Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) often results in cognitive impairment, and trajectories of cognitive functioning can vary tremendously over time across survivors. Traditional approaches to measuring cognitive performance require face-to-face administration of a battery of objective neuropsychological tests, which can be time- and labor-intensive. There are numerous clinical and research contexts in which in-person testing is undesirable or unfeasible, including clinical monitoring of older adults or individuals with disability for whom travel is challenging, and epidemiological studies of geographically dispersed participants. A telephone-based method for measuring cognition could conserve resources and improve efficiency. The objective of this study is to examine the feasibility and usefulness of the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT) among individuals who are 1 and 2 years post–moderate-to-severe TBI. A total of 463 individuals participated in the study at Year 1 post-injury, and 386 participated at Year 2. The sample was mostly male (73%) and white (59%), with an average age of (mean ± standard deviation) 47.9 ± 20.9 years, and 73% experienced a duration of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) greater than 7 days. A majority of participants were able to complete the BTACT subtests (61–69% and 56–64% for Years 1 and 2 respectively); score imputation for those unable to complete a test due to severity of cognitive impairment yields complete data for 74–79% of the sample. BTACT subtests showed expected changes between Years 1–2, and summary scores demonstrated expected associations with injury severity, employment status, and cognitive status as measured by the Functional Independence Measure. Results indicate it is feasible, efficient, and useful to measure cognition over the telephone among individuals with moderate-severe TBI.

Keywords: : adult brain injury, cognitive function, neuropsychology, rehabilitation, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) can lead to potentially lifelong cognitive impairments, which contribute to limitations in daily activities and societal participation.1 It is important to assess cognitive status at various points in the post-injury period to identify problems that may require rehabilitation interventions, inform predictions regarding recovery and readiness for academic or vocational reentry, and monitor changes over time. Cognitive status may be measured in a variety of ways, including symptom checklists or rating scales such as the cognitive subscale of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM),2 which assesses the degree of independence in areas such as memory and problem-solving. However, the gold standard for cognitive assessment is the neuropsychological test battery, which provides standardized and objective measurement of demographically-adjusted performance in multiple domains of cognitive function. Neuropsychological batteries may be adapted to specific referral questions or research needs and can provide detailed, unbiased information on individual strengths and weaknesses relative to normative samples. A particularly valuable feature of neuropsychological testing is that the same measures, or parallel forms, may be repeated to examine recovery patterns. This type of longitudinal assessment is important not only for informing the care of individual patients, but for understanding the natural history of any disability or disease process that impacts cognition.

Prior studies of longitudinal neuropsychological functioning after TBI have often been limited to the first 1 or 2 years post-injury, and it has been suggested that cognitive recovery plateaus within approximately one year after injury.3,4 However, large-scale longitudinal initiatives such as the TBI Model Systems (TBIMS) program have enabled investigation of functional changes over much longer periods of time. For example, several studies have evaluated changes global functioning as measured by the FIM or Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E).5,6–8 Findings reveal considerable inter-individual heterogeneity in these outcomes, and suggest that change (either improvement or decline) is more common than stability many years post-injury.9 Notably, a substantial minority of adults across all age groups in the TBIMS experienced significant functional decline after the initial period of recovery.6 These findings are informative, but global measures of functioning are not ideal for studying more subtle changes over time. A neuropsychological assessment of cognition following TBI would facilitate examination of the trajectory of cognitive status over time and allow exploration of associations of cognitive status with other health-related and psychosocial outcomes.

Although a traditional battery of neuropsychological tests may be the gold standard for measuring cognitive performance, it represents a time- and labor-intensive approach. The typical battery is administered face to face (in person), which may be necessary for testing certain kinds of abilities or for certain applications requiring close clinical observation. However, there are situations in which in-person testing is either undesirable or unfeasible. Longitudinal studies are particularly expensive and prone to missing data, but can conserve resources and improve efficiency by using telephone-based methods for data collection. Some evidence suggests that individuals who are unable to attend in-person study visits may have different profiles of risk factors for cognitive decline or neurodegeneration compared to those who completed visits in-person10; in other words, excluding from research those who are unable to attend study visits can introduce systematic bias. It would be valuable, therefore, to identify a telephone-delivered cognitive assessment for use with individuals with TBI.

Many cognitive assessments have been developed or adapted for telephone use over the last two decades. Several of these tests were expressly designed to screen for dementia in the elderly (for a review, see Castanho and colleagues).11 Fewer have been created with the goal of sampling a variety of cognitive domains across the lifespan—that is, to serve as a brief alternative to an in-person battery. One such instrument is the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT),12 a multi-dimensional test of cognition designed for use in the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS).13,14 The BTACT is brief (15 min) and its items encompass a range of cognitive domains and ability levels.12 It has two alternate forms, is available in English and Spanish, and has strong psychometric properties as well as a robust normative sample that includes adults and older adults with and without cognitive decline. These advantages led to the inclusion of the BTACT in the National Institutes of Health Common Data Elements for TBI,15 but to date no prior study has used the BTACT in a TBI sample. The primary purpose of this study was to examine the feasibility of BTACT administration in a large sample of persons followed at 1 and 2 years post-TBI, and to gather initial data on its appropriateness and usefulness as a research tool in this population.

