Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to identify patients with a high risk of early mortality after acute esophageal variceal bleeding by measuring the C-reactive protein (CRP) level.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 154 consecutive cirrhotic patients admitted with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Differences between categorical variables were assessed by the chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Multivariate logistic regression analyses consisting of clinical laboratory parameters were performed to identify risk factors associated with the 6-week mortality. The discriminative ability and the best cut-off value were assessed by a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results

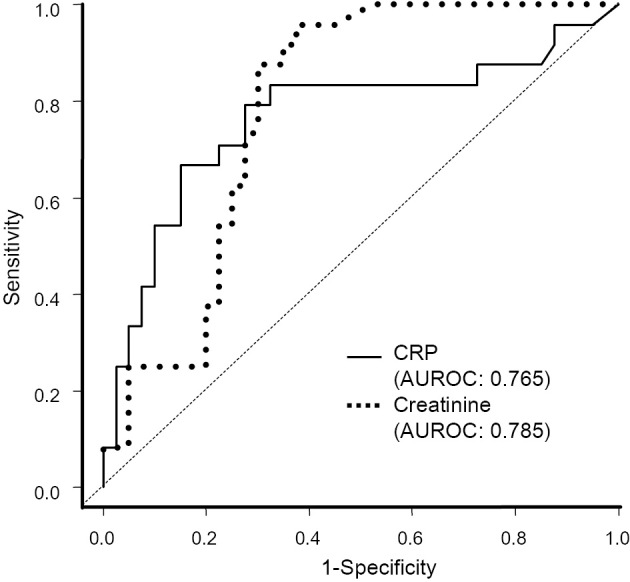

Child-Pugh C patients showed a significantly higher 6-week mortality than Child-Pugh A or B patients (38% vs. 6%, p<0.0001). The 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh C patients was associated with the age (p<0.0001), etiology of cirrhosis (p=0.003), hepatocellular carcinoma (p=0.0003), portal vein thrombosis (p=0.005), baseline creatinine (p=0.0001), albumin (p=0.001), white blood cell count (p=0.038), baseline CRP [p=0.0004; area under the ROC (AUROC)=0.765; optimum cut-off value at 1.30 mg/dL] and bacterial infection (p=0.019). We determined that CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL was an independent predictor for 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh C patients [odds ratio (OR)=8.789; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.080-47.496; p=0.003], along with a creatinine level of 0.71 mg/dL (OR=17.628; 95% CI: 2.349-384.426; p=0.004) (73% mortality if CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL vs. 19% if CRP<1.30 mg/dL, p<0.0001).

Conclusion

In Child-Pugh C patients with esophageal variceal bleeding, a baseline CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL can help identify patients with an increased risk of mortality.

Keywords: acute esophageal variceal bleeding, C-reactive protein, cirrhosis, early mortality

Introduction

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding is a significant life-threatening complication of cirrhosis. Although the mortality during episodes of esophageal variceal bleeding has decreased over the past 3 decades to approximately 20% (1-3), it remains high. Several factors associated with the mortality risk within six weeks after an episode of esophageal variceal bleeding have been identified, including the Child-Pugh class, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, renal failure, bacterial infection, active bleeding at initial endoscopy, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), presence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and hepatic venous pressure gradient (4-9). Among these predictors, the Child-Pugh class has traditionally been used to stratify patients at risk for death, and patients in Child-Pugh class C have a particularly poor prognosis (10, 11).

However, the Child-Pugh classification system has limitations for detecting patients with a high mortality risk, including having a “ceiling effect” with the objective parameters of bilirubin, albumin and prothrombin. It has been shown that the early mortality of patients with decompensated cirrhosis depends largely on events that temporarily worsen or are superimposed on liver failure. The existence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) also appears to be an important prognostic factor. SIRS increases the risk of encephalopathy, renal failure, infection (12-14) and mortality in cirrhosis patients (14, 15). C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute phase protein synthesized in response to cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6. CRP plays a key role in a wide range of inflammatory process and is broadly used for the diagnosis of bacterial infection. However, CRP levels are also elevated in other situations responsible for inflammation, regardless of the presence of bacterial infection (16-18).

In this study, we assessed the utility of the CRP levels in identifying high-risk patients after acute esophageal variceal bleeding.

