Abstract

Background:

The management and outcomes of preterm births can vary greatly even among developed nations with the same access to medicine, technology and expertise. We aimed to compare aspects of obstetrical management and mortality for preterm infants in France and Ontario, Canada.

Methods:

The Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Information System in Ontario and Épidémiologique sur les petits âges gestationnels (EPIPAGE-2) in France collected information on maternal demographics, obstetrical characteristics, obstetrical interventions and neonatal outcomes for infants born between 22 and 34 weeks gestation. We used standardized covariate definitions and extracted data from 2011 (for EPIPAGE-2) and from 2012 and 2013 (for BORN) to conduct a cohort study comparing the 2 data sets (stratified into gestational age groups of 22–26, 27–31 and 32–34 wk) using multivariable logistic regression models.

Results:

Mothers in the BORN cohort were older (30.7 yr v. 29.6 yr) but less likely to have gestational hypertension (13.4% v. 17.9%) than those in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort. Infants from EPIPAGE-2 had lower birth weights (1.3 kg v. 1.5 kg) and were more likely to be born in an institution with level 3 care (71.9% v. 55.8%). After adjustment for these differences, there was significantly higher neonatal mortality among infants from EPIPAGE-2 in the 22–26 week gestation age group (adjusted odds ratio 2.81; 95% confidence interval 1.17 to 6.74).

Interpretation:

Even after we adjusted for both intrinsic population differences and differences in management between Ontario and France, we found a higher rate of neonatal mortality at earlier gestational ages in France. This may be related to differences in ethical approaches and/or postnatal management and should be explored further.

Preterm births (< 37 weeks gestation) account for more than 80% of all perinatal complications and deaths, and increasing numbers of preterm infants are being born annually worldwide.1 In Canada, preterm births represented 7.8% of all live births in 2010, compared with 6.6% in 1991.1 Numbers have been increasing in other countries as well, with France reporting a rate of 7.5% of all live births in 2016 compared with 6.0% in 1995.2 In general, survival of infants born at less than 32 weeks of gestation has improved in developed nations because of the widespread use of surfactant treatment for respiratory distress syndrome, administration of antenatal glucocorticoids and new ventilation strategies.3–6 However, a review of published data from developed nations suggests that the outcomes of preterm infants can vary greatly between countries, especially at the lower gestational ages.7,8 This is probably related to variations in practice and the approach to the management of preterm births. It is extremely difficult to compare these differences via randomized controlled trials because of ethical concerns, and the link between obstetrical interventions and outcomes needs to be further explored. Fortunately, many countries have developed large-scale databases/registries to track births and outcomes of preterm infants. These often include in-depth information about maternal and neonatal variables as well as elements associated with obstetrical management and delivery. By using these data sets, we are able to compare management approaches and outcomes of preterm infants between countries and determine if practice variations are associated with differences in outcomes. France and Ontario both have large-scale data sets on preterm infants. For this study, our primary objective was to compare the obstetrical interventions and rate of neonatal deaths of preterm deliveries (≤ 34 wk) in Ontario and France, using these data sets.

Methods

Study populations

We performed a cohort study using data sets from 2 population-based birth cohorts: (a) the Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Information System representing Ontario, Canada, and (b) the second cycle of an epidemiological study on a cohort of low gestational age infants (Épidémiologique sur les petits âges gestationnels; EPIPAGE-2) representing France. The data sets were chosen for comparison because of the completeness of data capture and similarities between the 2 populations in terms of socioeconomic distribution and access to modern medicine and technology.9 Both data sources are described in more detail elsewhere.10–12 EPIPAGE-2 is a population-based sample of preterm infants (≤ 34 completed gestational wk) born between March and November 2011, whereas BORN Ontario is an ongoing birth registry that captures all births in the province of Ontario. Because the population of France is larger than that of Ontario, EPIPAGE-2 recruited more preterm infants over a shorter period of time. For this reason, in creating our cohort from BORN Ontario we included preterm births over an 18-month period (April 2012 and December 2013). This period was chosen to provide sufficient statistical power, ensuring a minimum of 200 records per gestational week category. Any live-born preterm (≤ 34 wk gestation) infant born within the study periods was eligible for inclusion. We excluded any infants with identified congenital anomalies. Neonatal deaths included deaths up to 5 months of age to include the duration of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stay for babies born extremely preterm (< 28 wk gestation).

