Abstract

Purpose: In an effort to counteract the differences in improvement in survival rates of adolescents and young adults (AYA), compared to other age groups with cancer, the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics established an AYA cancer program. This study was conducted to gather feedback from AYAs in an effort to generate actionable data for program development.

Methods: The target population included patients aged 13–31 treated for malignancy in one of the following disease sites: central nervous system, leukemia, lymphoma, neuroendocrine, sarcoma, and thyroid. A series of four focus groups was held to identify and describe gaps in care and provide suggestions for program development. A convergent parallel mixed-methods design was used. Qualitative data were derived from focus group discussion and free-response survey questions, while quantitative data were derived from objective survey questions and electronic medical record data.

Results: Across the four focus groups, 24 different AYAs participated, ranging from 8 to 19 individuals per session. Topics discussed included the following: communication, treatment experience, and overall AYA program; finances, work and school, and late effects; relationships, emotions, and spirituality; and body image, infertility, sexuality, risky behavior, and suicide. The results of the analyses corroborated what makes AYAs different from other age groups. The primary theme identified was the unique relationships of AYAs, which can be thought of along a continuum.

Conclusions: Information obtained from these analyses has been used to inform specific projects within the development of the AYA program to address patient-identified gaps. For AYAs, the importance of relationships along a continuum should be considered when developing an AYA program, in addition to potential policy or health service research utilization in the future.

Keywords: : survivorship, oncofertility, psychosocial, social support, treatment, clinical trial

Introduction

Once every 8 minutes in the United States, a young adult hears the words, “you have cancer.”1 Survival rates for adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients, in particular those aged 15–39, in the United States have not improved at the same rate as other age groups.1,2 Several factors are likely to play a part in this: the biology of certain cancers affecting the AYA age groups has been found to be different; the biology of AYA patients may differ in how they respond to varying doses of therapies than older or younger patients; the lack of consistent, effective insurance impacts access to health care services; an absence of AYA-specific clinical trials to advance treatment options; and the psychosocial needs specific to patients in the transition from childhood to adulthood may make adherence to traditional therapies more challenging.1 According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), these patients may fall into a gap between pediatric and adult practices.1 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) created Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for AYAs in 2012 in an effort to increase the previous 30 years' stagnant survival rates for this age group.3,4

According to the NCI's AYA Oncology Progress Review Group, the AYA age range is defined as those diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39.1 However, other organizations have used varying age ranges, from 13 to 39. Historically, AYA programs have been housed in either pediatric oncology or medical oncology hospital-based settings.5 Both pediatric and adult approaches have strengths and weaknesses that should be considered when establishing an AYA program.5

The Stead Family Children's Hospital (SFCH) and the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center (HCCC) at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) joined forces to develop an AYA Cancer Program to address the unique needs of those patients who are 13–31 years of age. The AYA cancer program has been designed as a consultative service to coordinate care for AYA cancer patients among clinicians and supportive care services found in both the SFCH and the HCCC. Development of the program began in 2015 with core team members, including a medical director (pediatric oncology), co-medical director (medical oncology), nurse practitioner (pediatric oncology), nurse coordinator, and administrator. The primary disease sites for the initial development of the AYA program are as follows: central nervous system, leukemia, lymphoma, neuroendocrine, thyroid, and sarcoma. The 13–31 age distribution, along with the primary disease sites at the start of the AYA program were chosen based upon historic patient data and the expertise and resources available from both adult and pediatric providers.

The life changes and demands of this age group, even without a cancer diagnosis, are fast paced. After treatment is complete, challenges continue to face these survivors, including financial stress, infertility, and learning to become one's own advocate, while transitioning to survivorship.

The program aims to address multiple areas of need among AYA cancer patients, including increasing access to clinical trials, oncofertility counseling and preservation, psychosocial programming, cancer predisposition services, and transition to survivorship programs. However, the details of how each component can best be designed require the input of AYA patients who have utilized services. To gather this feedback, the multidisciplinary AYA cancer program planning team (including the core team listed above and other colleagues with an interest in the AYA program) implemented a series of four focus groups to generate actionable data related to gaps in AYA cancer care. The team hoped to learn how to strengthen programmatic efforts and identify interventions that are not currently planned, utilizing a patient-centered approach.

Methods

The overall design of this initiative utilized a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative methods with the ultimate goal of generating effective and actionable data for program building. Specifically, a convergent parallel mixed-methods design was used, where qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed simultaneously.6 Mixed-methods approaches have also been shown to be useful tools across a wide variety of disciplines, making it an ideal fit for the interdisciplinary nature of this project.6

A multidisciplinary team of clinicians, social workers, patient education specialists, and marketing specialists from both SFCH and the HCCC came together with a health services researcher from the College of Public Health to identify the goals of the sessions and to design and implement the sessions. These discussions were driven by a set of a priori hypotheses, which were aligned with the unique needs and mechanisms of support for AYAs (Appendix A). An application to the UIHC IRB was submitted and a waiver obtained, as this project fell under the quality improvement category and was not considered human subjects research.