Materials and Methods

Data collection

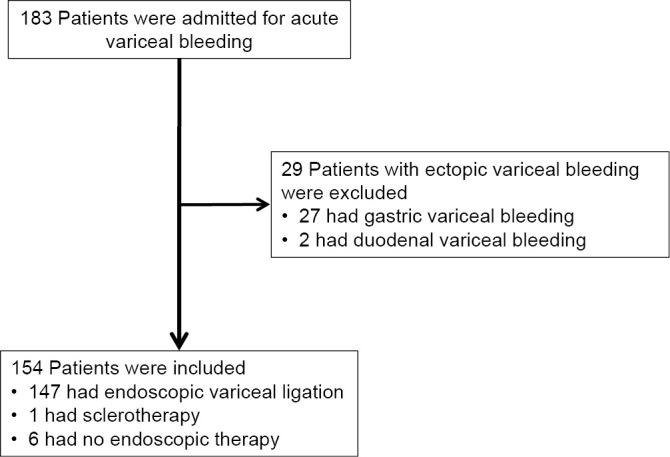

One hundred and eighty-three cirrhotic patients admitted with acute esophageal variceal bleeding between October 2004 and December 2016 at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of Itabashi Chuo Medical Center were included in our study (Fig. 1). Patients bleeding from ectopic varices, such as gastric varices (n = 27) or duodenal varices (n = 2), were not enrolled in the study because of their differing prognosis. We retrospectively analyzed the 154 consecutive patients in our current study. No exclusion criteria were predefined. Baseline clinical and biochemical data of patients were recorded at admission. The Child-Pugh score and the MELD score were calculated from the baseline data. The tumor stage was recorded according to the 7th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/International Union for Cancer Control (UICC) tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification (19).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients admitted with variceal bleeding to our hospital and the selection of the study population.

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. Informed consent had previously been obtained according to the local regulations.

Treatments

An initial endoscopy was performed on all patients within 12 hours of arrival. In patients bleeding from esophageal varices, endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) was performed as first-line therapy. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were prescribed to patients who received EVL for acid suppression. If EVL failed to control the bleeding, the varices were treated with injection sclerotherapy. When necessary, should bleeding fail to be controlled by endoscopic therapy, a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was inserted as a bridge to a new endoscopy (Fig. 1). Patients with hemodynamic instability or a significant drop in hemoglobin were given a packed red blood cell transfusion. Patients underwent endoscopic therapy at one-week intervals as prophylaxis when applicable. Antibiotics were prescribed depending on the patients' clinical condition, laboratory data and physician's preference.

Definitions

The endoscopic findings of esophageal varices were assessed based on the “General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices” prepared by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension (20) and prospectively recorded in the endoscopic database during the study period. The time of inclusion was the moment of admission to our medical center. The primary endpoint of the study was the 6-week mortality, which was defined as death from any cause occurring within six weeks after admission. We chose this outcome because per the Baveno VI consensus workshop, the main treatment outcome in cases of acute variceal hemorrhaging should be the 6-week mortality (21). The follow-up time of six weeks allows comparisons with long-term studies, as most deaths after acute variceal bleeding occur in the first six weeks (5, 11). The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on the clinical, biochemical and imaging findings. HCC was diagnosed based on ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings during admission. PVT was diagnosed based on ultrasound, CT or MRI findings. Bacterial infection, occurring around the index bleeding was defined by one of the following criteria: a fever greater than 38.0°C for more than 12 hours and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascitic fluid polymorphonuclear count ≥250/mm3, positive blood cultures, urinary tract infection, and/or pneumonia on chest radiograph. Other infections were diagnosed according to clinical, radiologic, and bacteriologic data (4). Rebleeding was defined as recurrence of bleeding after initial bleeding control evidenced by new melena or hematemesis, or hemodynamic instability. Under these circumstances, a second endoscopic treatment was performed.

Statistical analyses

Differences between categorical variables were assessed by the chi-square test. Continuous variables were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The selection of a priori variables for the multivariate analysis was based on all variables that showed statistically significant differences on a univariate analysis and in the previous literature (4, 5, 9, 14, 22-25). The candidate variables included the age, creatinine level, CRP level and albumin level. We performed an all-subset selection method to obtain those variables that independently correlated with the 6-week mortality. The discriminative ability was assessed by an area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) curve analysis and the logarithm of the likelihood (LL). The coefficients obtained from the logistic regression analyses were also expressed in terms of the odds of occurrence of an event. The best cut-off value of continuous variables for predicting the 6-week mortality was defined by the Youden index. All analyses were performed using the JMP software program, version 8.0.1 (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan) or EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), which is graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for statistical Computing version 2. 13.0) (26). A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

We evaluated 154 consecutive cirrhotic patients admitted with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. The baseline characteristics of the patients at admission are reported in Table 1. The median age was 65 years (IQR 56-75), with 76% being men. The most common etiology for cirrhosis was alcoholic liver disease (54%) followed by hepatitis C (25%). The median MELD score at admission was 13 (IQR 10-18). The Child-Pugh class for the liver function was class A in 19 patients (12%), class B in 71 patients (46%) and class C in 64 patients (42%). Active variceal bleeding at the initial endoscopy was noted in 74 patients (48%). One hundred and forty-seven patients (95%) received EVL as the initial endoscopic treatment. In one patient, injection sclerotherapy was performed for EVL failure. A Sengstaken-Blakemore tube was inserted into six patients because of a failure to control bleeding by endoscopic therapy (Fig. 1). Fifty-six of 154 patients were administered intravenous antibiotics within 48 hours after the onset of esophageal variceal bleeding. Table 2 shows the main outcomes of the patients. Twenty-nine patients (19%) died within the follow-up period of 6 weeks. The 6-week mortality of patients was 6% among Child-Pugh class A or B patients and 38% among class C patients (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients on Admission, n=154.