Methods

Participants

Participants were consecutive admissions who qualified for and were prospectively enrolled in the TBIMS multi-center national database (funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research) at nine inpatient rehabilitation hospitals. TBIMS enrollment requires that the individual has sustained a TBI defined by at least one of the following criteria: Glasgow Coma Scale score <13 on emergency department admission, loss of consciousness >30 min, post-traumatic amnesia >24 h, or trauma-related intracranial abnormality on neuroimaging. Additional inclusion criteria include: age 16 years or older at the time of injury, medical care received in a TBIMS-affiliated trauma center within 72 h of injury, transferred directly to an affiliated inpatient TBI rehabilitation program, and informed consent provided by legal proxy or participant. Additionally, participants in the current study had to be either English or Spanish speaking.

Procedures

The current study was a multi-center module project conducted under the larger TBIMS project infrastructure (www.tbindsc.org). The study was approved by institutional review boards at all participating centers. Study participants provided informed consent either independently or through a proxy during inpatient rehabilitation hospitalization or at the time of 1 or 2 year follow-up. The BTACT was administered over the telephone at one and two years post-injury, with a window of 2 months on either side of the anniversary date, coinciding with the standard TBIMS follow-up interviews. Data for the current study were collected between August 2014 and March 2017.

The standard BTACT assessment protocol12 was followed, including a script for introducing the measure and verbatim instructions for each subtest. Participants were asked to sit in a quiet environment to minimize distractions, and were instructed not to use paper, pencil or a calculator during the evaluation. In the TBIMS, data are collected from the best source (self or proxy); accordingly, if the follow-up interview was completed by proxy, the person with TBI was invited to come to the phone to attempt the BTACT. Performance was scored according to standard BTACT instructions, which specify stop rules based on time limits or incorrect responses. Reasons for noncompletion were also recorded. Data collectors were instructed to provide mild encouragement as suggested in the test manual, and to discontinue a subtest when (in their judgment) continuing the test would inflict unnecessary distress on the participant. The first author trained data collectors from all participating centers on the administration and scoring of BTACT via two teleconferences. Monthly teleconferences and an email list server were used to address questions or ambiguities in administration and scoring throughout the project. Most data collectors in the current study had a bachelor's degree, although there is no degree requirement for administering or scoring the BTACT. After enrollment targets were met, all data collectors were invited to complete an online survey about their experiences with the measure and the feasibility of its administration.

Measures

BTACT

The BTACT12 is a brief telephone-administered cognitive test battery.14 The BTACT was developed based on well-established, traditional neuropsychological tests (Table 1).16,17 Its subtests (described in order of administration below) were chosen to encompass a wide range of cognitive domains and ability levels.12

Table 1.

Descriptions of Subtests Included in the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT)

| Domain | Measure | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Episodic Verbal Memory | Immediate Recall of 15-item word list (RAVLT) | Total correct in 90 sec |

| (Optional: repetitions, intrusions, recall efficiency). | ||

| Delayed Recall of word list | Total correct in 60 sec | |

| (Optional: repetitions, intrusions, forgetting (Immediate-delayed recall)). | ||

| Working Memory | Digits Backward (WAIS-III) | Longest accurately recalled string |

| Reasoning | Number series completion | Number correct (five trials of increasing difficulty) |

| Executive | Animal Fluency | Number correct in 60 sec |

| (Optional: repetitions, intrusions) | ||

| Red Green: Alternating condition | Number correct in 32 trials | |

| Processing Speed | Red Green Test | |

| Simple: say STOP for red, GO for green | Number correct in 20 trials | |

| Reverse: opposite (Inhibition) | Number correct in 20 trials | |

| Alternating: simple/reverse (Flexibility) | Number correct in 32 trials | |

| Backward Counting Task | Total correct, errors, skips in 30 sec |

RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WAIS-III, Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition.

Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT).18,19

The RAVLT paradigm used in the BTACT consists of one 15-item immediate recall trial and a delayed recall trial. The 15-item word list is read to the participant with a 1-sec pause between words. The participants are then given 90 sec to freely recall as many words on the list as possible, in any order. Approximately 15 min later, participants are asked to again freely recall as many words as possible, without any cues from the examiner.

Digits Backward.20

Adapted from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III),20 this test requires participants to read a series of digits, beginning with a length of two, and are asked to orally reproduce the digits in reverse order. If participants incorrectly respond to a trial, they are given a second trial of the same span length. If both trials at the same span length are failed, the test is discontinued; otherwise, the span length increases up to a maximum of eight digits.

