Abstract

Free radicals generate an array of DNA lesions affecting all parts of the molecule. The damage to deoxyribose receives less attention than base damage, even though the former accounts for ~20% of the total. Oxidative deoxyribose fragments (e.g., 3’-phosphoglycolate esters) are removed by the Ape1 AP endonuclease and other enzymes in mammalian cells to enable DNA repair synthesis. Oxidized abasic sites are initially incised by Ape1, thus recruiting these lesions into base excision repair (BER) pathways. Lesions such as 2-deoxypentos-4-ulose can be removed by conventional (single-nucleotide) BER, which proceeds through a covalent Schiff base intermediate with DNA polymerase β (Polβ) that is resolved by hydrolysis. In contrast, the lesion 2-deoxyribonolactone (dL) must be processed by multinucleotide (“long-patch”) BER: attempted repair via the single-nucleotide pathway leads to a dead-end, covalent complex with Polβ crosslinked to the DNA by an amide bond. We recently detected these stable DNA-protein crosslinks (DPC) between Polβ and dL in intact cells. The features of the DPC formation in vivo are exactly in keeping with the mechanistic properties seen in vitro: Polβ-DPC are formed by oxidative agents in line with their ability to form the dL lesion; they are not formed by non-oxidative agents; DPC formation absolutely requires the active-site lysine-72 that attacks the 5’-deoxyribose; and DPC formation depends on Ape1 to incise the dL lesion first. The Polβ-DPC are rapidly processed in vivo, the signal disappearing with a half-life of 15–30 min in both mouse and human cells. This removal is blocked by inhibiting the proteasome, which leads to the accumulation of ubiquitin associated with the Polβ-DPC. While other proteins (e.g., topoisomerases) also form DPC under these conditions, 60–70% of the trapped ubiquitin depends on Polβ. The mechanism of ubiquitin targeting to Polβ-DPC, the subsequent processing of the expected 5’-peptidyl-dL, and the biological consequences of unrepaired DPC are important to assess. Many other lyase enzymes that attack dL can also be trapped in DPC, so the processing mechanisms may apply quite broadly.

Keywords: Base excision DNA repair, DNA polymerase β, AP lyase, oxidative DNA damage, 2-deoxyribonolactone, DNA-protein crosslinks

Introduction

The genome is under continual threat by DNA damage from a variety of endogenous and environmental sources. The most frequent endogenous DNA lesions are chemical alterations to the nitrogenous bases that include products of oxidation, alkylation and deamination reactions (1). Many types of base damage destabilize the N-glycosylic bond, leading to the formation of abasic (AP) sites, and these add to the estimated 10,000 AP sites per day in each human cell arising from the hydrolytic loss of undamaged purine bases (2–4). Many of the hydrolytic, oxidative or alkylation base lesions cause minimal structural effects on DNA, so they escape effective processing by nucleotide excision repair (see article by Sugasawa in this issue). Instead, the mutagenic and genotoxic threat of these lesions is offset by mechanisms such as the base excision DNA repair (BER) system (5, 6) (Fig. 1).

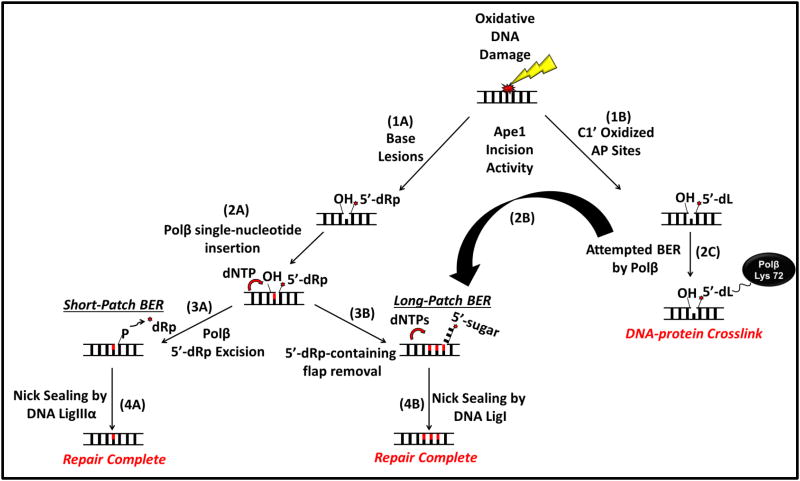

Figure 1. BER processing of oxidative DNA damage and the formation of DPC.

Following base damage and glycosylase processing, or the oxidation of DNA deoxyribose, the resulting abasic sites are cleaved by Ape1 (1A, B). The incised AP sites are then channeled through single-nucleotide (“short-patch”) or multinucleotide (“long-patch”) BER. In the former, following incision of the AP site, Polβ inserts a single-nucleotide to replace the damaged nucleotide (2A) and removes the 5’-dRp residue generated by Ape1 (3A). Synthesis of ≥2 nucleotides in multinucleotide BER generates a flap that prevents 5’-dRp excision and requires activities such as Fen1 (3B). Multinucleotide BER processes dL lesions effectively (2B), but in some circumstances attempted 5’-dL excision results in the formation of Polβ-DPC (2C). Short-patch BER is completed by DNA Ligase IIIα (4A) and in the case of long-patch BER, repair is completed by DNA Ligase I (4B) restoring the DNA backbone to its native condition.

