Abstract

Purpose of Review.

This synthesis of treatment research related to anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) focuses on the support for various forms of psychosocial interventions, useful adaptations to standard interventions, and engagement of candidate therapeutic mechanisms.

Recent Findings.

There is considerable evidence for the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to treat co-occurring problems with anxiety, in the context of relatively little research on treatment of co-occurring depression. Multiple mechanisms of treatment effect have been proposed, but there has been little demonstration of engagement via experimental therapeutics.

Summary.

Comorbidity between ASD and anxiety and/or mood problems is common. Although there is evidence for the use of CBT for anxiety, little work has addressed how to effectively treat depression. There is emerging support for alternative treatment approaches, such as mindfulness-based interventions. We encourage rigorous, collaborative approaches to identify and manipulate putative mechanisms of change.

Keywords: autism, intervention, anxiety, depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects approximately 1 in 59 children in the United States [1]. It is widely accepted that co-occurring psychiatric disorders are common in autistic adolescents and adults. One in two people on the spectrum is affected by a co-occurring anxiety or depressive disorder [2–4]. Among people with ASD who do not also have intellectual disability, anxiety and depression are among the most common co-occurring mental health problems.

Problems with anxiety and depression confer unique impairment, above and beyond what is associated with ASD. Among neurotypical adults, both anxiety and depression have been found to predict poorer quality of life [5]. Similarly, these co-occurring conditions have been associated with increased service use, caregiver burden, and decreased quality of life in ASD [6–8]. In adults with ASD, there is evidence that ASD severity moderates impact of anxiety such that anxiety has a greater adverse impact on outcome among people who are less severely affected by autism [8]. Relative to anxiety in autism, there is little research on the experience or impact of depression.

Although there has been relatively little longitudinal research, prospective studies have shown that social communication impairment, a hallmark feature of ASD, predicts heightened risk of social anxiety longitudinally among typically developing children [9]. One of the few longitudinal studies with children with ASD found that anxiety predicted social communication impairment; however, social communication deficits did not increase risk for anxiety [10]. Much remains to be learned about the potentially transactional relationship between core features of ASD and anxiety and mood disturbance.

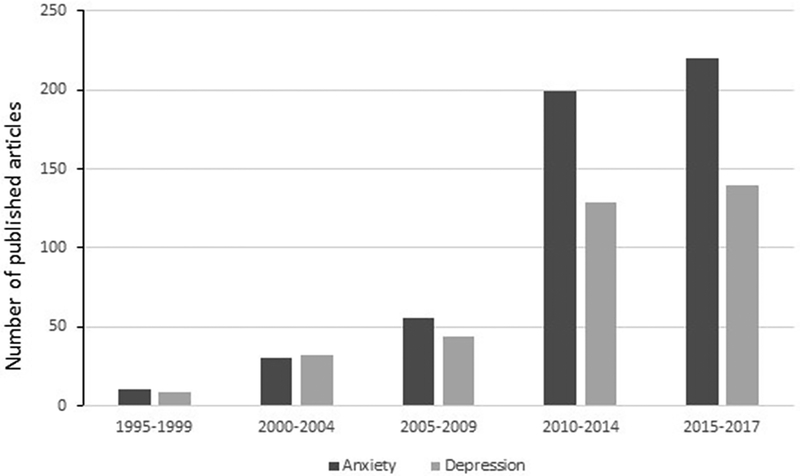

Given the frequency with which anxiety and depression co-occur in ASD, in conjunction with their unique impact on functioning, adult outcome, and quality of life, it is critical to consider how to best prevent and treat these disorders among adolescents and adults with ASD. The past 20 years has seen rapid proliferation of scientific and clinical interest in anxiety in autism, as exemplified by an approximately 30-fold increase in rate of publication on this topic [11]. Although research on depression has proceeded at a slower rate, there has been heightened basic and clinical research in this area as well [12]. At this juncture, there is a suitable research base to guide evidence-based care decisions related to treatment of anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults with ASD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of research articles published in 5-year increments [last block is 3-year increment]. Articles were retrieved from PUBMED. Search terms were restricted to title or abstract [autism OR asperger* AND treatment AND ‘anxiety’/’depression’]

Treatment of Anxiety and Depression ASD

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health condition among children and adolescents, and they are associated with significant impairment in family, social, academic, and adaptive functioning [13]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which involves exposure, modeling, and parental involvement, has been labeled a “well-established” evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults [13]. Among adults, depression is the most prevalent mental health condition worldwide [14], and a recent meta-analytic review suggests that individuals with ASD are four times more likely to experience depression in their lifetimes than are typically developing counterparts [12]. First onset is often during adolescence and it is associated with significant impairment in global life domains [15]. Among adolescents in the general population, CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) have been deemed “well-established” evidence-based treatments for depression with medium effect size response rates, as well as “probably efficacious” for children [16].

