Abstract

Objectives.

The purpose of this paper is to report on the Center of Excellence for Research on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CERC) at RAND. The overall project examined the appropriateness of chiropractic spinal manipulation and mobilization (M/M) for chronic low back pain (CLBP) and chronic cervical pain (CCP), using the RAND/UCLA (RUAM) method for Appropriateness but also including patient preferences and costs to acknowledge the importance of patient centered care in clinical decision making.

Methods.

This article is a narrative summary of the overall project and its inter-related components (ie, 4 Research Project Grants (RO1s) and 2 centers), including the Data Collection Core whose activities and learnings will be the subject of a following series of methods papers.

Results.

The project team faced many challenges in accomplishing data collection goals. The processes we developed to overcome barriers may be of use to other researchers and for practitioners who may want to participate in such studies in Complementary and Integrative Health (ClH), which is previously known as Complementary and Alternative Medicine or “CAM.”

Conclusions

This large, complex, and successful project gathered online survey data, collected charts, and abstracted chart data from thousands of chiropractic patients. This article delineates the challenges and lessons that were learned during this project so that others may gain from our experience. This information may be of use to future research that collects data from independent practitioners and their patients as it provides what is needed to be successful in such studies and may encourage participation.

Keywords: Manipulation, Spinal; Chronic pain; Low back pain; Neck pain; Chiropractic; Complementary Therapies

INTRODUCTION

Although there is general agreement that all patients should receive health care that is appropriate to their health problem and that inappropriate care is costly,1 the challenge comes in determining what is appropriate care.2 In general, appropriateness comprises the right therapy, for the right problem, and for the right patient.

In the current health care system, one answer to the question of appropriateness is that evidence-based care is appropriate care. However, that only shifts the problem from deciding what is appropriate to deciding what is evidence-based. Further, there is considerable debate about what percentage of treatments can claim to be evidence-based. Some estimate that as little as 15%- 20% of all medical practice can truly claim to be evidence-based.3–6 Hicks notes, “It is generally accepted that between 20–60% of patients either receive inappropriate care or are not offered appropriate care.” 6 For large areas of health care, including complementary and integrative health (CIH), (previously known as Complementary and Alternative Medicine or “CAM”) 7[8], we have very little data on how much care is appropriate or evidence-based.

In the 1980s the RAND Corporation 2, 8–13 and UCLA pioneered a method to study the appropriateness of care that takes advantage of the available evidence base, but also draws upon the clinical acumen and experience of practitioners.14 This approach uses a mixed expert and clinician-based panel to consider the available evidence and to then judge for a particular treatment, whether

“for an average group of patients presenting with this set of clinical indications to an average US physician, the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the procedure is worth doing … excluding considerations of monetary cost.” 12

This has been the most widely used and studied method for defining and identifying appropriate care in the US, and it has also been used internationally.15–17 The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method (RUAM) makes it feasible to take the best of what is known from research and apply it—using the expertise of experienced clinicians—over the wide range of patients and presentations seen in real-world clinical practice. Clinicians are, after all, the final translators of evidence into practice, and this approach formalizes the process. 18–25

However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), appropriate care is about ensuring that individuals receive care that is (a) clinically effective, (b) cost-effective, and consistent with (c) ethical principles, and (d) preferences relevant to individuals, communities and society.2, 9 This represents a paradigm shift from previous, narrower definitions of appropriateness which only considered effectiveness, efficacy and safety. This broader WHO perspective makes explicit that the appropriateness of a procedure: (a) can be examined at multiple levels (e.g., society, community, individual); and (b) is, in part, dependent on the needs, desires, attitudes, expectations and preferences of the patients who receive the procedure.