The BER pathway can be initiated by any of the eleven DNA glycosylases in mammalian cells (7). Each glycosylase detects a specific range of base lesions and hydrolyzes the N-glycosylic bond between the base and DNA deoxyribose, forming an AP site (Fig. 1, step I). These AP sites and those generated by spontaneous purine hydrolysis are then incised by an AP endonuclease, with the main activity in mammalian cells residing in the Ape1 protein (8, 9). Ape1 hydrolyzes the phosphodiester on the immediate 5’ side of the AP site to generate a single-strand break bracketed by 3’-OH and 5’-deoxyribose-5-phosphate (5’-dRp) residues (Fig. 1, step 1A, B). In “classical” BER, only the missing nucleotide is replaced by DNA polymerase β (Polβ) (Fig. 1, step 2A), and the 5’-dRp residue is excised by a 5’-dRp lyase activity in a separate domain of Polβ (Fig.1, step 3A) (10–12). The result is a nicked DNA that is competent for ligation, usually by DNA ligase IIIα (Fig. 1, step 4A).

Another sub-pathway called long-patch BER (LP-BER) also exists, in which DNA repair synthesis replaces 2–10 nucleotides, Fen1 (“flap”) endonuclease excises the displaced strand (Fig. 1, 3B), and DNA ligase I seals the nick (13–15) (Fig. 1, step 4B). LP-BER repair synthesis can be initiated by Polβ, which may (inefficiently) insert a second nucleotide. When the 5’-dRp strand is displaced by two or more nucleotides, the 5’-dRp lyase of Polβ no longer functions, requiring Fen1 to remove the single-stranded flap. There is evidence that DNA polymerase δ and DNA polymerase ε can participate in LP-BER in a PCNA-dependent fashion, but the real contributions of the different DNA polymerases have not been established in vivo (16–19). When LP-BER was discovered (20–22), its role was unclear, with speculation about unknown modified 5’ termini possibly requiring LP-BER. A clear case came for the major oxidative lesion 2-deoxyribonolactone (dL) (Fig. 1, step 2B), which cannot be repaired by classical single-nucleotide BER (14, 23).

1. The Formation of BER-Mediated DNA-protein Crosslinks

The formation of oxidative Polβ-DPC in vitro and in vivo

Free radicals, such as the by-products of aerobic metabolism, damage all the components of DNA including the deoxyribose (24). The latter products include strand breaks with deoxyribose fragments attached to the termini, and AP sites with oxidized sugars. An important example is dL (24), which almost 50 years ago was the first chemically defined lesion of H2O2 damage (25). Other oxidative agents, such as X-rays, also form dL as one of many products (26–28), while certain agents can generate the lesion more selectively. These include some genotoxic compounds that attack C1’ of deoxyribose specifically, such as neocarzinostatin (NCS) (28–30), tirapazamine (TPZ) (31–33) and the organometallic ‘chemical nuclease’ 1,10-copper-o-phenanthroline [(Cu(OP)2] (34–37). However, the chemical instability of dL and other features prevented a systematic study of its processing for decades. Finally, three labs report generally similar methods for generating dL site-specifically in synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (38–40) which allowed a more detailed understanding of its effects in vitro (41–45). (23, 46, 47).

In vitro reactions with dL-oligonucleotide substrates showed that Ape1 cleaved the lesions about as well as it does a regular AP site (37). Subsequent BER steps were stymied, however, and molecular analysis showed that Polβ had been captured in a stable, covalent complex with the DNA (23). This study revealed a form of enzyme mechanism-based cross-linking, dependent on the lyase active-site residue lysine-72 (K72) (Fig. 1, step 2C, and Fig. 3A). In mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) extracts incubated with dL-DNA, Polβ-DPC were the major species detectable, dependent on the POLB gene (14, 48, 49). Around the same time, it was reported that E. coli endonuclease III can be trapped at (uncleaved) dL sites via that enzyme’s lyase activity (46). We later showed that mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (Polγ), which harbors a 5’-dRp lyase similar to that of Polβ, is also trapped by 5’-dL (15). In contrast to enzymatic AP lyases, the cross-linking of lysine-rich proteins such as histones to dL-DNA occurs much less efficiently, at a rate ~100-fold lower than that of Polβ (47). Thus, dL in DNA constitutes a specific threat to the various lyases that act on DNA abasic sites, especially significant because dL would be generated in vivo at a rate similar to that for 8-oxoguanine (28).

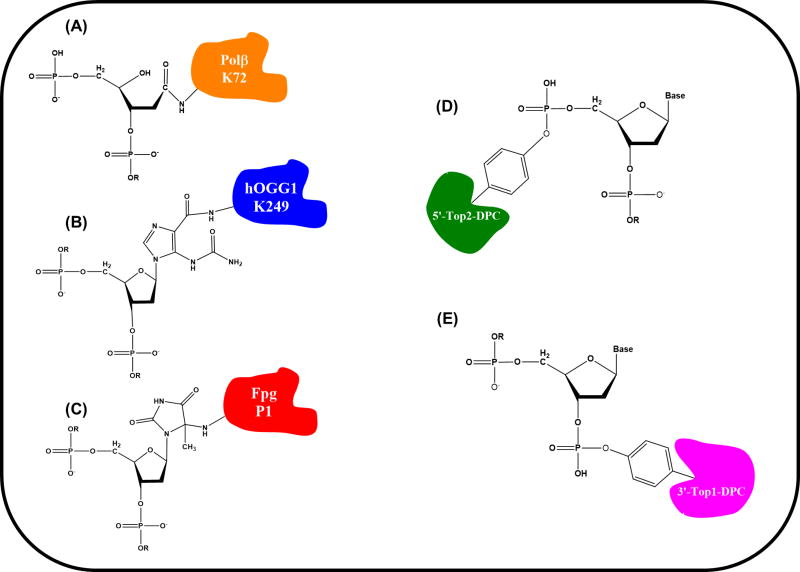

Figure 3. Representative Structures of Some Mechanism-based DPC.

