Abstract

Phencyclidine (PCP) administration is commonly used to model schizophrenia in laboratory animals. While PCP is well-characterized as an antagonist of glutamate-sensitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, its effects on dopamine signaling are not well understood. Here we used whole-cell and cell-attached patch-clamp electrophysiology of substantia nigra dopamine neurons to determine the effects of acute and subchronic PCP exposure on dopamine D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents and evoked burst firing. Acute PCP affected D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents through two apparently distinct mechanisms: a low-concentration dopamine transporter (DAT) inhibition and a high-concentration potassium (GIRK) channel inhibition. Subchronic administration of PCP (5 mg/kg, i.p., every 12 hours for 7 days) decreased sensitivity to low dopamine concentrations, and also enhanced evoked burst firing of dopamine neurons. These findings suggest the effects of PCP on dopaminergic signaling in the midbrain could enhance burst firing and contribute to the development of schizophreniform behavior.

Keywords: Dopamine, mouse, phencyclidine, GIRK, DAT, burst

INTRODUCTION

Subchronic administration of the abused substance and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist phencyclidine (PCP) is commonly used in rodents to model the putative hypoglutamatergic state observed with schizophrenia (Castane et al., 2015). The effects of subchronic PCP are also consistent with findings in humans that repeated abuse of PCP induces schizophreniform symptoms and hyperresponsivity of the mesolimbic dopamine system (Jentsch et al., 1999). The well-characterized antagonism of excitatory NMDA receptors by PCP is difficult to reconcile with observed increases in midbrain dopamine neuron activity. However, PCP may also disrupt inhibitory neurotransmission. Dopamine neurons express D2 autoreceptors on their cell bodies and dendrites that couple to G protein-coupled, inwardly-rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels that hyperpolarize the cell (Beckstead et al., 2004; Lacey et al., 1987; Robinson et al., 2017). Repeated activation of D2 autoreceptors induces long-term depression of inhibitory input and increases dopamine neuron activity (Beckstead and Williams, 2007; Piccart et al., 2015). In vitro, PCP has been reported to display agonist action of D2 receptors in their high-affinity state (Kapur and Seeman, 2002; Seeman and Guan, 2008; Seeman et al., 2005), to inhibit the dopamine uptake transporter (DAT; Schiffer et al., 2003), and to inhibit GIRK channel signaling (Kobayashi et al., 2011). However, binding assays revealed no affinity of three PCP analogues for either the D2 receptor or DAT (Roth et al., 2013) and no stimulatory agonist action for PCP at D2 receptors (Odagaki and Toyoshima, 2006). Thus, the underlying action of PCP on dopamine signaling remains unclear.

Here we used electrophysiological recordings of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in brain slices from adult mice to determine which putative effects of PCP alter dopaminergic signaling. We hypothesized that blockade of DAT or GIRK channels, and/or direct agonist action at D2 autoreceptors by acute or subchronic PCP could depress inhibition of midbrain dopamine neurons and enhance firing activity, in agreement with the hyperdopaminergic state observed in schizophrenia and schizophrenia models. The results indicate a role for altered dopaminergic signaling in subchronic PCP models.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Male DBA/2J mice (Jackson Laboratory) were group-housed on a reverse cycle (lights off 0900-1900), with food and water available ad libitum. Treated mice received PCP (5 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline every twelve hours for seven consecutive days, followed by seven days with no treatment. All experiments were reviewed and approved by the UT Health, San Antonio Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Brain slice electrophysiology

Brain slicing and electrophysiological procedures are described in the supplementary material. In cells from naive animals, we elicited D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents by iontophoresis of dopamine (1M in the pipette). Dopamine was retained with negative current and ejected as a cation with 50–200 ms pulses of +150–220 nA using an ION-100 iontophoresis generator (Dagan). In cells from treated mice, maximal responses to dopamine were elicited with 5 s iontophoretic pulses spaced 5 minutes apart. After another 5 minutes, dopamine (3 μM, then 10 μM) was then bath perfused. Percent effect was calculated as the peak current amplitude in response to dopamine divided by the maximal current amplitude in response to the first iontophoretic pulse, x100%. GABAB receptor-mediated currents were also elicited, using iontophoresis of GABA (1M, pH 4.0). Finally, dopamine neuron burst firing was induced by iontophoresis of D-aspartic acid (800 mM, ejected for 50–200 ms as an anion with a negative pulse) as previously reported (Branch et al., 2013).

