Abstract

Purpose:

Long-term disease-free survival patterns following surgical, radiation, and endocrine therapy treatments for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) are not well characterized in general US practice.

Methods:

We identified 1,252 women diagnosed with DCIS in Vermont during 1994–2012 using data from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System, a statewide registry of breast imaging and pathology records. Poisson regression and Cox regression with time-varying hazards were used to evaluate disease-free survival among self-selected treatment groups.

Results:

With 7.8 years median follow-up, 192 cases experienced a second breast cancer diagnosis. For women treated with breast conserving surgery (BCS) alone, the annual rate of second events decreased from 3.1% (95% CI: 2.2–4.2%) during follow-up years 1–5 to 1.7% (95% CI: 0.7–3.5%) after 10 years. In contrast, the annual rate of second events among women treated with BCS plus adjuvant radiation therapy increased from 1.8% (95% CI: 1.1–2.6%) during years 1–5 to 2.8% (95% CI: 1.6–4.7%) after 10 years (P<0.05 for difference in trend compared to BCS alone). Annual rates of second events also increased over time among women treated with BCS plus adjuvant radiation and endocrine therapy (P=0.01 for difference in trend compared to BCS alone). The rate of contralateral events increased after 10 years for all groups with adjuvant treatments. The rate of second events did not vary over time among women who underwent ipsilateral mastectomy (P=0.62).

Conclusions:

Long-term risk of a second event after DCIS varies over time in a manner dependent on initial treatment.

Keywords: breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ, treatment outcome, cohort studies, disease-free survival

Approximately 20% of breast cancers diagnosed in the United States are ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a non-invasive form of breast cancer [1]. There are several treatment approaches for DCIS, including combinations of surgical management and adjuvant therapies [2]. While no studies have demonstrated mortality differences between treatments, observational studies have demonstrated lower risk of recurrence with mastectomy compared to breast conserving surgery (BCS) alone [3–5] and randomized trials have demonstrated that adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) or endocrine therapy (ET) after BCS reduces risk of recurrence [6–8].

Outside of clinical trials, treatments are guided by patient preferences and values related to side effects and perceptions of protection against recurrence, in addition to DCIS characteristics including grade, size, and estrogen receptor (ER) status [2,9–11]. Uncertainty remains regarding long-term outcomes following each DCIS management strategy as it is used in general US practice. In particular, long-term data on rates of ipsilateral and contralateral events, type of recurrence (DCIS vs. invasive breast cancer), and timing of recurrence from population-based cohorts are limited. There is particular uncertainty regarding the long-term duration of effectiveness for both RT and ET, with some studies suggesting that RT reduces risk of recurrence only within the first 5 years after treatment [12,13].

We sought to provide evidence regarding long-term DCIS outcomes among a population-based cohort of women diagnosed in the state of Vermont. Women in our observational study self-selected into treatment groups and thus there are inherent biases when attempting to compare the effectiveness of one treatment group to another. Instead, we sought to characterize patterns in disease-free survival within each treatment group. In particular, we describe how risk of second events changed during the course of long-term follow-up.

METHODS

Study setting

We constructed an observational cohort of women diagnosed with DCIS in Vermont during 1994–2012 using data from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System (VBCSS), a registry of breast cancer screening and diagnostic imaging performed at radiology facilities in Vermont [14] and a founding member of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium [15]. The VBCSS links patient and breast imaging data from radiology facilities to statewide breast pathology records and Vermont Cancer Registry (VCR) data. This study was approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent and all study procedures were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Study population

Women aged 18 years and older diagnosed with DCIS as a first primary breast cancer in the VBCSS with at least 6 months of follow-up were eligible for inclusion in the cohort. Women with a previous breast cancer diagnosis or a concurrent invasive breast cancer diagnosis (within 6 months of DCIS diagnosis) and those who opted out of participation in VBCSS research (10% of women) were excluded. A total of 1,376 potentially eligible DCIS cases were identified. Pathology slides and/or blocks were available for 1,154 cases and a centralized review was conducted by four breast pathology experts. The DCIS diagnosis was confirmed in 95.7% of cases (38 cases were downgraded to benign disease; 12 cases were upgraded to invasive disease); the 38 downgraded cases were excluded, leaving 1,326 DCIS cases in the study cohort. For statistical analyses we excluded bilateral DCIS (N=5), cases with missing treatment data (N=49) and cases treated by bilateral mastectomy (N=20), leaving a final sample size of 1,252 DCIS cases.

