Short abstract

Objective

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides important information regarding tumors in the parapharyngeal space (PPS), revealing their origin, whether they are benign or malignant, and their relationships with surrounding structures.

Methods

Twelve tumors in the PPS were completely excised using an endoscopically assisted transoral approach (EATA). The MRI features were analyzed.

Results

Ten pleomorphic adenomas confirmed on postoperative pathological examination had the parotid pedicle sign. A fat space between the tumor and parotid gland may distinguish such a tumor from a tumor arising from a minor salivary gland in the prestyloid space and a tumor arising from the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Both the jugular vein and carotid artery were displaced posteriorly in all 10 cases of pleomorphic adenomas. The principal features of the two schwannomas confirmed on postoperative pathological examination were separation of the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein and anteromedial displacement of the internal carotid artery, suggesting that the tumors originated in the poststyloid space. In this review, 95 tumors were excised by the EATA in the English-language literature.

Conclusions

MRI renders differential diagnosis possible. PPS tumors may be completely excised via an EATA guided by tumor features evident on preoperative MRI.

Keywords: Parapharyngeal space, tumor, transoral approach, endoscopic surgery, magnetic resonance imaging, parotid pedicle sign

Introduction

Tumors in the parapharyngeal space (PPS) are uncommon,1–4 accounting for only 0.5% of all head and neck neoplasms. Approximately 70% to 80% of tumors originating from the PPS are benign.1–4 In general, most tumors in the retrostyloid space are of neurogenic origin, whereas salivary gland tumors, most of which are pleomorphic adenomas, predominate in the prestyloid space.

Several approaches have been developed to excise tumors from the PPS because this space is difficult to access. The anatomy is complex and the surrounding tissue includes vital vascular and nervous structures. The aims of any surgical approach are complete tumor removal without injury to vital structures, preservation of function, a low complication rate, and satisfactory cosmetic results.1–3 The available approaches include a transcervical approach, a transparotid approach, a transcervical-transmandibular approach, and combinations of these approaches. All approaches have particular advantages and limitations.1–3

The transoral approach is the most controversial because of its narrow access, which limits tumor visualization and thus increases the risks of injury to the major neurovascular bundle, tumor spillage, and uncontrolled hemorrhage. Such disadvantages have limited the use of the transoral approach since Goodwin and Chandler5 first introduced the procedure in the 1980s. However, the approach has many advantages, including low risks of injury to the facial and inferior alveolar nerves3,6 and development of salivary fistulae. The method is associated with neither major complications requiring mandibular osteotomy nor cosmetic deformities, and it has a shorter hospitalization time than other approaches.6 Given recent developments in endoscopy and surgical robotics, the surgical scenario of the transoral approach has substantially changed.2,7

Although the transoral surgical approach is promising, some authors have suggested that patients must be carefully selected.3,6 How can surgeons determine preoperatively whether PPS tumors can be excised using the transoral approach? Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide important information regarding PPS tumors, revealing their origin, whether they are benign or malignant, and their relationships with surrounding structures. MRI provides better information about soft than hard tissues.

In the present study, we completely excised PPS tumors using an endoscopically assisted transoral approach (EATA) planned with reference to preoperative MRI features. In this article, we review the relevant English-language literature regarding the use of this approach. We used MEDLINE to run a PubMed/Web of Science search with the key phrases “parapharyngeal space” and “tumor” as well as “parapharyngeal space” and “neoplasm”; we then reviewed all cases treated via the EATA. The findings of this review will further improve this technique and promote its widespread use.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University (Hangzhou City, China), and informed consent was obtained from all included patients. Patients who underwent removal of PPS tumors from June 2012 to July 2017 were retrospectively analyzed. Preoperative MRI was performed on all patients.