Drugs

Kynurenic acid and MK-801 (for slicing), PCP, and dopamine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St-Louis, USA).

Statistical analyses

Data were collected using Axograph 1.3.5 (Axograph Scientific) and LabChart (AD Instruments). Two-way (RM) analyses of variance (ANOVAs) or paired Student’s t-tests were used for between-group comparisons. Tukey’s or Sidak’s post hoc tests were performed subsequent to significant ANOVAs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; α was set a priori at 0.05. Asterisks in the figures refer to posthoc tests, except for the vertical bar in panel 2E which is a significant main effect. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

RESULTS

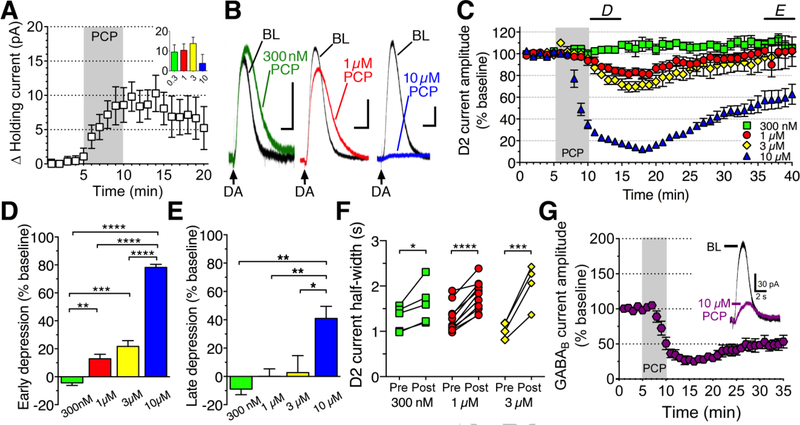

Acute PCP decreases D2 current amplitude

To determine whether PCP affects dopamine cell function we obtained whole-cell voltage clamp (−60 mV) recordings of dopamine neurons from naive mice and bath perfused PCP. Most cells exhibited a slight outward shift in holding current in response to PCP (Figure 1A; n=19 pooled cells), but it did not vary across concentration (0.3–10 μM). To determine the effects of PCP on dopamine signaling we measured D2 autoreceptor, GIRK channel-mediated currents that were elicited by a once-per-minute iontophoresis of dopamine. PCP (0.3–10 μM) was applied to the bath for five minutes (Figure 1B) and the change in peak current amplitude measured (Figure 1C). Middle and high concentrations of PCP depressed current amplitudes, measured as the percent reduction from baseline in peak current amplitude immediately following PCP (1 μM [n=13]: 12.84±3.21%, 3 μM [n=6]: 21.73±4.08%, 10 μM [n=9]: 78.20±2.19%), but not in response to the lowest concentration (300 nM [n=7], −4.36±1.9%, Figure 1D). Two-way RM ANOVA revealed a main effect of concentration (F3,31=120.4, p<0.0001), with significantly larger depression in response to 1, 3, and 10 μM compared to 300 nM (p<0.01, p<0.001 and p<0.0001 respectively), and significantly larger depression in response to 10 μM compared to 1 and 3 μM (p<0.0001). Prolonged effects of PCP, measured as the average % reduction in peak current amplitude between minutes 35–40, were observed at the highest concentration (10 μM: 40.96±8.55% reduction), but not the lower concentrations (300 nM: −8.95±3.9% reduction, 1 μM: 0.11±5.23% reduction, 3 μM: 2.73±12% reduction; Figure 1E). Two-way RM ANOVA indicated a main effect of concentration on sustained depression (F3,25=7.64, p=0.0009), with significantly larger depression in response to 10 μM compared to 300 nM, 1 μM, and 3 μM (p<0.01, p<0.01 and p<0.05 respectively). Moreover, PCP increased the half-width of dopamine currents in every cell recorded (Figure 1F), but this could not be reliably measured for 10 μM PCP due to severely reduced current amplitudes. To determine if PCP effects generalized to other GIRK channel-mediated currents, we also elicited GABAB receptor-, GIRK channel-mediated currents with iontophoresis of GABA. We observed a similar decrease in current amplitudes in response to 10 μM PCP (n=4; Figure 1G). Taken together, the data are consistent with two acute effects of PCP: a mild decrease in dopamine uptake at low concentrations, and an inhibition of GIRK channel signaling at higher concentrations.