Available data

Women undergoing breast imaging at radiology facilities in the state of Vermont are asked to complete a clinical questionnaire at each visit that collects data on demographics, height, weight, family history of breast cancer, reproductive/menstrual characteristics, and use of postmenopausal hormones. Women also report whether they have previously undergone needle biopsy, excisional biopsy, lumpectomy, mastectomy, or RT on each breast, and whether they have ever used ET (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors).

Radiology facilities provided data on all breast imaging exams, including indication for exam (i.e., screening vs. diagnostic) and assessment category. Assessments were classified as positive or negative according to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [16].

The VBCSS obtains copies of pathology reports for all breast specimens evaluated at pathology facilities in Vermont. A trained abstractor recorded standardized data on all malignant and benign diagnoses, including specimen type (e.g., core needle biopsy, lumpectomy, mastectomy), histology, grade, size, and results of hormone receptor testing. The VCR provided consolidated breast cancer diagnosis data to the VBCSS, including date of diagnosis, histological subtype, stage at diagnosis, hormone receptor status, and treatment information.

Measures and definitions

Treatment.

Type of surgery was defined as BCS, ipsilateral mastectomy, or bilateral mastectomy based on VCR data, pathology records, and clinical questionnaires. If disagreements between sources could not be resolved surgery type was set to unknown. Women who met either of the following criteria were considered to have received RT: 1) VCR indicated receipt of RT; or 2) self-reported RT on a clinical questionnaire after the date of DCIS diagnosis but before any recurrence. The same algorithm was used to define receipt of ET based on self-report and VCR data.

Second events.

Data from pathology reports and VCR records were used to identify second breast cancer diagnoses occurring at least 6 months after the index DCIS diagnosis. Second events were categorized as ipsilateral or contralateral relative to the index diagnosis and classified as either invasive breast cancer or DCIS.

Covariates.

Tumor characteristics for the index DCIS diagnosis, including grade, size, and ER status, were determined from VCR records and pathology records. Mode of detection was considered screening if the index DCIS was diagnosed within one year following a positive screening exam; symptom-detected if diagnosed within 6 months of diagnostic imaging in the absence of a recent positive screening exam; and missing if no breast imaging records were available within 6 months prior to the date of diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

Differences in the characteristics of women undergoing different treatments was assessed with Chi-square tests, using the method described by Fleiss to adjust for multiple pair-wise comparisons [17]. Follow-up time began at the date of diagnosis and continued until the earliest of: 1) a new breast cancer diagnosis or 2) the last VBCSS clinical questionnaire, radiology record, or pathology record. Patients were considered censored at the date of the last VBCSS record as they may have left the VBCSS catchment area. For certain analyses follow-up time was categorized as 0 to 5 years, more than 5 to 10 years, and more than 10 years. Incidence of second breast cancer for differing time intervals during follow-up was computed by dividing the number of events by the number of person-years occurring during that time period and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were based on the Poisson distribution. Poisson regression was used to compare differences in incidence between groups of women receiving different treatments and across time within treatment group. Differences in temporal patterns of risk during follow-up among treatment groups were assessed by including an interaction term in the Poisson regression model. Cumulative risk was estimated by fitting Cox regression models with time-varying hazard ratios. For BCS treatment groups, Cox regression with competing risks and time-varying hazard ratios was used to estimate probabilities of differing types of second events (ipsilateral invasive, ipsilateral DCIS and contralateral) during differing periods of follow-up. Women undergoing mastectomy were not included in the competing risk analysis because the nature of their treatment and the lack of surveillance mammography on the ipsilateral side resulted in few ipsilateral invasive events and no ipsilateral DCIS events. All analyses were performed in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among the cohort of 1252 DCIS cases, 1051 (83.9%) underwent BCS and 201 (16.1%) underwent mastectomy. As expected, type of treatment was related to the year of DCIS diagnosis; as adjuvant ET became available, fewer women underwent mastectomy or BCS alone (Table 1). Women who underwent mastectomy were more likely to have DCIS that was high grade, larger size, and ER negative compared to women who underwent BCS (either with or without adjuvant therapy; P<0.05). Among women undergoing BCS, women who underwent adjuvant RT (with or without adjuvant ET) were more likely to have higher grade and larger DCIS than women in the groups that did not receive radiation. Nearly all women who received adjuvant ET and a large majority (88.5%) of the women who underwent BCS alone had ER positive DCIS. A significantly smaller proportion (65.6%) of women who underwent adjuvant RT without ET had ER positive DCIS.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1,252 DCIS cases from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

