Abstract

Background:

The standard treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) had been rituximab-based immunochemotherapy. However, the biological and clinical heterogeneity within DLBCL seems to affect treatment outcome. Therefore, the evaluation of miRNA levels might be useful in predicting treatment response and relapse risk. miR-146a is a modulator of innate and acquired immunity and may play an important role in predicting treatment response. The aim of the present study was to compare the expression level of miR-146a in plasma-derived exosomes of responsive DLBCL patients (response to R-CHOP (Rituximab, and Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovine and Prednisone)), refractory DLBCL patients (resistant to R-CHOP), patients receiving R-CHOP, and healthy donors.

Materials and Methods:

After the preparation of plasma and isolation of exosomes, the presence of plasma-derived exosome was confirmed by Zetaseizer, electron microscope, and Western blot. The patients’ medical records were collected and analyzed. The expression level of exosomal miR-146a was evaluated in DLBCL patients and healthy donors using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The −ΔCt values of miR-146a were compared among responsive patients (n = 17), refractory patients (n = 16), patients receiving R-CHOP therapy (n = 15), and healthy donors (n = 6).

Results:

The presence and size of plasma-derived exosomes were confirmed. Our findings did not show any significant difference in the expression level of exosomal miR-146a between DLBCL patients and healthy donors (P = 0.48). As well, the clinical and histopathological parameters were not correlated with the expression level of exosomal miR-146a or plasma miR-146a. The expression level of plasma miR-146 was lower than the expression level of exosomal miR-146 (P = 0.01).

Conclusion:

Exosomal miR-146a might be useful as a promising “liquid biopsy” biomarker in predicting treatment response and relapse risk; however, we could not find significant differences due to small sample size.

Keywords: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, exosomes, miR-146a

INTRODUCTION

The diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of B-cell lymphoma in adults with an increasing prevalence among the different age groups in both genders. The disease exhibits a heterogeneity in gene expression profiles and clinical outcomes.[1,2] It can be classified into two molecular subgroups that are histologically indistinguishable (the germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) subgroup and the activated B-cell-like subgroup or [non-GCB]). These subgroups are different in pathogenesis, prognosis, and response to treatment.[3,4] The International Prognostic Index (IPI) has been the basis for determining prognosis among DLBCL patients. The IPI could identify the high-risk patients. The IPI is based on the five clinical characteristics including age, serum lactate dehydrogenase (sLDH), the number of extranodal sites, stage, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.[5] The LDH level increases significantly in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Therefore, elevated LDH level establishes the prognostic significance for both indolent and aggressive lymphomas at the time of diagnosis. The statistical analysis shows that patients with low LDH level have longer survival rate than the patients with high LDH level. High LDH level at the time of lymphoma diagnosis reveals increased tumor bulk.[6,7,8] In addition to the IPI, it is necessary to explore new prognostic tools such as miRNAs to improve the model's discrimination. The R-CHOP, a DLBCL treatment regimen, consists of rituximab, and cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovine and prednisone. However, patients with DLBCL have variable responses to therapy with R-CHOP. Approximately, one-third of DLBCL patients experience a relapse and even develop resistant to treatment.[9,10,11]

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small endogenous molecules that regulate the expression of genes in the posttranscriptional level by binding to the mRNA target. Many microRNAs such as miR-146a contribute to complex molecular mechanisms involved in controlling cell growth, differentiation, and survival. The changes in miRNAs levels might lead to cancer development or cancer progression. Therefore, miRNAs are considered as targets for the new treatments or suitable research candidates.[12,13]

Recent studies have shown that miR-146a is the modulator of innate and acquired immune responses.[14,15] miR-146a expression levels are associated with a wide range of nonhematologic and hematologic malignancies. In addition to the expression, level of miR-146a is not coincident among hematopoietic malignancies.[16,17,18]

