Abstract

Objectives:

In women receiving sterilization, the removal of the entire fallopian tube, a procedure referred to as a risk-reducing salpingectomy (RRS), reduces subsequent ovarian cancer risk compared with standard tubal sterilization procedures. There are limited data on which surgical procedure women will choose when educated about the benefits of an RRS. Our objective was to study the proportion of women desiring sterilization that would choose an RRS.

Methods:

This cohort study included women 30 years of age and older with a living biological child who requested laparoscopic sterilization at a tertiary academic hospital. Participants were given a decision aid and offered an RRS or a standard tubal sterilization procedure with titanium clips. The primary outcome was to determine the proportion of women who would choose an RRS. Other outcomes included estimated blood loss and operative time, which was compared between groups, along with complications.

Results:

Fourteen of the 18 (78%) women who participated in our study chose RRS. Estimated blood loss and operating time were similar among women who underwent RRS and standard tubal sterilizations. There were no significant complications in either group. The study was ended early based on emerging data and a change in national practice patterns.

Conclusions:

Because of the elective nature of sterilization and the complexities of cancer risk reduction, a patient-centered approach is beneficial for sterilization counseling. Our results support offering RRS as an alternative to standard tubal sterilization.

Keywords: laparoscopic surgery, patient centered, risk reducing, salpingectomy, sterilization

Female sterilization is the most commonly used form of contraception worldwide.1 In the United States, 25.1% of reproductive-age women use sterilization as their method of contraception, with approximately 600,000 surgical sterilizations performed annually in the United States.2 Risk-reducing salpingectomy (RRS) is a relatively new surgical approach for women who desire female sterilization, a procedure that removes the entire fallopian tube and reduces the subsequent incidence of ovarian cancer.3 Patient-centered care for contraception requires that surgeons understand women’s preferences for sterilization, as well as the risks and benefits of the sterilization method used.4 There is strong although not conclusive evidence to support that women who have undergone RRS as compared with a tubal interruption procedure will have a lower likelihood of developing ovarian cancer later in life.5,6 In a Danish nationwide register-based, case-control study that evaluated all pelvic serous or borderline cancers during a 30-year period, Madsen et al5 found that receiving a bilateral salpingectomy decreased the odds of subsequent ovarian cancer by 42% (odds ratio [OR] 0.58, confidence interval [CI] 0.36–0.95), compared with a decreased odds of 13% (OR 0.87, CI 0.78–0.98) from traditional sterilization.5 In their nested case-control study using a US-based database, Lessard-Anderson and colleagues6 found a similar effect of performing RRS compared with traditional sterilization, with a decreased odds of 64% (OR 0.36, CI 0.12–1.02) for developing ovarian cancer after RRS compared with a 41% (OR 0.59, CI 0.29–1.17) reduction following traditional sterilization.6 Research suggests this is biologically plausible as the precursor lesion most commonly originates in the distal fallopian tubes.7 Women may choose an RRS when offered because ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecological cancer and the most common cause of gynecological cancer death in the United States, with an annual incidence of 21,000 cases and 14,000 deaths.7

The benefits of RRS compared with traditional sterilization include a potentially greater risk reduction in epithelial ovarian cancer,3,5,6 and a reduction in sterilization failure and resulting ectopic pregnancy, which occurs in 50% of sterilization failures.8 Sterilization failure resulting in pregnancy occurred in approximately 0.4% of standard tubal sterilization procedures.8 Risks of RRS may include premature ovarian failure.9 This can occur when small arterial blood vessels are ligated in the mesosalpinx, resulting in reduction in ovarian function.9–13 To date, there have been no high-quality, longitudinal studies evaluating the specific impact of bilateral salpingectomy on long-term ovarian function, but results from short-term studies and those extrapolated from infertility research have been largely reassuring.10,11,13 One study, however, demonstrated a significant increase in serum follicle-stimulating hormone and a significant decrease in antimullerian hormone in women who underwent salpingectomy compared with patients who did not undergo this procedure.12 Even if findings such as the one by Ye et al12 can be replicated, it is not clear whether those findings will translate into clincally signficant outcomes, such as earlier menopause for women who receive RRS compared with the traditional sterilization procedure.

An additional risk of RRS includes a decrease in options for women who experience poststerilization regret. Without any remaining tubal tissue, women who received an RRS must undergo in vitro fertilization if they desire subsequent pregnanices, which typically requires significantly more resources compared with other sterilization reversal procedures.14 Finally, RRS may be assosciated with greater operative risk. When RRS is performed postpartum or immediate postcesarean, the mesosalpinx is engorged and the risk of greater blood loss is feasible. When RRS is performed as an interval procedure (not assosciated with a delivery), many surgeons who currently perform sterilization through a single port would need additional ports, increasing the risk of injury.

