Abstract

Unlike oocytes of many other mammalian species, parthenogenetically activated hamster oocytes have not been reported to develop beyond the two-cell stage. This study investigated the in vitro development into blastocysts of parthenogenetic embryos of Golden Syrian hamsters. We observed that hamster oocytes could easily be artificially activated (AA) by treatment with ionomycin plus 6-dimethylaminopurine + cycloheximide + cytochalasin B as assessed by embryo cleavage in HECM-9 (63.15%) or HECM-10 (63.82%). None of the cleaved embryos developed beyond the two-cell stage when cultured in either of the two media. However, some of the embryos overcame the two-cell block and developed to the blastocyst stage (26.45%) when they were first cultured in HECM-10 for 24 hours and then in HECM-9 (serial culture media HECM-10-9) for 72 hours. Blastocyst development was further significantly (66.2%) improved when embryos were cultured in HECM-10 supplemented with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 24 hours, then in HECM-9 supplemented with glucose for 72 hours (serial culture media HECM-11a-b). Hamster oocytes activated with ionomycin, ethanol, or a combination of the two treatments would develop to the blastocyst stage in serial culture media HECM-11a-b, whereas none of the spontaneously activated oocytes cleaved (0% vs. 86.93%, p < 0.05). DNA and microtubule configurations of spontaneously activated and AA oocytes were assessed by immunocytochemical staining and fluorescence microscopy. The results indicate that serial culture and the method of activation are critical for overcoming the in vitro developmental block of hamster parthenogenetic embryos. This study is the first to report blastocyst development from parthenogenetically activated hamster oocytes.

Keywords: : hamster oocytes, parthenogenetic activation, blastocyst, serial cultural media

Introduction

Parthenogenesis has been used as a model system to study biochemical and morphological events during early embryonic development (Collas et al., 1993). Artificial activation of oocytes is a critical step for somatic cell nuclear transfer, haploid and tetraploid embryo production (Lin et al., 2011), and generation of parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells (Ragina et al., 2012) and parthenogenetic animals (Chen et al., 2009) used in biomedical and reproductive research. Hamster oocytes have been used to study the processes involved in in vitro fertilization (Tsunoda and Chang, 1976) and as a test for human sperm fertility (Barros et al., 1978). But unlike oocytes of many other animal species, hamster oocytes have not yet been reported to develop to the blastocyst stage after parthenogenetic activation.

Hamster oocytes are very sensitive to in vitro culture conditions and can be easily spontaneously activated in vitro (He et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2002). Tateno and Kamiguchi (1997) reported that several chemical agents, such as ethanol, calcium ionophore A23187, cycloheximide (CHX), strontium, phorbol ester, and 6-dimethylaminopurine (6-DMAP), all of which stimulate mouse oocytes, also activate hamster oocytes. However, embryonic development has not been reported to proceed beyond the two-cell stage in artificially activated (AA) hamster oocytes (Jiang et al., 2015; Tateno and Kamiguchi, 1997). There have been no follow-up studies since the reports already cited. This led us to determine whether the spontaneous activation property is unique to hamster oocytes or whether it was simply induced by in vitro incubation within certain culture environments.

Most mammalian oocytes can be parthenogenetically activated with an induction method that causes a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ and subsequent Ca2+ oscillations, mimicking the events during normal fertilization (Swann and Ozil, 1994). Several chemicals such as Ca2+ ionophore, ethanol, strontium chloride, phorbol ester, and thimerosal have been shown to induce oocyte activation (Machaty and Prather, 1998). Ionomycin is a potent Ca2+ ionophore, which mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ by depletion of Ca2+ stores used for oocyte activation in nuclear transfer protocols (Cibelli et al., 1998; Meng et al., 2011). Exposure of matured bovine oocytes to 7% ethanol for 5–7 minutes will usually induce activation and pronuclear formation (Presicce and Yang, 1994) by promoting the formation of IP3 and the influx of extracellular Ca2+.

Electrical stimulation is often used as an alternative method to chemical activation to induce Ca2+ influx through the formation of pores in the plasma membrane (Zimmermann et al., 1985). To activate mature oocytes, they must be induced to trigger resumption of meiosis, chromatin decondensation, and transition to interphase. Maturation promoting factor (MPF) is essential for meiotic arrest at metaphase II (Nurse, 1990). Inhibitors of protein synthesis such as CHX and 6-DMAP induce oocyte activation in mice (Moses and Kline, 1995) and humans (Balakier and Casper, 1993) by decreasing the MPF level in metaphase oocytes.

Mammalian embryonic development in vitro is often arrested at the embryo genome activation stage due to inadequate culture conditions, a phenomenon commonly referred to as a developmental block. Hypoxanthine in Biggers-Whitten-Whittingham (BWW) medium causes a two-cell block in CD-1 mice, which can be partially (40%) overcome by adding the chelating agent ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Loutradis et al., 1987). Culturing mouse embryos in Chatot-Ziomek-Bavister (CZB) medium, modified from BMOC-2 by adding glutamine and EDTA and deleting glucose, will overcome the two-cell block, although blastocyst development will not occur unless embryos are exposed to glucose at the three- to four-cell stage (Chatot et al., 1989, 1990, 1994).