MRI protocol

All MRI examinations were performed with the aid of a 3.0-T MRI scanner (Philips Achieva® 3.0T; Royal Philips Electronics, Amsterdam, Netherlands) fitted with a 16-channel head-and-neck coil. Conventional MRI included an axial T1-weighted turbo spin echo (TSE) sequence (slice thickness, 4 mm; 24 slices; intersection gap, 1 mm; repetition time/echo time (TR/TE), 450 ms/10 ms; matrix, 320 × 224; field of view (FOV), 240 × 180 mm) and an axial T2-weighted TSE sequence (slice thickness, 4 mm; 24 slices; intersection gap, 1 mm; TR/TE, 400 ms/10 ms; matrix, 320 × 224; FOV, 240 × 180 mm). A coronal T2-weighted TSE sequence was also employed (slice thickness, 4 mm; 24 slices; intersection gap, 1 mm; TR/TE, 400 ms/10 ms; matrix 320 × 224; FOV, 240 × 220 mm); two signals were acquired, thus covering the larynx. After gadolinium injection, T1-weighted fat-saturated sequences were run in the axial plane (using the parameters employed prior to contrast medium administration) and in the coronal plane (24 slices; slice thickness, 4 mm; intersection gap, 1 mm; TR/TE, 540 ms/9.2 ms; matrix, 320 × 224; FOV, 240 × 220 mm); two signals were acquired using fat suppression.

All imaging data were reviewed by two radiologists who had extensive experience in head and neck imaging and were blinded to the data regarding the primary lesion; they reached a consensus and then reviewed the pathology results. The contour, size, and internal architecture of all lesions were documented.

Surgical technique

All tumors were completely excised using an EATA with the patients under general anesthesia. First, a David’s mouth gag was placed to retract the tongue. The ipsilateral tonsil was excised to expose the surgical view; a vertical incision was made along the bulge that ran from the middle of the hard palate to the lower pole of the tonsil. The mucosa, submucosa, and superior constrictor muscle were cut and divided. The inner, lower, and superior margins of the tumor were gradually (bluntly) separated. Using 0° and 30° endoscopes through a scope that transorally rested on the lip, the lateral margin of the tumor was exposed and separated from the surrounding vital structures (including the parotid gland and internal carotid artery (ICA)) via blunt dissection. All tumors were completely excised without capsule rupture or tumor fragmentation. The surgical field was washed with diluted iodine. The incision was closed layer by layer to form a watertight seal.

Results

Clinical results

In total, 12 patients were included in this study. Of these 12 patients, 9 were male and 3 female with a mean age of 41 years (range, 26–61 years). Their symptoms included the feeling of a foreign body in the throat (16.7%, 2/12), snoring (25.0%, 3/12), an asymptomatic growth detected during a routine checkup (50.0%, 6/12), and throat pain and hoarseness (8.3%, 1/12). All patients had bulges in the ipsilateral oropharyngeal region (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical results of 12 patients with parapharyngeal space tumors

| No. | Age (years) | Sex | Size | Symptoms | Complications | Pathologic result | Blood loss (mL) | Operative time (minutes) | Days as an inpatient | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | M | 3.0 × 5.0 cm | Blocked feeling in the throat | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 30 | 84 | 6 | NED 50 |

| 2 | 34 | M | 5.0 × 4.0 cm | Foreign body feeling in the left throat | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 20 | 67 | 13 | NED 69 |

| 3 | 26 | M | 5.5 × 4.5 × 2.5 cm | Snoring | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 50 | 70 | 7 | NED 44 |

| 4 | 28 | M | 7.0 × 5.0 × 3.5 cm | Swelling in the left throat | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 30 | 94 | 11 | NED 50 |

| 5 | 61 | M | 6.0 × 4.5 × 3.0 cm | Feeling of mucus | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 50 | 89 | 12 | NED 31 |

| 6 | 56 | M | 5.0 × 4.0 × 2.0 cm | Foreign body feeling in the throat | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 20 | 80 | 6 | NED 50 |

| 7 | 38 | F | 8.0 × 6.0 cm | Incidentally discovered right soft palate mass during routine examination | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 200 | 137 | 13 | NED 25 |

| 8 | 45 | M | 6.2 × 3.8 cm | Hoarseness | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 100 | 121 | 5 | NED 12 |

