (White, 1996; White & Kurtz, 2005), it is incumbent upon the recovery support provider to

recognize the legitimacy of these multiple pathways, become conversant with the language and rituals reflected within these pathways, and develop relationships with the myriad groups representing these pathways;

work to expand the variety of recovery support structures within the communities he or she serves;

recognize that recovery can be sudden or incremental, that it can be initiated with or without professional intervention and with or without peer intervention, and that, regardless of how it was initiated, it may be sustained with and without such assistance as well;

understand that there are predictable stages in the long-term process of addiction recovery, but that these may not be linear or sequential in nature;

appreciate that services and supports that are crucial in one stage may be unhelpful or even harmful at another stage of recovery, and that service and support needs must be continually reassessed via sustained dialogue with the person in recovery;

acknowledge that he or she is not a sponsor, therapist, nurse, doctor, priest, reverend, rabbi, imam, and so on (at least not in his or her role as a recovery support provider);

be able to move flexibly, based on assessed need, between the roles of role model/mentor, resource broker, motivator/cheerleader, ally/confidant, truth teller, problem solver, and advocate and community organizer (White, 2006b).

Regarding the provision of recovery support services, we anticipate that their diversity, roles, and penetration rates will only continue to increase in the foreseeable future. This growth will require and facilitate changes in existing systems of care, expanding from their current focus on crisis intervention, active treatment, and recovery initiation to include outreach/engagement and pretreatment recovery support services, in-treatment recovery support services (to enhance engagement and reduce attrition), and posttreatment monitoring and stage-appropriate support services. As a result, there will be an increasing emphasis on the transfer of learning and skill acquisition from the current institutional-based approach to anchoring recovery within the person’s natural environment in the community. There is a danger, of course, that recovery support services may evolve as a separate system, disconnected from the national network of addiction treatment programs. The recent advances in this area are coming out of a new generation of grassroots recovery advocacy and support organizations who perceive many treatment programs as more concerned about their own institutional interests than the long-term recovery outcomes of those they serve (White, 2006a). This undercurrent of disenchantment and hostility (i.e., Holiday’s “damn fool” reference) and its sources will need to be openly confronted and resolved if the goal of a system of integrated clinical care and recovery support services is to be achieved. Lacking such resolution, the proliferation of recovery supports and their alienation from mainstream treatment could further fragment a system that is already difficult to navigate. The following principles are suggested as a foundation for integration.

Recovery support services and professionally directed addiction treatment services are complimentary rather than competitive and may be most effective when linked.

Recovery support specialists and treatment specialists must recognize, respect, and value the respective contributions each can make to the recovery process.

Recovery support specialists and treatment specialists must accurately represent and practice within the boundaries of their education, training, and experience. This principle must be based on mutual respect and the recognition that some services are best provided by traditionally trained professionals whereas others are best provided by peers and others with relevant life experiences and training. The expectation of respect for boundaries of competence applies to both roles.

A FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING RECOVERY SUPPORT SERVICES

In light of the discussion above, we would hypothesize that recovery support services, were they effective, would generate positive outcomes at the individual, program, and system level. At the system level, hypothesized outcomes would include (1) an increase the number of people entering addiction treatment (especially among those with high problem severity and/or comorbid conditions), (2) a decrease in the number of people “lost” from waiting lists to enter treatment, and (3) a diversion of individuals with lower problem severity and higher recovery capital away from intensive and costly services into natural recovery support systems in the community, leading to (4) a more equitable distribution of limited resources across a range of levels of care and varieties of support (consistent with the principle that there are multiple pathways to recovery).

At the program level, hypothesized outcomes would include (1) enhanced treatment retention and completion; (2) increased posttreatment abstinence outcomes; (3) a greater delay in the time period between discharge and first use following treatment (enhancing development of recovery capital); (4) decreases in the number, intensity, and duration of relapse episodes following treatment and a decrease in treatment readmission rates; and (5) a decrease in the time between relapse and reinitiation of treatment and recovery support services (preserving recovery capital and minimizing personal and social injury); resulting in (6) readmissions to less intensive, less costly levels and types of care.

At the level of the individual, hypothesized outcomes would include (1) enhanced recovery capital (e.g., employment, school enrollment, financial resources, stable housing, healthy family and extended family involvement, sobriety-based hobbies, life meaning and purpose, etc.), (2) decreases in the number and duration of episodes of care required to initiate recovery, (3) reduced attrition in first year affiliation rates with AA and other sobriety-based support groups, (4) an increase in self-reported satisfaction with care, (5) fewer and less frequent relapses, and (6) higher rates of sustained recovery.