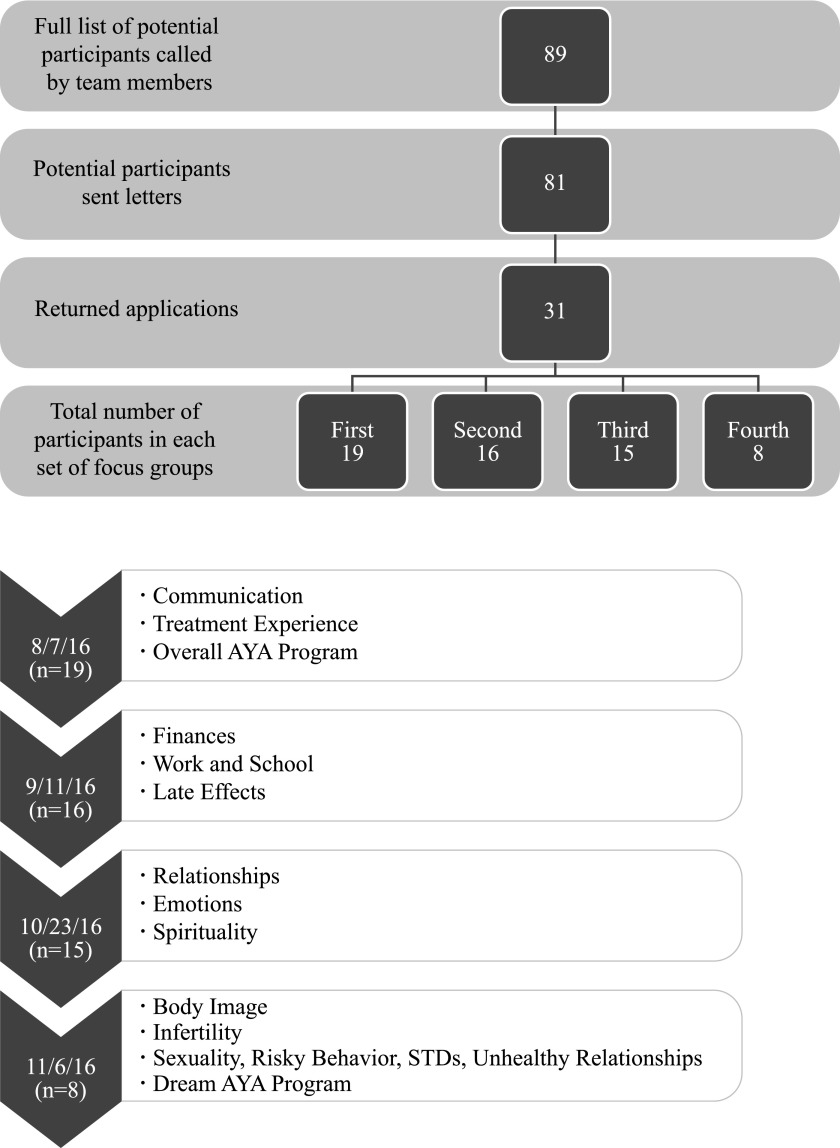

Recruitment

During the initial planning for this project, the multidisciplinary team developed a list of 89 potential AYA patients whom they had come into contact with through their professional roles. Based on the wide geographic spread of our patient population and prior difficulties recruiting AYA patients for focus groups, potential participants were selected due to their likelihood of participation and geographic proximity to the session sites. Based on the list of 89 participants, team members called each patient on the telephone to gauge their interest in participating. If the patient was a minor, the parents were first called, followed by the patient, if given consent. After discussion with the patient (and parent, if applicable), 81 patients expressed interest in participating in the focus groups and were sent a letter with an application. Of those 81 patients who expressed interest, 31 individuals returned their applications (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Focus Group Sample and Discussion Topics by Session. AYA, adolescent and young adult.

Purposeful sampling of focus group participants was used due to intent to understand the AYA experience, rather than generalize to a larger population.6 The target population for this project were all those who could potentially be seen at UIHC between the age of 13 and 31, who have been diagnosed with cancer in one of the six primary disease sites. By conducting targeted focus groups, the team hoped to gather together AYAs to learn from different perspectives regarding their needs throughout the cancer trajectory (e.g., diagnosis, treatment, end of treatment, survivorship, and transition from pediatric to adult settings). Due to the unique perspective and feedback, some patients outside of the six primary disease areas were included. As a result, we had three participants whose diseases were classified as “other.”

Session design and implementation

The team designed four sessions that would cover each of the topics of interest (Fig. 1). Questions to guide the discussions to cover the topics of interest were developed and vetted by the multidisciplinary team (Appendix B). In addition, an exit survey to be given to participants after each session was developed by the team. After the completion of the first three focus groups, information was gathered from participants through an additional survey administered during the meet-and-greet time at the following focus group session. As a result, targeted follow-up questions could be asked of participants after the team had a chance to review and discuss the prior sessions' feedback.

Moderators were trained to lead the sessions, and a moderator's guide was developed for each session, to standardize the discussion. For the first three sessions, participants were divided into three groups, based on age. For the fourth session, participants were separated into two groups, based on sex, to minimize discomfort when discussing issues related to self-image, relationships, and sexuality. The first session was both video and audio recorded, while the subsequent sessions were audio recorded only due to the cost of video without added benefit for transcribers or coders.

Analyses

Focus group data and free-response survey questions were analyzed qualitatively, while survey and electronic medical record (EMR) data were analyzed quantitatively. Recordings from each focus group were transcribed and coded into theme categories. DDS Player Standard Transcription Module was used by the Social Science Research Center (SSRC) at the University of Iowa to transcribe the audio files from each focus group.

Demographic information collected from the EMR included the following: current age, gender, race, ethnicity, address, primary insurance, and secondary insurance. Rurality was accounted for using Urban Influence Codes (UICs).7 UICs are a classification mechanism that distinguishes counties based on metropolitan and nonmetropolitan status.7 Metropolitan counties are categorized based on their population size of the metro area, while nonmetropolitan counties are classified based on the size of the closest city or town and proximity to metropolitan and micropolitan designated areas.7 Patient primary address at the time of the focus groups was utilized to determine which “zone” within Iowa the patient lived in. Zone data are utilized internally to UIHC to demonstrate distance from the hospital and marketing region. Finally, primary insurance was extrapolated to determine if the participant utilized a public or private payer. Quantitative data were entered into STATA SE-15 for analyses.

Results

The target population included all those treated for malignancy between the age of 13 and 31 in one of the following disease sites: central nervous system, leukemia, lymphoma, neuroendocrine, sarcoma, and thyroid at UIHC from 2000 to 2016 (Table 1). The full sample of focus group participants included 24 different AYAs, with participation ranging from 8 to 19 individuals across the four focus groups (Table 1). Age at diagnosis ranged from 3 to 24 years of age and current age at participation in the groups ranged from 15 to 34 years of age. The average number of years from diagnosis to participation in the focus groups was 5 years (median of 3 years; range of 0–16 years).

