Abstract

Background:

Most prospective studies involving individuals receiving maintenance dialysis have been small, and many have had poor clinical translatability. Research relevance can be enhanced through stakeholder engagement. However, little is known about dialysis clinic stakeholders’ perceptions of research participation and facilitation. The objective of this study was to characterize the perspectives of dialysis clinic stakeholders (patients, clinic personnel, and medical providers) on: (1) research participation by patients and (2) research facilitation by clinic personnel and medical providers. We also sought to elucidate stakeholder preferences for research communication.

Study Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting & Participants:

7 focus groups (59 participants: 8 clinic managers, 14 nurses/patient care technicians, 8 social workers/dietitians, 11 nephrologists/advanced practice providers, and 18 patients/care partners) from 7 North Carolina dialysis clinics.

Methodology:

Clinics and participants were purposively sampled. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed.

Analytical Approach:

Thematic analysis.

Results:

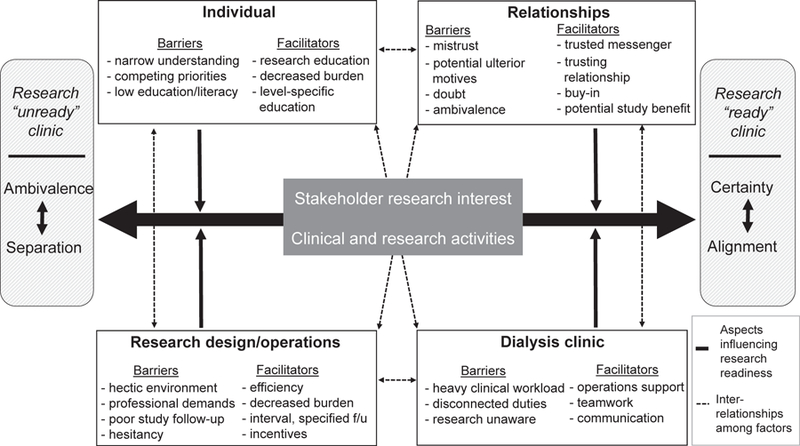

We identified 11 themes that captured barriers to and facilitators of research participation by patients and research facilitation by clinic personnel and medical providers. We collapsed these themes into 4 categories to create an organizational framework for considering stakeholder (narrow research understanding, competing personal priorities, and low patient literacy and education levels), relationship (trust, buy-in, and altruistic motivations), research design (convenience, follow-up, and patient incentives), and dialysis clinic (professional demands, teamwork, and communication) aspects that may affect stakeholder interest in participating in or facilitating research. These themes appear to shape the degree of research readiness of a dialysis clinic environment. Participants preferred short research communications delivered in multiple formats.

Limitations:

Potential selection bias and inclusion of English-speaking participants only.

Conclusions:

Our findings revealed patient interest in participating in research and clinical personnel and medical provider interest in facilitating research. Overall, our results suggest that dialysis clinic research readiness may be enhanced through increased stakeholder research knowledge and alignment of clinical and research activities.

The quality and quantity of published research in kidney disease generally lags behind that of other disciplines.1,2 Clinical trials among individuals receiving maintenance dialysis often have low patient recruitment, incomplete protocol adherence, and poor clinical practice translatability.2,3 These challenges, among others, have contributed to a paucity of high-quality data to inform clinical guidelines and few proven interventions to ameliorate the unacceptably poor outcomes experienced by individuals receiving dialysis.

In recent years, there have been efforts to broaden stakeholder engagement in dialysis research to inform study outcomes and enhance clinical trial relevance and reliability. The Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) initiative has generated a patient-, care partner–, and professional-prioritized list of consensus hemodialysis outcomes.4 This initiative represents progress in dialysis stakeholder engagement, but additional work in aspects of research beyond outcome selection is needed. For example, little is known about dialysis stakeholders’ perceptions of research participation and facilitation.

Acknowledgment of key stakeholder competing priorities and workplace challenges are central to establishing successful research partnerships.5 Research facilitation barriers may arise if clinic environments are not considered when developing study protocols. In the US dialysis delivery system, research oversight is typically centralized at the dialysis provider corporate level. However, research activities take place at local clinics that have their own stakeholders, including clinic managers, nurses, patient care technicians (PCTs), social workers, dietitians, patients, care partners, and medical providers (nephrologists and advanced practice providers). Better understanding of these diverse stakeholders’ research-related perceptions may facilitate improved research participation and facilitation, ultimately enhancing research quality. To begin to address this knowledge gap, we undertook exploratory focus groups to characterize perspectives of dialysis clinic stakeholders (patients, clinic personnel, and medical providers) regarding: (1) patient participation in research and (2) clinic personnel and medical provider facilitation of research in dialysis clinics. We also sought to elucidate stakeholder preferences for research-related communication materials.

Methods

Overview

We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ; Table S1).6 The study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (16–2479). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participant Selection and Setting

Seven dialysis clinic stakeholder–specific focus groups were conducted from November 2016 through February 2017: patients/care partners (n = 2 groups), nurses/PCTs (n = 2 groups), clinic managers (n = 1 group), social workers/ dietitians (n = 1 group), and medical providers (n = 1 group). Participants were recruited from a convenience sample of 7 North Carolina dialysis clinics (Table 1). We strove for clinic diversity and selected clinics based on location (urban vs rural), modality offerings (in-center hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and home hemodialysis), size, and academic affiliation status. Participant recruitment methods included dialysis clinic fliers, announcements at clinic personnel meetings, e-mail, and in-person dialysis clinic interactions. Iterative purposive sampling was used to capture a range of participant characteristics (age, education, dialysis modality, and prior research experience). The target focus group size was 8 participants, with an acceptable size of 6 to 12 participants. We recruited up to 12 participants per group to allow for nonattendance.