| 9 | 43 | M | 6.0 × 4.5 cm | Snoring | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 100 | 89 | 4 | NED 9 |

| 10 | 38 | F | 5.8 × 3.0 × 3.7 cm | Incidentally discovered right pharyngeal mass | None | Pleomorphic adenoma | 20 | 47 | 5 | NED 8 |

| 11 | 51 | F | 3.0 × 6.0 cm | Incidentally discovered left pharyngeal mass during routine examination | Hoarseness, paralysis of left vocal cord | Schwannoma | 50 | 105 | 14 | NED 30 |

| 12 | 44 | M | 5.0 × 5.3 cm | Throat pain, snoring | Horner’s syndrome | Schwannoma | 100 | 144 | 12 | NED 7 |

M, male; F, female; NED, no evidence of disease

MRI findings

Routine MRI was performed on all 12 patients and showed that all tumors were heterogeneous. On T1-weighted images, five tumors (41.7%) were hypointense and seven (58.3%) were isointense. On T2-weighted images, all 12 tumors (100%) were hyperintense. On gadopentetic acid contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI, four tumors (33.3%) exhibited heterogeneous enhancement, and eight (66.7%) were strongly enhanced (Figure 1).

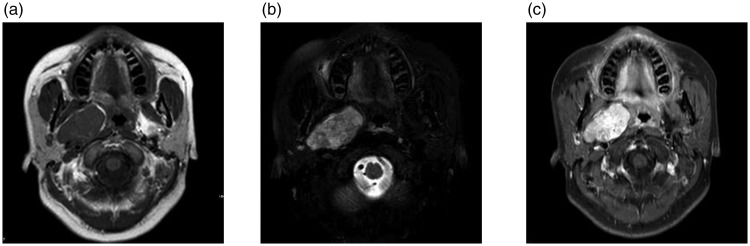

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of Case 7. (a) Axial T1-weighted image showed an isointense mass in the right parapharyngeal space. (b) Axial T2-weighted image showed a hyperintense mass in the right parapharyngeal space. and (c) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showed that the mass was strongly enhanced

Ten pleomorphic adenomas were located in the prestyloid space, displacing both the jugular vein and carotid artery posteriorly. No fat space was present between the adenomas and the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Some fat spaces around the tumors had disappeared. When the residual fat layer between the tumor and pharynx encircled the tumor both anteromedially and posteromedially, the tissue resembled a fatty cap placed on the tumor and was termed the fat cap sign (Figure 2). Extension of part of the tumor to the deep lobe of the parotid gland was termed the parotid pedicle sign (Figure 2) and was present in all pleomorphic adenomas (Figure 2), which were located superficial to the belly of the digastric muscle and shifted that muscle medially (Figure 2).

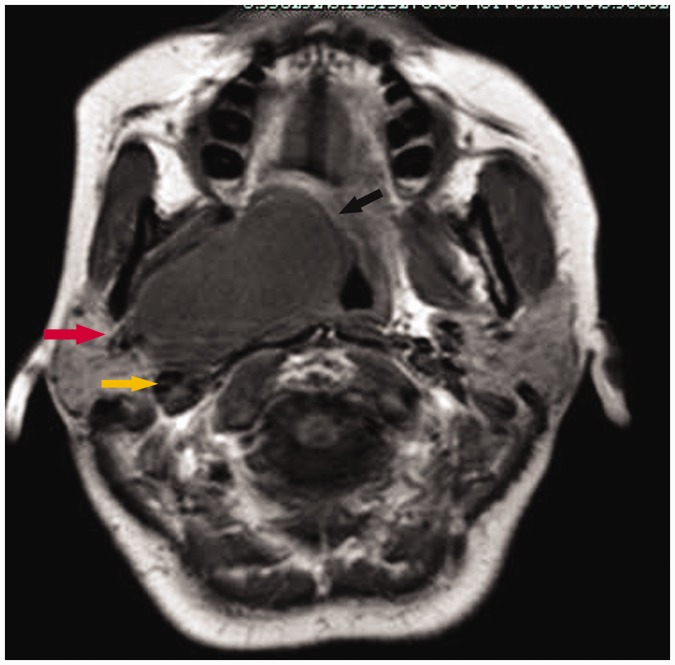

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of a pleomorphic adenomas showed that tumor was located in the prestyloid space (Case 10). An axial T1-weighted image showed that the tumor displaced the carotid artery posteriorly (yellow arrow) and the presence of the fat cap sign (black arrow) and parotid pedicle sign (red arrow)