Figure 1. Acute PCP inhibits DAT and GIRK channel-mediated currents in dopamine neurons.

A) PCP (0.3–10 μM) bath perfusion produced a small outward current (pooled data shown) that did not appear to be concentration-dependent (inset). B) Sample traces depicting effects of PCP (0.3–10 μM) on D2 autoreceptor currents induced by dopamine iontophoresis (DA, arrows): baseline (BL: black) and after PCP (0.3 μM: green, 1 μM: red, 10 μM: blue). Scale bars: 1 s, 50 pA. C) Time course of PCP effects on D2 autoreceptor-mediated current amplitudes. Horizontal bars: time points analyzed in panels D and E. D) PCP-induced early depression of D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents. E) PCP-induced late depression of D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents. F) PCP (0.3–3 μM) prolonged D2 receptor current half-widths. G) 10 μM PCP inhibited GABAB receptor-, GIRK channel-mediated current amplitudes (sample trace, inset).

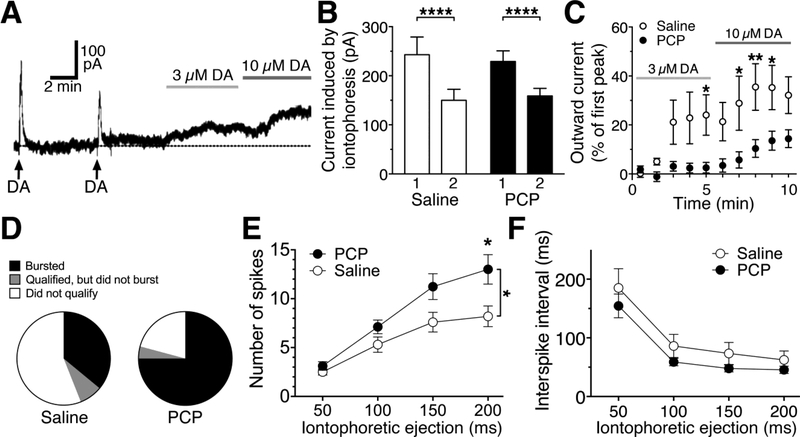

Subchronic PCP decreases D2 autoreceptor sensitivity

To determine the effects of repeated exposure of PCP on D2 autoreceptor currents, we next recorded dopamine neurons from mice that had been treated for seven days with either PCP (5 mg/kg, twice daily) or saline. We first applied two 5s iontophoretic pulses of dopamine at a 5-minute interval, followed another 5 minutes thereafter by 5-minute bath applications of 3 μM and then 10 μM dopamine (Figure 2A). We observed no significant difference between cells from PCP- (n=12) and saline-treated (n=8) mice in maximal peak currents in response to iontophoresis of dopamine (main effect of treatment: F1,28=0.0055, p=0.94, Figure 2B), or in the decrease observed in peak current amplitude on the second application (main effect of application: F1,28=64.2, p<0.0001, interaction: F1,28=1.224, p=0.28, Figure 2B). We did observe a PCP-induced decrease in D2 autoreceptor sensitivity, measured as the current produced by 3 and 10 μM dopamine normalized to the first iontophoretic application (main effect of treatment: F1,18=7.37, p=0.014, main effect of time: F9,162=14.69, p<0.0001, interaction: F9,162=3.78, p=0.0002, Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Subchronic PCP affects dopamine neuron excitability.