Table 1.

Participating Dialysis Clinic and Surrounding Area Characteristics

| Characteristic | Descriptiona |

|---|---|

| Dialysis clinic (n = 7) | |

| No. of hemodialysis stations | 22 [13–41]; (10–43) |

| No. of hemodialysis patients | 78 [49–120]; (32–157) |

| No. of peritoneal dialysis patients | 34 [25–57]; (25–57)b |

| No. of home hemodialysis patients | 5 [3–26]; (3–26)b |

| For-profit statusc | 7 (100%) |

| University-affiliated | 6 (86%) |

| Nurse to patient ratio | 10:1–14:1 |

| PCT to patient ratio | 4:1 |

| Certification date | September 1976-June 2014 |

| Clinic municipality (n = 6) | |

| Population | 15,487 [7,887–29,094]; (3,743–731,424) |

| Black, % | 20.0 [19.1–27.6]; (10.1–35.0) |

| Hispanic, % | 13.5 [8.9–25.6]; (6.0–49.8) |

| Below poverty level, % | 12.2 [8.7–17.0]; (8.5–20.4) |

| Clinic county (n = 5) | |

| County population, per square mile | 336.2 [227.0–356.5]; (93.1–1,755.5) |

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage) and values for continuous variables, as median [interquartile range]; (range).

Abbreviations: PCT, patient care technician; LDO, large dialysis organization.

Data taken from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Dialysis Facility Compare21 and US Census Bureau, 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates.22

Based on 3 clinics.

Six clinics are university and LDO joint ventures and 1 clinic is LDO owned and operated.

Dialysis patients and care partners were eligible to participate if they had been receiving dialysis for 3 or more months or were care partners of patients receiving dialysis for 3 or more months. Individuals with cognitive impairment were excluded. Outpatient dialysis nurses, PCTs, social workers, dietitians, and medical providers (physicians and advanced practice providers) were eligible to participate if they had 1 or more years of dialysis experience. All participants were 18 years or older and English speaking. Participants were reimbursed for time and transportation.

Given the exploratory nature of the study and intent to capture diverse perspectives, we did not evaluate thematic saturation by stakeholder type. Due to low representation of home therapies nurses, patients, and care partners in the initial focus groups, we conducted additional nurse/PCT and patient/care partner groups with oversampling of the under-represented groups. The additional groups did not uncover new themes.

Data Collection

We drafted a focus group moderator guide based on literature review and research team discussions. The guide was finalized after input from 10 multidisciplinary stake-holders (academic and community nephrologists, dialysis clinic personnel, corporate dialysis executives, clinical research organization employees, patients, and care partners). Moderator guide topics included research knowledge and perceptions, research barriers, ideas for increasing interest in research participation and facilitation, and research education and communication preferences (Table S2).

Focus groups were led by an experienced moderator (J.H.N.) who had no prior contact with participants. The focus groups were semistructured, and the moderator asked questions to encourage discussion among participants. Groups lasted 90 to 120 minutes and took place in dialysis clinic conference rooms. Focus groups were audiorecorded and professionally transcribed. A research assistant took notes on group dynamics and participant nonverbal body language. Participant characteristics were self-reported.

Data Analysis

Transcribed interviews were entered into ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software. Thematic analysis and principles of grounded theory were used to guide coding and develop themes and a thematic schema.7–9 Thematic analysis is a systematic approach to analyzing textual data that is iterative and not bound to theoretical paradigms.8,9 Three authors (J.H.N., A.D., and J.E.F.) independently coded the transcripts and developed preliminary code lists. A central codebook was used to identify discrepancies and generate discussion among coders. The codebook was revised based on author consensus to capture all relevant themes and concepts. Through iterative discussions, the authors collated the codes into potential themes and used the software to gather relevant quotations. The authors identified conceptual links and patterns through an iterative theme comparison process and ultimately developed a thematic schema linking themes into a theoretical model for enhancing dialysis clinic research readiness.10,11 We provided preliminary results summaries to participants within 4 weeks of each group to collect feedback and provide follow-up (per participants’ requests for research follow-up).

