Abstract Abstract

Four new species in Trechisporales from East Asia, Dextrinocystiscalamicola, Subulicystidiumacerosum, S.tropicum and Tubuliciumbambusicola, are described and illustrated, based on morphological and molecular evidence. The phylogeny of Trechisporales was inferred from a combined dataset of ITS-nrLSU sequences. In the phylogenetic tree, Sistotremastrum formed a family-level clade of its own, sister to the Hydnodontaceae clade formed by all other genera. Dextrinocystis, is for the first time, confirmed as a member of Hydnodontaceae. A key to all the accepted genera in Trechisporales is given.

Keywords: Hydnodontaceae , Sistotremastrum family, phylogeny, taxonomy, wood-inhabiting fungi

Introduction

Trechisporales K.H. Larss. is a rather small but strongly supported order in Agaricomycotina (Hibbett et al. 2007; Larsson 2007). At present, eight to twelve genera, Brevicellicium K.H. Larss. & Hjortstam, Fibriciellum J. Erikss. & Ryvarden, FibrodontiaParmasto, Luellia K.H. Larss. & Hjortstam, Porpomyces Jülich, Subulicystidium Parmasto, Trechispora P. Karst. (type genus, including Cristelloporia I. Johans. & Ryvarden, Echinotrema Park-Rhodes, Hydnodon Banker and Scytinopogon Singer) and Tubulicium Oberw., are placed in the family Hydnodontaceae, while Sistotremastrum J. Erikss. should be placed in a family of its own (Larsson 2001, 2007; Larsson et al. 2004; Binder et al. 2005; Hibbett et al. 2007, 2014; Birkebak et al. 2013; Telleria et al. 2013a). In addition, four genera, Dextrinocystis Gilb. & M. Blackw., Dextrinodontia Hjortstam & Ryvarden, Brevicellopsis Hjortstam & Ryvarden and Litschauerella Oberw. were listed as possible candidates of Hydnodontaceae waiting for molecular confirmation (Larsson 2007; Hibbett et al. 2014). Except for Scytinopogon and Trechisporathelephora (Lév.) Ryvarden, all the taxa in Trechisporales have resupinate basidiomata and most of them have a non-poroid hymenophore (Fig. 1, Albee-Scott and Kropp 2011; Hibbett et al. 2014). However, the microscopic characters vary significantly amongst different genera and some of them were surprisingly placed in the order solely based on molecular phylogeny (Larsson 2007; Bernicchia and Gorjón 2010).

Figure 1.

Basidiomata of Trechisporales. aScytinopogonpallescens (Bres.) Singer (He 5192) bPorpomycessubmucidus F. Wu & C.L. Zhao (Dai 13708) cFibrodontiaalba Yurchenko & Sheng H. Wu (He 4761) dTrechispora sp. (He 5491) eSubulicystidium sp. (He 3048) fTubuliciumraphidisporum (Boidin & Gilles) Oberw., Kisim.-Hor. & L.D. Gómez (He 3191). Scale bar: 1 cm.

Except for Trechispora, the largest genus in the order, most genera in Trechisporales have mostly few species and some are still monotypic. However, in recent years, many new species have been described, based on both DNA sequence data and morphological characters. Wu et al. (2015) described a cryptic species of Porpomycesmucidus (Pers.) Jülich, based mainly on sequence data. Ordynets et al. (2018) studied the short-spored species of Subulicystidium and recognised eleven new species. Tens specimens of Trechisporales were collected from East Asia by the senior authors in the past three years. The purposes of the present paper are to study these specimens by using morphological and molecular methods and discuss the phylogeny of the Trechisporales, based on expanded sampling.

Materials and methods

Morphological studies

Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbaria of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China (BJFC) and in the Centre for Forest Mycology Research, U.S. Forest Service, Madison, USA (CFMR). Freehand sections were made from dried basidiomata and mounted in 0.2% cotton blue in lactic acid, 1% phloxine (w/v) or Melzer’s reagent. Microscopic examinations were carried out with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Corporation, Japan) at magnifications up to 1000×. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. All measurements were carried out with sections mounted in Melzer’s reagent. The following abbreviations are used: L = mean spore length, W = mean spore width, Q = L/W ratio, n (a/b) = number of spores (a) measured from given number of specimens (b). Colour names and codes follow Kornerup and Wanscher (1978).

DNA extraction and sequencing

The CTAB plant genome rapid extraction kit DN14 (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co. Ltd, Beijing) was used for DNA extraction and PCR amplification from dried specimens. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and partial nrLSU markers were amplified with the primer pairs ITS5/ITS4 (White et al. 1990) and LR0R/LR7 (Vilgalys and Hester 1990). The PCR procedures followed Liu et al. (2017). DNA sequencing was performed at Beijing Genomics Institute and the sequences were deposited in GenBank (Benson et al. 2018). The sequence quality control followed Nilsson et al. (2012). BioEdit v.7.0.5.3 (Hall 1999) and Geneious v.11.1.15 (Kearse et al. 2012) were used for chromatogram check and contig assembly.

Phylogenetic analyses

The molecular phylogeny was inferred from a combined dataset of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2-nrLSU sequences of Trechisporales sensu Larsson (2007) (Table 1). Hyphodontiafloccosa (Bourdot & Galzin) J. Erikss. and H.subalutacea (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. were selected as the outgroup (Wu et al. 2015). The sequences of ITS and nrLSU were aligned separately using MAFFT v.7 (Katoh et al. 2017, http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) with the G-INS-i iterative refinement algorithm. The separate alignments were concatenated using Mesquite v.3.5.1 (Maddison and Maddison 2018). The combined alignments were deposited in TreeBase (http://treebase.org/treebase-web/home.html, submission ID: 23620).