Fertilized hamster one-cell embryos are similarly blocked at the two-cell stage in culture (Schini and Bavister, 1988a). The removal of glucose from the medium will partially eliminate the two-cell block and development will proceed to the eight-cell or morula stage in vitro (Schini and Bavister, 1988b). However, glucose is required for the development of hamster two-cell embryos to the blastocyst stage of development when 10 mM lactate is added to the medium (McKiernan et al., 1991). Although fertilized one-cell hamster embryos can develop to the blastocyst stage in vitro (Bavister and Arlotto, 1990; McKiernan and Bavister, 1990, 2000; McKiernan et al., 1995), post cleavage development does not occur in parthenogenetic hamster embryos. These studies suggest that parthenogenetic hamster embryos require unique in vitro conditions to support development.

In this study, we successfully cultured hamster parthenogenetic embryos to the blastocyst stage with newly formulated serial cultural media HECM-11a-b or HECM-10-9. We compared spontaneous activation profiles between hamster oocytes and bovine oocytes, investigated in vitro development of parthenogenetic hamster embryos produced by activation with ionomycin, ethanol, and the protein synthesis inhibitors 6-DMAP and CHX treatments. We also compared the developmental competence of spontaneously activated and AA hamster oocytes.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and animals

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Golden Syrian hamsters used for oocyte collection were bred in an air-conditioned room with a 14 L:10 D cycle (light from 6:00 am) using founder animals purchased from Charles River (LVG Golden Syrian Hamster, Strain Code: 049). The experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Research Center at the Utah State University and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Utah State University (IACUC Protocol: 2384).

Oocyte collection

Eight- to 12-week-old female golden Syrian hamsters were superovulated by an i.p. injection of 15–25 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin the morning of the day of postestrus discharge (day 1 of the estrous cycle), followed by an injection of the same dose of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 60 hours later (McKiernan and Bavister, 2000). The hamsters were euthanized 14–14.5 hours post-hCG injection, and the oviductal ampullae were collected and torn open to release the cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs). The oocytes were denuded of cumulus cells by light pipetting after incubation in 199 TE (199 medium containing 5 mM taurene and 25 μm EDTA) (Haigo et al., 2004) with 0.1% hyaluronidase for <1 minute.

Collection and maturation of bovine oocytes were carried out as described previously (Meng et al., 2011). In brief, bovine COCs were aspirated from 3- to 8-mm diameter follicles of ovaries obtained from a local abattoir. The COCs were matured in TCM 199 with Earle's salts, l-glutamine, and sodium bicarbonate (Gibco, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 25 μg/mL gentamycin, 0.01 U/mL FSH (NIH-FSH-S17), 0.01 U/mL LH (USDA-bLH-6) in 4-well plates with 0.5 mL medium and 30–50 oocytes per well at 38.5°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air for 22 hours. Cumulus cells were removed by pipetting COCs in Hepes-buffered synthetic oviductal fluid (SOF) medium containing 0.1% hyaluronidase. Only oocytes with first polar bodies were used in the experiments.

Embryo culture media

Parthenogenetic hamster embryos were cultured in one of the following media: (1) HECM-9 (McKiernan and Bavister, 1998, 2000) for 96 hours; (2) HECM-10 (modified from HECM-9 with 2.0 mM magnesium and 0.5 mM calcium) (Lane et al., 1998) for 96 hours; (3) serial culture media HECM-10-9 (i.e., embryos were first cultured in medium with a lower concentration of Ca2+ and a higher concentration of Mg2+ (HECM-10) for 24 hours, then in medium with regular concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HECM-9) for 72 hours; and (4) serial culture media HECM-11a-b (i.e., embryos were cultured in HECM-11a for 24 hours, then HECM-11b for 72 hours).

The HECM-11a-b serial culture media were developed in our laboratory. HECM-11a is HECM-10 supplemented with 25 μM EDTA and 5 mg/mL human serum albumin (HSA) instead of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA); HECM-11b is HECM-9 supplemented with 2 mM glucose and 5 mg/mL HSA. A group of 20–40 embryos were cultured in a 35 μL droplet of one of the mentioned media at 37.5°C in 10% CO2, 5% O2, 85% N2 under 100% humidified conditions.

Oocyte activation

The hamster oocyte artificial activation methods were modified from our previous report (Meng et al., 2011). A group of 20–40 oocytes were incubated in 199 TE supplemented with 5 μM ionomycin (I), or 7% ethanol (E), or 2.5 μM ionomycin and 3.5% ethanol (I+E) for 5 min, followed by incubation in a 35 μL drop of HECM-11a with 1 mM 6-DMAP, 5 μg/mL CHX, and 5 μg/mL cytochalasin B (CB) for 3 hours at 37°C in 10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2 under 100% humidified conditions.

Then the oocytes were subjected to embryo culture or immunocytochemical staining. To examine their spontaneous activation profiles, hamster oocytes were released from COCs and directly incubated in embryo culture medium HECM-11a at 37°C in 10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2 for 3 or 6 hours. Bovine oocytes were released from COCs and directly incubated in embryo culture medium SOFaa (SOF with amino acids) at 38.5°C in 5% CO2 for 3 or 6 hours. Then the oocytes were subjected to immunocytochemical staining.

