Abstract

Naturally occurring carotenoids have been isolated and used as colorants, antioxidants, nutrients, etc. in many fields. There is an ever-growing demand for carotenoids production. To comfort this, microbial production of carotenoids is an attractive alternative to current extraction from natural sources. This review summarizes the biosynthetic pathway of carotenoids and progresses in metabolic engineering of various microorganisms for carotenoid production. The advances in synthetic pathway and systems biology lead to many versatile engineering tools available to manipulate microorganisms. In this context, challenges and possible directions are also discussed to provide an insight of microbial engineering for improved production of carotenoids in the future.

Keywords: Carotenoids, Synthetic biology, Systems biology, Membrane engineering

Introduction

Carotenoids are naturally occurring products initially recognized as colorants owing to absorption of blue light and appearance of yellow to red colors. To date, plenty of these compounds (> 1100) have been found from many species of bacteria, eukaryotes, and some archaea [1]. They are built up from five-carbon (C5) isoprene units and rearranged to form long-chain carotenes or xanthophyll, which contain several conjugated double bonds. Besides as colorants, this characteristic chemical structure features their physiological functions as antioxidants, provitamin A nutrients, and UV protection agents. A medical potential has been also observed in prevention of chronic diseases and tumors [2]. With the roles in redox homeostasis and human health [3], they are widely used in industry as food ingredients, cosmetic bioactive substances, and medicinal compounds. C40 carotenoids are the major ones (> 95%), where lycopene, β-carotene zeaxanthin, lutein, β-cryptoxanthin are well known carotenoids in human diets [4]. Global market for carotenoids has reached $1.5 billion in 2017 and is expected to grow to $2.0 billion by 2022 [5]. There is limited production of carotenoids from natural resources [6]. Thus, microbial production of carotenoids is a prospective alternative way to meet an ever-growing demands [7, 8] because microbial production is easily scalable with increase of fermentation capacity and not affected by variations of season, climate, regions, etc. Moreover, microbial synthesis affords more bioactive products than chemical synthesis owing to region- and stereo-selective enzymes. In this review, we summarize current advances and the challenges in microbial engineering for carotenoid production.