Results

Participant Characteristics

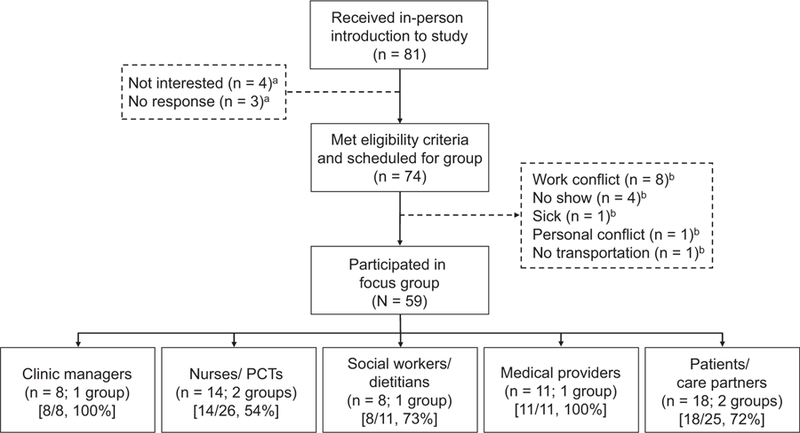

Table 2 displays participant characteristics by stakeholder type. The 7 focus groups involved 59 participants. The overall participation rate was 73%, with stakeholder-specific participation rates ranging from 54% for nurses/ PCTs to 100% for clinic managers and medical providers (Fig 1). Mean participant age was 47.2 ± 12.2 (range, 24–72) years; 37 (62.7%) were women, and 24 (40.7%) were black. Of the 59 participants, 13 (22.0%) had prior research experience. Clinic personnel research experience included study drug administration, blood draws, and patient recruitment. Patient research experience included participation in pharmaceutical trials and interview studies.

Table 2.

Focus Group Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Dialysis patients and care partners (n = 18) | |

| Participant type | |

| Patient | 16 (89%) |

| Care partner | 2 (11%) |

| Age, y | 57 (36–72) |

| Female sex | 6 (33%) |

| Race | |

| White | 4 (22%) |

| Black | 14 (78%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 3 (17%) |

| High school or GED | 5 (28%) |

| Some college | 4 (22%) |

| ≥4 y college | 6 (33%) |

| Dialysis vintage, y | |

| ≤1 | 4 (22%) |

| 2–5 | 8 (44%) |

| ≥6 | 6 (34%) |

| Modality type | |

| In-center hemodialysis | 11 (61%) |

| Home hemodialysis | 4 (22%) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 3 (17%) |

| Prior research experience | 6 (33%) |

| Dialysis nurse and patient care technicians (n = 14) | |

| Participant type | |

| Nurse | 6 (43%) |

| Patient care technician | 8 (57%) |

| Age, y | 42 (24–61) |

| Female sex | 11 (79%) |

| Race | |

| White | 5 (36%) |

| Black | 8 (57%) |

| Other | 1 (7%) |

| Time in role, y | 9 (1–27) |

| Prior research experience | 1 (7%) |

| Dialysis clinic managers (n = 8) | |

| Age, y | 43 (27–65) |

| Female sex | 7 (88%) |

| Race | |

| White | 7 (87%) |

| Black | 1 (13%) |

| Other | 0 |

| Time in role, y | 4 (1–8) |

| Prior research experience | 4 (50%) |

| Dialysis social workers and dietitians (n = 8) | |

| Participant type | |

| Social worker | 5 (62%) |

| Dietitian | 3 (38%) |

| Age, y | 45 (32–62) |

| Female sex | 7 (88%) |

| Race | |

| White | 8 (100%) |

| Black | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Time in role, y | 11 (5–18) |

| Prior research experience | 1 (13%) |

| Dialysis medical providers (n = 11) | |

| Participant type | |

| Physician | 9 (82%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 (18%) |

| Age, y | 40 (32–68) |

| Female sex | 6 (55%) |

| Race | |

| White | 4 (36%) |

| Black | 1 (9%) |

| Other | 6 (55%) |

| Time in role, y | 3 (1–37) |

| Prior research experience | 1 (9%) |

Note: N = 59. Values are given as number (percentage) or median (range). Denominators represent n from each participant type and all data were self-reported.

Abbreviation: GED, general equivalency diploma.

Figure 1.

Study participant selection. Participation rate by stakeholder type is displayed in square brackets. aOf the 7 individuals who expressed interest but were not scheduled for focus groups, 3 individuals (nurses/patient care technicians [PCTs]) indicated participation interest on a sign-up form, but did not respond to follow-up from the research team, and 4 individuals (patients/care partners) indicated initial interest but chose not to participate for unknown reasons. bOf the 15 individuals who met eligibility criteria and were scheduled for focus groups but did not attend, 8 individuals (2 social workers/dietitians and 6 nurses/PCTs) had work conflicts, 4 individuals (1 nurse/PCT and 3 patients/caregivers) did not attend for unknown reasons, 1 individual (nurse/PCT) was sick, 1 individual (nurse/PCT) had a personal conflict (doctor’s appointment), and 1 individual (patient/care partner) had no transportation.

We identified 11 themes that captured barriers to and facilitators of research participation by patients and research facilitation by clinic staff and medical providers in dialysis clinics. We collapsed these themes into 4 categories to create an organizational framework for considering stakeholder, relationship, research design, and dialysis clinic aspects that may affect stakeholder interest in participating in or facilitating research. These themes appear to shape the degree of research-readiness of a dialysis clinic environment. Table 3 displays representative stakeholder quotations. Figure 2 provides a theoretical model for enhancing dialysis clinic research readiness through: (1) increased research knowledge and interest (transitioning from ambivalence to certainty), and (2) alignment of clinical and research activities (transitioning from separation to alignment).

Table 3.

