Abstract

Facilitating mutually-beneficial educational activities between researchers and school students is an increasingly popular way for research institutes to engage with communities who host health research, but these activities have rarely been formally examined as a community or public engagement approach in health research. The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP) in Kilifi, Kenya, through a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach involving students, teachers, researchers and education stakeholders, has incorporated ‘school engagement’ as a key component into their community engagement (CE) strategy.

School engagement activities at KWTRP aim at strengthening the ethical practice of the institution in two ways: through promoting an interest in science and research among school students as a form of benefit-sharing; and through creating forums for dialogue aimed at promoting mutual understanding between researchers and school students.

In this article, we provide a background of CE in Kilifi and describe the diverse ways in which health researchers have engaged with communities and schools in different parts of the world. We then describe the way in which the KWTRP school engagement programme (SEP) was developed and scaled-up. We conclude with a discussion about the challenges, benefits and lessons learnt from the SEP implementation and scale-up in Kilifi, which can inform the establishment of SEPs in other settings.

Keywords: Community, Public Engagement, health research, schools, science, PAR, scale-up

Background

Community and public engagement with health research is becoming widely acknowledged and described in the literature, and engagement with schools (school engagement) is becoming increasingly adopted by health research institutions as a component of their engagement programmes. Despite this, descriptions of school engagement approaches and their evaluations are rarely described in the academic literature, particularly in low and middle income countries (LMICs), and descriptions of how programmes were initiated and scaled-up are even rarer. We aim to address this gap through providing a description of the 10-year evolution of a School Engagement Programme (SEP) within the context of a large health research institution in Kenya.

The general aims and approaches to community engagement in LMICs

In recent years an increasing emphasis has been placed on the importance of engagement between health researchers and communities who host research 1– 5. Community engagement (CE) with health research comes in a range of shapes and forms, and has a range of, sometimes conflicting goals, often addressing ethical principles of research 6. These goals comprise 7:

Broadly protecting communities in research

Minimising possible exploitation

Increase the likelihood that research will generate fair benefits locally

Ensure awareness and respect for local cultural differences

Ensure respect for recruited participants and study populations

Legitimacy of engagement process

Partners share the responsibility of research

Minimise community disruption

Ensure that disparities, inequalities and stigma are not inadvertently replicated or reinforced

It is perhaps unsurprising that this range of goals have spawned several approaches to engaging host communities with health research. In Africa, in an attempt to address these goals, researchers and CE practitioners have engaged communities in a range of ways, including: ‘town-hall’ meetings with communities or stakeholders; focus group discussions; community advisory boards and deliberative sessions 8.

The KEMRI-WT programme in Kenya

The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme ( KWTRP) is a well-funded health research programme, that was established in the rural coastal town of Kilifi, in Kenya in 1989, as a collaboration between the Kenyan Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), the Wellcome Trust and the University of Oxford. Historically the focus of the KWTRP was on malaria research, but since 1989 the Programme has expanded substantially both in terms of research focus, diversifying to include basic biological research with clinical trials, epidemiology, social and behavioural sciences and health systems and policy research, and in geographical scope, establishing hubs in Nairobi, Kenya, and Mbale in Uganda. In early 2017 KWTRP employed 800 staff, in the Kilifi and Nairobi hubs, mostly Kenyan, but with a few research staff from other African countries and other parts of the world. The main hub of the KWTRP located in Kilifi town, the administrative capital of Kilifi County situated some 60km north of Mombasa, comprises training and administration facilities and state of the art biomedical laboratories.

The centre aims to: “Conduct research to the highest international scientific and ethical standards on the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the region, in order to provide the evidence base to improve health”; and “Train an internationally competitive cadre of Kenyan and African research leaders to ensure the long term development of health research in Africa”. By December 2018, the KWTRP had produced 103 completed PhDs, with many of these researchers currently employed as post-doctoral students and principal investigators in the programme and beyond.

Juxtaposed with this research wealth and hub of opportunities for further education are the educational and resource challenges faced by local communities in Kilifi County. Kilifi County, one of Kenya’s 47 administrative counties, is among Kenya’s ‘20 most marginalised counties’ 9, with 64% of its residents living in dwellings with earth floors. The County’s residents are mainly dependent on agriculture, tourism and fishing for employment and food 10, and 36% of Kilifi residents have no formal education, with only 13% having secondary school education and above, compared to 25% and 23% respectively across Kenya 11. Much of the epidemiological and clinical research conducted within the programme is underpinned by the Kilifi Heath and Demographic Surveillance System ( KHDSS), which collects demographic information about a population of 280,000 within a geographically defined area of 900km2, through regular visits to residential homesteads.

CE at the KWTRP

In the early 2000s, a consultative process was embarked upon, drawing on inputs from local and international community and research stakeholders, to establish a communication strategy for the programme 12 aimed at strengthening communication and building mutual understanding between researchers and residents of the Kilifi KDHSS. For practical purposes, the KWTRP’s communication strategy defined ‘the community’ as the residents living within the KHDSS where the majority of the KWTRP’s research activities have been conducted 12.

CE in Kilifi has been divided into two broad mutually supportive components: study specific; and programme-wide engagement 6. Study specific engagement is aimed at addressing the range of communicational and engagement requirements of specific research studies, such as providing specific trial/study information to communities to support informed consent 13– 15 and disseminating specific research findings 16. Programme-wide engagement aims at addressing a broader range of ethical goals which cut across a range of studies, institutional practice and policy, and the basic principles of research. For example, programme-wide engagement activities have included strengthening the community’s understanding of research and gaining community feedback about institutional policies 6. Until 2010, engagement approaches have comprised community and stakeholder meetings; focus group discussions; deliberative sessions; open-days; and regular meetings with a network of 170 KEMRI Community Representatives elected by the community 12, 17– 21.

