Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to detect the efficacy and safety of tacrolimus (TAC) in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis.

Methods

Associated studies were extracted from the PubMed and the Cochrane Library on July 10, 2018, and applicable investigations were pooled and analyzed by meta-analysis. Data on complete remission (CR), total remission (TR; complete plus partial remission), proteinuria levels, urine erythrocyte number, albumin, glomerular filtration rate, negative rate of ds-DNA, C3 levels, C4 levels, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLE-DAI), etc, were extracted and pooled using RevMan 5.3.

Results

In the therapeutic regimen of TAC + glucocorticoids (GC) vs cyclophosphamide (CYC) + GC, the results indicated that the TAC group had high values of CR, TR, albumin, and negative rate of ds-DNA, and low values of proteinuria levels and SLE-DAI when compared with those in CYC group (all P<0.05). In the therapeutic regimen comprising TAC + GC vs mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) + GC, the results indicated that the difference of CR, TR, proteinuria levels, and albumin between TAC group and MMF group were not significant (all P>0.05). In the therapeutic regimen comprising TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC, multitarget therapy group showed higher values of CR, TR, urinary protein decline, and rise of serum albumin when compared with CYC group (all P<0.05).

Conclusion

TAC is an effective and safe agent in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis.

Keywords: tacrolimus, lupus nephritis, complete remission, CR, total remission, TR, meta-analysis

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies target a variety of self-antigens,1 and persistent disease activity is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Immune activation of T-helper cells and B cells takes part in the pathogenesis, and endogenous antigens are generated.2,3 To clear the antigens, the immune system produces the autoantibodies, which induces tissue inflammation and multiorgan inflammation, especially in kidney.4,5 Lupus nephritis is one of the most serious complications of SLE and occurs in up to 60% of patients worldwide; among them, 50%–80% are pediatric-onset SLE cases.6–9 Without drug intervention, long-term inflammation may cause irreversible damage to kidney and may cause chronic kidney disease, which subsequently develops into end-stage renal disease.

Traditional therapy for SLE involved the combination of glucocorticoids (GC) with cyclophosphamide (CYC), which was found to be effective in improving long-term prognosis. However, its application was limited because of severe adverse effects, including sepsis, amenorrhea, hemorrhagic cystitis, malignancy, and so on. New immunosuppressants such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclosporine, and tacrolimus (TAC) are needed to reverse the situation. Also, azathioprine (AZA) or MMF is used for maintenance therapy because of their safety and function of inducing remission of kidney function.4,10 Though various immunosuppressive drugs play a role in the battle with SLE, few randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted to make comparisons among the available treatments for lupus nephritis or interpret the efficacy and safety of TAC.11

TAC has a long history in kidney transplantation. As a calcineurin inhibitor, it hinders T-cell activation by inhibiting the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin and combining with FKBP12.5,12 It also results in the decrease of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, and TNF-α.9,13 In the past years, some clinical trials were conducted to explore whether the use of TAC can lead to a better remission of lupus nephritis.

The update of immunosuppressive drugs helps not only in increasing the long-term survival rate of the patients but also in decreasing the associated side effects of corticosteroids.12,14 Thus, we performed a systematic review and meta-analyses to assess the efficacy and safety of TAC in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Systematic searches were performed in the Cochrane Library and PubMed without language limitations from when the database is created to July 10, 2018 using the search terms: (tacrolimus OR FK506 OR TAC) AND (systemic lupus erythematosus OR systemic lupus erythematous OR lupus nephritis OR lupus glomerulonephritis OR lupus nephropathy). We also checked the references cited in the recruited articles for additional reports.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) study type: randomized controlled trials, open-label prospective studies, case-control studies, observational studies, and cohort studies; 2) object of the study: all patients regardless of race who met the diagnostic criteria only for lupus nephritis; 3) interventions: TAC for treatment; and 4) baseline information: TAC was compared with placebo or other drugs.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for the study were as follows: 1) case reports, reviews, letters, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis; 2) studies that did not include different therapeutic regimens; and 3) the diagnostic criteria were not clear.

Outcome measures

Efficacy of TAC: complete remission (CR), total remission (TR; total CR plus partial remission [PR]), proteinuria levels, urine erythrocyte number, albumin, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), negative rate of ds-DNA, C3 levels, C4 levels, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLE-DAI), urinary protein decline, and rise of serum albumin.

Safety of TAC: gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, infection, pneumonia, upper respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, herpes zoster or varicella, alopecia, irregular menstruation, increase in blood creatinine levels, and liver function disorder.

Data collection

According to the predetermined inclusion criteria, two reviewers scanned the titles and abstracts of the included studies or read the full text to screen for possible relevant literature. Discordant opinions were discussed and resolved by other reviewers. Only randomized controlled trials, randomized cross-over studies, and prospective studies that were related to TAC treatment were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data were extracted from the included literature and Review Manager version 5.3 software was used to pool the results. Heterogeneity was quantified using I2 statistics and explored for all the meta-analyses. On the basis of the test of heterogeneity, when the P-value ≥0.1, a fixed-effects model was used. Otherwise, the results were pooled using a random-effects model. Continuous data were expressed using weighted mean differences (WMDs), and binary data were expressed using the OR. 95% CIs were calculated for the included studies with the Mantel–Haenszel (M–H) method. A P-value <0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