Immunocytochemical staining of oocytes

Oocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mg/mL PVA for 10 min at room temperature then kept in PBS containing 1 mg/mL PVA overnight at 4°C. The oocytes were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in PBS for 10 minutes. After washing twice with PBS containing 0.01% Triton X-100, the oocytes were blocked in PBS containing 150 mM glycine, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature.

The oocytes were then incubated in fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:80) in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C. DNA was stained with 20 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 for 20 minutes at room temperature. Oocytes were mounted on slides in 50% glycerol in PBS and then examined under a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Optical, Inc., Chester, VA). Images were captured by a digital camera and analyzed with the Axio Vision LE Program (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Experimental design

As shown in Figure 1, we designed the following experiments: (1) Comparison of in vitro spontaneous activation of hamster and bovine oocytes. Oocytes were fixed after 0, 3, and 6 hours incubation at 37°C after their release from COCs using hyaluronidase. The parthenogenetic activation status of oocytes was determined by observation of DNA distribution and microtubule configuration after immunocytochemical staining. Activated oocytes were observed at anaphase II or telophase II, with second polar bodies extruded or with a pronucleus. Oocytes were considered inactivated if they remained at metaphase II.

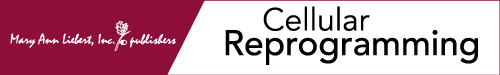

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of experimental design.

(2) Comparison of in vitro development of parthenogenetic embryos in different culture media. Oocytes were activated with 5 μM ionomycin for 5 minutes, followed by treatment with 1 mM 6-DMAP, 5 μg/mL CHX, and 5 μg/mL CB in HECM-11a for 3 hours. Parthenogenetic embryos were then cultured in one of the following media: (i) HECM-9, (ii) HECM-10, (iii) serial culture media HECM-10-9, and (iv) serial culture media HECM-11a-b for 96 hours. The cleavage and blastocyst rates were assessed at 24 and 96 hours of culture.

(3) Comparison of in vitro development between parthenogenetic embryos produced with different activation methods. The oocytes were activated with one of the following treatments: (i) 5 μM ionomycin (I), (ii) 7% ethanol (E), or iii) 2.5 μM ionomycin and 3.5% ethanol (I+E) for 5 minutes, followed by treatment with 1 mM 6-DMAP, 5 μg/mL CHX, and 5 μg/mL CB in HECM-11a for 3 hours. The parthenogenetic embryos were cultured in serial culture media HECM-11a-b for 96 hours then cleavage and blastocyst rates were assessed.

(4) Comparison of in vitro development between artificially and spontaneously activated hamster oocytes. Oocytes were divided into two groups after release from COCs. One group was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours to induce spontaneous activation (SA). The other group was AA with 5 μM ionomycin for 5 minutes followed by treatment with 1 mM 6-DMAP, 5 μg/mL CHX, and 5 μg/mL CB for 3 hours at 37°C. Both groups of oocytes were cultured in serial culture media HECM-11a-b for 96 hours then cleavage and blastocyst rates were assessed.

(5) Investigation of DNA and microtubule configurations in early stage artificially parthenogenetically activated hamster oocytes. Oocytes were AA with ionomycin treatment followed by incubation in 6-DMAP, CHX, and CB and then cultured in HECM-11a as already described. Six to 10 oocytes were fixed per group with 4% paraformaldehyde after 0–1.5 hours of culture at 45-minute intervals, and at 1.5-hour intervals 3–9 hours postactivation. DNA and microtubule status were assessed with epifluorescence microscopy after immunocytochemical staining as already described. All experiments were replicated three to four times.

Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test using SPSS statistical software (IBM, IL) was used to analyze the data. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of in vitro spontaneous activation between hamster and bovine oocytes