Published data on women’s preferences of laparoscopic sterilization compared with RRS are sparse. We aimed to determine the proportion of women seeking sterilization who would choose an RRS when offered both sterilization options. We ended our study before achieving our recruitment goal because of a major publication supporting the safety of RRS15 and the publication of expert opinion advocating for RRS to be offered as a method of sterilization outside of a research context.4

Methods

This cohort study was undertaken at a tertiary academic hospital. Ethics approval was received from the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina. We screened all women who presented for interval surgical sterilization. Eligible participants included English- and Spanish-speaking women 30 years of age and older with a living biological child who desired surgical sterilization as an interval procedure. All of the potential participants were seen within the four clinics that offer sterilization at the Obstetrics and Gynecology (OBGYN) Department at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. A study investigator approached women at their preoperative appointment for their sterilization consultation and provided an informational brochure (see Supplemental Appendix, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A82). After a verbal explanation of the study, the investigator offered a choice between traditional tubal sterilization via titanium clip (the standard of care at this institution) and total bilateral RRS. All of the participants spoke with a physician study investigator before signing the study consent.

OBGYN trainees (residents or fellows) and attending physicians composed the surgical teams that completed all study sterilizations, as is the standard of care at this academic institution. The standard surgical approach for traditional sterilization procedures uses single-port laparoscopy in which tubal interruption is achieved by titanium clips occluding the fallopian tubes. Subjects who opted for RRS either underwent salpingectomy using a bipolar tissue-sealing system, or with other laparoscopic equipment, based on the preference of the attending surgeon. Following the sterilization, study staff abstracted information from the operative report, including procedure time, estimated blood loss (EBL), and any complications noted. Regarding EBL, when surgeons did not specify an exact amount (ie, “less than 10 mL”), the integer on the report was used (ie, 10). When EBL was reported as “minimal,” 5 mL was used. Surgical specimens were not sent to pathology unless requested by the attending physician. We called all of the women at 1 and 6 weeks postoperatively and asked about complications, including hospital readmission, infection, or other unscheduled clinic visit. At the 6-week postoperative telephone call, women were asked if they would recommend RRS to a friend who was considering sterilization.

Our sample size was one of convenience. We planned on 24 months of recruitment for a total of 50 subjects, which was a reasonable estimate given the volume of patients seeking sterilization. Although no formal power calculation was performed, we believed that including 50 participants would be adequate to assess the proportion of women who would choose RRS and assess the feasibility of completing the procedure for those who opted for RRS. At our hospital, approximately 36 interval sterilizations are performed each year in women 30 years old and older. We anticipated being able to recruit 75% of eligible women seeking sterilization, and expected half to choose RRS and half to choose traditional sterilization. We stopped recruitment after 11 months as a result of the publication of a large study that reported on the safety of RRS15 and a publication of expert opinion in support of routinely offering RRS outside of a research context.4

Our primary outcome was the proportion of participants who underwent RRS. Other outcomes included operative time, EBL, and complications. Because of the small number of participants who opted for the control procedure in the study, we analyzed data from historical controls who received standard sterilization in the previous year to the study and compared the historical controls with the RRS group. Data from 22 historical controls were abstracted, and information on age, parity, race, ethnicity, insurance status at the time of the procedure, body mass index, and operative information including surgical time and EBL from the operative report were collected. Demographic and outcome characteristics were compared with descriptive statistics. Median scores also were reported because the data were not normally distributed, and therefore, nonparametric tests were used for comparison. All of the statistical tests were performed using STATA 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