Results

Search results

In this meta-analysis, 13 clinical trials15–27 were related to TAC for lupus nephritis (Table 1). There were 12 randomized controlled studies and one21 prospective study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

| Author, year | Study design | Treatment strategies | Detailed scheme | Patient characteristics | Main outcome measures | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Zhang et al, 200625 | Randomized clinical trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received oral prednisone (0.6 mg/kg per day, maximal dose was 40 mg/d) divided into three times for 4 weeks. The daily dose of prednisone was tapered by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to 20 mg/d and then by 2.5 mg/d every 2 weeks to maintenance dose of 10 mg/d. Some patients with renal active lesion received intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.5 g/d for 3 d). The TAC + GC group received TAC (0.1 mg/kg per day, twice daily) and blood concentration of TAC maintained within 5–15 ng/mL. The initial dose is treated for at least 3 months. If the patient achieves complete remission, the TAC is reduced to 0.08 mg/kg per day, twice daily, and blood concentration of TAC is maintained within 5–10 ng/mL. For patients in the CYC + GC group, IVCY was initiated at a dose of 0.75 g/m2 body surface area and then adjusted to a dose of 0.5–1.0 g/m2 body surface area every 4 weeks for six doses. | The average age of 34 female patients was 27.1±9.9 years, and the patients had a diagnosis of class IV LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, urine erythrocyte number, albumin, negative rate of ds-DNA, SLE-DAI | Gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hyperglycemia, infection, pneumonia, herpes zoster or varicella, alopecia, irregular menstruation, blood creatinine increase, liver function disorder |

| Zhang et al, 200624 | Randomized clinical trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received oral prednisone (0.6 mg/kg per day, maximal dose was 40 mg/d) divided into three times for 4 weeks. The daily dose of prednisone was tapered by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to 20 mg/d and then by 2.5 mg/d every 2 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d. Some patients with renal active lesion received intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.5 g/d for 3 d). The TAC + GC group received TAC (0.1 mg/kg per day, twice daily) and blood concentration of TAC maintained within 5–15 ng/mL. The initial dose is treated for at least 3 months. If the patient achieves complete remission, the TAC is reduced to 0.08 mg/kg per day, twice daily, and blood concentration of TAC is maintained within 5–10 ng/mL. For patients in the CYC + GC group, IVCY was initiated at a dose of 0.75 g/m2 body surface area and then adjusted to a dose of 0.5–1.0 g/m2 body surface area every 4 weeks for six doses. | The average age of 37 female patients was 30.0±9.8 years, and the patients had a diagnosis of class V + IV LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, urine erythrocyte number, albumin, C3 levels, C4 levels, negative rate of ds-DNA, SLE-DAI | Gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, infection, upper respiratory infection, herpes zoster or varicella, urinary tract infection, alopecia, irregular menstruation, blood creatinine increase, liver function disorder |

| Xu et al, 200722 | Randomized clinical trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) for 8 weeks. The daily dose of prednisone was tapered by 5 mg/d every 1–2 weeks to 30 mg/d and then by 2.5 mg/d every 1–2 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d. The TAC + GC group received TAC (0.1 mg/kg per day, twice daily) and blood concentration of TAC maintained within 5–15 ng/mL. The initial dose is treated for at least 6 months. For patients in the CYC + GC group, IVCY was initiated at a dose of 1 g per month for six times, and then adjusted to once every 3 months. The total treatment was for 2 years. | 40 patients had a diagnosis of class III, IV, V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, albumin, C3 levels, C4 levels, negative rate of ds-DNA, SLE-DAI | Leucopenia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, infection, blood creatinine increase |

| Hong et al, 200717 | Randomized clinical trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients were randomly assigned to either oral TAC (initial dose 0.1 mg/kg/d) in addition to corticosteroids (initial dose 0.8 mg/kg/d) or intravenous cyclophosphamide (0.5–0.75 g/m2 monthly) in addition to corticosteroids (initial dose 0.8 mg/kg/d). | Twenty-five patients (23 females, 2 males; 30.7±5.1 years old) with diffuse proliferative LN proven by renal biopsy were included. | CR, TR | NA |

| Chen et al 201116 | Multicenter noninferiority randomized controlled trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d). The daily dose of prednisone was tapered by 10 mg/d every 2 weeks to 40 mg/d and then by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d. The TAC + GC group received TAC (0.05 mg/kg/d, twice daily) and blood concentration of TAC was maintained within 5–10 ng/mL. For patients in the CYC + GC group, IVCY was initiated at a dose of 750 mg/m2 of body surface area for 6 months. | Eligibility criteria for this trial included age 14–65 years, and the patients had a diagnosis of class III, IV, V, III + V, IV + V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, GFR | Gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hyperglycemia, infection, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, herpes zoster or varicella, urinary tract infection, alopecia, irregular menstruation, blood creatinine increase, liver function disorder |

| Wang et al, 201221 | A non-randomized prospective cohort study | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received oral prednisone (0.8 mg/kg/d, maximum dose 50 mg/d) for 4 weeks, and this dose was gradually decreased to 0.5 mg/kg/d at 1 month and maintained for 2 weeks after PR. The prednisone dose was then tapered over 4 weeks by 5 mg per week, until CR, and then maintained at 10–15 mg/d during the maintenance period. No patients in the two groups were given intravenous pulse methylprednisolone. For the TAC + GC group, the initial dosage of TAC was 0.08/mg/kg/d for patients with GFR more than 40 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 0.04 mg/kg/d for patients with GFR less than 40 mL/min/1.73 m2. The dosage was adjusted to achieve a whole blood TAC concentration of 6–8 ng/mL when induction therapy was required, 4–6 ng/mL when maintenance therapy was required, and 4.0 ng/mL when serum creatinine was more than 133 mmol/L and GFR was less than 40 mL/min/1.73 m2. For the CYC group, the protocol was pulse CYC at a dose of 750 mg/m2 every month for 6 months followed by AZA (100 mg/d) for 6 months. | 40 patients (32 female, eight male; median age at study entry, 33.88±9.72 (range 16–64) years) with SLE entered this open, prospective study of LN, and had a diagnosis of class IV, V, III + V, IV + V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, GFR, C3 levels, C4 levels, negative rate of ds-DNA, SLE-DAI | Gastrointestinal syndrome, hypertension, hyperglycemia, pneumonia, herpes zoster or varicella, urinary tract infection, irregular menstruation, liver function disorder |