EMPIRICAL SUPPORT FOR RECOVERY SUPPORT SERVICES

Prior to the introduction of the phrase recovery support services, there was a small but growing literature suggesting the effectiveness of various of these services, particularly those that were peer facilitated (Durlak, 1979; Hattie, Sharpley, & Rogers, 1984; Reissman, 1990) and particularly within the arena of addiction recovery (Blum & Roman, 1985; Connet, 1980; Galanter, Castaneda, & Salamon, 1987). The most widely researched of these, of course, has been 12-Step, mutual support groups, such as AA. Notable variations in research methods and outcomes confound definitive assessment of the effectiveness of 12-Step approaches compared to other interventions, but systematic reviews indicate that they are generally associated with improved substance use outcomes (Bogenschutz, Geppert, & George, 2006; Ferri, Amato, & Davoli, 2007). There is some support, such as results from Project Match (Barbor & Del Boca, 2002) that 12-Step participation assists with continued abstinence over time (Humphreys et al., 2004; Weisner, Delucchi, Matzger, & Schmidt, 2003). Participation in Double Trouble in Recovery, a 12-Step-based approach designed specifically for adults with co-occurring disorders, also has been associated with reduced substance abuse and psychiatric symptoms and higher medication adherence and sense of well-being in comparison to traditional 12-Step programs (Laudet, Magura, Vogel, & Knight, 2000; Magura, Laudet, Mahmood, Rosenblum, & Knight, 2002; Magura et al., 2003). Finally, in a randomized study with adults with co-occurring disorders, those who worked with a peer counselor and received case management experienced fewer crisis events, hospitalizations, and episodes of substance use compared to those with case management alone (Klein, Cnaan, & Whitecraft, 1998).

Studies also consistently reveal that providing a greater number of collateral services (e.g., medical, psychiatric, family, employment services) as part of substance use treatment is associated with better substance use outcomes and better social adjustment (McLellan et al., 1994). Directly providing supplemental medical, psychiatric, and social services or linking clients to such resources via assertive case management can increase outcomes across multiple domains, by as much as 25% to 40% (McLellan et al., 1998). Utilization of such services are dramatically increased when provided onsite at addiction treatment facilities compared to referral to other programs (Berkman & Wechsberg, 2007), but onsite delivery of these services is currently the exception rather than the rule (D’Aunno, 2006).

One recovery support service that is being increasingly investigated outside of addiction treatment programs is supported housing. Despite the belief of some providers and policy makers that treatment and abstinence need to occur before independent residence, longitudinal studies show that adults can be stably housed without increased drug use for up to 5 years by receiving “housing first”: a model in which people who are homeless or unstably housed are placed in supported housing prior to, and as a foundation for, agreeing to accept treatment for their addiction (Padgett, Gulcur, & Tsemberis, 2006; Lipton, Seigel, Hannigan, Samuels, & Baker, 2000; Mares, Kasprow, & Rosenheck, 2004; Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004). In fact, compared to veterans who received short-term case management alone, those who received housing subsidies and case management had significantly fewer days of alcohol and drug use and periods of intoxication (Cheng, Lin, Kasprow, & Rosenheck, 2007).

Other recovery support services that have been shown to increase engagement and retention in addiction treatment and improve outcomes include transportation and child care. For example, results from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) showed that offering transportation to individuals significantly improved treatment access and retention in outpatient methadone and drug abuse treatment (Friedmann, D’Aunno, Jin, & Alexander, 2000; Friedmann, Lemon, & Stein, 2001). Furthermore, Marsh et al. (2004) found that an enhanced treatment program that included outreach, transportation, and child care was associated with increased service engagement and reduced drug use in substance-abusing mothers.

In addition to these controlled trials, research and practice developed in Connecticut in collaboration with the state’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) over the past decade has contributed to our understanding of the role of recovery support services in engaging persons with addictions into treatment. Starting in the early 1990s and continuing up to the present, these efforts have included program development and evaluation in the areas of (1) outreach and engagement to homeless persons with addictions (with and without co-occurring mental illnesses), (2) peer-based outreach and engagement to persons with co-occurring disorders, (3) peer-and group-based interventions geared toward community integration for persons with co-occurring disorders, and (4) recovery support services for persons with addictions accessing ATR vouchers.