| Age (year) | 65 (56-75) |

| Gender (% male) | 117 (76%) |

| Etiology, n (%) | |

| Alcohol | 83 (54%) |

| HCV | 39 (25%) |

| HBV | 8 (5%) |

| Other | 24 (16%) |

| HCC, n (%) | 22 (14%) |

| PVT, n (%) | 15 (10%) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.76 (0.60-1.13) |

| INR | 1.42 (1.21-1.77) |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 138 (136-142) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 2.9 (2.6-3.3) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.4 (0.8-2.6) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 92 (60%) |

| Child-Pugh class A/B/C, n (%) | 19(12%)/71(46%)/64(42%) |

| MELD score | 13 (10-18) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.0 (7.2-10.7) |

| Platelet (×104/µL) | 10.4 (7.4-14.6) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.36 (0.14-0.98) |

| Active bleeding at initial endoscopy, n (%) | 74 (48%) |

| Antibiotics (presence/absence) | 56 (36%)/98 (64%) |

HCV: hepatitis C virus, HBV: hepatitis B virus, HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma, PVT: portal vein thrombosis, INR: international normalized ratio, MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score, CRP: C-reactive protein

Table 2.

Main Outcome of All Cirrhotic Patients with Variceal Bleeding.

| 6-week mortality | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Survival | Death | ||

| All patients, n (%) | 125 (81%) | 29 (19%) | |

| Child-Pugh class, n (%) | |||

| A/B | 85 (94%) | 5 (6%) | <0.0001* |

| C | 40 (63%) | 24 (38%) | |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Clinical characteristics of patients according to the Child-Pugh class and univariate analyses

As shown in Table 3, in Child-Pugh class A or B patients, the etiology of cirrhosis, HCC, PVT, serum sodium level and infection at baseline were significantly associated with the 6-week mortality, whereas the age, creatinine level, albumin level, total bilirubin level, MELD score, hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, CRP level, active bleeding at initial endoscopy and rebleeding within 6 weeks were not. In Child-Pugh class C patients, a higher age, viral cirrhosis, presence of HCC, presence of PVT, elevated creatinine level, lower albumin level, higher WBC count, higher CRP level and infection all had a significant influence on the 6-week mortality. However, the TNM stage, the MELD score, hemoglobin, active bleeding and rebleeding did not differ markedly between Child-Pugh class C patients with and without 6-week mortality. In Child-Pugh class A or B patients, there were only five deaths. Child-Pugh A or B patients were therefore not considered “high-risk”. Only Child-Pugh class C patients were subjected to a subsequent analysis. We investigated Child-Pugh class C patients without HCC in order to exclude the possibility that the existence of HCC could affect the CRP level (Table 4). In Child-Pugh class C patients without HCC, the 6-week mortality was significantly associated with clinical factors in common, like a higher age, elevated creatinine level, lower albumin and higher CRP. A higher WBC count and infection tended to influence the 6-week mortality; however, the difference was not significant. Upon a univariate analysis, the factors associated with the 6-week mortality were almost the same, even after excluding patients with HCC. Therefore, we analyzed Child-Pugh class C patients admitted for acute esophageal variceal bleeding, including patients with HCC, in Fig. 2 and Tables 5-8. The utility of the baseline CRP level for predicting the 6-week mortality was 0.765 [AUROC; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.630-0.900]. The utility of the baseline creatinine level for the same prediction was not significantly different from that of the CRP level: the AUROC was 0.785 (95% CI: 0.674-0.893) (Fig. 2). In Child-Pugh class C patients, optimum cut-off values were calculated as follows: 0.71 mg/dL for creatinine and 1.3 mg/dL for CRP (Fig. 2). Thus, we calculated an optimized age cut-off value of 68 years to distinguish patients with a high risk of 6-week mortality. In addition, a cut-off value of 2.6 g/L was also calculated for the albumin level.