In 2005 there were 4 full-time staff employed to implement the CE strategy and by 2018 the team had grown to 20 staff making up what is now referred to as the community liaison group (CLG). The CLG coordinates and implements all programme-wide engagement at KWTRP and supports study-specific activities. The group draws on support from four senior social scientists.

From the outset, during open days and meetings, community members frequently requested a school engagement element to the work, specifically to provide careers advice and motivation to secondary school students wishing to pursue medical and scientific careers 22. In 2010, we initiated our school engagement work piloting our approach with three local secondary schools. In the following sections, we first provide an overview of the international experience and approaches to engaging school students with health research. We then go on to share our own experience, which evolved in parallel to many of the approaches described. Finally, we conclude with some key elements across the Kenyan experience which offer key considerations for future similar projects.

International experience of school engagement

Engagement between researchers and schools

Motivated by the growing evidence of the influence of ‘out-of-school-science’ in promoting positive attitudes towards science among school students 23– 26, and the need to engage with a range of community members, health researchers worldwide have sought several ways of engaging with local schools. A common theme for many school engagement with science approaches is that they anticipate that students will adopt scientists as role-models to look up to and emulate 27– 33. The adoption of science role-models in turn, has the potential to: inspire student career choices; challenge stereotypical perceptions of scientists; provide realistic insights into real-world science 30; and support science teachers to maintain students’ interest in the pursuit of science 27. Several initiatives 28, 29, 31, 32 have drawn inspiration from the ‘possible selves’ theory 34. In this theory, as children grow, their career aspirations develop as a result of their exposure to different careers, and influential individuals within careers. The breadth of children’s repertoire of possible future careers (or possible selves) can be widened when exposure to specific careers enables a belief that they are capable of achieving this career. Angela Porta 31, for example, reported that encounters with female biomedical researchers from diverse ethnic backgrounds challenged students’ stereotypical preconceptions of scientists, whilst other studies reported that interactions with scientists influenced their desire to become a scientist and promoted positive attitudes towards science 28, 29, 32.

Engagement between health researchers and schools has focussed mainly on educational goals, including: promoting an interest in health, science and science related careers; promoting science role models; promoting positive attitudes towards science; and de-mystifying science and scientists 35– 38. Less emphasis has been placed on CE goals such as: promoting an awareness of research; and feeding unique student perspectives into research implementation 39– 43; or a combination of both educational and CE goals 22, 39.

Approaches for engagement between health researchers and schools can be classified into four main types 39: a) School-Scientist partnerships, which have been popular in Australia, New Zealand and the USA since the 1980s, and involve scientists spending periods of time at schools (often several years) conducting activities aimed at promoting an interest in, and positive attitudes towards science, and in some cases collecting scientific data 37, 44– 47; b) Science work-experience attachments, where students spend extended periods attached to researchers at research institutions, learning about research careers and ‘science citizenry’ 35, 48– 50; c) Young Persons Advisory Groups, which consist of regular meetings between health researchers and groups of 10–15 school children, aimed at discussing and advising on research questions, procedures, implementation, disseminating of findings and the appropriateness of language and content of informed consent forms 41– 43; and d) Short encounters between researchers and schools, usually conducted through one-day (or less) events.

Several universities and science research institutes have reported on their experience with facilitating short, often one-day, interactions between researchers and school students. A prominent set of activities involves inviting school students to institutions to meet scientists and see laboratories 22, 40, 51, 52, or to attend open days comprising science demonstrations facilitated by scientists 53. An alternative approach in the USA is the ‘Scientists In Classrooms’ (Fitzakerley, Michlin 54 where neuroscientists enter classrooms to provide a 40–60-minute talk about their work aiming to promote neuroscience literacy and positive attitudes towards neuroscience. All these approaches are broadly aimed at raising an interest in science, demystifying the work of scientists, and raising awareness of research.

In Africa, there are a growing number of science centres targeting audiences of school students, particularly in Southern Africa 55. Of note is the SAASTEC programme (The Southern African Association of Science and Technology Centres), linked to South African Universities, which has initiated a network of Science Centres aimed at enhancing school students experience of learning science. The focus of these centres however, is a much broader engagement with science, as opposed to health research. Narrowing down to a focus on health research, several African research institution websites describe different engagement activities with local schools. Examples include: the MRC in The Gambia describe hosting school students to their centre; H3 Africa have an on-line platform where students can ask questions to scientists; and a South African project engages primary school students with health and research through popular music. However, despite this growth in engagement activities, published articles describing the purpose of such engagement, and evaluations of the outcomes of engagement between health research and schools in Africa, is restricted to less than a handful 22, 39, 56.

Researcher gains from school engagement

Several studies describe factors that make school engagement challenging to researchers, for example having to work within the constraints of the school timetable 37, 44, 57, generally negative perceptions of engagement 58 and a common perception among scientists that engagement is done by those who are not good enough for science careers 58– 60. Contrary to the latter belief, a study involving data from 11,000 scientists, found a statistically significant correlation between public engagement activity and academic output 59. The authors of this study argue that dissemination activities (including popularisation of science in schools) do not compete with academic achievement, but the two are mutually supportive, contributing to a broadening of scientists’ horizons and generating new perspectives and ideas for research.