| Li et al, 201218 | Randomized, open-label, clinical trial | TAC + GC vs CYC + GC vs MMF + GC | The patients were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment groups (MMF + GC group, TAC + GC group, or CYC + GC group) in an open-label manner. The daily doses of prednisolone were started at 0.8–1.0 mg/kg/d orally in a maximum dose of 60 mg/d, reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until the dose was 40 mg/d, after which it was reduced by 5 mg every 2 weeks, until a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d had been reached, at ~4 months. Pulse intravenous corticosteroids were prohibited throughout the study. The initial dose of TAC was 0.08–0.1 mg/kg/d administered orally in two divided doses and was titrated to maintain 12-hour trough levels at 6–8 ng/mL. Oral MMF was given twice daily, at a dose of 1.5 g/d in patients weighing 55 kg and 2.0 g/d in whose body weight >55 kg. IVC was given in monthly pulses of 0.5–0.75 g/m2 of body surface. Immunosuppressive agents (MMF, TAC, and CYC) were prescribed during 6 months. | Patients aged from 18 to 65 years, and had a diagnosis of class III, IV, V, III + V, IV + V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, negative rate of ds-DNA | Leucopenia, hyperglycemia, infection, irregular menstruation, blood creatinine increase, liver function disorder |

| Yap et al, 201223 | A prospective, randomized, open-label study | TAC + GC vs MMF + GC | In both groups, prednisolone was commenced at 0.8 mg/kg/d (maximum 50 mg/d), then tapered by 5 mg/d every fortnight until reaching a dose of 10 mg/d after about 4 months. Prednisolone dosage was further reduced to 7.5 mg/d after 4 weeks and then maintained at this dose until the end of 12 months. Prednisolone dose in the second year was 7.5 mg/d in patients with a body weight of 50 kg or higher and 5 mg/d in other subjects. TAC was commenced at 0.1–0.15 mg/kg per day in two divided doses, followed by titration to achieve the target 12-hour trough blood level of 6–8 mg/L for the first 6 months, 5.0–5.9 mg/L for the subsequent 6 months, and 3.0–4.9 mg/L during the second year. MMF dose was 0.75–1 g bid for the first 6 months, then 0.75 g bid until the end of 12 months, and 0.5 g bid during the second year. | 16 male or female patients 18–65 years of age, biopsy-proven class V membranous LN without significant endocapillary proliferation within 6 months, according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, albumin | Leucopenia, hyperglycemia, infection, herpes zoster or varicella |

| Mok et al 201620 | An open randomized controlled parallel group study | TAC + GC vs MMF + GC | All patients were given oral prednisone (0.6 mg/kg/d for 6 weeks, then tapered by 5 mg/d every week to <10 mg/d), which was continued indefinitely as maintenance therapy. Participants were randomized by computer-generated blocks of four in a 1:1 ratio to one of the following treatment arms: (1) TAC for 6 months (Initial dosage 0.1 mg/kg/d in two divided doses, reduced to 0.06 mg/kg/d if clinical response was satisfactory at month 3) or (2) MMF (2 g/d initially, augmented to up to 3 g/d if clinical response was suboptimal at month 3), in two divided doses for 6 months. | 150 male or female patients (92% women; aged 35.5±12.8 years) were divided into two groups, and biopsy-proven class V, III + V, IV + V according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, proteinuria levels, albumin | Hyperglycemia, serious infection, herpes zoster or varicella, blood creatinine increase |

| Bao et al 200815 | Multicenter, randomized, open-label, clinical trial | TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC | All patients in the two groups received intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.5 g/d for 3 days) at the beginning, following by oral prednisone (0.6–0.8 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks and then reduced by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to 20 mg/d; after that point, it was reduced by 2.5 mg/d every 2 weeks until a maintenance dosage of 10 mg/d). In TAC + MMF + GC group, a triple therapy of MMF, TAC, and corticosteroid was adopted. The TAC dosage was initiated at 4 mg/d (3 mg/d for ≤50 kg) twice daily, and blood concentration of TAC was maintained within 5–7 ng/mL. The dosage of MMF was initiated at 1.0 g/d (0.75 g/d for ≤50 kg) twice daily. Mycophenolic acid concentrations were measured and the dosage was titrated to maintain an area under the time concentration curve from 0 to 12 hours of mycophenolic acid at 20–45 mg⋅h/L. In the CYC + GC group, CYC pulse therapy was applied monthly. Dosing was initiated at 0.75 g/m2 of body surface area for the first month and then adjusted between 0.5 and 1.0 g/m2 body surface area monthly according to the white cell count after the infusion. | Eligible patients were of either gender and between 12 and 60 years of age, and had a diagnosis of class V + IV LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, urinary protein decline, rise of serum albumin, negative rate of ds-DNA | Gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, herpes zoster or varicella, urinary tract infection, alopecia, irregular menstruation |

| Liu et al, 201519 | Multicenter, randomized, open-label, clinical trial | TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC | Patients in both groups received intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (0.5 g/d) for 3 days, followed by oral prednisone (0.6 mg/kg/day) every morning for 4 weeks. The daily dose of prednisone was tapered by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to 20 mg/d and then by 2.5 mg/d every 2 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d. After methylprednisolone pulse therapy, the multitarget group received MMF (0.5 g twice daily) and TAC (2 mg twice daily). For patients in the IVCY group, after completion of methylprednisolone pulse therapy, IVCY was initiated at a dose of 0.75 g/m2 body surface area and then adjusted to a dose of 0.5–1.0 g/m2 body surface area every 4 weeks for six doses. | Patients aged 18–65 years with biopsy-proven LN diagnosed within 6 months before enrollment, and had a diagnosis of class III, IV, V, III + V, and IV + V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, TR, urinary protein decline, rise of serum albumin, negative rate of ds-DNA | Gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, herpes zoster or varicella, urinary tract infection, alopecia, irregular menstruation |