A) Sample trace from a saline-treated mouse depicting experimental protocol: two maximal iontophoretic pulses (5s, arrows) separated by 5 minutes, followed by bath perfusion of 3 and 10 μM dopamine (DA). B) Subchronic PCP treatment did not affect maximal current amplitude or the decrease in current amplitude observed with the second iontophoretic pulse. C) Subchronic PCP treatment attenuated currents mediated by bath perfusion of 3–10 μM dopamine. D) Neurons from PCP-treated animals were more prone to bursting (75% burst, 4% qualified but did not burst, and 21% did not qualify) in response to a 100 ms pulse of D-aspartic acid, compared to cells from saline-treated littermates (36% burst, 8% qualified but did not burst, 56% did not qualify). E) Subchronic PCP treatment increased the number of spikes per burst compared to saline treatment. F) Subchronic PCP treatment did not alter interspike intervals compared to cells from saline-treated littermates.

Subchronic PCP enhances dopaminergic burst firing

Midbrain dopamine neurons fire bursts of action potentials in response to glutamate input (Overton and Clark, 1997). To test whether decreased auto-inhibition in dopamine neurons from PCP-treated mice could enhance burst firing, we next simulated the effects of glutamate input to dopamine neurons through iontophoresis of D-aspartic acid. In order to “qualify” for further recording we first required the cell to fire a minimum of 4 spikes in response to a 100 ms iontophoretic pulse. We then tested a range of pulse durations (50–200 ms). Bursts were identified by ≥1 interspike interval <80 ms, as previously described (Branch et al., 2013; Grace and Bunney, 1984). Dopamine neurons from PCP-treated mice exhibited a large proportion of cells that burst in response to 100 ms iontophoresis (18/24, 75%), in comparison to a much smaller portion of cells from saline-treated littermates (9/25, 36%). Moreover, only 5/24 (20.8%) of the cells recorded from PCP-treated animals did not “qualify,” compared to 14/25 (56%) of the cells from saline-treated mice (Figure 2D). Analysis performed specifically on the cells that did burst indicated enhanced firing in PCP-treated mice. Two-way RM ANOVA indicated a significant increase in number of spikes in cells from PCP- (n=17) versus saline- (n=10) treated mice (F1,25=4.23, p=0.0498; Figure 2E). There were also significant effects of iontophoretic pulse duration (F3,75=53.22, p<0.0001) and an interaction between treatment and pulse duration (F3,75=3.77, p=0.01, Figure 2E). Analysis of the shortest interspike interval showed no effect of treatment (F1,25=1.91, p=0.18; Figure 2F), a significant effect of iontophoretic pulse duration (F3,75=46.75, p<0.0001), and no interaction (F3,75=0.14, p=0.93).

DISCUSSION

Interactions between PCP and dopamine D2 receptors have been reported (Balla et al., 2003; Gleason and Shannon, 1997; Kapur and Seeman, 2002; Seeman et al., 2005) but the effects of PCP treatment on dopaminergic signaling in midbrain neurons have not been studied. Here, we investigated the effects of both acute PCP application and subchronic PCP treatment on D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents in substantia nigra dopamine neurons in mouse brain slices.

Acute application of PCP to brain slices from naive mice produced two effects. First, PCP (0.3–3 μM) produced a modest but clear widening of dopamine currents consistent with DAT inhibition (Beckstead et al., 2004). This is consistent with a previously published PET study indicating an interaction between PCP and the cocaine binding site, suggesting possible DAT blockade (Schiffer et al., 2003). This was the only effect observed at 300 nM and actually caused a slight increase in current amplitudes. We went on to reproduce this effect in a separate experiment using D2 receptor inhibitory postsynaptic currents (Supplementary Figure S1; Beckstead et al., 2004). Second, PCP (1–10 μM) also generally inhibited GIRK channel-mediated currents. Bath perfusion of PCP robustly inhibited D2 receptor currents, consistent with previous reports of increased dopamine neuron firing rates and bursting by PCP administered in vivo (French et al., 1993; Svensson et al., 1995). However, this experiment did not distinguish between direct effects at the D2 receptor and those at the GIRK channel. We therefore also used iontophoresis to activate GABAB receptors, which couple to a GIRK conductance that partially overlaps with the one activated by D2 autoreceptors (Beckstead & Williams, 2007). Despite the fact that we had hypothesized PCP agonism at D2 receptors, PCP (10 μM)-induced inhibition of GABAB currents appeared nearly identical to inhibition of D2 currents, strongly suggesting GIRK channels as the locus of effect. One previous study showed that PCP inhibits GIRK channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Kobayashi et al., 2011). Interestingly, those effects were only observed at higher concentrations, suggesting that GIRK channel signaling in dopamine neurons is more sensitive to PCP than in an expression system.