Some studies show that miR-146a functions as a tumor suppressor having strong prognostic in natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma. As well, the low miR-146a expression is significantly associated with resistance to chemotherapy in patients with NK/T lymphoma. On the other hand, other studies indicate that the expression level of miR-146a is the difference between lymph nodes and the tissue of patients with DLBCL. They suggest that miR-146a could be a potential diagnostic tool in patients with DLBCL.[15,19,20,21,22]

Another study shows that miR-146b has an inhibitory effect on DLBCL cell proliferation. Therefore, the low miR-146b expression may be a useful biomarker to predict response to the CHOP regimen in patients with DLBCLs.[23]

Recently, it has been revealed that many types of cells release microvesicles in biological fluids, such as urine, serum, or breast milk. The microvesicles contribute to physiological and pathological processes either locally or remotely.[24] Exosomes (30–150 nm) are active biological nanovesicles that participate in a wide range of biological functions including intercellular communication, delivery of protein and genetic materials (miRNAs, RNA, and DNA), immune stimulation or immune suppression, tumor escape from the immune system, and the relationship between tumor cells.[25,26]

The blood collection is less invasive than bone marrow aspiration. Therefore, analysis of circulating miRNAs (exosomal miRNAs and free circulating miRNA) in the peripheral blood circulation can be the indicator for the diagnosis, prognosis, frequent follow-up, and relapse.[27] The exosomal miRNAs are secreted by an active process, while free circulating miRNA is generated by cell death (apoptosis or necrosis). Thus, exosomal miRNAs seem to be the more useful biomarker than free circulating miRNA.[28]

We isolated and confirmed pure exosomal fractions from plasma specimens. As well, we compared the expression level of miR-146a in plasma-derived exosomes of responsive or refractory patients with DLBCL, patients receiving R-CHOP, and healthy donors. In fact, the difference in the expression level of exosomal miR-146a among responsive or refractory patients with DLBCL and DLBCL patients receiving R-CHOP therapy might be useful to monitor treatment response or prediction of relapse in the future. In addition, we examined the association of exosomal miR-146a level with some clinical and histopathological features of the patients with DLBCL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Patients were consecutively selected from the Cancer Referral Centers in Isfahan, Iran. Plasma samples were obtained from patients with DLBCL and healthy donors. Clinical and laboratory data were obtained from medical records and included demographic data, presence of B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss), hematological and biochemical parameters (blood cell counts, hemoglobin/hematocrit, and sLDH), number of extranodal involved sites, palpable splenomegaly or hepatomegaly and Stage, the IPI and response to treatment. The DLBCL patients were classified into three groups based on R-CHOP therapy: patients receiving R-CHOP therapy were receiving 4 or 5 cycles of R-CHOP therapy (n = 15); The responsive patients who have achieved complete remission (CR) after 6–12 months of R-CHOP therapy (responsive patient, n = 17); and the refractory patients who had failed to 6 cycles of first-line treatment (R-CHOP) (n = 16). The responsive patients and refractory patients did not receive any chemotherapy during the sampling period. Then, the three patient groups were compared with healthy donors (n = 6). A written informed consent was taken from all participants. This study was approved by the Applied Physiology Research Center of Isfahan University Of Medical Sciences (the registration number: 295220). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients included in the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and healthy donors

| Characteristic | Responsive patients | Refractory patients | Patients receiving RCHOP | Healthy donors | P value (Chi-Square test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age=> P=0.36 | 49.59±15.48 | 46.3±11.07 | 48.25±9.56 | 38.33±4.45 | |

| n | 17 | 16 | 15 | 6 | |

| Sex=> P=0.43 | |||||

| Female | 7 (41.2) | 11 (68.8) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (50) | |

| Male | 10 (58.8) | 5 (31.3) | 10 (66.7) | 3 (50) | |

| LDH=> P=0.001 | |||||

| High | 4 (23.53) | 10 (62.5) | 5 (26.66) | χ2 | |

| IPI=> P=0.003 | 0-2 | 3-5 | 0-2 |

n=Number of people; LDH=Lactate dehydrogenase; IPI=International Prognostic Index; SD=Standard deviation; RCHOP = Rituximab, and cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovine and prednisone

Preparation of plasma samples and exosome isolation from plasma

Blood was drawn into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-containing tubes (5 ml). Plasma was isolated using centrifugation at 300 g for 10 min and further spun down at 2000 g for 20 min to remove dead cells and cell debris. Then, plasma was harvested, immediately aliquoted, and banked in −80°C until future use.