| Sakai et al, 201827 | A prospective, single-arm, single-center, open-label pilot study | TAC + CYC + GC vs CYC + GC | Oral prednisolone was started at a dose of 0.6–1.0 mg/kg/d. CYC was administered intravenously at a dose of 500 mg every 2 weeks for a total of six times as per the Euro-Lupus protocol. TAC was administered orally at a dose of up to 3.0 mg/d as per national health insurance guidelines in Japan. After 2 weeks, prednisolone was tapered by 5 mg/d every 2 weeks to 20 mg/d, after which it was usually reduced by 2.5 mg/d every 2–4 weeks to a maintenance dosage of 510 mg/d, at the discretion of an attending physician. TAC was continued as maintenance therapy after induction therapy achieved remission. | 15 patients aged 18–64 years with active LN were included, and had a diagnosis of class IV, III + V, and IV + V LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | CR, albumin, C3 levels, C4 levels, negative rate of ds-DNA, SLE-DAI, etc | Death due to thrombotic microangiopathy, cellulitis, pneumocystis pneumonia, anterior thoracic abscess, myelosuppression, deepvein thrombosis |

| Miyasaka et al, 200926 | A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind study | TAC + GC vs GC | Eligible patients had been on GC therapy at a daily dose of more than 10 mg for at least 8 weeks prior to administration of the study drug, and the attending physician had judged that it was difficult to reduce the dose to below 10 mg/d because of the possibility of recurrence. Sixty-three patients were assigned randomly to the TAC group or the placebo group and were treated with oral TAC (3 mg/d) or placebo once daily after dinner for 28 weeks. After starting the trial, the GC dose could not be increased, although tapering was allowed. | 63 patients were included, and had a diagnosis of class II, III, IV, V, VI, II + III LN according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of LN. | Daily urinary protein excretion, urinary red blood cell count, ds-DNA, C3 levels, maintenance of normal serum creatinine, etc | Gastrointestinal syndrome, hypertension, hyperglycemia, etc |

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; CYC, cyclophosphamide; IVC, intravenous cyclophosphamide; IVCY, intravenous cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; AZA, azathioprine; CR, complete remission; TR, total remission (complete plus partial remission [PR]); GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SLE-DAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index; LN, lupus nephritis; NA, not available; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; RPS, Renal Pathology Society; bid, twice a day.

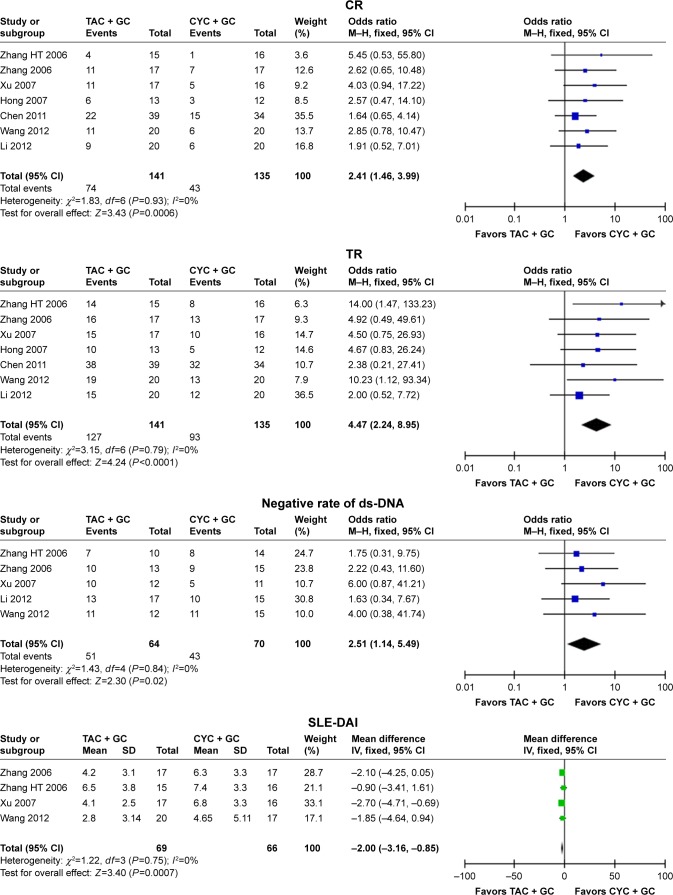

Study of the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs CYC + GC

Seven studies16–18,21,22,24,25 were included into the meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of TAC in patients with lupus nephritis. In the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs CYC + GC, the results indicated that TAC + GC group had high values of CR (OR =2.41, 95% CI: 1.46–3.99, P=0.0006; Figure 1 and Table 2), TR (OR =4.47, 95% CI: 2.24–8.95, P<0.0001; Figure 1 and Table 2), albumin (WMD =0.38, 95% CI: 0.10–0.66, P=0.009; Table 2), negative rate of ds-DNA (OR =2.51, 95% CI: 1.14–5.49, P=0.02; Figure 1 and Table 2), and low values of proteinuria levels (WMD =−0.68, 95% CI: −1.21 to −0.15, P=0.01; Table 2) and SLE-DAI (OR =−2.00, 95% CI: −3.1 to −0.85, P=0.0007; Figure 1 and Table 2) when compared with those in CYC group. However, the differences in urine erythrocyte number, GFR, C3 levels, and C4 levels were not significant between TAC + GC group and CYC + GC group (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Assessment of the efficacy of tacrolimus in patients with lupus nephritis (TAC + GC vs CYC + GC).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; CYC, cyclophosphamide; CR, complete remission; TR, total remission (complete plus partial remission); SLE-DAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the efficacy of tacrolimus in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis

| Therapeutic regimen | Indicators | Number of studies | Q test, P-value | Model selected | OR/WMD (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | CR | 7 | 0.93 | Fixed | 2.41 (1.46, 3.99) | 0.0006 |