Table 1.

Description of Sample (n = 24)

| Characteristic | Number of participants (percentage) | UIHC AYAs from 2015 (comparison group) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Pediatric (≤12) | 1 (4%) | |

| Adolescent (13–17) | 15 (64%) | 30% |

| Young adult (18–34) | 8 (33%) | 70% |

| Current age | ||

| Adolescent (13–17) | 6 (25%) | |

| Young adult (18–34) | 18 (75%) | |

| Disease | ||

| Brain/CNS | 2 (8%) | 11% |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 11 (46%) | 40% |

| Neuroendocrine/Thyroid | 1 (4%) | 13% |

| Sarcoma | 7 (29%) | 30% |

| Other | 3 (13%) | 6% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 (50%) | 43% |

| Female | 12 (50%) | 57% |

| Race (White) | 22 (92%) | 90% |

| Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic) | 23 (96%) | 94% |

| Insurance Coverage | ||

| Private | 16 (67%) | 49%a |

| Medicaid | 6 (25%) | 45%a |

| Dual eligibleb | 2 (8%) | |

| Metropolitan (UIC 1–2)c | 13 (54%) | d |

| Nonmetropolitan (UIC >2)c | 11 (45%) | |

| UIC 5 | 3 (13%) | |

| UIC 6 | 6 (25%) | |

| UIC 8 | 2 (8%) | |

| Iowa Zone | ||

| Zone 1 | 9 (38%) | 32% |

| Zone 2 | 0 | 11% |

| Zone 3 | 6 (25%) | 8% |

| Zone 4 | 3 (13%) | 7% |

| Zone 5 | 2 (8%) | 9% |

| Zone 6 | 2 (8%) | 7% |

| Zone 7 | 0 | — |

| Zone 8 | 1 (4%) | 2% |

| Zone 9 | 1 (4%) | 8% |

| Zone 10 | 0 | 6% |

| Outside of Iowa | 0 | 12% |

Insurance coverage for all UIHC AYA patients with an inpatient stay was used as the comparison group.

Dual eligible participants were those covered by Medicare as primary and Medicaid secondary; comparison data not available.

Urban Influence Codes (UIC) were determined based on the permanent address of the participant; nonmetropolitan areas are delineated into micropolitan or noncore using guidelines established by the Office of Management and Budget; generally speaking, the larger the UIC, the more rural the location.7

Metropolitan code data are not available.

AYA, adolescents and young adults; UIHC, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.

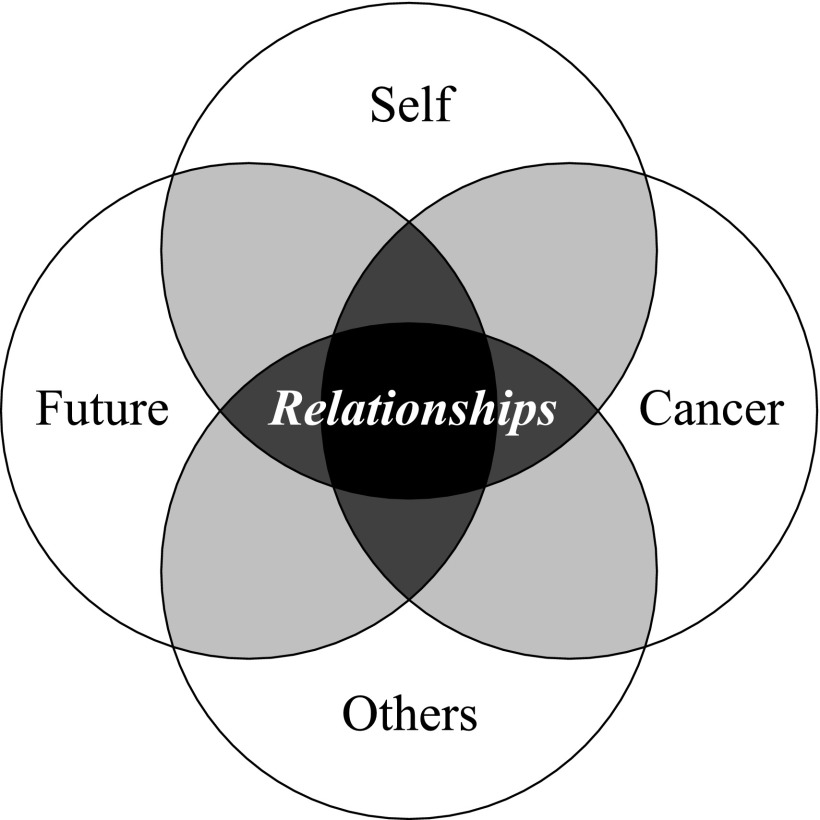

After combining data from the focus groups and surveys, our results corroborate what makes AYAs different from traditional pediatric or adult populations. Thoughts expressed by participants throughout the four focus groups highlighted unique relationships of AYA cancer patients as the primary theme. These relationships can be thought of along a continuum: Relationship to Self, Relationship to Cancer, Relationship to the Community and Others, and Relationship to the Future (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Results–Primary Themes Identified: Intersecting Relationships.

Relationship to self

The first identified theme that AYA patients expressed was regarding how their cancer diagnosis changed their Relationship with Themselves. In the AYA age range, one is focused on self-discovery and definition, and our participants relayed that cancer impacted them during this important time (Table 2). While more than half of participants felt that their cancer diagnosis and treatment did not have a large impact on their ability to continue to participate in activities that were important to them (9 out of 15), a majority of them described on-going emotional and psychological needs stemming from their diagnosis and therapy (9 out of 15). Most were offered and received some counseling services during treatment (9 out of 15). While most practitioners incorporate questions regarding risky behaviors, domestic violence, and emotional distress during their visits, we were surprised to learn that our participants suggested that these topics be addressed more than once, with the majority of respondents suggesting at least twice per year (6 out of 8). Finally, participants noted that issues related to changes in body image occur, but are not typically addressed by their providers (7 out of 8).