Descriptions of engagement between researchers and schools, report that participating scientists gained satisfaction and enjoyment from promoting science 37, 47, 52, 61 and that it contributed positively to their communication skills 22, 37, 47, 52, 61. Researchers have reported that engagement can offer insights into the context in which they work 22, 37, 44, 62, an appreciation of the challenges of working with schools including the heavy workloads of teachers 37, 44, and a better understanding of community knowledge of and attitudes towards their research 22, 47, 61. In Kenya, a low-income country, researchers reported that participating in school engagement offered them an opportunity to ‘give back’ to the community and contribute to local development through promoting science education 22. Engagement leading to gains in researchers’ appreciation of local concerns about research in LMICs has been highlighted as important, to inform better and more ethically sound research designs and implementation 63. With respect to engaging school students, the recent emergence of Young Persons’ Advisory Groups underscores the view that young people and adolescents have unique insights which can feed into research planning and implementation.

Methodological approach to establishing a School Engagement Programme at KWRTP

Establishing a School Engagement Programme (SEP) in Kilifi was motivated by two factors. Firstly, by frequent requests by community leaders, for support in local schools: ‘What is KWTRP doing to advise our schoolchildren on what subjects to choose to become scientists?’ (Roka village chief, annual debriefing workshop, 25 October 2007 cited in Davies, Mbete 22). The second motivation came from KWTRP researchers’ desire to draw on its existing human and laboratory resources to enhance local students’ educational experiences and provide opportunities to and learn about science 22, 64. The latter acknowledged the relative wealth and resource disparity between the state-of-the-art research institution and local public secondary schools, often characterised as having large class-sizes, poorly resourced laboratories 65, 66 and infrequent opportunities for students to conduct practical science 65. School science education, not only in Kenya, but generally, often presents an abstract and artificial depiction of ‘real-world’ science where everything takes place in the confines of the school laboratory 23, 24. In poorly-resourced LMIC school laboratories with limited opportunities for experiments and observations, this abstractness is likely to be heightened. Based on the potential for “out-of-school” science experiences, (e.g. field visits) to contribute to more “authentic” school science 23, we felt that exposure to Kenyan scientists and locally conducted research, could benefit students through promoting an interest in, and positive attitudes towards school science, which could ultimately lead to improved school science achievement 67– 70. Benefitting school students in this way, combined with raising an understanding of locally conducted research aimed at addressing the ethical principles of research outlined in the Belmont Report 71; beneficence, justice, and respect for persons.

Whilst raising students’ interest in science and research related careers, it was felt that engaging schools presented a further opportunity to extend engagement with the broader community. Engaging with school students, though potentially important in its own right as described above, was also based on a premise that if young people can influence peer and family health-related beliefs and behaviour 72– 76, when exposed to researchers, they may be provided with opportunities to re-evaluate prevailing community knowledge, misconceptions, beliefs and attitudes related to health research, and influence community attitudes based on a fuller understanding of research.

A participatory action approach to establishing a SEP

In 2008, the Wellcome Trust’s International Engagement Award provided funding to pilot a SEP as part of the KWTRP CE activities 64. A participatory action research (PAR) process was used from the outset to initiate and develop the SEP incorporating the views, ideas and needs of students, teachers, parents, county education officers and researchers. A PAR approach was chosen because of its strength in engaging the voices, perspectives and experiences of all the participants and researchers involved 77, 78. According to Baum, MacDougall 79 PAR “focuses on research whose purpose is to enable action. Action is achieved through a reflective cycle, whereby participants collect and analyse data, then determine what action should follow. The resultant action is then further researched and an iterative reflective cycle perpetuates data collection, reflection, and action as in a corkscrew action.” The development of the Kilifi SEP involved three cycles of PAR over a ten-year period, each entailing: brain storming and planning meetings with researchers, teachers, students and county education office staff; implementation and evaluation; and feedback/reflection sessions. The learning gained from each cycle fed into the planning and implementation of subsequent PAR cycles. Guiding this process was a shared understanding among the participants that the school engagement programme should be aimed at addressing both educational as well as engagement goals, specifically: promoting mutual understanding between researchers and the community; nurturing respect for the community among researchers; promoting an interest in and positive attitudes towards science and science related careers among students (as a means of benefit sharing); and raising awareness of locally conducted research 22.

PAR cycle 1: 2009 – 2010

Developing the initial pilot SEP activities in 2009 involved convening separate group discussions with teachers and students from three schools, and researchers, in order to assess willingness and gather ideas for engagement. Information and ideas from these discussions were then compiled and fed into an initial 2-day workshop involving teachers and researchers. At the time, based on a consensus between teachers, researchers and education office staff, students were not included in this workshop, because it was felt that their free communication would be hindered by the presence of teachers and participating researchers (this decision was revised to include students in the second and third PAR cycles). The 2009 workshop comprised three components: a) learning about research through a KWTRP tour and interactive activities with researchers; b) brainstorming potential engagement activities; and c) ranking the brainstormed ideas, based on their perceived value for students and implementability. The school engagement activities developed through this process were implemented in the three participating schools between May and August 2009 and comprised: school visits to KWTRP for a lab tour and interactive sessions with researchers; researcher visits to schools to give careers talks; and science-based competitions for students. An evaluation of this pilot programme, using mixed methods including: pre and post intervention student surveys; focus group discussions; and in-depth interviews with students, teachers and education officers, found that the activities promoted a better understanding of, and positive attitudes towards, health research and school biology among students 22. Further, the activities were well-received by parents, teachers and education officers, and that engagement provided researchers with an appreciation of the context in which they worked 22. During feedback meetings with teachers, the findings of the evaluation were combined with teacher and researcher experiences to inform the development of further ideas for engagement. These ideas were implemented in the second PAR cycle of the SEP’s development.