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis for 6-week Mortality according to Child-Pugh Class.

| Child-Pugh A/B | Child-Pugh C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival | n=85 | Death | n=5 | p value | Survival | n=40 | Death | n=24 | p value | |

| Age (year) | 65 | (54-76) | 71 | (61-78) | 0.476 | 58 | (49-67) | 75 | (66-82) | <0.0001* |

| Sex (Male), n (%) | 64 | (75%) | 4 | (80%) | 0.812 | 29 | (73%) | 20 | (83%) | 0.322 |

| Etiology, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Alcohol | 46 | (54%) | 1 | (20%) | 27 | (68%) | 9 | (38%) | ||

| Virus | 22 | (26%) | 4 | (80%) | 0.033* | 7 | (18%) | 14 | (58%) | 0.003* |

| Other | 17 | (20%) | 0 | (0%) | 6 | (15%) | 1 | (4%) | ||

| Previous bleeding, n (%) | 24 | (28%) | 0 | (0%) | 0.165 | 5 | (13%) | 2 | (8%) | 0.605 |

| HCC, n (%) | 6 | (7%) | 3 | (60%) | 0.0003* | 2 | (5%) | 10 | (42%) | 0.0003* |

| TNM stage | ||||||||||

| I-II | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| IIIA-IIIC | 1 | 0 | 0.526 | 2 | 5 | 0.424 | ||||

| IVA-IVB | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||||||

| PVT, n (%) | 4 | (5%) | 2 | (40%) | 0.002* | 1 | (3%) | 6 | (25%) | 0.005* |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.72 | (0.59-1.00) | 1.18 | (0.67-1.60) | 0.192 | 0.68 | (0.56-100) | 1.11 | (0.88-1.64) | 0.0001* |

| INR | 1.27 | (1.15-1.43) | 1.57 | (1.29-1.63) | 0.103 | 1.79 | (1.50-1.99) | 1.73 | (1.33-2.17) | 0.688 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 139 | (138-142) | 133 | (132-136) | 0.003* | 139 | (136-142) | 138 | (133-143) | 0.248 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.2 | (2.9-3.5) | 3.3 | (2.9-3.5) | 0.923 | 2.7 | (2.5-3.0) | 2.4 | (2.1-2.6) | 0.001* |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.0 | (0.8-1.6) | 1.2 | (0.8-2.6) | 0.469 | 2.7 | (1.1-4.8) | 2.6 | (1.6-5.4) | 0.458 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 28 | (38%) | 3 | (60%) | 0.339 | 35 | (88%) | 20 | (83%) | 0.643 |

| MELD score | 11 | (9-14) | 14 | (10-18) | 0.250 | 18 | (14-22) | 19 | (14-26) | 0.317 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.6 | (7.8-11.4) | 9.5 | (6.3-9.5) | 0.205 | 8.8 | (6.8-10.4) | 8.2 | (6.4-9.8) | 0.458 |

| WBC (/µL) | 6,900 | (5,100-9,300) | 8,700 | (4,600-13,850) | 0.515 | 7,800 | (5,125-10,875) | 10,450 | (7,450-15,600) | 0.038* |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.21 | (0.10-0.65) | 0.49 | (0.22-4.06) | 0.121 | 0.41 | (0.03-9.33) | 2.31 | (0.59-4.35) | 0.0004* |

| Active bleeding, n (%) | 38 | (45%) | 1 | (20%) | 0.461 | 19 | (48%) | 16 | (67%) | 0.136 |

| Rebleeding, n (%) | 6 | (7%) | 9 | (0%) | 0.589 | 1 | (3%) | 2 | (8%) | 0.285 |

| Infection, n (%) | 12 | (14%) | 3 | (60%) | 0.008* | 10 | (25%) | 13 | (54%) | 0.019* |

TNM: tumor-node-metastasis, WBC: white blood cell. *Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Table 4.

Univaritate Analysis for 6-week Mortality in Child-Pugh Class C Patients without HCC.

| Survival | n=38 | Death | n=14 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 58 | (49-68) | 69 | (62-81) | 0.004* |

| Sex (Male), n (%) | 27 | (71%) | 11 | (79%) | 0.588 |

| Etiology, n (%) | |||||

| Alcohol | 27 | (71%) | 7 | (50%) | |

| Virus | 6 | (16%) | 6 | (43%) | 0.119 |

| Other | 5 | (13%) | 1 | (7%) | |

| Previous bleeding, n (%) | 5 | (13%) | 1 | (7%) | 0.547 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.68 | (0.56-0.97) | 1.11 | (0.89-1.40) | 0.002* |

| INR | 1.79 | (1.58-2.01) | 2.10 | (1.70-2.86) | 0.065 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 139 | (136-142) | 138 | (136-143) | 0.885 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 2.7 | (2.5-3.0) | 2.4 | (2.2-2.6) | 0.018* |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.6 | (1.0-4.4) | 2.4 | (1.5-5.3) | 0.584 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 33 | (87%) | 13 | (93%) | 0.547 |

| MELD score | 18 | (14-22) | 21 | (16-28) | 0.126 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.8 | (6.6-10.3) | 7.8 | (5.9-10.0) | 0.353 |

| WBC (/µL) | 7,800 | (5,125-10,925) | 11,200 | (6,975-18,975) | 0.056 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.40 | (0.18-0.63) | 1.48 | (0.49-3.03) | 0.009* |

| Active bleeding, n (%) | 19 | (50%) | 12 | (86%) | 0.020* |

| Rebleeding, n (%) | 1 | (3%) | 1 | (7%) | 0.453 |

| Infection, n (%) | 9 | (24%) | 7 | (50%) | 0.068 |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Figure 2.