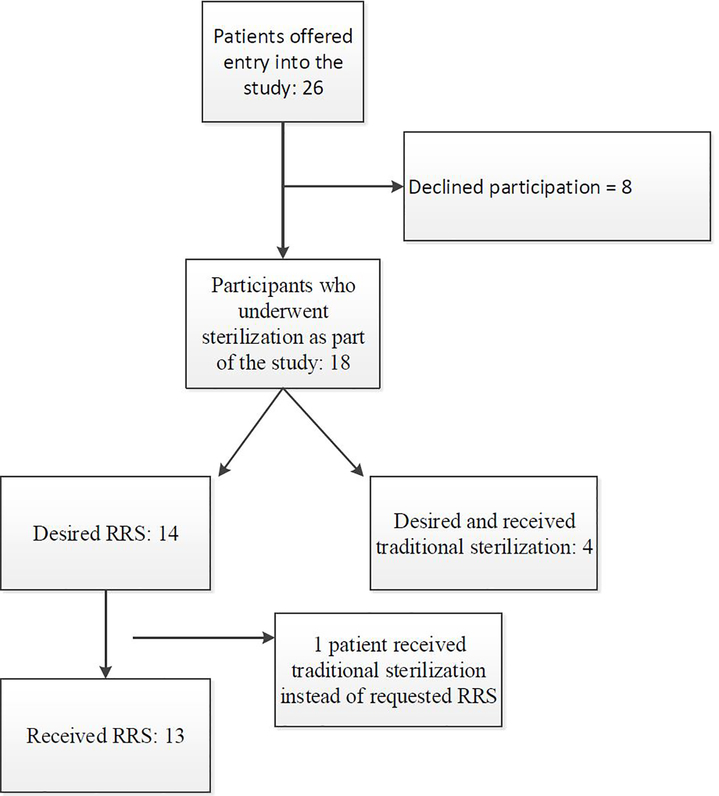

From September 2014 through July 2015, 26 eligible women who requested sterilization were approached, and 18 agreed to be part of the study (Fig.). Of the 18 women, 14 (78%) opted for RRS and 4 opted for traditional sterilization; however, 1 of the women who desired RRS had a tubal occlusion sterilization performed. For the remainder of the analysis, this patient was included in the tubal occlusion sterilization group. In all 13 procedures for which the surgeons intended to perform an RRS, the procedures were successfully completed (Fig.). Participant demographic characteristics and data from historical controls are shown in Table 1.

Fig.

Flow of participants approached for risk-reducing salpingectomy (RRS).

Table 1:

Participant demographic characteristics by sterilization procedure performed

| Characteristic | Risk Reducing Salpingectomy n = 13 | Traditional sterilization via titanium clip, n = 5 | Historical controls n = 22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.0 (5.4) | 34.6 (2.3) | 34.9 (4.7) |

| Parity | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.6 (0.55) | 3.0 (1.0) |

| Race, | |||

| • White | 46% | 40% | 36.4% |

| • Black | 23% | 0% | 13.6% |

| • Othera | 23% | 20% | 18.2% |

| • Missing | 8% | 40% | 31.2% |

| Ethnicity, non-Hispanic | 77% | 80% | 81.8% |

| Insurance status: | |||

| - Medicaid | 39% | 40% | 36.4% |

| - Private | 62% | 60% | 63.6% |

| BMI | 29.5 (8.0) | 28.2 (6.1) | 29.1 (7.1) |

Data represented as means (standard deviations) or percentages. Not all percentages total 100 because of rounding. BMI, body mass index; RRS, riskreducing salpingectomy.

Includes self-reported “other” groups.

Median operating time was longer for the RRS group compared with study (6-minute difference) and historical controls (8-minute difference); however, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). In addition, EBL was not different in comparison with either of the control groups (Table 2). Two (11%) of the 18 subjects (1 in the control group and 1 in the RRS group) reported that they would not recommend RRS to a friend interested in sterilization.

Table 2:

Operating time and estimated blood loss among women who underwent risk-reducing salpingectomy compared to current and historical control groups who underwent laparoscopic sterilization using titanium clips

| Characteristic of operation | Median [IQR] | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Operative time (minutes) | ||

| • RRS (n = 13) | 35 [30–40] | Ref |

| • Study controls (n = 5) | 33 [26–39] | 0.22 |

| • Historical controls (n = 22) | 27 [21–34] | 0.068 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | ||

| • RRS (n = 13) | 5 [5–10] | Ref |

| • Study controls (n = 5) | 7 [5–10] | 0.18 |

| • Historical controls (n = 22) | 10 [5–10] | 0.31 |

IQR, interquartile range; RRS, risk-reducing salpingectomy.

Wilcoxon-rank test as a result of non-normal distribution of the covariates.

There were three intraoperative incidents and all occurred among women who underwent RRS (Table 3), but none of these incidents are considered a major complication as classified by previous reviews of laparoscopic sterilizations.16,17 The only intraoperative complication (a uterine perforation during uterine manipulator placement) was managed with observation during laparoscopy. The RRS was completed without further complication, and the woman was discharged from the surgical recovery room to complete a course of oral antibiotics. One patient undergoing RRS had an uncomplicated procedure, but required overnight observation in the hospital for pain control. No underlying etiology was determined. There were no immediate intraoperative complications in the five women undergoing traditional sterilization. Three of 13 (23%) women undergoing RRS had an unscheduled clinic visit, 2 for incisional pain and 1 for incisional cellulitis without fever (Table 3). With regard to the patient who desired RRS but had a traditional sterilization performed, the decision to perform a traditional sterilization was not made for any surgical or technical reason. In the recovery room, the surgical team explained that a traditional sterilization was completed, and the patient was comfortable with that information. Incorrect allocation is a known complication of research.

