Abstract

Purpose

Using a comprehensive flow cytometric panel, do endometrial immune profiles in adverse reproductive outcomes such as repeat implantation failure (RIF) and repeat pregnancy loss (RPL) differ from each other and male-factor controls?

Methods

Six-hundred and twelve patients had an endometrial biopsy to assess the immunophenotype. History on presentation was used to subdivide the population into recurrent implantation failure (RIF) [n = 178], recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) [n = 155], primary infertility [n = 130] and secondary infertility [n = 114]. A control group was utilised for comparative purposes [n = 35] and lymphocyte subpopulations were described.

Results

Distinct lymphocyte percentage differences were noted across the populations. Relative to controls and RPL, patients with a history of RIF had significantly raised uterine NKs (53.2 vs 45.2 & 42.9%, p < 0.0001). All sub-fertile populations had increased percentage peripheral type NKs (p = 0.001), and exhibited increased CD69+ activation (p = 0.005), higher levels of B cells (p < 0.001), elevated CD4:CD8 ratio (p < 0.0001), lower T-regs (p = 0.034) and a higher proportion of Th1+ CD4s (p = 0.001). Patient aetiology confers some distinct findings, RPL; pNK, Bcells and CD4 elevated; RIF; uNK and CD56 raised while CD-8 and NK-T lowered.

Conclusions

Flow cytometric endometrial evaluation has the ability to provide a rapid and objective analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations. The findings show significant variations in cellular proportions of immune cells across the patient categories relative to control tissue. The cell types involved suggest that a potential differential pro-inflammatory bias may exist in patients with a history of adverse reproductive outcomes. Immunological assessment in appropriate populations may provide insight into the underlying aetiology of some cases of reproductive failure.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-018-1300-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Endometrium, ART, Natural killer cells, Lymphocytes, Immunophenotype

Introduction

Implantation failure in an assisted reproductive technology setting, and early pregnancy loss in a more general setting, are relatively commonplace and can be attributed to many causes. Chief among these are chromosomal abnormalities such as embryo aneuploidy [1] [2], with other proposed sources including infection [3], anatomy [4], hormonal [5] and blood clotting disorders; either intrinsic or extrinsic (such as a consequence of antiphospholipid antibodies) [6, 7], altered endometrial receptivity [8, 9] or immune-mediated theories [10, 11]. Next-generation pre-implantation genetic screening techniques (PGT-A) have allowed detailed embryo assessment to be readily incorporated into an IVF cycle in an attempt to control for cytogenetics, but in reality, transfer of screened embryos leads to a live birth in only about half of all cycles [12]. This may be explained, in part, by trophectoderm biopsies as opposed to inner cell mass assessment which gives rise to the possibility of mosaicism contributing to some of these cases. The complex structure of the endometrium encompasses an array of distinct molecules which contribute to cell distribution, adhesion, trafficking and signalling processes, so abnormalities in these areas could also potentially be involved in pregnancy pathology [13], attesting further to the complexity of the implantation and blastocyst development process. Endometrial receptivity itself is another consideration, albeit with abnormalities in the window of implantation appearing in only a small proportion of patients. Lining thickness, trilaminar ultrasonic appearance and recently molecular mRNA cluster evaluations, are regarded as sound markers of receptivity [14, 15], and in combination with PGT-A, can effectively be used to ensure euploid embryos are transferred into a receptive uterus. Despite these interventions, implantation failure and recurrent pregnancy losses still continue to occur in a subset of the population.

Research into immunological variants as possible causative factors of reproductive failure is certainly controversial, particularly when peripheral blood is used, as these cell distribution values are thought to be easily influenced by external dynamics and lack credibility in the wider scientific community [16, 17]. Recent studies, however, have focused more on the endometrial environment, the investigation of which may be more relevant than peripheral blood. There is no argument that the immune system, and in particular the uterine natural killer cells (uNK) and their associated cytokines, play a key role in the implantation process [18]. Immune defects are well recognised in other areas of early pregnancy and placental development. Immunologic maladaptation, for example, has been strongly associated with materno-fetal tolerance morbidities, such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, growth retardation and pre-term birth [19]. The exact process pathways and tolerance abnormalities involved, however, are still not completely understood. Currently, a complete description of the leukocytes in the endometrium, or full uterine immunophenotype, is not well defined. Despite attempts, there is still no fully accepted technique to completely assess the cellular populations present [20], or consensus regarding their interpretation. Timing of the biopsy is also important, as the immune environment changes with the menstrual cycle. Russel et al. demonstrated that uNKs represent only around 5% of stromal cells in the early-mid luteal phase, but increase to ~40% in the late luteal phase [21]. Sample timing and tissue preparation must thus be standardised to achieve meaningful results [22]. Given the relevance of uterine NKs in the process of embryonic implantation and development, they, and their influencers, appear to be a candidate for further investigation when the normal processes fail on a recurrent basis. Endometrial tissue has been subject to varied histologic and immunohistochemical evaluations, and indeed much is known about the developmental changes that occur and the immune populations present [23–25]. Lachapelle et al. demonstrated, in endometrial biopsies as early as 1996, that the patterns of CD4 and CD8 positive T cells can be intrinsically altered in recurrent miscarriage patients, as well as the deleterious presence of B cells and the negative impact of an increase in percentage CD56dim natural killer cells [26]. More recently, differential gene expression patterns have been noted in a small cohort of RIF/RPL patients [27] while deviations in cytokine ratios, specifically IL-15/Fn-14 mRNA as well as IL-I8/TWEAK mRNA have led to a proposal indicating “over activation” as well as “under activation” of the immune cell dialogue may potentially explain the basis of the problem in some cases of RIF [25]. In summary, variations in NK cell populations, expression of specific maternal KIR markers and HLA C genotype (e.g. AA haplotype), as well as T and B lymphocyte variants have all been proposed as having an association with reproductive failure [28–31].

Flow cytometric techniques are easily reproducible, reducing the potential for inter-laboratory variation. Additional benefits include automation of the analytical phase, further increasing reproducibility as well as the ability to analyse very small tissue samples, making it a useful tool when assessing endometrium. Contrarily, tissue samples must be carefully handled in suitable media, be less than 24 to 48 hours old and carefully temperature-controlled to prevent uneven immune cell loss.