ROC curves of the model for predicting the six-week mortality in acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Optimum cut-off values of the baseline CRP level and serum creatinine level for distinguishing patients with or without 6-week mortality were defined. The AUROCs of CRP and serum creatinine were not significantly different (p=0.801).

Table 5.

Best Four Models of Logistic Regression Analysis for 6-week Mortality in Child-Pugh Class C Patients with Acute Variceal Bleeding.

| AUROC | Se% | Sp% | -2LL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age≥68 (yeas), CRP≥1.3 (no/yes), Creatinine≥0.71 (no/yes) | 0.902 | 58.3 | 100.0 | 46.8 |

| Age (years), CRP≥1.3 (no/yes), Creatinine≥0.71 (no/yes) | 0.901 | 62.5 | 97.5 | 47.0 |

| Age (years), CRP≥1.3 (no/yes), Albumin<2.6 (no/yes) | 0.890 | 78.0 | 97.5 | 49.0 |

| Age≥68 (years), CRP≥1.3 (no/yes), Albumin<2.6 (no/yes) | 0.879 | 75.0 | 92.5 | 48.1 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.785 | 95.8 | 62.5 | 75.5 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.765 | 79.1 | 72.5 | 73.4 |

AUROC: area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve, Se: sensitivity, Sp: specificity, LL: logarithm of the likelihood

Table 6.

Final Model of Logistic Regression Analysis for 6-week Mortality in Child-Pugh Class C Patients with Acute Variceal Bleeding.

| Variables | Regression coefficient | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.109 | 3.031 | 0.652-15.180 | 0.157 |

| Creatinine | 2.870 | 17.628 | 2.349-384.426 | 0.004* |

| CRP | 2.173 | 8.789 | 2.080-47.496 | 0.003* |

| Constant | -4.021 |

Age, creatinine and CRP were categorized using the cut-off value form the ROC curve. *Statistically significant (p<0.05). CI, confident interval

Table 7.

Association of CRP with 6-week Mortality in Child-Pugh Calss C Patients with Acute Variceal Bleeding.

| Variables | Survial | Death | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| CRP<1.30 mg/dL | 34 (81%) | 8 (19%) | <0.0001* |

| CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL | 6 (27%) | 16 (73%) | |

| CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL, associated with infection | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | 0.793 |

| CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL, nonassociated with infection | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Table 8.

Clinical Characteristics of Child-Pugh Class C Patients with Differential CRP Levels.

| CRP<1.3 mg/dL n=42 |

CRP≥1.3 mg/dL n=22 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 60 (52-69) | 71 (62-82) | 0.003* |

| Sex (Make), n (%) | 30 (71%) | 19 (86%) | 0.298 |

| Etiology, n (%) | |||

| Alcohol | 27 (64%) | 9 (41%) | |

| Virus | 10 (24%) | 11 (50%) | 0.104 |

| Other | 5 (12%) | 2 (9%) | |

| Previous bleeding, n (%) | 6 (14%) | 1 (5%) | 0.236 |

| HCC, n (%) | 3 (7%) | 9 (41%) | 0.001* |

| PVT, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 6 (27%) | 0.002* |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.70 (0.58-1.12) | 0.97 (0.73-1.58) | 0.014* |

| INR | 1.79 (1.53-2.01) | 1.73 (1.21-2.20) | 0.347 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/mL) | 139 (136-142) | 136 (132-142) | 0.025* |

| Albumin | 2.6 (2.4-3.0) | 2.6 (2.4-2.7) | 0.561 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.6 (1.1-4.9) | 2.9 (2.0-5.7) | 0.224 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 36 (86%) | 19 (86%) | 0.943 |

| MELD score | 18 (14-21) | 18(14-24) | 0.339 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.7 (6.6-10.0) | 8.3 (5.9-10.6) | 0.767 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 7.5 (4.9-10.8) | 11.1 (8.5-14.4) | 0.005* |

| Active bleeding, n (%) | 21 (50%) | 8 (36%) | 0.298 |

| Rebleeding, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 0.014* |

| Infection, n (%) | 11 (26%) | 12 (55%) | 0.025* |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Multivariate analyses

Table 5 shows the best four models obtained after the evaluation of the logistic regression analysis using all possible combinations of the candidate variables. The model including age ≥68 years, creatinine level ≥0.71 mg/dL and CRP level ≥1.30 mg/dL showed the best discriminative ability (highest AUROC and lowest -2LL). The CRP level along with the creatinine level were shown to be significant independent predictors of the 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients. Age showed no statistical significance, although it was included in the logistic regression model (Table 6).