Schematic depiction of the bonding chemistry of DPC due to DNA lesions or enzyme-inhibiting drugs (see main text). The structures are: Polβ-dL-DPC (A), hOGG1-Oxa-DPC (B), Fpg-cHyd-DPC (C), Top2-DPC (D), and Top1-DPC (E). The linking amino acid residues for Polβ, hOGG1 and Fpg are indicated using single-letter code (K = lysine; P = proline).

The finding that dL traps DNA repair lyases in DPC suggested that cells ought to have mechanisms to avoid this hazard. Consistent with this hypothesis, we showed that dL residues incubated with cell-free extracts are processed exclusively through an LP-BER mechanism that is dependent on the activity of Fen1 (14) (Fig. 1, step 2B), while the Polβ-DPC product itself is (not surprisingly) resistant to removal by LP-BER (14) (Fig. 1, step 2C). Consequently, a first line of defense against the genotoxicity of dL in DNA is its channeling into LP-BER, which highlights the importance of understanding the mechanism that governs this channeling. Conversely, these observations raise the question of whether imbalances in LP-BER protein expression, or conditions of oxidative stress generating large numbers of dL residues, could cause the formation of Polβ-DPC in vivo.

To address the above issue, we adapted an immunoslot-blot approach that detects topoisomerase DPC in cells treated with agents such as camptothecin and etoposide (50, 51). This procedure worked very well for detecting and quantifying oxidative Polβ-DPC in human and mouse cells challenged with oxidants, especially those that generate dL preferentially (52). Such dL-inducing oxidants include TPZ, which damages DNA selectively under hypoxia, and the compound Cu(OP)2, both generating significant levels of Polβ-DPC in a dose-dependent manner (52) (Fig. 2, step 1). Most importantly, the Polβ-DPC formation in vivo exhibited the mechanistic characteristics established in vitro: the DPC were not generated by non-oxidative agents such as methyl methane sulfonate; they required the activity of the Ape1 AP endonuclease (Fig. 1, step 1B); and they depended completely on the Polβ lyase active-site residue, lysine-72 (52).

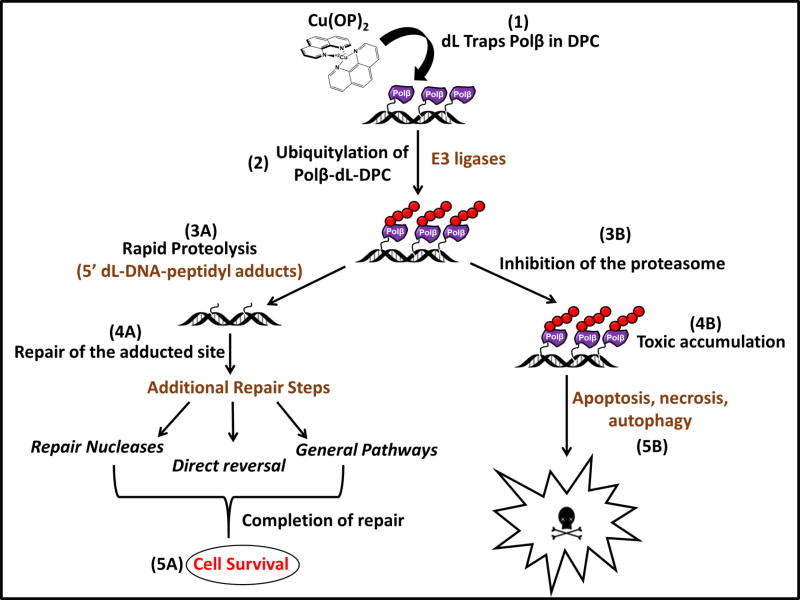

Figure 2. The Fate and Impact of Oxidative Polβ-DPC in vivo.

Exposure of cells to Cu(OP)2 results in robust Polβ-DPC formation (1). Polβ-DPC are subsequently targeted for ubiquitylation (2) and rapid proteolysis, which is expected to generate 5’-peptidyl-dL-DNA adducts (3A) that would be removed from the genome by DNA repair mechanisms being investigated (4A). Together, such repair processes would allow cells to escape the toxic effects of oxidative Polβ-DPC accumulation (5A). However, inhibition of the proteasome prevents removal of Polβ-DPC (3B), leading to their toxic accumulation (4B) with cell killing and perhaps other consequences (5B). Biological and mechanistic questions requiring further definition are highlighted in brown.