Table 1.

Species and sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Taxa | Voucher | Locality | ITS | nrLSU | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brevicellicium exile | MA-Fungi 26554 | Spain | HE963777 | HE963778 | Telleria et al. (2013a) |

| B. olivascens | MA-Fungi 41366 | Spain | HE963785 | HE963786 | Telleria et al. (2013a) |

| B. sp | MPM 2012 | Portugal | – | HE963774 | Telleria et al. (2013a) |

| Dextrinocystis calamicola | BJFC: He 5693 | China | MK204533 | MK204546 | This study |

| D. calamicola | BJFC: He 5700 | China | MK204534 | MK204547 | This study |

| BJFC: He 5701 | China | – | MK204548 | This study | |

| Fibrodontia alba | TNM: F25503 | Taiwan | JQ612713 | JQ612714 | Yurchenko and Wu (2014) |

| F. alba | BJFC: He 4761 | China | MK204529 | MK204541 | This study |

| F. brevidens | TNM: Wu 9807-16 | Taiwan | KC928276 | KC928277 | Yurchenko and Wu (2014) |

| BJFC: He 3559 | China | MK204528 | – | This study | |

| F. gossypina | AFTOL-ID 599 | – | DQ249274 | AY646100 | Unpublished |

| Hyphodontia floccosa | GB: Berglund 150-02 | Sweden | DQ873618 | DQ873617 | Larsson et al. (2006) |

| H. subalutacea | GEL 2196 | – | DQ340341 | DQ340362 | Unpublished |

| Litschauerella sp. | BJFC: He 3171 | China | MK204555 | MK204556 | This study |

| Porpomyces mucidus | BJFC: Dai 12692 | Czech Republic | KT157833 | KT157838 | Wu et al. (2015) |

| P. submucidus | BJFC: Cui 5183 | China | KT152143 | KT152145 | Wu et al. (2015) |

| Subulicystidium boidinii | KAS: L 1584a | Reunion | MH041527 | – | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. acerosum | BJFC: He 3804 | China | MK204539 | MK204543 | This study |

| S. brachysporum | O: F: KHL 16100 | Brazil | MH000599 | MH000599 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| BJFC: He 2207 | USA | MK204532 | MK204549 | This study | |

| S. fusisporum | GB: KHL 10360 | Puerto Rico | MH041535 | MH041567 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. grandisporum | O: F: 506781 | Costa Rica | MH041547 | MH041592 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. harpagum | KAS: L 1726a | Reunion | MH041532 | MH041588 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. inornatum | GB: KHL 10444 | Puerto Rico | MH041558 | MH041569 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. longisporum | GB: KHL 14229 | Sweden | MH000601 | MH000601 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| BJFC: He 2981 | China | – | MK204550 | This study | |

| S. meridense | GB: Hjm 16400 | Brazil | MH041538 | MH041604 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. nikau | KAS: L 1296 | Reunion | MH041513 | MH041565 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. obtusisporum | FR: Piepenbrink & Lotz-Winter W213-3-I | Germany | MH041521 | MH041566 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. parvisporum | KAS: L 0140 | Reunion | MH041529 | MH041590 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. perlongisporum | TU 124388 | Italy | UDB028355 | UDB028355 | Kõljalg et al. (2013) |

| GB: KHL 16062 | Brazil | MH000600 | MH000600 | Ordynets et al. (2018) | |

| S. rarocrystallinum | O: F: 918488 | Colombia | MH041512 | MH041564 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. robustius | GB: KHL 10813 | Jamaica | MH041514 | MH041608 | Ordynets et al. (2018) |

| S. tedersooi | TU 110894 | Vietnam | UDB014161 | – | Kõljalg et al. (2013) |

| S. tropicum | BJFC: He 3968 | China | MK204531 | MK204544 | This study |

| BJFC: He 3583 | China | MK204530 | MK204542 | This study | |

| Scytinopogon angulisporus | TFB 13611 | USA | – | JQ684661 | Unpublished |

| S. havencampii | SFSU: DED 8300 | Príncipe island | KT253946 | KT253947 | Desjardin and Perry (2015) |

| S. pallescens | BJFC: He 5192 | Vietnam | – | MK204553 | This study |

| Sistotremastrum guttuliferum | MA-Fungi 82105 | Portugal | JX310445 | – | Telleria et al. (2013b) |

| S. guttuliferum | BJFC: He 3338 | China | MK204540 | MK204552 | This study |

| S. niveocremeum | CBS 427.54 | France | MH857380 | MH868920 | Vu et al. (2019) |

| S. suecicum | GB: KHL11849 | Sweden | EU118666 | EU118667 | Larsson (2007) |

| Trechispora alnicola | AFTOL-ID 665 | – | – | AY635768 | Unpublished |

| T. araneosa | GB: KHL 8570 | Sweden | AF347084 | AF347084 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

| T. bispora | CBS 142.63 | Australia | MH858241 | MH869842 | Vu et al. (2019) |

| T. confinis | GB: KHL 11064 | Sweden | AF347081 | AF347081 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

| T. farinacea | TUB 011825 | Germany | EU909231 | EU909231 | Krause et al. (2011) |

| T. hymenocystis | GB: KHL 8795 | Sweden | AF347090 | AF347090 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

| T. kavinioides | GB: KGN 981002 | Norway | AF347086 | AF347086 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

| T. mollusca | CBS 439.48 | Canada | MH856428 | – | Vu et al. (2019) |

| T. nivea | GB: G. Kristiansen | Norway | – | AY586720 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