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The majority of existing research on co-occurring psychiatric conditions in ASD has focused upon anxiety reduction among higher functioning children and adolescents with ASD. To date, more than 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adapted CBT for anxiety have been published. CBT studies have been conducted in group [17], individual [18–19], and mixed group/individual [20] modalities. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have recently been conducted [21–25], generally finding moderate to large treatment effects [21, 23–24].

In comparison to anxiety, there has been far less research on the psychosocial treatment of depression in ASD. A recent meta-analysis of RCTs examining CBT use in ASD found that most studies only emphasized anxiety [26]. The few trials that targeted a problem other than anxiety involved treatment of anger, emotion dysregulation, insomnia, or OCD; none explicitly targeted depression [26]. Although it is often assumed that CBT (with more general, rather than anxiety-specific, protocols) would also be beneficial to treat depression in ASD, there is limited direct evidence for this assumption. Interestingly, a recent quasi-experimental design of group CBT with adolescents and young adults with ASD found that depression improved whereas anxiety did not [27].

Mindfulness and Non-CBT Psychosocial Approaches

More recently, non-CBT approaches, such as mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) have been applied successfully with clients with ASD, with preliminary evidence suggesting that MBI has the potential to reduce the impact of co-occurring anxiety and depression [28]. There is a sizable body of research suggesting that improved emotion regulation and increased emotional awareness are primary treatment mechanisms in MBI [29]. These mechanisms provide an attractive alternative for autistic adolescents and adults, as high-level cognitive strategies taught in CBT can be difficult to deploy during times of high distress. There is growing interest in utilizing and adapting MBI for adolescents and adults with ASD [28, 30].

To our knowledge, only one RCT utilizing MBI with adults with ASD has been published. Spek and colleagues [31] utilized modified MBI group treatment with 42 adults with comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms, and results included large effect decreases in anxiety and depression symptoms. Similarly, in a second open trial with 50 adults with ASD, reductions in anxiety and depression were observed and maintained at the 9-week follow-up [32]. Sizoo and Kuiper utilized a group-based MBI with autistic adults and found large effects in anxiety reduction and depression [33]. Of note, they used an unmatched and uncontrolled design, in which adults with ASD completed either group CBT or a group MBI program, and both were found to reduce depression with no significant difference between the conditions [33]. To date, there are no studies that utilize an individual MBI modality for adults with ASD that targets depression or anxiety. However, Conner & White conducted an open trial with an MBI that utilized individual therapy to target emotion dysregulation broadly; results supported both feasibility and preliminary efficacy [30].

MBI research with adolescents with ASD has primarily involved parent training to reduce problem behaviors (e.g., aggression) [34–41]. These studies support the utility of both group and individual parent-assisted MBI with children and adolescents with ASD. Much of this research reports promising results with respect to reduction of aggression and problem behaviors, but none have studied co-occurring depression and anxiety as primary outcomes [35].

Other psychosocial interventions targeting core ASD symptomatology have demonstrated indirect effects upon depression and anxiety symptoms. For example, the PEERS social skills group program for adolescents and young adults [42] has been shown to reduce depression and suicidality among teens [43] and social anxiety symptoms have likewise decreased significantly for young adults following PEERS [44]. Beyond psychosocial treatments, medication utilization for anxiety and depression symptoms is high in this population, especially among those with co-occurring ID. One survey found that at least 50% of adolescents and adults with ASD were prescribed antidepressants [45]. In a recent evaluation of Medicaid claims data, adults with ASD who had depression or anxiety were actually less likely to receive psychosocial intervention than adults with depression or anxiety without ASD, yet more than twice as likely to be on multiple psychotropic medications [46]. This is noteworthy given the limited research base on their impact, and also given there are no FDA-approved medications to treat anxiety and depression in ASD [47].

Common Treatment Modifications

Regardless of the intervention approach, it is generally agreed that some adaptation is helpful to make the content more relevant and digestible for clients with ASD. It is our understanding that there are more similarities than differences across studies and protocols, with respect to content and delivery adaptations. Such adaptations include heightened parental involvement, increased use of structure and visuals (worksheets, role plays, visual cues and prompts, etc.), concrete examples and language, and increased psychoeducation on emotions and anxiety. Moree and Davis [48] identified four common modifications for CBT with children with ASD and co-occurring anxiety: (1) concrete tools and supports; (2) use of hierarchies that also address ASD symptoms; (3) incorporation of special interests; and (4) parental involvement.

Clinicians may choose to weight some CBT-based therapy more heavily on the behavioral side, particularly in those individuals with reduced verbal competency, and those who struggle with cognitive flexibility or generalizing learned skills across situations. In such scenarios, behavioral strategies may be more valuable than cognitive approaches, and might focus on building adaptive behaviors, structuring time and providing accountability, identifying and working toward life goals, increasing social opportunities and other rewards, and to some extent supporting healthy behaviors relevant to sleep, exercise, and nutrition. Such foci may be particularly helpful for emerging adults or transition-age youth moving from highly structured education systems, often with services/supports, to minimally structured, experientially impoverished lives essentially “overnight” [49].