The repair and biological impact of oxidative Polβ-DPC

An attempt to identify a possible repair mechanism for Polβ-dL-DPC used HeLa whole-cell extracts competent for nucleotide excision repair (NER), which did not reveal any processing via NER (48). The authors suggested that the lack of NER repair was due to the presence of a pre-existing strand break at the DPC site (48). We approached this issue using the in vivo DPC assay, which revealed a role for the proteasome in the removing this lesion. Detectable oxidative Polβ-DPC were rapidly cleared from the genome of human and mouse cells, with half-times of 15–20 min (Fig. 2, step 3A). Treatment of cells containing Polβ-DPC with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 completely prevented this rapid removal, demonstrating proteolysis as a critical early step (52) (Fig. 2, step 3B). Involvement of the proteasome suggested that Polβ in oxidative DPC is targeted by ubiquitylation (Fig. 2, step 2), and indeed, a strong ubiquitin signal is found in the DPC of cells co-treated with Cu(OP)2 and MG132 (52) (Fig. 2, step 3B). In fact, Polβ-DPC seem to account for most (60–70%) of the ubiquitin trapped in oxidative DPC (52), which is very striking in that Polβ is a low-abundance protein in most cell types (53). Identifying the specific lysine residues ubiquitylated in oxidative Polβ-DPC is an important task ahead. Additionally, investigating the enzymes responsible for this targeting (i.e., E3 ligases, Fig. 2, step 2) and the downstream repair processes that repair the adducted site (specific nucleases, direct reversal, or general repair pathways; Fig. 2, step 4A) will also be critical for understanding how cells cope with this class of DPC (Fig. 2, step 5A).

The accumulation of unrepaired oxidative Polβ-DPC is cytotoxic (Fig. 2, steps 4B and 5B). We compared the survival of cells expressing wild-type Polβ to those expressing the K72A (lyase-deficient) form after a combined treatment with Cu(OP)2 and MG132, which demonstrated that cells with the lyase-deficient protein had substantially higher survival than those with WT-Polβ (52). Since other proteins (e.g., topoisomerases) are also covalently trapped on DNA in cells treated with Cu(OP)2 and MG132, this result underscores the specific biological impact of the Polβ-DPC. The cytotoxic effects may reflect not only the effect of the accumulated DNA lesion (Polβ-DPC), but also the depletion of a critical repair enzyme. Future studies will seek to uncover the mechanism of cytotoxicity-induced by this process in order to understand how this class of DPC contributes to cell death (Fig. 2, step 5B).

2. Additional BER Related DNA-protein Cross-links

DPC formation with dL and its β-elimination product by BER-associated lyases

Other enzymes that possess either 5’-dRp lyase or AP lyase activity have also been shown to form DPC in vitro with both dL and with its β–elimination product, butenolide (54). DNA glycosylases arrive at the site of base damage and initiate BER by removing base lesions; the bifunctional subclass of glycosylases may cleave the resulting AP site through their intrinsic lyase activities (55, 56). In vitro studies with dL-containing oligonucleotide substrates revealed initially that E. coli endonuclease III is trapped in DPC with the lesion without effecting cleavage of the DNA strand (46). Reactions of dL with E. coli Fpg or endonuclease VIII, yeast OGG1 or NTG2 (an endonuclease III homolog), and human OGG1 were all much less efficient than seen for E. coli endonuclease III (54). However, the AP lyases that can effect δ-elimination of AP sites (E. coli Fpg, NEIL1 and endonuclease VIII) are all robustly trapped by butenolide (54). Other in vitro studies indicate that (human) Nth1 and OGG1 form DPC when incubated with dL-DNA, while Fpg-DPC with dL were not detected (56). Together, these studies suggest that dL and its degradation product butenolide are capable of trapping enzymes with AP lyase activity in vitro, although their contribution in vivo has not been established.

Oxanine-DPC formation with BER enzymes in vitro

Certain base lesions can also instigate DPC formation with various BER enzymes and other proteins in vitro. Oxanine (Oxa) is a significant product of guanine nitrosation by nitric oxide, nitrous acid or N-nitrosoindoles and can form diverse types of DPC (57, 58). Reaction of Oxa-containing DNA duplexes (Oxa-DNA) with proteins containing nucleophilic lysine or arginine residues produces DPC for both types of linkage. This reactivity appears to be due to the aromatic lactone formed by Oxa, which would form a stable amide bond between lysine and the carbonyl derived from the guanine C1 (57, 58) (Fig. 3B). Oxa-DPC form not only with lyase-active enzymes, but also with histones and high mobility group (HMG) proteins (57). Similar to what has been observed for dL, trapping of Fpg, hOGG1 and endonuclease VIII was also observed for Oxa-DNA in vitro, but it is worth noting that the lyase-inactive glycosylase E. coli AlkA was also trapped, and at a rate only a few fold lower than seen for the lyases (54). Although Oxa has the potential to be a significant suicide substrate for DNA repair enzymes, the possible physiological impact of Oxa-DPC remains to be determined.

DPC formation with 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin in DNA

The thymine oxidation product 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin acts as a suicide substrate, forming DPC with E. coli Fpg and endonuclease VIII, and with human NEIL1 (59). The crystal structure of a stabilized form of an Fpg-hydantoin DPC revealed cross-linking between the Fpg N-terminal proline (that enzyme’s lyase nucleophile) and the C5 position of the hydantoin (Fig. 3C). As for Oxa, the biological as opposed to in vitro significance of these DPC needs to be addressed.