|

All (N=1252) |

Mastectomy (N=201) |

BCS alone (N=327) |

BCS + RT (N=318) |

BCS + RT and ET (N=276) |

BCS + ET (N=130) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| <40 | 27 | 2.2 | 7 | 3.5 | 7 | 2.1 | 5 | 1.6 | 8 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 40–49 | 300 | 24.0 | 53 | 26.4 | 78 | 23.8 | 73 | 23.0 | 72 | 26.1 | 24 | 18.5 |

| 50–59 | 379 | 30.3 | 48 | 23.9 | 79 | 24.2 | 104 | 32.7 | 107 | 38.8 | 41 | 31.5 |

| 60–69 | 277 | 22.1 | 53 | 26.4 | 52 | 15.9 | 82 | 25.8 | 56 | 20.3 | 34 | 26.2 |

| 70–79 | 194 | 15.5 | 35 | 17.4 | 62 | 19.0 | 42 | 13.2 | 30 | 10.9 | 25 | 19.2 |

| 80+ | 75 | 6.0 | 5 | 2.5 | 49 | 15.0 | 12 | 3.8 | 3 | 1.1 | 6 | 4.6 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 1994–1998 | 218 | 17.4 | 40 | 19.9 | 85 | 26.0 | 85 | 26.7 | 3 | 1.1 | 5 | 3.9 |

| 1999–2003 | 386 | 30.8 | 74 | 36.8 | 106 | 32.4 | 56 | 17.6 | 92 | 33.3 | 58 | 44.6 |

| 2004–2008 | 378 | 30.3 | 54 | 26.9 | 88 | 26.9 | 90 | 28.3 | 110 | 39.9 | 36 | 27.7 |

| 2009–2012 | 270 | 21.6 | 33 | 16.4 | 48 | 14.7 | 87 | 27.4 | 71 | 25.7 | 31 | 23.9 |

| Mode of detection | ||||||||||||

| Screen-detected | 948 | 85.3 | 140 | 80.9 | 234 | 82.7 | 226 | 85.3 | 239 | 90.2 | 109 | 86.5 |

| Symptom-detected | 164 | 14.7 | 33 | 19.1 | 49 | 17.3 | 39 | 14.7 | 26 | 9.8 | 17 | 13.5 |

| Missing | 140 | 28 | 44 | 53 | 11 | 4 | ||||||

| Grade | ||||||||||||

| Low | 162 | 14.8 | 16 | 9.4 | 58 | 21.6 | 22 | 8.2 | 32 | 12.0 | 34 | 27.9 |

| Intermediate | 544 | 49.7 | 75 | 44.1 | 147 | 54.9 | 120 | 44.9 | 133 | 49.8 | 69 | 56.6 |

| High | 388 | 35.5 | 79 | 46.5 | 63 | 23.5 | 125 | 46.8 | 102 | 38.2 | 19 | 15.6 |

| Missing | 158 | 31 | 59 | 51 | 9 | 8 | ||||||

| Size | ||||||||||||

| <= 1 cm | 492 | 57.6 | 52 | 39.7 | 151 | 73.3 | 119 | 51.3 | 102 | 50.7 | 68 | 80.9 |