MRI revealed two solitary oval schwannomas in the retrostyloid space that displaced the ICA anteromedially, thus separating that artery from the internal jugular vein (Figure 3). Two schwannomas were located deep in the posterior region of the digastric muscle and shifted that region laterally (Figure 3). These schwannomas lacked the fat cap and parotid pedicle signs.

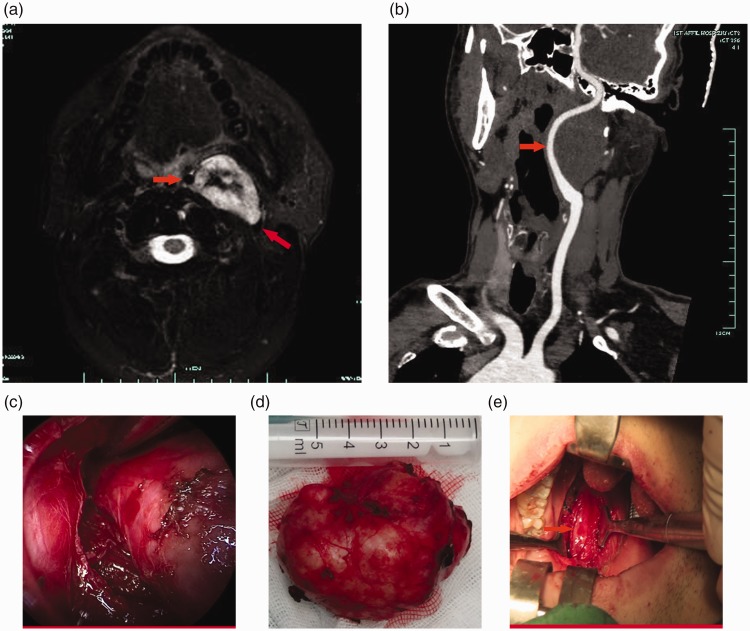

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography angiography, surgical view, tumor sample of Case 11. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging of a schwannoma showed that the tumor was located in the retrostyloid space. The mass was solitary and oval. An axial T1-weighted image revealed that the tumor displaced the internal carotid artery anteromedially (red arrow) and separated the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein (red arrow). (b) Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed that the left internal carotid artery was displaced anteromedially (red arrow). (c) View of the endoscopic-assisted transoral approach. (d) The completely excised tumor. and (e) Left internal carotid artery in the surgical cavity (red arrow)

Surgical results

All patients were planned to undergo surgery based exclusively on their MRI results. All patients underwent surgery via a transoral approach. Frozen section examinations revealed that 10 tumors were pleomorphic adenomas and 2 were spindle cell neoplasms (possibly schwannomas). Postoperative pathologic examinations revealed 10 pleomorphic adenomas and 2 schwannomas. The mean surgical time was 93.9 minutes (range, 47–144 minutes). The mean diameter of the excised tumors was 5.9 cm (range, 5.0–8.0 cm). The mean intraoperative blood loss was 64.2 mL (range, 20–200 mL).

No major complication occurred intraoperatively. The 10 patients with pleomorphic adenomas experienced no postoperative complications. The two patients with schwannomas developed complications: one developed hoarseness because the schwannoma had originated in the left vagus nerve, and the other developed Horner’s syndrome because the schwannoma had possibly arisen from the left cervical sympathetic chain. No conversion to an external approach was required. No patient required a nasogastric tube, and all took fluids orally the first day after surgery. All patients reported only mild oral tenderness (visual analog scale scores, 1–3 of 10). All patents regained normal swallowing function in 7 days.