Outreach and Engagement to Persons with Addictions

The principles of assertive outreach to persons who are homeless include (1) “starting where they are” both physically in terms of their life on the streets and in emergency shelters, and existentially in terms of what they see as their wants and needs (Cohen & Marcus, 1992; Lamb, Bachrach, Goldfinger, & Kass, 1992); (2) respecting their survival strengths (Chafetz, 1992); (3) building trust by engaging with them as persons first not as patients (Brickner, 1992; Susser, Goldfinger, & White, 1990); (4) providing a range of services—housing, help with entitlements and obtaining work, social needs, and others—to them in addition to treatment (Cohen & Marcos, 1992); and(5) following the dual principle of making to these persons only the promises that you can keep and keeping the promises that you do make (Rowe, 1999).

In terms of its status as a recovery support service, the outreach and engagement approach is particularly strong in the areas of connecting the person to financial, material, and instrumental resources; referral to and help in gaining access to housing and housing supports; and encouragement for developing as sense of self-efficacy based on personal strengths and choices. Outreach and engagement has proven to be an effective method of making contact with and engaging people who are homeless and mentally ill or who have co-occurring disorders into treatment and case management (Lam & Rosenheck, 1999), and it is associated with improved client outcomes in several domains (Rosenheck, 2000). Until a few years ago, however, little research had been conducted on the use of assertive outreach for persons who primary have addictions.

In 2000, DMHAS began to fund outreach services that target persons with addictions as well as those with co-occurring disorders. This initiative was inspired in part by the success of recent innovations in substance abuse treatment such as the “motivational enhancement” or “motivational engage ment” approach. This approach recognizes that persons with addictions often are ambivalent about treatment and need to be persuaded to change their behavior through an incremental, graduated process that includes the phases of precontemplation, contemplation, determination, action, and maintenance (Miller & Rollnick, 1991; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). The motivational engagement approach shares an immediate kinship with the phases of brief but repeated contact, trust building, acceptance of treatment, and ongoing clinical stability that have been shown to be effective in outreach and engagement services.

A first study of this expansion of outreach and engagement services to persons with addictions included analysis of the characteristics of, and engagement process for, 20 consecutive individuals with addictions whom outreach workers contacted. For each individual, we reviewed both service needs that these persons or outreach workers identified, and what, if any, services they actually received from the homeless outreach team. Preliminary findings, compared to the team’s traditional target group of persons with mental illness or co-occurring disorders, were that (1) persons with primary addictions had more significant work histories, along with higher previous social standing and social networks, than persons with psychiatric disorders;(2) it appeared that, in addition to the instrumental advantages of work and social histories, persons with addictions lacked a deeply ingrained sense of “otherness” that marked many persons with serious mental illness. The former, that is, could see themselves as whole persons who had an addictions problem, whereas the latter, paraphrasing Goffman’s (1963) formulation of stigma, were more likely to see themselves as having tainted identities in their own eyes and in the eyes of others, posing an additional disadvantage in their efforts to reintegrate into mainstream society; and (3) the treatment trajectory for persons with addictions appeared to be quite different from that of persons with mental illness: drug detoxification and treatment beds facilitated continuity in the case management relationship; however, these services often had waiting lists or insurance requirements that rendered them unavailable or less available than needed, whereas mental health care was generally available and could be initiated for clients more quickly than addiction services (Rowe, Frey, Fisk, & Davidson, 2002).

Peer-Based Outreach and Engagement to Persons with Co-occurring Disorders

Early on in the provision of outreach services to persons with co-occurring disorders, we hypothesized—based on our limited experience with staff who disclosed their personal experience with mental illness and/or addiction and our knowledge of a few studies on the use of peer staff in mental health services (e.g., Davidson et al., 1999; Davidson, Weingarten, Steiner, Stayner, & Hoge, 1997)—that peers could make a unique contribution to engaging and building relationships with clients. We began to integrate peers as staff into an outreach and engagement team and, using qualitative research methods, gained confidence that peers had a unique role to play in the engagement process (Fisk & Frey, 2002; Fisk, Rowe, Brooks, & Gildersleeve, 2000). Operating on a strengths-based model, the peer outreach approach offered, among other recovery support domains, positive recovery role models and mentoring and encouragement in developing a sense of self-efficacy and the motivation to engage and maintain oneself in the work of recovery.