Biosynthetic pathways of carotenoids

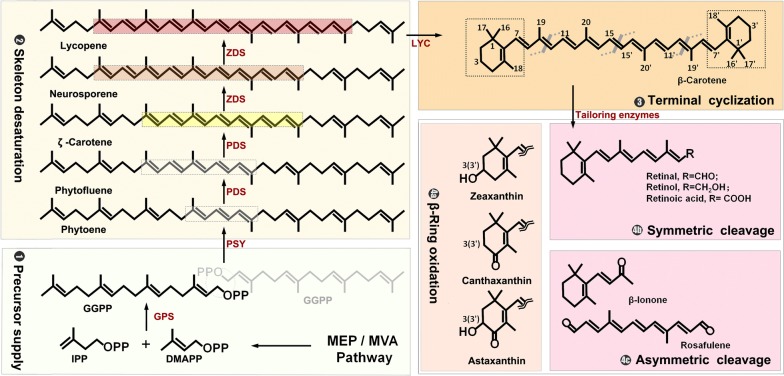

Biosynthesis of carotenoids can be divided into four steps: geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20) precursor supply, phytoene desaturation, lycopene cyclization, and carotene modifications (Fig. 1). Mevalonate (MVA) pathway in eukaryotes and some bacteria, and the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in most bacteria and plant plastids are engaged in synthesis of isoprene units, dimethylally diphohsphate (DMAPP, C5) and isopentenyl diphosphates (IPP, C5). One DMAPP and three IPPs are condensed into one GGPP in a series of prenyltransferase reactions. Variation of the prenyltransferases of the condensation reactions can alternate the precursor to farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15) and geranylfarnesyl diphosphate (GFPP, C25), which serve as the precursors of minor C30 and C50 carotenoids. A linear colorless phytoene is initially generated from head-to-head condensation of two GGPPs by phytoene synthase (PSY), which serves as a gatekeeper of C40 carotenoid synthesis [9]. In general, phytoene undergoes a four-step desaturation by phytoene desaturase (PDS) and ξ-carotene desaturase (ZDS), and two complementary isomerizations by 15-cis-ζ-carotene isomerase (ZISO) and carotenoid isomerase (CRTISO), which results in the formation of a red-colored lycopene with the fully conjugated undecane chromophore [10]. In contrast, bacterial carotene desaturase, called CrtI, solely takes over these four-step desaturations [11]. The stepwise desaturation lead to intermediates with c.d.b. number from 3 to 11, which renders different colors when the c.d.b. number exceeds seven [12]. Different lycopene cyclases then catalyze to introduce β- or ε-ring at chain ends of lycopene to form α-, β-, γ- or δ-carotene according to a double bond position of the ionone ring [13, 14]. These carotene products present diversity in geometrical skeleton of carotenoids, which can be hydroxylated at the terminal ionone ring by hydroxylase and ketolases to form various xanthophylls. For example, the addition of hydroxyl groups to C-3(3′) position of β-carotene yields zeaxanthin, while 4(4′)-ketolation of β-carotene results in canthaxanthin product. The oxidative C-3(3′) and/or C-4(4′) positions of β-carotene can happen in many combinatorial orders to generate intermediates of astaxanthin [15]. There are also further modifications of carotenoids such as glycosylation (e.g., myxol 2′-fucoside) and acetylation (e.g., dinoxanthin) not discussed herein. These carotenoids can be oxidatively cleaved to generate apocarotenoids, including retinoids and non-retinoids by carotenoid cleavage oxygenase/dioxygenases or 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs) [16]. The most renowned retinal is derived from symmetric cleavage of β-carotene at central (15,15′-) double bond, while asymmetric cleavages at 9,10- and/or 9′,10′- double bonds generate β-ionone, and β-apo-10′-carotenal or rosafluene. It could give a great interest to mine more pathways for production of apocarotenoids from parent carotenoids such as β-carotene and lycopene.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of carotenoids biosynthesis. Carotenoids synthesis can be divided into four stages: precursor supply, skeleton desaturation, terminal cyclization, and product tailoring. The conjugated double bands (c.d.b.) formed in desaturation stage are boxed with different color. The numbering of C40 carotenoids is exemplified by using β-carotene. The symmetric oxidations of β-ring generate zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, and astaxanthin. The cleavage positions are presented on β-carotene, which leads to the symmetric products of retinoids and the asymmetric product of ionones. GPS GGPP synthase, PSY phytoene synthase, PDS phytoene desaturase, ZDS ζ-carotene desaturase, LYC lycopene cyclase

Microbial production of carotenoids using a native producer

Microbial production of carotenoids is a promising way for economic and mass production of natural-origin carotenoids (Table 1). Fermentation of heterothallic Blakeslea trispora and Phycomyces blakesleeanus, native carotenogenic (crt) fungi, is known as a representative way of microbial production of carotenoids in an industrial scale [17]. The culture has been optimized in culture media and various fermentation parameters [18]. Manipulation of oxygen transfer rate (OTR) at 20.5 mM/L/h leads to β-carotene production of 704.1 mg/L, because reactive oxygen species (ROS) are formed in the high OTR condition and stimulates carotenoid synthesis [19]. A waste cooking oil is used as a cheap carbon source to produce more than 2 g/L of carotenes [20]. Lycopene production from B. trispora is achieved by addition of lycopene cyclase inhibitors such as 2-methyl imidazole, where 256 mg/L of lycopene was produced by using a bubble column reactor [21]. Microbial carotenoids production using a native producer are thus focused on isolation of robust strains able to use low-cost substrates and development of competitive bioprocess [22].

Table 1.

Representative engineering strategies for carotenoid production from microbial hosts

| Host strains | Descriptions | Products and titers | Engineering strategies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blakeslea trispora | Native producer of carotenoids, | β-Carotene 704.1 mg/L | Control of oxygen transfer rate | [19] |

| Lycopene, 256 mg/L | Optimization of fermentation with lycopene cyclase inhibitor | [21] | ||

| Escherichia coli | Genetically tractable, non-native producer | Lycopene, 0.5 g/g DCW | Regulation of lycopene synthesis pathway expression | [28] |

| β-Carotene, 2.1 g/L | Engineering MEP pathway for IPP and DMAPP supply and central pathway (TCA, PPP) for carbon flux | [31] | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Genetically tractable, non-native producer | Lycopene, 56 mg/g DCW | Increase of acetyl-CoA pool and optimization of lycopene synthesis pathway via genome manipulation | [34] |

| Astaxanthin, 218 mg/L | Genome evolution by ARTP | [36] | ||

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Native producer of C50 carotenoid | β-Carotene, 7 mg/L | Deletion of crtR and integration of crt pathway genes | [40] |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | Phototroph with carotenogenic genes | Lycopene, 10 mg/g DCW | Replacement of crtI, augmentation of MEP pathway, and block of PPP pathway | [43] |

| Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous | Astaxanthin producer | Zeaxanthin, 0.5 mg/g DCW | Mutagenesis of astaxanthin synthase and overexpression of β-carotene hydrolase | [47] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Genetically tractable, non-native producer | β-Carotene, 6.5 g/L | Optimization of promoter-gene pairs of heterologous crt pathway | [53] |

| β-Carotene, 4 g/L | Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes | [52] |