Altered uterine immune profiles have been both hypothesised and described [25]. This study aims to add further information to an evolving area, and may help us to understand why chromosomally normal embryos can fail to implant despite a valid receptivity pattern, and why successfully implanted euploid embryos may still end with miscarriage.

Methodology

Six-hundred and twelve patients across three university-affiliated ART centres were assessed over a 3-year period (2014 to 2017). A pilot phase utilising redundant tissue from therapeutic endometrial scratch patients was conducted (commencing 2012) to confirm the reliability, reproducibility and consistency of the tissue preparation and flow cytometry technique. The initial research phase, using a limited array of surface markers, conducted on mid-luteal phase endometrium, proved the concept was viable, accurate and reproducible. A more detailed and complete immunophenotype panel was developed in order to improve the utility and clinical applicability of the test. To develop a large population data set, patients with a poor reproductive history, consisting of either miscarriage or implantation failure were offered an endometrial biopsy to assess the innate lymphocyte populations, in a non-conceptual cycle, in advance of their upcoming treatment. For further subgroup analysis, those patients with strict repeated implantation failure (RIF) and recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) were identified. Inclusion criteria for RIF were defined as > 2 unsuccessful embryo transfers of high-grade blastocysts [32]. RPL was defined as > 2 clinically detectable consecutive or non-consecutive miscarriages [33, 34]. Patients with previous episodes of miscarriage and/or implantation failure, who did not meet the strict RPL/RIF definitions described above were still assessed, but were allocated to primary or secondary infertility groups depending on their previous obstetric history. It should be recognised that these latter subgroups are particularly heterogenous. Putative control biopsies were obtained from females presenting with definitive male factor aetiology, normal-age-related ovarian reserve, and age ≤ 37, attending for ART (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age profile with standard deviation and background obstetric history of the various patient subgroups investigated

| RPL | RIF | P | S | C | All | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 155 | 181 | 127 | 114 | 35 | 612 | |

| Mean age | 38.0 | 37.9 | 36.9 | 37.3 | 35.1 | 37.4 | <0.001 |

| ± SD | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.2 | |

| Mean AMH | 12.6 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 12.6 | 16.3 | 14.2 | 0.575 |

| ± SEM | 1.73 | 1.45 | 2.2 | 1.88 | 2.35 | 9.5 | |

| Total pregnancies | 503 | 18 | 0 | 166 | 16 | 703 | |

| Total live births | 61 | 6 | 0 | 78 | 10 | 155 | |

| Total miscarriages | 442 | 12 | 0 | 88 | 6 | 548 | |

| MR (%) | 87.9 | 66.7 | N/A | 53.0 | 37.5 | 78.0 |

RPL recurrent pregnancy loss, RIF recurrent implantation failure, P primary infertility, S secondary infertility, C control population, MR is the miscarriage rate

In all cases, endometrial tissue was obtained following a standard hormone replacement therapy (HRT) protocol to ensure consistency, with an endometrial biopsy performed after five completed days of vaginally administered progesterone (Crinone 8% ™, Merck pharmaceuticals). This generally corresponded to days 21–24 of the patients’ menstrual cycle, with minor variations in the duration of oral estradiol hemihydrate prior to initiation of a fixed progestogen course, to allow some flexibility when scheduling the biopsy. The tissue sample was transferred into 10 ml RPMI 1640 (Sigma Aldrich UK) and transported to a single laboratory facility, without delay, for analysis and to ensure consistent results. All samples were processed fresh within 24 h of procurement and maintained up to this point at room temperature to avoid differential immune cell loss. The endometrial sample was passed through a 70-μm nylon filter (BD Falcon™, BD Biosciences, UK) to remove it from RPMI and associated blood, blotted and accurately weighed. Samples were standardised to approximately 300 mg of tissue whenever possible. Mechanical dissociation was applied, using Gentle MACs™ C tubes (Milteny Biotech) and 10 ml fresh RPMI to efficiently release all cells, using a preset function (Program C for 30 s, Program B for 30 s) designed as suitable for endometrial tissue. The Gentle MACs™ system is a proven and effective technology to completely dissociate cells from one another allowing subsequent full cellular evaluation. Enzymatic degradation/digestion with collagenase was avoided to prevent possible changes in expression of cell surface markers. The free cell lysate was then passed through a 40-μm nylon filter to isolate connective tissue elements above this size, pelleted at ×500 g, and re-suspended to a final volume of 1.5 ml in BD staining buffer (BD Biosciences, UK). Two-hundred microliters of resuspended cells was then incubated with the antibody cocktails described below. The antibody cocktails were standardised to a final volume of 100 μl with BD staining buffer. Flow cytometric evaluation followed using co-localisation of these specific antibodies by multicolour/multitube flow cytometry (Navios™, Beckman Coulter UK LTD).

Tube 1 (NK tube); CD45 (KO), CD3 (pacific blue), CD5 (APC-AF700), CD16 (ECD), CD56 (PE), CD57 (FITC), CD69 (APC), CD19 (PC5.5)

Tube 2 (T cell tube); CD45 (KO), CD3 (pacific blue), CD4 (APC-AF750), CD8 (ECD), CD25 (APC), CD127 (FITC), CD183 (PC), CD196 (PC7)

Cytometer voltage and gain settings are available in Supplementary data 1.

The antibody/re-suspended cell cocktail was incubated at RT in the dark for 20 min and lysed for 10 min to eliminate RBC contamination with 900 μl Versalyse™ solution (Beckman Coulter UK Ltd.). Analysis followed the addition of 100 μl flow count beads™ (Beckman Coulter UK Ltd.). The cytometer manufacturer’s expertise was utilised to design the ten colour flow panel and appropriate compensation matrices. Following completion of the initial pilot study, an assessment was made for dead cell discrimination prior to commencing prospective data collection. 7-AAD viability dye demonstrated the position of dead cells and these regions did not correspond to the lymph gate after 24 or 48 h delay, confirming that non-viable cells which may non-specifically bind antibodies were excluded from the analysis (Supplemental 2).