The mean hospitalization time was 4.8 days after surgery (range, 2–9 days). The mean follow-up time was 32 months (range, 7–69 months). MRI, CT, and physical examination revealed no recurrent lesions or metastasis.

Discussion

Tumors in the PPS are uncommon, representing approximately 0.5% of all head and neck neoplasms; about 80% are benign and 20% are malignant.1–4,6,7 Many approaches have been devised to excise such tumors; however, excision is difficult because of the deep location, complex anatomy, and surrounding vital structures. Riffat et al.8 reviewed 1143 PPS tumors and reported about 70 different histological subtypes, creating difficulties in terms of both diagnosis and management.

The currently available preoperative diagnostic techniques include CT, MRI, angiography, fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), and core needle biopsy (CNB),6,9–13 all of which have advantages and disadvantages.

Both CT and MRI can identify the tumor origin, extent, and type by reference to the relationship between the prestyloid fat pad, the tumor, and the direction of vessel displacement.6,9–13 Generally, MRI yields more useful information than CT.6 If the tumor displaces the fat pad medially and/or anteriorly, this suggests that the tumor arises from the deep lobe of the parotid gland. If the tumor displaces the fat pad laterally, creating a fatty plane between the tumor and the deep lobe of the parotid, the tumor may originate from the minor salivary glands. Primary PPS tumors displace fibroadipose tissue both medially and anteriorly; posteromedial displacement suggests that the tumor arises from the deep lobe of the parotid gland and extends to the PPS.6,9–13 When both the jugular vein and carotid artery are displaced posteriorly, this suggests that the tumor arises from the prestyloid space. Poststyloid tumors usually displace the jugular vein posteriorly and/or laterally and the carotid artery anteriorly and/or medially.6,9–13

In the present report, we used the parotid pedicle sign as an additional differentiating feature. The sign suggests that a tumor arising from the deep lobe of the parotid gland extends into the PPS. All 10 pleomorphic adenomas confirmed on postoperative pathological examination had this sign. A fat space between the tumor and the parotid gland may distinguish such a tumor from a tumor arising from a minor salivary gland in the prestyloid space and a tumor arising from the deep lobe of the parotid gland. The presence of a fat layer between the tumor and the parotid gland indicates that the tumor arises in a minor salivary gland.12 Both the jugular vein and carotid artery were displaced posteriorly in all 10 patients with pleomorphic adenomas. The principal features of the two schwannomas confirmed on postoperative pathological examination were separation of the ICA and internal jugular vein and displacement of the ICA anteromedially, suggesting that the tumors originated in the poststyloid space. Preoperative MRI reveals the ICA position that is expected during surgery. After resection of the ipsilateral tonsils, the ICA was meticulously identified, dissected, and protected. We identified the distance between the ICA and pleomorphic adenoma in the PPS according to previous operative MRI, CT, or CT angiography; the pulse of the ICA under endoscopy during the surgery; and our personal experience. All tumors were completely excised with no intraoperative complications. The parotid pedicle and fat cap signs and the direction in which the posterior portion of the digastric muscle runs laterally may be useful in terms of differential diagnosis.

The preoperative yield of FNAC specimens and CNB specimens may be valuable in patients with PPS tumors. However, whether FNAC has any useful role in the preoperative evaluation of PPS tumors remains unclear.6,11 Some authors have suggested that preoperative biopsy may not be necessary if imaging indicates a benign tumor.6,11 At present, however, FNAC remains a feasible and widely accepted diagnostic workup for PPS tumors.

Surgery must fulfill two criteria: complete tumor excision under good visualization and minimal functional and cosmetic adverse effects.1–4,6,7,9–20 The transoral approach remains the most controversial, and historically, it was rather poorly applied. Its limitations include a poor view, rendering exposure of major neurovascular structures difficult; possible capsule disruption and tumor spillage; incomplete tumor removal; uncontrollable blood leakage from great vessels; and facial nerve injury. However, the clinical situation has changed significantly with the advent of endoscopy and surgical robotics. These techniques may overcome the shortcomings of the traditional approach and exploit its advantages.