Table 3:

List of complications and unscheduled clinic visits from sterilization procedures including procedure performed, description of incident, and final disposition of woman.

| Risk-reducing or traditional sterilization | Description of incident | Final disposition |

|---|---|---|

| Risk- reducing | Intraoperative: uterine perforation during manipulator placement | Observation during laparoscopy, discharged with PO antibiotics |

| Risk-reducing | Intraoperative: patient desired risk-reducing procedure, but surgical team performed traditional sterilization | Patient informed in recovery |

| Risk- reducing | Post-operative: overnight hospitalization for pain control | Patient discharged on POD#1 without additional findings. |

| Risk- reducing | Post-operative: unscheduled clinic visit for pain | Normal post-operative exam. Reassurance provided |

| Risk- reducing | Post-operative: unscheduled clinic visit for incisional redness | Exam diagnosed cellulitis. Patient placed on oral antibiotics |

| Risk- reducing | Post-operative: unscheduled clinic visit for uterine bleeding | Normal post-operative exam. Reassurance provided. |

POD, postoperative day.

Discussion

When our population of women seeking sterilization was educated about sterilization options, the majority chose an RRS. To our knowledge, no other published study has examined the proportion of women choosing RRS when offered a choice of surgical procedures. Unlike other surgical procedures, elective sterilization has unique risks of regret and failure for the reoccurring outcome of pregnancy. Epidemiological research suggests additional cancer-risk reduction of a particular procedure, the RRS.5,6 As surgeons who are obligated to appropriately counsel our patients, we must address the most effective ways to communicate the complexities of this decision with women seeking permanent sterilization. In this study, we piloted a decision aid (see Supplemental Appendix, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A82) that was subjectively beneficial for counseling.

As contraceptive researchers, we want to offer some observations, which are not captured by the data presented. Through this research, we spent hours with women informing them of the risks and benefits of the various methods of sterilization. The decision aid that we developed (Appendix, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A82) provided image and text that facilitated the subsequent discussion. Some counseling pearls are that these discussions take time and often cannot be completed within a single visit. There is a benefit to incorporating partners or close friends or relatives in the decision-making process. Sterilization regret has been a challenge for both women and providers to predict,6 and especially with the irreversibility of RRS, the need for certainty is paramount. With the potential additional benefit from RRS of increased ovarian cancer risk reduction, we found that some women prioritize cancer risk reduction in their decision making, whereas other women prefer a surgical approach with more years of use and outcomes measurement. Other women choose RRS because of the increased contraceptive efficacy. A patient-centered approach that incorporates a discussion of cancer risk, contraceptive failure, and the woman’s previous medical experiences can facilitate the selection of the preferred surgical procedure.

With regard to our specific findings, there has been one published study that compared surgical outcomes between RRS and traditional sterilization.15 The McAlpine et al study included an educational campaign for OBGYN surgeons on the benefits of RRS, and then those educated OBGYNs counseled their patients toward an RRS,15 whereas our study focused on educating the women directly. Another important difference is that the McAlpine et al study included sterilizations performed at the time of cesarean and immediately postpartum in addition to the type of sterilizations included in our study, interval laparoscopic procedures.15 Despite these differences, the two studies reported on some similar surgical outcomes. McAlpine et al reported a significant increase in operating time for RRS compared with traditional sterilization (10 minutes), a finding that we were unable to reproduce.15 Both studies reported no increase in EBL and no increased length of admission, readmission, or transfusion.15

None of the complications in our study resulted in a blood transfusion, conversion to laparotomy, or any other major complication as defined in previous analysis of operative risk in laparoscopic, interval sterilizations.16 There were minor complications in the RRS group that did not result in any serious morbidity, but it is difficult to compare these rates because complications such as unscheduled office visits for pain or nonfebrile cellulitis have not been reported in a large review of sterilization morbidity.17 We stopped recruitment before reaching our recruitment goal because of the safety data reported in the McAlpine et al study15 and the recommendations from the Creinin and Zite editorial.4

In addition, discussions with our colleagues at national and regional meetings demonstrated that RRS was becoming part of routine practice. As such, research equipoise was lost because RRS no longer needs to be offered solely within research studies. In addition to a smaller-than-planned sample size, other limitations include a lack of a randomized design and the fact that our decision aid was never validated. Despite these limitations, our study supports the movement in our field to offer RRS and highlights the importance of a patient-centered approach.

