Abstract

In this study, we integrate data from field investigations, spatial analysis, genetic analysis, and Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) to evaluate the effects of habitat fragmentation on the population dynamics, genetic diversity, and range shifts in the endangered Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti). The results indicate that from 1994 to 2016, R. bieti population size increased from less than 2,000 to approximately 3,000 individuals. A primary factor promoting population recovery was the establishment of protected nature reserves. We also found that subpopulation growth rates were uneven, with the groups in some areas, and the formation of new groups. Both the fragmentation index, defined as the ratio of the number of forest patches to the total area of forest patches (e.g., increased fragmentation), and increasing human population size had a negative effect on population growth in R. bieti. We recommend that government conservation plans prioritize the protection of particular R. bieti populations, such as the Baimei and Jisichang populations, which have uncommon haplotypes. In addition, effective conservation strategies need to include an expansion of migration corridors to enable individuals from larger populations such as Guyoulong (Guilong) to serve as a source population to increase the genetic diversity of smaller R. bieti subpopulations. We argue that policies designed to protect endangered primates should not focus solely on total population size but also need to determine the amount of genetic diversity present across different subpopulations and use this information as a measure of the effectiveness of current conservation policies and the basis for new conservation policies.

Keywords: Habitat fragmentation, Human disturbance, Rhinopithecus bieti, Population size, Conservation policies, Spatial analyst, Range shift, Human population density, Genetic diversity, Land use

Introduction

Globally, anthropogenic activities resulting in deforestation, habitat loss, the extraction of natural resources, the introduction of invasive species, agricultural expansion, and climate change represent a major driver of the unprecedented decline in biodiversity (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2006; Magurran & Dornelas, 2010; Newbold et al., 2015). Quantifying the effects of individual factors and developing solutions to protect environments and endangered is a key scientific challenge (Mace et al., 2010; Magurran & Dornelas, 2010). Anthropogenic activities have altered as much as 50% of terrestrial land cover, and land-use patterns, such as the expansion of croplands for industrial agriculture and pastures for grazing cattle and other domesticated animals, has led to a global reduction in the number of species (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2006; McGill, 2015). This has led scientists to refer to the current period as the Anthropocene mass extinction event (Ceballos, Ehrlich & Dirzo, 2017), with species extinction rates estimated to be 100–1,000 times greater than during past evolutionary periods (Raup, 1995; Pimm et al., 1995). Protecting animal and plant survivorship ad biodiversity requires monitoring and managing changes in species population size and genetic diversity (Dornelas et al., 2014).

An important form of habitat degradation is fragmentation, which transforms large tracts of continuous habitat into smaller and spatially distinct patches immersed within a dissimilar matrix (Didham, Kapos & Ewers, 2012; Wilson et al., 2016). Fragmentation can create detrimental edge affects along the boundaries of habitat patches, alter ecological conditions resulting in the decline of native species, restrict animal movement and gene flow, and sever landscape connectivity (Crooks & Sanjayan, 2006) leading to local population extinction in response to insufficient viable “core” habitat (Ewers & Didham, 2007). Habitat fragmentation has continued at an alarming rate, and has impaired key ecosystem functions by decreasing biomass, limiting seed dispersal, shifting predator-prey relationships, and altering nutrient cycles (Haddad et al., 2015).

Several species of nonhuman primates are particularly affected by habitat fragmentation due to their dependence on intact and biodiverse forested landscapes to obtain a nutritionally balanced diet (Arroyo-Rodríguez & Fahrig, 2014). Currently, anthropogenic habitat modifications have resulted in more than half of the world’s primate species listed as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered (Estrada et al., 2017, 2018). Primate populations inhabiting small and isolated forest fragments are especially vulnerable to extinction (Benchimol & Peres, 2013). However, given evidence of behavioral plasticity, the benefits of social learning, and the ability to exploit a broad range of different food types, many species of primates are reported to survive, at least over periods of several years, in impacted landscapes by modifying aspects of their activity budget, group size and composition, ranging patterns, and diet (Onderdonk & Chapman, 2000; Wong & Sicotte, 2007; Boyle & Smith, 2010).

The endangered Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti), a large-bodied species of nonhuman primate, that lives in social groups of several 100 individuals (Kirkpatrick et al., 1998). A survey in the early 1990s indicated that this species was confined to a narrow region between the Yangtze and Mekong rivers (98°37′–99°41′E, 26°14′–29°20′N). Their population size was estimated to be less than 2,000 individuals, distributed across 19 distinct social groups (Long et al., 1994). A study by Zhao et al. (2018) integrating data on evolutionary genetics and biogeographical information concluded that both the historical distribution (the past 2,000 years) and current population structure of the R. bieti appears to have been directly impacted by human activities, principally agricultural expansion resulting in severe habitat fragmentation of the Tibetan Plateau and by hunting (Liu et al., 2009).