Influence of the level and different types of CRP on the 6-week mortality

We investigated the differences in the 6-week mortality according to CRP level. In Child-Pugh C patients, the 6-week mortality was associated with CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL (19% vs. 73%, respectively, for <1.30 and ≥1.30 mg/dL, p<0.0001). Antibiotics were administered to all Child-Pugh C patients with a CRP level ≥1.30 mg/dL associated with clinically evident infection, whereas no patients showing elevated CRP levels that were not associated with clinically evident infection received antibiotics. The 6-week mortality did not differ markedly between the patients showing CRP ≥1.30 mg/dL with or without any clinically evident infection (p=0.793) (Table 7).

Clinical characteristics in patients with different CRP levels

Patients with CRP levels ≥1.30 mg/dL showed a higher age (p=0.003), higher serum creatinine level (p=0.014) and lower serum sodium level (p=0.025) than those with a CRP level <1.30 mg/dL. Patients with CRP levels ≥1.30 mg/dL also more frequently had HCC (p=0.001) and PVT (p=0.002) than those with a CRP level <1.30 mg/dL. Elevated CRP levels were associated with infection (p=0.025) (Table 8).

Discussion

Recent studies on acute esophageal bleeding have proposed predictive factors for identifying high-risk patients after current standard treatment. Augustin et al. considered Child-Pugh class C patients with creatinine >1 mg/dL to be at a high risk for 6-week mortality (5). Amitrano et al. determined that Child-Pugh class C, a WBC >10×109/L and the presence of PVT were the only independent predictors of 5-day failure (22). These studies have shown that the Child-Pugh class remains a strong predictive factor of short-term outcomes. The aim of this study was to identify patients at a high risk of early mortality after acute esophageal variceal bleeding among Child-Pugh class C patients. Our study showed that the baseline CRP level was able to predict the 6-week mortality among Child-Pugh class C patients after acute esophageal variceal bleeding, independent of the usual prognostic criteria, such as MELD scores. A baseline CRP level ≥1.30 mg/dL was the predictor of 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients. Elevated CRP levels were associated with a higher age, the presence of HCC, higher creatinine levels, lower serum sodium levels, rebleeding and the presence of infection.

Other studies have shown that MELD is a significant predictor of short-term mortality at six weeks after acute variceal bleeding (23, 24). The Child-Pugh score and the MELD score are the most commonly used prognostic models in patients with cirrhosis. The MELD score has been shown to be superior to the Child-Pugh score as an index of liver disease severity in patients with chronic liver disease awaiting liver transplantation. Esophageal variceal bleeding is a severe complication in cirrhotic patients. Patients with acute variceal bleeding are at a higher risk developing other complications or dying from hypovolemic shock, infections and the progress of liver failure. However, Tandon et al. found that MELD scores were not as useful as the Child-Pugh class for identifying patients at risk of infection. The most likely explanation for this finding is the inclusion of variables in the Child-Pugh score, like hypoalbuminemia and ascites, which are predictive of infection risk (25). Child-Pugh class C patients are susceptible to infections, and such infections further deteriorate the liver function (27). Another recent study also showed that the Child-Pugh score had a better overall performance in the prediction of 6-week mortality and was better at stratifying the risk of variceal bleeding than the MELD score (28). The MELD score is more objective than the Child-Pugh score, since its calculation is based on the etiology of cirrhosis and three simple laboratory parameters-INR, serum creatinine and bilirubin levels-whereas it may underestimate the severity of liver disease in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and predominant complications of portal hypertension, as it does not include any parameters related to portal hypertension, such as hepatic encephalopathy or ascites (29, 30).

In the present study, small elevations in CRP predicted the risk of 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients after acute esophageal bleeding. CRP is mainly produced in the liver. Although the elevation of CRP is reduced in response to infection or systemic inflammation, the production is maintained even in Child-Pugh class C patients. High CRP levels can be observed even in cirrhotic patients with underlying liver dysfunction in Child-Pugh class C (31, 32). Cervoni et al. reported a significant prognostic impact of elevated CRP on short-term mortality in Child-Pugh score ≥8 cirrhotic patients. Persistently elevated CRP levels in these patients predicted short-term mortality better than infection or clinically-assessed SIRS (33). Systemic inflammation, reflected by elevated CRP, is common in patients with advanced cirrhosis, like Child-Pugh class C and portal hypertension. Inflammatory response activation may be promoted by occult infections associated with bacterial translocation that complicates the increase in the intestinal permeability in these patients (34). Systemic inflammation has been shown to favor serious complications, such as variceal bleeding, encephalopathy and acute-on-chronic liver failure (14, 35, 36). Elevated CRP levels reflect not only infection but also the existence of systemic inflammation. Thus, regardless of the presence of clinically evident infection, elevated CRP levels may have been a predictor of the 6-week mortality after esophageal variceal bleeding in Child-Pugh class C patients in the present study.