Illustrative Stakeholder Quotations of identified Themes Grouped by Organizational Categories

| Theme | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Individual Stakeholder Related | |

| Narrow research understanding by patients and clinic personnel | “[I think of] drug studies.” (clinic manager) |

| “Medical research is doing lab testing and physical tests.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| “I think about [research] in relation to drugs.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Competing personal priorities among patients | “Lots of [patients] have diabetes, hypertension, and there’s so many other things…” (clinic manager) |

| “As long as it didn’t impose on them. I think that’s the big thing with dialysis patients. They already feel like they’ve been imposed upon—that their lives are no longer theirs.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “There may be time restraints because patients are coming in to treatment three times a week, and they often have medical appointments on the other days.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| “They have financial issues. They have trouble getting their medications. Their insurance is lapsing.” (medical provider) | |

| “Transportation is a huge issue. Most of our patients don’t drive to the unit. They have family members that are picking them up and taking time out of their work schedule, or they ride buses that come at a certain time. You can’t just tell the driver ‘hey, he’s going to be fifteen more minutes’ because they will leave the patient.” (medical provider) | |

| Low literacy and education levels of patients and inadequate research expertise of clinic personnel | “[Providing better explanations] would lessen our frustration with research.” (nurse manager) |

| “Depending on the subject of the research or how it’s conducted, literacy is an issue for a lot of patients.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| “Health literacy is an issue. A lot of these patients don’t really have an awareness of what’s going on in their body and that’s why they’re on dialysis because of their lack of understanding or interest in their health.” (medical provider) | |

| “As far as language, it’s not just English and Spanish. It’s level of English, a post-graduate education in English versus various lower levels of English education.” (medical provider) | |

| “Don’t use those big words… break it down to a human level. Come down to a level that I understand.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Relationship Related | |

| Necessity of trust between clinic personnel and patients and between the research team and clinic stakeholders | “I think in some ways it would be positive because if we (PCTs) present things to [patients], they’ll be more apt to do it because they trust us. I think they listen to us and talk to us more than the doctors.” (nurse/PCT) |

| “I think you’ll get more honest answers because patients tell us (PCTs) more than they tell the social worker or the dietician. So what makes you think they’re going to tell a perfect stranger more? I think that if you want to get more of the truth, then it needs to be a familiar face.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “You would need an ‘in’… somebody that [the staff] trusts.” (medical provider) “Are you doing [research] for yourself or are you doing it for humanity?” (patient/care partner) | |

| “She [clinic nurse] transferred my trust in her to you [researcher], so I never had to worry about anything you said. I completely trusted you because she said, ‘you can trust her.’ And, so, if the doctor, because I trust her skillset the most, said I have a study for you to look into, then the doctor could get out of the way and someone in your position [researcher] could come in. My trust in the doctor is transferred to you, so I don’t have to worry about non-trust building up in my head because the doctor transferred her power to you.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Research buy-in by all stakeholders | “You have to engage patients. You have to be present right there with them from beginning to end...because they’re not going to do it on their own. But if you’re there, they will.” (nurse/PCT) |

| “You have to have the participants buy into the thing that you’re researching. They have to feel some kind of ownership of the outcome. And, it’s not always the same thing that’s going to get everybody interested. You may think that this particular patient doesn’t participate in anything, but if there’s something that means something to them, then you’ve got them.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “Do I want to go out of my way to help [the researchers]? Have they made a connection with me, so that I want to help them?” (patient/care partner) | |

| Altruistic motivations of all stakeholders | “It’s not about money. It’s about knowing they did something to benefit patients in the long run.” (clinic manager) |

| “It goes back to the good of it. Who could it help? How can it help? We want to make things better.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “All it really boils down to is… is this something we believe in? Is it something that’s relevant to what we’re doing, is it something that’s really going to help the patient, is it something that we can really get excited about?” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “We want to be involved in something bigger. We know what we do here, and we have some sense of how we impact patients’ lives, but to be a part of something that’s bigger, that touches more lives, and whether we get to see it or not, it’s still a good thing. It is.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “I’d be more motivated to participate in research if I knew how it was going to help.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| “I would be willing to participate to help anybody in the future that would have the same thing that I had.” (patient/care partner) | |

| “Your research may not help me, but it may help somebody down the line.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Research Design and Operations Related | |

| Research convenience for all stakeholders | “Organization is huge. Don’t tell me that I’m going to have to go on five-hour-long conference calls every day this week, because I don’t have time for that. Organize it, make it efficient.” (clinic manager) |

| “Hopefully nothing other than patients’ presence will be required. Because if you require more than them doing what they already do, which is showing up, then chances are they’re just going to opt out.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “There’s a lot of timing issues that come into play, so someone might walk in the door saying I’m going to be with this patient at this time, this patient at this time, but all that has to be flexible because you may not be able to be near a patient because someone next to them is coming on or off.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| “I mean, it’s a no-brainer, you would try to do [research] while we’re in the center.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Timely follow-up for all stakeholders | “Communicating back to us is where there needs to be improvement. What did they actually do with the data? Did it go into an article? Did it make a change somewhere? What happened with that? That would satisfy us a lot of times.” (clinic manager) |

| “I know you don’t always get to see or to know what the end product of research is. Will we see it in a year, two years, five years, or is this something that’s really long-range and that nothing may come of in say 10 years? We would be more interested if we could see an end product.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “If I knew that the information was going to get back to the patient; if I knew that the patient’s efforts and time were valued enough that they would get follow-up, not just that it would be published but that they would have some kind of validation that what they did contributed to an overall greater purpose.” (social worker/dietitian) | |