Recent studies modeling habitat change and agricultural expansion across R. bieti’s range, predict an increase in forest fragmentation and a decrease in habitat quality resulting in range contraction over the next 25–75 years (Xiao et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2018). However, some of these studies were based on data collected in the early 1990s and therefore may not accurately represent the current demographic and ecological challenges and conservation pressures faced by R. bieti. The main purpose of our study is to: (1) investigate the current population size and distribution of the R. bieti, (2) conduct a landscape and spatial analysis of their distribution area, and (3) examine how present day habitat fragmentation influences R. bieti population size, genetic diversity, and changes in geographical distribution.

Methods

Study area and data collection

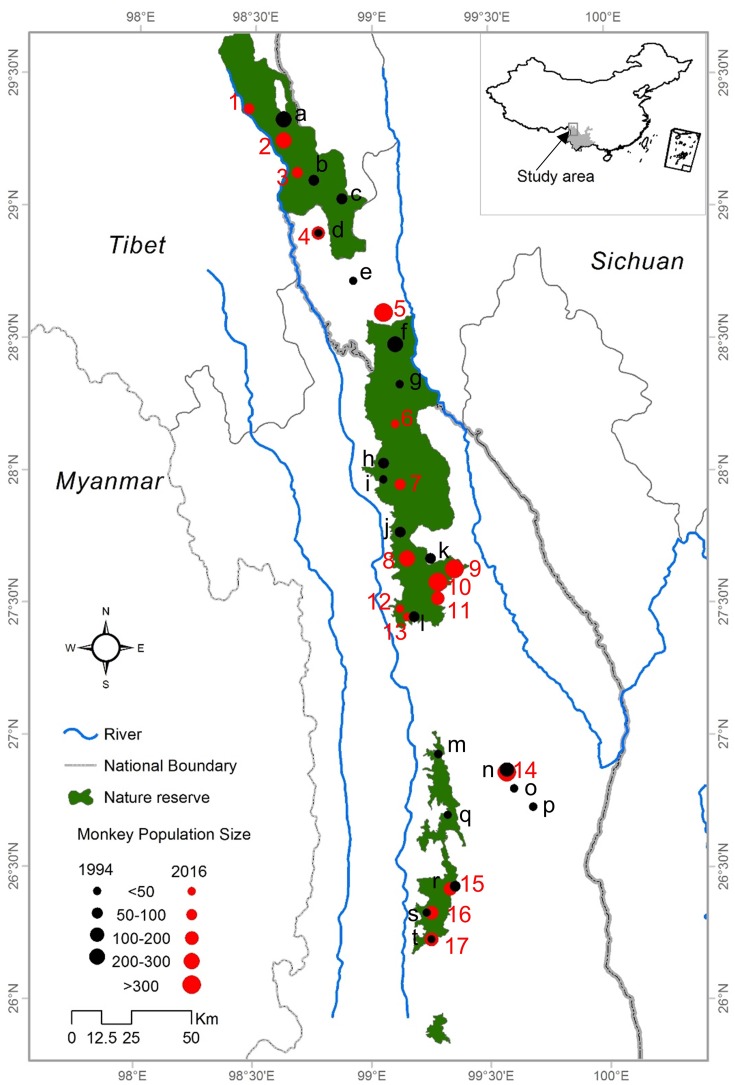

This field study was approved by State Forestry Administration of China. The study area is a narrow region of 17,000 km2 in the northwest of Yunnan Province and the Tibet Autonomous Region. It is bounded by the Mekong River to the west and the Yangtze River to the east (Long et al., 1994). The elevation of the study area varies from 1,300 to 5,400 m. Our study was conducted across all current distributional areas of R. bieti in Yunnan Province and Tibet. Each of the remaining wild groups was surveyed from January to November 2013 and April to September 2016. In order to obtain the most accurate information for this species, we conducted detailed surveys within its main distribution in three national nature reserves (Bamaxueshan, Honglaxueshan and Tianchi), one provincial nature reserve (Yunling), and two sites that are outside of protected reserves (Jinsichang and Bamei) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The study area and locations of the bands of R. bieti from 1994 to 2016.