Common modifications for MBI with adolescents and adults with ASD include the elimination of metaphors and poetry and changing lengths of meditations to account for slow processing and attentional capacity [30–32]. Many interventions also incorporate an emphasis on social problems and other core ASD characteristics while targeting the reduction of anxiety or depressive symptoms. Core symptoms of ASD have been included with anxiety symptoms on symptom hierarchies [19], and group-based skills training and practice can be used to leverage heightened social interest as well as anxiety reduction [20]. While parental involvement in treatment typically decreases from childhood to adolescence, individuals with ASD are likely to depend more upon parents or other caregivers into adulthood. Therefore, including parents and caregivers in interventions has been recommended as a means to increase generalizability of core concepts taught in the therapy session [50]. Additional time to structure and plan practice tasks is often warranted to combat executive functioning deficits (e.g., planning, time management). For instance, a therapist might, in collaboration with the client and his parents, make a concrete plan for completing homework and provide a structured worksheet to complete and return at the next session. We summarize the most commonly seen adaptations in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common Modifications When Treating Anxiety or Depression in Clients with ASD

| Domain | Modification |

|---|---|

| Content | Focus on positive character attributes of client during treatment, in consideration of chronic nature of ASD |

| Address ASD core symptoms/deficits during treatment (e.g., in developing exposure hierarchy, targeting social problems) Use supplemental group training for additional skills practice/modeling |

|

| Use of peers or similar-age others for modeling, and skills practice | |

| Increased focus on developing emotional awareness/insight | |

| Delivery | Increased reliance on parents (throughout treatment, and with adolescent/young adult clients) |

| Psychoeducation on relationship between autism and anxiety/depression | |

| Slower pace of treatment (to allow for processing time and repetitive practice) | |

| Inclusion of special interests in treatment (e.g., to teach and incentivize) | |

| Eliminate or reduce use of metaphors (for some clients) | |

| Highly structured sessions, clear expectations | |

| Use of visuals for teaching and support during session (e.g., handouts) | |

| Additional time for in-session practice and planning at-home practices |

Identifying and Engaging Common Factors

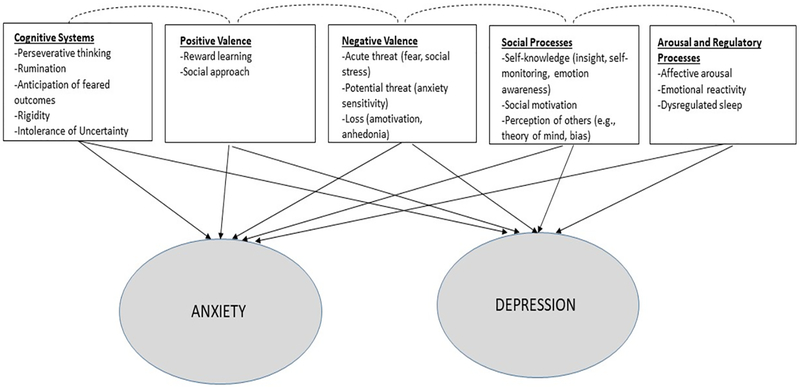

Despite the growing body of research demonstrating the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for anxiety and depression in people with ASD, this research base has generally adopted a fairly traditional focus on clinical response, rather than engagement of targeted mechanisms of action. Owing in part to an appreciation of the lack of clear boundaries distinguishing different psychiatric disorders, intervention research has experienced a shift toward identification of mechanisms underlying psychopathology, which may or may not be tethered to particular diagnoses. Consistent with this shift in thinking about psychopathology is a call for experimental therapeutics approaches that involve identification of the candidate mechanism before evaluation of clinical impact. Such target-based approaches are thought to promote a richer understanding of mediators and moderators of treatment change, as well as greater transdiagnostic portability [51]. To inform future treatment research in this area, we pull from the extant treatment literature to propose specific constructs, or mechanisms of action, that warrant consideration (Figure 2). These candidate mechanisms are couched in the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) matrix, espoused by the National Institute of Mental Health [52]. RDoC provides a framework for the consideration of psychological constructs that may be informative across psychiatric disorders, broken down into the following five major domains: Cognitive systems; Negative Valence Systems (related to aversive situations including fear, anxiety, and loss); Positive Valence Systems (related to motivation, reward seeking, etc.); Systems for Social Processes; and Arousal/Regulatory Systems. Although RDoC emphasizes the integration of multiple levels of information including genetics, neural functioning, and physiology, below we primarily focus on behavioral research and emphasize components of the RDoC matrix that might be most relevant to anxiety and depression in ASD.

Figure 2.