Number Series

Participants are read a sequence of five numbers and are asked to provide the sixth number in the series. Successful performance on this test requires the ability to recognize the pattern in the five number stimuli and use that pattern to derive the sixth number. Five different series are presented.

Animal Fluency

Participants are asked to verbally name as many animals as possible in 60 sec.

Red/Green Switch Test

During the first phase of this three-phase test, participants hear either the word “red” or the word “green,” and are asked to respond with either “stop” or “go,” respectively. During the baseline-reverse phase, they are asked to respond by saying, “go” to a “red” and “stop” to a “green” stimulus. This is followed by a mixed phase, where the task demands alternate unpredictably between the normal and reverse conditions.

Backward Counting Task

Participants are asked to count backwards by 1 starting at 100, as quickly as possible, for 30 sec.

FIM

The FIm2 was collected by trained research staff at 1- and 2-year follow-up via structured interview with the subject or caregiver. The FIM includes 18 items, each of which is scored on a scale ranging from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence). The FIM Total Score is calculated by adding the score from each of the 18 items (range: 18–126). FIM Motor (13 items; score range 13–91) and FIM Cognitive (five items; score range 5–35) subscale scores can be derived from the total score and have been validated for use with persons with TBI.21

Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended (GOSE)

The GOSE5,22 is a global outcome measure that assesses level of independence in and out of the home, return to work and leisure activities, changes in relationships, and other symptoms following TBI. Scores are assigned based on areas of function characterized by the greatest degree of disability (1 = death, 2 = vegetative, 3 = low severe disability, 4 = upper severe disability, 5 = low moderate disability, 6 = upper moderate disability, 7 = low good recovery, 8 = upper good recovery). It is administered via structured interview at 1 and 2 years post-injury as part of the TBIMS follow-up. The GOSE may be completed by the subject or a caregiver.

BTACT Test Completion Codes

To characterize the feasibility of administering the BTACT in our cohort, a Test Completion Code (developed for this project; Table 2) was assigned to each BTACT subtest. In addition to providing information about logistical and other barriers to subtest completion, the codes allow imputation of the lowest or worst possible scores when data are missing not due to logistical or other reasons but rather due to severity of cognitive impairment preventing subtest completion.23–25

Table 2.

Test Completion Codes

| Code | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Test administered in full, results are valid | Objective performance score is obtained. |

| Test Attempted but NOT Completed Due to: | ||

| 2* | Severity of cognitive deficits | Severity of cognitive impairment, receptive or expressive language impairment preclude completion of the test. This code is also used if it is clear that a participant's refusal to continue is due to their cognitive/neurological problems (e.g., frustration resulting from perceived failure, etc.). |

| 3 | Physical/non-cognitive reasons | Pre-existing hearing problems, physical pain |

| 4 | Refusal | Refusal to continue which does not appear to be due to failure on test times or cognitive impairment precluding ability to continue |

| 5 | Non-English or Spanish speaking patient | Limited English language skills preclude valid testing |

| 6 | Logistical reasons, other reasons | This includes scheduling problems, threats to validity (noise, interruptions), etc. |

| Test NOT Attempted due to: | ||

| 7* | Severity of cognitive deficits | Cognitive impairment, receptive or expressive language impairment. This code is also used if it is clear that a participant's refusal to participate is due to their cognitive/neurological problems (e.g., poor performances on items administered). |

| 8 | Physical/non cognitive reasons | Pre-existing hearing problems, physical pain |

| 9 | Refusal | Participant refuses to attempt the test |

| 10 | Non-English or Spanish Speaking Patient | Limited English language skills preclude valid testing, |

| 11 | Logistical Reasons, Other Reasons | This includes scheduling problems, threats to validity (noise, interruptions), etc. |

| 12 | Unknown | Reasons for noncompletion are unknown; this code includes cases who expired. |

Low scores can be imputed for subtests with missing data due to severity of cognitive impariment.

BTACT Data Collector Survey

The BTACT Data Collector Survey was designed by study investigators to qualitatively evaluate data collectors' experience administering the BTACT over the phone to individuals with moderate-severe TBI. The online survey consisted of yes/no and open-ended questions regarding the logistics and feasibility of the BTACT overall and for each individual subtest.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample demographics. We calculated a BTACT composite score13,16 by deriving a z-score for each of five subtests (the Red/Green test is not included in this composite) based on the mean and the standard deviation (SD) of the overall MIDUS II Cognitive Project sample,14 and then averaged and re-standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) these five z-scores to produce a composite z-score.13,16 We calculated standardized scores for each subtest by age decade, education, and gender based on the MIDUS II Cognitive Study sample.14

We performed descriptive analyses (percentiles, mean, SD, range) to describe the completion rates and administration times among the different BTACT subtests. We used correlations to evaluate the relationships between the BTACT summary scores, FIM Cognition subscale scores (FIM Cog), and GOSE; we used paired t-tests to evaluate changes in BTACT scores between time-points. For these analyses, we used worst-score imputation for BTACT subtests among individuals who were unable to provide performance scores due to severity of cognitive impairment, based on noncompletion codes.23 All quantitative analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software26 or Stata.27 We tabulated responses from the BTACT Data Collector Survey and grouped the responses by feasibility question and by BTACT subtest, as appropriate.