The serum creatinine level was also an independent predictor of the 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients in our study. The optimized cut-off value of serum creatinine for the prediction of mortality was 0.71 mg/dL. In a previous study, the model including baseline creatinine ≥1.0 mg/dL showed the best discriminative ability for 6-week mortality in patients after acute variceal bleeding (5). The cut-off values of serum creatinine level in both the present and previous studies were not necessarily high. In patients with cirrhosis, serum creatinine may be an even poorer reflection of the renal function than in those without cirrhosis because of a reduced muscle mass, particularly in patients with severe liver disease. In this setting, the release of creatinine is considerably reduced, and therefore, patients may have a falsely low serum creatinine value (36). Thus, serum creatinine is limited in several respects for the assessment of the renal function in patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, when an increase in serum creatinine is found in a patient with liver disease, it is first necessary to determine whether or not the patients has chronic kidney disease (CKD), acute kidney disease (AKD) or acute kidney injury (AKI). This is crucial for determining the treatment strategies that should be started immediately in cases of AKD or AKI and less urgently in case of CKD (37). Not only the development of AKI, but also the cause of impairment in kidney function is an important prognostic factor; patients with hepatorenal syndrome have worse prognosis compared with that of patients with other causes (38). The prognosis differs markedly according to the clinicopathological condition of kidney dysfunction. We should pay attention to the prediction of early mortality by using the serum creatinine level in decompensated cirrhotic patients after esophageal variceal bleeding.

In Child-Pugh class C patients with CRP levels ≥1.30 mg/dL, variceal bleeding should be considered a fatal event. Indeed, these patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding had a dismal prognosis with a 6 week-mortality of 75%. In these patients, intensive care should always be attempted. Garcia-Pagan et al. reported that, in Child-Pugh class C patients, 10 (67%) of the total 15 patients in the pharmacology plus EVL group died, compared with 3 (19%) of the total 16 patients in the early use of a TIPS (within 72 hours of the initial endoscopy) (early-TIPS) group. Early TIPS may be selected in Europe and North America, as this is the only patient-tailored strategy proven to date to improve the outcome in acute variceal bleeding (11). However, the TIPS procedure is not commonly performed in Japan due to the disadvantages associated with TIPS, such as an increased incidence of encephalopathy, that may not be outweighed by their advantages.