| 1.1–2 cm | 206 | 24.1 | 31 | 23.7 | 33 | 16.0 | 69 | 29.7 | 62 | 30.8. | 11 | 13.1 |

| >2 cm | 156 | 18.3 | 48 | 36.6 | 22 | 10.7 | 44 | 19.0 | 37 | 18.4 | 5 | 6.0 |

| Missing | 398 | 70 | 121 | 86 | 75 | 46 | ||||||

| ER status | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 102 | 17.7 | 29 | 34.5 | 13 | 11.5 | 53 | 34.4 | 6 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Positive | 474 | 82.3 | 55 | 65.5 | 100 | 88.5 | 101 | 65.6 | 151 | 96.2 | 67 | 98.5 |

| Missing | 676 | 117 | 214 | 164 | 119 | 62 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BCS, breast conserving surgery; ER, estrogen receptor; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

During a median 7.8 years of follow-up, 192 cases experienced a second breast cancer diagnosis for an overall rate of 1.8 per 100 person-years (Table 2). Compared to women treated with BCS alone (3.0, 95% CI: 2.3–3.7), rates of second events were lower among women who underwent mastectomy (1.4, 95% CI: 0.9 – 2.0; P=0.001), BCS plus adjuvant RT (2.0, 95% CI: 1.5 – 2.6; P=0.04), BCS plus adjuvant RT and ET (1.0, 95% CI: 0.7 – 1.5; P<0.001) and BCS plus adjuvant ET (1.2, 95% CI: 0.6 – 2.1; P=0.004).

Table 2.

Second breast cancer events according to initial treatment among 1,252 DCIS cases from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

| All (N=1,252) |

Mastectomy (N=201) |

BCS alone (N=327) |

BCS + RT (N=318) |

BCS + RT and ET (N=276) |

BCS + ET (N=130) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up (years) | 7.8 | 8.1 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 7.9 |

| Any second event, N (rate per 100 person-years) | 192 (2.0) | 24 (1.5) | 72 (3.6) | 57 (2.3) | 26 (1.1) | 13 (1.3) |

| Ipsilateral event, N | 114 | 6 | 55 | 29 | 14 | 10 |

| Contralateral event, N | 69 | 17 | 15 | 25 | 10 | 2 |

| Bilateral event, N | 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Distant events, N | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Invasive event, N | 126 | 16 | 45 | 40 | 15 | 10 |

| DCIS event, N | 66 | 8 | 27 | 17 | 11 | 3 |

| Ipsilateral invasive, N | 74 | 6 | 33 | 19 | 9 | 7 |

| Ipsilateral DCIS, N | 40 | 0 | 22 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Contralateral Invasive, N | 45 | 9 | 11 | 18 | 5 | 2 |

| Contralateral DCIS, N | 24 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 0 |

| Bilateral invasive, Na | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Bilateral DCIS, Na | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast conserving surgery. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

A bilateral diagnosis was counted as invasive if either or both breasts had an invasive second event and as DCIS if both breasts had DCIS.