| Tubulicium bambusicola | BJFC: He 4776 | China | MK204536 | MK204551 | This study |

| T. bambusicola | BJFC: He 4058 | Thailand | MK204535 | – | This study |

| T. raphidisporum | BJFC: He 2851 | China | MK204538 | MK204554 | This study |

| BJFC: He 3191 | China | MK204537 | MK204545 | This study | |

| T. vermiculare | GEL 5015 | – | AJ406424 | – | Langer (2002) |

| T. vermiferum | GB: KHL 8714 | Norway | – | AY463477 | Larsson et al. (2004) |

For both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI), a partitioned analysis was performed with the following four partitions: ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2 and nrLSU. The ML analysis was performed using RAxML v.8.2.10 (Stamatakis 2014) with the bootstrap values (ML-BS) obtained from 1,000 replicates and the GTRGAMMA model of nucleotide evolution. The BI was performed using MrBayes 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. 2012). The best-fit substitution model for each partitioned locus was estimated separately with jModeltest v.2.17 (Darriba et al. 2012) by restricting the search to models that can be implemented in MrBayes. Two runs of four Markov chains were run for 4,000,000 generations until the split deviation frequency value was lower than 0.01. The convergence of the runs was checked using Tracer v.1.7 (Rambaut et al. 2018). Trees and model parameters were sampled every 100th generation. The first quarter of the trees, which represented the burn-in phase of the analyses, was discarded and the remaining trees were used to build a majority rule consensus tree and to calculate Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP). All trees were visualised in FigTree 1.4.2 (Rambaut 2014).

Results

Phylogenetic inference

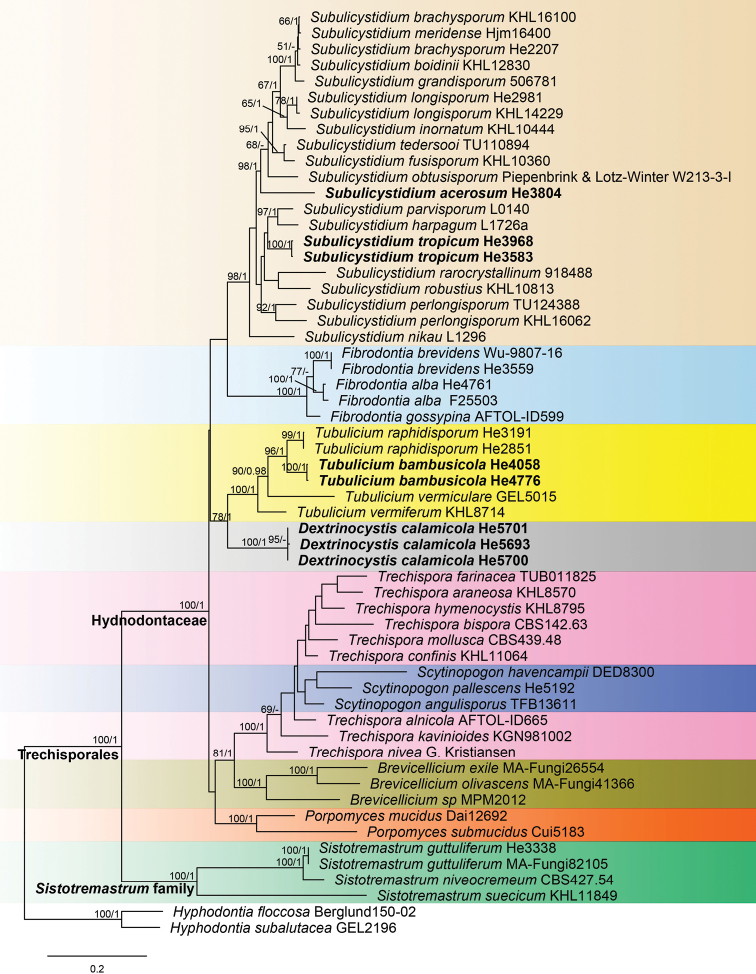

The ITS-nrLSU sequence dataset contained 50 ITS and 51 nrLSU sequences from 58 samples representing 45 ingroup taxa and the outgroup (Table 1). Fourteen ITS and 15 nrLSU sequences were generated for this study. jModelTest suggested GTR+G, SYM+I+G, GTR+I+G and GTR+I+G to be the best-fit models of nucleotide evolution for ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2 and nrLSU markers, respectively, for the Bayesian analysis. BI analysis resulted in an almost identical tree topology compared to the ML analysis and no significant conflicts were found between the two analyses. Only the ML tree is shown in Fig. 2 with ML bootstrap values ≥ 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95 labelled along the branches.

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of Trechisporales inferred from ITS-nrLSU sequences. Topology is from ML analysis with maximum likelihood bootstrap support values (≥ 50, former) and Bayesian posterior probability values (≥ 0.95, latter) shown along the branches. Different genera are indicated as coloured blocks. The new species are set in bold. Scale bar: 0.2 nucleotide substitutions per site.

In the tree (Fig. 2), two large clades, corresponding to Hydnodontaceae and Sistotremastrum family, were strongly supported. Except for Sistotremastrum, the other eight genera sampled were nested within the Hydnodontaceae clade. The genera Brevicellicium, Fibrodontia, Porpomyces and Subulicystidium were strongly supported as monophyletic lineages. Dextrinocystiscalamicola, the first species sequenced in the genus, formed a sister lineage to Tubulicium with relatively strong support (ML-BS = 78%, BPP = 1). The three species of Scytinopogon were nested within the Trechispora lineage. Subulicystidiumacerosum and S.tropicum formed distinct lineages in the genus, while Tubuliciumbambusicola is closely related to T.raphidisporum.