We reviewed the English-language literature using MEDLINE, with which we performed a PubMed/Web of Science search employing the key phrases “parapharyngeal space” and “tumor” as well as “parapharyngeal space” and “neoplasm.” We then identified all articles in which tumors were excised transorally. In 1950, Ehrlich21 first introduced this approach to excise mixed pterygomaxillary tumors. The right external carotid artery was intraoperatively ligated. Goodwin and Chandler5 reported that the McElroth series of 112 parapharyngeal tumors were successfully excised via ligation of the ipsilateral carotid artery. Ferlito et al.22 recommended addition of tracheotomy and ipsilateral carotid artery ligation when the transoral approach was employed. Thus, the approach became abandoned, being replaced by the transcervical approach because it resulted in fewer major injuries and complications. In 1988, Goodwin and Chandler5 first used the procedure to treat PPS tumors (pleomorphic adenomas) of the parapharyngeal space.

To the best of our knowledge, the first relevant report describing the use of endoscopy to excise PPS tumors by an EATA is the 2014 report by Chen et al.23 In total, 95 PPS tumors excised using an EATA have been described in the English-language literature (including our present series)2,3,6,23–29 (Table 2). The patients comprised 54 males and 38 females (n = 92) with 81 tumors and 10 nontumoral masses (4 cysts, 2 Castleman masses, 3 fibrotic tissues, and 1 marginal-zone follicular hyperplastic mass). Of the 81 tumors, 76 (93.8%) were primary PPS tumors and 5 were secondary malignant tumors (4 metastases of papillary thyroid carcinomas invading the PPS and 1 lymphatic metastasis of a phosphate urinary mesenchymal tissue tumor). Of the 76 primary PPS tumors, 74 were benign (97.4%) [37 pleomorphic adenomas (50.0%), 22 schwannomas (29.7%), 5 hemangiomas (6.8%), 4 lipomas (5.4%), 3 Warthin tumors (4.0%), 1 basal cell adenoma (1.4%), 1 fibroma (1.4%), and 1 osteoma (1.4%)] and 2 were malignant (2.6%) (1 cystic carcinoma and 1 myoepithelial carcinoma). The mean tumor diameter was about 5.1 cm (range, 2.0–8.0 cm; tumor diameters were recorded in 41 cases). The mean operative time was 118.3 min (range, 47–480 min; data from 73 cases). The mean estimated blood loss was 60.8 mL (range, 10–1800 mL; data from 64 cases). The average hospital stay was 6.2 days (range, 2–14 days; data from 75 cases). In total, 94.7% of all tumors (90/95) were excised by employing an EATA. No patient required tracheotomy. Five operations were converted to open transcervical approaches.3,28 The complication rate was 27.4% (26/95): complications included pharyngeal dehiscence (n = 2),2 tumor fragmentation (n = 11),2,6,25,26 laryngeal palsy (n = 5),27,28 Horner’s syndrome (n = 3),27 lip/tongue numbness (n = 1),27 a mouth-opening limitation (n = 1),27 a temporary mouth corner deviation (n = 1),27 effusion (n = 1),28 soft palate necrosis (n = 1),28 and secretory otitis media (n = 1).28 One case of pharyngeal dehiscence resolved completely after conservative treatment, and the other required further surgery. All other complications healed spontaneously. The mean follow-up time was only 22.0 months (n = 76; range, 1–60 months). No primary tumor recurrence was noted. We completely excised all tumors with no intraoperative complications (maximum tumor dimensions, 8.0 × 6.0 cm; mean, 5.9 × 3.7 cm). One tumor (that of Case 12; a schwannoma located between the lateral ICA and the inner internal jugular vein) was resected in a piecemeal manner. We agree with Dallan et al.2 and De Virgilio et al.30 that tumors should be debulked and then dissected along the capsule to avoid injury to surrounding vital structures. However, such an approach is useful only in selected patients undergoing operations by experienced surgeons. No operation was converted to an external approach in the present study. The mean surgical time, intraoperative blood loss, and hospitalization time were similar to those reported above.