Plasma was centrifuged for 20 min at 2000 ×g, 4°C. The resulting supernatant was further centrifuged at 16000 ×g, 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. Then, exosomes were isolated using the ExoSpin Exosome Purification Kit (Cell Guidance Systems, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, the exosomes were stored at −80°C.

Transmission electron microscopy

The exosomal fractions were investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The exosomal fraction fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde was loaded on formvar/carbon-coated copper mesh grids. Then, grids were stained with uranyl acetate as a contrasting agent. Finally, samples were imaged using an FEI/Philips TEM 208S microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at an accelerating voltage of 100 KV.

Size determination

Size of exosomes was measured by a Zetasizer (Malvern Zen 3600 Instruments, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were diluted 1:50 in phosphate-buffered saline.

Analysis of plasma exosome-associated protein

Dot blot

Dot blot was used to detect exosomal marker (CD63, the transmembrane tetraspanin proteins) in the fraction containing lysed exosomes. The exosomal fractions were dropped into nitrocellulose (NC) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and washed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween-20 buffer and probed with anti-CD63 antibodies (rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG], System Biosciences, California). In the end, membranes were incubated with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (goat antirabbit HRP IgG, System Biosciences, California). The blot was developed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate.

Western blot

The exosomal fraction was lysed with 1× radioimmuno precipitation assay (RIPA; CMG, Iran) containing protease inhibitor (SIGMAFAST ™, USA) on ice. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method. Lysed exosomes were separated by electrophoresis in a 12% acrylamide sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel and then were transferred to NC membrane (BioRad, Hercules, and CA). The exosomal marker was visualized using primary antibodies (anti-CD63 antibody [rabbit IgG, System Biosciences, California] and anti-Histone H3 as a negative control [rabbit polyclonal, Bio-Legend, San Diego, CA]) and secondary antibody (goat antirabbit HRP IgG, System Biosciences, California). The blots stained with DAB as the chromogenic substrate in colorimetric detection.

Extraction of total RNA from plasma/plasma-derived exosomes and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from plasma and plasma-derived exosomes of DLBCL patients using a miRCURY™ Exosome Isolation Kit (Exiqon, Denmark), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was measured using a Nanodrop (ACTGene ASP-3700, USA) instrument. The quality of total RNA was confirmed by the 28S/18S rRNA ratio after running samples on 2% agarose gel. All steps performed under RNase-free conditions. cDNA was synthesized using the Universal cDNA Synthesis Kit II, 8–64 rxns (Exiqon, Denmark). The RNA samples were adjusted to 5 ng/μl per cDNA reaction and incubated for 60 min at 42°C followed by heat inactivation of the reverse transcriptase for 5 min at 95°C. Immediately cool to 4°C. If the RNA samples were not used immediately, they were stored at −80°C. The cDNA was diluted 1:4 with RNase-free water before quantification by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Real-time quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

RT-PCR was performed by the 2X RT-PCR Master Mix (BioFACT™, High ROX, Korea) with predesigned primers (LNA™ Primer mix, Exiqon, Denmark) for hsa-miR-146a, RNU5G (reference gene for plasma), and miR-103 (reference gene for exosomes). The RT-PCR reactions were carried out using a StepOnePlus™ quantitative RT-PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA, 48-well plates) under the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, and annealing and extension at 60°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s. The specificity and identity of the PCR products were verified by melting curve analysis after the last amplification cycle. To ensure the reproducibility and fidelity of the results, all samples were run in duplicate. The threshold cycle determination was generated automatically by the StepOnePlus™ quantitative RT-PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA, 48-well plates). The ΔCt was calculated by subtracting the Ct of the target gene (miR-146a) from the Ct of reference gene (RNU5G (plasma) or miR-103 (exosome)). Finally, ΔCt means were compared between the groups.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using software IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (Armonk, New York City, U.S.A) and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk normality test, P > 0.05). Therefore, we used the Chi-square, unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test, and analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) to compare groups. The values of <0.05 (P < 0.05) were considered to be statistically significant. The bivariate analysis was used to find out if there is a correlation between the exosomal miR-146 level and clinical and histopathological parameters.