Tube 1 allowed detailed evaluation of uterine/decidual type natural killer cells (uNK;CD3-, CD16-, CD56 bright), peripheral type natural killer cells (pNK: CD16+, CD56dim) with expression of the activation marker CD69, natural killer T cells (NKT; CD3+, CD16-, CD56dim), the overall expression of CD57+ (NK maturity marker) within the pNK and NK-T populations and finally B cell expression (CD19+). CD5+ was also utilised for uNK gating in order to confirm minimal contamination of the CD56 bright region with CD5+ T cells [35]. The uNK gate was also set to not include CD56dim moieties as these have strong CD3+ and CD5+ representation and correspond to the majority of the CD56dim CD3+, NK-Ts (Fig. 2). Tube 2 employed some similar fluorophores but associated with different CD markers and allowed evaluation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, T regulatory cells (CD4+,CD127low, CD25high), Th1 cells (CD4+, CD183+, CD196-), Th17 cells (CD4+, CD183-, CD196+) and Th2 cells (CD4+, CD183-, CD196-). Percentages are relative to CD45+ lymphocytes, except total CD56, CD4+ subsets and CD69. No additional data processing software was utilised for analysis of results. Advanced approval was obtained from the clinic’s institutional review board while informed consent was obtained from patients for the biopsy procedure and subsequent analysis. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. IBM SPSS v24 was employed for statistical analysis. Using skewness-kurtosis plots, it was determined that the population data was not normally distributed for the majority of parameters, so medians and centiles were selected as the most representative statistics (Table 2). Non-parametric analysis (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U) was used to look for differences between groups.

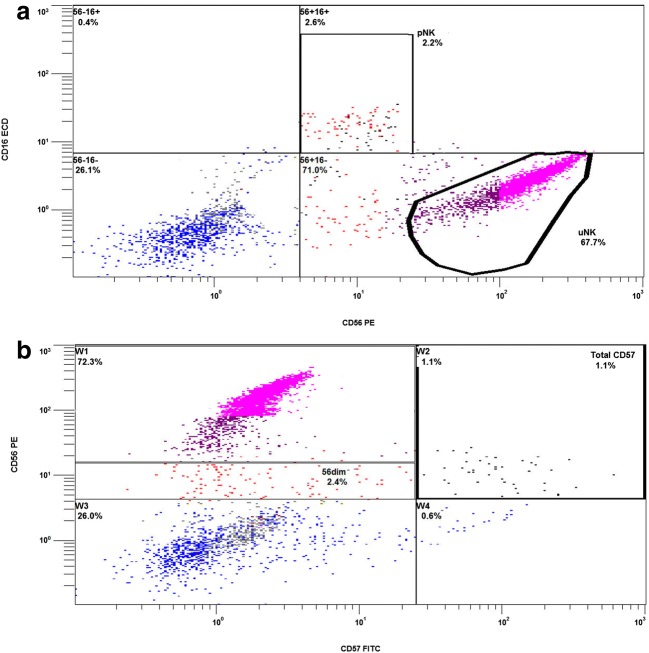

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometry illustration indicating the uterine natural killer cells as the dominant lymphocyte (A) and expression of other markers which allow discrimination of NK subpopulations; CD16+ CD56dim (pNK). NK-T are not illustrated here directly as CD3 or CD5 are not utilised on these channels, but can be seen below pNK and to the left of uNK. Panel (B) in the same patient illustrates CD57 expression and the localisation of this marker to CD56dimcells alone

Table 2.

Total population endometrial biopsy immunophenotype lymphocyte proportions (expressed as a % of total CD45+ leucocytes), with statistical percentages shown as average, median, and centiles. Lymph % is the % of CD45+ lymphocytes relative to the total biopsy cell population (stromal, endothelial, epithelial, polymorphonuclear, etc.). Similarly, CD56 (TOTAL) is the % of cells in the entire biopsy expressing CD56 (see also Fig. 1B). All other percentage values are relative to the CD45+ lymph population except activated pNK which refers to the proportion of pNKs which are expressing CD69 and the various CD4+ subpopulations which are relative to CD4+ only

| Natural killer cells | T lymphocytes | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ subsets | |||||||||||||||||

| BX weight | Lymphs % | CD56 (total) | uNK | NKT | pNK | Activated pNK | Total CD57 | B-cells | CD8+ | CD4+ | T reg | Th1 | Th17+ | Th2 | Th1 to Th2 ratio | CD4 to CD8 ratio | |

| Mean | 0.3 | 8.0 | 4.9 | 44.5 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 17.6 | 12.1 | 5.7 | 66.9 | 2.6 | 9.7 | 17.3 | 0.8 |

| Median | 0.3 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 45.2 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 13.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 16.2 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 72.5 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 12.0 | 0.7 |

| 5th centile | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 13.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| 95th centile | 0.5 | 19.7 | 13.0 | 72.1 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 83.3 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 34.6 | 24.7 | 14.6 | 88.5 | 9.3 | 33.3 | 57.4 | 1.7 |

Results

Five-hundred and seventy-seven recruited patients and 35 putative controls underwent a HRT primed biopsy and endometrial immunophenotype analysis during the study period. A detailed evaluation of their prior reproductive history revealed that 181 patients had repeated implantation failure at presentation, 155 had a background of recurrent pregnancy loss, 127 patients presented with primary infertility and 114 with secondary infertility. There were no significant differences in AMH levels between groups; however, a marked variation in age was noted, with controls being younger (35.1 years) and RPL patients oldest (38.0 years, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Using flow cytometric side scatter and gating strategies described above, lymphocytes could be clearly differentiated from the other cells present within the biopsy (Fig. 1A). The natural killer cells (NKs) could be further differentiated into three distinct populations (Fig. 2 & Table 2). The most abundant lymphocytes were the resident uterine/decidual type, or uNK (CD16-, CD56bright), indicating their immature status and most likely local stem cell origins, as opposed to systemic recruitment. The remaining NKs were either peripheral type, (pNK; CD3−, CD16+, CD56dim) or T cell type, (NK-T; CD3+, CD16−, CD56dim), with the latter two populations being rarer and sometimes also co-expressing the classical maturity marker CD57 (Fig. 2B). CD4 and CD8 including various CD4+ subpopulations were also differentiated (Fig. 3 & Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry image illustrating the selection of the lymphocyte gate using side scatter and antibodies to CD45. Lower panel (B) illustrates the total percentage expression of CD56 relative to all cells present in the biopsy