Metabolic engineering of microbes for carotenoid production

With advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, many efforts have been conducted to produce carotenoids from genetically tractable microorganisms (e.g., Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae), which is well reviewed elsewhere [23, 24]. Biosynthesis pathway of lycopene or β-carotene has been often introduced and engineered in non-carotenogenic hosts owing to available genetic collections of the pathways. Engineering strategies include enhancement of IPP and DMAPP precursors supply by overexpression of rate-limiting enzyme of the MEP or MVA pathway, optimization of heterologous crt pathway, and modification of host chassis. Balanced augmentation of IspG and IspH in MEP pathway could eliminate accumulation of the pathway intermediates, and improve lycopene and β-carotene production [25]. MVA pathway possesses great potential for isoprenoids production [26], and heterologous expression of MVA pathway increases β-carotene production to 465 mg/L in an engineered E. coli [27]. Thanks to colorimetric traits of carotenoids, synthetic pathways of carotenoids are often adopted for validation of designing concepts in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Thus, it provides many novel strategies to optimize crt pathways [28, 29]. A new combinatorial multigene pathway assembly scheme is implemented with use of well-characterized genetic parts of lycopene synthesis, resulting in lycopene production of 448 mg/g DCW [28]. E. coli is rationally evolved to accommodate lycopene production by multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) in a short time [30], ATP and NADPH supplies for β-carotene production are improved by engineering central metabolic modules of carbon sources assimilation (EMP and PPP pathways), which allows 2.1 g/L of β-carotene production from the engineered E. coli in a fed-batch culture [31]. As robust carotenoids production depends on a stability of carotenogenic pathway plasmids, engineering of the plasmids stability based on hok/sok system yields a reproducible production of 385 mg/L astaxanthin from recombinant E. coli [32]. To achieve a high-level, genetically stable expression of heterologous genes and pathways, chemically inducible chromosomal evolution (CIChE) is successfully applied to optimize genes dosage of chromosomal-integrated lycopene pathway in E. coli [33]. S. cerevisiae is engineered to produce lycopene through combining host engineering to increase acetyl-CoA pool and pathway engineering to optimize genes expression, resulting in a 22-fold increase in lycopene production (55.6 mg/g DCW) as compared to its initial strain [34]. An increase in availability of NADPH by overexpression of STB5 transcription factor yields 41.8 mg/L of lycopene in S. cerevisiae with the engineering efforts to reduce ergosterol synthesis and to enhance MVA pathway [35]. A combined approach of heterologous carotenoids module engineering and mutagenesis by atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP) could make S. cerevisiae produce 218 mg/L of astaxanthin [36].