Table 2.

Tumors in the PPS excised by an EATA in the English-language literature

| Clinical data | n* (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | 92 |

| Female | 38 (41.3) |

| Male | 54 (58.7) |

| Site | 81 |

| Primary in PPS | 76 (93.8) |

| Metastases | 5 (6.2) |

| Pathological type of primary PPS tumors | 76 |

| Benign tumors | 74 (97.4) |

| Pleomorphic adenomas | 37 (48.7) |

| Schwannomas | 22 (28.9) |

| Hemangioma | 5 (6.6) |

| Lipomas | 4 (5.3) |

| Warthin tumors | 3 (3.9) |

| Basal cell adenoma | 1 (1.3) |

| Fibroma | 1 (1.3) |

| Osteoma | 1 (1.3) |

| Malignant tumors | 2 (2.6) |

| Cystic carcinoma | 1 (1.3) |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | 1 (1.3) |

| Surgical approach | 95 |

| EATA | 90 (94.7) |

| Conversion to open approach | 5 (5.3) |

| Complications | 26 (27.4) |

| Tumor fragmentation | 11 (42.3) |

| Laryngeal palsy | 5 (19.2) |

| Horner’s syndrome | 3 (11.5) |

| Pharyngeal dehiscence | 2 (7.7) |

| Lip/tongue numbness | 1 (3.8) |

| Mouth-opening limitation | 1 (3.8) |

| Temporary mouth corner deviation | 1 (3.8) |

| Effusion | 1 (3.8) |

| Soft palate necrosis | 1 (3.8) |

| Secretory otitis media | 1 (3.8) |

*Numbers of patients available from the literature

PPS, parapharyngeal space; EATA, endoscopically assisted transoral approach

The advantages of endoscopically assisted approaches include the lack of any need for an external incision (eliminating scarring), a short hospital stay, minimal blood loss, and little postoperative pain. However, illumination is poor, rendering maneuverability difficult; this is possibly associated with capsule disruption, tumor spillage and/or incomplete removal, uncontrollable blood loss from great vessels, and facial nerve injuries. Compared with the traditional transoral approach, the EATA has the advantages of adequate illumination and a wide, direct operative field allowing efficient and safe minimally invasive surgery. These advantages reduce the risks of serious complications, damage to surrounding vital structures, uncontrolled bleeding, and tumor spillage. The EATA also offers the advantages of tactile feedback and the possibility that surgery can be performed using a four- or five-handed technique; however, the costs are reduced surgical precision and operation within a bidimensional environment.2 Any residual tumor tissue can be endoscopically detected after the operation and removed.29 Some operations are converted to open transcervical approaches.3,28