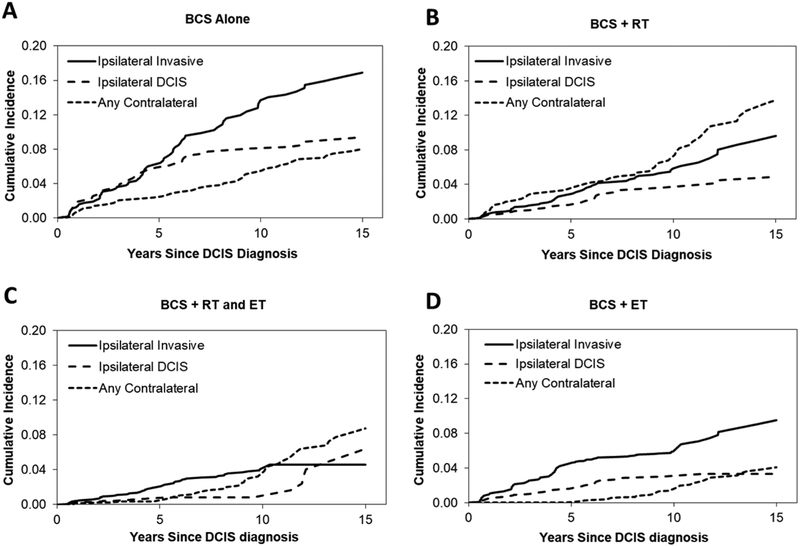

Examination of second breast cancer events during five-year intervals following the index DCIS diagnosis indicated that temporal changes in the event rates varied among treatment groups (Table 3). Women who underwent BCS with no adjuvant therapy experienced higher rates of second events during the first 10 years of follow-up, after which the annual incidence of second events decreased. In contrast, rates of second events increased slightly over time in women who underwent BCS plus adjuvant RT and increased more markedly among women who underwent BCS plus adjuvant RT and ET. The trend in each of the groups receiving radiation differed significantly from the trend observed among women who underwent BCS alone (Table 3). As a consequence, differences in the cumulative risk of second events among women who underwent BCS alone compared to those who underwent BCS with adjuvant RT diminished with increasing duration of follow-up, as illustrated by the cumulative incidence estimates (Figure 1). Women who underwent mastectomy or BCS with adjuvant ET but no RT experienced relatively constant and low rates of second events throughout the duration of follow-up (Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 3.

Incidence of a second event by treatment group and time since diagnosis among 1,252 DCIS cases from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

| Time Since Diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 years | 5–10 years | >10 years | ||||||

| Annual Incidence (%) | 95% Cl | Annual Incidence (%) | 95% Cl | Annual Incidence (%) | 95% Cl | Ptrenda | Pinteractionb | |

| BCS alone | 3.1 | 2.2 – 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.1 – 4.9 | 1.7 | 0.7 – 3.5 | 0.11 | Ref |

| BCS + RT | 1.8 | 1.1 – 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.2 – 3.2 | 2.8 | 1.6 – 4.7 | 0.20 | 0.04 |

| BCS + RT and ET | 0.7 | 0.3 – 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 – 4.4 | 2.1 | 0.8 – 4.4 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| BCS + ET | 1.4 | 0.6 – 2.8 | 0.9 | 0.2 – 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 – 4.4 | 0.97 | 0.57 |

| Ipsilateral mastectomy | 1.4 | 0.7 – 2.4 | 1.9 | 0.8 – 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 – 2.2 | 0.41 | 0.93 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast conserving surgery; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

Test for trend in annual incidence across three categories of follow-up time intervals.

Test for treatment by time since DCIS diagnosis interaction to assess differences in trend compared to BCS alone as reference group.

Fig 1.

Cumulative incidence of second events according to self-selected treatment group among 1,252 DCIS cases treated with breast conserving surgery, from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System. BCS, breast conserving surgery; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

In a competing risks analysis of ipsilateral invasive, ipsilateral DCIS, and contralateral second events in the BCS treatment groups, the hazard ratios varied significantly over time (P<0.001) for each type of event, indicating that temporal changes in the risk of that event differed among women undergoing differing treatments. These temporal effects were not the same for all three types of event and five-year interval risk estimates derived from this analysis indicate that the differences in temporal trends observed in the rates of any second breast cancer event were largely due to contralateral events (Table 4). Among women who underwent BCS without any adjuvant therapy, the probability of a contralateral second event was similar during the three time periods. In contrast, the risk of contralateral events increased over time among women receiving BCS plus adjuvant RT and/or ET.

Table 4.