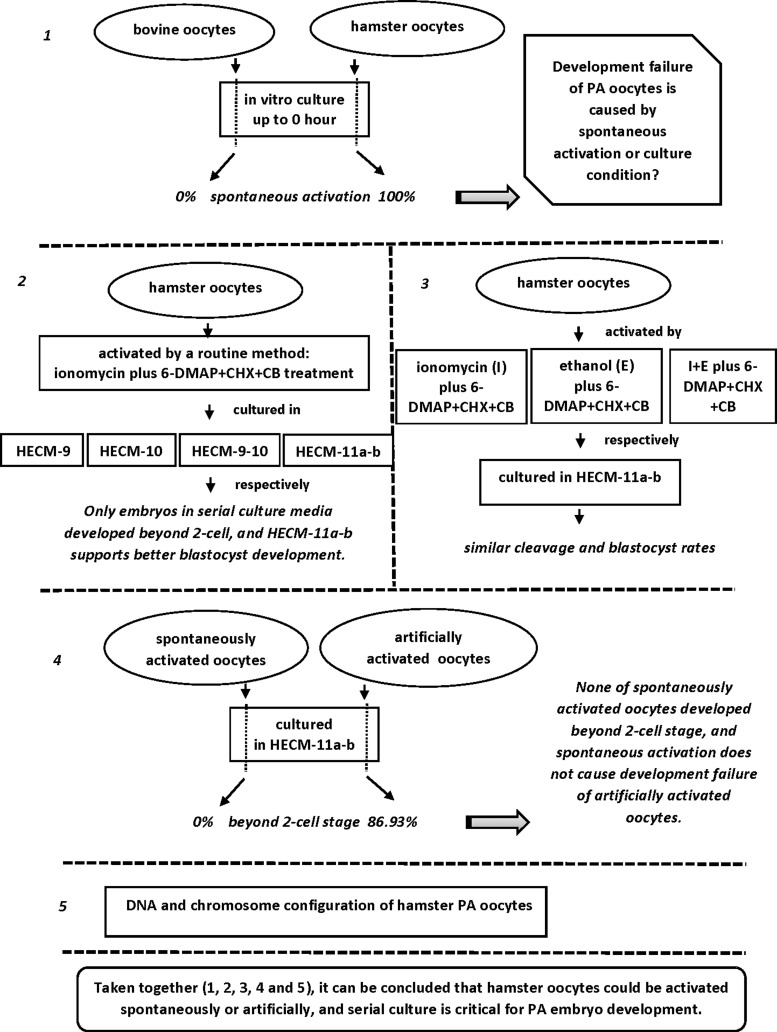

In this experiment, oocyte activation status was assessed by observation of DNA and spindle morphology. The results showed that all of the newly released hamster oocytes were at metaphase II. Fifty-nine percent of oocytes (n = 39) were spontaneously activated after 3 hours incubation, and all were activated by 6 hours (n = 42). Unlike hamster oocytes, none of the bovine oocytes activated spontaneously during the 6 hours incubation period (n = 22 + 35) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Representative figures of spontaneously activated hamster oocytes compared with those of bovine oocytes. After 3 hours incubation in vitro, 59.0% (n = 39) of hamster oocytes were spontaneously activated, and 100% (n = 42) of the oocytes were activated after 6 hours incubation. The figures show a spontaneously activated hamster oocytes at anaphase II (3 hours) and an oocyte at the pronuclear stage (6 hours). None of the mature bovine oocytes were spontaneously activated after either 3 (n = 22) or 6 hours (n = 35) incubation. Figures show two bovine metaphase II oocytes (3 and 6 hours).

Comparison of in vitro development of parthenogenetic embryos in different culture media

In this experiment, the developmental potential of parthenogenetic embryos cultured in different media was assessed. We had previously observed that hamster oocytes could be successfully activated using a method we routinely use to activate bovine oocytes (Meng et al., 2011). As shown in Table 1, the activated oocytes developed to, and then became arrested, at the two-cell stage when cultured in either HECM-9 (63.15%) or HECM-10 (63.82%). However, a few of the arrested embryos overcame the two-cell block and developed to the blastocyst stage when first cultured in HECM-9 with lower Ca2+ and higher Mg2+ concentrations (HECM-10) for 24 hours, then placed in medium with regular concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HECM-9). In vitro development significantly improved when embryos were cultured in the formulated serial culture media HECM-11a-b compared with HECM-10-9 (66.2% vs. 26.45%).

Table 1.

In Vitro Development of Hamster Parthenogenetic Embryos in Different Culture Media

| No. of embryos developed to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture medium | No. of oocytes | Two-cell stage (%) | Blastocyst (%) |

| HECM-10 | 95 | 60 (63.82 ± 3.93)a | 0a |

| HECM-9 | 108 | 72 (63.15 ± 4.92)a | 0a |

| HECM-10-9 | 102 | 67 (68.75 ± 4.62)a | 16 (26.45 ± 4.29)b |

| HECM11a-b | 90 | 61 (70.55 ± 4.64)a | 39 (66.20 ± 5.73)c |

All data are from four replicates. Values with different superscripts (a–c) in the same column differ significantly (p < 0.05).

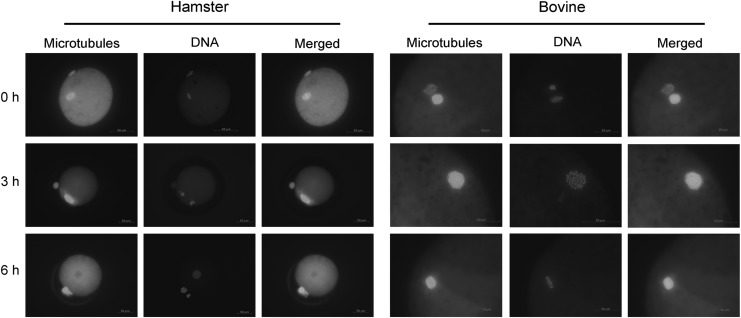

The in vitro development of parthenogenetic hamster embryos is very similar to that of fertilized embryos. HECM-11a-b supported embryo development to the hatched blastocyst stage. We observed that hamster blastocyst cavities shrank shortly after embryos hatched from the zona pellucida, which is unlike hatched blastocysts of bovine, sheep, goat, or rabbit where the cavities remain unchanged for days under in vitro culture conditions and the early or expanding blastocysts have distinct cavities (Fig. 3). Similarly, it was observed by Gonzales DS and Bavister that hamster blastocysts produced in vivo also have small or totally collapsed blastocele cavities (Gonzales and Bavister, 1995), suggesting that this is a unique physiological feature of hamster embryos.

FIG. 3.