Conclusions

MRI renders differential diagnosis possible. PPS tumors may be completely excised via an EATA guided by tumor features evident on preoperative MRI. The EATA is a promising surgical technique.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Dallan I, Seccia V, Muscatello L, et al. Transoral endoscopic anatomy of the parapharyngeal space: a step-by-step logical approach with surgical considerations. Head Neck 2011; 33: 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallan I, Fiacchini G, Turri-Zanoni M, et al. Endoscopic-assisted transoral-transpharyngeal approach to parapharyngeal space and infratemporal fossa: focus on feasibility and lessons learned. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 273: 3965–3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WL, Fan S, Huang ZQ, et al. Endoscopy-assisted transoral versus endoscopy-assisted transcervical minimal incision plus mandibular osteotomy approach in resection of large parapharyngeal space tumors. J Craniofac Surg 2017; 28: 976–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu F, Tagliabue M, Giugliano G, et al. From transmandibular to transoral robotic approach for parapharyngeal space tumors. Am J Otolaryngol 2017; 38: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin WJ, Jr, Chandler JR. Transoral excision of lateral parapharyngeal space tumors presenting intraorally. Laryngoscope 1988; 98: 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iseri M, Ozturk M, Kara A, et al. Endoscope-assisted transoral approach to parapharyngeal space tumors. Head Neck 2015; 37: 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekeny JR, Ozer E. Transoral robotic surgery frontiers. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 2: 130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riffat F, Dwivedi RC, Palme C, et al. A systematic review of 1143 parapharyngeal space tumors reported over 20 years. Oral Oncol 2014; 50: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stambuk HE, Patel SG. Imaging of the parapharyngeal space. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008; 41: 77–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chijiwa H, Mihoki T, Shin B, et al. Clinical study of parapharyngeal space tumours. J Laryngol Otol 2009; 123: 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimitrijevic MV, Jesic SD, Mikic AA, et al. Parapharyngeal space tumors: 61 case reviews. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 39: 983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iglesias-Moreno MC, López-Salcedo MA, Gómez-Serrano M, et al. Parapharyngeal space tumors: fifty-one cases managed in a single tertiary care center. Acta Otolaryngol 2016; 136: 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Som PM, Sacher M, Stollman AL, et al. Common tumors of the parapharyngeal space: refined imaging diagnosis. Radiology 1988; 169: 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantsopoulos K, Müller S, Agaimy A, et al. Extracapsular dissection in the parapharyngeal space: benefits and potential pitfalls. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017; 55: 709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eida S, Sumi M, Sakihama N, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient mapping of salivary gland tumors: prediction of the benignancy and malignancy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 116–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshino N, Yamada I, Ohbayashi N, et al. Salivary glands and lesions: evaluation of apparent diffusion coefficients with split-echo diffusion-weighted MR imaging-initial results. Radiology 2001; 221: 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yologlu Z, Aydin H, Alp NA, et al. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of parotid masses. Preliminary results. Saudi Med J 2016; 37: 1412–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yerli H, Aydin E, Haberal N, et al. Diagnosing common parotid tumours with magnetic resonance imaging including diffusion-weighted imaging vs fine-needle aspiration cytology: a comparative study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2010; 39: 349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahab R, Heliwell T, Jones AS. How we do it: a series of 114 primary pharyngeal space neoplasms. Clin Otolaryngol 2005; 30: 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habermann CR, Arndt C, Graessner J, et al. Diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging of primary parotid gland tumors: is a prediction of different histologic subtypes possible? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 591–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrlich H. Mixed tumors of the pterygomaxillary space; operative removal; oral approach. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1950; 3: 1366–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferlito A, Pesavento G, Recher G, et al. Assessment and treatment of neurogenic and non-neurogenic tumors of the parapharyngeal space. Head Neck Surg 1984; 7: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen WL, Wang YY, Zhang DM, et al. Endoscopy-assisted transoral resection of large benign parapharyngeal space tumors. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 52: 970–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Gong S, Lu Y, et al. Endoscopy-assisted transoral resection of parapharyngeal space tumors: a retrospective analysis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015; 71: 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li SY, Hsu CH, Chen MK. Minimally invasive endoscope-assisted trans-oral excision of huge parapharyngeal space tumors. Auris Nasus Larynx 2015; 42: 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaslikaya S, Koca CF, Toplu Y, et al. Endoscopic transoral resection of parapharyngeal osteoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016; 74: 2329.e1–2329.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan S, Lin SG, Zhang HQ, et al. A comparative study of the endoscopy-assisted transoral approach versus external approaches for the resection of large benign parapharyngeal space tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2017; 123: 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Li WY, Yang DH, et al. Endoscope-assisted transoral approach for parapharyngeal space tumor resection. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017; 130: 2267–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi X, Tao L, Li X, et al. Surgical management of primary parapharyngeal space tumors: a 10-year review. Acta Otolaryngol 2017; 137: 656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Virgilio A, Park YM, Kim WS, et al. Transoral robotic surgery for the resection of parapharyngeal tumour: our experience in ten patients. Clin Otolaryngol 2012; 37: 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]