There are a number of important questions that need to be addressed in future research, such as patient age or other demographic factors that should be considered in the consent process for RRS, given the implications of regret; the effect of RRS, if any, on subsequent ovarian function; and the magnitude of ovarian cancer risk reduction from RRS compared with a standard tubal sterilization procedure. Additional research focusing on the patient experience in this complicated decision-making process also would be valuable.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Approximately 600,000 women undergo sterilization in the United States each year, and laparoscopic fallopian tube interruption procedures are the most common. Removing the entire fallopian tube offers increased ovarian cancer risk reduction.

There are additional benefits to removing the entire fallopian tube, including improved sterilization efficacy and reduced ectopic pregnancy risk.

There are additional risks to complete fallopian tube removal, including potential surgical complications and fewer options for women who experience sterilization regret, desiring pregnancy.

Obstetrician/gynecologist surgeons need to be aware of the potential risks and benefits, and patients need to be educated about their options to mutually address this complicated and personal elective procedure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janhvi Rabadey, Samantha Charm, Karen Dorman, Christina Smith, and Lindsey Gangham for their support in recruitment and general study support; Dr Siobhan O’Conner for expertise in tubal pathology; and Drs Amy Bryant, Jamie Krashin, Jessica Morse, and Shanthi Ramesh, who performed counseling and assisted with many of the procedures. In addition, we are appreciative of the patients who agreed to participate.

K.M.D. is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R25CA116339. G.S.S. has received compensation from the Anonymous Foundation, Femasys, Medicines360, and the Society of Family Planning, and is a member of the editorial board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The remaining authors did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

To purchase a single copy of this article, visit sma.org/smj-home. To purchase larger reprint quantities, please contact Reprintsolutions@wolterskluwer.com.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ligasure Instruments, a bipolar tissue sealing device, were donated by the company that manufactures the device, Medtronic (formerly Covidien). The researchers received a grant from Medtronic/ Covidien for the donated devices. Medtronic/ Covidien was not involved in the design, analysis, or publication of this study in any way.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://sma.org/smj-home).

References

- 1.United Nations. World contraceptive patterns 2013. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/family/contraceptivewallchart-2013.shtml. Accessed December 29, 2017.

- 2.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, et al. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. Natl Health Stat Rep 2015;86:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society of Gynecologic Oncology. SGO Clinical Practice Statement: salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. https://www.sgo.org/clinicalpractice/guidelines/sgo-clinical-practice-statement-salpingectomy-forovarian-cancer-prevention. Published November 2013. Accessed December 29, 2017.

- 4.Creinin MD, Zite N. Female tubal sterilization: the time has come to routinely consider removal. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madsen C, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, et al. Tubal ligation and salpingectomy and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and borderline ovarian tumors: anationwide case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lessard-Anderson CR, Handlogten KS, Molitor RJ, et al. Effect of tubal sterilization technique on risk of serous epithelial ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2014;135:423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westhoff C, Davis A. Tubal sterilization: focus on the US. experience. Fertil Steril 2000;73:912–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanner EJ, Long KC, Visvanathan K, et al. Prophylactic salpingectomy in premenopausal women at low risk for ovarian cancer: risk-reducing or risky? Fertil Steril 2013;100:1530–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almog B, Wagman I, Bibi G, et al. Effects of salpingectomy on ovarian response in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization: a reappraisal. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2474–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Findley AD, Siedhoff MT, Hobbs KA, et al. Short-term effects of salpingectomy during laparoscopic hysterectomy on ovarian reserve: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2013;100:1704–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye XP, Yang YZ, Sun XX. A retrospective analysis of the effect of salpingectomy on serum antiMullerian hormone level and ovarian reserve. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:53e1–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morelli M, Venturella R, Mocciaro R, et al. Prophylactic salpingectomy in premenopausal low-risk women for ovarian cancer: primum non nocere. Gynecol Oncol 2013;129:448–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeckxstaens A, Devroey P, Collins J, et al. Getting pregnant after tubal sterilization: surgical reversal or IVF? Hum Reprod 2007;22:2660–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAlpine JN, Hanley GE, Woo MM, et al. Opportunistic salpingectomy: uptake, risks, and complications of a regional initiative for ovarian cancer prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:471e1–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamieson DJ, Hillis SD, Duerr A, et al. Complications of interval laparoscopic tubal sterilization: findings from the United States Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson HB. Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.