Table 2.

Results by Age at Diagnosis: Relationship to Self

| Adolescent | Young Adult | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Session 3a | n = 11 | n = 4 | ||

| Did you receive counseling services at any time? | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Was your spiritual distress highest at diagnosis and/or during treatment? | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| After your cancer diagnosis, please select how the following attributes of your life changed: | Quite a Bit or A Great Deal | Not at All, Very Little, Somewhat | Quite a Bit or A Great Deal | Not at All, Very Little, Somewhat |

| Ability to participate in hobbies/activities | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Emotional changes (mood, anxiety, etc.) | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Spirituality | 2 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| Session 4 | n = 7 | n = 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did cancer affect your body image?a | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| How often would you like to discuss the following with your medical team: | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year |

| Sex | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Drugs | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Suicide | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Risky Behavior | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Quotes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I felt like honestly a lot of my like sadness or loneliness actually came later like after treatment just feeling alone as a survivor and you know I'm not being surrounded by other people who have gone through what I've gone through. I think I felt more emotion afterwards.” | ||||

| “It wasn't until recently [after I began having anxiety attacks] that they gave me the option that we have a psychologist that can come in and talk to you and give you resources… that was something missing in my treatment.” | ||||

| “I've been going… completely insane and mad… I had depression and insomnia… I'm sick and tired of going through this… It's not even the fact that I had cancer, it was that fact that… it won't stop.” |

Not all participants answered all questions, so results do not always equal the number of participants.

Relationship to cancer

The second theme identified pertains to how AYAs grow and develop their Relationship to Cancer. How the AYA patient is helped to understand their cancer diagnosis, treatment options, side effects, and sequelae can be enhanced (Table 3). Eight of the eighteen respondents recall being offered a clinical trial. However, review of medical records shows that one patient was on a treatment-only study, nine were on nontreatment studies (e.g., biology, registry, or other studies), and six were on a combination of treatment and nontreatment studies. Our a priori assumption was that AYA patients utilize electronic information sources and social networking to gather information and support. We were surprised that only eight out of eighteen AYAs utilized the internet for information and only one used social media. Participants suggested that paper resources created in a succinct and eye-catching manner be given to AYAs and reviewed at varying time points throughout their treatment and survivorship process. In addition, they suggested that a list of reputable online resources should be provided to all AYAs. All participants felt that their treatment team gave them realistic expectations about their diagnosis and treatment. This response was different than what may have been expected and documented in prior research.8,9

Table 3.

Results by Age at Diagnosis: Relationship to Cancer

| Adolescent | Young Adult | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Session 1a | n = 11 | n = 8 | ||

| Were you offered a clinical trial? | 6 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Did you go online to understand your diagnosis or seek out more information? | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Did you use social media to understand your diagnosis or seek out more information? | 0 | 11 | 1 | 7 |

| Do you feel you were given realistic expectations about your diagnosis? | 11 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Session 2 | n = 12 | n = 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did anyone on the treatment team speak with you or your family members about financial concerns during your treatment? | 11 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Did you or your family members experience financial stressors as a result of your treatment? | 1 | 11 | 2 | 2 |

| Did financial stressors affect your parents' employment statuses? | 3 | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| Did anyone share anything with you about nonprofit organizations that was helpful? | 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Quotes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “My first reaction was ‘I'm going to die!’… I remember you [nurse practitioner] asked me what my number one fear was and I told you it was dying and you told me that cancer isn't a death sentence, just because you have cancer doesn't automatically mean you're going to die so that was really reassuring… I actually had a chance to live.” | ||||

| “Obviously it [my treatment] worked out but it would have been nice if they discussed it and listened to what I was saying.” |

Not all participants answered all questions, so results do not always equal the number of participants.

A cancer diagnosis and treatment can also impact patient and family finances, insurance status, and available resources. Most of our participants were privately insured (16 out of 24 total participants) and few noted some financial difficulties that they or their families faced. Three out of the 16 participations in the second focus group noted that their family members experienced financial stressors due to their treatment, and four participants reported that their parents' employment statuses were affected by financial stressors.

Relationship to the community and others

AYAs negotiate relationships with many different people, and those Relationships with the Community and Others may be impacted by cancer (Table 4). Most participants found that relationships with parents and friends changed after their cancer diagnosis (9 and 8, respectively, out of 15), while not changing the dynamics with their siblings as often (2 out of 15). In addition, there was strong support for the idea that linking with other patients of similar age who are undergoing cancer treatment is crucial for the AYA patient. The consensus of our participants was that it is more important to be in a treatment setting that includes peers close to age, than with exact diagnoses. Also, requests for increased connections either in person or virtually to patients of a similar age and cancer status for peer-to-peer support were strongly desired.

Table 4.

Results by Age at Diagnosis: Relationship to Community and Others

| Adolescent | Young Adult | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Session 3a | n = 11 | n = 4 | ||

| After your cancer diagnosis, please select how the following attributes of your life changed: | Quite a Bit or A Great Deal | Not at All, Very Little, Somewhat | Quite a Bit or A Great Deal | Not at All, Very Little, Somewhat |

| Relationships with your parents | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Relationships with your siblings | 2 | 9 | 0 | 4 |

| Relationships with your extended family | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Relationships with your friends | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Relationships with romantic partners | 1 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Session 4a | n = 7 | n = 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often would you like to discuss the following with your medical team: | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year |

| Domestic Violence | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Unhealthy Relationships | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Fertility | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Quotes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I just don't think I was prepared for how [low I felt]… I didn't see my friends all summer and then when I went back to school they were very cautious… it was a lot of being with my family and not seeing anyone else.” | ||||

| “Even here with everyone going on with this, I feel more of a connection to most of you here than with some of my friends back at home because you can share the experiences that I [went through]… It's fun to know all these people are like me… it's just nice to know that there a lot people that are going through [something similar to me].” |

Not all participants answered all questions, so results do not always equal the number of participants.