Results

A total sample of 463 individuals participated in the study at Year 1, and 386 participated at Year 2 post-injury. Of the individuals who participated at Year 1, 81.0% also participated during the Year 2 follow-up, and 11 participants were newly recruited at Year 2. The demographic characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 3. Participants with missing data were standardized using only their known demographic variables. At Year 1, one participant was missing data on gender, one had missing data on age, and 34 participants had unknown level of education. At Year 2, 45 participants had missing data on education.

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample at 1 and 2 Years Post-Injury

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 463 | 386 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 336 (72.7) | 275 (71.2) |

| Female | 126 (27.3) | 111 (28.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 273 (59.2) | 224 (59.4) |

| Black | 87 (18.9) | 73 (19.4) |

| Hispanic | 80 (17.35) | 63 (16.7) |

| Other | 21 (4.56) | 17 (4.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), year | 47.9 (20.9) | 47.1 (20.2) |

| Age at injury, mean (SD), year | 46.9 (20.9) | 45.4 (20.2) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Greater than high school | 75 (16.4) | 54 (14.4) |

| High school/GED | 168 (36.7) | 145 (38.8) |

| Less than high school | 215 (46.9) | 175 (46.8) |

| Injury Severity based on GCS, n (%) | ||

| GCS 13–15 | 171 (42.1) | 127 (38.7) |

| GCS 9–12 | 50 (12.3) | 38 (11.6) |

| GCS 3–8 | 185 (45.6) | 163 (49.7) |

| Injury Severity based on PTA, n (%) | ||

| PTA <1 day | 45 (10.0) | 31 (8.3) |

| PTA 1 − 7 days | 76 (16.8) | 61 (16.3) |

| PTA >7 days | 331 (73.2) | 281 (75.4) |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; PTA, post-traumatic amnesia.

We found that a majority of individuals in our sample were able to provide a valid performance score on the BTACT. Subtest completion rates of the full sample ranged from 60.5% to 68.7% and 56.2% to 64.2% for Years 1 and 2, respectively. Of the participants who independently completed the standard TBIMS follow-up assessments (as opposed to completion through proxy) in Year 1 (60.3%) and Year 2 (59.8%), completion rates for the BTACT subtests ranged from 82.3% to 88.3% (Table 4).

Table 4.

BTACT Subtest Completion Rates at 1 and 2 Years Post-Injury

| Completion rates of the full Sample | Completion rates among those who independently completed other follow-up assessments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1, % | Year 2, % | Year 1, % | Year 2, % | |

| (n = 463) | (n = 386) | (n = 279) | (n = 231) | |

| Word Recall | 68.7 | 64.2 | 88.2 | 87.9 |

| Backward Digit Span | 67.2 | 64.0 | 88.2 | 87.9 |

| Category Fluency | 67.0 | 64.2 | 87.8 | 88.3 |

| Red Green | 60.5 | 57.3 | 82.8 | 82.3 |

| Reasoning | 61.8 | 56.2 | 84.6 | 82.3 |

| Backward Counting | 66.1 | 61.1 | 87.1 | 85.3 |

| Delayed Word Recall | 65.0 | 60.6 | 86.4 | 85.7 |

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone.

We calculated subtest and total administration times (which include the examiner reading and repeating the instructions, plus participant response time) only for those subjects who were able to complete each subtest (Table 5). Total administration time for the full BTACT battery was approximately 16 min.

Table 5.

BTACT Administration Times (in Seconds) by Subtest

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |

| Word Recall | 313 | 102.9 (44.8) | 248 | 99.5 (40.1) |

| Backward Digit Span | 307 | 121.6 (58.3) | 247 | 113.1 (59.0) |

| Category Fluency | 306 | 89.6 (28.5) | 248 | 88.7 (26.1) |

| Red Green | 275 | 303.1 (104.4) | 221 | 313.1 (89.0) |

| Reasoning | 281 | 231.0 (116.8) | 217 | 231.9 (98.4) |

| Backward Counting | 302 | 49.8 (19.7) | 236 | 47.1 (16.8) |

| Delayed Word Recall | 297 | 61.2 (26.1) | 234 | 61.9 (23.9) |

| Total (Sum of Subtests; minutes) | 266 | 16.2 (4.2) | 210 | 16.2 (3.2) |

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone.