Development of microbial hosts for carotenoid production

With expansion of available synthetic biology tools various microorganisms are manipulated to produce carotenoids. Corynebacterium glutamicum, a native producer of C50 decaprenoxanthin, is well known for amino acid production as well as vigorous sugar utilization with less carbon catabolite repression [37]. A deletion of crtR in C. glutamicum results in derepression of crt operon and a several-fold increase in lycopene, β-carotene and decaprenoxanthin production [38]. Carotenoids production is also improved by overexpression of σ-factor (sigA) in C. glutamicum [39]. Simultaneous production of l-lysine, 1.5 g/L and β-carotene, 7 mg/L using xylose as alternative feedstock was obtained from C. glutamicum with a series of integrations of crt pathway and lysine pathway as well as deletion of crtR [40]. Purple bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a facultative anaerobic phototroph with a set of crt genes for synthesis of spheroidene and spheroidenone [41]. Rb. sphaeroides has highly-invaginated membrane structure which would favor carotenoid deposition [42]. It was engineered to produce 10.32 mg/g DCW of lycopene by replacement of endogenous neurosporene hydroxylase (CrtC) with heterologous phytoene desaturase (CrtI) along with augmentation of MEP pathway and block of carbon flux to pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [43]. Diploid Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous is capable of astaxanthin synthesis. Overexpression of rate-limiting GGPP synthase by promoter engineering has improved astaxanthin content by 1.7 folds [44]. Deletions of diploid CYP61 genes encoding sterol desaturase could relieve feedback inhibition of ergosterol to MVA pathway, and promote astaxanthin production by 1.4 folds [45]. A mutagenic treatment generated its variants accumulating β-carotene [46], which was engineered for zeaxanthin production, 0.5 mg/g DCW by introduction of β-carotene hydroxylase [47]. Yarrowia lipolytica, an oleaginous yeast is an industrial organism for cost-effective production of compounds derived from acetyl-CoA [48]. There are many genetic tools developed to engineer Y. lipolytica over decades [49]. It is thus regarded as a promising host for production of carotenoids derived from acetyl-CoA via MVA pathway. A heterologous lycopene pathway was introduced in Y. lipolytica engineered to increase the size of lipid bodies by deletion of peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway, which favored lycopene deposits in the lipid bodies and increased the production [50]. Overexpression of MVA pathway and alleviation of auxotrophy in Y. lipolytica PO1f strain allow 21.1 mg/g DCW of lycopene production [51]. An efficient β-carotene pathway was generated by using strong promoters and multiple gene copies for the synthesis pathway, which brought 4 g/L of β-carotene production under optimized fed-batch culture [52]. A combinatorial approach based on Golden Gate assembly was implemented to optimize promoter-gene pairs of heterologous crt pathway, by which a best strain yielded 90 mg/g DCW of β-carotene with a titer of 6.5 g/L in fed-batch culture [53]. Y. lipolytica thus shows a great potential as a competitive host strain for production of carotenoids.

Challenges and outlook in microbial production of carotenoids

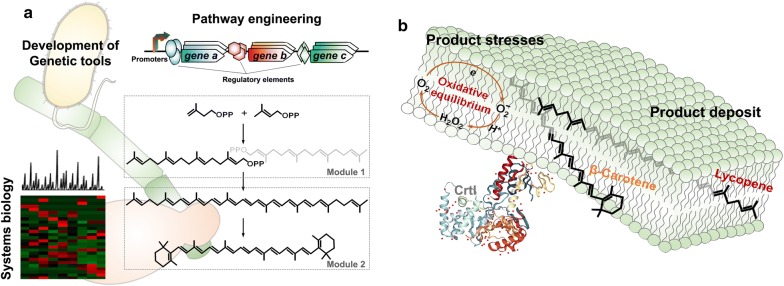

Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology have demonstrated many great successes in microbial production of carotenoids as aforementioned. Engineering efforts for the successes include overexpression of rate-limiting genes, blocking of competing pathways draining precursors, products or cofactors, and removal of endogenous regulatory loops. The engineering strategies are mostly employed for production of lycopene and β-carotene, because their synthesis pathways are well known and characterized to benefit proof-of-principle demonstrations in synthetic biology (Fig. 2a). As there are many industrially interesting carotenoids such as xanthophylls and apocarotenoids, the engineering efforts are required to address production of various carotenoids beyond lycopene and β-carotene, and their derivatives. Retinoids, symmetric cleavage products of β-carotene, are produced to 136 mg/L with introduction of β-carotene 15,15′-monooxygenase (BCMO) in E. coli engineered to produce β-carotene [54]. The retinoids composition can be modulated by overexpression of promiscuous endogenous oxidoreductase YbbO, reducing retinal to retinol [55]. α- and β-Ionone are asymmetric cleavage products of carotenoids. They are produced by employment of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) in an engineered E. coli producing ε- or β-carotene, where ~ 30 mg/L and ~ 500 mg/L of ionones were produced in flask and bioreactor, respectively [56]. Colorless phytoene and phytofluene, carotenoids precursors to lycopene, receive attentions in their nutritional aspects [12, 57]. Phytoene production can be attained by disrupting its desaturation step and yield of 7.5 mg/g DCW is reported in X. dendrorhous [58]. Rare C50 carotenoids have longer c.d.b. and superior antioxidative properties than C40 carotenoids, whose synthesis is observed from few microorganisms in a low titer [9, 59]. Production of C50 carotenoids is addressed by directed evolution of key crt enzymes determining carbon chain backbone lengths in C40 carotenoids synthesis pathway [60, 61]. A new perspective in microbial production of carotenoids could be expansion of catalog of carotenoids from usual carotenes to xanthophylls, apocarotenoids and rare carotenoids.

Fig. 2.