PAR cycle 2: 2010 – 2012

Following the success of the initial two years of the SEP, the Wellcome Trust provided funding for a continuation of activities from 2011 to 2012. The second PAR cycle incorporated feedback and reflection from the first PAR cycle into a new series of brainstorming and planning discussions with teachers, researchers and students. This enabled: the scale-up of the SEP to five secondary schools, the inclusion of activities to support school science clubs in preparation for the national School Science and Engineering Fair (SEF) competition; and the establishment of a 3-month attachment scheme at KWTRP for nine top-performing school leavers from Kilifi County per year.

In 2012, SEP activities involved an estimated 1000 students visiting the KWTRP for engagement activities, with more students interacting with researchers through researcher visits to schools to give career and inspirational talks.

PAR cycle 3: 2013 – 2017

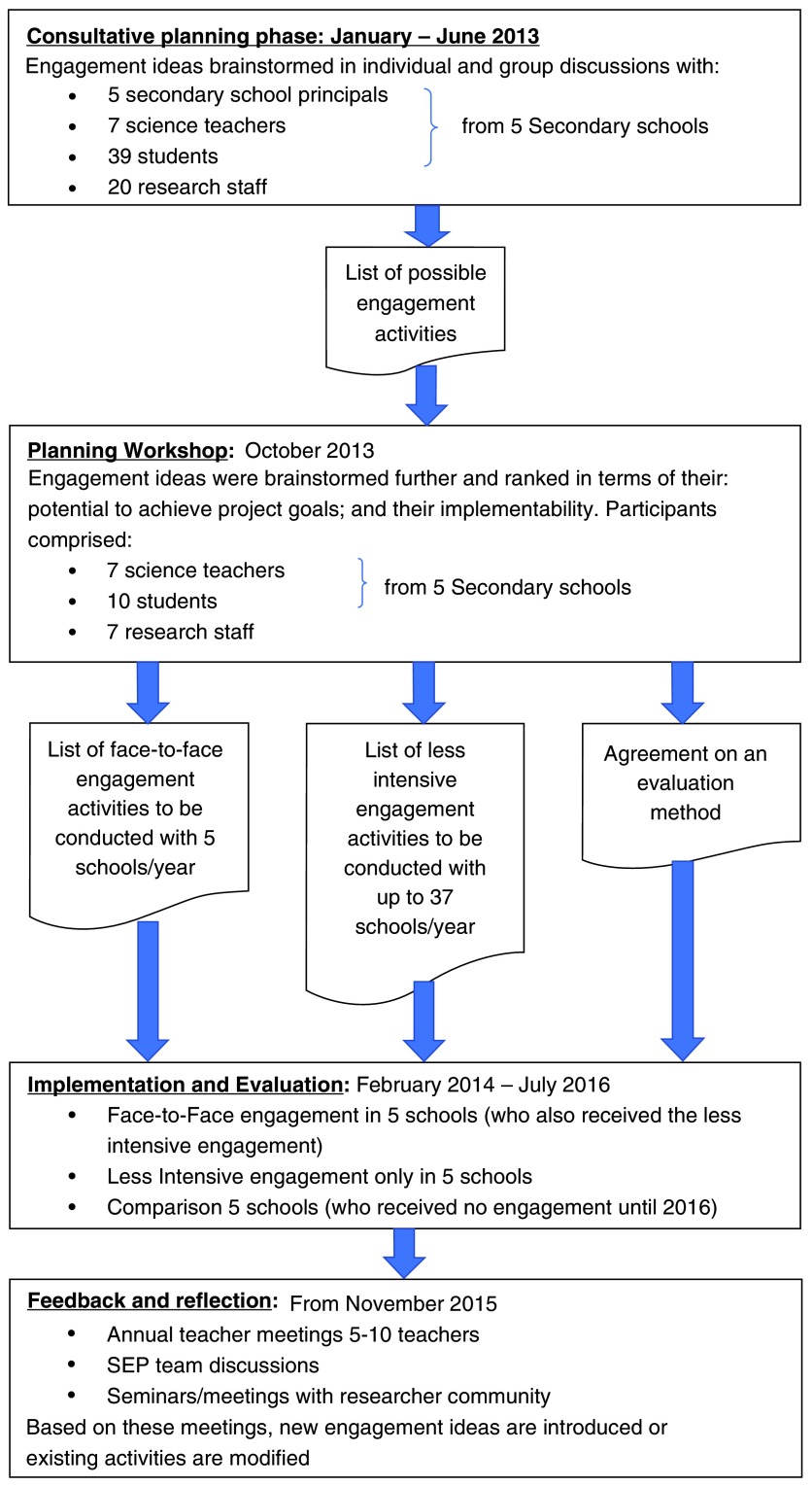

Based on the findings of the pilot evaluation (Davies, Mbete et al. 2012), participant feedback and reflections on PAR cycles 1 and 2, a demand for inclusion from other schools in Kilifi County, and a desire among the KWTRP’s CLG to scale-up engagement with all 37 state secondary schools across the KDHSS area, a third round of funding was acquired from the Wellcome Trust’s International Engagement Award 80. Scaling up the SEP to 37 schools raised two main constraints: a) the limited number and time of researchers to engage with schools; and b) the limited capacity of the KWTRP laboratories to host visiting school groups without excessively disrupting the day-to-day research activities. In 2013 a third cycle of PAR was conducted to help ensure that the expansion was planned in a way that supported effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability from both school and research stakeholders’ perspectives. This process is described in Figure 1 below and resulted in two broad approaches for engagement: a) concentrated face-to-face engagement with 5–6 schools per year on a rotational basis using engagement activities developed between 2008 – 2012; and b) a less-intensive engagement with activities which could be conducted with 37 schools. These activities are summarised in Table 1 below. A component of the less intensive engagement was web-based. Students with internet access could engage with research through an interactive SEP website, which documents SEP activities, provided science resources and introduces students to a range of research staff, and through an on-line engagement programme called “I’m a scientist get me out of here” (IAS). Over the two-week IAS implementation period in 2014, an estimated 200 students from 10 schools asked 5 participating scientists nearly 500 questions related to science and health. The site received over 10,000 hits over the event. Between 2014 and 2018, these face-to-face and less-intensive engagement activities were rolled out over a total of 37 schools and evaluated using a mixed method approach, and this is described elsewhere 39.