Representative figures of blastocysts produced by artificial activation. Oocytes were activated by ionomycin plus 6-DMAP + CHX + CB treatments. Parthenogenetic embryos were incubated in serial culture media HECM-11a-b. Blastocysts were photographed under bright field (A) or UV light after DNA staining with Hoechst (B). (A) is a group of early or expanding blastocysts at 84 hours of in vitro culture. (B) represents the cell nuclei of a blastocyst. Details of the preparation are described in Materials and Methods section. CHX, cycloheximide; 6-DMAP, 6-dimethylaminopurine; CB, cytochalasin B.

Comparison of in vitro development between parthenogenetic hamster embryos produced with different activation protocols

As shown in Table 2, oocytes were treated with ionomycin (I), ethanol (E), or ionomycin plus ethanol (I+E) for 5 minutes, then they were incubated in medium HECM-11a supplemented with 6-DMAP+CHX+CB for 3 hours, and then their development was monitored. The results showed that ionomycin or ethanol, or the combination thereof, activated hamster oocytes and resulted in similar cleavage rates (74.0%, 88.13%, and 83.5%, respectively, p < 0.05). Blastocyst developmental rates were not different between the treatment groups (30.63%, 26.47%, 28.7%, respectively, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of In Vitro Development Between Parthenogenetic Embryos Produced by Different Activation Methods

| No. of embryos developed to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation method | No. of oocytes | Two-cell stage (%) | Blastocyst (%) |

| I | 65 | 47 (74.00 ± 10.30)a | 14 (30.63 ± 4.92)a |

| E | 66 | 59 (88.13 ± 9.21)a | 14 (26.47 ± 6.35)a |

| I + E | 89 | 77 (83.50 ± 4.97)a | 17 (28.70 ± 8.18)a |

All data are from three replicates. Values with same superscript (a) within each column denote no significant difference (p > 0.05).

I, ionomycin (treatment); E, ethanol; I+E, ionomycin + ethanol.

Comparison of in vitro development between artificially and spontaneously activated hamster oocytes

Experiment 1 demonstrated that hamster oocytes could be spontaneously activated. In this experiment we examined the developmental capacity of spontaneously activated hamster oocytes. Oocytes were cultured under the same conditions after being spontaneously activated or AA. Although 34.67% of AA oocytes developed to the blastocyst stage, none of the spontaneously activated (SA) oocytes cleaved (0% vs. 86.93%, p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of In Vitro Developmental Capacity Between Artificial and Spontaneously Activated Hamster Oocytes

| No. of embryos developed to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | No. of oocytes | Two-cell stage (%) | Blastocyst (%) |

| AA | 64 | 56 (86.93 ± 2.78)a | 19 (34.67 ± 8.30) |

| SA | 52 | 0b | N/A |

All data are from three replicates. Values with different superscripts (a and b) in the same column differ significantly (p < 0.05).

AA, artificial activation; SA, spontaneous activation.

Examination of DNA and microtubule assemblies in early stages of artificially parthenogenetically activated hamster oocytes