Possible engineering directions for microbial production of carotenoids. Many synthetic biology tools are developed and implemented to pathway engineering in many microbial hosts to increase carotenoid synthesis. Rational manipulation of synthetic pathway will rely heavily on systems biology to understand the cross-talk between carotenoid synthesis pathway and host metabolic network (a). Carotenoids and crt enzymes are associated with membrane. Membrane structural integrity and dynamics are requisite of cell survival, which restricts cellular accumulation of carotenoids (b). Representative structure of CrtI protein (PDB: 4DGK) is visualized by using NGL viewer

Most engineering strategies mainly focus on stoichiometric modulation of pathway components or enhancement of metabolic flux by pushing and pulling, which are also applied successfully to carotenoids production. However, a distinctive engineering strategy is required for carotenoids production beside on the general strategies because some of enzymes in carotenogenic pathways and their substrates are present in membrane regions (Fig. 2b). Lycopene is a desaturated product by lipophilic phytoene desaturases, plastidal PDS/ZDS or bacterial CrtI [10, 11]. Both the plant and bacterial enzymes are translocated to membrane after translation, and CrtI activity depends on a concerted process of flavin-binding and membrane association [62, 63]. Thus, engineering of membrane localization of crt pathway components can favor them to access their hydrophobic substrates and redox partners located in the membrane. β-Carotene ketolase and hydroxylase are engineered to co-localize in membrane through fusion with glycerol channel protein (GlpF), which increases astaxanthin production by 2.2 folds [64]. Carotenoids production would be restricted at a certain extremity level by limited storage space and product toxicity, caused by carotenoids deposition in cytosolic membrane. As carotenoids are deposited in cellular membranes or neutral lipid droplets, a maximized microbial production of carotenoids could be obtained by expansion of cellular membranes or augmentation of neutral lipid droplets formation.

Heterologous carotenoids synthesis pathways have been knocked into chromosomes of host microorganisms by genome engineering tools such as Cas9-CRISPR for stable maintenance of the heterologous pathways with no use of antibiotic selection pressure [65, 66], resulting in a stable production of β-carotene, 2.0 g/L in E. coli [67]. Cas9-CRISPR tool has been developed in many species such as S. cerevisiae and Y. lipolytica [68–70]. Rewiring of host metabolism in a genome level could be attained conveniently with CRISPR tools enabling knock-down or knock-out of chromosomal genes as well [71]. Glycolytic pathway generates acetyl-CoA with a theoretical carbon yield of 66.7% owing to pyruvate decarboxylation. Maximum carbon yield of MVA pathway could not be higher than 55.6% because of carbon loss at decarboxylation of mevalonate diphosphate as well as the loss of the glycolytic pathway. Rerouting carbon flux using PPP can minimize carbon loss and improve yield of isoprenoids [72]. Recent genetic tools including Cas9-CRISPR help metabolic engineers rewire metabolisms of various hosts at ease. Systems biology promises a comprehensive understanding of whole metabolic process with collective measuring of various cellular components such as entities of RNAs, proteins, and metabolites [73]. The multi-level Omics data are often integrated with computational approaches together to discriminate varying production phenotype in a holistic manner [74, 75]. It would be of the most interest to know the stresses from a featured crt pathway and carotenoid products as well as host response to them, which could in turn guide optimization of host engineering.

Overall, carotenoids show many benefits in health, nutrition, and better well-being. Microbial production of carotenoids is the alternative to us to meet the ever-growing demand of these valuable compounds. It is envisaged expansion of microbial carotenoids catalog by mining pathways which have not yet been identified, and manipulation of microbial hosts based on understanding of how cells accommodate carotenoids (Fig. 2). Efforts towards the challenging issues will be an important basis for industrial production of carotenoids. With emerging synthetic biology and systems biology tools, more progresses will be made to develop microbial cell factories for mass production of carotenoids in the future.

Authors’ contributions

CW and SWK developed the ideas and drafted the manuscript. XS, SZ, JBP, SHJ, HJP, and WJK collected the literatures and drew the figures. CW, GW, and SWK professionally edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to thank Prof Cheng liang Gong at Soochow university for his valuable comments on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant (NRF-2016R1A2B2010678) from the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by MSIP, a Grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (SSAC, Grant#: PJ01326501), RDA, Korea, and National Natural Science Foundation of China (21878198). Wang C. was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M610350). Wang C. and Wei G. also thanked a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chonglong Wang, Email: clwang@suda.edu.cn.

Shuli Zhao, Email: zhao.lili@foxmail.com.