Candidate treatment mechanisms associated with NIMH RDoC domains

Cognitive Systems

Several constructs within the Cognitive Systems domain of RDoC have been considered in anxiety and depression research in ASD. These include perseverative thinking and rumination, rigidity, intolerance of uncertainty, and fear of bad outcomes or negative evaluation by others. Indeed, some of these processes are already targeted in treatment research: most of the CBT programs evaluated to date in ASD make reference to isolating processes such as testing the probability of the feared (bad) outcomes during cognitive restructuring [19, 53–54].

Other constructs that have been linked to anxiety and depression, namely indecision and perseverative thinking, have not yet been well-addressed in the treatment literature. People with ASD often struggle with decision-making [55], especially with day to day decision-making and when the decision must be made quickly. The decision-making approach of young people with ASD tends to be characterized by a drive to avoid potential loss [56]. This is different from the general neurotypical stance of seeking (or approaching) potential reward, even in the face of risk. Although a risk avoidance technique is logical, it is not always ideal for everyday social interactions in which some level of risk is inherent [55]. To the extent that aberrant decision-making leads to behavioral avoidance, it may be linked to anxiety or depression via reduced opportunity for rewarding experiences that promote social growth [57].

Diminished reward sensitivity and approach motivation have been long-associated with anhedonia and clinical depression, as well as other internalizing disorders [58–59]. In the adult ASD population, recent evidence suggests that diminished sensitivity to social reward is associated with loneliness, and loneliness in turn predicts depression [60]. Within the same study, an interactive effect was observed in which greater self-reported capacity for social reward was also strongly associated with loneliness in the specific context of elevated social impairment. This may suggest that interplay between cognitive features and environmental context (e.g., social opportunities) moderates internalizing symptoms in ASD.

Perseverative and passive (unproductive) thinking on negative topics (generally called rumination) is robustly associated with the onset of depressive disorders in the typically developing population [51]. Rumination correlates with more “autism-specific” markers of perseveration, such as insistence on sameness, across ASD and general samples [61–63], and ruminative thinking has been shown to prospectively predict greater depressive symptoms in children with ASD [64]. Gotham and colleagues recently observed similarity in a potential neural signature of rumination across adults with ASD and typically developing depressed adults [65]. They concluded that depression treatments in ASD are likely to profit from following models used in other ruminative populations. Finally, intolerance of uncertainty has been suggested as a mediator of anxiety in people with ASD. Boulter and colleagues [66] found that intolerance of uncertainty was elevated in youth with ASD, relative to peers without ASD. They also found support for intolerance of uncertainty as a mediator between ASD and anxiety; however, given the use of a non-experimental design, neither causation nor temporal precedence could be established.

Positive and Negative Valence Systems

In contrast to the variety of cognitive constructs that have been explored in research on anxiety and depression in ASD, the RDoC domain of Positive Valence Systems and Negative Valence Systems has not been widely studied. Negative Valence Systems have most often been considered in relation to potential threat, which underlies the majority of CBT-based anxiety treatment and is targeted directly in ASD treatment protocols that include exposures [17, 19]. However, one study examining attention bias to threatening stimuli found no significant differences in bias between ASD and non-ASD groups and no association between bias and anxiety [67].

The RDoC construct of loss offers another avenue for future work attempting to identify intervention targets, insofar as it relates to such concepts as anhedonia and amotivation. Anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure, is more prevalent in ASD relative to typically developing groups, and to be a primary contributor of depressive symptoms [68]. Loss, as it refers to the occurrence of negative life events, has also been reported in adults with ASD; negative life events were also correlated with overall depression and anxiety [69–70]. The frequency of these events and their impact on internalizing symptomatology may be related to negative attributional styles or patterns of cognitive rigidity and rumination unique to ASD [61, 71].

Within the Positive Valence Systems, social motivation models of ASD have suggested that approach motivation and reward learning function differently in ASD, such that social stimuli are less rewarding for individuals on the spectrum, which results in decreased neural specialization for efficient processing of social stimuli [72]. Although social approach and reward have not often been evaluated in treatment studies, children with ASD have been found to self-report less social interest but more approach to social stimuli during a behavioral task, compared to children without ASD [73]. Additional work has established relationships among social communication and facial emotion recognition deficits, social interest, and loneliness [60, 74–75]. An emerging body of evidence indicating that social reward varies within ASD (e.g., sub-groups based on social reward and motivation) and the extent to which social approach and reward might both underlie anxiety and depression and be responsive to intervention suggests this is an important, untapped avenue of research. New work also indicates that, even within the context of social orienting, individuals with ASD and individuals with depression may share a visual attention bias away from positive emotions specifically, which represents another area to explore for links to emotional well-being [76].