Reasons for non-completion varied only slightly across subtests and study time-points; the most common reasons included severity of cognitive deficits, refusal, and logistical/other reasons. Completion codes for each subtest by study time-point are presented in Table 6. We also explored whether there were any systematic differences between those who were able to complete the BTACT and those who were unable due to reasons other than cognitive impairment using independent samples t-tests; the only significant difference we found between these groups was on the FIM Cognitive subtest [Year 1 t(111.0) = 2.2, Year 2, t(96.5) = 2.8)]; we found no differences between these groups on GOS-E or duration of PTA.

Table 6.

BTACT Subtest Completion Codes at 1 and 2 Years Post-Injury

| Year 1, % (n = 463) | Year 2, % (n = 386) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word Recall | Backward Digits | Category Fluency | Red Green | Reasoning | Backward Counting | Word Recall Delay | Word Recall | Backward Digits | Category Fluency | Red Green | Reasoning | Backward Counting | Word Recall Delay | |

| Test administered in full- results valid | 68.7 | 67.2 | 67.0 | 60.5 | 61.8 | 66.1 | 65.0 | 64.2 | 64.0 | 64.2 | 57.3 | 56.2 | 61.1 | 60.6 |

| Test attempted but not completed due to: | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| Severity of cognitive deficits | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Non-neurological physical reasons | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Refusal to continue | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Non-English speaking | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Logistical reasons/other reasons | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Test not attempted due to: | 24.6 | 25.7 | 25.7 | 28.1 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 27.4 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 28.2 | 31.6 | 28.5 | 28.2 |

| Severity of cognitive deficits | 6.9 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Non-neurologic/ physical reasons | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Refusal | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 11.9 | 11.7 |

| Non-English speaking | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Logistical reasons/other reasons | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 |

| Unknown/Missing | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone.

Next, we explored whether the BTACT composite score demonstrated expected associations with other variables in the TBIMS National Database, including injury severity as defined by duration of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), employment status at the concurrent time-point (Table 7), and the Cognitive subscale of the FIM and GOSE (Table 8). In the BTACT composite score analyses, individuals who were unable to complete a given subtest due to severity of cognitive deficits were assigned the lowest possible score (zero) on that subtest, per previous protocols.23

Table 7.

Year 1 and Year 2 BTACT Composite Score by Duration of PTA and Employment Status

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |

| PTA <1 day | 27 | −0.13 (1.81) | 15 | 0.01 (1.80) |

| PTA 1 − 7 days | 55 | −0.42 (1.88) | 45 | −0.38 (1.45) |

| PTA >7 days | 250 | −1.65 (2.01) | 190 | −1.40 (2.01) |

| Total | 332 | −1.33 (2.05) | 250 | −1.13 (1.96) |

| Employed or studying | 103 | −0.46 (1.53) | 91 | −0.22 (1.37) |

| Unemployed | 233 | −1.67 (2.13) | 157 | −1.60 (2.05) |

| Total | 336 | −1.30 (2.04) | 248 | −1.09 (1.94) |

The BTACT composite scores are based on participants who were able to provide valid performance scores or were unable to complete a given subtest due to severity of cognitive deficits. The BTACT composite score has a mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1.

PTA, post-traumatic amnesia; BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone.

Table 8.

Pearson Correlations of BTACT Composite Score with FIM Cognitive Subscale and GOS-E at Year 1 and Year 2

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | FIM cognitive | GOS-E | n | FIM cognitive | GOS-E | |

| BTACT Composite Score | 336 | 0.498** | 0.401** | 243 | 0.601** | 0.531** |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; GOS-E, Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended.