Taxonomy

Dextrinocystis calamicola

S.H. He & S.L. Liu sp. nov.

828718

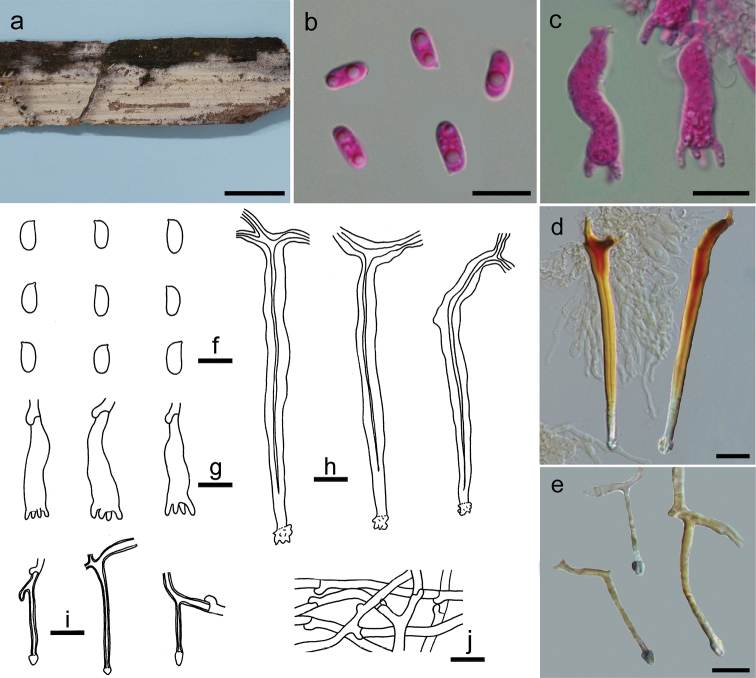

Figure 3.

Dextrinocystiscalamicola (holotype, He 5701). a basidiomata b, f basidiospores c, g basidia d, h cystidia e, i cystidia-like branches in subiculum j subicular hyphae. Scale bars: 1 cm (a), 10 µm (b–j). b, c Taken in phloxine d, e taken in Melzer’s reagent.

Typification.

CHINA. Fujian Province, Wuyishan County, Wuyishan Nature Reserve, on dead culms of Calamus, 3 Oct 2018, He 5701 (holotype, BJFC 026763).

Etymology.

“calamicola” refers to growing on Calamus.

Basidiomata.

Annual, resupinate, effused, thin, soft, easily separated from the substrate, at first as irregular small patches, later confluent up to 15 cm long, 2 cm wide. Hymenophore surface smooth, orange white (5A2) to greyish-orange [5B(3–5)], finely cracked with age; margin thinning out, fimbriate, slightly paler than hymenophore surface, becoming indistinct with age.

Microscopic structures.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, hyaline, thin-walled, frequently branched and septate, loosely interwoven, 2–3 µm in diam. Cystidia-like branches present, branched from subicular hyphae, embedded, hyaline, thick-walled, encrusted at apex, 20–30 × 1.5–2 µm. Hymenial cystidia abundant, subulate, projecting beyond hymenium, bi- or multi-rooted, hyaline, distinctly thick-walled with a narrow lumen, slightly encrusted at apex, distinctly dextrinoid, 50–110 × 5–6 µm. Basidia suburniform to subclavate, hyaline, thin-walled, with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 20–30 × 5–8 µm; sterigmata mostly cylindrical with a blunt tip; basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller. Basidiospores abundant, oblong ellipsoid to short cylindrical, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, negative in Melzer’s reagent, acyanophilous, (7–)7.5–8.8(–9) × (3.2–)3.3–4 µm, L = 8.1 µm, W = 3.7 µm, Q = 2.1–2.2 (n = 60/2).

Additional specimens examined.

CHINA. Fujian Province, Wuyishan County, Wuyishan Nature Reserve, on dead culms of Calamus, 3 Oct 2018, He 5693 (BJFC 026755) & He 5700 (BJFC 026762).

Remarks.

The thin whitish basidiomata on a palm tree, distinctly thick-walled cystidia with a dextrinoid reaction in Melzer’s reagent, presence of small cystidia-like branches and short cylindrical basidiospores indicate that the new species is a member of Dextrinocystis. Two species, D.capitata (D.P. Rogers & Boquiren) Gilb. & M. Blackw. and D.macrospora (Liberta) Nakasone have been reported in the genus, both of which differ from D.calamicola by having much larger basidiospores (11–14 × 3–4 µm for D.capitata in Gilbertson and Blackwell 1988; 12–19 × 4.5–7 µm for D.macrospora in Liberta 1960) and a distribution in America. In the phylogenetic tree, D.calamicola formed a sister lineage to Tubulicium with relatively strong support (Fig. 2).

Subulicystidium acerosum

S.H. He & S.L. Liu sp. nov.