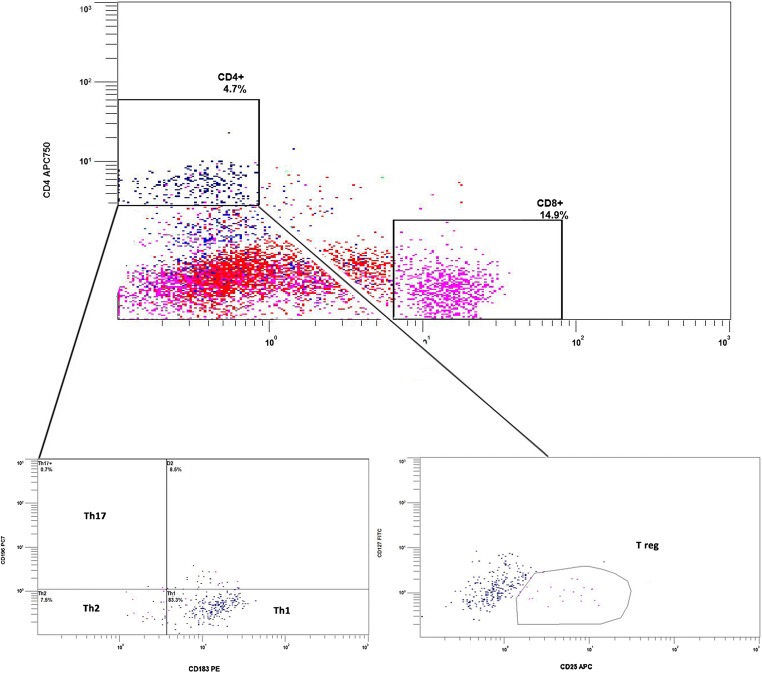

Fig. 3.

Top panel illustrating all lymphocytes with specific isolation of CD4+ and CD8+ cells. The lower panel shows further differentiation of CD4+ cells into various bioactive subtypes, Th1, Th2, and T reg specifically. Positive CD3 staining is used to effectively set the CD4 and CD8 gates as it eliminates all the other non-T cell lymphocytes from the view. In the example below lymph gating, showing all available lymphocytes, rather than CD3+ gating is utilized

Interestingly, distinct lymphocyte subpopulation differences were noted between subgroups, with specific aetiologies showing particular patterns (Table 3 & Fig. 4). A marker which was elevated in all adverse outcome populations compared to the controls were peripheral type NK cells (pNK), identifying this as a possible marker of endometrial dysfunction. The pNKs in the adverse outcome cases also demonstrated considerably higher levels of pNK CD69+ activation compared to controls (p = 0.005). T lymphocyte differences were evident, and may also be important discriminators. T cells expressing CD4 and CD8 were seen in varying degrees in all cases, but invariably the CD4:CD8 ratio (control median 0.48) was inverse to that typically seen in peripheral blood (~ 2:1). The CD4+ lymphocytes can be further subdivided into T regulatory, Th1, Th17 and Th2 subtypes (Table 2 & Fig. 3). Total endometrial CD56 expression was also evaluated, giving the proportion of CD56+ cells relative to all cells within the biopsy (Fig. 1B), and again significant differences were observed between the groups (p = 0.034). Additionally, B cell evaluation using CD19 revealed statistically significant increases in percentage expression between the studied groups and controls (p < 0.001, Table 3).

Table 3.

Median percentage distribution of immunological subtypes, across the patient groups, as a proportion of total CD45+ endometrial lymphocytes. Activated pNK subtype percentages are relative to pNK cells only. CD4+ subtype percentages are relative to CD4+ cells only. Total CD56 is the proportion of CD56+ cells relative to the entire biopsy cellular population (e.g., stromal, endothelial, epithelial, polymorphonuclear). P values determined using Kruskal Wallis test (SPSS v24)

| Cell Type | Controls (%) | RPL (%) | RIF (%) | Primary (%) | Secondary (%) | p value (overall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lymphocytes | 6.08 | 7.06 | 7.46 | 6.73 | 6.47 | 0.227 |

| pNK | 0.7 | 1.24 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.21 | 0.001* |

| -Activated pNK | 5.76 | 15.22 | 14.8 | 12.5 | 12.69 | 0.005* |

| NK-T | 2.3 | 2.68 | 2.2 | 3.01 | 3 | 0.001* |

| uNK | 45.2 | 42.92 | 53.24 | 41.38 | 38.71 | < 0.0001* |

| CD57 | 0.3 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.127 |

| B-cells | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 0.8 | < 0.001* |

| CD8+ | 15.86 | 17.15 | 13.34 | 17.07 | 17.96 | < 0.001* |

| CD4+ | 8.35 | 10.67 | 9.42 | 12.79 | 12.21 | < 0.001* |

| -T Reg | 5.3 | 3.81 | 4.32 | 3.76 | 3.29 | 0.034* |

| -Th1 | 65 | 72.89 | 74.07 | 73.57 | 72.96 | 0.001* |

| -Th2 | 9.47 | 6.21 | 5.7 | 4.17 | 4.95 | 0.059 |

| -Th17 | 1.85 | 1.34 | 1.45 | 1.23 | 1.46 | 0.572 |

| Total CD56 | 3.33 | 3.56 | 4.38 | 3.98 | 3.04 | 0.003* |

| Th1:Th2 ratio | 6.05 | 10.75 | 12.01 | 15.68 | 12.33 | 0.012* |

| CD4:CD8 ratio | 0.48 | 0.7 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.71 | < 0.0001* |

Values in bold and with asterix* are statistically significant being less than p=0.05

