Abstract

Efficient regulation of a complex genetic response requires that the gene products, which catalyze the response, be synthesized in a temporally ordered manner to match the sequential nature of the reaction pathway they act upon. Transcription regulation networks coordinate this aspect of cellular control by modulating transcription factor (TF) concentrations through time. The effect a TF has on the timing of gene expression is often modeled assuming that the TF-promoter binding reaction is in thermodynamic equilibrium with changes in TF concentration over time, however, non-equilibrium dynamics resulting from relatively slow TF binding kinetics can result in different network behavior. Here, I highlight a recent study of the bacterial SOS response, where a single TF regulates multiple target promoters, to show how a disequilibrium of TF binding at promoters results in a more complex behavior, enabling a larger temporal separation of promoter activities that depends not only upon slow TF binding kinetics at promoters, but also on the magnitude of the response stimulus. I also discuss the dependence of network behavior on specific TF regulatory mechanisms and the implications non-equilibrium dynamics have for stochastic gene expression.

Keywords: SOS response, transcription factor, kinetics, promoter, DNA damage, LexA

To survive, cells must adapt to fluctuations in the environment by sensing and responding to these changes rapidly. Cellular responses often involve the coordinated expression of a group of genes that carry out a specific biological function by catalyzing all of the required biochemical transformations in a reaction pathway. Efficient control of the cellular response not only requires that its gene regulatory factors have a specific network structure (Glazier and Krysan. 2018), but also that the time-interval over which each gene is expressed be matched to the temporal-sequential nature of the reaction pathways that they act upon. In this way, the cell avoids inhibiting the pathway, inciting toxicity, or wasting energy by expressing a gene before it can be actualized.