Relationship to the future

When AYAs are diagnosed with cancer and start treatment, it is important that they be given realistic expectations regarding their prognosis, but also hope for the future (Table 5). This allows for an appropriate Relationship to the Future to develop as the AYA maneuvers through diagnosis and treatment, and into survivorship. Almost all of the participants recall being told about potential side effects of their treatment and the need for continued surveillance for cancer recurrence and therapy-related side effects (14 out of 16). Most participants identified that their cancer treatment had at least one long-term side effect that they are still managing (15 out of 16). For older AYAs, issues regarding therapy-related infertility were also discussed, and there is a need for a much more robust and comprehensive oncofertility program integrated into AYA cancer care. While financial barriers were not noted in a prior focus group session, this came up as a need to address programmatically.

Table 5.

Results by Age at Diagnosis: Relationship to the Future

| Adolescent | Young Adult | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Session 2a | n = 12 | n = 8 | ||

| Do you remember being told about the possible late effects (problem you may experience after you have completed treatment)? | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Do you know about the ongoing monitoring needs that you have, based on the treatment you received? | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Has there been any major part of your life that has been affected by the long-term side effects of treatment? | 11 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Did your cancer diagnosis impact your decision regarding your future school or career (positively or negatively)? | 12 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Session 4a | n = 7 | n = 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have any known fertility issues? | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Did you undergo fertility preservation? | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| How often would you like to discuss the following with your medical team: | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year | ≥Monthly | ≤Twice per year |

| Fertility | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Quotes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Now that I've gone through everything, I've found out what I want to do when I get older. I want to become a doctor and help people… I've never thought of having a back-up plan because that's been my main goal ever since I [finished] treatment is going to Iowa, studying medicine, and becoming a doctor.” | ||||

| “One thing that didn't really [expect]… is how stressful not having cancer is… [after receiving confirmation from other participants] now that I'm done, now I have responsibilities again. It's not like I'm done. I still have to worry about getting it a second time more than a normal person has to worry about getting it a first time… [after receiving confirmation from other participants] … And then when I go and get my check-ups every 3 months, the like week leading into it is like the most stressful.” | ||||

| “This [fertility] is one of those weird topics because at 17 you- you don't really realize the social implications of not being able to have children. But… how do you explain that to somebody at that age? So I don't know. I think that was what I was most angry about. I didn't realize until I was maybe 20 or 21 that like society puts a lot more pressure on people who like are of the age to have children to do so.” |

Not all participants answered all questions, so results do not always equal the number of participants.

Discussion

As AYAs develop their identities and autonomy, a cancer diagnosis can challenge various developmental milestones and have lingering physical and psychosocial effects, outside of the immediate focus on the treatment of the disease.10 Given the age span of more than 25 years, differences in provider practice patterns, provider settings, available resources, access to clinical trials, psychosocial professionals, patient care support mechanisms, and others, care may be further fragmented.10

Underscoring the significance of the previously mentioned difficulties of providing care to AYAs, it is vital to keep in mind that while establishing the necessary skills for autonomous decision-making, younger AYAs still rely on their families significantly, while seeking other aspects of support from those outside the family (e.g., social support from peers). However, as AYAs get older, they begin to establish stronger, more long-term support networks outside the family, and many fall back on family support and help navigate the cancer process. A cancer diagnosis and treatment can defer or delay the development of mature relationships. People on whom AYA patients thought they could rely during their diagnosis and treatment may not have the adequate tools to help the AYA patient as much as they would like (e.g., financial resources, time off of work, and emotional stability). Furthermore, as this is the time of life that many young people are defining who they want to become and what their future will be, a cancer diagnosis can be especially impactful.

Many of the responses elicited during these feedback sessions validated the need for a comprehensive AYA program tailored to specifically meet the needs of the AYA cancer patient population. Program development under the premise of strengthening the myriad relationship needs of the AYA allows the care team to formulate programming that best meets the needs identified by patients. While happy to learn that clinicians provide education materials and screen for psychosocial needs during treatment, we were unaware that our panel would prefer that these topics be addressed at multiple time points during diagnosis, treatment, and after transition to survivorship.

Our intent with these focus groups that utilized a mixed-methods approach was to gather information that was important to the participants to build a strong patient-driven AYA Cancer Program. While the design is not meant to represent a larger AYA population, participants were representative of the AYA cancer patients seen at UIHC in the previous year (2015), when comparing demographic, insurance, geographic, and diagnosis data (Table 1). One limitation in our sample compared to the general patient population is age at diagnosis. The majority of our participants (66%) were diagnosed as adolescents, which was aligned with our original sample of 89 participants, of which half (50%) were diagnosed when younger than 18 years. Overall, the majority of current AYA patients at UIHC are diagnosed as young adults. Most focus group participants are now young adults (71%), many of whom are several years post-treatment. Their recollections may be different than their experiences at the time, and with a median time of 3 years and a small sample size, we were unable to do any further subgroup analyses to determine how recollections and feedback change over time. It was important for us to seek input from patients who can now reflect on their experience to give insight into building the program. This is of particular importance for the population of AYAs who may have been diagnosed when younger than 13 years or for those who may be several years post-treatment and have transitioned into survivorship. It should be recognized that all pediatric cancer survivors will 1 day be a part of a different subset of the AYA cancer population. The results of our study provide evidence that the needs of these patients are also unique and should be considered throughout the program development process. Our focus groups have provided crucial information from the perspective of the AYA patient as we seek to build a robust, collaborative, and comprehensive AYA cancer program.

A second limitation of our study is a relatively small sample size, both within (adolescent vs. young adult participants at diagnosis) and across focus groups. The fourth focus group had eight participants, with only one diagnosed as a young adult. However, our first focus group had 19 participants, eight of whom were diagnosed as young adults. This is important to keep in mind, given the limited sample size and lack of full participation for all survey questions. Future focus groups should be selected to reflect the current patient population so that variation in individuals' experiences based on time from treatment can be further delineated.