Subchronic PCP treatment is commonly used to model schizophrenia in animals (Castane et al., 2015). D2 autoreceptors provide crucial inhibition of midbrain dopamine neuron firing and downstream dopamine release in the striatum, which is enhanced in schizophrenia (Howes et al., 2012). Attenuated D2 autoreceptor function could therefore contribute to schizophreniform behaviors seen in PCP-treated animals. Indeed, we observed that subchronic PCP treatment decreased D2 autoreceptor-mediated currents, evidenced by an attenuated response to submaximal concentrations of dopamine. We did not, however, observe an effect of treatment on maximal currents. Although multiple possible explanations exist, the decrease in D2 signaling may be caused by decreased coupling efficiency between D2 receptors and GIRK channels, which can be overcome with maximal concentrations of dopamine. Indeed, many psychoactive drugs modulate expression of regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins (Lomazzi et al., 2008) which in turn regulate G-protein coupling to GIRK channels. Alternatively, a decrease in GABAB-GIRK signaling has been noted subsequent to antagonism of NMDA receptors (Workman et al., 2015). However, further investigation is necessary.

We next hypothesized that attenuated inhibition would enhance burst-firing of midbrain dopamine neurons. Indeed, dopamine cells from PCP-treated mice exhibited enhanced burst firing; a larger proportion of cells burst and fired more spikes per burst in response to aspartate iontophoresis. This is in agreement with an earlier report from our lab that showed enhanced burst firing in food-restricted animals that was affected by D2 autoreceptor availability (Branch et al., 2013). However, complementary mechanisms could also contribute to enhanced burst firing. For instance, increased expression of the NR1 NMDA receptor subunit has been observed in the substantia nigra of schizophrenic patients (Mueller et al., 2004). This subunit is critical to the generation of bursts in dopamine neurons (Zweifel et al., 2009), therefore if PCP produces a similar effect it could possibly enhance burst firing as well.