| Incentives as participation motivators for patients | “I don’t think like Amazon or iTunes for gift cards [for patients]. They should be from a grocery store, like Walmart. I wouldn’t even say gas [cards] because a lot of patients don’t drive.” (clinic manager) |

| “It’s usually compensation. That’s always the motivator.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “A bingo game. We’ve had the most participation with bingo.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “Money is a great vehicle.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Dialysis Clinic Related | |

| Competing professional demands among clinic personnel and medical providers |

“We already have a million and one things to do and adding this whole extra world of research and all these different things that we have to submit, different reports, different whatever. I think we might have some hesitation with some of our staff, because [research] does create more work. And when people already feel overwhelmed, it can be very difficult.” (clinic manager) |

| “Our jobs and days are long enough as it is. There’s a lot going on during the day. Staying on top of [research] would be too much. But I would want to. If I could, I would do it.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “But on the floor in-center, they’re rush-rush-rush, go-go-go, get the patient in, get the patient out.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “There are sixteen patients in the chair that are coming off in an hour, and you have to bill for them. That’s what the problem comes down to. If you don’t bill, you don’t get paid. It affects everything. If we could remove billing tasks, then probably, yes, I would love to help [with research].” (medical provider) | |

| “Don’t put [research] on the care techs, because they are all overloaded. They have so much to do. They’re running around, and I think I would feel less confident that the research would be done properly. It would just be one more thing on their list they got to do.” (patient/care partner) | |

| Importance of teamwork and communication for all stakeholders | “It’s going to take the whole team. [Research] should be presented by all of the staff—nurses, the dietician, social worker. Everybody should participate. When it comes down to reinforcing, that’s going to be your PCTs. If each PCT can talk to each patient to follow up after we do the education or the roll-out, that’s going to be really helpful.” (clinic manager) |

| “Full disclosure is very important. Make sure that [patients] know that you’re going to tell them what we’re going to do. We’re going to educate you (patients) every step of the way, and we’re not going to do anything without your permission.” (clinic manager) | |

| “[For research to be successful], we need something that gets us all working together on an idea.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “It would help if we were partners. So, instead of the entity who’s doing the research working to solve the problem, now everybody that’s ever participated is helping with it as well.” (nurse/PCT) | |

| “Communication is the biggest word in dialysis. That’s with the research assistants. That’s with your techs. That’s with your doctors. That’s with your nurses. Communicate. Get on the person’s education level. Just communicate.” (patient/ care partner) | |

Note: Quotations are from focus group participants. Stakeholder focus group attribution is listed in parentheses after each quotation.

Abbreviation: PCT, patient care technician.

Figure 2.

Thematic schema.

Themes Reflecting Barriers to and Facilitators of Research Participation and Facilitation

Individual Stakeholder-Related Barriers and Facilitators

Narrow Research Understanding by Patients and Clinic Personnel.

Almost all participants demonstrated some understanding of the purpose of research, but many were unaware of the broad range of research types. One medical provider described research as being about “answering a set of questions and how to improve things.” However, many patients and clinic personnel described research only as clinical trials, specifically “drug studies” or “lab tests.” In general, participants thought that under-standing more about the range of research types would enhance interest in participating in or facilitating research.

Competing Personal Priorities Among Patients.

Participants in diverse roles identified high comorbid condition burdens and limited personal resources as impediments to patient research participation. Financial stressors and transportation constraints were frequently cited as patient barriers. Many participants noted that research must not impose on patients’ lives, recognizing the substantial burden of dialysis therapy itself.

Low Literacy and Education Levels of Patients and Inadequate Research Expertise of Clinic Personnel.

Many participants identified low health literacy and limited formal education among patients as participation barriers. Some participants recognized inadequate research expertise as a barrier to research facilitation by clinic personnel. Several nurses and PCTs recalled being asked to help with studies that were not adequately explained.

Relationship-Related Barriers and Facilitators

Necessity of Trust Between Clinic Personnel and Patients and Between the Research Team and Clinic Stakeholders.

Participants in diverse roles recognized the essential role of trust in generating interest in research participation and facilitation among patients and clinic personnel. For example, several patients expressed that their interest in research participation was tempered by concerns about researchers’ ulterior motives, such as self-advancement or monetary gains. Nurses and PCTs suggested that patients might be more receptive to research participation if studies were first introduced by clinic personnel due to familiarity and trust. Consistent with this expectation, patients viewed research support by clinic personnel as essential to establishing trust with the research team. However, patients reported a preference for learning about research participation specifics from medical providers or study personnel, citing their expertise. One patient described a “transfer of trust” that occurred between clinic and research personnel during recruitment for the present study, saying, “She (clinic nurse) transferred my trust in her to you (researcher), so I never had to worry about anything you said.” Overall, diverse stakeholders recognized the importance of an underlying clinic culture of trust to enhancing patient and clinic personnel openness to research participation and facilitation.

Research Buy-in by All Stakeholders.

Participants recognized the importance of patient and clinic staff buy-in to the concept of research in general and to the specifics of individual studies. One nurse said, “You have to sell it twice. You have to sell it to us (nurses), and sell it to them (patients). Sell it to us, so we can sell it to them and get them interested.” Clinic personnel noted the importance of introducing study concepts and goals to clinic stakeholders early in the research process to spark interest.