Then, in 2000, DMHAS initiated a statewide Peer Engagement Specialist project involving the deployment of peer staff on community-based outreach teams. We conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing peer engagement services to regular case management for clients who were rated as unengaged in treatment. Nearly three fourths of the clients enrolled in this study had co-occurring addictions. Study results showed that clients perceived higher positive regard, understanding, and acceptance from providers in the peer as compared to the regular case management condition at 6 months following enrollment into the study, with initially unengaged clients showing increasing contacts with case managers in the peer condition, and decreasing contacts in the regular condition. We concluded that early in treatment, peer providers may possess distinctive skills in communicating positive regard, understanding, and acceptance to clients, and a facility for increasing treatment participation among the most disengaged clients, with positive treatment relationship elements leading to greater motivation for addiction and mental health treatment. These findings suggest that peer providers can serve a valued role in quickly forging therapeutic connections with persons, particularly those with dual disorders, who are typically considered to be among the most alienated from behavioral health care (Sells, Davidson, Jewell, Falzer, & Rowe, 2006).

Peer- and Group-Based Interventions Geared Toward Community Integration for Persons with Co-occurring Disorders

Although we were encouraged with our findings of peer-on-peer outreach and engagement services integrated into outreach teams, we wanted to explore the potential of providing peer-based services that (1) operated independently of or in a complementary fashion to clinical care and (2) drew on small group community building and support strategies to encourage recovery and community engagement. As recovery support services, the approach we took with two separate interventions—the Citizens Project and the Engage Study—involved the use of paid peer staff with stipends for participants in interventions that combined elements of strengths-based community development and mutual support recovery models and emphasized community activities and building community connections, positive role models and mentoring, development of internal resources of confidence and self-efficacy, and identification of interests, assets, and goals.

The Citizens Project was built on a theoretical framework of “citizenship,” which we defined as a measure of the strength of people’s connections to the rights, responsibilities, roles, and resources available to them through public and social institutions, and through the informal, “associational” life of neighborhoods and local communities (Rowe, 1999; Rowe et al., 2001). Using random assignment, we compared a citizenship intervention, involving nontraditional classes and valued role projects with wraparound peer support, along with standard clinical care including jail diversion services, to standard clinical care with jail diversion services alone, in reducing alcohol use, drug use, and criminal justice charges among a study group of 114 persons with severe mental illnesses. Approximately three fourths of participants had co-occurring addictions. The intervention group showed significantly reduced alcohol use compared to the control group. In addition, results showed a significant group by time interaction, where alcohol use decreased over time in the experimental (peer services) group and increased in the control (case management) group. Drug use and criminal justice charges decreased significantly across assessment periods in both groups (Rowe et al., 2007).

A second study, funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse, examined the effectiveness of an integrative group model that blended clinical, rehabilitation, mutual support, and intensive case management components. This group model called Engage targeted social isolation, demoralization, and disconnection from mental health and substance abuse services and abstinence-based self-help groups as factors that, we hypothesized, would mediate medication and outpatient treatment adherence and cycles of rehospitalization among adults with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. One-hundred-and-seventeen participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: standard care (n = 40), skills training (n = 42), or engage (n = 35). This study found that at a 9-month follow-up period, in comparison to standard care, participants in the community-based peer engagement condition experienced a greater reduction in alcohol problems, a greater increase in social functioning and beliefs in the importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems, and a significantly greater increase in use of professionally based services. As a result, individuals in the peer-based intervention also experienced a greater decrease in hospitalizations over time than participants receiving standard care alone.

Recovery Support Services for Persons with Addictions Accessing ATR Vouchers

A final indication of the potential effectiveness of recovery support services comes from a preliminary analysis of the outcomes generated by Connecti cut’s experience with the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) Access to Recovery (ATR) initiative. To date, approximately 84% of the ATR dollars received by Connecticut have been spent (via client-held vouchers) on recovery support services, with the remaining 16% spent on clinical services. Although during the period prior to ATR the rate of self-reported abstinence from alcohol in the previous month among service recipients was 72.6%, this rate increased to 89.2% following the introduction of ATR. Similarly, the rate of binge drinking (i.e., five or more drinks in one sitting) decreased by 62.5% (from 14.7% to 5.5%) and the rate of illegal drug use decreased by 57.5% (from 34.8% to 20.0%). Furthermore, the receipt of a number of recovery support services, such as housing and vocational services, significantly predicted reductions in alcohol and illicit drug use. Compared to adults who received either only clinical services (e.g., intensive outpatient services) or only recovery support services, those who received both types of services had significantly greater reductions in past month alcohol use (p = .036) and illegal drug use (p = .002).