Topoisomerase-DPC formation in DNA with BER lesions in vitro and in vivo

DNA topoisomerases are capable of being trapped as the covalent DNA-protein intermediates that are part of their normal catalytic cycle, so-called topoisomerase cleavage complexes [(reviewed in (60)]. Under physiological conditions, topoisomerases break and rapidly rejoin DNA strands to relieve topological strain. Eukaryotic topoisomerase I (Top1) accomplishes this by nicking one DNA strand with the formation of a tyrosyl ester to the 3’-phosphate, followed by rejoining the DNA termini and releasing the enzyme. Topoisomerase 2 (Top2) carries out analogous reactions involving both strands, forming tyrosyl esters (one per subunit of the homodimer) with the 5’-phosphoryl termini, which are reclosed to release the enzyme. Normally, the Top1- and Top2-DPC intermediates are quickly resolved, but they can become trapped in various ways and are associated with substantial cytotoxicity (Fig. 3D, E).

Reflecting this cytotoxicity, the well-known topoisomerase poisons camptothecin (against Top1) and etoposide (against Top2) are also widely used anticancer agents. However, DNA damage in general can also disrupt the catalytic cycle of topoisomerases, evidently through their effects on DNA structure, rather than the chemistry of the topoisomerases per se. Lesions such as 8-oxoguanine, AP sites, single-strand breaks and uracil residues, when placed suitably close to a topoisomerase cleavage site, lead to DPC formation in vitro (61–63). These effects are also reflected in vivo when cells are exposed to agents that generate other DNA lesions. For example, mammalian cells lacking the O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase, the enzyme responsible for removing alkyl groups from the 6-position of guanines, are sensitive to treatment with the alkylating agent, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), and accumulate more Top1-DPC than wild-type cells (64). Furthermore, yeast cells overexpressing human Top1 display hypersensitivity to MNNG exposure, whereas knocking out Top1 confers resistance to the effects MNNG treatment (64). BER agents such as temozolomide, a clinically relevant methylating drug that forms O6-methylguanine, 7-methylguanine, and 3-methyladenine DNA adducts also induces robust Top2-DPC formation in cells (65).

Consistent with these broad effects, both yeast and mouse cells challenged with the oxidant H2O2 display markedly increased levels of Top1-DPC (66). In accord with these data, we found that Cu(OP)2 also induces Top1 and Top2-DPC, which can accumulate to a similar extent to that observed in camptothecin- or etoposide-treated cells (52). In this case, there could be additional effects of the o-phenanthroline ligands of Cu(OP)2, as previously suggested by molecular simulation studies (67). Whatever the case, the contribution of these abundant proteins to the ubiquitin trapped in oxidative DPC is still less than that found for the less abundant Polβ protein.

3. Closing Remarks and Future Prospects

Although the details of oxidative Polβ-DPC formation and clearance in vivo are coming into focus, much information is lacking regarding the trapping of other DNA repair enzymes involved in the BER process. DPC formation with BER repair factors such as the bifunctional DNA glycosylases has been extensively studied in vitro, but much work remains to be done to understand the formation and fate of glycosylase-DPC involving dL, Oxa and 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin in the genome. The in vivo formation of oxidative DPC by other DNA repair enzymes that harbor 5’-dRp or AP lyase activity such as DNA polymerase λ (68), DNA polymerase γ (69), DNA polymerases of the Y-family (κ, ι, and η) (70) Ku antigen (71, 72) and PARP1 (73, 74) have also been demonstrated in vivo from work in our lab (unpublished data), but the mechanism(s) by which they are cleared from cells has yet to be established. Since DNA repair enzymes with AP lyase activity are required for cell survival and are often aberrantly expressed in neoplastic tissue (75), oxidative trapping of these enzymes may prove to be an effective novel anticancer strategy in the future. Thus, identifying key protein targets involved in oxidative DPC formation, and the mechanisms responsible for their potential removal in vivo, should open up new and significant avenues of research in this regard.

Acknowledgments

Our work was supported by doctoral fellowship F31GM109747 to JLQ, and grants from the NIH to BD. We are grateful to our fellow lab members for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- Cu(OP)2

1,10 copper-o-phenanthroline

- dL

2-deoxyribonolactone

- 5’-dRp

5’-deoxyribose-5-phosphate

- AP

apurinic/apyrimidinic (abasic)