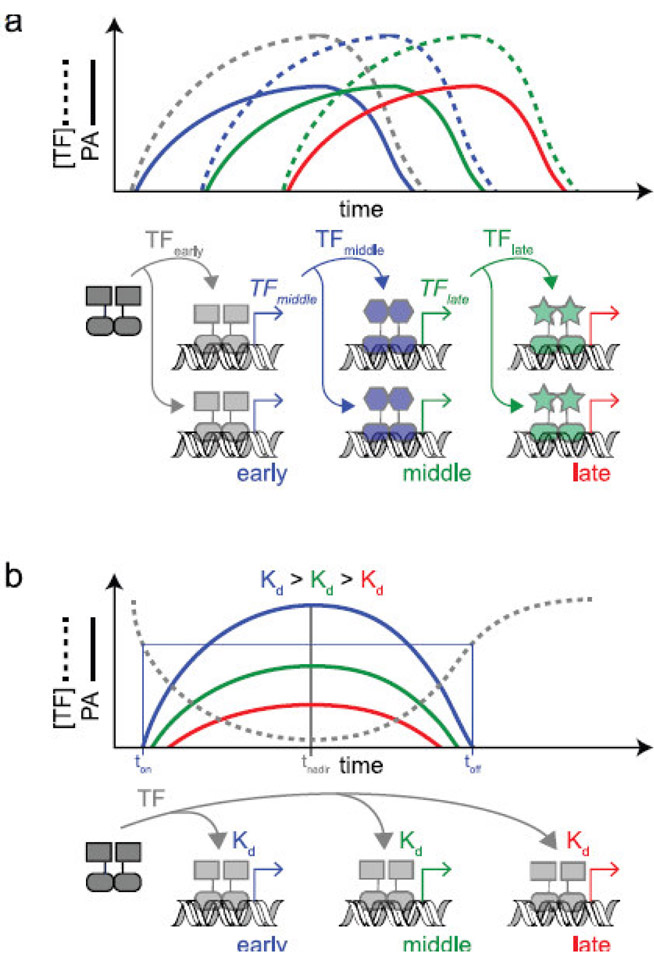

Transcription regulation networks play an important role in coordinating the relative timing of gene expression and thus are critical to this aspect of cellular control (Shen-Orr et al. 2002). The underlying logic of the temporal sequence has been elucidated for several gene networks. For example, bacteriophage λ utilizes a cascade of transcription factors (TFs) to separate its gene expression into ‘very early’, ‘early’, and ‘late’ gene programs. The ‘very early’ genes include TFs that activate the ‘early’ genes, which, in turn, include TFs that activate the ‘late’ genes. This serial cascade enforces the temporality of gene expression because, for each TF in the cascade, the transcription, translation, and protein folding steps take time to complete before the TF becomes active (Fig. 1a). For phage λ, this timing not only enables strict regulation of the ‘genetic switch’ between its lytic and lysogenic lifestyles, but also efficient transit through the required biochemical transformations along each pathway (Ptashne. 2004). The flagellar biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli offers another example of a TF cascade. In this system, the first genes to be expressed encode the TF acting as the master regulator of the pathway, then this ‘first’ TF activates the expression of a second set of genes encoding the basal body and hook proteins that anchor the flagellar apparatus to the cell membrane. The ‘first’ TF also activates expression of a ‘second’ TF gene, which, in turn, leads to the expression of the final set of genes that compose the flagellum and chemotaxis navigation system. Thus, the flagellar apparatus appears to be assembled in a logical order, starting with a scaffold that anchors the apparatus to the cell membrane, then followed by sequential addition of the remaining components necessary for torque generation (Kalir et al. 2001).

Fig. 1.

Timing of promoter activity in simple transcription regulation networks. a. Transcription factor (TF) cascade. Multiple TFs act in series to temporally order the transcription of early, middle, and late genes. In this example, each TF is an activator. The graph shows the relative concentrations of the different TFs (dotted lines) and the relative activities of the promoters they act upon (solid lines). Line colors indicate the different TFs and promoters shown in the schematic. Timing differences between promoters emerge here largely due to the time delay imposed by each TF’s own transcription, translation, folding, maturation, and degradation rates. b. Single-input module (SIM). One TF acts on multiple target promoters to temporally order the transcription of early, middle, and late genes. In this example, the TF is a repressor and each promoter has a similar maximal activity, but with a different equilibrium binding affinity (Kd) for the TF. Here, the TF-promoter interaction is in thermodynamic equilibrium with the changing TF concentration through time. The time of each promoter’s activation (ton) and shut-off (toff) are determined by its Kd and occur when the TF concentration crosses an arbitrarily defined activity cut-off (shown here as the x-axis). Under these conditions, promoters with smaller Kd values are the last to turn-on and the first to shut-off and all promoters display peak activity at the time of the TF nadir (tnadir). Large timing differences between promoter activities rely on large Kd differences and slow changes in TF concentration over time

Underlying temporal logic has also been described in transcription regulation networks termed single-input modules (SIMs), where, instead of a cascade of multiple TFs, just one TF regulates the expression of multiple target promoters (Fig. 1b). For example, in E. coli, the set of genes encoding the enzymes that convert glutamate to ornithine along the arginine biosynthetic pathway are composed of several different operons, all of which are, repressed by ArgR. These operons are transcribed in a temporal order that matches the same sequence in which they are needed in the biosynthetic reaction pathway. Modeling the sequential timing of gene expression onto the reaction pathway supports the idea that this timing strategy, termed ‘just-in-time transcription’, is energy efficient, since the organism then does not waste energy synthesizing gene products before they can be actualized in the pathway (Zaslaver et al. 2004). Another remarkable example of temporal ordering of gene expression in a SIM is the bacterial DNA damage repair pathway, also known as the SOS response, which is regulated by the LexA repressor. Here, however, the temporal separation of gene expression into ‘early’, ‘middle’, and ‘late’ genes that follows a genotoxic insult to the cell facilitates a transition from high-fidelity DNA repair activities early in the response to mutagenic DNA damage tolerance activities late in the response. The SOS response begins to shut-off as soon as DNA repair is complete; thus, the expedient expression of the early DNA repair and recombination genes is believed to limit the toxicity of pro-mutagenic late genes only to situations where the high-fidelity repair process is overwhelmed by a large amount of DNA damage (Friedberg et al. 1995). It has been hypothesized that this additional regulation can tune the mutation rate of a bacterial population to the level of environmental stress, thereby balancing the risk of deleterious mutations against the chance a new beneficial mutation could arise to circumvent the imposed stress (Radman. 1999). Regardless, this type of stress-induced mutagenesis is clinically concerning, potentially linking antibiotic exposure directly to antibiotic resistance via a causal mechanism (Culyba et al. 2015, Cirz et al. 2005).