828719

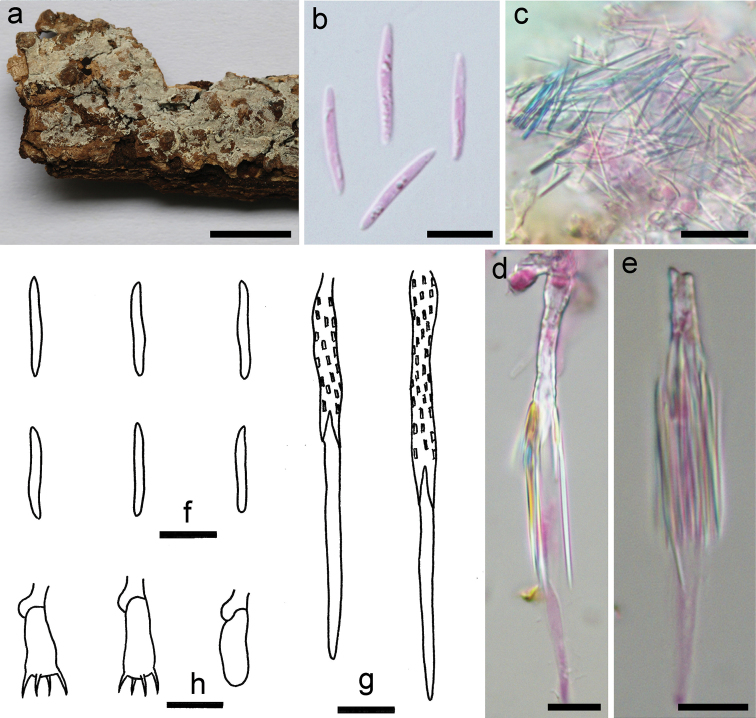

Figure 4.

Subulicystidiumacerosum (holotype, He 3804). a basidiomata b, f basidiospores c acerose crystals d, e, g cystidia h basidia and a basidiole. Scale bars: 1 cm (a), 10 µm (b–h). b–e Taken in phloxine.

Typification.

CHINA. Guizhou Province, Libo County, Maolan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 16 Jun 2016, He 3804 (holotype, BJFC 022303).

Etymology.

“acerosum” refers to the presence of numerous needle-like crystals.

Basidiomata.

Annual, resupinate, effused, very thin, easily separated from the substrate, up to 6 cm long, 2 cm wide. Hymenophore surface smooth, more or less arachnoid, white (5A1) to orange grey (5B2); margin undifferentiated.

Microscopic structures.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, hyaline, thin-walled, frequently branched and septate, loosely interwoven, 2–3.5 µm in diam. Cystidia abundant, subulate, projecting beyond hymenium, hyaline, thick-walled and regularly covered with rectangular crystals at basal part, thin-walled and smooth at apex part, 50–100 × 3–5 µm. Crystals numerous, distributed in whole section or more commonly attached on cystidia, acerose, hyaline. Basidia short clavate, hyaline, thin-walled, with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 15–20 × 4–5.5 µm; basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller. Basidiospores narrowly fusiform to slightly vermicular, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, negative in Melzer’s reagent, acyanophilous, (14.5–)15.5–18(–20) × 1.8–2.2 µm, L = 16.6 µm, W = 2 µm, Q = 8.3 (n = 30/1).

Remarks.

Subulicystidiumacerosum is characterised by the long and narrow basidiospores and presence of numerous acerose crystals. The species is similar to S.longisporum (Pat.) Parmasto, which differs in having slightly shorter and wider basidiospores (12–16 × 2–3 µm, Q < 7, Ordynets et al. 2018). Subulicystidiumcochleum Punugu is similar to S.acerosum by sharing needle-like crystals but differs in having larger basidiospores (20–27 × 2–3 µm, Punugu et al. 1980; Ordynets et al. 2018). Phylogenetically, S.acerosum is distinct from all the other sampled species of Subulicystidium (Fig. 2).

Subulicystidium tropicum

S.H. He & S.L. Liu sp. nov.

828720

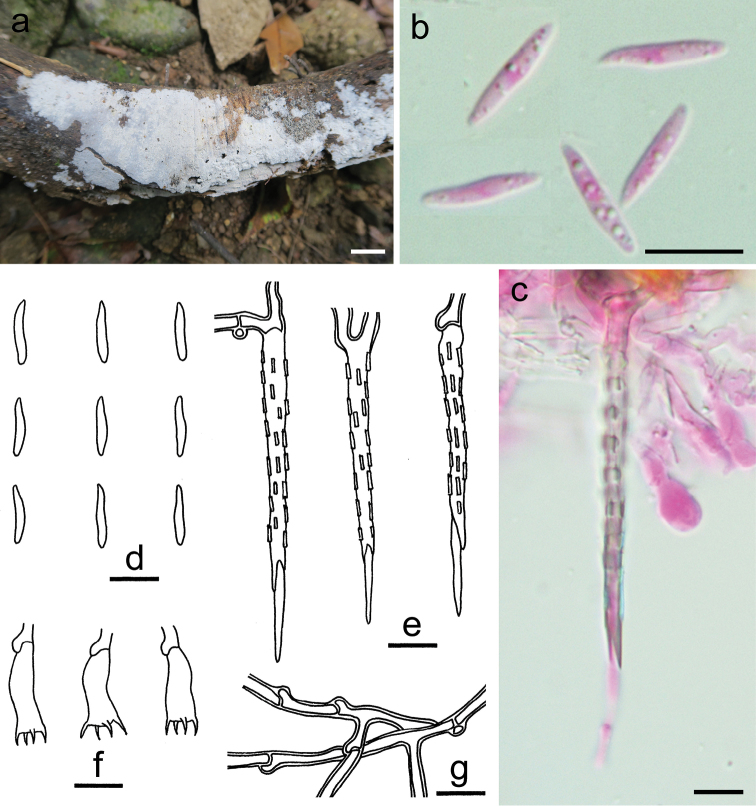

Figure 5.

Subulicystidiumtropicum (holotype, He 3968). a basidiomata b, d basidiospores c, e cystidia f basidia g subicular hyphae. Scale bars: 1 cm (a), 10 µm (b–g). b, c Taken in phloxine.

Typification.

CHINA. Hainan Province, Wuzhishan County, Wuzhishan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 10 Jun 2016, He 3968 (holotype, BJFC 022470).