Third, due to the anonymous nature of our survey design, we cannot perform additional subgroup analyses (e.g., compare survivors 5 years from treatment to those currently under treatment or transitioning to survivorship), which is a limitation of the study. Although this would provide additional context for the survey findings, it is not possible due to the survey design.

Given that there is no standardized guideline explaining how to develop an AYA Cancer Program, the approach utilized in this study may be helpful to others. However, there are important limitations to keep in mind, which are inherent in the design. Reaching out to AYAs effectively and maintaining engagement throughout the focus groups were difficult. This reinforces our prior experience showing how difficult it can be to fully engage AYA patients living across a wide geographic area and led us to sample patients from different zones within Iowa with varying proximity to our institution. Further strategies to increase engagement are needed. In addition, it is important to keep in mind the cancer continuum and the AYA age spectrum when developing an AYA Cancer Program. Other organizations should keep these successes and opportunities for improvement in mind when using this sort of approach.

During a time of development already fraught with life-affecting decisions, the diagnosis of cancer requires increased support for our AYA patients. Given the findings of our study, combined with the current landscape of AYA cancer, the importance of the patient perspective is vital, especially concerning potential practice-changing and policy-changing initiatives.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable efforts of the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics team members, including Jen Adams, Justin Kahler, Jill Kain, Amanda Reimann, John Werner, and Cynthia West. We would also like to thank the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Iowa Stead Family Children's Hospital for their support of the AYA program. We would like to express our gratitude to Marcia Ward at the University of Iowa College of Public Health, Department of Health Management and Policy, for her methodological and study design guidance. We would also like to thank the Iowa Social Science Research Center for their assistance with transcribing and coding the focus group data. Last, this work would not have been possible without funding from the Iowa Cancer Consortium and the Iowa Department of Public Health.

Appendix A: Hypotheses

To develop the moderator guides used to facilitate focus group discussion, several a priori hypotheses were generated prior to each session's design. These were as follows:

1. AYA patients have different needs regarding information related to a cancer diagnosis.

2. Different mechanisms for support of AYA patients at the time of diagnosis are needed.

3. Because of the heterogeneity of patient ages, diagnoses, treatment teams, and treatment options, there are varying degrees of involvement in cancer decision-making among AYA patients.

4. The current paradigms that determine location and treatment teams based on age of the patient may not optimally address the needs of AYA patients and their families.

5. AYA patients have unique financial circumstances that are not currently being addressed.

6. AYA patients have unique needs related to school or work that are not adequately addressed.

7. The late effects of AYA cancer therapies are not consistently and optimally addressed before, during, or after therapy.

8. Services to address late effects and survivorship need to be tailored to AYA patients.

9. Programs are needed to assist AYA patients in navigating the challenges in relationships with friends, families, and partners after a cancer diagnosis.

10. AYA cancer patients face issues related to body image that are not currently apparent to clinicians.

11. Issues related to sexual dysfunction or infertility need to be addressed.

Appendix B: Focus Group Questions by Session

Session 1

Treatment Experience–Diagnosis

1. Please describe how you learned about your initial cancer diagnosis.

a. Where?

b. Who informed you?

c. Is this who you would have wanted–or someone else?

d. Who was with you when you were informed?

e. Is this who you would have wanted–or someone else?

f. How did you feel about the way you learned of your diagnosis?

g. How do you feel adolescents and young adults should ideally be informed of their cancer diagnoses?

2. What were some of the first things you did to learn more about your diagnosis?

a. Did you use any online resources?

b. Did WHO direct you toward these online resources?

c. Were you directed to any online resources that you did you not use?

3. Who, if anyone, did you talk to, to learn more about your diagnosis?

a. Friends and family?

b. Other current patients?

c. Survivors?

d. Mental healthcare providers?

e. Other healthcare providers?

f. Representatives of patient support organizations?

g. Others?

4. When do you feel would have been the best time to be given—not seek out yourself, but be given—additional information about your diagnosis?

a. Anyone not given additional information about your diagnosis?

b. Anyone given additional information that was not helpful?

c. What type of information do you prefer (printed material, online information, videos, etc.)? Why?

5. How was the ongoing communication regarding your diagnosis and plan of care? By “communications,” I specifically mean any information given or sent to you; I am not asking about the verbal discussions you had with your medical team.

a. How did you know when the news was positive or negative?

b. How, if at all, could this have been improved?

c. Were the communications understandable?

d. How, if at all, could this have been improved?

e. Did communications help guide your discussions with your medical team? That is, did the information you were given make your interactions with the medical team any easier?

f. How could this have been improved?

6. Was there anything about your diagnosis or treatment plan that you wish you had been told at an earlier time than you actually were? And why?

a. Anything that you wish you had been told later than you actually were? Why?

Treatment Experience–Communication

7. What are some of the ways that the UI or the treatment team included you in determining your treatment plan and ongoing care?

a. What are some of the ways you were not included in your care?

b. Was anyone more or less involved in deciding their treatment plan than they wanted to be?

c. Please describe your experience, including the others involved in deciding your treatment.

d. Was anyone involved in the discussion, who you wish had not been?

e. Was anyone not involved in the discussion, who you wish had been?

8. Did your medical team discuss different treatment options with you, specifically?

a. Did you feel your input on these options was respected, or did you feel that the “correct” option had already been picked for you?

b. Did you feel like you received adequate information on all the potential treatment options?

c. Were clinical trials offered to you as an option?

d. Was this option pursued—why or why not?

9. Did your medical team discuss things with you in a way that was easy to understand?

a. Did you know when the news was positive or negative?

b. How, if at all, could this have been improved?