Comorbidities and covariates

We compared maternal characteristics such as age, morbidity (any chronic medical condition for which the mother had been diagnosed, or for which she was being treated, before pregnancy, such as psychiatric conditions, kidney disease and cardiac disease), pregnancy-related complications such as gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension, obstetrical characteristics such as multifetal gestation and delivery in an institution with a NICU that provides level 3 care, obstetrical interventions such as assisted reproductive technology, cesarean delivery, induction of labour and use of antenatal steroids, and neonatal characteristics such as birth weight and infant sex. All variable definitions were compared to ensure matching between the 2 cohorts. Covariates were chosen on the basis of clinical relevance and we could not identify additional variables related to neonatal mortality. To be consistent with previous EPIPAGE-2 publications, we categorized gestational age into 3 discrete groups: (a) 22–26 weeks, (b) 27–31 weeks and (c) 32–34 weeks. Both cohorts used a combination of dating ultrasounds and the date of the last menstrual period to estimate gestational age. To ensure complete capture of all neonatal deaths at lower gestational ages in BORN, information on neonatal deaths was supplemented with data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information,12 a Canada-wide system that independently collects health administrative data. Only live-born infants were used for descriptive characteristics and as the denominator for analyzing neonatal deaths.

Statistical analysis

To facilitate data analysis, EPIPAGE-2 data were securely transferred directly from EPIPAGE-2 to BORN Ontario servers. Live births, stillbirths and neonatal deaths were stratified by gestational age, and summary statistics were used to represent covariates stratified by gestational age groups between Ontario and France. At a 95% level of significance and 80% power, the planned analysis was expected to detect a minimum difference of 5% in neonatal deaths between Ontario and France. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test or χ2 test of homogeneity and standardized difference was used to highlight the magnitude of these disparities. Sample weighting was not necessary to compare the population-based sample approach used by EPIPAGE-2 with that used by BORN Ontario, as the comparisons were within gestational age groups. As such, the summary estimates were unbiased. However, for overall analyses that combined gestational age groups, sample weightings were employed to correct for stratified sampling methodologies used by EPIPAGE-2. Neonatal death for all live births was compared between EPIPAGE-2 and BORN using sample-weighted crude and multivariable logistic regression models. Models were adjusted for clinically important covariates on the basis of clinical rationale and the results of the univariate analysis. Data were adjusted in 2 stages: first for non-modifiable intrinsic characteristics, including maternal age, gestational hypertension, assisted reproductive technology, infant birth weight and multifetal pregnancy, and second for variables related to obstetrical and neonatal care, including birth in a centre with a level 3 NICU, antenatal corticosteroids and cesarean delivery. These covariates are well established in the literature to be factors affecting neonatal mortality.11,13–15 Unweighted models were repeated within each gestational age group and for deaths occurring within 1 and 5 months of birth.

Data management and analysis were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and statistical significance was evaluated with a 2-sided p value of 0.05. The STROBE cohort reporting guidelines were used.16

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the research ethics boards of the University of Ottawa and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. EPIPAGE-2 was approved by the National Data Protection Authority (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés no. 911009) and by appropriate ethics committees.

Results

A total of 14 760 neonatal records were included in the study: 8278 from BORN (Table 1) and 6482 from EPIPAGE-2 (Table 2). There were 1067 neonatal deaths (365 from BORN and 702 from EPIPAGE-2). Univariate comparisons of maternal/obstetrical and neonatal characteristics are shown in Table 3 (stratified by gestational age). On average, mothers in the BORN cohort were older than those in the EPIPAGE-2 cohort (30.7 yr v. 29.6 yr) but less likely to have gestational hypertension (13.4% v. 17.9%). Infants from EPIPAGE-2 had lower birth weights than infants from BORN (1.3 kg v. 1.5 kg). There were also differences in other baseline characteristics such as multifetal pregnancies and use of assisted reproductive technology especially in certain gestational age groups.