We argue that this broader definition is especially critical for determining the appropriateness of Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH) treatments, primarily because CIH users are atypical healthcare users in several important ways. For example, much of CIH is paid for by the patient out-of-pocket. It is estimated that CIH utilization amounts to out-of-pocket costs for patients of about $27 billion annually. 10 In addition, the majority of CIH use is consumer-driven, with patients acting as the primary locus of health care integration. 11 But while patients are known to play an important role in driving the expanded use of CIH, little is known about how patients make CIH-related decisions, what their preferences are for types of treatments or what kinds of results they are seeking and would be satisfied with. If appropriateness of care is ultimately about matching clinically effective and cost-effective treatments with the physical, mental and emotional needs of individuals who are suffering, then a more thorough understanding of patient-centered desires, expectations, attitudes and preferences, as well as the cost of these therapies, is required to make healthcare more effective and more efficient. This study was intended as a step in this direction.

The problem therefore for providers, patients, and policy makers is how do you decide what is or is not appropriate care. For researchers, it is how do you measure appropriateness, how much of health care is appropriate, what effect patient preferences and costs have on appropriateness, and what effect does appropriate care have on outcomes.

In 2013, RAND was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health to advance the methodology of determining the appropriateness of care in CIH. The target treatments and exemplars for CIH were spinal manipulation and mobilization (M/M) and the target conditions were chronic low back pain (CLBP) and chronic cervical pain (CCP). One important component of this project was the collection of a large amount of data from doctors of chiropractic and their patients.

In this series of articles in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, we describe how we gathered the varied and detailed data required to achieve our study objectives of measuring the appropriateness of M/M for CLBP and CCP, and determining whether patient preferences and costs affect appropriateness, and whether appropriateness effects outcomes. In each paper, we outline the problems we faced with each step of the data collection effort and the methods developed to overcome those problems. By doing so, we provide a blueprint that can be used by others who wish to study the care provided by various types of practitioners in private practice, including those offering CIH. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the overall project and its several parts.

THE RAND CENTER OF EXCELLENCE FOR RESEARCH INTO CIH (CERC)

In 2013, RAND was funded by NCCIH through a cooperative agreement to establish CERC to advance the methodology of researching appropriateness in CIH. In this era of rising health care costs, it is increasingly urgent to evaluate the appropriateness of therapies provided to Americans. While investigating the appropriateness of CIH therapies is important enough, the point has been reached where such evaluations must also include considerations of outcomes, patient preferences, and cost-effectiveness so that the overall value of these treatments, to patients, providers and society, can be determined.

In addition to the expanded view of appropriateness, this project was innovative in other ways. First, there has only been one previous study published on the appropriateness of CIH care. RAND previously applied the RUAM to M/M for acute low back pain 23, 26, 27 and had conducted a literature review and expert panel previously for M/M 28, 29 for cervical manipulation. Those studies demonstrated the feasibility of applying appropriateness methods to CIH, and CERC was intended to develop the methods further and make these types of studies possible in a broader selection of CIH for a variety of conditions.

In addition, this study examined whether the PROMIS health-related quality of life measure(s) are adequately sensitive in CIH populations and adapted Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) measures to chiropractic.

Organization of CERC

The CERC study contained four R01-sized projects:

Project 1: Clinician-Based Appropriateness

Project 2: Outcomes-Based Appropriateness

Project 3: Patient Preference-Based Appropriateness

Project 4: Resource Utilization-Based Appropriateness

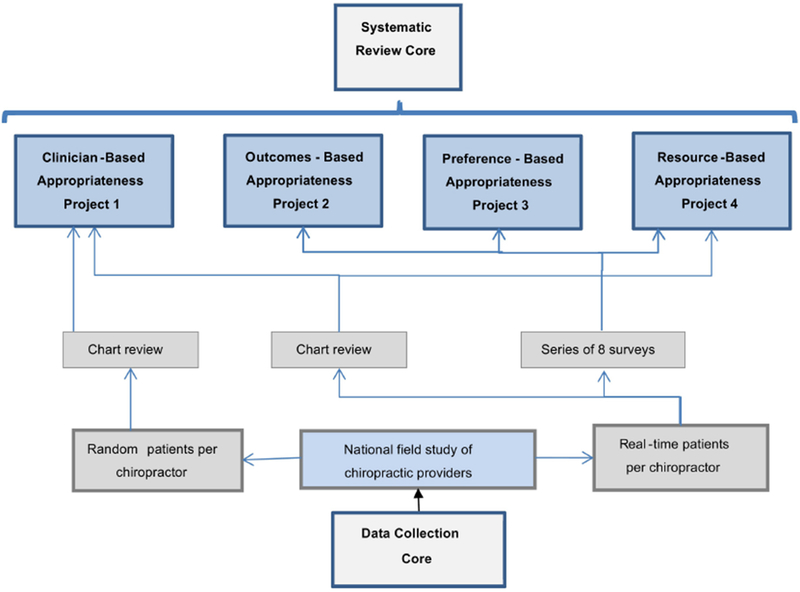

In addition to the four projects, CERC had two core centers, one for conducting systematic reviews (the Systematic Review Core) and one integrated data collection center (the Data Collection Core) to collect the data required by all four projects (Figure 1). The center involved a collaboration between RAND, UCLA and the Samueli Institute but was located and administrated at RAND.

Figure 1.

The work of the Data Collection Core (DCC) is the focus of this series of methods papers. Below we briefly introduce the Systematic Review Core (SRC) and what it provided to the four projects. Then we will introduce the four projects and note where each requires the data collected by the DCC. Finally, we will provide more detail on the DCC, including its components which will be explained more fully in the paper series.

Systematic Review Core

An extensive review of the literature on M/M for CLBP and CCP was done and two systematic reviews prepared (including meta-analyses) with the support of the Systematic Review Core (SRC). The systematic review for CLBP has been published 30 and the review for CCP has been submitted for publication.

From these reviews and from sets of indications previously used in RAND’s study of acute low back and cervical pain, a set of clinical scenarios for performing M/M for CLBP and CCP was developed for Project 1, Clinician-Based Appropriateness. These clinical scenarios categorize patients in terms of their symptoms, past medical history, and the results of previous diagnostic tests. In the RUAM, the expert and clinician-based panels rate M/M for CLBP and CCP for each of these indications. In their ratings, these panelists utilize the results of the systematic reviews the SRC generated. The SRC also produced literature reviews of the evidence for patient reported outcomes (for Project 2: Outcomes-Based Appropriateness), patient preferences (for Project 3: Patient Preferences Appropriateness), and the costs of M/M (for Project 4: Resource Utilization-Based Appropriateness).

Project 1: Clinician-Based Appropriateness

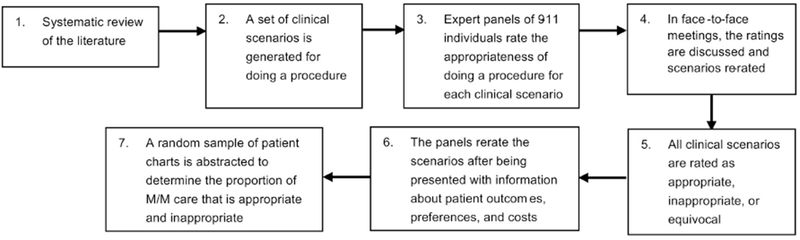

Once the clinical scenarios were created, two multidisciplinary panels of nine to eleven clinical and research experts each initially received the literature synthesis (systematic reviews and meta-analyses from the SRC) and the set of clinical scenarios. Based on the literature and their own clinical experience where applicable, panelists were asked to rate at home and on their own the appropriateness of M/M for each patient type (clinical scenario) for CLBP (chronic low back pain panel) or for CCP (chronic cervical pain panel). The panels were then brought together in a face-to-face meeting and the results of the ratings shared with the panel members. Following group discussions, the panels re-rated the indications. Once the ratings of appropriateness were determined for each indication, the charts of a random sample of patients being treated with M/M (by chiropractors) for CLBP and CCP were reviewed to determine the proportion of M/M given that was appropriate. Later in the project, in two further rounds of ratings, the panels were asked to rerate the clinical scenarios at home and then face-to-face to ascertain if they had changed their ratings based on presented data from Projects 2, 3 and 4 on patient outcomes, preferences and cost. Figure 2 outlines the process used to derive ratings of appropriateness/inappropriateness.