Models of temporal promoter activities within transcription regulation networks often assume TF binding to a promoter is in a rapid thermodynamic equilibrium with changing TF levels in the cell over time. However, this assumption is rarely validated and non-equilibrium dynamics, due to slow TF binding kinetics, can result in different promoter activation kinetics. In the context of a SIM, where each promoter in the network may have different TF binding kinetics, non-equilibrium dynamics could cause a more extreme temporal separation of the promoter activities and lead to a temporal ordering of the promoters. Although temporal ordering in SIMs has been observed previously (Ronen et al. 2002, Zaslaver et al. 2004), the underlying mechanism has been unclear since, even within the same network, promoter sequences are divergent; thus alternative promoter features could be responsible for timing differences, such as promoter strength, location of the TF binding site relative to the transcription start site, or the kinetics of the RNA polymerase-promoter interaction. Moreover, the specific chromosomal context of each promoter could play a role due to the regulation occurring on neighboring genes or differences in DNA superhelicity (Meyer et al. 2018). Recently, however, a systematic study of the bacterial SOS response found that non-equilibrium dynamics were responsible for the observed temporal ordering (Culyba et al. 2018).

In the SOS response, a single repressor protein, LexA, serves as the TF regulating approximately 40 target promoters and each promoter has different LexA binding kinetics. Furthermore, for most genes, LexA is the only known TF, so it is especially instructive to understand how non-equilibrium dynamics could affect this system. The kinetics of a given promoter’s transition to the de-repressed state, and its subsequent return to the repressed state, can be modeled by considering the reversible LexA-promoter dissociation reaction,

where ‘LexA:P’ and ‘P’ represent the promoter occupied and unoccupied states, respectively. Understanding how this reaction responds to LexA concentrations that change through time yields predictions for promoter activity as a function of time. Here, we assume that ‘promoter activity’, defined as the rate of mRNA copy production, is proportional to the probability of the unoccupied promoter state, ‘P’. If the forward and reverse reaction rates are equal, then the reaction is in equilibrium and the equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd, is given by,

where koff and kon refer to the rate-constants for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively. In the absence of DNA damage, LexA levels are maintained at a high steady-state concentration in the cell, the system achieves an equilibrium favoring the left side of the reaction, which is the promoter occupied state, and transcription is repressed. After DNA damage, however, LexA is degraded over a time-scale of minutes, reaches a concentration nadir in the cell, and then re-accumulates after the DNA damage has been repaired.

If one assumes the forward and reverse reaction rates are relatively fast (large values for koff and kon), as compared to the rate of changing LexA concentrations in the cell, then thermodynamic equilibrium is maintained throughout the fall and rise in LexA concentration over time. In this ‘equilibrium’ model, promoter occupancy at any given time-point during this period is dictated by the total amount of intact LexA present in the cell and the Kd for that promoter. When considering the entire network of promoters, each with a different Kd value, then timing differences between genes for promotor activation and shut-off are expected to be relatively modest and follow an order based on their differing Kd values, with the promoter with the lowest Kd value being the last to turn-on and first to turn-off. In addition, under equilibrium conditions, the peak activity for all the promoters, regardless of specific Kd values, will occur at the same time, which is the time of the LexA concentration nadir (Fig. 1b).

To experimentally test this equilibrium model, a simplified SOS system was constructed in E. coli and promoter activity was measured through time. In these experiments, a series of recA promoters controlling gfp expression were derived. The promoters were identical, except for one or two point mutations in the LexA operator region that altered LexA binding kinetics. In contrast to the above predictions for timing, the data showed a more extreme temporal ordering of promoter activity (Culyba et al. 2018). Instead of occurring at the same time after SOS activation, the peak activity of each promoter occurred at a different time. Furthermore, the time interval between SOS activation and peak activity showed an inverse relationship to LexA-operator dissociation rates measured in vitro. This suggested that LexA dissociation from some promoters is slow enough to become rate limiting in vivo, thus placing the reaction out of equilibrium with falling and rising LexA levels in the cell. For these promoters, the LexA dissociation rate, and not just the total amount of LexA in the cells, is a significant determinant of the promoter state as a function of time. When considering the entire network of promoters under non-equilibrium conditions, the promoter with the smallest koff value is the last to turn-on and last to shut-off. These data showed that, for a large subset of SOS gene promoters, the LexA-promoter binding reaction does not maintain thermodynamic equilibrium with the fall and rise in LexA concentrations that occurs during the SOS response. Therefore, a kinetic model of temporal promoter activity, one that also considers the rates of TF dissociation and association with the promoter (koff and kon) and not just the LexA concentration and Kd, is required to accurately predict the timing of promoter activity in this system (Culyba et al. 2018). From this perspective, promoters with fast TF binding kinetics (relative to the rate of changing LexA concentrations) are under ‘thermodynamic’ control and those with slow TF binding kinetics are under ‘kinetic’ control. The observed temporal ordering of promoter activities thus relies on slow TF binding kinetics.