Probability of first recurrence during 5-year intervals after diagnosis, conditional on no recurrence of any type in previous intervals, among 1,051 DCIS cases treated with breast conserving surgery from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

| BCS alone (N=327) |

BCS + RT (N=318) |

BCS + RT and ET (N=276) |

BCS + ET (N=130) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any event | ||||

| 0–5 years | 0.143 | 0.076 | 0.029 | 0.058 |

| 6–10 years | 0.129 | 0.086 | 0.052 | 0.045 |

| 11–15 years | 0.071 | 0.121 | 0.116 | 0.066 |

| Ipsilateral Invasive | ||||

| 0–5 years | 0.060 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.042 |

| 6–10 years | 0.077 | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.017 |

| 11–15 years | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.036 |

| Ipsilateral DCIS | ||||

| 0–5 years | 0.059 | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.016 |

| 6–10 years | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| 11–15 years | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.056 | 0.003 |

| Any contralateral | ||||

| 0–5 years | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| 6–10 years | 0.030 | 0.034 | 0.028 | 0.014 |

| 11–15 years | 0.026 | 0.070 | 0.055 | 0.027 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast conserving surgery; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in sit; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

Corresponding estimates of cumulative incidence illustrate the differing patterns in types of recurrence among the treatment groups. Similar patterns were observed for women undergoing BCS alone (Figure 2A) and BCS plus ET (Figure 2D), with ipsilateral invasive second events being the most likely. In both of these treatment groups the cumulative incidence of ipsilateral DCIS leveled off with increasing time since DCIS diagnosis, as the risk of this type of second event decreased. Among women undergoing BCS with adjuvant radiation, the cumulative incidence throughout follow-up was higher for contralateral events than either an ipsilateral DCIS or ipsilateral invasive event (Figure 2B). For women undergoing BCS plus adjuvant RT and ET, cumulative incidence was very low for both contralateral and ipsilateral DCIS second events during the first five years of follow-up but then increased for contralateral events (Figure 2C).

Fig 2.

Cumulative incidence of specific types of second events by treatment group among 1,051 DCIS cases treated with breast conserving surgery, from the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System. BCS, breast conserving surgery; ET, endocrine therapy; RT, radiation therapy.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the risk of a second event after DCIS varies during follow-up time in a treatment-dependent manner. Women treated with BCS alone experienced a declining rate of second events over time following their diagnosis. In contrast, women treated with BCS and adjuvant RT (with or without ET) experienced increasing rates of second events during the course of follow-up.

The observed differences in disease-free survival likely reflect differences in the biological types of DCIS represented in each self-selected treatment group and differences in patients’ intrinsic breast cancer risk (e.g., for new primary breast cancers), in addition to the effects of the received treatments. For example, women undergoing BCS with adjuvant RT were more likely to be younger and to have high grade, large, ER negative DCIS lesions than women undergoing BCS alone. Consequently, these DCIS lesions may be expected to have a higher risk of disease progression. In our data it appeared that RT was effective in suppressing risk of ipsilateral second events for up to 10 years, after which the incidence of second events (conditional on no previous event) exceeds that of women who underwent BCS alone.

Women treated with BCS and adjuvant ET (no radiation) were more likely to have low grade, small, ER positive DCIS lesions than women who received adjuvant RT. They may therefore be expected to have lower risk, and indeed the overall rate of second events remained low throughout the duration of the follow-up period. However, there was some suggestion that the rate of contralateral second events increased over time. The standard recommendation for the duration of adjuvant ET for DCIS during our study period was five years of treatment [2] and thus our results likely reflect the temporary suppression of contralateral events during the active treatment period, followed by gradually increasing rates after cessation of ET.

Our findings are consistent with some but not all findings from randomized trials and prior observational studies. The NASBP-B17 [7], EORTC 10853 [12], and SweDCIS [18] trials of breast conserving surgery with vs. without radiation observed that the risk of local recurrence for women treated with BCS alone is highest during the first five years and declines thereafter, as observed in our study. This pattern was also observed in a large observational study of women diagnosed with DCIS in the Netherlands [13]. The NSABP-B17, SweDCIS, and Netherlands studies also reported constant rates of contralateral events over the duration of follow-up for women with BCS alone [7,18,13], consistent with the pattern observed in our study.