Systems for Social Processes

Regarding the RDoC domain of Systems for Social processes, relevant targets of treatment for depression and anxiety in individuals with ASD have included self-monitoring, emotion recognition, insight, and theory of mind (i.e., expressed empathy). Few studies have sought to isolate and evaluate these constructs as components of treatment for anxiety and depression. In a recent study, Pallathra and colleagues examined social motivation, social cognition, social skills, and social anxiety in adults with ASD; the authors reported nonsignificant associations between these behavioral components of social functioning and anxiety, suggesting a multidimensional model of social functioning [77]. Social motivation was associated with both social skill and social anxiety, which suggests the potential mechanistic import of social motivation.

Self-monitoring, wherein individuals are taught skills to manage their own behavior, has been shown to successfully improve social/adaptive/academic difficulties in individuals with ASD, although there is large variability in implementation [78]. CBT, which integrates elements of self-monitoring and emotion recognition, has successfully been shown to reduce anxiety in children with ASD [19]. Furthermore, modifications to CBT, such as the addition of social skill work (i.e., didactic lessons, peer modeling, behavioral rehearsal, etc.) also show promise in targeting symptoms of anxiety in conjunction with social skills [20, 79].

Considering the association, though debated, between social communication impairment and anxiety in individuals with ASD [9–10], attention should also be given to underlying mechanisms of social skills training (SST) in treating anxiety and depression in individuals with ASD. SST addresses social processes holistically, integrating didactic lessons, peer modeling, and behavioral rehearsal. Findings regarding the efficacy of SST to address anxiety and depression are mixed; several reviews of SST highlight unsuccessful attempts to address anxiety [80] and depression [81] as secondary treatment targets. In contrast, researchers examining the impact of a theatre-based SST intervention reported a concurrent decrease in anxiety in individuals with ASD [82] and group-based SST contributed to reduced depression linked to increased social contact [43]. In each of these studies, outcomes addressing Systems for Social Processes (i.e., emotion recognition, empathy, social motivation, insight, etc.) were measured using behavioral and questionnaire instruments and the interventions were multicomponent, which does not permit us to unpack the relative impact of isolated constructs or mechanisms.

Arousal & Regulatory Systems

Emotional reactivity falls within the Arousal and Regulatory Systems domain of the RDoC. Conceptualized as the tendency to experience strong, often sudden, negative emotion, emotional reactivity is tethered to emotion regulation in typically developing [83] and ASD [84] samples. Emotion dysregulation, or difficulty altering one’s emotions in adaptive or goal-directed ways, has been shown to be impaired in many psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression, in people without [85] and with ASD [86]. There have been recent strides made in the valid assessment of emotion dysregulation in people with ASD [84]; as such, emotional reactivity/emotion dysregulation are prime candidates for further exploration in treatment research. In a recent two-site open trial of a therapy developed to improve emotion regulation in adolescents with ASD, of 17 treatment completers, all showed meaningful improvement on at least one index of emotion regulation and most (94%) had meaningful reduction in depression, anxiety, or problem behaviors [30].

Sleep is another primary focus of the Arousal and Regulatory Systems in the RDoC framework. Dysregulated sleep has been linked to anxiety and depression across clinical populations, with suggested bidirectional effects [87]. As sleep problems are highly prevalent in ASD and have been associated with behavioral problems [88], this is an important direction for future study as an intermediate and moveable mechanism in ASD treatments for anxiety and depression.

Conclusions

Among adolescents and adults with ASD, both anxiety and depression are highly prevalent. These co-occurring conditions confer additional impairment and therefore warrant targeted treatment. There has been rapid growth in psychosocial treatment research in this area, though most of this work has focused on the application of CBT to anxiety. In recent years, other approaches, such as mindfulness-based treatments, have been garnering more research attention. Based on this state of this research, there is reason to be optimistic about our ability to successfully treat anxiety and depression in clients with ASD.

An experimental therapeutics approach to treatment development [89] holds that a specific disease mechanism must be identified and found to be modifiable prior to evaluation of treatment efficacy, operationalized as change in more distal, clinical outcomes. Given the heightened federal focus [52] on experimental therapeutics and a growing scientific appreciation of the utility of transdiagnostic treatments, we have endeavored to identify the most promising candidate mechanisms related to treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with ASD. Our hope is that this review will serve as a guide for future treatment research in this area, and note that neither the RDoC domains nor the constructs housed within are orthogonal to one another; many are inter-related (Figure 2).

We are making progress toward understanding why and under what conditions treatment works [90]. As treatment research for co-occurring problems in people with ASD matures, we encourage early identification of putative mechanism(s) of change. It is equally important to consider study designs (e.g., longitudinal; use of multiple and multi-unit assessments of key mechanisms and outcomes; sufficiently large sample size to explore moderation) that will allow us to answer critical questions related to ‘why, when, and for whom’ treatment effects are seen.