RESULTS

A cross-sectional study was conducted including 48 patients with DLBCL. The median age of all patients was 54 years (range: 30–69 years). Most of the patients with non-GCB DLBCL were enrolled in the current study. The patients’ demographic characteristics were presented in Table 1. Immunohistochemical markers (CD10, BCL6, or BCL2) are commonly deregulated in DLBCL patients. These markers and clinical and histopathological parameters such as the IPI score and LDH level have the prognostic impact in the disease.[29] Therefore, we investigated the correlation between the expression level of miR-146 with IPI score and LDH level. The expression level of miR-146 was not correlated with the immunohistochemical makers and clinical and histopathological parameters. The DLBCL patients were divided into two groups according to IPI scores: low-risk group (0–2) or high-risk group (3–5). Refractory patients had high-risk disease according to the IPI score.

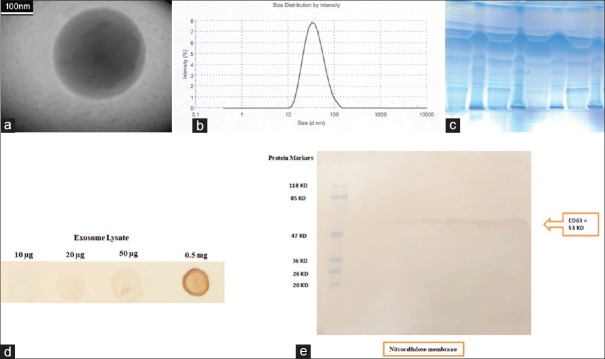

Characteristics of plasma-derived exosomes

The exosome-enriched fractions were prepared using ExoSpin Kit. Scanning electron microscopic examination of exosomal fractions showed spherical structures with the different sizes between 50 and 150 nm [Figure 1a]. The size measurement was conducted using a Zetasizer and the Z-average size of exosome was 48.34 nm [Figure 1b]. Furthermore, dot blot [Figure 1d] and Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of CD63 at the exosomes [Figure 1c and e].

Figure 1.

Confirmation of the fractions containing exosomes. (a) transmission electron microscopy image of exosome shows spherical morphology. Scale 100 nm. (b) Size distribution analysis of exosomes by Malvern Zetasizer. The particle-size distribution revealed that the average particle size was 48.34 nm. (c) Separation of exosomal proteins on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Fifty micrograms of exosomes lysate were run on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained by Coomassie Blue. CD63 On exosomes were confirmed by (d) Dot blot and (e) Western blot. The presence of canonical exosome protein (CD63) demonstrated a pure exosome preparation. The left panel shows the molecular weight markers