DISCUSSION

The empirical evidence reviewed above suggests that recovery support services can play a variety of important roles in engaging people into care, supporting them while they are in care, and helping them to achieve better outcomes from care. Given that so many of these studies either targeted or included large numbers of individuals with co-occurring psychiatric disorders and addictions, one might reasonably argue that the need for, and effectiveness of, recovery support services might be due solely to the presence of serious mental illnesses in these study populations. After all, recovery support services have a long and well-documented history of effective use among adults with serious mental illnesses, and it therefore would make sense that adults who had serious mental illnesses in addition to addictions might similarly need and benefit from such services. To this interpretation of our findings, we suggest the following two responses.

First, the epidemiologic and service use data we reported above suggested that roughly one half of all adults with addictions have a co-occurring psychiatric illness. Were the utility of recovery support services limited to those individuals with co-occurring mental illnesses, then these services would still remain relevant and useful for approximately one half of the population of people with addictions. Among these individuals, only between 4% and 20% currently receive treatments for both disorders, and between 29% and 71% currently receive no treatment at all (Friedmann et al., 2004; Marsh et al., 2004; Smith & Marsh, 2002; Watkins et al., 2001). Clearly there is much room for improvement in meeting the needs of this population, and recovery support services would seem to offer one significant step forward in doing so.

Second, however, the more recent Access to Recovery initiative offers an exception to this rule and raises the question of the need and utility of recovery support services for the broader population of individuals with addictions. Given that ATR resources can only be used as a last resort—meaning that all other existing and available resources would have to have been exhausted first—people with serious mental illnesses are unlikely to make up a significant proportion of the population of people receiving ATR-funded care. Such individuals would likely be screened for and referred to other services within the system that are supported by Medicaid, federal, or other public funds. The initial ATR evaluation thus begins to provide some data to indicate the importance of recovery support services even for individuals who may not suffer from a co-occurring mental illness. Future research is needed to confirm and expand upon these initial findings.

In the interim, many issues remain unresolved in relation to this relatively new form of care. Questions revolve around issues of credentialing and reimbursement (e.g., who can provide recovery support services, what kind of training is required, who will pay for these services?), the relationship between recovery support services and more conventional clinical care (e.g., should recovery support services remain peripheral to the formal network of addiction treatment or be brought into and integrated with formal treatment, at what cost, and with what expected benefits?), the professional role and career trajectory of recovery support providers (e.g., do people have to be in recovery themselves to provide these services, are these dead-end jobs or is there career mobility, how is supervision provided and by whom?), and the ethical quandaries that arise in relation to boundary maintenance, dual roles, and others (e.g., when is taking someone out for coffee a reimbursable service and when it is reflective of a friendship, when and for whom is disclosure to be used, about what, and for what purposes, can someone work in an agency where they previously received, or currently receive, services?). Rather than waiting for all of these issues to be resolved, the field appears to be moving ahead in embracing this alternative form of service delivery within the addictions arena. Our hope is that research and evaluation will keep pace with these developments, so that the nature, role, and benefits of these services can be made clear to providers and people in recovery alike.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by Grant #DA13856 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

See special issue of Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment Volume 15, Number 1, 1998.

Contributor Information

LARRY DAVIDSON, Program for Recovery and Community Health, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut USA.

WILLIAM WHITE, Chestnut Health Systems, Port Charles, Florida USA.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD, Hser Y, & Grella CE (1997). Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcomes Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11, 308–323. [Google Scholar]