Figure 1. Phase 3 of the PAR cycle.

Table 1. Summary of school engagement programme activities conducted between 2015–2017.

| Concentrated face-to-face engagement

5–6 different schools a year |

Less Intensive engagement

37 schools a year |

|---|---|

| 1. Form 1 & 2 student KWTRP lab tour and interactive sessions with

research staff 2. Science club visits to KWTRP – students present SEF projects to researchers’ and receive feedback 3. Scientist visits to schools to discuss research and their careers. 4. Inclusion in Engagement B activities |

1. On-line engagement through:

• The IAS platform • The KWTRP-SEP website 2. Annual Science Symposium (quiz) for teams of 4 students from 37 schools |

As well as developing and agreeing on new approaches and activities for engagement, workshop participants were able to contribute ideas towards evaluating the activities. The evaluation, described elsewhere (manuscript in preparation), enabled further reflection among the SEP team, teachers and researchers, and this continuing cycle enables the SEP to be responsive to the needs of the participants.

SEP activities are voluntary for schools with all costs covered by the KWTRP. The decision by the school principal to allow their school to participate in individual SEP activities is influenced by several factors. These factors include: school participation in other extracurricular activities; time pressure for teachers to complete specific subject syllabi; and specific to IAS participation, the availability of computers and internet connectivity in the school. Though resources in Kenyan Secondary schools are limited 65, in 2006 the government of Kenya launched a schools Information Technology policy 81 and access to computers has grown steadily in schools through the support of several international partners 82. In 2014 IAS, was not accessible to all schools, however this is likely to improve in the future if the Kenya government adheres to its commitment to improve ICT infrastructure in schools and equip students with IT skills 83.

Discussion

This paper has provided an overview of the ways in which researchers have engaged with schools, and a description of how a PAR approach involving researchers, teachers, students and county education officers was used to establish the SEP at KWTRP in Kilifi, Kenya. The PAR approach generated a programme of activities facilitating engagement and interaction between KWTRP researchers and students and guided the scale-up of the programme from 3 to 37 local secondary schools. Combining two approaches for engaging schools enabled a ‘concentrated engagement’ on a rotational basis with 5 school per year, whilst maintaining contact with 32 schools through ‘less-intensive engagement.’ Over a 6-year period between 2012 and 2018 an estimated 1000 students per year from 37 schools have participated in ‘concentrated face-to-face engagement’ and an additional 2000 students participated in ‘less-intensive engagement’ per year in 2017 and 2018. Further, on-line engagement has enabled the extension of engagement to schools beyond Kilifi, in Nairobi, Nakuru and Kisumu.

Clearly establishing a SEP cannot rely solely on the goodwill of researchers, teachers and research institutions, it requires funding to sustain the activities, particularly in a context where schools have very little resources to support out-of-school activities. From 2009–2017, the Kilifi SEP has depended on the support of two extended Wellcome Trust International Engagement Awards worth £316,000 which has supported team salaries (one coordinator and two Community Liaison officers) and all school activities. Based on the success of the programme and continued support from the Kilifi County Education Office and the Wellcome Trust, the SEP secured funding for 5 years to expand the programme between 2017–2021.

The co-planned and co-implemented activities aimed at combining educational goals with goals of community engagement. At the outset it was envisioned that interactions between students and researchers would: nurture students’ interest in science, awareness of science related careers, and understanding of locally conducted health research; whilst researchers would gain valuable insights into community views, which would in turn, nurture a respect for the community hosting KWTRP’s research. Clearly, exploring whether these goals have been met requires rigorous evaluation (described elsewhere), however, demand for inclusion and continued participation from 37 schools and research staff, and continued support from the Kilifi County Education office, would suggest that at the very least, schools and researchers perceive the SEP activities to be beneficial. Reflecting on the demand for, and continued support for the SEP, implementing staff felt that including teachers, students and researchers in a PAR process, nurtured participant ‘buy-in’ and contributed to the activities’ appropriateness and uptake.

Tindana, Singh 5 describe how forming ‘authentic partnerships’ through CE can generate mutual benefits, or ‘win-win’ outcomes for researchers and communities. The importance of engagement generating mutual benefits has been re-enforced in more recent literature, see for example the report of the Participants in the CE and Consent Workshop 6. Arguably, what sets school engagement apart from other forms of CE is its unique potential for generating ‘win-win’ outcomes for participating researchers and students: as students get opportunities to learn about science and related careers, researchers gain from gaining valuable insights from school students, which can potentially be incorporated into research implementation 84 and an understanding of the context in which they work 22. The type of inferred benefits accrued through engagement, as experienced through the SEP, can create demand for further engagement among schools and researchers, thus enabling further opportunities to address CE goals. In this way, school engagement becomes ‘demand-driven’ as opposed to some other forms of potentially ‘supply driven’ engagement, with a greater focus on, for example, providing information about research for recruitment.