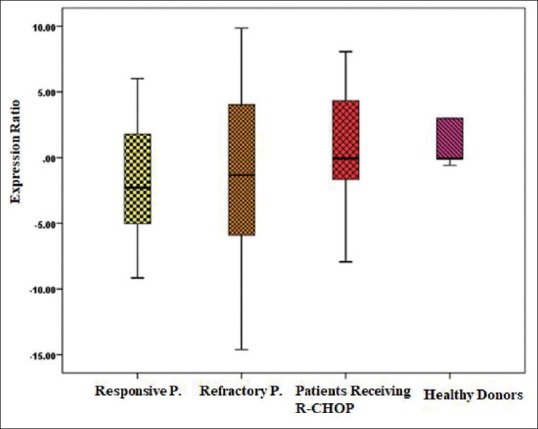

The expression level of miR-146 in plasma-derived exosomes and plasma

Total RNA was extracted from plasma and plasma-derived exosomes. The RNA yield from each sample ranged from 5 to 15 ng (Nanodrop instrument). The Ct value was above 33 cycles and considered as the threshold for reliable detection of miRNAs. There was no significant difference in the expression level of exosomal miR-146 between the refractory patients compared to responsive patients and patients receiving R-CHOP (P = 0.48, ANOVA test). Data have been shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. As well, the expression level of exosomal miR-146a was not significantly upregulated in DLBCL patients relative to the healthy donors (P = 0.3, t-test).

Table 2.

Comparison of the expression level of exosomal miR-146 between three groups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients and healthy donors

| Groups | −ΔCT (mean±SD) | P (ANOVA test) |

|---|---|---|

| Responsive patients | 1.9±4.5 | 0.48 |

| Refractory patients | 1.2±7.07 | |

| Patients receiving R-CHOP | 0.14±4.92 | |

| Healthy donors | −0.86±1.66 |

Relative exosomal miR-146 expression was evaluated in responsive patients, refractory/relapsed patients, patients receiving R-CHOP and also healthy donors. CT=Threshold cycle; R-CHOP=Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovine and prednisone; SD=Standard deviation; ANOVA=Analysis of variance

Figure 2.

Box plot diagrams show the expression levels of hsa-miR-146a in the plasma-derived exosomes of responsive DLBCL patients (n=17), refractory DLBCL patients (n=16), the patients receiving R- CHOP (n=15) and healthy donors (n=6). Expression levels of selected exosomal has-miR-146a were normalized to hsa-miR-103. The line within the boxes indicates the median expression level. There was no significant difference in groups (P = 0.48, ANOVA test)

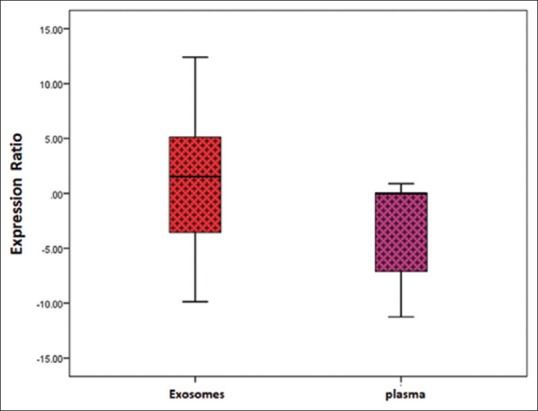

Furthermore, we addressed the question if there was a potential benefit in using exosomal fraction over whole plasma to detect circulating miR-146. Therefore, we collected plasma samples from 22 patients with DLBCL to compare the expression level of exosomal miR-146 relative to the expression level of plasma miR-146. As shown in Figure 3, the expression level of exosomal miR-146 was higher than the expression level of plasma miR-146 (P = 0.01, t-test).

Figure 3.

Comparison of expression level of miR-146 in the plasma and plasma-derived exosomes of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. RNU5G and miR-103 were used as the internal reference to normalize the threshold cycle value of miR-146 in plasma and plasma-derived exosomes, respectively. The results show the distribution of level of miR-146 in plasma relative to exosomes by Boxplot. The expression level of plasma miR-146 was lower than the expression level of exosomal miR-146. The expression level of miR-146 in exosomes was more than plasma (*P=0.01, t-test)

DISCUSSION

miRNA is considered as an important biomarker for the prognosis, prediction of treatment outcomes, and relapse-free survival, especially in hematological malignancies. miRNA is present in all biological fluids such as plasma. They are circulating freely or are encapsulated in exosomes.[30]

In the current study, exosomes were isolated from plasma of responsive or refractory patients with DLBCL, patients receiving R-CHOP, and healthy donors. We showed exosomes were spherical nanovesicles, ranging from 30 to 150 nm in diameter. As well, the protein composition of plasma vesicles was in agreement with their exosomal origin.