Table 1:

Births in Ontario by gestational age (April 2012 to December 2013)

| Gestational age, wk | Total no. of births | No. of stillbirths (%)* | No. of live births | No. of neonatal deaths (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 172 | 82 (47.6) | 90 | 68 (75.6) |

| 23 | 195 | 58 (29.7) | 137 | 89 (65.0) |

| 24 | 210 | 40 (19.0) | 170 | 57 (33.5) |

| 25 | 273 | 43 (15.7) | 230 | 34 (14.8) |

| 26 | 270 | 29 (10.7) | 241 | 26 (10.8) |

| 22–26 | 1120 | 252 | 868 | 274 |

| 27 | 296 | 28 (9.5) | 268 | 21 (7.8) |

| 28 | 298 | 23 (7.7) | 275 | 7 (2.5) |

| 29 | 402 | 48 (11.9) | 354 | 13 (3.7) |

| 30 | 499 | 18 (3.6) | 481 | 6 (1.2) |

| 31 | 731 | 35 (4.8) | 696 | 10 (1.4) |

| 27–31 | 2226 | 152 | 2074 | 57 |

| 32 | 1000 | 39 (3.9) | 961 | 12 (1.2) |

| 33 | 1474 | 38 (2.6) | 1436 | 13 (0.9) |

| 34 | 2458 | 45 (1.8) | 2413 | 9 (0.4) |

| 32–34 | 4932 | 122 | 4810 | 34 |

| Total | 8278 | 526 | 7752 | 365 |

The denominator for the percentages is the total no. of births for each gestational age group.

Table 2:

Births in France by gestational age (March 2011 to November 2011)

| Gestational age, wk | Total no. of births | No. of stillbirths (%)* | No. of live births | No. of neonatal deaths (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 377 | 319 (84.6) | 58 | 58 (100.0) |

| 23 | 371 | 282 (76.0) | 89 | 88 (98.9) |

| 24 | 364 | 178 (48.9) | 186 | 128 (68.8) |

| 25 | 407 | 99 (24.3) | 308 | 126 (40.9) |

| 26 | 498 | 85 (17.1) | 413 | 102 (24.7) |

| 22–26 | 2017 | 963 | 1054 | 502 |

| 27 | 467 | 67 (14.3) | 400 | 71 (17.8) |

| 28 | 520 | 63 (12.1) | 457 | 46 (10.1) |

| 29 | 557 | 48 (8.6) | 509 | 23 (4.5) |

| 30 | 756 | 75 (9.9) | 681 | 21 (3.1) |

| 31 | 931 | 69 (7.4) | 862 | 26 (3.0) |

| 27–31 | 3231 | 322 | 2909 | 187 |

| 32 | 281 | 10 (3.6) | 271 | 5 (1.8) |

| 33 | 363 | 9 (2.5) | 354 | 3 (0.8) |

| 34 | 590 | 9 (1.5) | 581 | 5 (0.9) |

| 32–34 | 1234 | 28 | 1206 | 13 |

| Total | 6482 | 1313 | 5169 | 702 |

The denominator for the percentages is the total no. of births for each gestational age group.

Table 3:

Maternal/obstetrical and neonatal characteristics stratified by gestational age

| Characteristic; gestational age, wk | Ontario n = 6543 |

France n = 4300 |

Standardized difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, yr, mean ± SD | |||

| 22–26 | 30.43 ± 5.98 | 29.10 ± 5.96 | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.26) |

| 27–31 | 31.08 ± 6.01 | 29.67 ± 6.04 | 0.23 (0.19 to 0.27) |

| 32–34 | 30.67 ± 5.85 | 29.94 ± 5.54 | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.17) |

| Morbidity,* no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 350 (47.36) | 436 (49.32) | −0.08 (−0.12 to −0.04) |

| 27–31 | 770 (46.03) | 1114 (45.71) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) |

| 32–34 | 1756 (44.74) | 447 (45.66) | −0.04 (−0.08 to 0.00) |

| Gestational diabetes, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 21 (3.49) | 31 (3.88) | −0.11 (−0.15 to −0.07) |