Based on information of group location, a survey was conducted and the number of monkeys per group was censused. Specific locations of R. bieti groups were obtained from local forest rangers and officials who regularly patrol the reserves. R. bieti were counted directly using auxiliary telescopes to assist in observations (Wu, Zhong & Wu, 1988). Each monkey group was observed for 14–21 days, counting all individuals in the group (Wu, Zhong & Wu, 1988). The counting of monkeys in each group was based on the following method. Travel in R. bieti occurs both on the ground and in trees. However, when crossing open areas, the monkeys often walk slowly in a single or nearly single. A total of 17 groups were censused. R. bieti live in groups called multilevel societies (MLS), which are composed of several harem social and reproductive units (Qi et al., 2014). Each harem contains a single adult male, several adult females, and offspring. These harems travel, feed, and range together throughout the day and form a large band. Bands are followed by one or more all male units (AMU) that contain juvenile, sub-adult, and adult bachelor males. Because each band or MLS has been tracked by patrol officers for several years, we were able to obtain an accurate count of its size. This was accomplished by first counting the number of harems in each band and then estimating the number of monkeys per harem and per AMU to obtain a final total. In order to increase census accuracy, at least three researchers participated in each survey and counted/estimated the number of harems and harem sizes.

To monitor changes over time in R. bieti demography and distribution, we obtained information on R. bieti population size and location in 1990 from Long et al. (1994) and compared it with our current data. To assess relationships among suitable habit, population size, and gene flow, we conducted an analysis of genetic diversity among groups. The genetic diversity for each group was calculated using FSTAT 3.2 (Goudet, 1995) based on microsatellite dates from the analyses of 157 individuals’ samples (blood, muscle and faecal) in 2007 (Liu et al., 2007, 2009). Genetic information was obtained from 11 of the 17 known groups of R. bieti.

Landscape data and spatial analysis

We used a land cover map (30″ × 30″ resolution) derived from an assemblage of 13 SPOT5 images across the known distribution of R. bieti for 1990 and 2016. This covered an area of 17,000 km2 including the entire R. bieti range. Vegetation types suitable for R. bieti were defined as dark-coniferous forest dominated by species such as Abies georgei and mixed coniferous and broadleaf forest (Kirkpatrick et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 2003; Li et al., 2015). We then verified our habitat classification accuracy using data from the Conservation Information Centre of The Nature Conservancy of China. Fragmentation metrics for R. bieti were calculated using FRAGSTATS 4 (McGarigal & Marks, 1994). Patch density (PD, the number of patches divided by total landscape area) was used as indices of fragmentation, with low PD indicating a more connected landscape and high PD indicating a more fragmented landscape (Olsoy et al., 2016). A fragment was considered vegetatively suitable to sustain a population of R. bieti if it included dark-coniferous forest and mixed coniferous and broadleaf forest. Given the potential effect that habitat fragmentation can have on whether an area is suitable for R. bieti. Supplementary information of forested land, cropland, pasture land, and land reclamation (defined as primary forest converted into a secondary forest, pasture and cropland), as well as information on human population density, was extracted from the History Database of the Global Environment (the pixel of size of these data were 0.25 × 0.25 resolution; HYDE3.1: Goldewijk et al., 2011; He, Li & Zhang, 2015; Li, He & Zhang, 2016). We extracted values of human population density, cropland, and pasture (HYDE3.2; Goldewijk, 2016), all indicators of habitat fragmentation, between the years 1990 and 2016 with the function “extract” in R (R Core Team, 2017). We used Spearman correlations to check for simple linear relationships between the growth rate of the R. biet population and all environmental and landscape variables (fragmentation index, population density, area of cropland, area of pasture, density of households, and density of roads). Then, we applied multiple linear regression analyses to determine the partial and interactive effects of factors affecting R. bieti population size. Finally, we applied GLMs to determine the factors affecting R. bieti population size.

Results

Based on a census of 17 R. bieti subpopulation size isolated from each other and troop size ranged from 40 to 450 individuals. The mean number of harems per band was 12 ± 3.5. Across all subpopulations, the total number of R. bieti in 2016 was estimated at approximately 3,000 individuals. We found that population growth had varied significantly by region. Current population estimates in the central and southwestern zones of the species’ range (Fig. 1) (Baimaxueshan Nature Reserve and Yunling Nature Reserve) were 147% higher compared to values reported in 1994 (including the formation of three new groups: Gehuaqing, Baijixun (Yongan), Shikuadi). In contrast, size estimates for the southeastern and northern (Honglaxueshan Nature Reserve) areas increased by only 24% and 21%, respectively, from earlier estimates. This increase in population size was the result of an increase in the size of bands rather than the number of R. bieti bands. We found that six groups with populations sizes of less than 100 individuals in 1994 disappeared by 2016. These included those in Bajia, Adong, Houziqin, Heishan, Dapingzi, and Moziping. The population sizes of three groups (Cikatong, Milaka, and Akou (Anyi)) were found to decrease by 20–50% between 1994 and 2016 (Table 1). Four new groups were identified in our census, Zhina, Gehuaqing, Baijixun (Yongan), and Shikuadi. These bands inhabit the northern and southern regions of the species distribution and ranged in size of from 40 to 450 individuals (Table 1).