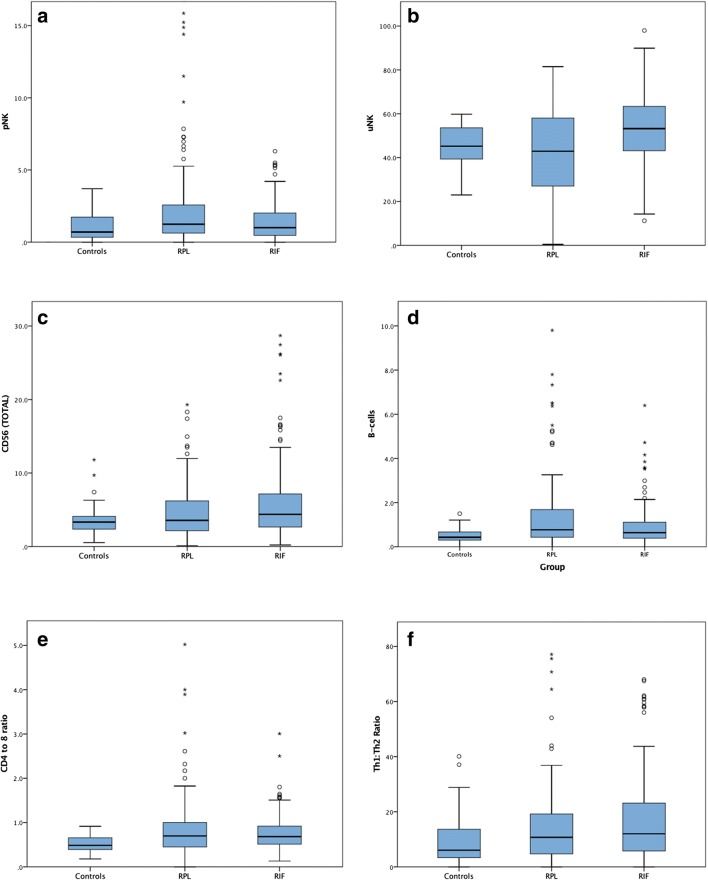

Fig. 4.

Box and whisker plots illustrating the relative percentage spread of the two main patient population investigated, RIF and RPL versus that of the controls a pNK, b uNK, c CD56 total, d B-cells, e CD4 to 8 ratio and f Th1 to Th2 ratio

Cellular markers of interest in the RPL cases are pNKs, B cells and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Significantly higher percentage levels of these markers are exhibited in recurrent miscarriage patients compared to both control and implantation failure groups (Table 4). For RIF patients, the lymphocyte populations with significant differences were uNKs, total CD56 (both increased), NK-Ts and CD8 (both decreased). Patients with RIF but not RPL had significantly raised levels of uterine NKs (median 53.2% versus 45.2%, p < 0.0001). The RPL group in particular displayed significant uNK heterogeneity and contains significant numbers of patient outliers both above and below the normal range (Mean ± 2SD), compared to the RIF group which was typically found at the upper end of the scale (Fig. 4). Higher percentage expression of CD4+ T cells was seen across the subgroups relative to control tissue (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Across all of the abnormal populations, Th1 expression, Th1:2 ratio and CD4:8 ratio were significantly increased. Cells representing the T regulatory subset were significantly lower in all abnormal groups compared to controls (p = 0.034). Percentage expression of CD8+ T cells on the other hand were increased in RPL, primary and secondary groups but found to be decreased in the RIF population (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of statistically significant differences (p values) across the patient subpopulations, relative to controls and each other. Significance levels determined with Mann Whitney U test, using distribution around the median (SPSS v24)

| Cell type | RPL vs control | RIF vs control | RPL vs RIF | Primary vs secondary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lymphocytes | 0.185 | 0.262 | 0.579 | 0.520 |

| pNK | 0.008* | 0.006* | 0.013* | 0.036* |

| -Activated pNK | 0.001* | 0.001* | 0.475 | 0.950 |

| NK-T | 0.104 | 0.001* | < 0.0001* | 0.530 |

| uNK | 0.386 | < 0.0001* | < 0.0001* | 0.480 |

| CD57 | 0.110 | 0.200 | 0.181 | 0.421 |

| B-cells | < 0.001* | < 0.0001* | 0.010* | 0.301 |

| CD8+ | 0.727 | 0.003 | 0.003* | 0.599 |

| CD4+ | 0.012* | 0.005 | 0.006* | 0.982 |

| -T Reg | 0.170 | 0.239 | 0.182 | 0.144 |

| -Th1 | 0.001* | < 0.0001 | 0.212 | 0.772 |

| -Th2 | 0.450 | 0.490 | 0.605 | 0.336 |

| -Th17 | 0.578 | 0.827 | 0.901 | 0.548 |

| Total CD56 | 0.645 | 0.036 | 0.024* | 0.035* |

| Th1:Th2 ratio | 0.080* | 0.023* | 0.191 | 0.314 |

| CD4:CD8 ratio | 0.001* | 0.001* | 0.827 | 0.629 |

Values in bold and with asterix* are statistically significant being less than p=0.05

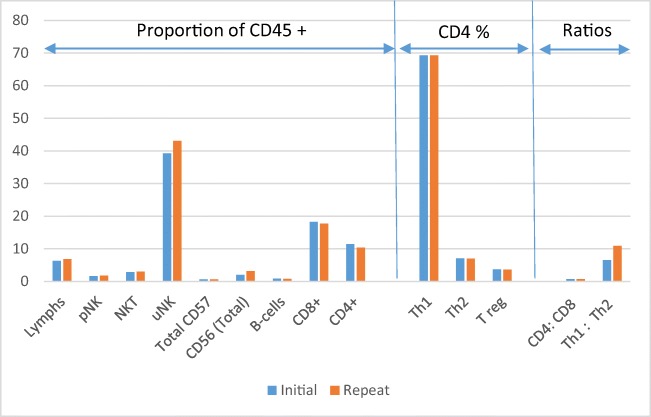

In order to assess technique consistency, 41 individuals had repeat biopsies performed following an unsuccessful ART cycle, and within a 4–8-month interval of the initial sample. This time scale was chosen to minimise any impact from confounding factors, such as immunomodulatory effects of the original scratch/biopsy or luteal phase support medications. No statistical difference in immune profiles was observed compared to the original sample using both paired and non-parametric testing, indicating technique reproducibility, reagent and immunophenotype consistency across cycles (Fig. 5 & Supplemental 3).