Whilst demand for inclusion from schools highlights perceived potential benefits, meeting this demand with limited resources can be challenging, and where the demand cannot be met, schools can potentially feel excluded or left-out. Finite funding resources can influence engagement practitioners’ decision to either opt for a greater depth of face-to-face, and arguably higher quality engagement with fewer schools, or to widen the outreach to a larger number of schools with shallower engagement 85. At KWTRP, our PAR approach has resulted in a compromise between the two positions, combining a greater depth of engagement with 5–6 schools per year, with less-intensive engagement with up to 37 schools. Our experience is that though schools often feel disappointed to shift from the annual rota of the 5–6 face-to-face schools, the disappointment is lessened through an opportunity for continued participation in less-intensive school engagement. The approach also enables the SEP team members to maintain contact with all schools as the rotation proceeds.

Hyder, Krubiner 86 argue that the longer a research institution works in a community, the greater the obligation for researchers to ensure greater benefits for host communities. However, they limit their discussion to benefitting communities through improving health infrastructure and boosting local economies through their presence in the community. The evolution of, and the demand for the SEP in Kilifi has shown that health research Institutions such as the KWTRP can draw from their existing human and science resources to benefit local schools through enhancing students’ science education experiences. As more KWTRP studies depend on schools for studying health and diseases, for example Abubakar, Kariuki 87 and Brooker, Okello 88, there may be a case for increasing benefits to local schools as a means of addressing of long-term community benefits. The experience of establishing a SEP suggests that engagement programmes such as the SEP can become spaces where community members are empowered to negotiate the terms and benefits of engagement and create mutually-beneficial initiatives.

Conclusion

School engagement offers opportunities to draw from existing health research resources to benefit both researchers and schools. The benefits of engagement perceived by schools can create a demand for further and wider engagement which can ultimately contribute to the sustainability of SEPs. In our experience, including researchers, teachers and students in the design and implementation of school engagement through a PAR approach, can ensure that activities are responsive to participant views and locally appropriate.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Publication in Wellcome Open Research does not imply endorsement by Wellcome.

Data availability

No data is associated with this article.

Acknowledgments

Establishing a SEP in Kilifi has depended on the enthusiasm and ideas of students, teachers, and researchers and has been supported by the Kilifi education office. We are very grateful for this support. Much of the information contained in this paper forms the background from Alun Davies’ Ph.D. 39, and as such replicates some of the information contained in that document. Lastly, the authors would like to thank the Director of Kenya Medical Research Institute for granting permission to publish this work.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Wellcome [100602]; [086249]; [203077].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 3 approved]