For women treated with BCS plus radiation, the NASBP-B17, EORTC 10853, and SweDCIS trials observed that the rate of ipsilateral DCIS recurrence declined after 5 years but the rate of local invasive recurrence was constant over time [7,12,18]. The EORTC and SweDCIS trials reported that the protective effect of radiation against invasive ipsilateral recurrence was restricted to the first five and ten years after treatment, respectively [12]. The Netherlands observational study observed an increasing rate of ipsilateral invasive recurrences over time among women treated with BCS plus radiation and reported that the reduction in ipsilateral invasive recurrence associated with RT declines over time since diagnosis [13]. Our results are also consistent with these prior findings, with a stable or increasing rate of ipsilateral invasive events among women treated with BCS plus radiation, though we observed a relatively constant rate of ipsilateral DCIS events. Interestingly, the SweDCIS trial observed an increasing rate of contralateral events over the course of follow-up [18], similar to that observed in our study, though this was not observed in the NSABP-B17 trial [7].

In our study, women who underwent BCS with adjuvant RT and ET experienced an increasing rate of second events over time, with specific increases in ipsilateral DCIS events and contralateral events after 10 years of follow-up. These results contrast with the NASBP-B24 trial, which observed a constant rate of ipsilateral invasive and contralateral events over time among women randomized to five years of tamoxifen [7]. The UK/ANZ randomized trial observed a declining rate of second events over time among women who were randomized to five years of tamoxifen [8], though this included a mix of women who did or did not receive adjuvant RT. The reasons for these differences are not entirely clear, but likely stem from the critical difference that in our observational study patients self-selected into treatment groups based on clinical factors and personal preferences. Additionally, the randomized trials included women diagnosed in the 1980s and 1990s prior to the recognition that ET is effective only in women with hormone receptor positive disease [19]. The vast majority of women in our study who received ET were diagnosed after 1999 and had ER positive DCIS.

Our population-based cohort of women with DCIS included women treated in diverse clinical settings across Vermont. Other strengths include the long duration of follow-up and the identification of second events from pathology reports and the statewide cancer registry, rather than reliance on self-report. Although Vermont is socio-economically diverse, limitations include the lack of racial and ethnic diversity (more than 90% of women were non-Hispanic whites) and the relatively small sample size for investigating specific types of second events within treatment groups, particularly among women treated with ipsilateral mastectomy and BCS plus adjuvant ET without radiation, or among patient subgroups defined by age or other characteristics.

Our results have a number of important implications. The observed time-dependent variation in incidence of second events during the course of follow-up indicates that recurrence rates based on short-term data should not be used to predict recurrence risk in women who are disease-free at 5 or 10 years following their initial DCIS diagnosis. Doing so would overestimate the cumulative risk over extended periods of follow-up for women treated with BCS alone, while underestimating risk for women treated with adjuvant therapies. Our results also demonstrate that women receiving adjuvant ET have very low rates of second events for up to ten years following diagnosis, with apparent protection against both ipsilateral and contralateral events. However, the increasing risk of contralateral events over time among women undergoing adjuvant ET supports current guideline recommendations and suggests that women may wish to consider continued ET beyond five years to lengthen protection against second events [20].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA196383, U54 CA163303, P01 CA154292), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCS-1504–30370), and the University of Vermont Cancer Center with funds generously awarded by the Lake Champlain Cancer Research Organization (pilot grant #032800). The collection of Vermont Cancer Registry data used in this study was supported by Cooperative Agreement No. NU58DP006322 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The statements presented in this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. The authors wish to thank Drs. Andrew Goodwin, Brenda Waters, and Jill Warrington who participated in the centralized review of DCIS specimens; Alison Johnson and Jennifer Kachajian at the Vermont Cancer Registry; and Mark Bowman, Mike Butler, Rachael Chicoine, Meghan Farrington, Cindy Groseclose, Kathleen Howe, Dr. John Mace, Denis Nunez, Dawn Pelkey, Dusty Quick, and Tiffany Sharp of the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- BCS

breast conserving surgery

- CI

confidence interval

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ET

endocrine therapy

- RT

radiation therapy

- VBCSS

Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System

- VCR

Vermont Cancer Registry

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors have a financial relationship with any of the organizations that sponsored the research.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions in our data use agreements with the providers of medical records data used in this study, but de-identified aggregate data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

All procedures in this study comply with the current laws of the USA. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin K (2018) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015. National Cancer Institute; https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2018) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. V.1.2018. Available at www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf.