| TR | 7 | 0.79 | Fixed | 4.47 (2.24, 8.95) | <0.0001 | |

| Proteinuria levels | 4 | 0.41 | Fixed | −0.68 (−1.21, −0.15) | 0.01 | |

| Urine erythrocyte number | 2 | 0.93 | Fixed | −16.96 (−55.00, 21.07) | 0.38 | |

| Albumin | 3 | 0.13 | Fixed | 0.38 (0.10, 0.66) | 0.009 | |

| GFR | 2 | 0.51 | Fixed | −0.77 (−1.66, 0.12) | 0.09 | |

| Negative rate of ds-DNA | 5 | 0.84 | Fixed | 2.51 (1.14, 5.49) | 0.02 | |

| C3 levels | 3 | 0.41 | Fixed | 0.07 (−0.08, 0.21) | 0.37 | |

| C4 levels | 3 | 0.41 | Fixed | 0.02 (−0.04, 0.08) | 0.52 | |

| SLE-DAI | 4 | 0.75 | Fixed | −2.00 (−3.16, −0.85) | 0.0007 | |

| TAC + GC vs MMF + GC | CR | 3 | 0.18 | Fixed | 0.95 (0.54, 1.64) | 0.84 |

| TR | 3 | 0.42 | Fixed | 1.43 (0.70, 2.91) | 0.33 | |

| Proteinuria levels | 2 | 0.09 | Random | 0.08 (−0.39, 0.55) | 0.75 | |

| Albumin | 2 | 0.02 | Random | −0.90 (−5.77, 3.96) | 0.72 | |

| TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC | CR | 2 | 0.07 | Random | 5.13 (0.75, 35.02) | 0.10 |

| TR | 2 | 0.15 | Fixed | 3.32 (2.08, 5.32) | <0.00001 | |

| Urinary protein decline | 2 | 0.12 | Fixed | −0.90 (−1.40, −0.40) | 0.0004 | |

| Rise of serum albumin | 2 | 0.25 | Fixed | 1.96 (0.63, 3.29) | 0.004 | |

| Negative rate of ds-DNA | 2 | 0.82 | Fixed | 1.67 (1.00, 2.79) | 0.05 | |

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; CYC, cyclophosphamide; CR, complete remission; TR, total remission, complete plus partial remission; SLE-DAI, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; WMD, weighted mean difference.

The safety of TAC was also assessed in patients with lupus nephritis. In this meta-analysis, the incidence rates of gastrointestinal syndrome (OR =0.30, 95% CI: 0.12–0.78, P=0.01; Table 3), leucopenia (OR =0.25, 95% CI: 0.08–0.74, P=0.01; Table 3), and irregular menstruation (OR =0.16, 95% CI: 0.05–0.45, P=0.0006; Table 3) in TAC + GC group were lower than those in CYC + GC group. The incidence rates of infection, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, alopecia, and liver function disorder in TAC + GC group were lower than those in CYC + GC group, although there were no statistical differences between the groups (Table 3). However, the incidence rates of hypertension, hyperglycemia, herpes zoster or varicella, and increase in blood creatinine levels in TAC + GC group were higher than those in CYC + GC group, although there were no statistical differences between the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the safety of tacrolimus in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis

| Therapeutic regimen | Indicators | Number of studies | Q test, P-value | Model selected | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TAC + GC vs CYC + GC | Gastrointestinal syndrome | 4 | 0.63 | Fixed | 0.30 (0.12, 0.78) | 0.01 |

| Leucopenia | 5 | 0.71 | Fixed | 0.25 (0.08, 0.74) | 0.01 | |

| Hypertension | 3 | 0.93 | Fixed | 1.57 (0.41, 5.91) | 0.51 | |

| Hyperglycemia | 6 | 0.64 | Fixed | 1.66 (0.78, 3.54) | 0.19 | |

| Infection | 5 | 0.23 | Fixed | 0.77 (0.42, 1.43) | 0.41 | |

| Upper respiratory infection | 2 | 0.45 | Fixed | 0.90 (0.90, 4.18) | 0.89 | |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 0.53 | Fixed | 0.42 (0.09, 1.93) | 0.26 | |

| Herpes zoster or varicella | 4 | 0.54 | Fixed | 1.21 (0.45, 3.21) | 0.71 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 | 0.69 | Fixed | 0.72 (0.25, 2.05) | 0.53 | |

| Alopecia | 3 | 0.33 | Fixed | 0.59 (0.19, 1.83) | 0.36 | |

| Irregular menstruation | 5 | 0.90 | Fixed | 0.16 (0.05, 0.45) | 0.0006 | |

| Blood creatinine increase | 5 | 0.75 | Fixed | 1.52 (0.50, 4.60) | 0.46 | |

| Liver function disorder | 4 | 0.98 | Fixed | 0.52 (0.23, 1.20) | 0.13 | |

| TAC + GC vs MMF + GC | Leucopenia | 2 | 0.51 | Fixed | 0.52 (0.06, 4.12) | 0.53 |

| Hyperglycemia | 3 | 0.88 | Fixed | 2.25 (0.69, 7.33) | 0.18 | |

| Infection | 2 | 0.05 | Random | 0.95 (0.06, 16.03) | 0.97 | |

| Serious infection | 2 | 0.48 | Fixed | 0.43 (0.15, 1.18) | 0.10 | |

| Herpes zoster or varicella | 2 | 0.74 | Fixed | 0.13 (0.03, 0.53) | 0.004 | |

| Blood creatinine increase | 2 | 0.33 | Fixed | 13.54 (1.75, 104.81) | 0.01 | |

| TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC | Gastrointestinal syndrome | 2 | 0.78 | Fixed | 0.16 (0.08, 0.35) | <0.00001 |