Figure 2.

Project 2: Outcomes-Based Appropriateness

Project 2 will examine the applicability of standardized patient reported outcomes that assess patient experiences of care (Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems or CAHPS®) and health-related quality of life (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement and Information System or PROMIS®) to chiropractic patients who have experienced M/M for CCP or CLBP, and to make modifications to these measures where needed. Testing involved focus groups, cognitive interviews, pilot tests, and then fielding of the measures to our national sample. This project will also use data from the chart reviews to determine whether the appropriateness of M/M received affects patients’ experiences of care and health-related quality of life outcomes.

Project 3: Patient Preference-Based Appropriateness

Given the prevalence of patient self-referral and the health system-wide focus on patient-centered care, this project examined how patient preferences affect what is considered appropriate care. Objectives for this study included understanding how CLBP and CCP patients decide to use M/M and determining what they believe is appropriate care, drawing on data from our national sample to determine patient preferences for M/M care.

Project 4: Resource Utilization-Based Appropriateness

Project 4 had two components. The first was to provide information to the panels regarding the relative costs of M/M compared to the other therapies available for CLBP and CCP. These data were used by the panel to determine whether the relative cost or cost-effectiveness of M/M compared to alternatives had an effect on panelists’ ratings of appropriateness. The data on relative costs and cost-effectiveness came from two simulation models built on the results of studies of different nonsurgical interventions for CLBP and CCP.

The second component of Project 4 was to examine whether economics could provide any information as to the appropriate duration of M/M care once it was chosen. This analysis was built on biweekly symptom and healthcare resource use data gathered by the DCC.

Data Collection Core

The Data Collection Core (DCC) gathered all the data required by the four CERC projects. As discussed above, these data involved abstractions from patient charts as well as nationwide surveys of patients who were being treated by M/M for their CLBP and/or CCP in terms of their characteristics and outcomes collected from patients.

Doctors of chiropractic associated with 125 practices/clinics were recruited from 6 sites geographically distributed across the US: Portland, Oregon; San Diego, California; Dallas, Texas; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Tampa, Florida; and Seneca Falls, New York. While the recruitment and data collection in the practices will be described fully in one of the series papers, a short account will be given here. A detailed description of the patient sample has been published.31

Online survey data collection.

From each practice, we recruited patients over a four-week window and asked those who had CLBP and/or CCP to participate. Once patients consented and we confirmed the chronicity of their pain, we interacted with them via weblinks to online surveys over 3 months, during which they completed a total of up to 8 surveys. At baseline, we enrolled 2024 patients of which 1835 completed the final 3-month follow up survey. We asked each patient who was enrolled for permission to also scan their patient file/chart, which yielded 1708 files.

The longer surveys were fielded during screening, at baseline, and at 3-months. Shorter biweekly surveys between baseline and 3 months only included healthcare utilization, pain and function so as to minimize patient burden and maximize response rates.

Each practitioner also completed a survey that captured demographic data (age, gender, race, marital status, chiropractic school attended, etc.) and asked about their practice, their patients—e.g., number of years in practice, number of years at present location, arrangements of practice (solo, group, multi-specialty), practice management techniques, practice gross and net income in the last year, insurance coverage, services offered, referral patterns for diagnostic studies, and treatment procedures used.

Collection and abstraction of data from charts

We also selected a random set of files of chronic patients from the practices. This was done to generate a sample of patients that was as representative as possible of all chiropractic patients. This representative retrospective sample allowed us to calculate the amount of appropriate and inappropriate care being offered to chiropractic patients and the proportion of patients being treated who have chronic pain. However, this retrospective sample also as a method to determine the representativeness of the sample of patients who participated the surveys to determine if the recruited sample was biased in any way. These scanned files (both the patients in the study and the random sample) were then protected in encrypted files and transferred to RAND where we abstracted the data and de-identified the files. The chart abstraction was done by 4 doctors of chiropractic. The project was approved by the Human Subjects Protection Committee (HSPC) at RAND.