Fig. 5.

Median percentage expression of immune cell subtypes between the first and repeat biopsy in 41 individuals. Mann Whitney U t-test shows no significant differences between paired samples

Discussion

Endometrial immune cell populations, detailed analysis of subtypes, along with determination of centile values for abnormal cases and controls, have been described in depth. The patients analysed, had poor reproductive history, with repeated episodes of pregnancy loss or implantation failure, often with a background of prolonged infertility. Differences were clearly observed in distribution patterns relative to control samples but it is not clear which of these immunological aspects could play a dominant role in either implantation failure or early pregnancy loss. The myriad mechanisms involved in the successful implantation and development of an embryo are well understood, but less is known about correlation between potential immune dysfunction and clinical outcome. A hypothesis derived from this study, based on the distribution of the immunophenotype between groups, may be that in patients with a history of adverse reproductive outcomes such as RIF/RPL, differing immune mechanisms may in fact be in play which could ultimately affect the result, some local and some systemic. The uterine NK cell population has undoubtedly been shown to play a key role in the implantation and placentation process. However, we show that increased expansion of this cellular population is strongly associated with repeated implantation failure during traditional ART cycles. Varied explanations for this local change may be considered; it could be that the uNKs may not be limited in their toxicity as is the normal scenario [36] or the expansion of the uNK population is in response to an as yet unknown stimulus. Recent work indicates that human herpes virus 6a (HHV6a) may accentuate uNK cell percentages and has been demonstrated to have a strong association with implantation failure in particular [37, 38]. While recognised as being more immature and less cytotoxic, the CD56bright uNKs are important immune regulators and have use of varied cytokines, including IFNg and TNFa. Although cytotoxicity changes are known to also potentially occur in cases of uterine CMV infection, this process has not yet been demonstrated against a healthy embryo [39], but our findings raise this possibility. A further explanation for increased uNK toxicity could be an increase in activating KIR haplotypes [31], perhaps left over as a response to previously failed non-compatible pregnancies. Natural killer cells are also known to influence T cells and vice versa [40], certainly the local production of TNFa and IFNg will influence their cytotoxicity profile [41]. It is possible that the cytokine milieu, and a potential bias towards pro-inflammatory cytokines, as seen in the CD4+ Th1 shift, could be a destructive agent in these cases, with embryo loss as a bystander effect. Further work examining specific NKp receptors (for example NKp-30, 44 and 46), their response to local cytokines and their role in activation and inhibition of the NK cells, may well be informative in this regard.

CD56+ cells represent the natural killer cell phenotype in general but can be further differentiated into CD56bright or CD56dim. These populations have quite different cytotoxicity profiles. Uterine natural killer cells are exclusively CD56bright while peripheral natural killer cells express CD16 and are exclusively CD56dim. Although not demonstrated here, lower levels of uNK CD56bright have also been associated with reproductive failure [42]. The RPL uNK percentage population we observed can be lower than that of controls in some cases, perhaps corroborating this finding. Populations of peripheral blood “type” natural killer cells were identified in the endometrium of both controls and RPL/RIF patients despite careful tissue preparation to avoid contamination with peripheral blood. The relative expression of these cells increased in our study populations. Cells with these characteristics, by virtue of the CD56dim profile, are recognised as being more mature with high cytotoxic potential [43], and may also co-express CD57. It is likely that these cells are recruited from peripheral blood, and potentially are associated with the endometrial microvasculature as opposed to tissue resident as is the case with uNKs. The CD57 maturity marker would appear to corroborate this origin theory as it is unlikely the maturation phases to CD57 positive could be accomplished in one menstrual cycle. The lack of CD56dim and CD57 on uterine NKs also points strongly to their local origin. Why more “peripheral type” NKs are present in these patient groups is unknown. Theories that could be investigated further may include association with high peripheral blood concentrations, defective gap junctions facilitating migration, or potentially a local phenotypic switch of some cells from uNK to pNK under environmental pressure such as a viral or bacterial presence or imbalance.

Higher levels of endometrial CD4+ cells, or perhaps more specifically, the associated pro-inflammatory subgroups, may be a predictive marker of a hostile uterus. Surface marker expression was used to subdivide CD4+ T cells into various active subtypes, namely Th1, Th2, Th17 and T-regulatory. The uterine microenvironment appears unique in that the CD4+ T cell population are predominantly the Th1 phenotype, typically associated with a pro-inflammatory type response. Unpublished observations suggest peripheral blood is the polar opposite, with Th2 type being dominant. Another variation compared to peripheral blood is the dominance of CD8+ T cells over CD4+, with CD4+ lymphocytes being present in a ratio of 0.7. More extreme changes of this ratio, primarily by an increase of CD4, are associated with negative outcomes such as RIF and RPL. Raised CD4+ levels may be particularly prognostic of RPL. If the origin of these T cells is from peripheral blood rather than de novo development locally, this may point to non-genetic “unexplained” RPL as a more systemic than endometrial problem. Raised peripheral type NKs and B cells, again most likely originating from the peripheral circulation may support this theory. Regulatory T-cells are arguably of utmost importance in this milieu of cells and are primarily responsible for mediating the shift from a Th1 dominant to a Th2 dominant phenotype with the advent of an implanted embryo. This study uses flow cytometry for the first time to delineate the normal endometrial T-regulatory population, and their variation between subgroups.

Recent studies have used molecular techniques to investigate the ratios between IL-15/Fn-14 mRNA as a biomarker of uNK cell activation/maturation as well as IL-18/TWEAK mRNA ratio as a surrogate marker of Th1/Th1 balance [25]. This technique, not dependent upon fresh tissue, has shown an imbalance in these ratios in over 80% of RIF patients. The investigators go further and in fact describe both underactive (25%) and overactive profiles (56.6%) in their patient cohort and recommend differing treatment modalities to address the imbalances observed. This study supports the idea of an underactive immune system in some cases, particularly in the RPL group, which has significant numbers of patient outliers both above and below the normal range seen in controls. The presence of B cells in the endometrium has also been noted to have an association with RPL [26]. This study confirms the potential importance of the presence of B cells in the pathology of RIF/RPL. The Th2 shift expected to occur following successful implantation is thought to favour B cell responses over that of T cells, perhaps heralding the development of NK blocking antibodies and maternal immunosuppression. Elevated B cells prior to this event may operate antagonistically to this process.