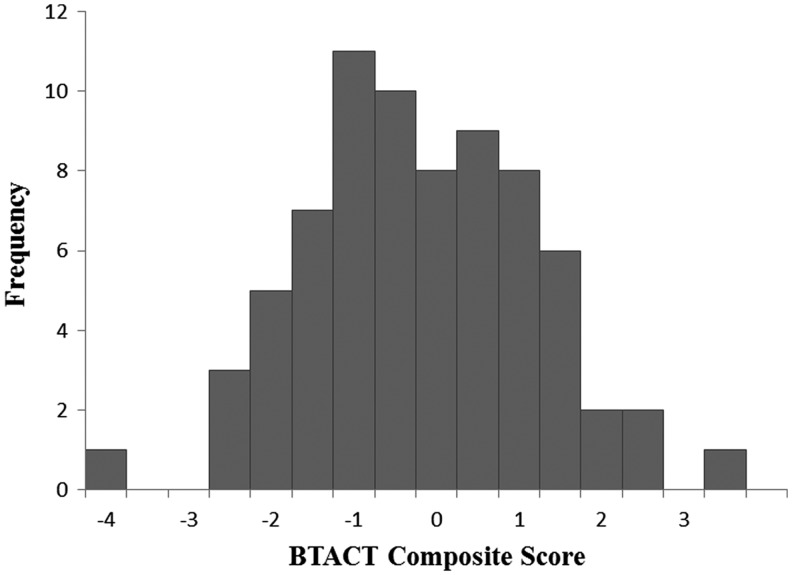

We further explored associations of the BTACT with the Cognitive subscale of the FIM, which is collected via structured interview from the participant or proxy informant (as opposed to a performance test requiring involvement of the participant). As seen in Table 9, there was general correspondence between the measures, as indicated by a graded increase in BTACT composite scores across levels of the FIM Cognitive scale. We noticed the expected ceiling effects of the FIM7,28,29 in our sample (Table 9), so we evaluated the distribution of BTACT scores among those at the ceiling of the FIM and found a normally distributed range of scores (Fig. 1). We found similar distributions of BTACT scores at each level of the FIM Cognitive scale (data not shown), suggesting the BTACT provides a more granular evaluation of cognition across the spectrum of functioning.

Table 9.

BTACT Composite Score within Each FIM Cognitive Level

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |

| 1 | 6 | −4.54 (1.42) | 3 | −5.12 (1.26) |

| 2 | 11 | −3.24 (2.51) | 3 | −4.42 (1.08) |

| 3 | 15 | −3.68 (1.33) | 6 | −3.90 (2.47) |

| 4 | 33 | −2.57 (2.61) | 19 | −3.02 (1.71) |

| 5 | 47 | −1.53 (2.05) | 42 | −2.11 (1.70) |

| 6 | 151 | −0.84 (1.63) | 130 | −0.42 (1.51) |

| 7 | 73 | −0.44 (1.41) | 40 | −0.19 (1.38) |

| Total | 336 | −1.29 (2.03) | 243 | −1.07 (1.94) |

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone; FIM Cognitive, Functional Independence Measure Cognition.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT) composite score at ceiling on Functional Independence Measure Cognitive score during Year 1 (FIM® Cog Level 7).

Finally, we evaluated whether the BTACT and any of its subscales were able to detect changes in performance between Years 1 and 2. We used worst-score imputation for individuals who were unable to provide performance scores due to severity of cognitive impairment based on noncompletion codes.23 Results are presented in Table 10 and demonstrate statistically significant change, with small effect sizes, for the BTACT composite score and for the Reasoning subtest. We also looked at patterns of noncompletion codes and found change over this interval in ability to complete the test itself; specifically, 7% of the sample that participated in both time-points could complete more BTACT subtests at Year 2 than they were able to (due to severity of cognitive impairment) at Year 1, and nearly 5% of the sample could complete fewer BTACT subtests at Year 2.

Table 10.

Change from Year 1 to Year 2 in the BTACT Composite Score and Subtests

| Change from year 1–year 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| t | p | Effect size | |

| BTACT Composite Score | 2.36 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Word Recall | 1.21 | ns | 0.08 |

| Backward Digits | 0.03 | ns | 0.00 |

| Category Fluency | 0.48 | ns | 0.03 |

| Red Green Normal | 1.19 | ns | 0.08 |

| Reasoning | 3.11 | <.01 | 0.21 |

| Backward Counting | 1.11 | ns | 0.07 |

| Delayed Word Recall | 0.89 | ns | 0.06 |

BTACT, Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone.

As described above, additional information about feasibility and ease of use of the BTACT were gathered via survey from the data collectors. Seventeen data collectors across participating centers completed the survey, which took approximately 25 min to complete. In response to open-ended questions asking if the battery was liked or disliked, they reported that administering the BTACT on the phone was feasible, efficient, and enjoyable for the data collectors and participants alike. While the order of the first (Word List) and last (Word List Delayed Recall) subtests were never altered, per standardized instructions, a minority of the data collectors (3/17) reported occasionally altering the order of tests, whether for logistical reasons (e.g., time constraints) or to offer an easier test (e.g., backward counting) earlier in the battery for participants who expressed frustration. Data collectors reported additional benefits of the BTACT in open-ended responses; these included ease of administration and scoring, the variable content which participants found engaging, and the general nature of the battery which does not require travel for in-person study visits.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate it is feasible to administer a brief cognitive assessment over the telephone to individuals with clinically significant TBI. A considerable majority of participants in the current study were able to complete the BTACT at 1 and 2 years post-injury, yielding objective data on a wide variety of cognitive domains in a relatively brief period of time. The psychometric properties of the BTACT are described in detail elsewhere6 and results from the current study demonstrate expected relationships between the test summary scores and indices of injury severity and functional outcome. The BTACT clearly provides more granular information about cognitive functioning than the FIM, which is among the most commonly used TBI outcome measures. Importantly, results of the current study suggest the BTACT is able to detect changes over time during a period after the most rapid spontaneous recovery may have passed; however, it should be noted that simple change scores are not ideal for describing change that is not uniform, as is seen here with some participants becoming able to complete the test who were previously unable, and vice versa.