Etymology.

“tropicum” refers to the distribution in tropical areas.

Basidiomata.

Annual, resupinate, effused, very thin, separable from the substrate, up to 10 cm long, 3 cm wide. Hymenophore surface smooth, white (5A1), orange grey (5B2) to greyish-orange [5B(3–4)], not cracked; margin undifferentiated.

Microscopic structures.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, hyaline, slightly thick-walled, frequently branched and septate, loosely interwoven, 2–3.5 µm in diam. Cystidia abundant, subulate, projecting beyond hymenium, hyaline, thick-walled and regularly covered with rectangular crystals except at the apex, 40–70 × 3–5 µm. Basidia subclavate to suburniform, hyaline, thin-walled, with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 12–17 × 4–5 µm; basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller. Basidiospores fusiform to slightly vermicular, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, negative in Melzer’s reagent, acyanophilous, 11–12.5(–13) × 1.8–2.2 µm, L = 11.9 µm, W = 2 µm, Q = 5.95 (n = 30/1).

Additional specimens examined.

CHINA. Hainan Province, Baoting County, Qixianling Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 18 Mar 2016, He 3583 (BJFC 022083).

Remarks.

Subulicystidiumtropicum resembles S.acerosum and S.perlongisporum Boidin & Gilles by sharing narrow basidiospores in the genus, but differs from S.acerosum in having shorter basidiospores and lacking the needle-like crystals and from S.perlongisporum in having much shorter basidiospores and a tropical distribution (16–25 × 1.5–2.5 µm for S.perlongisporum in Ordynets et al. 2018). The new species is also similar to S.longisporum, but differs in having slender basidiospores and a tropical distribution. In the phylogenetic tree, S.tropicum formed a distinct lineage in Subulicystidium (Fig. 2).

Tubulicium bambusicola

S.H. He & S.L. Liu sp. nov.

828721

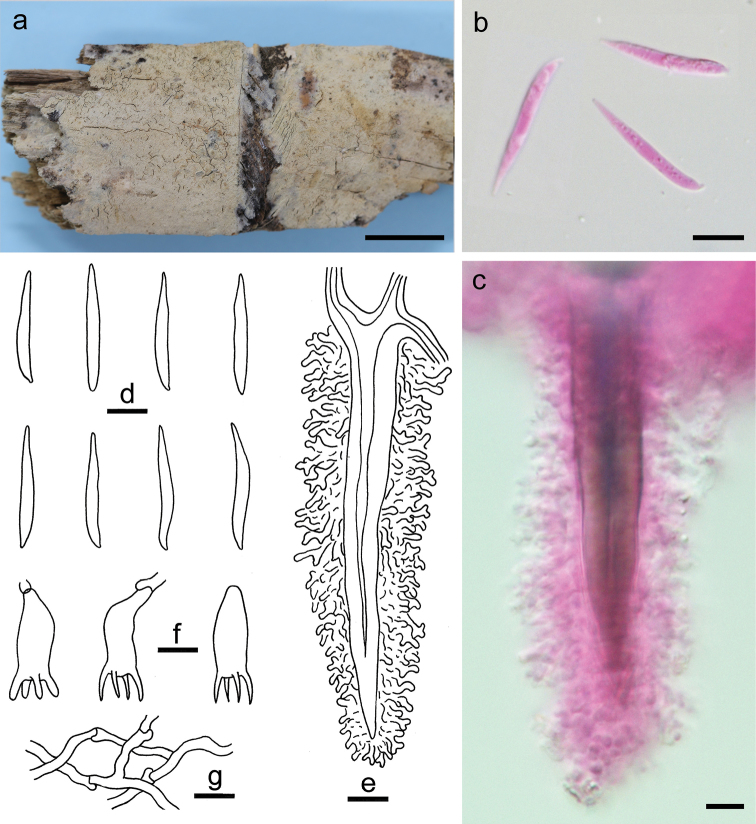

Figure 6.

Tubuliciumbambusicola (holotype, He 4058). a basidiomata b, d basidiospores c, e cystidia f basidia and a basidiole g subicular hyphae. Scale bars: 1 cm (a), 10 µm (b–g). b, c Taken in phloxine.

Typification.

THAILAND. Chiang Rai Province, Doi Mae Salong, on dead culms of bamboo, 22 Jul 2016, He 4058 (holotype, BJFC 023499).

Etymology.

“bambusicola” refers to growing on bamboo.

Basidiomata.

Annual, resupinate, effused, closely adnate, thin, at first as irregular small patches, later confluent up to 15 cm long, 5 cm wide. Hymenophore surface smooth, pilose under lens due to the projecting cystidia, pale orange (5A3) to greyish-orange [5B(3–6)], finely cracked with age; margin undifferentiated.

Microscopic structures.

Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae with clamp connections, hyaline, thin-walled, moderately branched, frequently septate, loosely interwoven, 2–3 µm in diam. Cystidia abundant, subulate, projecting beyond hymenium, multi-rooted, hyaline, distinctly thick-walled, slightly amyloid, covered with dendroid branching hyphae, 70–100 × 10–16 µm. Basidia subclavate, hyaline, thin-walled, with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 18–25 × 8–10 µm; basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller. Basidiospores narrowly fusiform to vermicular, bi-apiculate, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, negative in Melzer’s reagent, acyanophilous, (17–)20–29(–30) × (2–)2.2–3(–3.2) µm, L = 23.9 µm, W = 2.6 µm, Q = 9–9.5 (n = 60/2).

Additional specimens examined.