References

- 1. Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Killen J, et al. : What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(5):930–937. 10.1086/381709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Quinn SC: Ethics in public health research: protecting human subjects: the role of community advisory boards. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):918–922. 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benatar SR: Reflections and recommendations on research ethics in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(7):1131–41. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00327-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman PA: Towards a science of community engagement. Lancet. 2006;367(9507):302. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68067-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tindana PO, Singh JA, Tracy CS, et al. : Grand challenges in global health: community engagement in research in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e273. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Participants in the Community Engagement and Consent Workshop, Kilifi, Kenya, March 2011: Consent and community engagement in diverse research contexts. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2013;8(4):1–18. 10.1525/jer.2013.8.4.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacQueen KM, Bhan A, Frohlich J, et al. : Evaluating community engagement in global health research: the need for metrics. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(1):44. 10.1186/s12910-015-0033-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tindana P, de Vries J, Campbell M, et al. : Community engagement strategies for genomic studies in Africa: a review of the literature. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(1):24. 10.1186/s12910-015-0014-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CRA CoRA: Creating a County Development Index to Identify marginalised Counties. In CRA Working Paper.2012. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10. ASDSP: Agricultural Sector Development Support Programme, Republic of Kenya.2016; [cited 2016 26/07/2016]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ngugi E, Kipruto S, Samoei P: Exploring Kenya’s Inequality: Pulling Apart of Pooling Together. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and Society for International Development.2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marsh V, Kamuya D, Rowa Y, et al. : Beginning community engagement at a busy biomedical research programme: experiences from the KEMRI CGMRC-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):721–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Angwenyi V, Kamuya D, Mwachiro D, et al. : Complex realities: community engagement for a paediatric randomized controlled malaria vaccine trial in Kilifi, Kenya. Trials. 2014;15(1):65. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Angwenyi V, Kamuya D, Mwachiro D, et al. : Working with Community Health Workers as 'volunteers' in a vaccine trial: practical and ethical experiences and implications. Dev World Bioeth. 2013;13(1):38–47. 10.1111/dewb.12015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marsh VM, Kamuya DM, Mlamba AM, et al. : Experiences with community engagement and informed consent in a genetic cohort study of severe childhood diseases in Kenya. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11(1):13. 10.1186/1472-6939-11-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gikonyo C, Kamuya D, Mbete B, et al. : Feedback of research findings for vaccine trials: experiences from two malaria vaccine trials involving healthy children on the Kenyan Coast. Dev World Bioeth. 2013;13(1):48–56. 10.1111/dewb.12010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jao I, Kombe F, Mwalukore S, et al. : Research Stakeholders' Views on Benefits and Challenges for Public Health Research Data Sharing in Kenya: The Importance of Trust and Social Relations. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0135545. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kamuya DM, Marsh V, Kombe FK, et al. : Engaging communities to strengthen research ethics in low-income settings: selection and perceptions of members of a network of representatives in coastal Kenya. Dev World Bioeth. 2013;13(1):10–20. 10.1111/dewb.12014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marsh V, Kombe F, Fitzpatrick R, et al. : Consulting communities on feedback of genetic findings in international health research: sharing sickle cell disease and carrier information in coastal Kenya. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14(1):41. 10.1186/1472-6939-14-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molyneux S, Mulupi S, Mbaabu L, et al. : Benefits and payments for research participants: experiences and views from a research centre on the Kenyan coast. BMC Med Ethics. 2012;13:13. 10.1186/1472-6939-13-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Njue M, Molyneux S, Kombe F, et al. : Benefits in cash or in kind? A community consultation on types of benefits in health research on the Kenyan Coast. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127842. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davies A, Mbete B, Fegan G, et al. : Seeing ‘With my Own Eyes’: Strengthening Interactions between Researchers and Schools*. IDS Bull. 2012;43(5):61–67. 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00364.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braund M, Reiss M: Towards a more authentic science curriculum: the contribution of out-of-school learning. Int J Sci Educ. 2006;28(12):1373–1388. 10.1080/09500690500498419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braund M, Reiss M: Validity and worth in the science curriculum: learning school science outside the laboratory. Curriculum J. 2006;17(3):213–228. 10.1080/09585170600909662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Falk J, Dierking L: Learning from museums - Visitor experiences and the making of meaning. Plymouth: AltaMira Press.2000. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pedretti EG: Perspectives on learning through research on critical issues-based science center exhibitions. Sci Educ. 2004;88(S1):S34–S37. 10.1002/sce.20019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aschbacher PR, Li E, Roth EJ: Is science me? High school students' identities, participation and aspirations in science, engineering, and medicine. J Res Sci Teach. 2010;47(5):564–582. 10.1002/tea.20353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mills LA: Possible Science Selves: Informal Learning and the Career Interest Development Process. International Association for Development of the Information Society. 2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mills LA, Katzman W: Examining the Effects of Field Trips on Science Identity. International Association for Development of the Information Society. 2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pleiss MK, Feldhusen JF: Mentors, role models, and heroes in the lives of gifted children. Educ Psychol. 1995;30(3):159–169. 10.1207/s15326985ep3003_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Porta AR: Using diversity among biomedical scientists as a teaching tool: A positive effect of role modeling on minority students. Am Biol Teach. 2002;64(3):176–182. 10.1662/0002-7685(2002)064[0176:UDABSA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith WS, Erb TO: Effect of women science career role models on early adolescents' attitudes toward scientists and women in science. J Res Sci Teach. 1986;23(8):667–676. 10.1002/tea.3660230802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zirkel S: Is there a place for me? Role Models and Academic Identity among White Students and Students of Color. Teach Coll Rec. 2002;104(2):357–376. 10.1111/1467-9620.00166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Markus H, Nurius P: Possible selves. Am Psychol. 1986;41(9):954–969. 10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gervassi AL, Collins LJ, Britschgi TB: Global health: a successful context for precollege training and advocacy. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13814. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rennie LJ: Learning science outside of school. Handbook of research on science education. 2007;1 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rennie LJ, Heard MR: Scientists in Schools: Benefits of Working Together. In 2nd International STEM in Education Conference.Beijing, China.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woods-Townsend K, Bagust L, Barker M, et al. : Engaging teenagers in improving their health behaviours and increasing their interest in science (Evaluation of LifeLab Southampton): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:372. 10.1186/s13063-015-0890-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davies AI: Expectations, Experiences and Impact of Engagement Between Health Researchers and Schools in Kenya.The Open University.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 40. France B, Bay JL: Questions Students Ask: Bridging the gap between scientists and students in a research institute classroom. Int J Sci Educ. 2010;32(2):173–194. 10.1080/09500690903205189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kirby J, Tibbins C, Callens C, et al. : Young People's Views on Accelerometer Use in Physical Activity Research: Findings from a User Involvement Investigation. ISRN Obes. 2012;2012:948504. 10.5402/2012/948504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lythgoe H, Price V, Poustie V, et al. : NIHR Clinical Research Networks: what they do and how they help paediatric research. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(8):755–759. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thompson H, Frederico N, Smith SR, et al. : iCAN: Providing a Voice for Children and Families in Pediatric Research. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49(5):673–679. 10.1177/2168479015601344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Falloon G: e-science partnerships: Towards a sustainable framework for school–scientist engagement. J Sci Educ Technol. 2013;22(4):393–401. 