10. Describe the communication between your UI team and local providers.

a. In what ways, if at all, could communication between providers be improved?

b. When changes were made to your appointments and schedule, were you always notified?

c. In what ways were you notified?

d. In what ways would you prefer to be notified?

Treatment Experience–Services and Amenities

11. What are some of the things you liked about the physical locations where you were treated (inpatient, outpatient, consultation, etc.)?

12. What are some of the things you did not like about the physical locations where you were treated?

a. Colors?

b. Furniture?

c. Privacy?

d. Space for visitors?

e. Lighting?

f. Temperature?

g. Refreshments?

h. Activities?

i. Technology?

13. Would you like to see a separate physical area where adolescents and young adults can receive their cancer treatment?

a. How important is it that you be with patients around your own age?

b. Reasons why it is/is not important?

c. How important is it that you be with patients who have the same/similar diagnosis?

d. Reasons why it is/is not important?

e. How do you believe your opinion did (or would) change at different ages?

f. Reasons for change, if any?

14. What supportive services were offered to you? Which of these services did you find to be particularly important or especially helpful? What services do you wish would have been offered that were not?

a. For any service: How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

b. Social services/social worker? How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

c. Nutrition? How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

d. Counseling? How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

e. Physical therapy/rehabilitation? How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

f. Did you receive any services from Child Life?

g. How were/were not these services helpful to you?

h. How, if at all, could this service have been improved?

15. Did anyone have any cultural considerations that were not taken into account by their treatment plan or medical team?

16. I want to be sure we have captured all your thoughts this afternoon. Was there anything else about your treatment experience that we have not already discussed that you thought was lacking or missing?

17. Was there anything that we have not already discussed that you would have changed or eliminated from your treatment experience?

Conclusion

18. Is there anything I did not ask you about with regard to your diagnosis and treatment experience that you think is important for the AYA program development team to know or understand as we analyze the discussions from this and other focus groups?

19. Briefly, is there anything you think would be important for the AYA program development team to know or understand as we develop questions for our next session (our next session will cover the effects that diagnosis and undergoing treatment have on personal, school, and work life)?

Session 2

Financial

1. Everyone in the group has received healthcare services from the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics or UI Children's Hospital for a cancer diagnosis. Let us start by going around the table and each person introduce yourself briefly by sharing your first name, what type of cancer you had or have, and what year you initially received your diagnosis.

2. Did you or your family have financial stressors as a result of your diagnosis? What were they?

a. During treatment?

b. After treatment?

c. Did it affect you or your parents' employment statuses?

d. How?

e. Did you or your family have difficulties with transportation?

f. Did you or your family have problems with lodging or accommodation needs for treatment?

3. Do you or your family have long-term financial stressors as a result of your therapy?

a. How did you overcome these challenges?

4. Did you have health insurance at the time of diagnosis?

5. Did anyone on the healthcare team speak to you or your family about financial concerns during your treatment?

a. What things could have relieved the financial stressors for you and your family?

b. Did anyone share any information with you about programs that may have been able to assist you with the financial burden?

c. If so, can you list the ones that you recall?

d. What assistance did you get from the programs you utilized?

6. Was there anything about the financial stressors of cancer care you wish would have been addressed, but were not?

School and Work

1. How did your cancer diagnosis affect your school experience?

a. Was the school willing to accommodate changes in needs?

b. Did teachers change their expectations for you in the classroom?

c. Did anyone educate your teachers and/or friends about your diagnosis?

2. How did your cancer diagnosis affect your work experience?

a. Was your place of work willing to accommodate your needs?

b. If not, can you think of anything that the medical team could have helped with in this regard?

c. Were your expectations at work adjusted appropriately?

3. Did your cancer diagnosis impact decisions about your future (school/career) choice?

a. If so, how?

4. Has anyone ever discussed your legal rights in the workplace or school setting?

a. FMLA, ADA, IEP, SSI

5. Who, outside of UIHC, helped you to cope with work or school challenges or questions?

a. Counselor, human resources, pastor, AEA, friends?

6. Was there anything about stressors related to school/work that you wish would have been addressed, but were not?

Late Effects

7. Late Effects are problems that occur as a result of your cancer diagnosis and/or treatment.

8. We would like to go around the table and have you share what late effects you have experienced.

a. Do you feel like you were prepared for this?

b. How could the medical team have better prepared you?

9. Do you recall being told about potential late effects from your treatment?

a. If so, when?

b. Who told you?

c. When would you have preferred the initial discussion of late effects have taken place for you?

d. If you were aware or had been made aware of potential long-term effects of treatment, would it have affected your decision-making process when deciding on moving forward with treatment?

10. As you take charge of your own health needs, do you know what types of follow-up you need for your long-term healthcare?

a. How have you taken responsibility for your healthcare beyond therapy?

b. What could be made available to you to assist you in doing this?

11. How many of you, by a show of hands, are aware that there are Cancer Survivorship Programs for both Pediatric and Adult patients?

a. Show of hands [make a note of the number hands up/down].

12. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about late effects of therapy?

Conclusion

13. Is there anything we did not ask you about with regard to your financial, school, and work experiences or late effects of treatment that you think is important for us to know or understand as we analyze the discussions from this and other focus groups?

14. Briefly, is there anything you think would be important for us to know or understand as we develop questions for our next session (our next session will cover the effects that diagnosis and undergoing treatment have on personal, school, and work life).

Session 3

Relationships

1. Did your cancer diagnosis affect your relationships with your family members?

a. If so, how?

b. Parents, guardians, spouses, and siblings?

2. Did your cancer diagnosis affect your independence? If so, how?

a. From your parents/significant others?

b. Making decisions about your medical care?

c. Making everyday decisions (where you go, what you do, etc.)

3. Did your cancer diagnosis affect your relationships with your FRIENDS?

a. If so, how?

4. Were you able to participate in the hobbies/activities that you did before your diagnosis?

a. If not, how did this affect you?

5. Did your cancer diagnosis affect your romantic relationships?

a. If so, how?