CHINA. Guizhou Province, Libo County, Maolan Nature Reserve, on rotten culms of bamboo, 11 Jul 2017, He 4776 (BJFC 024293).

Remarks.

Tubuliciumbambusicola is distinguished by its large vermicular basidiospores and growing on bamboo. Three taxa, T.raphidisporum (Boidin & Gilles) Oberw., Kisim.-Hor. & L.D. Gómez, T.vermiferum (Bourdot) Oberw. and T.vermiferumvar.hexasterigmatum J. Kaur & Dhingra are similar to T.bambusicola by sharing long vermicular basidiospores but differ in the width of basidiospores (≥ 3.5 µm) and growing on woody plant. Tubuliciumjunci-acuti Boidin & Gaignon on Juncusacutus differs from T.bambusicola by having shorter and wider basidiospores (15–20 × 3–4.25 µm, Boidin and Gaignon 1992).

Discussion

Nine genera in the Trechisporales were included in the present analyses and the results mostly agree with previous studies (Larsson 2007; Birkebak et al. 2013; Telleria et al. 2013a). Most of the sampled genera were retrieved as monophyletic except Scytinopogon, which was nested within the Trechispora lineage (Fig. 2). A Dextrinocystis species was sequenced for the first time and its position in Hydnodontaceae was confirmed. As indicated by the morphology (Burdsall and Nakasone 1983; Gilbertson and Blackwell 1988; Moreno and Esteve-Raventós 2007; Nakasone 2013), the genus is closely related to Tubulicium. However, Tubulicium is morphologically heterogenous, with different basidiospores (Moreno and Esteve-Raventós 2007; Hjortstam and Ryvarden 2008) and only species with fusiform to vermicular basidiospores were sequenced. Moreover, Dextrinocystis is well distinguished from Tubulicium by its distinctly dextrinoid cystida and cylindrical basidiospores (Gilbertson and Blackwell 1988; Nakasone 2013). Thus, at present, the authors prefer to retain them as separate genera until more species are sequenced.

Subulicystidium is a well-circumscribed genus characterised by the unique cystidia encrusted with rectangular crystals and fusiform to vermicular basidiospores (Bernicchia and Gorjón 2010; Ordynets et al. 2018). Although all the sampled species formed a strongly supported lineage in the tree (Fig. 2), the species S.oberwinkleri Ordynets, Riebesehl & K.H.Larss. was not congeneric with other species and excluded from our analyses. Ordynets et al. (2018) showed that S.oberwinkleri formed a distinct basal lineage in the ITS-nrLSU tree. The phylogenetic position of the species in Trechisporales needs to be further studied.

Key to accepted genera in Trechisporales

| 1 | Basidiomata clavarioid | Scytinopogon |

| – | Basidiomata resupinate or stipitate hydnoid | 2 |

| 2 | Hymenophore poroid | 3 |

| – | Hymenophore non-poroid | 4 |

| 3 | Basidiospores smooth | Porpomyces |

| – | Basidiospores ornamented | Trechispora p.p. |

| 4 | Basidiomata brown | Luellia |

| – | Basidiomata light coloured | 5 |

| 5 | Cystidia present, large and distinct | 6 |

| – | Cystidia absent or indistinct | 8 |

| 6 | Cystidia distinctly dextrinoid in Melzer’s reagent | Dextrinocystis |

| – | Cystidia negative or amyloid in Melzer’s reagent | 7 |

| 7 | Cystidia regularly encrusted with rectangular crystals | Subulicystidium |

| – | Cystidia usually covered with dendroid hyphae | Tubulicium |

| 8 | Generative hyphae with ampullate septa | Trechispora p.p. |

| – | Generative hyphae without ampullate septa | 9 |

| 9 | Subhymenial hyphae isodiametric | Brevicellicium |

| – | Subhymenial hyphae not isodiametric | 10 |

| 10 | Hyphal system dimitic; basidia with 4 sterigmata | Fibrodontia |

| – | Hyphal system monomitic; basidia with 4–8 sterigmata | Sistotremastrum |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Karen Nakasone (Center for Forest Mycology Research, Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Madison, USA) for literature loan and critical suggestions on the manuscript. This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2016ZCQ04) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31750001 & 31670013).

Citation

Liu SL, Ma HX, He SH, Dai YC (2019) Four new corticioid species in Trechisporales (Basidiomycota) from East Asia and notes on phylogeny of the order. MycoKeys 48: 97–113. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.48.31956

Contributor Information

Shuang-Hui He, Email: shuanghuihe@yahoo.com.

Yu-Cheng Dai, Email: yuchengd@yahoo.com.

References

- Albee-Scott S, Kropp BR. (2011) A phylogenetic study of Trechisporathelephora. Mycotaxon 114: 395–399. 10.5248/114.395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Sayers EW. (2018) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Research 46: D41–D47. 10.1093/nar/gkx1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bernicchia A, Gorjón SP. (2010) Fungi Europaei 12. Corticiaceae s.l. Edizioni Candusso, Italia, 1008 p.