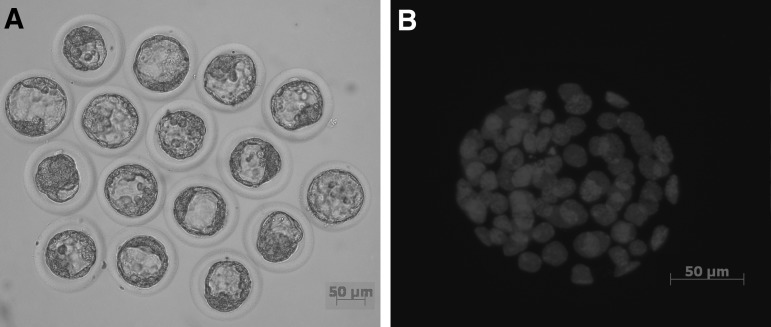

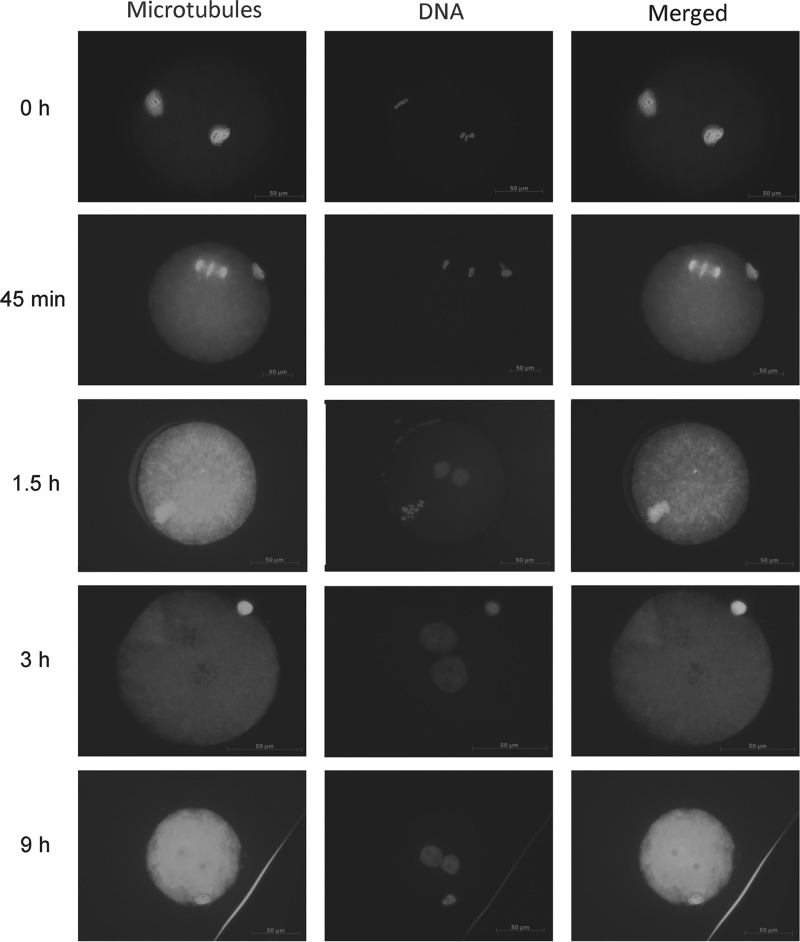

The structures were delineated with epifluorescence microscopy after immunocytochemical staining as already described. Figure 4 shows the major changes that occurred during activation. All oocytes were at metaphase II before activation with chromosomes condensed and aligned on the spindles (0 hours of activation). Shortly after activation, the oocytes entered into second meiosis and proceeded to anaphase II and telophase II, during which the chromatids were separated by movement of the microtubules followed by the decondensation of chromosomes. The microtubules then disappeared with the concurrent formation of two pronuclei. This sequential process occurred in most of the oocytes. The pronuclei remained in place for around 14 hours and then moved toward each other and merged.

FIG. 4.

Representative figures of the DNA and microtubule status in the early stages of artificially activated hamster oocytes. Before activation, a metaphase II stage oocyte has chromosomes with condensed DNA arranged on the spindle (0 hours of activation). At 45 minutes postactivation, oocytes are at anaphase of the second meiosis. The chromatids are pulled by microtubules to separate and move to opposite poles (45 minutes). As the activated oocytes progress, DNA is now becoming decondensed, microtubules disappear, and two pronuclei form (1.5, 3 hours). Then the two pronuclei move toward each other to form a diploid nucleus (9 hours).

Discussion

Successful activation of mammalian oocytes entails the resumption of meiotic division and subsequent embryonic development. Until this study, parthenogenetic hamster embryos had not been reported to develop beyond the two-cell stage, although hamster oocytes could be AA (Tateno and Kamiguchi, 1997). The failure of further development was attributed to artificially induced insurmountable barriers inherent in the activation procedure or by the limitations of the culture system. We investigated this problem by developing serial culture media that would support embryo development and then evaluated various activation methods. This approach resulted in parthenogenetic hamster embryos capable of developing into blastocysts.

Under in vivo conditions, mammalian embryos complete early development in a highly efficient manner within a dynamic maternal environment. As already described, hamster oocytes are very sensitive to changes in the prevailing environment. When we compared spontaneous activation profiles between hamster and bovine oocytes, we observed that bovine oocytes would not undergo spontaneous activation under in vitro experimental conditions, whereas hamster oocytes spontaneously activated within 6 hours of in vitro incubation. This is the first report of side-by-side comparisons of spontaneous activation profiles of oocytes between two different species. Hamster oocytes appear to be more sensitive to the in vitro environment than bovine oocytes. We were not able to control spontaneous activation under the conditions in this study.

The high spontaneous activation rate of hamster oocytes in this study is in agreement with other reports on hamster oocyte spontaneous activation (Jiang et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2002). Although hamster oocytes can easily be AA, parthenogenetic hamster embryos are very sensitive to culture conditions. Therefore, we investigated whether the developmental failure can be overcome by using a serial culture approach. In this study, we first cultured parthenogenetically activated hamster embryos in HECM9 or HECM10 (HECM9 with modified Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations) medium and found that embryos cleaved normally but their development was arrested at the two-cell stage.

To overcome the two-cell block, we changed from a single to serial cultural media. Because the maintenance and regulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis are critical for normal oocyte activation and early embryo development, we modified the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ and supplemented the regular HECM media with EDTA and glucose. By adjusting the magnesium and calcium concentrations in HCEM-9 from 0.5 and 2.0 mM to 2.0 and 1.0 mM, respectively, (hereafter referred to as HECM-10, as previously described by McKiernan and Bavister (2000), the intracellular calcium levels were closer to what is reported for in vivo development (Lane et al., 1998). HECM-10 alone, however, did not support development of parthenogenetic hamster embryos.

The metal ion chelator EDTA and glucose have important roles in overcoming the two-cell block in mouse embryos, and their effects are developmental stage-specific. EDTA has been shown to be particularly beneficial for overcoming the two-cell block (Dienhart and Downs, 1996; Gardner and Lane, 1996; Matsukawa et al., 2002; Nasr-Esfahani et al., 1992; Park et al., 2000). The reversal of hypoxanthine-induced arrest by cAMP-elevating agents is critically dependent on the presence of EDTA (Dienhart and Downs, 1996). The beneficial effect of EDTA is during the first 48 hours of culture, or before the eight-cell stage, but becomes inhibitory during the second 48 hours (Gardner and Lane, 1996; Park et al., 2000).

Deletion of glucose from culture media helps mouse embryos develop through the two-cell stage, but embryos cannot develop to the blastocyst stage unless they are exposed to glucose at the three- to four-cell stage (Chatot et al., 1989; Nasr-Esfahani et al., 1992). We supposed that parthenogenetic hamster embryos might also have different nutrient requirements in the early versus late two-cell stage.