Gleicher suggests that maternal immunological tolerance of the fetus is a process of sequential steps of tolerance development, allowing for acceptance of a rapidly growing and immunologically differing paternal semi allograft [44]. Potentially, some RPL cases may be associated with insufficiency in the development of systemic tolerance pathways, which could result in the maternal immune system continuing to regard the fetus as foreign, mounting an abnormal allogenic immune response against it. Conversely, RIF may represent increased local hostility directly in the endometrium such as found in chronic endometritis.

Immunotherapy for implantation failure or miscarriage is a controversial strategy, with a lack of strong evidence to support its routine use [45]. A common theme to many of these investigations is poor study design and patient selection which perhaps underpowers the work to show a significant impact of therapy on outcomes such as live birth [46] or adds potential bias during patient selection. A targeted endometrial assessment, however, such as that described here could be used to better identify patient subgroups with poor reproductive histories. This specific group of patients could benefit to a greater degree from targeted immunotherapy [47]. Further studies on selected patients, to assess if specific immunotherapy, personalised to the individual endometrial immunophenotype, could have a beneficial role in their successful treatment, or, if as is suggested in some quarters that there is no clear benefit in these types of interventions. An intriguing explanation for this apparent dichotomy may now be found in the fact that not all RIF individuals, perhaps little more than 50%, will physiologically respond to corticosteroids as expected [48]. Although, this may be a patient classification issue as much as an irregular response to therapy.

A potential benefit of this test, in the implantation failure subgroup in particular, is that it also elicits an endometrial injury, often referred to as a “scratch” and hypothesised to improve implantation in those patients in which this is a potential issue [49, 50]. The mechanical abrasion followed by wound healing may positively influence implantation rates by triggering the release of cytokines, chemokines, IL-15, adhesion molecules, growth factors and hormones. It is also hypothesised to potentially switch on or transiently activate dormant genes [51, 52]. The procedure itself and the subsequent biologic response is uncertain, however, potentially improved receptivity in a proportion of these patients, as well as simultaneous assessment of the local immune environment may yield further useful information on patient categorisation and associated immune profiles. Patients presenting with under-active immune profiles for instance may well benefit from this approach to the greatest extent and perhaps this patient group should be specifically targeted for evaluation. As PGT-A becomes more utilised, there is the potential need for in fact more detailed assessments of endometrial function, if and when, euploid embryos do not lead to an ongoing pregnancy [12]. Molecular assessments of receptivity are also becoming more widely accepted, personalising luteal support regimes to optimise timing of embryo transfer with the window of implantation. With time and further study, it is possible that a more detailed immunological assessment of the endometrium may also have a prognostic role, and sit side by side with these evaluations, tailoring therapeutic interventions to individual patient status, in order to optimise the uterine environment to receive an embryo and lead to a healthy pregnancy.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 635 kb)

Co-localisation of CD45 lymphocytes with 7-AAD illustrating only live endometrial derived cells are analysed in the lymphocytes gate. (JPG 460 kb)

(DOCX 13 kb)

(DOCX 33 kb)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Sims IVF patients who contributed tissue samples to facilitate the analysis and the Staff of the Clinic for their support. Thanks also to Dr. Renate Van der Molen, UMC Radboud, for critical appraisal of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- PGT-A

preimplantation genetic analysis-aneuploidy

- RPL

recurrent pregnancy loss

- RM

recurrent miscarriage

- RIF

repeat implantation failure

- ART

assisted reproductive technologies

- HRT

hormone replacement therapy

- uNK

uterine type natural killer cells

- pNK

peripheral blood type natural killer cells

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- Th1

T helper type 1 (pro-inflammatory)

- Th2

T helper type 2 (anti-inflammatory)

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest is present.

References

- 1.Lathi RB, Westphal LM, Milki AA. Aneuploidy in the miscarriages of infertile women and the potential benefit of preimplanation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Hachem H, et al. Recurrent pregnancy loss: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:331–345. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S100817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giakoumelou S, Wheelhouse N, Cuschieri K, Entrican G, Howie SEM, Horne AW. The role of infection in miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(1):116–133. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozdag G, Aksan G, Esinler I, Yarali H. What is the role of office hysteroscopy in women with failed IVF cycles? Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;17(3):410–415. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60226-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riccio L, et al. Immunology of endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;50:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern C, Chamley L. Antiphospholipid antibodies and coagulation defects in women with implantation failure after IVF and recurrent miscarriage. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Simone N, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies affect human endometrial angiogenesis: protective effect of a synthetic peptide (TIFI) mimicking the phospholipid binding site of beta(2) glycoprotein I. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70(4):299–308. doi: 10.1111/aji.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgain C, Devroey P. The endometrium in stimulated cycles for IVF. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9(6):515–522. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revel A. Defective endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(5):1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwak-Kim J, Bao S, Lee SK, Kim JW, Gilman-Sachs A. Immunological modes of pregnancy loss: inflammation, immune effectors, and stress. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(2):129–140. doi: 10.1111/aji.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill JA. Immunological contributions to recurrent pregnancy loss. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;6(3):489–505. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3552(05)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franasiak JM, Scott RT. Contribution of immunology to implantation failure of euploid embryos. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1279–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas ES, Dyer NP, Murakami K, Hou Lee Y, Chan YW, Grimaldi G, Muter J, Brighton PJ, Moore JD, Patel G, Chan JKY, Takeda S, Lam EWF, Quenby S, Ott S, Brosens JJ. Loss of endometrial plasticity in recurrent pregnancy loss. Stem Cells. 2016;34(2):346–356. doi: 10.1002/stem.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steer CV, Campbell S, Tan SL, Crayford T, Mills C, Mason BA, Collins WP. The use of transvaginal color flow imaging after in vitro fertilization to identify optimum uterine conditions before embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1992;57(2):372–376. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz-Gimeno P, et al. A genomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moffett A, Shreeve N. Reply: first do no harm: continuing the uterine NK cell debate. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(1):218–219. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maecker HT, McCoy JP, Nussenblatt R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the human immunology project. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(3):191–200. doi: 10.1038/nri3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Mourik MS, Macklon NS, Heijnen CJ. Embryonic implantation: cytokines, adhesion molecules, and immune cells in establishing an implantation environment. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(1):4–19. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savasi VM, Mandia L, Laoreti A, Cetin I. Maternal and fetal outcomes in oocyte donation pregnancies. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(5):620–633. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang AW, Alfirevic Z, Quenby S. Natural killer cells and pregnancy outcomes in women with recurrent miscarriage and infertility: a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(8):1971–1980. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell P, Sacks G, Tremellen K, Gee A. The distribution of immune cells and macrophages in the endometrium of women with recurrent reproductive failure. III: further observations and reference ranges. Pathology. 2013;45(4):393–401. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e328361429b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laird, L., Li, Bulmer, <RCOG 2016 guidelines.pdf>. 2016.