| 27–31 | 120 (8.50) | 190 (8.45) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) |

| 32–34 | 323 (9.13) | 88 (9.78) | −0.08 (−0.12 to −0.04) |

| Gestational hypertension, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 52 (8.51) | 104 (11.76) | −0.36 (−0.40 to −0.32) |

| 27–31 | 236 (16.65) | 585 (24.00) | −0.46 (−0.50 to −0.42) |

| 32–34 | 541 (14.93) | 175 (17.88) | −0.22 (−0.26 to −0.18) |

| Assisted reproductive technology, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 83 (11.66) | 130 (15.40) | −0.32 (−0.36 to −0.28) |

| 27–31 | 186 (11.50) | 266 (11.32) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) |

| 32–34 | 388 (10.06) | 122 (12.90) | −0.28 (−0.32 to −0.24) |

| Cesarean delivery, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 285 (37.30) | 316 (36.41) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) |

| 27–31 | 980 (56.39) | 1671 (69.34) | −0.56 (−0.60 to −0.52) |

| 32–34 | 1924 (47.61) | 523 (53.97) | −0.26 (−0.30 to −0.22) |

| Induction of labour, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 60 (7.85) | 28 (3.24) | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.93) |

| 27–31 | 53 (3.05) | 41 (1.75) | 0.56 (0.52 to 0.60) |

| 32–34 | 431 (10.67) | 94 (9.98) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) |

| Multifetal pregnancy, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 103 (13.48) | 167 (18.89) | −0.40 (−0.44 to −0.36) |

| 27–31 | 308 (17.72) | 455 (18.67) | −0.06 (−0.10 to −0.02) |

| 32–34 | 743 (18.39) | 219 (22.37) | −0.25 (−0.29 to −0.21) |

| Antenatal steroids, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 444 (60.33) | 552 (64.71) | −0.19 (−0.23 to −0.15) |

| 27–31 | 1292 (78.30) | 1987 (83.17) | −0.31 (−0.35 to −0.27) |

| 32–34 | 1728 (45.43) | 685 (71.58) | −1.16 (−1.20 to −1.12) |

| Level 3 care, no. (col %†) | |||

| 22–26 | 513 (68.04) | 704 (79.64) | −0.61 (−0.65 to −0.57) |

| 27–31 | 1112 (64.43) | 2064 (84.69) | −1.13 (−1.17 to −1.09) |

| 32–34 | 1186 (29.52) | 490 (50.05) | −0.90 (−0.94 to −0.86) |

| Birth weight, g, mean ± SD | |||

| 22–26 | 906 ± 710 | 748 ± 161 | 0.36 (0.32 to 0.40) |

| 27–31 | 1408 ± 423 | 1275 ± 326 | 0.36 (0.32 to 0.40) |

| 32–34 | 2123 ± 458 | 1982 ± 384 | 0.33 (0.29 to 0.37) |

| Male sex, no. (col %‡) | |||

| 22–26 | 489 (56.34) | 558 (52.99) | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.18) |

| 27–31 | 1131 (54.64) | 1537 (52.84) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) |

| 32–34 | 2666 (55.50) | 647 (53.69) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation.

Any chronic medical condition for which the mother had been diagnosed, or for which she was being treated, before pregnancy, such as psychiatric conditions, kidney disease and cardiac disease.

col % = column percentage, calculated with a denominator of mothers within the respective gestational age group.

col % = column percentage, calculated with a denominator of infants within the respective gestational age group.

In terms of obstetrical management, more women in France received completed courses of antenatal steroids for infants born at 27–34 weeks gestation. In addition, a greater number of preterm infants were born in hospitals with level 3 NICU care in France than in Ontario across all gestational ages (71.9% v. 55.8%). There were also differences in obstetrical management of preterm births in certain gestational age groups. For example, France had a higher rate of cesarean delivery for infants born at more than 27 weeks gestation and Ontario had a higher rate of labour induction for infants born at less than 32 weeks.