| Leucopenia | 2 | 0.20 | Fixed | 0.16 (0.04, 0.59) | 0.006 | |

| Hypertension | 2 | 0.48 | Fixed | 3.15 (1.06, 9.29) | 0.04 | |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 | 0.61 | Fixed | 1.46 (0.43, 4.93) | 0.54 | |

| Upper respiratory infection | 2 | 0.18 | Fixed | 0.91 (0.51, 1.65) | 0.76 | |

| Pneumonia | 2 | 0.60 | Fixed | 2.06 (0.76, 5.61) | 0.16 | |

| Herpes zoster or varicella | 2 | 0.64 | Fixed | 1.92 (0.75, 4.91) | 0.18 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 0.75 | Fixed | 0.66 (0.18, 2.38) | 0.52 | |

| Alopecia | 2 | 0.38 | Fixed | 0.52 (0.20, 1.33) | 0.17 | |

| Irregular menstruation | 2 | 0.85 | Fixed | 0.25 (0.07, 0.93) | 0.04 | |

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; CYC, cyclophosphamide.

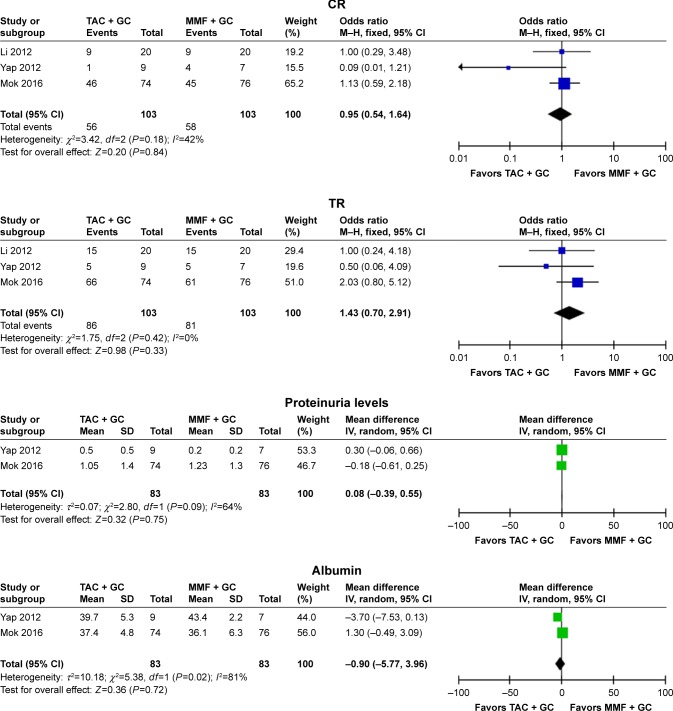

Study of the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs MMF + GC

Three studies18,20,23 were included into the meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of TAC in patients with lupus nephritis with the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs MMF + GC, and the results indicated that the differences in CR, TR, proteinuria levels, and albumin levels between TAC + GC group and MMF + GC group were not statistically significant (CR: OR =0.95, 95% CI: 0.54–1.64, P=0.84; TR: OR =1.43, 95% CI: 0.70–2.91, P=0.33; proteinuria levels: WMD =0.08, 95% CI: −0.39 to 0.55, P=0.75; albumin: WMD =−0.90, 95% CI: −5.77 to 3.96, P=0.72; Figure 2 and Table 2).

Figure 2.

Assessment of the efficacy of tacrolimus in patients with lupus nephritis (TAC + GC vs MMF + GC).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; GC, glucocorticoids; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; CR, complete remission; TR, total remission, complete plus partial remission; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

The safety of TAC was also assessed in patients with lupus nephritis. In this meta-analysis, the incidence rate of herpes zoster or varicella in TAC + GC group was lower than that in MMF + GC group (OR =0.13, 95% CI: 0.03–0.53, P=0.004; Table 3). However, the incidence rate of blood creatinine increase in TAC + GC group was higher than that in MMF + GC group (OR =0.13, 95% CI: 0.03–0.53, P=0.004; Table 3). The incidence rates of leucopenia, infection, and serious infection in TAC + GC group were lower than those in MMF + GC group, although there were no statistical differences (Table 3). However, the incidence rate of hyperglycemia in TAC + GC group was higher than that in MMF + GC group, although there was no statistically significant difference (Table 3).

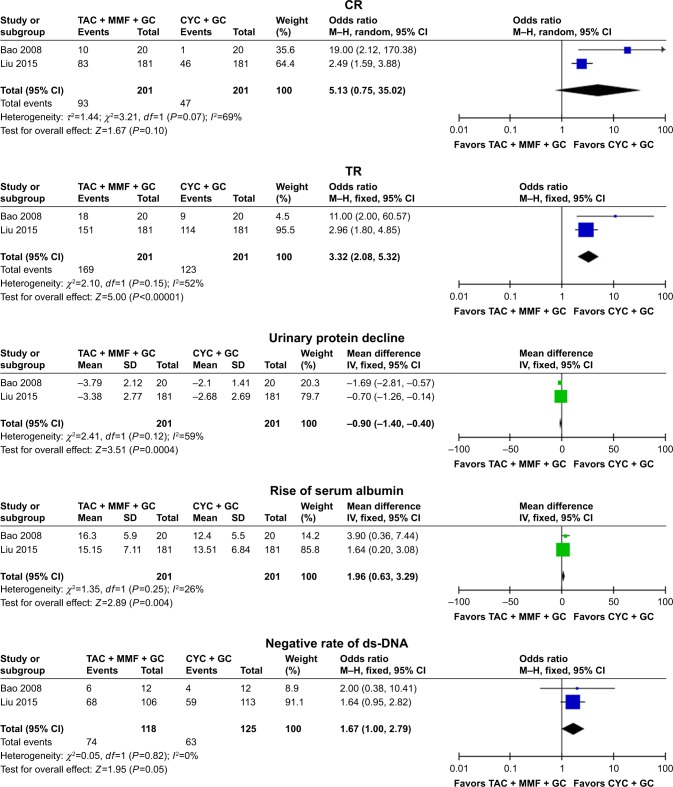

Study of the therapeutic regimen of TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC

Two studies15,19 were included into the meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of TAC in patients with lupus nephritis with the therapeutic regimen of TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC, the results indicated that the differences of TR, urinary protein decline, and rise of serum albumin between TAC + GC group and MMF + GC group were notable (TR: OR =3.32, 95% CI: 2.08–5.32, P<0.00001; urinary protein decline: WMD =−0.90, 95% CI: −1.40 to −0.40, P=0.0004; rise of serum albumin: WMD =1.96, 95% CI: 0.63–3.29, P=0.004; Figure 3 and Table 2). The TAC + MMF + GC group showed high CR rate (OR =5.13, 95% CI: 0.75–35.02, P=0.10) and negative rate of ds-DNA (OR =1.67, 95% CI: 1.00–2.79, P=0.05), although there were no statistical differences (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3.

Assessment of the efficacy of tacrolimus in patients with lupus nephritis (TAC + MMF + GC vs CYC + GC).

Abbreviations: TAC, tacrolimus; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; GC, glucocorticoids; CYC, cyclophosphamide; CR, complete remission; TR, total remission, complete plus partial remission; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

The safety of TAC was also assessed in patients with lupus nephritis. In this meta-analysis, the incidence rates of gastrointestinal syndrome (OR =0.16, 95% CI: 0.08–0.35, P<0.00001; Table 3), leucopenia (OR =0.16, 95% CI: 0.04–0.59, P=0.006; Table 3), and irregular menstruation (OR =0.25, 95% CI: 0.07–0.93, P=0.04; Table 3) in TAC + MMF + GC group were lower than those in CYC + GC group. In this meta-analysis, the incidence rate of hypertension (OR =3.15, 95% CI: 1.06–9.29, P=0.04; Table 3) in TAC + MMF + GC group was higher than that in CYC + GC group. The incidence rates of upper respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, and alopecia in TAC + MMF + GC group were lower than those in CYC + GC group, although there were no statistical differences (Table 3). However, the incidence rates of hyperglycemia, pneumonia, and herpes zoster or varicella in TAC + MMF + GC group were higher than those in CYC + GC group, although there were no statistical differences (Table 3).

Discussion

In the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs CYC + GC, the results indicated that TAC + GC group had high values of CR, TR, albumin, and negative rate of ds-DNA, and low values of proteinuria levels and SLE-DAI when compared with those in CYC + GC group. In this meta-analysis for adverse events, the TAC + GC treatment showed lower incidence rates of gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, and irregular menstruation than the CYC + GC treatment. The TAC + GC treatment also showed lower incidence rates of infection, upper respiratory infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, alopecia, and liver function disorder when compared with the CYC + GC treatment. However, the TAC + GC treatment showed higher incidence rates of hypertension, hyperglycemia, herpes zoster or varicella, and blood creatinine level increase when compared with the CYC + GC treatment. In a previous study, Chen et al28 included six studies into the meta-analysis and reported that TAC was superior to CYC in terms of CR rate, TR rate, and anti-dsDNA negative conversion rate. TAC was also associated with less adverse events of gastrointestinal syndrome and amenorrhea than CYC. Kraaij et al29 included five RCTs to investigate TAC in combination with steroids, and reported that TAC-based induction treatment led to a significantly higher total renal response. Our meta-analysis included more studies and assessed more indicators than the previous meta-analyses.

In the therapeutic regimen of TAC + GC vs MMF + GC of our meta-analysis, the results indicated that the differences in CR, TR, proteinuria levels, and albumin between TAC + GC group and MMF + GC group were not statistically different. The incidence rate of herpes zoster or varicella in TAC + GC group was lower than that in MMF + GC group. However, the incidence rate of blood creatinine increase in TAC + GC group was higher than that in MMF + GC group. In a previous study, Chen et al28 included six studies into the meta-analysis and reported that, in the induction therapy of LN, TAC and MMF were more effective and safer when compared with CYC, but there were no differences of efficacy (CR, TR, proteinuria levels) or safety (major infection, serious infection) between the two treatments. Our meta-analysis included more studies and assessed more indicators than the previous meta-analyses.

We also assessed the multitarget therapy (including the TAC) for induction treatment of lupus nephritis, and reported that the differences in TR, urinary protein decline, and rise of serum albumin between TAC + GC group and MMF + GC group were notable. The TAC + MMF + GC group shows high CR rate and negative rate of ds-DNA. Calcineurin inhibitors, including TAC and cyclosporine A, inhibit T-cell proliferation by binding to cyclophilin and inhibiting calcineurin phosphatase activity, thus blocking the activation of T-cell-specific transcription factors.30,31 MMF, when hydrolyzed to the active drug mycophenolic acid, is a potent inhibitor of the proliferation of T and B lymphocytes via reversible inhibition of inosine 5-monophosphate dehydrogenase.30 CYC can selectively deplete the regulatory T cells and enhance the effector T-cell function.32 We speculated that multitarget therapy can well inhibit the proliferation of T and/or B lymphocytes and can obtain good efficacy. The drug doses used in multitarget therapy is much lower than that used for single target therapy, and the adverse reactions may be reduced. In this meta-analysis, the incidence rates of gastrointestinal syndrome, leucopenia, and irregular menstruation in TAC + MMF + GC group were lower than that in CYC + GC group. The incidence rates of upper respiratory infection, urinary tract infection, and alopecia in TAC + MMF + GC group was lower than those in CYC + GC group. There was no other meta-analysis that assessed this relationship.