Therefore, we used a serial system approach to culture parthenogenetic hamster embryos. Embryos were cultured in medium with lower Ca2+ and higher Mg2+ concentrations and EDTA (referred to as HECM-11a) for 24 hours, and then in medium with normal concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ and glucose (referred to as HECM-11b) for 72 hours. When the parthenogenetic hamster embryos were serially cultured in HECM10-9, the two-cell block was partially overcome. Blastocyst development was significantly improved when embryos were serially cultured in HECM-11a-b. These results support our hypothesis that parthenogenetic hamster embryos have different nutrient requirements at the early and late two-cell stages.

An earlier study indicated that hamster oocytes can be activated and undergo cleavage by using a combination of two chemical stimulators or protein synthesis inhibitors (Tateno and Kamiguchi, 1997). In that study it was reported that a combination of Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and CHX produced the highest cleavage rate, although development of the parthenogenetic embryos was not reported. The use of a Ca2+ stimulator along with an inhibitor of protein synthesis has been widely used for the activation of mouse, sheep, and cattle oocytes.

In this study, we activated hamster oocytes with a combined treatment of ionomycin and 6-DMAP + CHX, which we routinely use to activate bovine oocytes (Meng et al., 2011). Then we compared ionomycin, ethanol, or their combination to determine whether they would promote development of parthenogenetic embryos. The results showed that ionomycin, ethanol, or their combination, plus 6-DMAP and CHX treatment activated hamster oocytes, as judged by cleavage rates.

These results, in addition to the high incidence of spontaneous activation of hamster oocytes in this study and as previously reported by others (He et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2002), show that hamster oocytes are easily activated by artificial methods. Embryo development, however, requires changes to the culture system, and the lack of further development is attributed to an insufficient culture system and not activation.

We compared the genetic profiles of spontaneously activated and AA hamster oocytes. Immunocytochemical staining showed that the chromosome/DNA patterns of spontaneously activated oocytes lagged behind those of AA oocytes. At 3 hours postincubation/activation, most spontaneously activated oocytes were at anaphase/telophase of second meiosis, whereas most AA oocytes had formed two pronuclei by this time. Almost all spontaneously activated oocytes formed a single pronucleus (Fig. 2), whereas AA oocytes formed two pronuclei (Fig. 4).

Upon comparing their ability to develop in vitro, none of the spontaneously activated oocytes cleaved when they were cultured under the same conditions as AA oocytes, with the latter developing to the hatching blastocyst stage. These results suggest that the mechanism for promoting parthenogenetic embryo development is initiated by artificial stimuli in the culture medium and not by spontaneous activation.