Altruistic Motivations of All Stakeholders.

Many participants described the importance of understanding the research’s potential benefits for patients to gaining stake-holder buy-in and decreasing ambivalence toward research participation and facilitation. Altruism was a common motivator for both patient and clinic personnel interest in research participation and facilitation. One nurse said, “People have to buy into the good—the greater good—of where you’re trying to go.” Several nurse managers described research communication received in the past as being too role-specific. They reported that communication of the “bigger picture” would increase their interest in facilitating research.

Research Design and Operations-Related Barriers and Facilitators

Research Convenience for All Stakeholders.

Participants in diverse roles repeatedly emphasized time and clinical duty pressures as barriers to research participation and facilitation. They also cited the rigidity of treatment and transportation schedules as barriers to participation and facilitation. Suggestions for overcoming these challenges included performing research activities at the dialysis clinic and incorporating data collection and study visits into routine clinical visits. Home therapies nurses and patients generally thought that research facilitation by clinic nurses was more feasible in home dialysis programs, in which clinic visits offer more face-to-face time. Time pressures drove clinic personnel’s desire for succinct research education.

Timely Follow-up for All Stakeholders.

Patients and clinic personnel underscored the importance of providing follow-up about study progress and findings to research participants and facilitators. One patient said, “It would be really nice, and if we knew it up front, that you would eventually share the results. It’d be really motivating for people to know what happened.” Better follow-up was recognized as a way to improve participant retention and protocol adherence, as well as increase interest in future studies. Several nurse managers cited poor follow-up in studies they had helped facilitate as deterrents to their interest in facilitating future studies. Most participants recognized research as a long process but requested up-dates about progress at prespecified communicated intervals.

Incentives as Participation Motivators for Patients.

Many participants discussed the role of tangible incentives in research promotion. However, in general, money and other incentives were viewed as less important than the belief that the research had the potential to improve the lives of future patients. Some participants thought that tangible incentives such as money and prizes might in-crease patient research participation interest.

Dialysis Clinic−Related Barriers and Facilitators

Competing Professional Demands Among Clinic Personnel and Medical Providers.

Clinic personnel, medical providers, and patient participants identified primary job responsibilities as the greatest barriers to research facilitation by clinic personnel and medical providers. Participants worried that competing time demands could compromise both research and clinical care integrity. One physician said that researchers could not rely on medical providers for study facilitation due to time constraints, commenting, “You have to see [patients] when they’re on dialysis. You’re racing against time, and you’re racing between units.”

One patient expressed concerns about PCT involvement in research facilitation, saying, “It would be okay for the tech to help with [research], but the company should provide funding for them and the time off to do it. You can’t expect them to do that while they’re working.” To address these concerns, several nurses and PCTs suggested use of clinical “floaters” to off-set workloads. Opportunities to facilitate research on non–work days was appealing to some.

Importance of Teamwork and Communication for All Stakeholders.

Almost all participants described research as a “team” activity. Citing trust and shared goals, participants viewed all clinic personnel and medical providers as key research facilitators. Several participants suggested that clinic personnel might best foster research readiness through research awareness and outward displays of research initiative support. One nurse said, “It would help if we were [research] partners.” Participants also noted the importance of regular communication from the investigative team to sustain interest. Table 4 summarizes stakeholder-suggested strategies for increasing research participation and facilitation interest.

Table 4.

Stakeholder-Suggested Strategies for Stimulating Interest in Research Participation by Patients and Research Facilitation by Dialysis Clinic Personnel and Medical Providers

| Suggestions | Stakeholder Groupa |

|---|---|

| Highlight potential research benefit to future patients | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Obtain stakeholder buy-in | 1, 2, 5 |

| Build trust between clinic stakeholders and research team | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Use trusted research messenger | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Perform in-person recruitment | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Provide research follow-up | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Improve clinic teamwork and engagement | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Increase clinic stakeholder general research knowledge | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Improve communication of research purpose and plans | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Add clinical operations support | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Provide research participant incentives | 1, 2, 5 |

Stakeholder group type making the suggestion: 1 = clinic manager, 2 = nurse/ patient care technician, 3 = social worker/dietitian, 4 = provider, and 5 = patient/ care partner.

Research Education and Communication Preferences

Box 1 displays participant-suggested strategies for general research education and study-specific recruitment and training materials. Participants overwhelmingly preferred short communications delivered in multiple formats to appeal to different learning styles. Most preferred in-person communication on research education and study participation/facilitation opportunities followed by rein-forcing written materials. Clinic personnel participants suggested that patients were generally averse to written materials. However, patients expressed desire for written materials as follow-up to video or in-person formats, referencing interest in reviewing materials outside the clinic. Diverse stakeholders suggested providing material in video format.

BOX. 1. Stakeholder-Suggested Strategies for Research Education, Study Recruitment, and Training Materials.

Provide materials in multiple formats (written, verbal, video, and online)

Adapt language and content to suit intended audience’s education and literacy levels

Use color and animation to promote visual appeal and hold audience attention

Provide in-person follow-up to written materials for reinforcement and understanding checking

Keep materials succinct

Use white space, bullets, and pictures to break up text blocks

Infuse materials with hope via use of a positive tone

Note: Supportive quotations are listed in Table S3.