Table 1. Changes in the location of natural bands of R. bieti between 1994 to 2016.

| Site | Latitude | Longitude | 1994 | 2016 | Change group | Intraspecific genetic diversity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbiased Hz | Obs Hz | ||||||

| Zhina | 29.37 | 98.47 | – | 80 | new | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| Xiaochangdu | 29.33 | 98.62 | >200 | 280 | unchanged | – | – |

| Milaka | 29.13 | 98.75 | <100 | 60 | unchanged | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| Bajia | 29.03 | 98.87 | <100 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Bamei | 28.9 | 98.77 | <50 | 100 | unchanged | 0.59 | 0.54 |

| Adong | 28.72 | 98.92 | <50 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Wuyapuya | 28.48 | 99.1 | >200 | 400 | unchanged | 0.63 | 0.64 |

| Cikatong | 28.03 | 99.05 | 50–100 | 50 | unchanged | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| Guyoulong(guilong) | 27.97 | 99.05 | <50 | 80 | unchanged | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| Shiba | 27.77 | 99.12 | 50–100 | 200 | Unchanged | – | – |

| Guomorong(Xiangguqibg) | 27.67 | 99.25 | 50–100 | 480 | unchanged | 0.65 | 0.63 |

| Akou(Anyi) | 27.45 | 99.18 | 50–100 | 40 | unchanged | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| Jinsichang | 26.87 | 99.57 | 100–150 | 310 | unchanged | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| Neidaqin(Fuhe) | 26.43 | 99.35 | 50–100 | 120 | unchanged | 0.66 | 0.71 |

| Lashashan | 26.33 | 99.23 | <50 | 130 | unchanged | – | – |

| Houziqin | 26.93 | 99.28 | <50 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Longma | 26.23 | 99.25 | <50 | 140 | unchanged | 0.64 | 0.72 |

| Heishan | 26.7 | 99.32 | <50 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Dapingzi | 26.73 | 99.68 | <50 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Moziping | 26.8 | 99.6 | <50 | – | disappeared | – | – |

| Gehuaqing | 27.58 | 99.28 | – | 450 | new | – | – |

| Shikuadi | 27.52 | 99.28 | – | 120 | new | ||

| Pantiange | 27.47 | 99.15 | – | – | unchanged | – | – |

| Baijixun(Yongan) | 27.48 | 99.12 | – | 40 | new | – | – |

Our analysis of habitat fragmentation indicates that the southern populations of R. bieti (Tianchi nature reserve, Yunling nature reserve and Jinsichang, fragmentation index: 0.99), live in more fragmented habitats and are characterized by smaller band size compared to the Central (N = 9) and northern (N = 3) populations (Baimaxueshan nature reserve and Honglaxueshan nature reserve, fragmentation index: 0.59). In general, the GLMs indicated that the fragmentation index, human population size, and the area within a group’s range devoted to pasture was negatively correlated with R. bieti population size. In this case, after model selection based on AIC, only a few variables remained (population size = 0.85–3.09 fragmentation index −2.39 population density −0.49 pasture, R2 = 0.52, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The results of our census indicate that the construction of protected nature reserves (87% of the R. bieti live in protected areas) has effectively limited human disturbance and reduced hunting, leading to a population increase from less than 2,000 to almost 3,000 individuals over the past 25 years. During the 1980s, populations of R. bieti faced a set of severe anthropogenic challenges. For example, approximately 200,000 m3 of commercial logs were removed annually from their range, an entire band was killed by poachers (Long et al., 1994; Ding, Yang & Liu, 2003), and the area of suitable habitat decreased by 31% from 1958 to 1997 as large tracts of forests were converted into pastures for cattle grazing (Xiao et al., 2003). In addition, in Deqin country alone, approximately 430 R. bieti were killed for meat, fur, and medicine from 1970 to 1979, and 68 pieces of R. bieti fur or bone were sold in local stores (Bai, 1987). With the establishment of the Baimaxueshan Nature Reserve, the Honglashan Nature Reserve, the Yunling Nature Reserve and the Tianchi Nature Reserve between 1983 and 2003, R. bieti is now protected and this has effectively prevented poaching, the collection of forest products, and livestock grazing within their range. Simultaneously the Chinese government has banned all guns beginning in 1990s, and this has dramatically reduced poaching. Each of these measures has served to protect R. bieti and to promote their population recovery over the past 25 years.