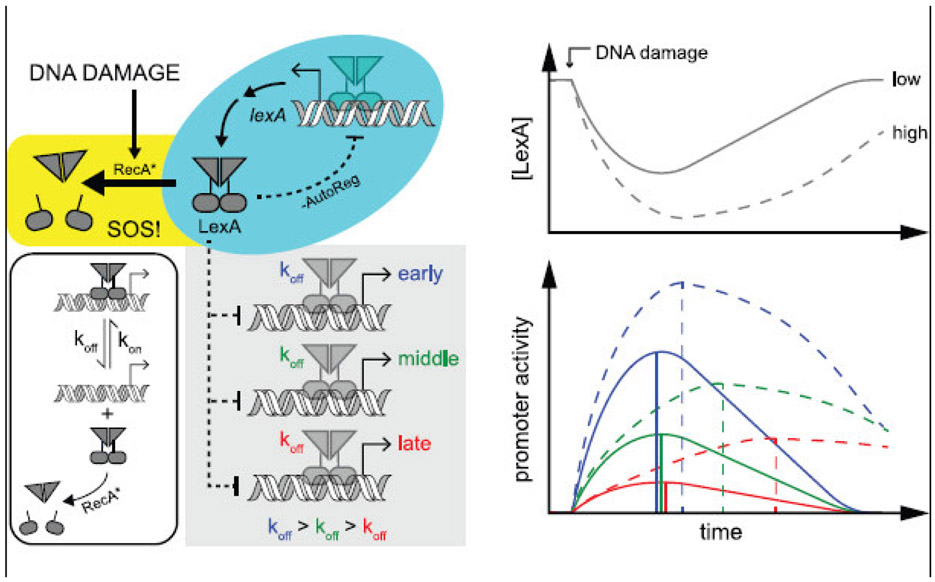

As mentioned above, the nature of the SOS response changes depending on the amount of DNA damage incurred by the cell and, interestingly, a DNA damage dose-dependency was also observed in the timing of promoter activity. With lower amounts of DNA damage, only a subset of SOS genes are fully transcriptionally active and all genes display peak promoter activity at the same time. Whereas with higher amounts of DNA damage, all SOS genes become fully activated, but the timing of peak promoter activities varies between genes and timing differences increase with greater amounts of DNA damage (Culyba et al. 2018). This dose-dependency of promoter activity timing arises because the kinetics of LexA depletion and re-accumulation are dose-dependent: greater amounts of DNA damage result in lower LexA concentrations that are sustained at low levels for a longer period of time (Sassanfar and Roberts. 1990). With lower doses of DNA damage, the relatively small drop in LexA concentration is followed by rapid reaccumulation of LexA and thus any minor disequilibrium that might occur is undetectable. Under these conditions, all SOS genes display their peak promoter activities at approximately the same time. In contrast, with higher amounts of DNA damage, the rapid and sustained depletion of LexA that occurs allows promoters with slow LexA dissociation kinetics (small values for koff) enough time to achieve the LexA unoccupied state. This results in a temporal ordering of SOS promoter activities that is not just dependent on the LexA binding kinetics of different promoters, but also on the dose of DNA damage imposed on the cell (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Behavior of the ‘non-equilibrium SIM’ of the SOS response. In the absence of DNA damage, steady-state LexA levels are maintained by the negative auto-regulatory circuit of the lexA gene (cyan box). After DNA damage, RecA* induces the rapid auto-proteolysis of the unbound form of LexA, marking the start of the SOS response (yellow box). The reversible LexA-promoter dissociation reaction (unshaded box) displays different binding kinetics for each SOS promoter (grey box). Top right: LexA levels fall, reach a nadir, and then re-accumulate. ‘High’ amounts of DNA damage (dotted line) result in LexA concentrations that are both lower and slower to recover than ‘low’ amounts of DNA damage (solid line). Bottom right: Traces indicate activities of promoters with different koff values (colors), but with the same kon values. Vertical lines indicate the time-point at which peak activity is achieved. Under ‘low’ DNA damage conditions (solid lines), re-accumulation of LexA is rapid, disequilibrium is minor, and promoter activities have similar timing. Under ‘high’ DNA damage conditions (dotted lines), a disequilibrium manifests causing promoters with slow LexA dissociation rates (lower values for koff) to display longer time intervals until reaching peak promoter activity. In contrast to equilibrium conditions (Fig. 1b), promoters with smaller koff values are the last to turn-on and shut-off and promoters do not display peak activity at the time of the TF nadir. Large timing differences between promoter activities rely on large koff differences and a relatively rapid rate of LexA depletion