- Polβ

DNA polymerase β

- DPC

DNA-protein crosslink

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- Oxa

oxanine

- TPZ

tirapazamine

- Top1

topoisomerase 1

- Top2

topoisomerase 2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chan SW, Dedon PC. The Biological and Metabolic Fates of Endogenous DNA Damage Products. Journal of Nucleic Acids. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/929047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11(19):3610–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Sites in Genomic DNA of Mammalian Tissues. Cancer Research. 1999;59(11):2522–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura J, Walker VE, Upton PB, Chiang S-Y, Kow YW, Swenberg JA. Highly Sensitive Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Site Assay Can Detect Spontaneous and Chemically Induced Depurination under Physiological Conditions. Cancer Research. 1998;58(2):222–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace SS. Base excision repair: A critical player in many games. DNA Repair. 2014;(0) doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bauer NC, Corbett AH, Doetsch PW. The current state of eukaryotic DNA base damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidorenko VS, Zharkov DO. Role of base excision repair DNA glycosylases in hereditary and infectious human diseases. Mol Biol. 2008;42(5):794–805. doi: 10.1134/S0026893308050166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demple B, Herman T, Chen DS. Cloning and expression of APE, the cDNA encoding the major human apurinic endonuclease: definition of a family of DNA repair enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88(24):11450–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demple B, Sung J-S. Molecular and biological roles of Ape1 protein in mammalian base excision repair. DNA Repair. 2005;4(12):1442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto Y, Kim K. Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase beta during DNA repair. Science. 1995;269(5224):699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.7624801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobol RW, Horton JK, Kuhn R, Gu H, Singhal RK, Prasad R, Rajewsky K, Wilson SH. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-[beta] in base-excision repair. Nature. 1996;379(6561):183–6. doi: 10.1038/379183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad R, Beard WA, Chyan JY, Maciejewski MW, Mullen GP, Wilson SH. Functional Analysis of the Amino-terminal 8-kDa Domain of DNA Polymerase β as Revealed by Site-directed Mutagenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(18):11121–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podlutsky AJ, Dianova II, Podust VN, Bohr VA, Dianov GL. Human DNA polymerase β initiates DNA synthesis during long-patch repair of reduced AP sites in DNA. The EMBO journal. 2001;20(6):1477–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung JS, DeMott MS, Demple B. Long-patch base excision DNA repair of 2-deoxyribonolactone prevents the formation of DNA-protein cross-links with DNA polymerase beta. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39095–103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P, Qian L, Sung J-S, de Souza-Pinto NC, Zheng L, Bogenhagen DF, Bohr VA, Wilson DM, Shen B, Demple B. Removal of Oxidative DNA Damage via FEN1-Dependent Long-Patch Base Excision Repair in Human Cell Mitochondria. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28(16):4975–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.00457-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dianov GL, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Bohr VA. Role of DNA Polymerase β in the Excision Step of Long Patch Mammalian Base Excision Repair. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(20):13741–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma W, Panduri V, Sterling JF, Van Houten B, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The Transition of Closely Opposed Lesions to Double-Strand Breaks during Long-Patch Base Excision Repair Is Prevented by the Coordinated Action of DNA Polymerase δ and Rad27/Fen1. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(5):1212–21. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01499-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad R, Lavrik OI, Kim S-J, Kedar P, Yang X-P, Vande Berg BJ, Wilson SH. DNA Polymerase β-mediated Long Patch Base Excision Repair: POLY(ADP-RIBOSE) POLYMERASE-1 STIMULATES STRAND DISPLACEMENT DNA SYNTHESIS. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(35):32411–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stucki M, Pascucci B, Parlanti E, Fortini P, Wilson S, Hübscher U, Dogliotti E. Mammalian base excision repair by DNA polymerases δ and ε. Oncogene. 1998;17(7) doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto Y, Kim K, Bogenhagen DF. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen-dependent abasic site repair in Xenopus laevis oocytes: an alternative pathway of base excision DNA repair. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1994;14(9):6187–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klungland A, Lindahl T. Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision-repair: reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1) The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(11):3341–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frosina G, Fortini P, Rossi O, Carrozzino F, Raspaglio G, Cox LS, Lane DP, Abbondandolo A, Dogliotti E. Two Pathways for Base Excision Repair in Mammalian Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(16):9573–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMott MS, Beyret E, Wong D, Bales BC, Hwang JT, Greenberg MM, Demple B. Covalent trapping of human DNA polymerase beta by the oxidative DNA lesion 2-deoxyribonolactone. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(10):7637–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedon PC. The Chemical Toxicology of 2-Deoxyribose Oxidation in DNA. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;21(1):206–19. doi: 10.1021/tx700283c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhaese H-J, Freese E. Chemical analysis of DNA alterations: I. Base liberation and backbone breakage of DNA and oligodeoxyadenylic acid induced by hydrogen peroxide and hydroxylamine. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis. 1968;155(2):476–90. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(68)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roginskaya M, Bernhard WA, Marion RT, Razskazovskiy Y. The release of 5-methylene-2-furanone from irradiated DNA catalyzed by cationic polyamines and divalent metal cations. Radiat Res. 2005;163(1):85–9. doi: 10.1667/rr3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roginskaya M, Razskazovskiy Y. Selective radiation-induced generation of 2-deoxyribonolactone lesions in DNA mediated by aromatic iodonium derivatives. Radiat Res. 2009;171(3):342–8. doi: 10.1667/RR1574.