Discussion

Few studies, if any, have evaluated local dialysis clinic stakeholder perceptions of research participation by patients and research facilitation by clinic personnel and medical providers. Our exploratory study findings revealed stakeholder interest in participating in and facilitating research, particularly research that has the potential to improve the lives of future patients. However, we identified numerous individual, relationship, research operations, and clinic barriers to stakeholder engagement in research, including knowledge gaps, mistrust, competing personal and professional priorities, and disjoined clinical and research activities, among others. Encouragingly, our results suggest that creation of a research-ready dialysis clinic environment is feasible despite these barriers. Two key synergistic processes emerged as central to promotion of a research-ready clinic environment: (1) cultivation of a research-informed and knowledgeable atmosphere via dialysis stakeholder education, and (2) alignment of clinical and research activities to cultivate an atmosphere of teamwork and reduce operational barriers to research participation and facilitation.

This study provides insight into some of the challenges associated with implementing research in dialysis clinics. In recent years across medical disciplines, there has been an increased focus on efficiency and generalizability of comparative effectiveness research.12,13 Pragmatic, also referred to as “real-world,” clinical trials are one example of such research. With the goal of yielding highly clinically applicable results, pragmatic trials incorporate implementation of the intervention and data acquisition into the delivery of clinical care.13,14 Pragmatic trials are of substantial interest to the dialysis community.15 An expert work group recently catalogued challenges in dialysis pragmatic trial implementation.15 In addition to ethical and regulatory issues, cultural challenges, such as varied levels of research understanding and interest among dialysis clinic stakeholders, and operational challenges, such as absence of systems to engage local stakeholders, were identified as areas of needed focus.15

Our findings may offer preliminary guidance in tackling these challenges. While focus group participants displayed ranging degrees of sophistication with respect to research understanding, almost all viewed research positively. Altruistic tendencies tended to outweigh concerns about potential research ulterior motives, such as researcher financial gains. Participants expressed a desire to under-stand the bigger picture of research initiatives to contextualize their potential impact with their own experiences. These observations are consistent with empirical evidence demonstrating that the establishment of personal research context for stakeholders is important for successful research implementation.16 Clearly defining short- and long-term potential research consequences and providing follow-up about study progress to stakeholders were seen as essential to cultivating and sustaining interest in research participation and facilitation and building trust in the research process in general.

Stakeholders also acknowledged the importance of trusting relationships to patient research participation and clinic personnel research facilitation. For some, trust in the research messenger was established on the basis of familiarity, as with clinic personnel. For others, trust in the research messenger was based on perceived expertise, as with medical providers. Past experiences also affected trust. Several clinic personnel attributed their mistrust in re-searchers to prior experiences in which they dedicated effort to research initiatives and received little follow-up about initiative progress. Such findings are consistent with the well-described association between clinical trial enrollment and trust in health care systems and medical providers, particularly among minority populations.17–19 Moreover, trust is known to moderate information receptivity.20 Individuals process information differently when delivered by trusted versus untrusted individuals,20 thereby highlighting the importance of the messenger in patient recruitment and staff engagement. One patient explicitly described a “transfer of trust” that occurred upon introduction to our research team by a trusted dialysis nurse. Finally, our findings underscore the importance of an established clinic culture of trust among patients, personnel, and medical providers to overall clinic research readiness.

Our results also suggest that alignment of clinical and research activities may help foster a research-ready environment. Diverse stakeholders were skeptical that clinic personnel could perform research activities while engaged in clinical care duties. Integration of research and clinical care may be feasible in clinics with embedded research infrastructures and/or dedicated research coordinators, but such settings are uncommon and costly. However, some degree of clinical and research alignment may be possible without having to rely on clinic staff for performance of essential research tasks. Participants routinely cited the importance of an atmosphere of teamwork in which all stakeholders are equipped with general research and study-specific knowledge, positioning them to champion research processes and build trust between patients and researchers. A picture of a research-ready clinic environment emerged whereby local dialysis stakeholders cultivated a supportive and team-oriented research atmosphere driven by the common goal of improving the lives of patients through incremental research discoveries. Notably, clinic personnel would in most cases not directly perform key research tasks such as recruitment and data collection, but instead would indirectly support research processes by raising research awareness and enabling research team members.

To effectively contribute to a research-ready atmosphere, all clinic stakeholders require basic levels of general research and study-specific knowledge. Participants voiced a preference for research education and communication delivered in short accessible formats. Both an uplifting tone and attention to literacy and education levels of patients and clinic personnel were identified as essential. Overall, participants thought that succinct, positive, and education-level appropriate research communications would promote understanding and interest in research participation and facilitation across stakeholders. This finding highlights the importance of providing adequate training in the general principles of research, as well as study-specific information to all clinic stakeholders before research implementation.

The primary limitations of our study relate to its transferability to other practice settings and potential biases. Participants were from clinics staffed by a single large dialysis organization, and 6 of the clinics are university affiliated. However, despite academic affiliation, less than a quarter of participants had prior research experience. Blacks were over-represented, reflective of the local dialysis population. However, well-established research misperceptions and mistrust among minority populations render oversampling of this population important. It is plausible that individuals from different backgrounds may have other perspectives, as well as those from clinics operated by different dialysis providers or associated with different universities. This was an exploratory study that sought to characterize general perspectives across diverse stakeholders. Given the stakeholder diversity, we did not attempt to draw conclusions about specific stakeholder types and thus could not fully assess thematic saturation. We ended the study after no new themes emerged from the last 2 focus groups, but other perspectives may exist. Additional research within individual stakeholder groups and with stakeholders from more diverse clinics is needed. Finally, we did not specify research type (observational study, qualitative study, or clinical trial). However, most participants equated research with “clinical trials,” so the results are likely most applicable to interventional studies. Perspectives may differ by research type, and exploration of such potential differences is material for future studies.