It is of interest to understand how the specific biochemical mechanisms of a TF’s regulation affect activation and shut-off kinetics from a gene network point of view. For example, LexA autoproteolysis, and thus the SOS response, is triggered by the formation of activated RecA (termed RecA*) in the cell, however, LexA is resistant to RecA*-induced autoproteolysis when in its DNA-bound form (Butala et al. 2011), so only the unbound form is cleaved (Fig. 2, yellow box). Therefore, even after the SOS response has been triggered and RecA* has formed, intact LexA repressor must dissociate from the promoter before it can be inactivated by RecA* (Fig. 2, unshaded box). This mechanism allows LexA-promoter dissociation to be the rate-limiting step (instead of LexA autoproteolysis) to control the transition to the de-repressed promoter state and it may be essential for temporal ordering of promoter activity in the SOS system (Culyba et al. 2018). In contrast, the repressor of the lac operon, LacI, can be inactivated in its DNA-bound form by binding a small molecule inducer, increasing its dissociation kinetics with the promoter by more than a factor of ten. Thus, for lac, a simple mass-action equation, such as that in Fig. 2, describing the competition of the inducer and operator for the repressor is inadequate (Riggs et al. 1970) and additional linked equilibria, which account for faster dissociation of the operator-repressor-inducer complex, are required (Lewis. 2011).

How could non-equilibrium dynamics of TF binding at promoters be of benefit to the cell? I speculate that by utilizing a non-equilibrium mechanism for the SIM of the SOS response, the cell can achieve more significant temporal separations of gene activity, on the order of the cell doubling period, while still maintaining rapid response kinetics at the onset of DNA damage and completion of DNA repair. By comparison, under strict equilibrium conditions, the timing of peak activities would be the same for all promoters and the first promoters to turn on would be the last to turn off (Fig. 1b), thus the temporal activity curves of different promoters could not fully separate from one another with respect to timing. The specific arrangement of the SOS network as a ‘non-equilibrium SIM’ (Fig. 2) may, therefore, enable the cell to achieve a rapid response to DNA damage, a rapid shut-off after DNA repair is achieved, and also an efficient temporal separation of promoter activities. It seems likely that non-equilibrium dynamics play a role in the transcriptional timing of other gene networks with SIM architecture as well (Zaslaver et al. 2004), but this remains to be investigated.

Non-equilibrium dynamics might also cause interesting behaviors on the single-cell level due to statistical considerations. Consider the SOS response again, where only the free, unbound pool of repressor molecules can be inactivated. For a promoter that is under kinetic control, after rapid inactivation of repressor, the off-rate of the bound repressor from the promoter will be the rate-limiting step for transcription initiation. The promoter will eventually turn-on, but not until the promoter-bound repressor molecule dissociates, which will occur in a stochastic manner and, by this point in time, might be the last active repressor molecule remaining in the cell. When considering an entire population of cells, the time interval to the dissociation event will have a mean value of ~1/koff. Single cells in this population, however, will each have a different value for the dissociation time which, together, will describe the variance around this mean. Thus, under non-equilibrium conditions, it is expected that the same promoter in some cells will ‘fire early’ and, in other cells, ‘fire late’. The transcriptional ‘noise’ associated with this type of stochastic behavior would not be expected to occur to the same degree with a promoter that is under thermodynamic regulation, where, by definition, an ensemble of TF molecules is in a rapid equilibrium with the promoter. Here, instead of a single dissociation event, now many binding/dissociation events occur during the same time interval, effectively averaging out the variance. Stochastic, or ‘noisy’, gene expression is a significant source of non-genetic variation that enables clonal cell populations to survive changing environments (Munsky et al. 2012) and it is of interest to determine to what extent the kinetics and specific mechanism of TF binding, as well as other gene regulatory factors (Bidnenko and Bidnenko. 2018), contribute to this phenomenon.