Discussion

This overview of the CERC study attests to the complexity of measuring the appropriateness of CIH care and its potential modifications even with an established CIH profession such as chiropractic. To steal a political term, it takes a village to do this work. Sixteen research staff were employed on this project and the total budget for the project was over $8 million.

We learned a lot in this project and in future papers in JMPT we will elaborate on how we were able to bring the data collection portion of this project to fruition. There were many moving parts that needed to be coordinated and integrated, the parts were highly symbiotic, and each element was required to be able to capture the data needed to answer the question of whether and under what circumstances is manipulation/mobilization appropriate for the treatment of chronic low back and neck pain.

The lessons learnt here may provide a basis for others who follow particularly when combined with the detailed information of what we did to achieve our results in following papers in this series. But the lessons are not just for researchers, we hope that they will highlight the extraordinary contribution made by the practice doctors of chiropractic and their staff in this process and encourage future participation. It is only through participation in studies like this that the chiropractic research agenda can be advanced and only with that can chiropractic fully participate in the world of evidenced-based practice.

Limitations

This study was done in 6 states of one country (US), thus there is some regional limitation. It also was done in clinics whose practitioners agreed to participate and with patients who agreed to participate. This is acceptable in a Center that was funded as a methods center where we are not trying to generalize but are trying to see if this type of research method can be conducted in practices. It is also limited by focusing on chiropractic. Most chiropractic clinics have an organizational structure that includes such things as organized filing systems including electronic files, computers, scanning equipment. Although we provided some of this when necessary but for the most part it was possible to work in the clinics with the infrastructure with limited disruption. It may be the case that less established CIH/CAM professions may not have the infrastructures to allow for this. That will need to be discovered in future research.

Conclusion

This article delineates the challenges and lessons that were learned during this project. This information may be of use to future research that collects data from independent practitioners and their patients as it provides what is needed to be successful in such studies and may encourage participation. There are three major conclusions from this report:

Appropriateness studies based on practices can be done in chiropractic and probably other CIH/CAM practices

Doctors of chiropractic and their staff are not only willing to participate, but will happily assist in collecting the data and recruiting the patients. They can be trained to participate in quite sophisticated data collection and data protection methods.

Where patients feel the clinic is supportive they are highly receptive to participating and once enrolled tend to stick with the project.

In following articles of this series, we will provide detailed information on: HIPAA Requirements; Survey Design; Building a Practice Based Network; Provider- and Patient-Centered Research; and Chart Selection and Abstraction.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Grant No: 1U19AT007912-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors report that they were funded by a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health during the study.

Contributor Information

Ian D Coulter, RAND Corporation, UCLA, Southern California Health Sciences, Santa Monica, California, USA

Patricia M Herman, RAND Corporation, Health, Santa Monica, California, USA

Gery W Ryan, RAND Corporation, Health, Santa Monica, California, USA

Ronald D Hays, Division of General Internal Medicine & Health Services Research, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Westwood, Los Angeles