Xixi Shao, Email: 15225396909@163.com.

Ji-Bin Park, Email: zbeans90@gmail.com.

Seong-Hee Jeong, Email: jshe89@nate.com.

Hyo-Jin Park, Email: phj4792@naver.com.

Won-Ju Kwak, Email: kj7058wendy@naver.com.

Gongyuan Wei, Email: weigy@suda.edu.cn.

Seon-Won Kim, Email: swkim@gnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Yabuzaki J. Carotenoids Database: structures, chemical fingerprints and distribution among organisms. Database (Oxford) 2017;2017:bax004. doi: 10.1093/database/bax004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggersdorfer M, Wyss A. Carotenoids in human nutrition and health. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;652:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barros MP, Rodrigo MJ, Zacarias L. Dietary carotenoid roles in redox homeostasis and human health. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:5733–5740. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro D, Freitas M, Silva AMS, Carvalho F, Fernandes E. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant activities of carotenoids and their oxidation products. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;120:681–699. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWilliams A: The global market for carotenoids. bccResearch 2018, FOD025F.

- 6.Adadi P, Barakova NV, Krivoshapkina EF. Selected methods of extracting carotenoids, characterization, and health concerns: a review. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:5925–5947. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leavell MD, McPhee DJ, Paddon CJ. Developing fermentative terpenoid production for commercial usage. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;37:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Ding W, Jiang H. Engineering microbial cell factories for the production of plant natural products: from design principles to industrial-scale production. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:125. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0732-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umeno D, Tobias AV, Arnold FH. Diversifying carotenoid biosynthetic pathways by directed evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:51–78. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.51-78.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz-Sola MA, Rodriguez-Concepcion M. Carotenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: a colorful pathway. Arabidopsis Book. 2012;10:e0158. doi: 10.1199/tab.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandmann G. Evolution of carotene desaturation: the complication of a simple pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melendez-Martinez AJ, Mapelli-Brahm P, Benitez-Gonzalez A, Stinco CM. A comprehensive review on the colorless carotenoids phytoene and phytofluene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;572:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alagoz Y, Nayak P, Dhami N, Cazzonelli CI. cis-Carotene biosynthesis, evolution and regulation in plants: the emergence of novel signaling metabolites. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;654:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano G. Plant carotenoids: genomics meets multi-gene engineering. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;19:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Avalos J, Bonet ML, Boronat A, Gomez-Gomez L, Hornero-Mendez D, Limon MC, Melendez-Martinez AJ, Olmedilla-Alonso B, Palou A, et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog Lipid Res. 2018;70:62–93. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison EH, Quadro L. Apocarotenoids: emerging roles in mammals. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018;38:153–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-082117-051841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuzina V, Cerda-Olmedo E. Ubiquinone and carotene production in the Mucorales Blakeslea and Phycomyces. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:991–999. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roukas T. The role of oxidative stress on carotene production by Blakeslea trispora in submerged fermentation. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2016;36:424–433. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2014.989424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantzouridou F, Roukas T, Achatz B. Effect of oxygen rate on β-carotene production from synthetic medium by Blakeslea trispora in shake flask culture. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2005;37:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanou K, Roukas T. Waste cooking oil: a new substrate for carotene production by Blakeslea trispora in submerged fermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2016;203:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantzouridou FT, Naziri E. Scale translation from shaken to diffused bubble aerated systems for lycopene production by Blakeslea trispora under stimulated conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:1845–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mata-Gomez LC, Montanez JC, Mendez-Zavala A, Aguilar CN. Biotechnological production of carotenoids by yeasts: an overview. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Zada B, Wei G, Kim SW. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology approaches driving isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2017;241:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu FX, Lu Q, Bu YF, Liu JZ. Metabolic engineering for the microbial production of isoprenoids: carotenoids and isoprenoid-based biofuels. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2017;2:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Q, Fan F, Gao X, Yang C, Bi C, Tang J, Liu T, Zhang X. Balanced activation of IspG and IspH to eliminate MEP intermediate accumulation and improve isoprenoids production in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2017;44:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao P, Hemmerlin A, Bach TJ, Chye ML. The potential of the mevalonate pathway for enhanced isoprenoid production. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34:697–713. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon SH, Lee SH, Das A, Ryu HK, Jang HJ, Kim JY, Oh DK, Keasling JD, Kim SW. Combinatorial expression of bacterial whole mevalonate pathway for the production of b-carotene in E. coli. J Biotechnol. 2009;140:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coussement P, Bauwens D, Maertens J, De Mey M. Direct combinatorial pathway optimization. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:224–232. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, Zhu RY, Mitchell LA, Ma L, Liu R, Zhao M, Jia B, Xu H, Li YX, Yang ZM, et al. In vitro DNA SCRaMbLE. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1935. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03743-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HH, Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Sun ZZ, Xu G, Forest CR, Church GM. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature. 2009;460:894–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao J, Li Q, Sun T, Zhu X, Xu H, Tang J, Zhang X, Ma Y. Engineering central metabolic modules of Escherichia coli for improving b-carotene production. Metab Eng. 2013;17:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SY, Binkley RM, Kim WJ, Lee MH, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for high-level astaxanthin production with high productivity. Metab Eng. 2018;49:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyo KE, Ajikumar PK, Stephanopoulos G. Stabilized gene duplication enables long-term selection-free heterologous pathway expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:760–765. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Xiao W, Wang Y, Liu H, Li X, Yuan Y. Lycopene overproduction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through combining pathway engineering with host engineering. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:113. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong J, Park SH, Kim S, Kim SW, Hahn JS. Efficient production of lycopene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enzyme engineering and increasing membrane flexibility and NAPDH production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;103:211–213. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin J, Wang Y, Yao M, Gu X, Li B, Liu H, Ding M, Xiao W, Yuan Y. Astaxanthin overproduction in yeast by strain engineering and new gene target uncovering. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:230. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1227-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogure T, Inui M. Recent advances in metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for bioproduction of value-added aromatic chemicals and natural products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:8685–8705. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henke NA, Heider SAE, Hannibal S, Wendisch VF, Peters-Wendisch P. Isoprenoid pyrophosphate-dependent transcriptional regulation of carotenogenesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:633. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taniguchi H, Henke NA, Heider SAE, Wendisch VF. Overexpression of the primary sigma factor gene sigA improved carotenoid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum: application to production of b-carotene and the non-native linear C50 carotenoid bisanhydrobacterioruberin. Metab Eng Commun. 2017;4:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.meteno.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henke NA, Wiebe D, Perez-Garcia F, Peters-Wendisch P, Wendisch VF. Coproduction of cell-bound and secreted value-added compounds: simultaneous production of carotenoids and amino acids by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Bioresour Technol. 2018;247:744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naylor GW, Addlesee HA, Gibson LCD, Hunter CN. The photosynthesis gene cluster of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Photosynth Res. 1999;62:121–139. doi: 10.1023/A:1006350405674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi SC, Mothersole DJ, Dilbeck P, Niedzwiedzki DM, Zhang H, Qian P, Vasilev C, Grayson KJ, Jackson PJ, Martin EC, et al. Assembly of functional photosystem complexes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides incorporating carotenoids from the spirilloxanthin pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1847:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su A, Chi S, Li Y, Tan S, Qiang S, Chen Z, Meng Y. Metabolic redesign of Rhodobacter sphaeroides for lycopene production. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:5879–5885. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hara KY, Morita T, Endo Y, Mochizuki M, Araki M, Kondo A. Evaluation and screening of efficient promoters to improve astaxanthin production in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:6787–6793. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5727-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto K, Hara KY, Morita T, Nishimura A, Sasaki D, Ishii J, Ogino C, Kizaki N, Kondo A. Enhancement of astaxanthin production in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous by efficient method for the complete deletion of genes. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0556-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girard P, Falconnier B, Bricout J, Vladescu B. β-Carotene producing mutants of Phaffia rhodozyma. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;41:183–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00186957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollmann H, Breitenbach J, Sandmann G. Engineering of the carotenoid pathway in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous leading to the synthesis of zeaxanthin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Q, Jackson EN. Metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for industrial applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;36:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darvishi F, Ariana M, Marella ER, Borodina I. Advances in synthetic biology of oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for producing non-native chemicals. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:5925–5938. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matthaus F, Ketelhot M, Gatter M, Barth G. Production of lycopene in the non-carotenoid-producing yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1660–1669. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz C, Frogue K, Misa J, Wheeldon I. Host and pathway engineering for enhanced lycopene biosynthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2233. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao S, Tong Y, Zhu L, Ge M, Zhang Y, Chen D, Jiang Y, Yang S. Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes in Yarrowia lipolytica for heterologous b-carotene production. Metab Eng. 2017;41:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larroude M, Celinska E, Back A, Thomas S, Nicaud JM, Ledesma-Amaro R. A synthetic biology approach to transform Yarrowia lipolytica into a competitive biotechnological producer of b-carotene. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:464–472. doi: 10.1002/bit.26473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jang HJ, Yoon SH, Ryu HK, Kim JH, Wang CL, Kim JY, Oh DK, Kim SW. Retinoid production using metabolically engineered Escherichia coli with a two-phase culture system. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang HJ, Ha BK, Zhou J, Ahn J, Yoon SH, Kim SW. Selective retinol production by modulating the composition of retinoids from metabolically engineered E. coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1604–1612. doi: 10.1002/bit.25577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang C, Chen X, Lindley ND, Too HP. A “plug-n-play” modular metabolic system for the production of apocarotenoids. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:174–183. doi: 10.1002/bit.26462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Engelmann NJ, Clinton SK, Erdman JWJ. Nutritional aspects of phytoene and phytofluene, carotenoid precursors to lycopene. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:51–61. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollmann H, Breitenbach J, Sandmann G. Development of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous as a production system for the colorless carotene phytoene. J Biotechnol. 2017;247:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heider SA, Peters-Wendisch P, Wendisch VF, Beekwilder J, Brautaset T. Metabolic engineering for the microbial production of carotenoids and related products with a focus on the rare C50 carotenoids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:4355–4368. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobias AV, Arnold FH. Biosynthesis of novel carotenoid families based on unnatural carbon backbones: a model for diversification of natural product pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furubayashi M, Ikezumi M, Takaichi S, Maoka T, Hemmi H, Ogawa T, Saito K, Tobias AV, Umeno D. A highly selective biosynthetic pathway to non-natural C50 carotenoids assembled from moderately selective enzymes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7534. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brausemann A, Gemmecker S, Koschmieder J, Ghisla S, Beyer P, Einsle O. Structure of phytoene desaturase provides insights into herbicide binding and reaction mechanisms involved in carotene desaturation. Structure. 2017;25(1222–1232):e1223. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schaub P, Yu Q, Gemmecker S, Poussin-Courmontagne P, Mailliot J, McEwen AG, Ghisla S, Al-Babili S, Cavarelli J, Beyer P. On the structure and function of the phytoene desaturase CRTI from Pantoea ananatis, a membrane-peripheral and FAD-dependent oxidase/isomerase. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ye L, Zhu X, Wu T, Wang W, Zhao D, Bi C, Zhang X. Optimizing the localization of astaxanthin enzymes for improved productivity. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:278. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1270-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alonso-Gutierrez J, Koma D, Hu Q, Yang Y, Chan LJG, Petzold CJ, Adams PD, Vickers CE, Nielsen LK, Keasling JD, Lee TS. Toward industrial production of isoprenoids in Escherichia coli: lessons learned from CRISPR-Cas9 based optimization of a chromosomally integrated mevalonate pathway. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:1000–1013. doi: 10.1002/bit.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Lin Z, Huang C, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Tang YJ, Chen T, Zhao X. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR-Cas9 meditated genome editing. Metab Eng. 2015;31:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartz C, Shabbir-Hussain M, Frogue K, Blenner M, Wheeldon I. Standardized markerless gene integration for pathway engineering in Yarrowia lipolytica. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6:402–409. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Si T, Chao R, Min Y, Wu Y, Ren W, Zhao H. Automated multiplex genome-scale engineering in yeast. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15187. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jessop-Fabre MM, Jakociunas T, Stovicek V, Dai Z, Jensen MK, Keasling JD, Borodina I. EasyClone-MarkerFree: a vector toolkit for marker-less integration of genes into Saccharomyces cerevisiae via CRISPR-Cas9. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:1110–1117. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tarasava K, Oh EJ, Eckert CA, Gill RT. CRISPR-enabled tools for engineering microbial genomes and phenotypes. Biotechnol J. 2018;13:e1700586. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meadows AL, Hawkins KM, Tsegaye Y, Antipov E, Kim Y, Raetz L, Dahl RH, Tai A, Mahatdejkul-Meadows T, Xu L, et al. Rewriting yeast central carbon metabolism for industrial isoprenoid production. Nature. 2016;537:694–697. doi: 10.1038/nature19769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell K, Xia J, Nielsen J. The impact of systems siology on bioprocessing. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:1156–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Goh WWB, Wong L. Integrating networks and proteomics: moving forward. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34:951–959. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lechner A, Brunk E, Keasling JD. The need for integrated approaches in metabolic engineering. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a023903. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]