Despite population increases, the conservation status of R. bieti continues to be negatively affected by forest fragmentation and the presence of human settlements in and around their range. Our results indicate that R. bieti population growth rates varied across its distribution with both increased habitat fragmentation and increased human population density negatively affecting R. bieti population growth rates. This was most evident in the southern region (Yunling and Tianchi Nature Reserves), where suitable habitats are highly fragmented and R. bieti population growth rates are low. The situation faced by R. bieti of fragmentation-induced reduction in habitat quality and resource availability also has adversely affected the long-term viability of other primate species (Wahungu et al., 2005; Arroyo-Rodríguez & Fahrig, 2014) and this has contributed to a primate extinction crisis worldwide (Estrada et al., 2017, 2018; Li et al., 2018).

In the case of R. bieti, forest fragmentation spatially isolates subpopulations and impeding gene flow. Moreover, the conversion of natural habitat to agricultural fields and pasture land leads to the local extinction of small populations, as in the case of the Adong, Houziqin, Heishan, Dapingzi, and Moziping R. bieti bands. Fragmentation also leads to reduction in the availability of large food patches, changes in tree species composition and diversity, and introduces edge effects leading to changes in soil moisture and local climate, resulting in a reduction in overall habitat quality (Laurance, Vasconcelos & Lovejoy, 2000). Lichen and fruit are important components of the diet of R. bieti, accounting for 50% of total feeding time (Grueter et al., 2009). Across most forested environments, ripe fruit is characterized by a patchy distribution in space and time. Spatial and temporal fruit patchiness is exacerbated in fragmented landscapes, limiting the ability of species (Estrada & Coates-Estrada, 1996). For example, mantled howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata) living in more fragmented landscapes spent more time traveling and searching for food than did groups living in less fragmented landscapes (Estrada & Coates-Estrada, 1996). We assume that given the large size of R. bieti bands, increased fragmentation results in increased challenges in locating sufficient food. Similarly, lichen is known to be negatively impacted by human-induced environmental change such as air pollution, and a decline in the production of lichen is likely to have a severely negative effect on R. bieti nutrient intake, reproduction, population growth rates, and survivorship (Grueter et al., 2008).

Our results also indicated that the population growth rate of R. bieti was negativity correlated with human population density and human accessibility to wildlife habitats. Based on our field observations, we noted that during the R. bieti breeding season (month 2 to month 6), local people go into the forest to pick cordyceps, which frightened and affects R. bieti breeding behavior by making R. bieti spending more time traveling. In addition, human accessibility to wildlife habitats has the potential to become a vector for the transmission of zoonotic diseases between humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife, and rapidly extirpate entire primate subpopulations from local areas (Patz et al., 2008; Lambin et al., 2010; Murray & Daszak, 2013; Gottdenker et al., 2014; Estrada et al., 2018). We found that in areas with human population densities of greater than 46 human/km2, R. bieti growth rates either increased very slowly (rate of 11.4%) or some small bands exhibited negative growth and disappeared from areas such as Bajia, Adong, Houziqin, Heishan, Dapingzi, and Moziping. This reduction has been offset, in part, by the addition of four newly formed bands (Zhina, Gehuaqing, Baijixun (Yongan), Shikuadi) and other bands increasing in size. Moreover, pastures serve as a barrier to migration for R. bieti (Kirkpatrick et al., 1998; Grueter et al., 2010) and therefore severely limit the movement of individuals across these highly transformed landscapes and the opportunity to expand into unoccupied habitats and form of new bands.

Our results revealed that R. bieti populations in the Yunling Nature Reserve and in Jinshichang are the most isolated, and characterized by certain unique haplotypes (haplotype M1-M4, M6-M11, and M29-M30) (Liu et al., 2007). Moreover, despite the fact that total population size has increased dramatically over the past 25 years, the population size of three bands (Milaka, Cikatong, and Akou (Anyi)) has markedly decreased, exacerbating the loss of genetic diversity (Table 1). We suggest that management decisions for endangered species should not focus solely on population size but also consider subpopulation genetic diversity. We recommend that effective conservation policies for this species should prioritize protecting certain targeted populations such as Milaka, Cikatong, and Akou (Anyi) that have high intraspecific genetic diversity but low growth rates (Table 1). In addition, government policies that promote the alleviation of human poverty, especially in rural communities, represent an important conservation tool that indirectly protects R. bieti. In this regard, the Chinese government has encouraged local farmers to return land to natural forest, prohibited logging, and relocate from Nature Reserves. This serves to reduce human interference and protect habitats that are critical to the survival of R. bieti as well as others threatened taxa.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Administration Bureaus of Baimaxueshan National Nature Reserve and Honglaxueshan National Nature Reserve for their support in field work. We also thank Chrissie, Sara, Jenni, and Yu Zhang for their support.