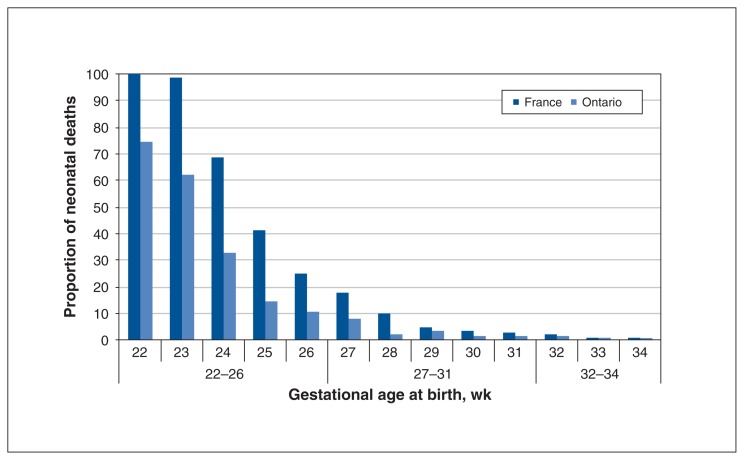

The most important difference between the cohorts in Ontario and France was the number of neonatal deaths as a proportion of live births. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of neonatal deaths per live birth at each gestational age in France and Ontario. The figure suggests that there was a higher proportion of neonatal deaths in France until 28 weeks gestation, after which the numbers became similar. Table 4 displays the crude and adjusted odds ratios for neonatal death in EPIPAGE-2 compared with BORN within 1 month and 5 months of birth. It should be noted that there was a slight discrepancy of 9 infants between the BORN database and data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information, probably because of differences in classification. The logistic regression was conducted with the data for infants in the BORN database. After we adjusted for intrinsic factors that were found to be different between the 2 groups and may have affected the rate of this outcome, there was a significantly higher rate of neonatal death in France than in Ontario from 22 weeks to 26 completed weeks gestation despite adjustment for intrinsic population differences (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.58; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13 to 5.89). This disparity became even more marked with further adjustment for management variations including rate of cesarean delivery, birth in a centre with a level 3 NICU and rate of corticosteroid use (adjusted OR 2.81; 95% CI 1.17 to 6.74). Most of the deaths appear to have occurred within the first month.

Figure 1:

Comparison of crude rates of neonatal death per live-born infants at each gestational age.

Table 4:

Logistic regression models showing the odds of neonatal death in France compared with Ontario

| Variable | No. of neonatal deaths | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Ontario | ||||

| Any neonatal deaths‡ | 702 | 356 | 1.47 (0.95 to 2.29) | 1.59 (0.91 to 2.78) | 1.87 (1.04 to 3.35) |

| Neonatal deaths within 1 mo‡ | 638 | 344 | 1.36 (0.87 to 2.14) | 1.46 (0.82 to 2.58) | 1.76 (0.97 to 3.21) |

| Neonatal deaths within 5 mo‡ | 696 | 356 | 1.46 (0.94 to 2.27) | 1.57 (0.90 to 2.74) | 1.84 (1.03 to 3.29) |

| Neonatal deaths for births between 22 and 26 wk gestation | 502 | 266 | 2.06 (1.10 to 3.85) | 2.58 (1.13 to 5.89) | 2.81 (1.17 to 6.74) |

| Neonatal deaths within 1 mo | 470 | 259 | 1.90 (1.01 to 3.58) | 2.37 (1.03 to 5.44) | 2.57 (1.06 to 6.22) |

| Neonatal deaths within 5 mo | 497 | 267 | 2.02 (1.08 to 3.78) | 2.52 (1.10 to 5.75) | 2.71 (1.13 to 6.51) |

| Neonatal deaths for births between 27 and 31 wk gestation | 187 | 56 | 2.48 (0.86 to 7.13) | 1.98 (0.59 to 6.62) | 2.27 (0.66 to 7.73) |

| Neonatal deaths within 1 mo | 157 | 53 | 2.18 (0.73 to 6.49) | 1.78 (0.51 to 6.24) | 2.12 (0.59 to 7.59) |