6. Did your cancer lead you to develop any new relationships?

a. Did any of those relationships include others undergoing treatment?

b. Did their treatment outcome have any impact on your life?

7. What tools would have been helpful in maintaining your relationships with family and friends (e.g., facilitated discussions, care conferences, handouts, brochures, social media, etc.)?

Emotional

8. What was your emotional response to your cancer diagnosis?

a. How did your emotions change over time?

9. How did you cope/deal with your emotional responses regarding your cancer diagnosis?

a. Whom did you talk to about your diagnosis?

b. Did you use any drug or alcohol to help you cope?

c. Did you withdraw or did you seek help from others?

10. Was counseling offered anytime during or after your diagnosis and treatment?

a. What type of counseling (e.g., formal services, psych nursing, social worker, psychologist, and psychiatrist)?

b. When would you have liked counseling to be offered?

11. Did you receive any type of emotional support from your medical team?

a. If so, who?

b. What helped?

c. What did not help?

12. Do you feel you have struggled with low mood, feelings of sadness loneliness, or depression due to your cancer diagnosis?

a. Did you tell anyone?

b. If so, whom?

13. Do you feel you have struggled with anxiety due to your cancer diagnosis?

a. Did you tell anyone?

b. If so, whom?

14. Did anyone talk to you at time of diagnosis, during or after treatment about thoughts of suicide or harming yourself?

a. Do you think that there is a certain time this should be addressed?

15. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about emotions?

Spirituality

16. When you think of spiritual support, what does that mean to you?

a. After participants have shared, give the following description of what a chaplain is and what services they offer:

Spiritual services at UIHC can help you find meaning in your illness, provide counseling for the emotional and spiritual distress of cancer and for the strain it can put on relationships, help you cope with your illness, can draw on your religious faith, provide sacraments and religious rights, and be a bridge to your religious community.

17. Did you experience any spiritual distress at time of diagnosis or throughout survivorship?

a. Did you find yourself asking why me or what is the meaning of this?

18. Do you feel your PARENTS OR OTHER FAMILY members experienced spiritual distress?

19. Were spiritual services INCORPORATED into your care at UIHC/Children's?

a. If so, how were they incorporated?

b. Who offered the services?

c. When were they offered?

d. Do you feel like the services offered were beneficial?

e. Were there any spiritual services you would have liked to be incorporated into your care?

20. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about spirituality?

Conclusion

21. Is there anything we did not ask you about with regard to your relationships, emotions, and spirituality that you think is important for us to know or understand as we analyze the discussions from this and other focus groups?

22. Briefly, is there anything you think would be important for us to know or understand as we develop questions for our next session (our next session will cover the effects that diagnosis and undergoing treatment have on body image, infertility, and sexuality)?

Session 4

Body Image

1. How did your cancer affect your appearance or body image?

a. How did you deal with these feelings over time?

b. Did this impact your interactions with other people?

c. Did you change your means of self-expression based on doctor recommendations or guidelines?

d. Examples: tattoos, piercings, clothing style change, etc.

2. Did anyone discuss with you the changes in your appearance that could occur because of our diagnosis or therapy?

a. Did you feel prepared for these changes?

b. What services were offered to you as a form of support through these changes?

c. What services were you not offered that you wish would have been offered to help with these changes?

3. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about body image?

Infertility

4. Did anyone talk to you at the time of diagnosis about a risk to your fertility status as a result of necessary treatment?

a. Was preservation offered and/or explained?

b. What would be the ideal way for your medical team to have this discussion with you?

c. Family members present/in private with no one else present

d. Did your feelings differ from your family members' on this topic?

e. Was the actual process for collection described?

5. Did you undergo fertility preservation?

a. If not, why?

b. If you did not preserve for any reason, do you reflect now and wish you had or could have?

6. Have you had any long-term emotional impact due to fertility issues?

7. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about fertility?

Sexuality, Risky Behaviors, STDs, Unhealthy Relationships

8. How open would you be with your medical team about sex, drugs, domestic violence, unhealthy relationships, suicide, risky behaviors, etc.?

a. What environment or discussion style would allow you to be the most open with your medical team about these issues?

b. Would you be honest in survey form?

9. How often do you think your medical team should readdress these topics?

10. Are there any other specific things you would like to address about these topics?

Gender Expectations

11. Have gender expectations/gender norms affected how you dealt/reacted to your cancer diagnosis/treatment?

a. Did you feel you needed to change your actions or responses based on gender expectations?

b. Examples: “boys don't cry, girls are emotional, boys are logical”

12. Is there anything that you think we should know that we did not discuss about your diagnosis and treatment that is unique to your gender?

Large Group Discussion

13. If you could have the perfect AYA program what would it look like?

14. Out of all the things we have talked about, what do you think is the most important for us to focus on?

15. After all of the topics we have discussed, what things have we missed that we should have talked about?

Author Disclosure Statement

The listed authors fulfill all four authorship requirements as stated in the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals (the “Uniform Requirements”) and have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.NCI. Report of the adolescent and young adult oncology progress review group. Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.AACR Cancer Progress Report 2017: Harnessing research discoveries to save lives. Philadelphia, PA: American Association for Cancer Research; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines Version 1.2017 Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. Fort Washington, Pennsylvania: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; October 16 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN. NCCN Announces New Guidelines for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Oncology. 2012. Accessed December30, 2016 from https://www.nccn.org/about/news/newsinfo.aspx?NewsID=310

- 5.Reed D, Block RG, Johnson R. Creating an adolescent and young adult cancer program: lessons learned from pediatric and adult oncology practice bases. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2014;12(10):1409–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban Influence Codes. United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service. Accessed January 25, 2017. from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes Accessed Jan 25, 2017

- 8.Bleyer A, Barr R, Ries L, et al. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2nd ed: Springer International Publishing; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zebrack B, Kent E, Keegan T, et al. ‘Cancer Sucks,’ and other ponderings by adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Psychos Oncol. 2014;32(1):1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015;20(2):186–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]