10.1007/s10956-012-9401-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cripps Clark J, Tytler R, Symington D: Bringing authentic science into schools. Teaching Science: The Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association. 2014;60(3):28–34. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 46. Howitt C, Rennie L: Science has changed my life! evaluation of the scientists in schools project (2008–2009). Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. ACT: CSIRO Education.2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tytler R, Symington D, Williams G, et al. : Building Productive Partnerships for STEM Education.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bell RL, Blair LM, Crawford BA, et al. : Just do it? Impact of a science apprenticeship program on high school students' understandings of the nature of science and scientific inquiry. J Res Sci Teach. 2003;40(5):487–509. 10.1002/tea.10086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gibson HL, Chase C: Longitudinal impact of an inquiry‐based science program on middle school students' attitudes toward science. Sci Educ. 2002;86(5):693–705. 10.1002/sce.10039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Knox KL, Moynihan JA, Markowitz DG: Evaluation of short-term impact of a high school summer science program on students' perceived knowledge and skills. J Sci Educ Technol. 2003;12(4):471–478. 10.1023/B:JOST.0000006306.97336.c5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Grace M, Woods-Townsend K, Griffiths J, et al. : Developing teenagers' views on their health and the health of their future children. Health Educ. 2012;112(6):543–559. 10.1108/09654281211275890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Woods-Townsend K, Christodoulou A, Rietdijk A, et al. : Meet the Scientist: The Value of Short Interactions Between Scientists and Students. Int J Sci Educ Part B. 2016;6(1):89–113. 10.1080/21548455.2015.1016134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Greco SL, Steinberg DJ: Evaluating the Impact of Interaction between Middle School Students and Materials Science and Engineering Researchers. In MRS Proceedings.Cambridge Univ Press.2011;1364 10.1557/opl.2011.1180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fitzakerley JL, Michlin ML, Paton J, et al. : Neuroscientists’ classroom visits positively impact student attitudes. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84035. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Persson P: Science centres–a global movement. European network of science centres and museums newsletter.2010;83(1). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gooding K, Makwinja R, Nyirenda D, et al. : Using theories of change to design monitoring and evaluation of community engagement in research: experiences from a research institute in Malawi [version 1; referees: 3 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:8. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.13790.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wormstead SJ, Becker ML, Congalton RG: Tools for successful student–teacher–scientist partnerships. J Sci Educ Technol. 2002;11(3):277–287. 10.1023/A:1016076603759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ecklund EH, James SA, Lincoln AE: How academic biologists and physicists view science outreach. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36240. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jensen P, Rouquier JB, Kreimer P, et al. : Scientists who engage with society perform better academically. Sci Public Policy. 2008;35(7):527–541. 10.3152/030234208X329130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. The Royal Society: Science Communication: Survey of Factors affecting Science Communication by Scientists and Engineers. London.2006. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rennie L, Howitt C: "Science has changed my life!" evaluation of the scientists in schools project (2008–2009). Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, (ACT: CSIRO Education).2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 62. O’Daniel JM, Rosanbalm KD, Boles L, et al. : Enhancing geneticists' perspectives of the public through community engagement. Genet Med. 2012;14(2):243–249. 10.1038/gim.2011.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tindana PO, Rozmovits L, Boulanger RF, et al. : Aligning community engagement with traditional authority structures in global health research: a case study from northern Ghana. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1857–67. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Davies A, Kamuya D: WT086249AIA Engaging School Communities with Health Research and Science in Kilifi District, Kenya.Wellcome Trust International Engagement Award.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sifuna D, Kaime J: The effect of in-service education and training (INSET) programmes in mathematics and science on classroom interaction: a case study of primary and secondary schools in Kenya. Africa Education Review. 2007;4(1):104–126. 10.1080/18146620701412191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Musau LM, Migosi JA: Effect of class size on girls’ academic performance in Science, Mathematics and Technology subjects. International Journal of Education Economics and Development. 2013;4(3):278–288. 10.1504/IJEED.2013.056013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beaton AE: Mathematics Achievement in the Middle School Years. IEA’s Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). ERIC.1996. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 68. Osborne J, Simon S, Collins S: Attitudes towards science: a review of the literature and its implications. Int J Sci Educ. 2003;25(9):1049–1079. 10.1080/0950069032000032199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shrigley RL: Attitude and behavior are correlates. J Res Sci Teach. 1990;27(2):97–113. 10.1002/tea.3660270203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Simpson RD, Oliver JS: Attitude toward science and achievement motivation profiles of male and female science students in grades six through ten. Sci Educ. 1985;69(4):511–525. 10.1002/sce.3730690407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Belmont Report: The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Department of Health, Education and Welfare: Wachington, DC:OPRR Reports.1979. Reference Source [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Christensen P: The health-promoting family: a conceptual framework for future research. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(2):377–87. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marsh V, Mutemi W, Some ES, et al. : Evaluating the community education programme of an insecticide-treated bed net trial on the Kenyan coast. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(3):280–291. 10.1093/heapol/11.3.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mwanga JR, Jensen BB, Magnussen P, et al. : School children as health change agents in Magu, Tanzania: a feasibility study. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(1):16–23. 10.1093/heapro/dam037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Onyango-Ouma W, Aagaard-Hansen J, Jensen BB: The potential of schoolchildren as health change agents in rural western Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1711–22. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ayi I, Nonaka D, Adjovu JK, et al. : School-based participatory health education for malaria control in Ghana: engaging children as health messengers. Malar J. 2010;9:98. 10.1186/1475-2875-9-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gaventa J, Corrnwall A: Power and Knowledge.In Handbook of Action Research, P. Reason and H. Bradbury, Editors. SAGE Publications: London.2006;71–82. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 78. Park P: Knowledge and Participatory Research. In Handbook of Action Research, P. Reason and H. Bradbury, Editors. SAGE Publications: London.2006;83–93. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 79. Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D: Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854–857. 10.1136/jech.2004.028662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Davies A, Jones C: WT 10602/Z/12/Z. Engaging Kenyan Schools in Research: Novel Approaches using new Techniques.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Government of Kenya: Kenya Vision 2030.Ministry of Planning and National Development.2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ogembo JO, Ayot HO, Twoli NW: Predictors of extent of integration of computers in classroom teaching and learning among science and mathematics teachers in public secondary schools in Kwale County, Kenya.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 83. Government of Kenya: National Education Sector Plan Volume One: Basic Education Programme Rationale and Approach 2013-2014 - 2017-2018. M.o.E.S.a. Technology, Editor. Nairobi, Kenya.2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 84. NCoB: Children and clinical research: ethical issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 85. Holliman R, Davies G: Moving beyond the seductive siren of reach: planning for the social and economic impacts emerging from school-university engagement with research. Journal of Science Communication. 2015;14(03):1–10. 10.22323/2.14030306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hyder AA, Krubiner CB, Bloom G, et al. : Exploring the ethics of long-term research engagement with communities in low-and middle-income countries. Public Health Ethics. 2012;5(3):252–262. 10.1093/phe/phs012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Abubakar A, Kariuki SM, Tumaini JD, et al. : Community perceptions of developmental and behavioral problems experienced by children living with epilepsy on the Kenyan coast: A qualitative study. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:74–78. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Brooker S, Okello G, Njagi K, et al. : Improving educational achievement and anaemia of school children: design of a cluster randomised trial of school-based malaria prevention and enhanced literacy instruction in Kenya. Trials. 2010;11(1):93. 10.1186/1745-6215-11-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]