- 3.Sprague BL, McLaughlin V, Hampton JM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A (2013) Disease-free survival by treatment after a DCIS diagnosis in a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 141 (1):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dick AW, Sorbero MS, Ahrendt GM, Hayman JA, Gold HT, Schiffhauer L, Stark A, Griggs JJ (2011) Comparative effectiveness of ductal carcinoma in situ management and the roles of margins and surgeons. J Natl Cancer Inst 103 (2):92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falk RS, Hofvind S, Skaane P, Haldorsen T (2011) Second events following ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a register-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129 (3):929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C, Wang Y, Clarke M, Davies C, Peto R, Bijker N, Solin L, Darby S (2010) Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010 (41):162–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, Mamounas EP, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Land SR, Margolese RG, Swain SM, Costantino JP, Wolmark N (2011) Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst 103 (6):478–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Pinder SE, Ellis IO, Forsyth S, Bundred NJ, Forbes JF, Bishop H, Fentiman IS, George WD (2011) Effect of tamoxifen and radiotherapy in women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ: long-term results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Lancet Oncol 12 (1):21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz SJ, Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Deapen D, Salem B, Lakhani I, Morrow M (2005) Patterns and correlates of local therapy for women with ductal carcinoma-in-situ. J Clin Oncol 23 (13):3001–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercieca-Bebber R, King MT, Boxer MM, Spillane A, Winters ZE, Butow PN, McPherson J, Rutherford C (2017) What quality-of-life issues do women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) consider important when making treatment decisions? Breast Cancer 24 (5):720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TT, Hoskin TL, Day CN, Habermann EB, Goetz MP, Boughey JC (2017) Factors Influencing Use of Hormone Therapy for Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: A National Cancer Database Study. Ann Surg Oncol 24 (10):2989–2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donker M, Litiere S, Werutsky G, Julien JP, Fentiman IS, Agresti R, Rouanet P, de Lara CT, Bartelink H, Duez N, Rutgers EJ, Bijker N (2013) Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma In Situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 31 (32):4054–4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elshof LE, Schaapveld M, Schmidt MK, Rutgers EJ, van Leeuwen FE, Wesseling J (2016) Subsequent risk of ipsilateral and contralateral invasive breast cancer after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: incidence and the effect of radiotherapy in a population-based cohort of 10,090 women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159 (3):553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprague BL, Bolton KC, Mace JL, Herschorn SD, James TA, Vacek PM, Weaver DL, Geller BM (2014) Registry-based study of trends in breast cancer screening mammography before and after the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Radiology 270 (2):354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehman CD, Arao RF, Sprague BL, Lee JM, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, Henderson LM, Onega T, Tosteson AN, Rauscher GH, Miglioretti DL (2017) National Performance Benchmarks for Modern Screening Digital Mammography: Update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology 283 (1):49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Radiology (2013) ACR BI-RADS® - Mammography 5th Edition In: ACR BI-RADS Atlas: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. American College of Radiology, Reston, VA, [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleiss JL (1981) Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warnberg F, Garmo H, Emdin S, Hedberg V, Adwall L, Sandelin K, Ringberg A, Karlsson P, Arnesson LG, Anderson H, Jirstrom K, Holmberg L (2014) Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ: 20 years follow-up in the randomized SweDCIS Trial. J Clin Oncol 32 (32):3613–3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allred DC, Anderson SJ, Paik S, Wickerham DL, Nagtegaal ID, Swain SM, Mamounas EP, Julian TB, Geyer CE Jr., Costantino JP, Land SR, Wolmark N (2012) Adjuvant tamoxifen reduces subsequent breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor-positive ductal carcinoma in situ: a study based on NSABP protocol B-24. J Clin Oncol 30 (12):1268–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, Buchholz TA, Davidson NE, Gelmon KE, Giordano SH, Hudis CA, Rowden D, Solky AJ, Stearns V, Winer EP, Griggs JJ (2014) Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 32 (21):2255–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]