- Binder M, Hibbett DS, Larsson KH, Larsson E, Langer E, Langer G. (2005) The phylogenetic distribution of resupinate forms across the major clades of mushroom-forming fungi (Homobasidiomycetes). Systematics and Biodiversity 3: 113–157. 10.1017/S1477200005001623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birkebak JM, Mayor JR, Ryberg KM, Matheny PB. (2013) A systematic, morphological and ecological overview of the Clavariaceae (Agaricales). Mycologia. 105: 896–911. 10.3852/12-070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boidin J, Gaignon M. (1992) Tubuliciumjunci-acuti nov. sp. (Basidiomycotina) en provenance de la Corse. Bulletin Mensuel de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon 61: 260–264. 10.3406/linly.1992.11001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burdsall Jr HH, Nakasone KK. (1983) Species of effused Aphyllophorales (Basidiomycotina) from the southeastern United States. Mycotaxon 17: 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. (2012) jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods 9: 772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Desjardin DE, Perry BA. (2015) A new species of Scytinopogon from the island of Príncipe, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. Mycosphere 6: 434–441. 10.5943/mycosphere/6/4/5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson RL, Blackwell M. (1988) Some new or unusual corticioid fungi from the Gulf Coast region. Mycotaxon 33: 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. (1999) Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, et al. (2007) A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycological Research 111: 509–547. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Bauer R, Binder M, Giachini AJ, Hosaka K et al. (2014) 14 Agaricomycetes. In: McLaughlin DJ, Spatafora JW. (Eds) Systematics and Evolution.The Mycota VII Part A. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 373–429. 10.1007/978-3-642-55318-9_14 [DOI]

- Hjortstam K, Ryvarden L. (2008) Corticioid species (Basidiomycotina, Aphyllophorales) from Colombia IV. Synopsis Fungorum 25: 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. (2017) MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kõljalg U, Nilsson RH, Abarenkov K, Tedersoo L, Taylor AFS, et al. (2013) Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Molecular Ecology 22: 5271–5277. 10.1111/mec.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup A, Wanscher JH. (1978) Methuen handbook of colour. 3rd Ed. Eyre Methuen, London, 252 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Krause C, Garnica S, Bauer R, Nebel M. (2011) Aneuraceae (Metzgeriales) and tulasnelloid fungi (Basidiomycota) – a model for early steps in fungal symbiosis. Fungal Biology 115: 839–851. 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer E. (2002) Phylogeny of non-gilled and gilled Basidiomycetes: DNA sequence inference, ultrastructure and comparative morphology. Habilitationsschrift, Tübingen University, Tübingen.

- Larsson KH. (2001) The position of Poriamucida inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Harvard Papers in Botany 6: 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KH. (2007) Re-thinking the classification of corticioid fungi. Mycological Research 111: 1040–1063. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KH, Larsson E, Kõljalg U. (2004) High phylogenetic diversity among corticioid Homobasidiomycetes. Mycological Research 108: 983–1002. 10.1017/S0953756204000851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KH, Parmasto E, Fischer M, Langer E, Nakasone KK, Redhead SA. (2006) Hymenochaetales: a molecular phylogeny for the hymenochaetoid clade. Mycologia 98: 926–936. 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberta AE. (1960) A taxonomic analysis of section Athele of the genus Corticium. I. Genus Xenasma. Mycologia 52: 884–914. 10.1080/00275514.1960.12024964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SL, Zhao Y, Dai YC, Nakasone KK, He SH. (2017) Phylogeny and taxonomy of Echinodontium and related genera. Mycologia 109: 568–577. 10.1080/00275514.2017.1369830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. (2018) Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.51. http://www.mesquiteproject.org

- Moreno G, Esteve-Raventós F. (2007) A new corticolous species of the genus Tubulicium (Polyporales) from southern Spain. Persoonia 19: 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone KK. (2013) Taxonomy of Epithele (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). Sydowia 65: 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson RH, Tedersoo L, Abarenkov K, Ryberg M, Kristiansson E, et al. (2012) Five simple guidelines for establishing basic authenticity and reliability of newly generated fungal ITS sequences. MycoKeys 4: 37–63. 10.3897/mycokeys.4.3606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ordynets A, Scherf D, Pansegrau F, Denecke J, Lysenko L, Larsson K-H, Langer E. (2018) Short-spored Subulicystidium (Trechisporales, Basidiomycota): high morphological diversity and only partly clear species boundaries. MycoKeys 35: 41–99. 10.3897/mycokeys.35.25678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punugu A, Dunn MT, Welden AL. (1980) The peniophoroid fungi of the West Indies. Mycotaxon 10: 428–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. (2014) FigTree, a graphical viewer of phylogenetic trees. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/fgtree/

- Rambaut A, Drummond A, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard M. (2018) Tracer v1.7. http://beast.community/tracer [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hőhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. (2012) MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology 61: 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2014) RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telleria MT, Melo I, Dueñas M, Larsson KH, Paz Martín MP. (2013a) Molecular analyses confirm Brevicellicium in Trechisporales. IMA Fungus 4: 21–28. 10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.01.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telleria MT, Melo I, Dueñas M, Salcedo I, Beltrán-Tejera E, Rodríguez-Armas JL, Martín MP. (2013b) Sistotremastrumguttuliferum: A new species from the Macaronesian islands. Mycological Progress 12: 687–692. 10.1007/s11557-012-0876-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R, Hester M. (1990) Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. Journal of Bacteriology 172: 4238–4246. 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu D, Groenewald M, de Vries M, Gehrmann T, Stielow B, Eberhardt U, Al-Hatmi A, Groenewald JZ, Cardinali G, Houbraken J, Boekhout T. (2019) Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom Fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Studies in Mycology 92: 135–154. 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee S, Taylor J. (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. (Eds) PCR protocols, a guide to methods and applications.Academic, San Diego, 315–322. 10.1016/b978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [DOI]

- Wu F, Yuan Y, Zhao CL. (2015) Porpomycessubmucidus (Hydnodontaceae, Basidiomycota) from tropical China. Phytotaxa 230: 61–68. 10.11646/phytotaxa.230.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenko E, Wu SH. (2014) Fibrodontiaalba sp. nov. (Basidiomycota) from Taiwan. Mycoscience 55: 336–343. 10.1016/j.myc.2013.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.