Contributor Information

Susan W. White, Department of Psychology, Virginia Tech, 460 Turner St., Suite 207, Blacksburg, VA 24060, sww@vt.edu

Grace Lee Simmons, Department of Psychology, Virginia Tech

Katherine O. Gotham, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Caitlin M. Conner, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Isaac C. Smith, Department of Psychology, Virginia Tech

Kelly B. Beck, Clinical Rehabilitation and Mental Health Counseling, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences

Carla A. Mazefsky, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

References

*Of importance (published within last 3 years)

**Of major importance (published within last 3 years)

- 1.Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years–Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018:67(No. SS-6):1–23. Doi:0.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepburn SL, Stern JA, Blakeley-Smith A, Kimel LK, Reaven JA. Complex psychiatric comorbidity of treatment-seeking youth with autism spectrum disorder and anxiety symptoms. J Ment Health Res in Intellect Disabil 2014:7(4):359–378. Doi: 10.1080/19315864.2014.932476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofvander B, Delorme R, Chaste P, Nydén A, Wentz E, Ståhlberg O, et al. Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2009. December:9(1). Doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maddox BB, White SW. Comorbid social anxiety disorder in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2015:45(12):3949–3960. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2531-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olatunji BO Cisler JM, Tolin DF. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2007:27:572–81. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadman T, Eklund H, Howley D, Hayward H, Clarke H, Findon J, et al. Caregiver burden as people with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder transition into adolescence and adulthood in the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012:51:879–888. Doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi G, Wozniak J, Petty C, Martelon MK, Fried R, Bolfek A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and functioning in a clinically referred population of adults with autism spectrum disorders: A comparative study. J Autism Dev Disord 2012:43:1314–1325. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1679-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8*.Smith IC, Ollendick TH, White SW. Anxiety moderates the influence of asd severity on quality of life in adults with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord (under review). [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Pickard H, Rijsdijk F, Happé F, Mandy W. Are Social and Communication Difficulties a Risk Factor for the Development of Social Anxiety? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017:56(4):344–351. Doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Duvekot J, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, & Greaves-Lord K. Examining bidirectional effects between the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) core symptom domains and anxiety in children with ASD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl 2017:59(3). Doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Vasa RA, Keefer A, Reaven J, South M, White SW. Priorities for advancing research on youth with autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring anxiety. J Autism Dev Disord 2018:48:925–934. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3320-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Hudson CC, Hall L, Harkness KLJ. Prevalence of depressive disorders in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Abnorm Child Psychol 2018. Doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0402-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higa-McMillan CK, Francis SE, Rith-Najarian L, Chorpita BF. Evidence base update: 50 years of research on treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2018:45(2):91–113. Doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1046177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith K Mental health: A world of depression: A global view of the burden caused by depression. Nat 2014:515:180–181. Doi: 10.1038/515180a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: The Zurich Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003:60(10): 993–1000. Doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KTG, Bolano C. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression, J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016:46(1):11–43. Doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Leuthe E, Moody E, Hepburn S. Facing your fears in adolescence: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety. Autism Res Treat 2012:1–13. Doi: 10.1155/2012/423905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS., Dane BF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depress Anxiety 2015:32(3):174–181. Doi: 10.1002/da.22332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl 2009:50(3):224–34. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, et al. Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2013:43(2):382–394. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Kreslins A, Robertson AE, Melville C. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Health 2015:9(1):22 Doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0054-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Lietz P, Kos J, Dix K, Trevitt J, Uljarevic M, O’Grady E. Protocol for a systematic review: Interventions for anxiety in school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A mixed-methods systematic review. Campbell Corporation. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sukhodolsky DG, Bloch MH, Panza KE, Reichow B. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: A meta-analysis. Pediatr 2013:132(5):e1341–e1350. Doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ung D, Selles R, Small BJ, Storch EA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2014:533–547. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Vasa RA, Carroll LM, Nozzolillo AA, Mahajan R, Mazurek MO, Bennett AE et al. A systematic review of treatments for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2014:44(12):3215–3229. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2184-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Weston L, Hodgekins J, Langdon PE. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016:49:41–54. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGillivray JA, Evert HT. Group cognitive behavioural therapy program shows potential in reducing symptoms of depression and stress among young people with ASD J Autism Dev Disord 2014:44:2041–2051. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2087-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Cachia R, Anderson AM, Dennis W. Mindfulness, stress and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J Child Fam Stud 2016:25(1):1–14. Doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0193-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of meditation studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2015:37:1–12. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conner CM, White SW. Brief report: Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of individual mindfulness therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2017: 48, 290–300. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3312-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spek A, van Ham N, Nyklicek I. Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Res Dev Disabil 2013. January: 34(1): 246–253. Doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiep M, Spek AA, Hoeben L. Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Do treatment effects last? Mindfulness 2015:6(3):637–644. Doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0299-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Sizoo BB, Kuiper E. Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness based stress reduction may be equally effective in reducing anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil 2017:64:47–55. Doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bruin E, Blom R, Smit F, van Steensel F, Bogels S. MYmind: Mindfulness training for youngsters with autism spectrum disorders and their parents. Autism 2015:19(8):906–914. Doi: 10.1177/1362361314553279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Hourston S Atchley R. Autism and mind-body therapies: A systematic review. J Altern Complement Med 2017:23(5):331–339. Doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang Y, Kearney PA. A mindfulness intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: New directions in research and practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. Doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18962-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang Y, Kearney P, Klieve H Lang W, Roberts J. Cultivating mind: Mindfulness interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder and problem behaviours, and their mothers. J Child Fam Stud 2015:24(10):3093–3106. Doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0114-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pahnke J, Lundgren T, Hursti T, Hirvikoski T. Outcomes of an acceptance and commitment therapy-based skills training group for students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A quasi-experimental pilot study. Autism 2014:18(8):953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Manikam R, Winton ASW, Singh ANA, Singh J, et al. A mindfulness-based strategy for self-management of aggressive behavior in adolescents with autism. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2011:5:1153–1158. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Singh ADA, Winton ASW, Singh ANA, Singh J. Adolescents with Asperger syndrome can use a mindfulness-based strategy to control their aggressive behavior. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2011:5:1103–1109. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Curtis WJ, Wahler RG, Sabaawi M, et al. Mindful staff increase learning and reduce aggression in adults with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2006:27:545–558. Doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laugeson EA, Frankel F, Gantman A, Dillon AR, Mogil C. A randomized controlled study of parent-assisted children’s friendship training with children having autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2012:42:1025–1036. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Schiltz HK, McVey AJ, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, Karst JS, et al. Changes in depressive symptoms among adolescents with ASD completing the PEERS® Social Skills Intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018:48(3):834–43. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3396-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McVey AJ, Schiltz H, Haendel A, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, et al. Brief Report: Does gender matter in intervention for ASD? Examining the impact of the PEERS® Social Skills Intervention on social behavior among females with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017:47(7):2282–2289. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3121-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lake JK, Vogan V, Sawyer A, Weiss JA, Lunsky Y. Psychotropic medication use among adolescents and young adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Parent views about medication use and healthcare services. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2015:25(3):260–268. Doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Maddox BB, Kang-Yi CD, Brodkin ES, Mandell DS. Treatment utilization by adults with autism and co-occuring anxiety or depression. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2018:51:32–37. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel M, Beaulieu AA. Psychotropic medications in children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and synthesis for evidence-based practice. J Autism Dev Disord 2012:42:1592–1605. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moree BN, Davis TE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: Modification trends. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2010:4(3):346–354. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49*.Taylor JL, Adams RE, Bishop SL. Social participation and its relation to internalizing symptoms among youth with autism spectrum disorder as they transition from high school. Autism Res 2017:10(4):663–672. Doi: 10.1002/aur.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Kerns CM, Roux AM, Connell JE, Shattuck PT. Adapting cognitive behavioral techniques to address anxiety and depression in cognitively able emerging adults on the autism spectrum. Cogn Behav Pract 2016:23(3):329–340. Doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008:3:400–24. Doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.National Institutes of Health. RDoC Snapshot: Version 3. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/constructs/rdoc-snapshot-version-3-saved-5-18-2017.shtml