In summary, these results indicate that both acute and subchronic PCP decrease D2 autoreceptor signaling, which could produce some of the schizophreniform behaviors observed in PCP-treated mice. The effects of PCP on the NMDA receptor are well-established. However, the demonstration of PCP effects on D2 autoreceptor signaling in the substantia nigra adds to our knowledge of acute drug mechanisms and may aid in the interpretation of interventional studies that use this model.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 DA032701 and R01 AG052606 to MJB.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 DA032701 and R01 AG052606, both to MJB. NIH had no role in study design, experimental procedures, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- Balla A, Sershen H, Serra M, Koneru R, Javitt DC, 2003. Subchronic continuous phencyclidine administration potentiates amphetamine-induced frontal cortex dopamine release. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead MJ, Grandy DK, Wickman K, Williams JT, 2004. Vesicular dopamine release elicits an inhibitory postsynaptic current in midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron 42, 939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead MJ, Williams JT, 2007. Long-term depression of a dopamine IPSC. J Neurosci 27, 2074–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch SY, Goertz RB, Sharpe AL, Pierce J, Roy S, Ko D, Paladini CA, Beckstead MJ, 2013. Food restriction increases glutamate receptor-mediated burst firing of dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 33, 13861–13872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castane A, Santana N, Artigas F, 2015. PCP-based mice models of schizophrenia: differential behavioral, neurochemical and cellular effects of acute and subchronic treatments. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232, 4085–4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French ED, Mura A, Wang T, 1993. MK-801, phencyclidine (PCP), and PCP-like drugs increase burst firing in rat A10 dopamine neurons: comparison to competitive NMDA antagonists. Synapse 13, 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason SD, Shannon HE, 1997. Blockade of phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion by olanzapine, clozapine and serotonin receptor subtype selective antagonists in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 129, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS, 1984. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: single spike firing. J Neurosci 4, 2866–2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, Stahl D, Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, Kapur S, 2012. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69, 776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR, Elsworth JD, Redmond DE Jr and Roth RH, 1999. Altered frontal cortical dopaminergic transmission in monkeys after subchronic phencyclidine exposure: involvement in frontostriatal cognitive deficits. Neuroscience 90, 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Seeman P, 2002. NMDA receptor antagonists ketamine and PCP have direct effects on the dopamine D(2) and serotonin 5-HT(2)receptors-implications for models of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 7, 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Nishizawa D, Ikeda K, 2011. Inhibition of g protein-activated inwardly rectifying k channels by phencyclidine. Curr Neuropharmacol 9, 244–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey MG, Mercuri NB, North RA, 1987. Dopamine acts on D2 receptors to increase potassium conductance in neurones of the rat substantia nigra zona compacta. J Physiol 392, 397–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomazzi M, Slesinger PA and Lüscher C, 2008. Addictive drugs modulate GIRK-channel signaling by regulating RGS proteins. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29, 544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller HT, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Meador-Woodruff JH, 2004. Expression of the ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits and NMDA receptor-associated intracellular proteins in the substantia nigra in schizophrenia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 121, 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odagaki Y, Toyoshima R, 2006. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated G protein activation assessed by agonist-stimulated [35S]guanosine 5’-O-(gamma-thiotriphosphate) binding in rat striatal membranes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 30, 1304–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton PG, Clark D, 1997. Burst firing in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 25, 312–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccart E, Courtney NA, Branch SY, Ford CP, Beckstead MJ, 2015. Neurotensin Induces Presynaptic Depression of D2 Dopamine Autoreceptor-Mediated Neurotransmission in Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons. J Neurosci 35, 11144–11152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BG, Bunzow JR, Grimm JB, Lavis LD, Dudman JT, Brown J, Neve KA, Williams JT, 2017. Desensitized D2 autoreceptors are resistant to trafficking. Sci Rep 7, 4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Gibbons S, Arunotayanun W, Huang XP, Setola V, Treble R, Iversen L, 2013. The ketamine analogue methoxetamine and 3- and 4-methoxy analogues of phencyclidine are high affinity and selective ligands for the glutamate NMDA receptor. PLoS One 8, e59334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer WK, Logan J, Dewey SL, 2003. Positron emission tomography studies of potential mechanisms underlying phencyclidine-induced alterations in striatal dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 2192–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Guan HC, 2008. Phencyclidine and glutamate agonist LY379268 stimulate dopamine D2High receptors: D2 basis for schizophrenia. Synapse 62, 819–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Ko F, Tallerico T, 2005. Dopamine receptor contribution to the action of PCP, LSD and ketamine psychotomimetics. Mol Psychiatry 10, 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson TH, Mathé JM, Andersson JL, Nomikos GG, Hildebrand BE, Marcus M, 1995. Mode of action of atypical neuroleptics in relation to the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia: role of 5-HT2 receptor and alpha 1-adrenoceptor antagonism. J Clin Psychopharmacol 15, 11S–18S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman ER, Haddick PC, Bush K, Dilly GA, Niere F, Zemelman BV, Raab-Graham KF, 2015. Rapid antidepressants stimulate the decoupling of GABA(B) receptors from GIRK/Kir3 channels through increased protein stability of 14–3-3η. Mol Psychiatry 20, 298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel LS, Parker JG, Lobb CJ, Rainwater A, Wall VZ, Fadok JP, Darvas M, Kim MJ, Mizumori SJ, Paladini CA, Phillips PE, Palmiter RD, 2009. Disruption of NMDARdependent burst firing by dopamine neurons provides selective assessment of phasic dopamine-dependent behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 7281–7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.