In conclusion, the perspectives shared by our participants suggest that despite competing personal and professional demands and generally narrow research understanding, there is substantial appetite for research participation and facilitation among dialysis clinic stake-holders. Driven by altruism, our participants voiced interest in increased research engagement but acknowledged the need for additional support in the forms of accessible education and alignment of clinical and research activities. Findings offer encouragement and direction as we seek to build research-ready dialysis clinic atmospheres.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: COREQ 32-item checklist*

Table S2: Focus group moderator guide topics and representative questions.

Table S3: Illustrative quotations of stakeholder perspectives on research education and study recruitment and training materials.

Acknowledgements:

We dedicate this article to the memory of Celeste Castillo Lee, a tireless advocate for individuals receiving dialysis and their care partners. She contributed to the development and early execution of this project. Her spirit along with her vision for meaningful stakeholder engagement remain guiding forces for the investigative team. We thank the patients and employees at the participating Carolina Dialysis and Fresenius Kidney Care dialysis clinics for their time and engagement and the members of our stakeholder panel for their time and expertise: Cynthia Christiano, Jessica Farrell, Richard Fissel, Barbara Gillespie, Jay Ginsberg, Colleen Jabaut, Jenny Kitsen, Brigitte Schiller, Terry Sullivan, and Amy Young.

Support: This project was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Eugene Washington PCORI Engagement Award (EA-3253) to Dr Flythe. Dr Flythe is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K23 DK109401. Dr Dember is supported by NIH grants UH3DK102384 and U01DK099919. Frenova Renal Research also supported this study. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Dr Flythe has received speaking honoraria from American Renal Associates, the American Society of Nephrology, the National Kidney Foundation, Baxter, and multiple universities and has received research funding for studies unrelated to this project from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Kidney Care, North America. Ms Ordish is an employee of Fresenius Kidney Care. Fresenius had no role in the design or implementation of this study or in the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:The other authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Peer Review: Received July 17, 2017. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers and a methods reviewer, with editorial input from an Acting Editor-in-Chief (Editorial Board Member Francis L. Weng, MD, MSCE). Accepted in revised form October 3, 2017. The involvement of an Acting Editor-in-Chief to handle the peer-review and decision-making processes was to comply with AJKD’s procedures for potential conflicts of interest for editors, described in the Information for Authors & Journal Policies.

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. Flythe, University of North Carolina (UNC) Kidney Center, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Julia H. Narendra, University of North Carolina (UNC) Kidney Center, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Adeline Dorough, University of North Carolina (UNC) Kidney Center, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, Departments of Health Behavior, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Jonathan Oberlander, Health Policy and Management and Social Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Antoinette Ordish, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; Vancouver, WA, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Caroline Wilkie, Punta Gorda, FL, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

Laura M. Dember, Renal-Electrolyte and Hypertension Division, Department of Medicine and Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA..

References

- 1.Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Schena FP. The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15(2):411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inrig JK, Califf RM, Tasneem A, et al. The landscape of clinical trials in nephrology: a systematic review of Clinicaltrials.gov. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63(5):771–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey JR, Hanson CS, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Patients’ perspectives on hemodialysis vascular access: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64(6):937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Establishing core outcome domains in hemodialysis: report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Consensus Workshop. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;69(1):97–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of Community Engagement Vol 2017 2nd ed. National Institutes of Health; 2011. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for in-terviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners London, UK: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuest J Negotiating with helping systems: an example of grounded theory evolving through emergent fit. Qual Health Res 2000;10(1):51–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser B Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Califf RM, Sanderson I, Miranda ML. The future of cardiovascular clinical research: informatics, clinical investigators, and community engagement. JAMA 2012;308(17):1747–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford I, Norrie J. Pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med 2016;375(5): 454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 2003;290(12):1624–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dember LM, Archdeacon P, Krishnan M, et al. Pragmatic trials in maintenance dialysis: perspectives from the Kidney Health Initiative. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27(10):2955–2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J. Intervention description is not enough: evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in rando-mised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials 2012;13:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep 2003;118(4):358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YY, Lin JL. Trust but verify: the interactive effects of trust and autonomy preferences on health outcomes. Health Care Anal 2009;17(3):244–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillen MA, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician-a review. Psychooncology 2011;20(3):227–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurd TC, Kaplan CD, Cook ED, et al. Building trust and diversity in patient-centered oncology clinical trials: an integrated model. Clin Trials 2017;14(2):170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Dialysis Facility Compare https://data.medicare.gov/data/dialysis-facility-compare. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- 22.US Census Bureau. 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Accessed September 6, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: COREQ 32-item checklist*

Table S2: Focus group moderator guide topics and representative questions.

Table S3: Illustrative quotations of stakeholder perspectives on research education and study recruitment and training materials.