| Neonatal deaths within 5 mo | 186 | 56 | 2.46 (0.85 to 7.09) | 1.97 (0.59 to 6.59) | 2.25 (0.66 to 7.67) |

| Neonatal deaths for births between 32 and 34 wk gestation | 13 | 34 | 1.58 (0.39 to 6.46) | 1.47 (0.34 to 6.46) | 1.27 (0.28 to 5.71) |

| Neonatal deaths within 1 mo | 11 | 32 | 1.37 (0.32 to 5.84) | 1.30 (0.28 to 5.95) | 1.20 (0.26 to 5.64) |

| Neonatal deaths within 5 mo | 13 | 33 | 1.58 (0.39 to 6.46) | 1.47 (0.34 to 6.46) | 1.27 (0.28 to 5.71) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Models adjusted for maternal age, gestational hypertension, assisted reproductive therapy, infant birth weight and multifetal pregnancy.

Models additionally adjusted for cesarean delivery, antenatal steroid use and delivery in a hospital with level 3 care.

Regression models weighted to account for stratified sampling methodology used by EPIPAGE-2 in setting up the cohort in France.

To further verify neonatal mortality data we also compared our BORN Ontario cohort with the 2014 annual report of the Canadian Neonatal Network, which maintains a database of preterm infants admitted to level 3 centres across Canada.19 Although Ontario NICUs constitute a substantial proportion of the sites included in the Canadian Neonatal Network data, the data are collected separately from the BORN data.9 We also verified the EPIPAGE-2 numbers with the literature.20 This supported our findings that the crude survival rates in the French and Ontario cohorts do not become similar until 28 weeks gestation (Figure 1).

We performed further analysis by excluding the babies born at less than 24 weeks gestation. After adjustment for all of the same factors, the adjusted OR for neonatal death was 2.76 (95% CI 0.98 to 7.76). Although this suggests a trend toward higher mortality in France even when babies born at 22–23 weeks gestation were excluded, it was not statistically significant because of the loss of power from the reduction in sample size. There also appears to have been a higher rate of stillbirths in the French cohort.

Interpretation

The most interesting finding in this study is the higher number of neonatal deaths in France than in Ontario especially at the lower gestational ages despite adjustments for population and management differences. We also found statistically significant differences in certain maternal and neonatal baseline characteristics across all gestational ages, including mean maternal age and infant birth weight. In addition, there were some differences in the rates of gestational hypertension, use of assisted reproductive technology and multifetal pregnancy, with France having higher numbers. In addition, a greater percentage of deliveries occurred in centres with level 3 NICUs in France. There was also a higher rate of stillbirths in the French cohort.

Demographic differences such as maternal age are probably a reflection of intrinsic cultural and social differences between the populations. At the time of the 2 cohorts, France appears to have had better insurance coverage for patients seeking assisted reproductive technology treatments. The higher proportion of assisted reproductive technology use in France could explain the higher rates of multifetal pregnancies in that country. Both in vitro fertilization and multifetal pregnancies are associated with higher rates of pregnancy-related complications such as gestational hypertension.17,18 France probably had a higher number of deliveries in hospitals with a level 3 NICU because Ontario has nearly twice the land area of France and most of the level 3 NICUs are located in the southern part of the province. This large geographic area can make transport of labouring mothers to a level 3 NICU more challenging. Although the higher number of stillbirths in France could be related to less aggressive obstetrical management, it is difficult to speculate about the exact reason because not all stillbirths may be entered into the BORN database.