- Barbor TF, & Del Boca FK (2002). Treatment matching in alcoholism. NewYork: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, & Wechsberg WM (2007). Access to treatment-related and support services in methadone treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum T, & Roman P (1985). The social transformation of alcoholism intervention: Comparison of job attitudes and performance of recovered alcoholics and non-alcoholic alcoholism counselors: A survey. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26(4), 365–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Geppert CM, & George J (2006). The role of twelve-step approaches in dual diagnosis treatment and recovery. American Journal on Addictions, 15(1), 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer P (1978). Urban masses and moral order in America, 1820–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer DD, Catalano RF, Haggerty K, Gainey RR, & Fleming CB (1998). A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction, 93, 73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner PW (1992). Medical concerns of homeless persons In Lamb RH, Bachrach LL, & Kass FI, (Eds.), Treating the homeless mentally ill: A report of the Task Force on the Homeless Mentally Ill (pp. 249–261). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Chafetz L (1992). Why clinicians distance themselves from the homeless mentallyill In Lamb RH, Bachrach LL, & Kass FI (Eds.), Treating the homeless mentally ill: A report of the Task Force on the Homeless Mentally Ill (pp. 95–107). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Lin H, Kasprow W, & Rosenheck RA (2007). Impact of supported housing on clinical outcomes: Analysis of a randomized trial using multiple imputation technique. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NL, & Marcos LR (1992). Outreach intervention models for the homeless mentally ill In Lamb RH, Bachrach LL, & Kass FI (Eds.), Treating the homeless mentally ill: A report of the Task Force on the Homeless Mentally Ill (pp. 141–157). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Connet GE (1980). Comparison of progress of patients with professional and para-professional counselors in a methadone maintenance program. International Journal of the Addictions, 15, 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyhis D, & White W (2006). Alcohol problems in Native America: The untold story of resistance and recovery. Colorado Springs, CO: White Bison, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aunno T (2006). The role of organization and management in substance abuse treatment: Review and roadmap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31, 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, Weingarten R, Stayner D, & Tebes JK (1999). Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, & Strauss JS (1992). Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65, 131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Weingarten R, Steiner J, Stayner D, & Hoge M (1997). Integrating prosumers into clinical settings In Mowbray CT, Moxley DP, Jasper CA, & Howell LL (Eds.), Consumers as providers in psychiatric rehabilitation (pp. 437–455). Columbia, MD: International Association for Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA (1996). Correlates of past-year status among treated and untreated persons with former alcohol dependence: United States, 1992. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 20, 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, & Ruan WJ (2005). Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction, 100(3), 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, & Funk R (2003). An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26, 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J (1979). Comparative effectiveness of professional and paraprofessional helpers. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 80–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else JD (1999). Recovering recovery. Journal of Ministry in Addiction & Recovery,6(2), 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri M, Amato L, & Davoli M (2007). Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programmes for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3:CD005032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk D, & Frey J (2002). Employing people with psychiatric disabilities to engage homeless individuals through supported socialization: The Buddies Project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 26(2), 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk D, Rowe M, Brooks R, & Gildersleeve D (2000). Integrating consumer staff members into a homeless outreach project: Critical issues and strategies. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 23(3), 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, D’Aunno TA, Jin L, & Alexander JA (2000). Medical and psychosocial services in drug abuse treatment: Do stronger linkages promote client utilization? Health Services Research, 35(2), 443–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Hendrickson JC, Gerstein DR, Dean R, & Zhang Z (2004). The effect of matching comprehensive services to patients’ needs on drug use improvement in addiction treatment. Addiction, 99, 962–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidmann PD, Lemon S, & Stein MD (2001). Transportation and retention in outpatient drug abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 21, 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Castaneda R, & Salamon I (1987). Institutional self-help therapy for alcoholism: Clinical outcome. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 11(5), 424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York:Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, & Cloud W (1999). Coming clean: Overcoming addiction without treatment. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, & Simpson DD (2000). Contingency management in outpatient treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattie JA, Sharpley CF, & Rogers HJ (1984). Comparative effectiveness of professional and paraprofessional helpers. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 534–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, & Anderson J (2003). Overview of 5-year follow-up outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome studies (DATOS). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Flynn PM, Craddock G, & Fletcher B (2001). Relapse after drug abuse treatment In Tims F, Leukfield C, & Platt J (Eds.), Relapse and recovery in addictions (pp. 109–121). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K Wing S, McCarty D, Chappel J, Gallant L, Haberle B, Horvath AI, Kashutas LA, Kirk T, Kivlahan D, Laudet A, McCrady BS, McLellan AT, Morgenstern J, Towsend M, & Weiss R (2004). Self-help organizations for alcohol and drug problems: Toward evidence-based practice and policy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1998). Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR, & Bishop PD (2006). Oxford House: A review of research and implications for substance abuse recovery and community research. Journal of Drug Education, 31(1), 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC (1997). The lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, & Leaf PJ (1996). The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AR, Cnaan RA, & Whitecraft J (1998). Significance of peer social support with dually diagnosed clients: Findings from a pilot study. Research on Social Work, 8, 529–551. [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann HKH, & Sobbell LC (2001). Introduction: Natural recovery research across substance use. Substance Use and Misuse, 36(11), 1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J, & Rosenheck RA (1999). Street outreach for homeless persons with mental illness: Is it effective? Medical Care, 37, 894–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RH, Bachrach LL, Goldfinger SM, & Kass FI (1992). Summary and recommendations In Lamb RH, Bachrach LL, & Kass FI (Eds.), Treating the homeless mentally ill: A report of the Task Force on the Homeless Mentally Ill (pp. 1–10). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Magura S, Vogel HS, & Knight E (2000). Addiction services: Support, mutual aid, and recovery from dual diagnosis. Community Mental Health Journal, 36, 457–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton FR, Siegel C, Hannigan A, Samuels J, & Baker S (2000). Tenure in supportive housing from homeless persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 51, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, & Higgins ST (2006). A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Laudet AB, Mahmood D, Rosenblum A, & Knight E (2002). Adherence to medication regimens and participation in dual-focus self-help groups. Psychiatric Services, 53, 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Laudet AB, Mahmood D, Rosenblum A, Vogel HS, Knight EL (2003). Role of self-help processes in achieving abstinence among dually diagnosed persons. Addictive Behaviors, 28, 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares AL, Kasprow WJ, & Rosenheck RA (2004). Outcomes of supported housing for homeless veterans with psychiatric and substance abuse problems. Mental Health Services, 6, 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D, & D’Aunno T (2004). Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27, 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, D’Aunno TA, & Smith BD (2000). Increasing access and providing social services to improve drug abuse treatment for women with children. Addiction, 95, 1237–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul ME, Svikis DS, & Moore RD (2001). Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: Patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 62(1), 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MR, O’Brien CP, Koppenhaver JM, & Shepard DS (1999). Continuing care for cocaine dependence: Comprehensive 2-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, Koppenhaver JM, & Pettinati HM (2004). The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12 month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Metzger DS, Grisson GR, Woody GE, Luborsky L, et al. (1994). Similarity of outcome predictors across opiate, cocaine, and alcohol treatments: Role of treatment services. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 62(6), 1141–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, & Kleber HD (2003). Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, Gould F, Meyers K, Bencivengo M, et al. (1998). Supplemental social services improve outcomes in public addiction treatment. Addiction, 93(10), 1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan CO, Nich N, & Carroll KM (2004). Ethnic differences in substance abuse treatment retention, compliance, and outcome from two clinical trials. Psychiatric Services, 55, 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R (2004). Which substance abuse treatment facilities offer dual diagnosis programs? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30, 525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealon-Woods M, Ferrari J, & Jason L (1995). Twelve-Step program use among Oxford House residents: Spirituality or social support for sobriety? Journal of Substance Abuse, 7, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Gulcur L, & Tsemberis S (2006). Housing first services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Research on Social Work Practice, 16, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML, Podus D, & Chang E (2000). Program factors and treatment outcomes in drug dependence treatment: An examination using meta-analysis. Substance Use and Misuse, 35, 1931–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML, Podus D, Chang E, & Urada D (2002). The effectiveness of drug abuse treatment: A meta analysis of comparison group studies. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 67, 53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, & Roll J (2006). Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 101(11), 1546–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, & Norcross JC (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp CA (1998). The strengths model: Case management with people suffering from severe and persistent mental illness. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ray GT, Weisner CM, & Mertens JR (2005). Relationship between use of psychiatric services and five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 56, 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, & Godwin FK (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association, 264, 2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissman F (1965). The “helper-therapy” principle. Social Work, 10, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Reissman F (1990). Restructuring help: A human services paradigm for the 1990s.American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, McKellar JD, Finney JW, Otilingam PG, & Moos RH (2002). Psychiatric comorbidity, continuing care and mutual help as predictors of five-year remission from substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R (2000). Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: The application of research to policy and practice. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M (1999). Crossing the border: Encounters between homeless people and outreach workers. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Bellamy C, Baranoski M, Wieland M, O’Connell M, Benedict P, et al. (2007). A peer-support, group intervention to reduce substance use and criminality among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58, 955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Frey J, Fisk D, & Davidson L (2002). Engaging persons with substance use disorders: Applying lessons from mental health outreach to homeless persons. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 29(3), 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Kloos B, Chinman M, Davidson L, & Cross A (2001). Homelessness, mental illness, and citizenship. Social Policy and Administration, 35, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M (2002). The response of African American communities to addiction: An opportunity for treatment providers. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 20(3/4), 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sells D, Davidson L, Jewell C, Falzer P, & Rowe M (2006). The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, & Brown BS (1997). Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 11, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, & Rowan-Szal GA (1997). Drug abuse treatment retention and process effects on follow-up outcomes. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 47(3), 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueland L Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Barber JP, Griffien ML, Thase ME, Daley D, Frank A, Gastfriend DR, Blaine J, Connolly MB, & Gladis M (2002). Retention in psychosocial treatment of cocaine dependence: Predictors and impact on outcome. American Journal of Addictions, 11, 24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueland L, Crits-Christoph P, Gallop B, Gastfriend D, Lis J, Frank A, Griffin M, Blaine J, & Luborsky L (2002). Who starts treatment: Engagement in the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. American Journal of Addictions, 11, 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, & Marsh JC (2002). Client-service matching in substance abuse treatment for women with children. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 22, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, & Sobell MB (1996). Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: Prevalence in two population surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 966–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, & Shadish WR (1997). Outcome, attrition, and family couples’ treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 170–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark M (1992). Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: A clinically oriented review. Clinical Psychology Review, 12(1), 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2002a). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2000 data on substance abuse treatment facilities (DHHS publ. no. SMA 02–3668). Rockville, MD: Author, Office of Applied Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2002b). Report to Congress on the prevention and treatment of co-occurring substance abuse disorders and mental disorders. Rockville, MD: Author, Office of Applied Studies; Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/reports/congress2002/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2003). Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS publ. no. SMA 03–3836). Rockville, MD: Author, Office of Applied Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Goldfinger SM, & White A (1990). Some clinical approaches to the homeless mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 25(5), 463–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AS, Blankenship KM, Selwyn PA, Khoshnood K, Lopez M, Balacos K, et al. (1998). Evaluation of an innovative program to address the health and social service needs of drug-using women with or at risk for HIV infection. Journal of Community Health, 23(6), 419–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, & Rubel E (1999). Natural recovery from cocaine dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13(4), 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, Glucur L, & Nakae M (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldorf D, Reinarman C, & Murphy S (1991). Cocaine changes: The experience of using and quitting. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Burnam A, Kung F, & Paddock S (2001). A national survey of care for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1062–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Delucchi K, Matzger H, & Schmidt L (2003). The role of community services and informal support on five-year drinking trajectories of alcohol dependent and problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 862–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, & Sherbourne C (2001). Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 2027–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W (1996). Pathways from the culture of addiction to the culture of recovery.Center City, MN: Hazelden. [Google Scholar]