- 23.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, Gazit R, Yutkin V, Benharroch D, Porgador A, Keshet E, Yagel S, Mandelboim O. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12(9):1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loke YW, King A, Burrows TD. Decidua in human implantation. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.suppl_2.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lédée N, Petitbarat M, Chevrier L, Vitoux D, Vezmar K, Rahmati M, Dubanchet S, Gahéry H, Bensussan A, Chaouat G. The uterine immune profile may help women with repeated unexplained embryo implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75(3):388–401. doi: 10.1111/aji.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lachapelle MH, et al. Endometrial T, B, and NK cells in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Altered profile and pregnancy outcome. J Immunol. 1996;156(10):4027–4034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledee N, et al. Specific and extensive endometrial deregulation is present before conception in IVF/ICSI repeated implantation failures (IF) or recurrent miscarriages. J Pathol. 2011;225(4):554–564. doi: 10.1002/path.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moffett A, Colucci F. Uterine NK cells: active regulators at the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):1872–1879. doi: 10.1172/JCI68107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quenby S, Farquharson R. Uterine natural killer cells, implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vassiliadou N, Bulmer JN. Immunohistochemical evidence for increased numbers of ‘classic’ CD57+ natural killer cells in the endometrium of women suffering spontaneous early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(7):1569–1574. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alecsandru D, Garcia-Velasco JA. Why natural killer cells are not enough: a further understanding of killer immunoglobulin-like receptor and human leukocyte antigen. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1273–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laufer N, Simon A. Recurrent implantation failure: current update and clinical approach to an ongoing challenge. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(5):1019–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medicine, T.P.C.o.t.A.S.f.R., Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility, 2012. 98(5): p. 1103–1111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.ESHRE, <ESHRE RPL Guideline_28112017_FINAL.pdf>. 2017.

- 35.Burkhard SH, Mair F, Nussbaum K, Hasler S, Becher B. T cell contamination in flow cytometry gating approaches for analysis of innate lymphoid cells. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dosiou C, Giudice LC. Natural killer cells in pregnancy and recurrent pregnancy loss: endocrine and immunologic perspectives. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(1):44–62. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marci R, Gentili V, Bortolotti D, Lo Monte G, Caselli E, Bolzani S, Rotola A, di Luca D, Rizzo R. Presence of HHV-6A in endometrial epithelial cells from women with primary unexplained infertility. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coulam CB, Bilal M, Salazar Garcia MD, Katukurundage D, Elazzamy H, Fernandez EF, Kwak-Kim J, Beaman K, Dambaeva SV. Prevalence of HHV-6 in endometrium from women with recurrent implantation failure. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e12862. doi: 10.1111/aji.12862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siewiera J, el Costa H, Tabiasco J, Berrebi A, Cartron G, Bouteiller P, Jabrane-Ferrat N. Human cytomegalovirus infection elicits new decidual natural killer cell effector functions. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(4):e1003257. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fehniger TA, Cooper MA, Nuovo GJ, Cella M, Facchetti F, Colonna M, Caligiuri MA. CD56bright natural killer cells are present in human lymph nodes and are activated by T cell-derived IL-2: a potential new link between adaptive and innate immunity. Blood. 2003;101(8):3052–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petitbarat M, Rahmati M, Sérazin V, Dubanchet S, Morvan C, Wainer R, de Mazancourt P, Chaouat G, Foidart JM, Munaut C, Lédée N. TWEAK appears as a modulator of endometrial IL-18 related cytotoxic activity of uterine natural killers. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukui A, Funamizu A, Yokota M, Yamada K, Nakamua R, Fukuhara R, Kimura H, Mizunuma H. Uterine and circulating natural killer cells and their roles in women with recurrent pregnancy loss, implantation failure and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;90(1):105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiruchelvam U, Wingfield M, O'Farrelly C. Natural killer cells: key players in endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;74(4):291–301. doi: 10.1111/aji.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gleicher N. Expected advances in human fertility treatments and their likely translational consequences. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hviid MM, Macklon N. Immune modulation treatments—where is the evidence? Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alecsandru D, Garcia-Velasco JA. Immune testing and treatment: still an open debate. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(8):1994. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks G. Enough! Stop the arguments and get on with the science of natural killer cell testing. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(7):1526–1531. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ledee N, et al. Impact of prednisone in patients with repeated embryo implantation failures: beneficial or deleterious? J Reprod Immunol. 2018;127:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Potdar N, Gelbaya T, Nardo LG. Endometrial injury to overcome recurrent embryo implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2012;25(6):561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Aldo PB, Barash A, Or Y, Schechtman E, Mor G, Dekel N. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2030–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nastri, C.O., et al., Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(3): p. Cd009517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Reljic M, et al. Endometrial injury, the quality of embryos, and blastocyst transfer are the most important prognostic factors for in vitro fertilization success after previous repeated unsuccessful attempts. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(6):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0916-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 635 kb)

Co-localisation of CD45 lymphocytes with 7-AAD illustrating only live endometrial derived cells are analysed in the lymphocytes gate. (JPG 460 kb)

(DOCX 13 kb)

(DOCX 33 kb)