In this systematic review, we also included two studies assessing the efficacy and safety of TAC in induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis. Miyasaka et al26 conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of TAC for the treatment of lupus nephritis, and reported that the lupus nephritis disease activity index was decreased in the TAC group and increased in the placebo group. Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 80.0% of the placebo group and 92.9% of the TAC group, but the difference was not significant. Sakai et al27 conducted a prospective, single-center, single-arm, open-label pilot study, and reported that multitarget therapy with TAC and CYC can be a good therapeutic option for lupus nephritis.

Conclusion

In our meta-analysis, we found that TAC is an effective and safe agent for induction therapy of patients with lupus nephritis. However, more studies are needed to confirm these findings in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Guangzhou Medical Key Discipline Construction Project, the Natural Science Foundation of the Guangdong Province (no 2015A030310386), and Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Fund Project (no A2018336). All authors should be regarded as co-first authors in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.He YY, Yan Y, Zhang HF, et al. Methyl salicylate 2-O-β-d-lactoside alleviates the pathological progression of pristane-induced systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease in mice via suppression of inflammatory response and signal transduction. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:3183–3196. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S114501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cogollo E, Silva MA, Isenberg D. Profile of atacicept and its potential in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:1331–1339. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S71276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenert A, Niewold TB, Lenert P. Spotlight on blisibimod and its potential in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: evidence to date. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:747–757. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S114552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannah J, Casian A, D’Cruz D. Tacrolimus use in lupus nephritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mok CC. Calcineurin inhibitors in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017;31(3):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka H, Joh K, Imaizumi T. Treatment of pediatric-onset lupus nephritis: a proposal of optimal therapy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21(5):755–763. doi: 10.1007/s10157-017-1381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takei S, Maeno N, Shigemori M, et al. Clinical features of Japanese children and adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of 1980–1994 survey. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39(2):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1997.tb03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertsias GK, Tektonidou M, Amoura Z, et al. Joint European League against rheumatism and European renal Association-European dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of adult and paediatric lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(11):1771–1782. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogan J, Appel GB. Update on the treatment of lupus nephritis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(2):224–230. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835d921c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yap DYH, Chan TM. Lupus nephritis in Asia: clinical features and management. Kidney Dis. 2015;1(2):100–109. doi: 10.1159/000430458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh JA, Hossain A, Kotb A, Wells GA. Comparative effectiveness of immunosuppressive drugs and corticosteroids for lupus nephritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0328-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mok CC. Therapeutic monitoring of the immuno-modulating drugs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(1):35–41. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson J, Nagy S, Groth CG, Andersson U. Effects of FK506 and cyclosporin A on cytokine production studied in vitro at a single-cell level. Immunology. 1992;75(1):136–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh JA, Hossain A, Kotb A, et al. Treatments for lupus nephritis: a systematic review and network Metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(10):1801–1815. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao H, Liu ZH, Xie HL, Hu WX, Zhang HT, Li LS. Successful treatment of class V+IV lupus nephritis with multitarget therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(10):2001–2010. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen W, Tang X, Liu Q, et al. Short-term outcomes of induction therapy with tacrolimus versus cyclophosphamide for active lupus nephritis: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(2):235–244. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong R, Haijin Y, Xianglin W, Cuilan H, Nan C, Hong R. A preliminary study of tacrolimus versus cyclophosphamide in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(Suppl 6):276. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Ren H, Zhang Q, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus compared with intravenous cyclophosphamide in the induction treatment for active lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(4):1467–1472. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Zhang H, Liu Z, et al. Multitarget therapy for induction treatment of lupus nephritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):18–26. doi: 10.7326/M14-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mok CC, Ying KY, Yim CW, et al. Tacrolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil for induction therapy of lupus nephritis: a randomised controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):30–36. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, Li X, Qu L, et al. Tacrolimus versus cyclophosphamide as treatment for diffuse proliferative or membranous lupus nephritis: a non-randomized prospective cohort study. Lupus. 2012;21(9):1025–1035. doi: 10.1177/0961203312448105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu A, Lu J, Liang Y, et al. Prospective study of tacrolimus in induction trerapy of lupus nephritis. J Sun Yat-Sen Univ. 2007;28(6):683–687. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap DY, Yu X, Chen XM, et al. Pilot 24 month study to compare mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus in the treatment of membranous lupus nephritis with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrology. 2012;17(4):352–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Hu W, Xie H, et al. Tacrolimus versus intravenous cyclophosphamide in the induction therapy of diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. J Nephrol Dialy Transplant. 2006;15(6):501–506. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Hu W, Xie H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of tacrolimus versus intravenous cyclophosphamide in the induction trerapy of class V plus IV lupus nephritis. J Nephrol Dialy Transplant. 2006;15(6):508–514. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyasaka N, Kawai S, Hashimoto H. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus for lupus nephritis: a placebo-controlled double-blind multicenter study. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(6):606–615. doi: 10.1007/s10165-009-0218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakai R, Kurasawa T, Nishi E, et al. Efficacy and safety of multitarget therapy with cyclophosphamide and tacrolimus for lupus nephritis: a prospective, single-arm, single-centre, open label pilot study in Japan. Lupus. 2018;27(2):273–282. doi: 10.1177/0961203317719148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Sun J, Zou K, Yang Y, Liu G. Treatment for lupus nephritis: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(7):1089–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraaij T, Bredewold OW, Trompet S, et al. TAC-TIC use of tacrolimus-based regimens in lupus nephritis. Lupus Sci Med. 2016;3(1):e000169. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2016-000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jesus D, Rodrigues M, da Silva JAP, Inês L. Multitarget therapy of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine A for induction treatment of refractory lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2018;27(8):1358–1362. doi: 10.1177/0961203318758508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao J, Gao S, Weng Y, Zhu J, Ye H, Zhang X. Clinical efficacy of tacrolimus for treating myasthenia gravis and its influence on lymphocyte subsets. Rev Neurol. 2019;175(1–2):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2018.01.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madondo MT, Quinn M, Plebanski M. Low dose cyclophosphamide: mechanisms of T cell modulation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;42:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]