There are limitations to this study that should be considered. The TBIMS is comprised of specialized centers for TBI inpatient rehabilitation, and thus, our findings may not generalize individuals with TBI who are treated at other centers or who do not receive inpatient rehabilitation. The BTACT was implemented in the TBIMS where participants have committed to data collection and interviewers undergo rigorous training in standardized assessment, which may have contributed to the high test completion and low refusal rates reported here.

The availability of a feasible, well-tolerated, and psychometrically sound telephone-based cognitive test battery has exciting implications for TBI research. The TBIMS is the largest prospective TBI outcome study in the world, having enrolled over 15,000 participants with excellent retention rates for up to 25 years of telephone-based longitudinal follow-up, and the addition of a cognitive test battery will expand the knowledge gained through this and other similarly designed research studies.30 Cognitive deficits are nearly universal among individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI, and often underlie and exacerbate limitations in day-to-day functioning, particularly as survivors of TBI age. Some evidence suggests that some individuals experience improvement many years after TBI while others begin to decline; overall, however, very little is known about long-term cognitive outcomes after TBI.31 The risk of neurodegenerative disorders such as dementia is a growing concern among patients and their families, although the evidence of an association between TBI and accelerated cognitive aging remains mixed.32 A brief telephone-based cognitive test may serve several other important functions in TBI research, such as providing a way to classify patients for clinical trial participation to reduce sample heterogeneity,33 or as an outcome measure for clinical trials.34 Much remains to be learned about the ways in which TBI impacts cognitive functioning over time, and results of the current study suggest the BTACT may facilitate advancements in this important area of study.35 More broadly, it is widely recognized that many people experiencing major trauma are treated at centers distant from their homes, which increases the challenge of essential follow-up after discharge. A phone-based cognitive assessment provides a feasible way of monitoring an important component of recovery without the need for transport to a specialized facility. It is expected that this will become increasing important as emphasis on telehealth expands.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Sandra Caldwell, Andrea Gagliano, Letty Ginsburg, Kara Jodry, Jamie Kaminski, Brendan Kelley, Devon Kratchman, Christian Lucca, Melissa Mayes, Caron Morita, Joseph Ostrow, Rebecca Runkel, Krista Smith, Dennis Tirri, Denise Vasquez, Peter Waselkov, Erica Wasmund, and Gabrielle Guetta for their contributions to data collection for this study.

This work was funded by Grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research to the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data and Statistical Center (Grant Number is 90DP0010), the New York TBI Model System (Grant Number 90DP0038), Indiana University/Rehabilitation Hospital of Indiana TBI Model System (Grant Number 90DP0036), University of Washington Traumatic Brain Injury Model System (Grant Number 90DP0031), Spaulding-Harvard TBI Model System (Grant Number 90DP0039), University of Alabama at Birmingham Traumatic Brain Injury Care System (Grant Number 90DP0044), Moss TBI Model System (Grant Number 90DP0037), Rocky Mountain Regional Brain Injury System (Grant Number 90DP0034), Northern New Jersey Traumatic Brain Injury System (Grant Number 90DP0032), South Florida TBI Model System (Grant Number 90DP0046).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Whyte J., Ponsford J., Watanabe T., and Hart T. (2010). Traumatic brain injury, in: Delisa's Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice, Frontera W.R., (ed). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, pps. 575–623 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. (1997). Guide for the Uniform Data Set For Medical Rehabilitation (including the FIM™ Instrument), version 5.1. State University of New York at Buffalo: Buffalo, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heiden J.S., Small R., Caton W., Weiss M., and Kurze T. (1983). Severe head injury. Clinical assessment and outcome. Phys. Ther. 63, 1946–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennett B., Snoek J., Bond M.R., and Brooks N. (1981). Disability after severe head injury: observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 44, 285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin H.S., Boake C., Song J., McCauley S., Contant C., Diaz-Marchan P., Brundage S., Goodman H., and Kotrla K.J. (2001). Validity and sensitivity to change of the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 18, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigan J.D., Cuthbert J.P., Harrison-Felix C., Whiteneck G.G., Bell J.M., Miller A.C., Coronado V.G., and Pretz C.R. (2014). US population estimates of health and social outcomes 5 years after rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, E1–E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pretz C.R. and Dams-O'Connor K. (2013). Longitudinal description of the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended for individuals in the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database: a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94, 2486–2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pretz C.R., Kozlowski A.J., Dams-O'Connor K., Kreider S., Cuthbert J.P., Corrigan J.D., Heinemann A.W., and Whiteneck G. (2013). Descriptive modeling of longitudinal outcome measures in traumatic brain injury: a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94, 579–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrigan J.D., and Hammond F.M. (2013). Traumatic brain injury as a chronic health condition. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94, 1199–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane P.K., Gibbons L.E., McCurry S.M., McCormick W., Bowen J.D., Sonnen J., Keene C.D., Grabowski T., Montine T.J., and Larson E.B. (2016). Importance of home study visit capacity in dementia studies. Alzheimers Dement. 12, 419–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castanho T.C., Amorim L., Zihl J., Palha J.A., Sousa N., and Santos N.C. (2014). Telephone-based screening tools for mild cognitive impairment and dementia in aging studies: a review of validated instruments. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tun P.A. and Lachman M.E. (2006). Telephone assessment of cognitive function in adulthood: the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone. Age Ageing 35, 629–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brim O., Ryff C., and Kessler R. (2004). The MIDUS national survey: an overview, in: How Healthy Are We? A National Study of Well-Being at Midlife. O. Brim C. Ryff R. Kessler (eds). The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, pps. 1–36 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryff C., and Lachman M. (2013). Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2): cognitive project, 2004–2006. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research Ann Arbor, MI: Available at: 10.3886/ICPSR25281.v5 Accesed July 26, 2017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2012). Common data elements: traumatic brain injury. Available at: www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/TBI.aspx#tab=Data_Standards Accessed July26, 2017