In conclusion, transcription regulation networks are critical for rapid cellular responses to changing environments and the relative timing of promoter activation within a network is important for efficient regulation. Most models of these networks assume TF binding at promoters is in thermodynamic equilibrium with TF levels that change in time, however, this assumption likely obscures more complex kinetic behaviors. The kinetic behaviors that arise from non-equilibrium dynamics can affect the extent, timing, and possibly the ‘noise’ of gene expression and depend on the specific regulatory mechanisms of the TF. Thus, understanding the kinetic constraints of a diverse group of TFs is important, as it will provide insight into both the evolution of naturally occurring transcription regulation networks and inform the design of synthetic gene regulatory networks engineered for practical applications such as gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Rahul M. Kohli for his insightful comments and suggestions. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K08-AI127933).

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K08-AI127933).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Bidnenko E and Bidnenko V (2018) Transcription termination factor Rho and microbial phenotypic heterogeneity. Curr.Genet 64:541–546. doi: 10.1007/s00294-017-0775-7 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butala M, Klose D, Hodnik V, Rems A, Podlesek Z, Klare JP, Anderluh G, Busby SJ, Steinhoff HJ, Zgur-Bertok D (2011) Interconversion between bound and free conformations of LexA orchestrates the bacterial SOS response. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:6546–6557. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr265 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, de Crecy-Lagard V, Craig WA, Romesberg FE (2005) Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 3:el76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culyba MJ, Kubiak JM, Mo CY, Goulian M, Kohli RM (2018) Non-equilibrium repressor binding kinetics link DNA damage dose to transcriptional timing within the SOS gene network. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007405 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culyba MJ, Mo CY, Kohli RM (2015) Targets for Combating the Evolution of Acquired Antibiotic Resistance. Biochemistry 54:3573–3582. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00109 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W (1995) DNA repair and mutagenesis ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Glazier VE and Krysan DJ (2018) Transcription factor network efficiency in the regulation of Candida albicans biofilms: it is a small world. Curr.Genet 64:883–888. doi: 10.1007/s00294-018-0804-1 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalir S, McClure J, Pabbaraju K, Southward C, Ronen M, Leibler S, Surette MG, Alon U (2001) Ordering genes in a flagella pathway by analysis of expression kinetics from living bacteria. Science 292:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1058758 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M (2011) A tale of two repressors. J.Mol.Biol 409:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.023 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Reverchon S, Nasser W, Muskhelishvili G (2018) Chromosomal organization of transcription: in a nutshell. Curr.Genet 64:555–565. doi: 10.1007/s00294-017-0785-5 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsky B, Neuert G, van Oudenaarden A (2012) Using gene expression noise to understand gene regulation. Science 336:183–187. doi: 10.1126/science.1216379 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M (2004) A genetic switch: phage lambda revisited. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- Radman M (1999) Enzymes of evolutionary change. Nature 401:866–7, 869. doi: 10.1038/44738 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs AD, Newby RF, Bourgeois S (1970) lac repressor--operator interaction. II. Effect of galactosides and other ligands. J.Mol.Biol 51:303–314. doi: 0022-2836(70)90144-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronen M, Rosenberg R, Shraiman BI, Alon U (2002) Assigning numbers to the arrows: parameterizing a gene regulation network by using accurate expression kinetics. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 99:10555–10560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152046799 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassanfar M and Roberts JW (1990) Nature of the SOS-inducing signal in Escherichia coli. The involvement of DNA replication. J.Mol.Biol 212:79–96. doi: 0022-2836(90)90306-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen-Orr SS, Milo R, Mangan S, Alon U (2002) Network motifs in the transcriptional regulation network of Escherichia coli. Nat.Genet 31:64–68. doi: 10.1038/ng881 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslaver A, Mayo AE, Rosenberg R, Bashkin P, Sberro H, Tsalyuk M, Surette MG, Alon U (2004) Just-in-time transcription program in metabolic pathways. Nat.Genet 36:486–491. doi: 10.1038/ng1348 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]