In summary, our data indicate that hamster oocytes can be AA with ionomycin or ethanol combined with 6-DMAP + CHX + CB treatments. The resulting parthenogenetic embryos then have the potential to develop through the two-cell block to the blastocyst stage when serial culture conditions are used. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the successful in vitro culture of parthenogenetic hamster embryos to the blastocyst stage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Utah Agriculture Experiment Station. G. Z., X. W., and H. W. received visiting scholarship from China Scholarship Council. The authors thank Dr. Barry Bavister, a world-renowned hamster embryologist (www.barryvavister.com), for both professional English editing and scientific opinions on this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Balakier H., and Casper R.F. (1993). Experimentally induced parthenogenetic activation of human oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 8, 740–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros C., Gonzelez J., Herrera E., and Bustos-Obregon E. (1978). Fertilizing capacity of human spermatozoa evaluated by actual penetration of foreign eggs. Contraception 17, 87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavister B.D., and Arlotto T. (1990). Influence of single amino acids on the development of hamster one-cell embryos in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 25, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatot C.L., Lewis-Williams J., Torres I., and Ziomek C.A. (1994). One-minute exposure of 4-cell mouse embryos to glucose overcomes morula block in CZB medium. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 37, 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatot C.L., Lewis J.L., Torres I., and Ziomek C.A. (1990). Development of 1-cell embryos from different strains of mice in CZB medium. Biol. Reprod. 42, 432–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatot C.L., Ziomek C.A., Bavister B.D., Lewis J.L., and Torres I. (1989). An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J. Reprod. Fertil. 86, 679–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Liu Z., Huang J., Amano T., Li C., Cao S., Wu C., Liu B., Zhou L., Carter M.G., et al. (2009). Birth of parthenote mice directly from parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 27, 2136–2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibelli J.B., Stice S.L., Golueke P.J., Kane J.J., Jerry J., Blackwell C., de Leon F.A.P., and Robl J.M. (1998). Cloned transgenic calves produced from nonquiescent fetal fibroblasts. Science 280, 1256–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collas P., Sullivan E.J., and Barnes F.L. (1993). Histone H1 kinase activity in bovine oocytes following calcium stimulation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 34, 224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienhart M.K., and Downs S.M. (1996). Cyclic AMP reversal of hypoxanthine-arrested preimplantation mouse embryos is EDTA-dependent. Zygote 4, 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner D.K., and Lane M. (1996). Alleviation of the “2-cell block” and development to the blastocyst of CF1 mouse embryos: Role of amino acids, EDTA and physical parameters. Hum. Reprod. 11, 2703–2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D.S., and Bavister B.D. (1995). Zona pellucida escape by hamster blastocysts in vitro is delayed and morphologically different compared with zona escape in vivo. Biol. Reprod. 52, 470–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigo K., Yamauchi Y., Yazama F., Yanagimachi R., and Horiuchi T. (2004). Full-term development of hamster embryos produced by injection of round spermatids into oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 71, 194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Liow S., Chen M., Ng S., and Ge Q. (1999). Spontaneous activation of hamster oocytes in vitro. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 112, 1105–1108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Wang C., Guan J., Wang L., and Li Z. (2015). Changes of spontaneous parthenogenetic activation and development potential of golden hamster oocytes during the aging process. Acta Histochem. 117, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M., Boatman D.E., Albrecht R.M., and Bavister B.D. (1998). Intracellular divalent cation homeostasis and developmental competence in the hamster preimplantation embryo. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 50, 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Shi L., Zhang M., Yang H., Qin Y., Zhang J., Gong D., Zhang X., Li D., and Li J. (2011). Defects in trophoblast cell lineage account for the impaired in vivo development of cloned embryos generated by somatic nuclear transfer. Cell Stem Cell 8, 371–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutradis D., John D., and Kiessling A.A. (1987). Hypoxanthine causes a 2-cell block in random-bred mouse embryos. Biol. Reprod. 37, 311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaty Z., and Prather R.S. (1998). Strategies for activating nuclear transfer oocytes. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 10, 599–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa T., Ikeda S., Imai H., and Yamada M. (2002). Alleviation of the two-cell block of ICR mouse embryos by polyaminocarboxylate metal chelators. Reproduction 124, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan S.H., and Bavister B.D. (1990). Environmental variables influencing in vitro development of hamster 2-cell embryos to the blastocyst stage. Biol. Reprod. 43, 404–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan S.H., and Bavister B.D. (1998). Pantothenate stimulates hamster blastocyst development. Theriogenology 41, 209 [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan S.H., and Bavister B.D. (2000). Culture of one-cell hamster embryos with water soluble vitamins: pantothenate stimulates blastocyst production. Hum. Reprod. 15, 157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan S.H., Bavister B.D., and Tasca R.J. (1991). Energy substrate requirements for in vitro development of hamster 1- and 2-cell embryos to the blastocyst stage. Hum. Reprod. 6, 64–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan S.H., Clayton M.K., and Bavister B.D. (1995). Analysis of stimulatory and inhibitory amino acids for development of hamster one-cell embryos in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 42, 188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q., Wu X., Bunch T.D., White K., Sessions B.R., Davies C.J., Rickords L., and Li G.P. (2011). Enucleation of demecolcine-treated bovine oocytes in cytochalasin-free medium: mechanism investigation and practical improvement. Cell. Reprogram. 13, 411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses R.M., and Kline D. (1995). Release of mouse eggs from metaphase arrest by protein synthesis inhibition in the absence of a calcium signal or microtubule assembly. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 41, 264–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr-Esfahani M.H., Winston N.J., and Johnson M.H. (1992). Effects of glucose, glutamine, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and oxygen tension on the concentration of reactive oxygen species and on development of the mouse preimplantation embryo in vitro. J. Reprod. Fertil. 96, 219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse P. (1990). Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature 344, 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.E., Chung H.M., Ko J.J., Lee B.C., Cha K.Y., and Lim J.M. (2000). Embryotropic role of hemoglobin and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in preimplantation development of ICR mouse 1-cell embryos. Fertil. Steril. 74, 996–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presicce G.A., and Yang X.Z. (1994). Parthenogenetic development of bovine oocytes matured in vitro for 24-hours and activated by ethanol and cycloheximide. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 38, 380–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragina N.P., Schlosser K., Knott J.G., Senagore P.K., Swiatek P.J., Chang E.A., Fakhouri W.D., Schutte B.C., Kiupel M., and Cibelli J.B. (2012). Downregulation of H19 improves the differentiation potential of mouse parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 21, 1134–1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schini S.A., and Bavister B.D. (1988a). Development of golden hamster embryos through the two-cell block in chemically defined medium. J. Exp. Zool. 245, 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schini S.A., and Bavister B.D. (1988b). Two-cell block to development of cultured hamster embryos is caused by phosphate and glucose. Biol. Reprod. 39, 1183–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.S., Yue K.Z., Zhou J.B., Chen Q.X., and Tan J.H. (2002). In vitro spontaneous parthenogenetic activation of golden hamster oocytes. Theriogenology 57, 845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K., and Ozil J.P. (1994). Dynamics of the calcium signal that triggers mammalian egg activation. Int. Rev. Cytol. 152, 183–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno H., and Kamiguchi Y. (1997). Parthenogenetic activation of Chinese hamster oocytes by chemical stimuli and its cytogenetic evaluation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 47, 72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda Y., and Chang M.C. (1976). In vivo and in vitro fertilization of hamster, rat and mouse eggs after treatment with anti-hamster ovary antiserum. J. Exp. Zool. 195, 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann U., Vienken J., Halfmann J., and Emeis C.C. (1985). Electrofusion: a novel hybridization technique. Adv. Biotechnol. Processes 4, 79–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]