Funding Statement

This project was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA19050202), the National Key R & D Program of China (2016YFC0503200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31821001) and the State Forestry Administration of China. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Xumao Zhao conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Baoping Ren performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Dayong Li performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Zuofu Xiang performed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools.

Paul A. Garber authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Ming Li conceived and designed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Field Study Permissions

The following information was supplied relating to field study approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

This field experiments were approved by State Forestry Administration of China (the Second National Survey on Terrestrial Wildlife Resources in China).

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available in Table 1.

References

- Arroyo-Rodríguez & Fahrig (2014).Arroyo-Rodríguez V, Fahrig L. Why is a landscape perspective important in studies of primates? American Journal of Primatology. 2014;76(10):901–909. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai (1987).Bai S. The investigation of poaching Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. Wild Animals. 1987;1:004. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol & Peres (2013).Benchimol M, Peres CA. Anthropogenic modulators of speciesarea relationships in Neotropical primates: a continental-scale analysis of fragmented forest landscapes. Diversity and Distribution. 2013;19(11):1339–1352. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle & Smith (2010).Boyle SA, Smith AT. Behavioral modifications in northern bearded saki monkeys (Chiropotes satanaschiropotes) in forest fragments of central Amazonia. Primates. 2010;51(1):43–51. doi: 10.1007/s10329-009-0169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, Ehrlich & Dirzo (2017).Ceballos G, Ehrlich PR, Dirzo R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114(30):E6089–E6096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704949114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks & Sanjayan (2006).Crooks KR, Sanjayan MA. Connectivity conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Didham, Kapos & Ewers (2012).Didham RK, Kapos V, Ewers RM. Rethinking the conceptual foundations of habitat fragmentation research. Oikos. 2012;121(2):161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.20273.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Yang & Liu (2003).Ding W, Yang S, Liu Z. The influence of the fragmentation of habitats at upon the number of population of Rhinopithecus bieti. Acta Anthropologica Sinica. 2003;22:338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas et al. (2014).Dornelas M, Gotelli NJ, McGill B, Shimadzu H, Moyes F, Sievers C, Magurran AE. Assemblage time series reveal biodiversity change but not systematic loss. Science. 2014;344(6181):296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.1248484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada & Coates-Estrada (1996).Estrada A, Coates-Estrada R. Tropical rain forest fragmentation and wild populations of primates at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. International Journal of Primatology. 1996;17(5):759–783. doi: 10.1007/bf02735263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada et al. (2017).Estrada A, Garber PA, Garber PA, Rylands AB, Roos C, Fernandez-Duque E, Fiore AD, Nekaris AI, Nijman V, Heymann EW, Lambert JE, Rovero F, Barelli C, Setchell JM, Gillespie TR, Mittermeier RA, Arregoitia LV, De Guinea M, Gouveia S, Dobrovolski R, Shanee S, Shanee N, Boyle SA, Fuentes A, MacKinnon KC, Amato KR, Meyer ALS, Wicj S, Sussman RW, Pan RL, Kone I, Li BG. Impending extinction crisis of the world’s primates: why primates matter. Science Advance. 2017;3(1):e1600946. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada et al. (2018).Estrada A, Garber PA, Mittermeier RA, Wich W, Goveia S, Dobrovolski R, Nekaris KAI, Nijman V, Rylands AB, Maisels F, Williamson EA, Bicca-Marques J, Fuentes A, Jerusalinsky L, Johnson S, Rodrigues De Melo F, Oliveira L, Schwitzer C, Roos C, Cheyne SM, Martins Kierulff MC, Raharivololona B, Talebi M, Ratsimbazafy J, Supriatna J, Boonratana R, Wedana M, Setiawan A. Primates in peril: the significance of Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for global primate conservation. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4869. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewers & Didham (2007).Ewers RM, Didham RK. The effect of fragment shape and species’ sensitivity to habitat edges on animal population size. Conservation Biology. 2007;21(4):926–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottdenker et al. (2014).Gottdenker NL, Streicker DG, Faust CL, Carroll CR. Anthropogenic land use change and infectious diseases: a review of the evidence. EcoHealth. 2014;11(4):619–632. doi: 10.1007/s10393-014-0941-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldewijk (2016).Goldewijk KK. A historical land use data set for the holocene; HYDE 3.2 (replaced). Dataset. DANS. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Goldewijk et al. (2011).Goldewijk KK, Beusen A, Van Drecht G, De Vos M. The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human-induced global land-use change over the past 12,000 years. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2011;20(1):73–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00587.