- 53.Chalfant AM, Rapee R, Carroll L. Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 2007:37:1842–1857. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0318-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S. A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005:46(11):1152–60. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grandin T My mind is a web browser: How people with autism think. Cerebrum 2000:2:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 56.South M, Chamberlain PD, Wigham S, Newton T, Le Couteur A, McConachie H, et al. Enhanced decision making and risk avoidance in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychol 2014:28:222–228. Doi: 10.1037/neu0000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimidjian S, Barrera M, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011:7:1–38. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nelson BD, Kessel EM, Klein DN, Shankman SA. Depression symptom dimensions and asymmetrical frontal cortical activity while anticipating reward. Psychophysiol 2017:55:e12892 Doi: 10.1111/psyp.12892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma A, Wolf DH, Ciric R, Kable JW, Moore TM, Vandekar S. et al. Common dimensional reward deficits across mood and psychotic disorders: A connectome-wide association study. Am J Psychiatry 2017:174:657–66. Doi: 10.1176//appi.ajp.2016,16070774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60*.Han G, Gotham K. Social reward profiles and their relation to loneliness and depressed mood in adults with autism spectrum disorder. (under review).

- 61.Gotham K, Bishop SL, Brunwasser S, Lord C. Rumination and perceived impairment associated with depressive symptoms in a verbal adolescent–adult ASD sample. Autism Res 2014:7(3):381–391. Doi: 10.1002/aur.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62**.Keenan EG, Gotham K, Lerner MD. Hooked on a feeling: Repetitive cognition and internalizing symptomatology in relation to autism spectrum symptomatology. Autism 2017. Doi: 10.1177/1362361317709603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63**.Patel S, Day TN, Jones N, Mazefsky CA. Association between anger rumination and autism symptom severity, depression symptoms, aggression, and general dysregulation in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017:21(2):181–189. Doi: 10.1177/1362361316633566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rieffe C, De Bruin M, De Rooij M, Stockmann L. Approach and avoidant emotion regulation prevent depressive symptoms in children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014:39:37–43. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Gotham K, Siegle G, Han G, Tomarken A, Crist R, Simon D, Bodfish J. Pupil response to social-emotional materials is associated with rumination and depressive symptoms in adults with autism spectrum disorder. PLOS One (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boulter C, Freeston M, South M, Rodgers J. Intolerance of uncertainty as a framework for understanding anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014:44(6):1391–1402. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-2001-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hollocks MJ, Ozsivadjian A, Matthews CE, Howlin P, Simonoff E. The relationship between attentional bias and anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res 2013:6(4):237–247. Doi: 10.1002/aur.1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bitsika V, Sharpley CF. Differences in the prevalence, severity and symptom profiles of depression in boys and adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder versus normally developing controls. Int J Disabil Dev Educ 2015:62(2):158–167. Doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2014.998179+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Bruggink A, Huisman S, Vuijk R, Kraaij V, Garnefski N. Cognitive emotion regulation, anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2016:22:34–44. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70*.Taylor JL, Gotham KO. Cumulative life events, traumatic experiences, and psychiatric symptomatology in transition-aged youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Neurodev Disord 2016:8(1):28 Doi: 10.1186/s11689-016-9160-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barnhill GP, Myles BS. Attributional style and depression in adolescents with Asperger syndrome. J Posit Behav Interv 2001:3(3):175–182. Doi: 10.1177/109830070100300305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci 2012:16(4):231–239. Doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deckers A, Roelofs J, Muris P, Rinck M. Desire for social interaction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectrum Disord, 2014:8(4):449–453. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74**.Deckers A, Muris P, Roelofs J. Being on your own or feeling lonely? Loneliness and other social variables in youths with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2017:48(5):828–839. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0707-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75**.Garman HD, Spaulding CJ, Webb SJ, Mikami AY, Morris JP, Lerner MD. Wanting it too much: an inverse relation between social motivation and facial emotion recognition in autism spectrum disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2016:47(6):890–902. Doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0620-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76**.Unruh K, Bodfish J, Gotham K. Adults with autism and adults with depression show similar attentional biases to social-affective images. J Autism Dev Disord (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77**.Pallathra AA, Calkins ME, Parish-Morris J, Maddox BB, Perez LS, Miller J, et al. Defining behavioral components of social functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder as targets for treatment: Components of social functioning in adult ASD. Autism Res 2018:11(3):488–502. Doi: 10.1002/aur.1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aljadeff-Abergel E, Schenk Y, Walmsley C, Peterson SM, Frieder JE, Acker N. The effectiveness of self-management interventions for children with autism—A literature review. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2015:18:34–50. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sze KM, Wood JJ. Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorders and social difficulties in children with high-functioning autism: A case report. J Contemp Psychother 2007:37(3):133–43. Doi: 10.1007/s10879-007-9048-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oswald TM, Winder-Patel B, Ruder S, Xing G, Stahmer A, Solomon M. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the ACCESS Program: A group intervention to improve social, adaptive functioning, stress coping, and self-determination outcomes in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2018:48(5):1742–60. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3421-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reichow B, Steiner AM, Volkmar F. Cochrane Review: Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Evid-Based Child Health: Cochrane Rev J. 2013:8(2):266–315. Doi: 10.1002/ebch.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82*.Corbett BA, Blain SD, Ioannou S, Balser M. Changes in anxiety following a randomized control trial of a theatre-based intervention for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017:21(3):333–43. Doi: 10.1177/1362361316643623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zelkowitz RL, Cole DA. Measures of emotion reactivity and emotion regulation: Convergent and discriminant validity. Personal Individ Differ 2016:102:123–132. Doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84*.Mazefsky CA, Yu L, White SW, Siegel M, Pilkonis PA. The emotion dysregulation inventory: Psychometric properties and item response theory calibration in an autism spectrum disorder sample: Emotion dysregulation inventory. Autism Res. 2018. Doi: 10.1002/aur.1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010:30(2):217–37. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weiss JA, Riosa PB, Mazefsky CA, Beaumont R. Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder In Essau CA, LeBlanc SS, Ollendick TH, editors. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology in Children and Adolescents. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013:36(7):1059–1068. Doi: 10.5665/sleep.2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goldman SE, McGrew S, Johnson KP, Richdale AL, Clemons T, Malow BA. Sleep is associated with problem behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 2013:5(3):1223–1229. Doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89**.Lewandowski KE, Ongur D, Keshavan MS. Development of novel behavioral interventions in an experimental therapeutics world: Challenges, and directions for the future. Schizophr Res 2018:192:6–8. Doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lerner MD, White SW, McPartland JC. Mechanisms of change in psychosocial interventions for autism spectrum disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2012:14(3):301–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]