There are several limitations associated with this study. First, our study was conducted at a single center and needs external validation. The baseline CRP proved a powerful tool for predicting the 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients after acute esophageal bleeding. CRP is a simple marker that can be easily checked in patients on admission. We believe that our prognostic model consisting of the Child-Pugh class and CRP level can therefore be applied to any tertiary hospital. Second, although PPIs were administered to patients who received EVL, no vasoactive drug, like somatostatin or terlipressin, and very few secondary prophylaxis agents, like β-blockers, that affect esophageal bleeding were prescribed. Treatment using these drugs is the standard care according to the Baveno consensus workshops and 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (21, 39). However, the management in this study was performed in a manner more typical of Japan than Europe and North America (40). In the same way, antibiotics were instituted only for patients with clinically evident infection and not in all patients as prophylaxis. Finally, this was retrospective study. A retrospective study design can result in some bias due to patient selection. However, 95% of patients in the study cohort underwent EVL. This rate is consistent with the rates of 94-100% in other retrospective, non-clinical trial cohorts in Spain (5) and Japan (41). We therefore feel that this potential bias is reduced in the point of treatment selection and believe that our study cohort well reflects daily urgent endoscopic therapy in patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding arriving at tertiary hospitals. In addition, this study contained 12 (18.9%) HCC patients in Child-Pugh class C patients. A recent study reported that elevated CRP is associated with a dismal prognosis in HCC patients (42). Therefore, we investigated the influence of elevated CRP on the 6-week mortality in Child-Pugh class C patients without HCC and confirmed that, regardless of the presence of HCC, the 6-week mortality was associated with elevated CRP in those patients.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the clinical importance of the baseline CRP level in predicting the 6-week mortality in cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh class C status. Thus, conducting early and simple evaluations using a marker that can be easily measured is useful for identifying high-risk patients after acute esophageal variceal bleeding. The early identification of such patients offers the opportunity to select other treatment options with intensive care before the patient's condition deteriorates.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Sato M, Tateishi R, Yasunaga H, et al. Variceal hemorrhage: analysis of 9987 cases from a Japanese nationwide database. Hepatol Res 45: 288-293, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jairath V, Rehal S, Logan R, et al. Acute variceal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom: patients characteristics, management and outcomes in a nationwide audit. Dis Liver Dis 46: 419-426, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 80: 800-809, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Augustin S, Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, et al. Predicting early mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage based on classification and regression tree analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 1347-1354, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Augustin S, Altamirano J, Gonzalez A, et al. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 1787-1795, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Banares R, et al. Spanish cooperative group for portal hypertension and variceal bleeding. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol 48: 229-236, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. D'Amico G, de Franchis R. Cooperative Study Group. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology 38: 599-612, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moitinho E, Escorsell A, Bandi JC, et al. Prognostic value of early measurements of portal pressure in acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 117: 627-631, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reverter E, Tandon P, Augustin S, et al. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 146: 412-419, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study, Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices: a prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med 319: 983-989, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia-Pagan JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 362: 2370-2379, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, Jalan R. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effect of induced hyperammonia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 40: 247-254, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cazzaniga M, Dionigi E, Gobbo G, Fioretti A, Monti V, Salemo F. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in cirrhotic patients: relationship with their in-hospital outcome. J Hepatol 51: 475-482, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thabut D, Massard J, Gangloff A, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score and systemic inflammatory response are major prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis and acute functional renal failure. Hepatology 46: 1872-1882, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Navasa M, Follo A, Filella X, et al. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: relationship with the development of renal impairment and mortality. Hepatology 27: 1227-1232, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castelli GP, Pognani C, Meisner M, Stuani A, Bellomi D, Sgarbi L. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein during systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis and organ dysfunction. Crit Care 8: R234-R242, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chauveau P, Level C, Lasseur C, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as markers of mortality in hemodialysis patients: a 2-year prospective study. J Ren Nutr 13: 137-143, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lavrentieva A, Kontakiotis T, Lazarids L, et al. Inflammatory markers in patients with severe burn injury. What is the best indicator of sepsis? Burns 33: 189-194, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Springer, New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, et al. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition). Dig Endosc 22: 1-9, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty.. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI consensus workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 63: 743-752, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Manguso F, et al. The effectiveness of current acute variceal bleed treatments in unselected cirrhotic patients: refining short-term prognosis and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol 107: 1872-1878, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bambha K, Kim WR, Pedersen R, Bida JP, Kremers WK, Kamath PS. Predicters of early re-bleeding and mortality after acute variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Gut 57: 814-820, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reverter E, Tandon P, Augustin S, et al. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 146: 412-419, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tandon P, Abraldes JG, Keough A, et al. Risk of bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis and acute variceal hemorrhage, based on Child-Pugh class, and effects of antibiotics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 1189-1196, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cho H, Nagata N, Shimbo T, et al. Recurrence and prognosis of patients emergently hospitalized for acute esophageal variceal bleeding: a long-term cohort study. Hepatol Res 46: 1338-1346, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy -to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48: 452-458, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Christou L, Pappas G, Falagas ME. Bacterial infection-related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 1510-1517, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fortune BE, Garcia-Tsao G, Cialeblio M, et al. ; Vapreotide Study Group. . Child-Turcotte-Pugh class is the best at stratifying risk in variceal hemorrhage: analysis of a US multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol 51: 446-453, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E, Dimitriadou E, et al. MELD vs Child-Pugh and creatinine-modified Child-Pugh score for predicting survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 11: 3099-4104, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park WB, Lee KD, Lee CS, et al. Production of C-reactive protein in Escherichia coli-infected patients with liver dysfunction due to liver cirrhosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 51: 227-230, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bota DP, Van Nuffelen M, Zakariah AN, Vincent JL. Serum levels of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in critically ill patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Lab Clin Med 146: 347-351, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cervoni JP, Thevenot T, Weil D, et al. C-reactive protein predicts short-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 56: 1299-1304, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cirera I, Bauer TM, Navasa M, et al. Baacterial translocation of enteric organisms in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 34: 32-37, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, Jalan R. Systemic inflammation response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 40: 247-254, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cazzaniga M, Dionigi E, Gobbo G, Fioretti A, Monti V, Salemo F. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in cirrhotic patients; relationship with their in-hospital outcome. J Hepatol 51: 475-482, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garcia-Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology 48: 2064-2077, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fagundes C, Barreto R, Guevara M, et al. A modified acute kidney injury classification for diagnosis and risk stratification of impairment of kidney function in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 59: 474-481, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver disease. Hepatology 65: 310-335, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hidaka H, Nakazawa T, Wang G, et al. Long-term administration of PPI reduces treatment failures after esophageal variceal band ligation: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gastroenterol 47: 118-126, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cho H, Nagata N, Shimbo T, et al. Recurrence and prognosis of patients emergently hospitalized for acute esophageal variceal bleeding: a long-term cohort study. Hepatol Res 46: 1338-1346, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sieghart W, Pinter M, Hucke F, et al. Single determination of C-reactive protein at the time of diagnosis predicts long-term outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 57: 2224-2234, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]