Lara G Hilton, RAND Corporation, Health, Santa Monica, California, USA

Margaret D Whitley, RAND Corporation, Health, Santa Monica, California, USA

References

- 1.Berwick D and Hackbarth A. Eliminating Waste in US Health Care. JAMA 2012; 307: 1513–1516. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2012.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter I, Elfenbaum P, Jain S, et al. SEaRCH™ expert panel process: streamlining the link between evidence and practice. BMC Research Notes 2016; 9: 16 DOI: 10.1186/s13104-015-1802-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Congress OoTA. Assessing the efficacy and safety of medical technologies. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaud G, McGowan J, van der Jagt R, et al. Are therapeutic decisions supported by evidence from health care research? Archives of internal medicine 1998; 158: 1665–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imrie R and Ramey D. The evidence for evidence-based medicine. Complementary Therapies in Med 2000; 8: 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks N Some observations on attempts to measure appropriateness of care. Br Med J 1994; 309: 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter I Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Promises and Problems. Complementary Medicine Research 2007; 14: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter I and Admas A. Consensus Methods, Clinical Guidelines, and the RAND Study of Chiropractic. Am Chiro Assoc J of Chiropractic 1992; December: 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulter I Evidenced-based Practice and Appropriateness of Care Studies. Journal of Evidence- Based Dental Practice 2001; 1: 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulter I Expert panels and evidence: The RAND alternative. Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice 2001; 1: 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter I, Shekelle P, Mootz R, et al. The use of Expert Panel Results: The RAND Panel for Appropriateness of Manipulation and Mobilization of the Cervical Spine. Topics in Clinical Chiropractic 1995; 2(3): 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shekelle P The Appropriateness Method. Medical Decision Making 2004; 24: 228–231. DOI: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook R, Chassin M, Fink A, et al. A Method for the Detailed Assessment of the Appropriateness of Medical Technologies. Int J Techol Assess Health Care 1986; 2: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreasen P Consensus Conferences in Different Countries. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 1988; 4: 305–308. DOI: 10.1017/S0266462300004104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stocking B First Consensus Development Conference in the United Kingdom: On Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. British Medical Journal 1985; 291: 713–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casparie A, Klazinga N, van Everdingen J, et al. Health-Care Providers Resolve Clinical Controversies: The Dutch Consensus Approach. Austrailian Clinical Review 1987: 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClellan M and Brook R. Appropriateness of Care: A Comparison of Global and Outcome Methods to Set Standards. Medical care 1992; 30: 565–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekelle P, Adams A, Chassin M, et al. The Appropriateness of Spinal Manipulation for Low-Back Pain: Indications and Ratings by a Multidisciplinary Expert Panel. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fink A, Brook R, Kosecoff J, et al. Sufficiency of Clinical Literature on the Appropriate Uses of Six Medical and Surgical Procedures. Western Journal of Medicine 1987; 147: 609–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chassin M How do we decide whether an investigation or procedure is appropriate? Anthony Hopkins ed. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leape L, Park R, Kahan J, et al. Group judgments of appropriateness: The effect of panel composition. Quality Assurance in Health Care 1992; 4: 151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn KL, Park RE, Vennes J, et al. Assigning Appropriateness Ratings for Diagnostic Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Using Two Different Approaches. Medical care 1992; 30: 1016–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekelle P, Adams A, Chassin M, et al. The Appropriateness of Spinal Manipulation of Low-Back Pain: Indications and Ratings by an all Chirporactic Expert Panel. Report no. 4025/3-CCR/FCER; 1992, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shekelle P, Kahan J, Bernstein S, et al. The Reproducibility of a Method to Identify the Overuse and Underuse of Medical Procedures. New England Journal of Medicine 1998; 338: 1888–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coulter I, Adams A and Shekelle P. Impact of varying panel membership on ratings of appropriateness in consensus panels: A comparison of a multi- and single disciplinary panel. 1995, p.577–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shekelle P, Hurwitz E, Coulter I, et al. The Appropriateness of Chiropractic Spinal Maniuplation for Low Back Pain: A Pilot Study. Manipulative Physiological Therapy 1995; 18: 265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shekelle P, Coulter I, Hurwitz E, et al. Congruence between decisions to initiate chiropractic spinal manipulation for low back pain and appropriateness criteria in North America. Annals of Internal Medicine 1998; 129: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coulter I, Hurwitz E, Adams A, et al. The Appropriateness of Manipulation and Mobilization of the Cervical Spine. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coulter I Manipulation and Mobilization of the Cervical Spine: The Results of a Literature Survey and Consensus Panel. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 1996; 4: 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulter I, Crawford C, Hurwitz E, et al. Manipulation and mobilization for treating chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Spine Journal 2018: 1529–9430. DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herman P, Kommareddi M, Sorbero M, et al. Characteristics of Chiropractic Patients Being Treated for Chronic Low Back and Chronic Neck Pain. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]