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet (1995).Goudet J. FSTAT (Version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. Journal of Heredity. 1995;86(6):485–486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter et al. (2010).Grueter CC, Li DY, Feng SK, Ren BP. Niche partitioning between sympatric rhesus macaques and Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys at Baimaxueshan Nature Reserve, China. Zoological Research. 2010;31(5):516–522. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2010.05516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter et al. (2009).Grueter CC, Li D, Ren B, Wei F, Xiang Z, Van Schaik CP. Fallback foods of temperate-living primates: a case study on snub-nosed monkeys. American Journal of Primatology. 2009;140(4):700–715. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter et al. (2008).Grueter CC, Li DY, Van Schaik CP, Ren BP, Long YC, Wei FW. Ranging of snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) at the Samage Forest, Yunnan. I. Characteristics of range use. International Journal of Primatology. 2008;29:1121–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad et al. (2015).Haddad NM, Brudvig LA, Clobert J, Davies KF, Gonzalez A, Holt RD, Lovejoy TE, Sexton JO, Austin MP, Collins CD, Cook WM, Damschen EI, Ewers RM, Foster BL, Jenkins CN, King AJ, Laurance WF, Levey DJ, Margules CR, Melbourne BA, Nicholls AO, Orrock JL, Song DX, Townshend JR. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science Advance. 2015;1(2):e1500052. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Li & Zhang (2015).He F, Li S, Zhang X. A spatially explicit reconstruction of forest cover in China over 1700–2000. Global and Planetary Change. 2015;131:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick et al. (1998).Kirkpatrick RC, Long YC, Zhong T, Xiao L. Social organization and range use in the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus bieti. International Journal of Primatology. 1998;19:13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin et al. (2010).Lambin EF, Tran A, Vanwambeke SO, Linard C, Soti V. Pathogenic landscapes: interactions between land, people, disease vectors, and their animal hosts. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2010;9(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1476-072x-9-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurance, Vasconcelos & Lovejoy (2000).Laurance WF, Vasconcelos HL, Lovejoy TE. Forest loss and fragmentation in the Amazon: implications for wildlife conservation. Oryx. 2000;34(1):39–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3008.2000.00094.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, He & Zhang (2016).Li S, He F, Zhang X. A spatially explicit reconstruction of cropland cover in China from 1661 to 1996. Regional Environmental Change. 2016;16(2):417–428. doi: 10.1007/s10113-014-0751-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2018).Li BG, Li M, Li JH, Fan PF, Ni QY, Lu JQ, Zhou XM, Long YC, Jiang ZG, Zhang P, Huang ZP, Huang CM, Jiang XL, Pan RL, Gouveia S, Dobrovolski R, Grueter CC, Oxnard C, Groves C, Estrada A, Garber PA. The primate extinction crisis in China: immediate challenges and a way forward. Biodiversity Conservation. 2018;27:3301–3327. [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2015).Li L, Xue Y, Wu G, Li D, Giraudoux P. Potential habitat corridors and restoration areas for the black-and-white snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus bieti in Yunnan, China. Oryx. 2015;49(4):719–726. doi: 10.1017/s0030605313001397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2007).Liu Z, Ren B, Wei F, Long Y, Hao Y, Li M. Phylogeography and population structure of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) inferred from mitochondrial control region DNA sequence analysis. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16(16):3334–3349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2009).Liu ZJ, Ren BP, Wu R, Zhao L, Hao Y, Wang BS, Wei FW, Long Y, Li M. The effect of landscape features on population genetic structure in Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) implies an anthropogenic genetic discontinuity. Molecular Ecology. 2009;18(18):3831–3846. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2009.04330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long et al. (1994).Long YC, Kirkpatrick CR, Zhong T, Xiao L. Report on distribution, population and ecology of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) Primates. 1994;35(2):241–250. doi: 10.1007/bf02382060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mace et al. (2010).Mace GM, Collen B, Fuller RA, Boakes EH. Population and geographic range dynamics: implications for conservation planning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;365(1558):3743–3752. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magurran & Dornelas (2010).Magurran AE, Dornelas M. Biological diversity in a changing world. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;365(1558):3593–3597. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarigal & Marks (1994).McGarigal K, Marks BJ. General Technical Report. PNW-GTR-351. Portland: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station; 1994. Spatial pattern analysis program for quantifying landscape structure; pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- McGill (2015).McGill B. Biodiversity: land use matters. Nature. 2015;520(7545):38–39. doi: 10.1038/520038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2006).Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. 2006. www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf

- Murray & Daszak (2013).Murray KA, Daszak P. Human ecology in pathogenic landscapes: two hypotheses on how land use change drives viral emergence. Current Opinion in Virology. 2013;3(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold et al. (2015).Newbold T, Hudson LN, Hill SL, Contu S, Lysenko I, Senior RA, Börger L, Bennett DJ, Choimes A, Collen B, Day J, De Palma A, Díaz S, Echeverria-Londoño S, Edgar MJ, Feldman A, Garon M, Harrison ML, Alhusseini T, Ingram DJ, Itescu Y, Kattge J, Kemp V, Kirkpatrick L, Kleyer M, Correia DL, Martin CD, Meiri S, Novosolov M, Pan Y, Phillips HR, Purves DW, Robinson A, Simpson J, Tuck SL, Weiher E, White HJ, Ewers RM, Mace GM, Scharlemann JP, Purvis A. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature. 2015;520(7545):45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onderdonk & Chapman (2000).Onderdonk DA, Chapman CA. Coping with forest fragmentation: the primates of Kibale National Park, Uganda. Current Opinion in Virology. 2000;21(4):587–611. [Google Scholar]

- Olsoy et al. (2016).Olsoy PJ, Zeller KA, Hicke JA, Quigley HB, Rabinowitz AR, Thornton DH. Quantifying the effects of deforestation and fragmentation on a range-wide conservation plan for jaguars. Biological Conservation. 2016;203:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Patz et al. (2008).Patz JA, Olson SH, Uejio CK, Gibbs HK. Disease emergence from global climate and land use change. Medical Clinics of North America. 2008;92(6):1473–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimm et al. (1995).Pimm SL, Russell GJ, Gittleman JL, Brooks TM. The future of biodiversity. Science. 1995;269(5222):347–350. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5222.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi et al. (2014).Qi XG, Garber PA, Ji W, Huang ZP, Huang K, Zhang P, Guo ST, Wang XW, He G, Zhang P, Li BG. Satellite telemetry and social modeling offer new insights into the origin of primate multilevel societies. Nature Communication. 2014;5(1):5296. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2017).R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raup (1995).Raup DM. Extinction rates. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wahungu et al. (2005).Wahungu GM, Muoria PK, Moinde NN, Oguge NO, Kirathe JN. Changes in forest fragment sizes and primate population trends along the River Tana floodplain, Kenya. African Journal of Ecology. 2005;43(2):81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.2005.00535.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson et al. (2016).Wilson MC, Chen XY, Corlett RT, Didham RK, Ding P, Holt RD, Holyoak M, Hu G, Hughes AC, Jiang L, Laurance WF, Liu J, Pimm SL, Robinson SK, Russo SE, Si X, Wilcove DS, Wu J, Yu M. Habitat fragmentation and biodiversity conservation: key findings and future challenges. Landscape Ecology. 2016;31(2):219–227. doi: 10.1007/s10980-015-0312-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong et al. (2013).Wong MHG, Li R, Xu M, Long YC. An integrative approach to assessing the potential impacts of climate change on the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. Biology Conservation. 2013;158:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong & Sicotte (2007).Wong SNP, Sicotte P. Activity budget and ranging patterns of Colobus vellerosus in forest fragments in central Ghana. Folia Primatologica. 2007;78(4):245–254. doi: 10.1159/000102320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zhong & Wu (1988).Wu BQ, Zhong T, Wu J. A preliminary survey of ecology and behavior on a Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) group. Zoological Research. 1988;9:373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao et al. (2003).Xiao W, Ding W, Cui LW, Zhou RL, Zhao QK. Habitatsat degradation of Rhinopithecus bieti in Yunnan, China. International Journal of Primatology. 2003;24:389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao et al. (2018).Zhao X, Ren B, Garber PA, Li X, Li M. Impacts of human activity and climate change on the distribution of snub-nosed monkeys in China during the past 2000 years. Diversity and Distribution. 2018;24(1):92–102. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available in Table 1.