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan W, Chen B, Wang L, Taghizadeh K, Demott MS, Dedon PC. Quantification of the 2-deoxyribonolactone and nucleoside 5'-aldehyde products of 2-deoxyribose oxidation in DNA and cells by isotope-dilution gas chromatography mass spectrometry: differential effects of gamma-radiation and Fe2+-EDTA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(17):6145–53. doi: 10.1021/ja910928n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kappen LS, Goldberg IH. Identification of 2-deoxyribonolactone at the site of neocarzinostatin-induced cytosine release in the sequence d(AGC) Biochemistry. 1989;28(3):1027–32. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Greenberg MM. Selective Detection of 2-Deoxyribonolactone in DNA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127(9):2806–7. doi: 10.1021/ja0426185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels JS, Gates KS, Tronche C, Greenberg MM. Direct Evidence for Bimodal DNA Damage Induced by Tirapazamine. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 1998;11(11):1254–7. doi: 10.1021/tx980184j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang J-T, Greenberg MM, Fuchs T, Gates KS. Reaction of the Hypoxia-Selective Antitumor Agent Tirapazamine with a C1‘-Radical in Single-Stranded and Double-Stranded DNA: The Drug and Its Metabolites Can Serve as Surrogates for Molecular Oxygen in Radical- Mediated DNA Damage Reactions†. Biochemistry. 1999;38(43):14248–55. doi: 10.1021/bi991488n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhury G, Junnotula V, Daniels JS, Greenberg MM, Gates KS. DNA Strand Damage Product Analysis Provides Evidence That the Tumor Cell-Specific Cytotoxin Tirapazamine Produces Hydroxyl Radical and Acts as a Surrogate for O2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129(42):12870–7. doi: 10.1021/ja074432m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goyne TE, Sigman DS. Nuclease activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-copper ion. Chemistry of deoxyribose oxidation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1987;109(9):2846–8. doi: 10.1021/ja00243a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijler MM, Zelenko O, Sigman DS. Chemical Mechanism of DNA Scission by (1,10-Phenanthroline)copper. Carbonyl Oxygen of 5-Methylenefuranone Is Derived from Water. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119(5):1135–6. doi: 10.1021/ja962409n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang J-T, Tallman KA, Greenberg MM. The reactivity of the 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion in single-stranded DNA and its implication in reaction mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(19):3805–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y-j, DeMott MS, Hwang JT, Greenberg MM, Demple B. Action of human apurinic endonuclease (Ape1) on C1′-oxidized deoxyribose damage in DNA. DNA Repair. 2003;2(2):175–85. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotera M, Roupioz Y, Defrancq E, Bourdat A-G, Garcia J, Coulombeau C, Lhomme J. The 7-Nitroindole Nucleoside as a Photochemical Precursor of 2′-Deoxyribonolactone: Access to DNA Fragments Containing This Oxidative Abasic Lesion. Chemistry – A European Journal. 2000;6(22):4163–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001117)6:22<4163::aid-chem4163>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenox HJ, McCoy CP, Sheppard TL. Site-Specific Generation of Deoxyribonolactone Lesions in DNA Oligonucleotides. Organic Letters. 2001;3(15):2415–8. doi: 10.1021/ol016255e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tronche C, Goodman BK, Greenberg MM. DNA damage induced via independent generation of the radical resulting from formal hydrogen atom abstraction from the C12-position of a nucleotide. Chemistry & biology. 1998;5(5):263–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Y, Sheppard TL. Half-Life and DNA Strand Scission Products of 2-Deoxyribonolactone Oxidative DNA Damage Lesions. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2004;17(2):197–207. doi: 10.1021/tx034197v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jourdan M, Garcia J, Defrancq E, Kotera M, Lhomme J. 2‘-Deoxyribonolactone Lesion in DNA: Refined Solution Structure Determined by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Molecular Modeling. Biochemistry. 1999;38(13):3985–95. doi: 10.1021/bi982743r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H, Greenberg MM. Synthesis and Analysis of Oligonucleotides Containing Abasic Site Analogues. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2008;73(7):2695–703. doi: 10.1021/jo702614p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroeger KM, Jiang YL, Kow YW, Goodman MF, Greenberg MM. Mutagenic Effects of 2-Deoxyribonolactone in Escherichia coli. An Abasic Lesion That Disobeys the A-Rule†. Biochemistry. 2004;43(21):6723–33. doi: 10.1021/bi049813g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kow YW, Bao G, Minesinger B, Jinks-Robertson S, Siede W, Jiang YL, Greenberg MM. Mutagenic effects of abasic and oxidized abasic lesions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(19):6196–202. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto M, Greenberg MM, Kow YW, Hwang JT, Cunningham RP. The 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion produced in DNA by neocarzinostatin and other damaging agents forms cross-links with the base-excision repair enzyme endonuclease III. J Am Chem Soc. 2001 Apr 4;123(13):3161–2. doi: 10.1021/ja003354z. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Son M-Y, Jun H-I, Lee K-G, Demple B, Sung J-S. Biochemical Evaluation of Genotoxic Biomarkers for 2-Deoxyribonolactone-Mediated Cross-Link Formation with Histones. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 2009;72(21–22):1311–7. doi: 10.1080/15287390903212402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung JS, Park IK. Formation of DNA-protein cross-links mediated by C1'-oxidized abasic lesion in mouse embryonic fibroblast cell-free extracts. Integrative Biosciences. 2005;9(2):79–85. doi: 10.1080/17386357.2005.9647255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sung JS, Demple B. Analysis of Base Excision DNA Repair of the Oxidative Lesion 2-Deoxyribonolactone and the Formation of DNA–Protein Cross-Links. In: Campbell J, Modrich P, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 48–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiianitsa K, Maizels N. Ultrasensitive isolation, identification and quantification of DNA–protein adducts by ELISA-based RADAR assay. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiianitsa K, Maizels N. A rapid and sensitive assay for DNA–protein covalent complexes in living cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quiñones JL, Thapar U, Yu K, Fang Q, Sobol RW, Demple B. Enzyme mechanism-based, oxidative DNA–protein cross-links formed with DNA polymerase β in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(28):8602–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501101112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton JK, Srivastava DK, Zmudzka BZ, Wilson SH. Strategic down-regulation of DNA polymerase β by antisense RNA sensitizes mammalian cells to specific DNA damaging agents. Nucleic Acids Research. 1995;23(19):3810–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.19.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kroeger KM, Hashimoto M, Kow YW, Greenberg MM. Cross-Linking of 2-Deoxyribonolactone and Its β-Elimination Product by Base Excision Repair Enzymes†. Biochemistry. 2003;42(8):2449–55. doi: 10.1021/bi027168c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacobs A, Schär P. DNA glycosylases: in DNA repair and beyond. Chromosoma. 2012;121(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0347-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ide H, Kotera M. Human DNA Glycosylases Involved in the Repair of Oxidatively Damaged DNA. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2004;27(4):480–5. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakano T, Terato H, Asagoshi K, Masaoka A, Mukuta M, Ohyama Y, Suzuki T, Makino K, Ide H. DNA-Protein Cross-link Formation Mediated by Oxanine: A NOVEL GENOTOXIC MECHANISM OF NITRIC OXIDE-INDUCED DNA DAMAGE. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(27):25264–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H-JC, Hsieh C-J, Shen L-C, Chang C-M. Characterization of DNA−Protein Cross-Links Induced by Oxanine: Cellular Damage Derived from Nitric Oxide and Nitrous Acid†. Biochemistry. 2007;46(13):3952–65. doi: 10.1021/bi0620398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Le Bihan Y-V, Angeles Izquierdo M, Coste F, Aller P, Culard F, Gehrke TH, Essalhi K, Carell T, Castaing B. 5-Hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin DNA lesion, a molecular trap for DNA glycosylases. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pommier Y, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase-Induced DNA Damage. In: Pommier Y, editor. DNA Topoisomerases and Cancer. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2012. pp. 145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kingma PS, Corbett AH, Burcham PC, Marnett LJ, Osheroff N. Abasic Sites Stimulate Double-stranded DNA Cleavage Mediated by Topoisomerase II: DNA LESIONS AS ENDOGENOUS TOPOISOMERASE II POISONS. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(37):21441–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pourquier P, Ueng L-M, Kohlhagen G, Mazumder A, Gupta M, Kohn KW, Pommier Y. Effects of Uracil Incorporation, DNA Mismatches, and Abasic Sites on Cleavage and Religation Activities of Mammalian Topoisomerase I. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(12):7792–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sabourin M, Osheroff N. Sensitivity of human type II topoisomerases to DNA damage: stimulation of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage by abasic, oxidized and alkylated lesions. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(9):1947–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pourquier P, Waltman JL, Urasaki Y, Loktionova NA, Pegg AE, Nitiss JL, Pommier Y. Topoisomerase I-mediated Cytotoxicity of N-Methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine: Trapping of Topoisomerase I by the O6-Methylguanine. Cancer Research. 2001;61(1):53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan L, Bulgar A, Miao Y, Mahajan V, Donze JR, Gerson SL, Liu L. Combined Treatment with Temozolomide and Methoxyamine: Blocking Apurininc/Pyrimidinic Site Repair Coupled with Targeting Topoisomerase IIα. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(5):1532–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-06-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daroui P, Desai SD, Li T-K, Liu AA, Liu LF. Hydrogen Peroxide Induces Topoisomerase I-mediated DNA Damage and Cell Death. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(15):14587–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arjmand F, Parveen S, Afzal M, Toupet L, Ben Hadda T. Molecular drug design, synthesis and crystal structure determination of CuII–SnIV heterobimetallic core: DNA binding and cleavage studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;49:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.García-Díaz M, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Blanco L. Identification of an Intrinsic 5′- Deoxyribose-5-phosphate Lyase Activity in Human DNA Polymerase λ. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(37):34659–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Longley MJ, Prasad R, Srivastava DK, Wilson SH, Copeland WC. Identification of 5′-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase γ and its role in mitochondrial base excision repair in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(21):12244–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haracska L, Prakash L, Prakash S. A mechanism for the exclusion of low-fidelity human Y-family DNA polymerases from base excision repair. Genes & Development. 2003;17(22):2777–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1146103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roberts SA, Strande N, Burkhalter MD, Strom C, Havener JM, Hasty P, Ramsden DA. Ku is a 5'-dRP/AP lyase that excises nucleotide damage near broken ends. Nature. 2010;464(7292):1214–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08926. doi: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v464/n7292/suppinfo/nature08926_S1.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strande NT, Carvajal-Garcia J, Hallett RA, Waters CA, Roberts SA, Strom C, Kuhlman B, Ramsden DA. Requirements for 5′dRP/AP lyase activity in Ku. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khodyreva SN, Prasad R, Ilina ES, Sukhanova MV, Kutuzov MM, Liu Y, Hou EW, Wilson SH, Lavrik OI. Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site recognition by the 5'-dRP/AP lyase in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(51):22090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009182107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prasad R, Horton JK, Chastain PD, Gassman NR, Freudenthal BD, Hou EW, Wilson SH. Suicidal cross-linking of PARP-1 to AP site intermediates in cells undergoing base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/nar/gku288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wallace SS, Murphy DL, Sweasy JB. Base excision repair and cancer. Cancer Letters. 2012;327(1–2):73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]