- White W (1998) Slaying the dragon: The history of addiction treatment and recovery in America. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- White W (2000a). The history of recovered people as wounded healers: II. The era of professionalization and specialization. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 18(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- White W (2000b). The role of recovering physicians in 19th century addiction medicine: An organizational case study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 19(2), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W (2001). Pre-AA alcoholic mutual aid societies. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 19(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- White W (2002). An addiction recovery glossary: The languages of American communities of recovery. Available at www.bhrm.org and www.efavor.org.

- White W (2006a). Let’s go make some history: Chronicles of the new addiction recovery advocacy movement. Washington, DC: Johnson Institute and Faces and Voices of Recovery. [Google Scholar]

- White W (2006b). Sponsor, recovery coach, addiction counselor: The importance of role clarity and role integrity. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health. [Google Scholar]

- White W, Boyle M, & Loveland D (2002). Alcoholism/addiction as a chronic disease: From rhetoric to clinical reality. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 20(3/4), 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- White W, Boyle M, & Loveland D (2003). Recovery management: Transcending the limitations of addiction treatment. Behavioral Health Management 23(3), 38–44. Available at http://www.behavioral.net/2003_05-06/featurearticle.ht. [Google Scholar]

- White W, Boyle M, & Loveland D (2004). Recovery from addiction and recovery from mental illness: Shared and contrasting lessons In Ralph R & Corrigan P (Eds.), Recovery and mental illness: Consumer visions and research paradigms (pp. 233–258). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- White WL, & Godley MD (2003). The history and future of “aftercare.” CounselorMagazine, 4(1), 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- White W, & Kurtz E (2005). The varieties of recovery experience. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care, 3(1/2), 21–61. [Google Scholar]

- White W, & Kurtz E (2006). Linking addiction treatment and communities of recovery: A primer for addiction counselors and recovery coaches. Pittsburgh, PA: IRETA/NeATTC; (Institute for Research, Education, and Training in Addictions of the Northeast Addiction Technology Transfer Center.) [Google Scholar]