- 16.Lachman M.E., Agrigoroaei S., Tun P.A., and Weaver S.L. (2014). Monitoring cognitive functioning: psychometric properties of the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone. Assessment 21, 404–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachman M.E., and Tun P.A. (2011). Brief Test of Adult Cognition By Telephone (BTACT) with stop & go switch task (SGST). Available at: www.brandeis.edu/departments/psych/lachman/pdfs/btact%20forms%20and%20information%204.9.12.pdf Accessed July26, 2017

- 18.Rey A. (1964). L'Examen Clinique en Psychologie. Presses Universitaires de France: Paris [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor E.M. (1959). Psychological Appraisal of Children With Cerebral Defects. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wechsler D.A. (1997). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrigan J.D., Smith-Knapp K., and Granger C.V. (1997). Validity of the Functional Independence Measure for Persons with traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 78, 828–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson J.T., Pettigrew L.E., and Teasdale G.M. (1998). Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J. Neurotrauma 15, 573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagiella E., Novack T.A., Ansel B., Diaz-Arrastia R., Dikmen S., Hart T., and Temkin N. (2010). Measuring outcome in traumatic brain injury treatment trials: recommendations from the Traumatic Brain Injury Clinical Trials Network. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 25, 375–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haltiner A.M., Temkin N.R., Winn H.R., and Dikmen S.S. (1996). The impact of posttraumatic seizures on 1-year neuropsychological and psychosocial outcome of head injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2, 494–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikmen S., Machamer J., Temkin N., and McLean A. (1990). Neuropsychological recovery in patients with moderate to severe head injury: 2 year follow-up. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 12, 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IBM Corp. (2013). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 22.0. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.StataCorp (2017). Stata statistical software: release 15. StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rezaei S., Dehnadi Moghadam A., Khodadadi N., and Rahmatpour P. (2015). Functional Independence Measure in Iran: a confirmatory factor analysis and evaluation of ceiling and floor effects in traumatic brain injury patients. Arch. Trauma Res. 4, e25363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson O.D., Gabbe B.J., Sutherland A.M., Wolfe R., Forbes A.B., and Cameron P.A. (2011). Comparing the responsiveness of functional outcome assessment measures for trauma registries. J. Trauma 71, 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dijkers M.P., Harrison-Felix C., and Marwitz J.H. (2010). The Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems: history and contributions to clinical service and research. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 25, 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millis S.R., Rosenthal M., Novack T.A., Sherer M., Nick T.G., Kreutzer J.S., High W.M., Jr, and Ricker J.H. (2001). Long-term neuropsychological outcome after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 16, 343–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dams-O'Connor K., Guetta G., Hahn-Ketter A.E., and Fedor A. (2016). Traumatic brain injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: current knowledge and future directions. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 6, 417–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saatman K.E., Duhaime A.C., Bullock R., Maas A.I., Valadka A., and Manley G.T. (2008). Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J. Neurotrauma 25, 719–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg N.D., Crane P.K., Dams-O'Connor K., Holdnack J., Ivins B.J., Lange R.T., Manley G.T., McCrea M., and Iverson G.L. (2017). Developing a cognition endpoint for traumatic brain injury clinical trials. J. Neurotrauma 34, 363–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fjell A.M. and Walhovd K.B. (2010). Structural brain changes in aging: courses, causes and cognitive consequences. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 187–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]