Previous studies have compared the morbidity and mortality of preterm infants in developed nations and found significant variations despite similar access to available technology and expertise.10,11,21 Helenius and colleagues recently compared the survival rates of 10 neonatal networks and found marked differences in mortality at lower gestational ages, with the difference diminishing as the gestational age increased.8 One possible explanation for the significant disparity in survival at lower gestational ages despite adjustments may be related to differing beliefs regarding the “survivability” of extreme preterm infants.22 In a previous publication using EPIPAGE-2 data, intensive care was withheld or withdrawn for more than 90% of live-born infants between 22 and 23 weeks gestation, 38% at 24 weeks, 8% at 25 weeks and 3% at 26 weeks.23 Although we do not have specific data for the Ontario cohort, the 2014 annual report of the Canadian Neonatal Network indicated that only 43.9% of babies born at 22–23 weeks received palliative care, 4.9% of babies born at 24 weeks, 1.2% at 25 weeks and 0.6% at 26 weeks.19 At the time of the cohorts, the general consensus in France was to not offer resuscitation for infants born at fewer than 24 weeks gestation. For the Ontario cohort, the Canadian Pediatric Society guideline recommended no resuscitation at fewer than 23 weeks and a discussion with the parents between 23 and 25 weeks.24,25 This may explain some of the differences in survival at the limits of viability. Nonetheless this would not explain the difference in mortality of babies born at more than 24 weeks gestation. Smith and colleagues evaluated whether the approach taken by care centres at 22–24 weeks is predictive of outcomes.26 They concluded that a physician’s willingness to provide care to extremely low gestation infants is associated with improved outcome. The marker they found to be most indicative of an intention to provide aggressive care is the use of antenatal steroids. However, in our results, there was no difference in the rate of antenatal steroid administration in the lowest gestational age group and higher steroid administration in France for the higher gestational ages. France also did better in delivering premature babies in a centre with a level 3 NICU. Thus, the EPIPAGE-2 cohort actually received more aggressive antenatal management on the basis of the variables we collected. It is possible that there was also a difference in the approach of clinicians to these infants on the basis of post-delivery assessment of the infant’s clinical status, with a lower threshold for transitioning to palliative care in France. This may have been reflected in our finding that most of the deaths occurred within the first month of life. In the original EPIPAGE-1 cohort, there was a higher probability of death after active withdrawal in France than in the United Kingdom.27 In a single-centre study published in 2005, it was found that more than 70% of newborn deaths in the centre were a result of withdrawal of care in cases deemed “futile.”28

Limitations

Through this study, we were able to compare the obstetrical management and survival of 2 very large cohorts of preterm infants born over similar time periods. Limitations include the retrospective nature of the comparison. There may also have been missing covariates that were not identified and adjusted for, such as aspects of postnatal management. In addition, we were unable to compare data for infants born at the same time on the same day and we did not have data on cause of death, which could have provided further insight into approaches to decision-making. Furthermore, we did not compare the management of infants during their NICU stay, nor did we compare major morbidities and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. However, recent publications from EPIPAGE-2 and the Canadian Neonatal Follow-up Network do not appear to suggest that neurodevelopmental outcomes were worse in the Canadian cohort.29,30 Lastly, we are unable to comment on the difference in stillbirth rates between France and Ontario.