Some studies have shown that the expression levels of miR-146a and miR-146b were upregulated in the DLBCL patients compared to the patients with Burkitt lymphoma.[20,31,32] Zhuang et al. showed that miR-146a level was significantly higher in patients with DLBCL than healthy donors. They suggested that miR-146a could play an important role in the pathogenesis of DLBCL disease.[33] Caramuta et al. compared directly the de novo and transformed DLBCL using significance analysis of microarrays analysis. The analysis showed increased expression of miR-146a in de novo compared with transformed DLBCL. Results from the microarray and RT-quantitative PCR indicated that miR-146a could discriminate GCB from non-GCB cases. The founding revealed the significant overexpression of miR-146a in the non-GCB group.[34] Zhong et al. investigated the expression level of miR-146a in the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies from DLBCL patients and demonstrated that the low expression of miR-146a could be associated with CR rate and overall response rate.[35] Contradictory, our results showed that there was no significant difference in exosomal miR-146a expression among refractory patients with DLBCL, responsive patients with DLBCL, and DLBCL patients receiving R-CHOP. As well, we did not observe the significant difference in exosomal miR-146a expression between patients with DLBCL and healthy donors. This is likely to be due to the small samples size that we could not find any significant differences between our groups.

In contrast to our study, Zhong et al. demonstrated that the expression level of miR-146a was associated with LDH level and IPI in the de novo DLBCL patients. However, we could not find any significant correlation between the expression level of miR-146a and both LDH level and IPI in the DLBCL patients.[35]

Gallo et al. compared miRNAs levels in serum and serum-derived exosomes. They showed that the exosomal fraction increases the sensitivity of miRNA detection in biological fluids, and these differences may be much higher for some miRNAs.[36] Our results showed that the expression level of exosomal miR-146a was higher than the expression level of plasma miR-146a. miR-146a seems to have accumulated in the exosomes. However, analysis of miRNA expression as validated biomarkers of the disease strongly depends on the size of cohorts/sets of samples analyzed.

CONCLUSION

It appears that morphologically intact exosomes can be successfully purified from plasma.

The measurement of exosomal miRNAs obtained from biological fluids constitutes a noninvasive approach for the diagnosis, prediction of response to treatment and risk to relapse, and also prognosis of cancer.

The exosome-encapsulated microRNAs seem to have less variation than circulating miRNA. Therefore, the evaluation of exosomal microRNAs instead of plasma microRNAs could reduce the probability of false-negative or positive results.[36]