Conclusion

Even after we controlled for prognostic factors and differences in obstetrical management, there appeared to be a significant difference in the survival of infants born at 26 weeks gestation or earlier in France and Ontario, with a greater proportion of live-born infants surviving in Ontario. Although we speculate that the difference in mortality may be related to ethical decision-making, there could also be significant variation in the postnatal management of these preterm infants, which will need to be explored further. Further work will need to be done to explore the long-term outcomes of surviving infants and the reason for the difference in survival given that France and Ontario have access to similar technologies. The difference in stillbirth rates can also be explored.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Dianna Wang, Abdool Yasseen III, Laetitia Marchand-Martin, François Goffinet, Mark Walker, Pierre-Yves Ancel and Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil designed the study. Abdool Yasseen III, Laetitia Marchand-Martin, Ann Sprague and Pierre-Yves Ancel analyzed the data. Dianna Wang and Abdool Yasseen III wrote the manuscript and all other authors revised it for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Funding was provided by a joint partnership between the University of Ottawa and Paris Descartes University.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/1/E159/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondel B, Coulm B, Bonnet C, et al. Trends in perinatal health in metropolitan France from 1995 to 2016: results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46:701–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies) BMJ. 2012;345:e7976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EXPRESS Group. Fellman V, Hellström-Westas L, Norman M, et al. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA. 2009;301:2225–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeitlin J, Ancel P-Y, Delmas D, et al. EPIPAGE and MOSAIC Ile-de-France Groups. Changes in care and outcome of very preterm babies in the Parisian region between 1998 and 2003. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95:F188–93. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.156745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field DJ, Dorling JS, Manktelow BN, et al. Survival of extremely premature babies in a geographically defined population: prospective cohort study of 1994–9 compared with 2000–5. BMJ. 2008;336:1221–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39555.670718.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Draper ES, Zeitlin J, Fenton AC, et al. MOSAIC research group. Investigating the variations in survival rates for very preterm infants in 10 European regions: the MOSAIC birth cohort. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F158–63. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.141531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helenius K, Sjörs G, Shah PS, et al. International Network for Evaluating Outcomes (iNeo) of Neonates. Survival in very preterm infants: an international comparison of 10 national neonatal networks. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171264. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provincical and territorial ranking: income per capita. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada; [accessed 2019 Feb 14]. Available: www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/provincial/economy/income-per-capita.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su BH, Hsieh WS, Hsu CH, et al. Premature Baby Foundation of Taiwan (PBFT) Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from Taiwan: comparison with Canada, Japan, and the USA. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isayama T, Lee SK, Mori R, et al. Comparison of mortality and morbidity of very low birth weight infants between Canada and Japan. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e957–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BORN Ontario [main page] Ottawa: [accessed 2014 Dec 30]. Available: https://www.bornontario.ca/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemyre B, Moore G. Counselling and management for anticipated extremely preterm birth. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22:334–41. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larroque B, Bréart G, Kaminski M, et al. Survival of very preterm infants: EPIPAGE, a population based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F139–44. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.020396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent AL, Wright IMR, Abdel-Latif ME New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory Neonatal Intensive Care Units Audit Group. Mortality and adverse neurologic outcomes are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:124–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibai BM, Hauth J, Caritis S, et al. Hypertensive disorders in twin versus singleton gestations. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:938–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opdahl S, Henningsen AA, Tiitinen A, et al. Risk of hypertensive disorders in pregnancies following assisted reproductive technology: a cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1724–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah P, Yoon EW, Chan P. The Canadian Neonatal Network annual report 2014. Toronto: Canadian Neonatal Network; 2015. [accessed 2016 Aug 30]. Available: www.canadianneonatalnetwork.org/Portal/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=eGgxmMubxjk%3D&tabid=39. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ancel P-Y, Goffinet F, Kuhn P, et al. EPIPAGE-2 Writing Group. Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:230–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah PS, Lui K, Sjörs G, et al. International Network for Evaluating Outcomes (iNeo) of Neonates. Neonatal outcomes of very low birth weight and very preterm neonates: an international comparison. J Pediatr. 2016;177:144–52.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher K, Aladangady N, Marlow N. The attitudes of neonatologists towards extremely preterm infants: a Q methodological study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016;101:F31–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-308071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perlbarg J, Ancel PY, Khoshnood B, et al. EPIPAGE-2 Ethics group. Delivery room management of extremely preterm infants: the EPIPAGE-2 study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016;101:F384–90. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferies AL, Kirpalani HM Canadian Paediatric Society Fetus and Newborn Committee. Counselling and management for anticipated extremely preterm birth. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:443–6. doi: 10.1093/pch/17.8.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriette G, Rameix S, Azria E, et al. Groupe de réflexion sur les aspects éthiques de la périnatologie. Very premature births: dilemmas and management. Second part: Ethical aspects and recommendations [article in French] Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith PB, Ambalavanan N, Li L, et al. Generic Database Subcommittee; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Approach to infants born at 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation: relationship to outcomes of more-mature infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1508–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pignotti MS, Berni R. Extremely preterm births: end-of-life decisions in European countries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95:F273–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.168294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton L, Hodgman JE. The contribution of withholding or withdrawing care to newborn mortality. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1487–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Synnes A, Luu TM, Moddemann D, et al. Canadian Neonatal Network and the Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network. Determinants of developmental outcomes in a very preterm Canadian cohort. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102:F235–4. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C, et al. EPIPAGE-2 writing group. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.