Our data suggest that exosomal miR-146a might be diagnostic tools and prognostic indicators for DLBCL patients. However, we could not find any significant differences. Additional studies, including the evaluation of miR-146a expression in a large number of DLBCL patients, are required to clarify the role of miR-146a as a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Applied Physiology Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank nurses and personnel of the Alzahra Hospital and Sayed Al-Shohada Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilly H, Dreyling M ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v172–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elias AD. Advances in the diagnosis and management of sarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol. 1990;2:474–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz G, Staudt LM. Aggressive lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1417–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0807082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, Gordon LI, Lacasce AS, Crosby-Thompson A, et al. An enhanced international prognostic index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood. 2014;123:837–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.William BM, Bongu NR, Bast M, Bociek RG, Bierman PJ, Vose JM, et al. The utility of lactate dehydrogenase in the follow up of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2013;35:189–91. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20130055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolaides C, Fountzilas G, Zoumbos N, Skarlos D, Kosmidis P, Pectasides D, et al. Diffuse large cell lymphomas: Identification of prognostic factors and validation of the international non-Hodgkin's lymphoma prognostic index. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Oncology. 1998;55:405–15. doi: 10.1159/000011886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraris AM, Giuntini P, Gaetani GF. Serum lactic dehydrogenase as a prognostic tool for non-hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 1979;54:928–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manches O, Lui G, Chaperot L, Gressin R, Molens JP, Jacob MC, et al. In vitro mechanisms of action of rituximab on primary non-hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2003;101:949–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Klasa R, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in british columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5027–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedberg JW. New strategies in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Translating findings from gene expression analyses into clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6112–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazan-Mamczarz K, Gartenhaus RB. Role of microRNA deregulation in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) Leuk Res. 2013;37:1420–8. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budhu A, Ji J, Wang XW. The clinical potential of microRNAs. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labbaye C, Testa U. The emerging role of MIR-146A in the control of hematopoiesis, immune function and cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik JH, Jang JY, Jeon YK, Kim WY, Kim TM, Heo DS, et al. MicroRNA-146a downregulates NFκB activity via targeting TRAF6 and functions as a tumor suppressor having strong prognostic implications in NK/T cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4761–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Luo XQ, Zhang P, Huang LB, Zheng YS, Wu J, et al. MicroRNA patterns associated with clinical prognostic parameters and CNS relapse prediction in pediatric acute leukemia. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visone R, Rassenti LZ, Veronese A, Taccioli C, Costinean S, Aguda BD, et al. Karyotype-specific microRNA signature in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3872–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Li Z, He C, Wang D, Yuan X, Chen J, et al. MicroRNAs expression signatures are associated with lineage and survival in acute leukemias. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;44:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, Di Leva G, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, et al. A microRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1793–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrie CH, Soneji S, Marafioti T, Cooper CD, Palazzo S, Paterson JC, et al. MicroRNA expression distinguishes between germinal center B cell-like and activated B cell-like subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1156–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roldo C, Missiaglia E, Hagan JP, Falconi M, Capelli P, Bersani S, et al. MicroRNA expression abnormalities in pancreatic endocrine and acinar tumors are associated with distinctive pathologic features and clinical behavior. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4677–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu PY, Zhang XD, Zhu J, Guo XY, Wang JF. Low expression of microRNA-146b-5p and microRNA-320d predicts poor outcome of large B-cell lymphoma treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1664–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turturici G, Tinnirello R, Sconzo G, Geraci F. Extracellular membrane vesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication: Advantages and disadvantages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C621–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X, Yuan T, Tschannen M, Sun Z, Jacob H, Du M, et al. Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lugini L, Cecchetti S, Huber V, Luciani F, Macchia G, Spadaro F, et al. Immune surveillance properties of human NK cell-derived exosomes. J Immunol. 2012;189:2833–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revenfeld AL, Bæk R, Nielsen MH, Stensballe A, Varming K, Jørgensen M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of extracellular vesicles in peripheral blood. Clin Ther. 2014;36:830–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manier S, Liu CJ, Avet-Loiseau H, Park J, Shi J, Campigotto F, et al. Prognostic role of circulating exosomal miRNAs in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;129:2429–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradshaw G, Sutherland HG, Haupt LM, Griffiths LR. Dysregulated microRNA expression profiles and potential cellular, circulating and polymorphic biomarkers in non-hodgkin lymphoma. Genes (Basel) 2016;7 doi: 10.3390/genes7120130. pii: E130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Lisio L, Sánchez-Beato M, Gómez-López G, Rodríguez ME, Montes-Moreno S, Mollejo M, et al. MicroRNA signatures in B-cell lymphomas. Blood Cancer J. 2012;2:e57. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenze D, Leoncini L, Hummel M, Volinia S, Liu CG, Amato T, et al. The different epidemiologic subtypes of burkitt lymphoma share a homogenous micro RNA profile distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1869–76. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuang H, Shen J, Zheng Z, Luo X, Gao R, Zhuang X, et al. MicroRNA-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and the risk of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the chinese han population. Med Oncol. 2014;31:306. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0306-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caramuta S, Lee L, Ozata DM, Akçakaya P, Georgii-Hemming P, Xie H, et al. Role of microRNAs and microRNA machinery in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e152. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong H, Xu L, Zhong JH, Xiao F, Liu Q, Huang HH, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of miR-155 and miR-146a expression levels in formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded tissue of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:763–70. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallo A, Tandon M, Alevizos I, Illei GG. The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]