Summary:

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells play a crucial role in orchestrating the humoral arm of adaptive immune responses. Mature Tfh cells localize to follicles in secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) where they provide help to B cells in germinal centers (GCs) to facilitate immunoglobulin affinity maturation, class switch recombination, and generation of long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells. Beyond the canonical GC Tfh cells, it has been increasingly appreciated that the Tfh phenotype is highly diverse and dynamic. As naïve CD4+ T cells progressively differentiate into Tfh cells, they migrate through a variety of microanatomical locations to obtain signals from other cell types, which in turn alters their phenotypic and functional profiles. We herein review the heterogeneity of Tfh cells marked by the dynamic phenotypic changes accompanying their developmental program. Focusing on the various locations where Tfh and Tfh-like cells are found, we highlight their diverse states of differentiation. Recognition of Tfh cell heterogeneity has important implications for understanding the nature of T helper cell identity specification, especially the plasticity of the Tfh cells and their ontogeny as related to conventional T helper subsets.

Keywords: T follicular helper cells, germinal center, T cell differentiation, T cell migration

Introduction

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells that specialize in helping B cells to produce antibodies in the face of antigenic challenge. Tfh cells have the unique ability to migrate into follicles in secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) where they co-localize with B cells to deliver contact-dependent and soluble signals that support survival and differentiation of the latter cells. Interactions between Tfh and B cells initially begin outside the follicle, before continuing therein in the germinal center (GC), a microanatomical structure where proliferating antigen-specific B cells undergo immunoglobulin affinity maturation, class switch recombination, and differentiation into long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells. In addition to the generation and maintenance of the GC reaction, Tfh cells are essential for the extrafollicular antibody response, which gives rise to an early wave of short-lived antibody-producing plasmablasts and memory B cells (1–3). Therefore, Tfh cells are essential to the generation of short- and long-lived humoral immunity, necessary for the protective response against a wide range of pathogens.

Although their emergence accompanies that of the canonical T helper (Th) subsets, Th1, Th2, and Th17, effector Tfh cells generally do not express the lineage-defining transcription factors of these other Th subsets, such as T-bet, Gata3, and RORγt, which are required for their respective development. By contrast, the transcriptional factor B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl6) selectively regulates Tfh cell differentiation, as Bcl6 expression promotes the effector Tfh phenotype (4–6). Bcl6-deficiency abolishes Tfh cell development with little effect on other Th-cell subsets, a finding leading to the recognition of Bcl6 as the Tfh cell master transcription factor (4–6). Additional transcription factors were later found to positively regulate Tfh cell development, including achaete-scute homolog 2 (Ascl2), T cell factor-1 (TCF-1), lymphoid enhancer-binding factor-1 (LEF-1), proposed to be upstream Bcl6 expression, and interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) (7–9). These transcription factors drive the expression of a series of molecules important for Tfh cell development and maintenance, localization to the B-cell follicle, and function therein, including inducible costimulator (ICOS), the G-protein coupled 7-transmembrane receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CXCR5), and programed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), respectively, all of which also serve as canonical Tfh-cell markers, along with interleukin-21 (IL-21), driven by the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and necessary for B cell maturation.

The ability of Tfh cells to enter B cell follicles is conferred by the coordinated regulation of an array of gradient-sensing cell surface receptors, most notably CXCR5, the first identified surface marker of Tfh cells (10). CXCR5 senses and drives migration towards its ligand CXC-chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13), produced by follicular stromal cells (11). In addition to upregulating CXCR5 needed for follicular entry, Tfh cells downregulate the T cell zone homing chemokine receptor CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7), the ligands of which are CC-chemokine ligand 19 (CCL19) and CCL21 secreted by high endothelial venules (HEVs) in lymph nodes and fibroblastic reticular cells in the T cell zone (12, 13), P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), which enhances chemotaxis towards CCL19 and CCL21 (14–16), and spinghosince-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1), which senses S1P abundantly found in blood and lymph. The repression of these receptors prevents the egress of developing Tfh cells from the SLO and pushes developing cells from the T cell zone into the center of the follicles where CCL19, CCL21, and S1P expression is low.

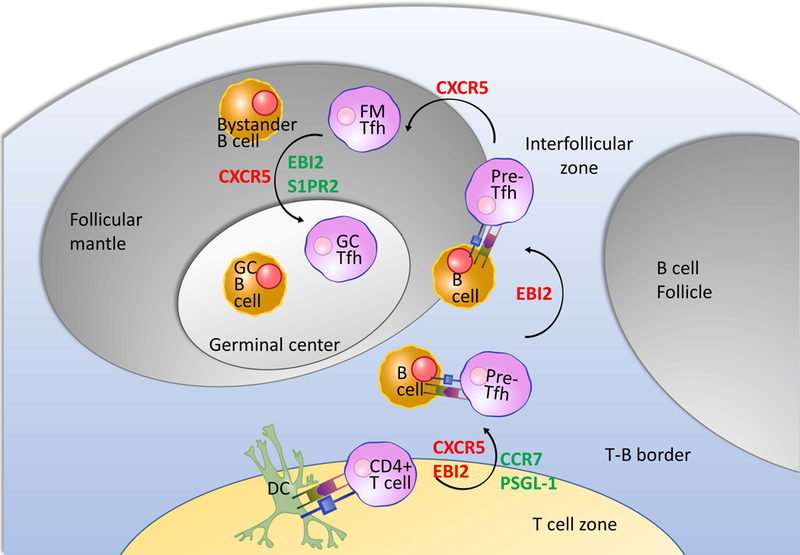

While primarily characterized by their localization in the follicle, Tfh cells are highly dynamic and motile. They migrate through multiple microanatomical locations where the microenvironment, be it the chemokine concentration or the mixtures of signals delivered by cells encountered at that location, have an effect on cellular differentiation and phenotype of Tfh cells (Figure 1). Therefore, analysis of Tfh cells in homogenized tissue samples offers a snapshot of an amalgamation of cells at different stages in their complex and dynamic developmental process. This review highlights the high degree of heterogeneity generated during Tfh-cell development, with special focus on spatial distribution and cell-cell interaction as related to cellular differentiation and function.

Figure 1. Migration and cell-cell interaction in Tfh cell development.

Naïve CD4+ T cells are primed by antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs) with co-stimulatory signals at the edge of the T cell zone where they develop the pre-Tfh phenotype (Bcl6lo/int CXCR5int PD-1int). These newly emergent pre-Tfh cells receive a second round of stimulation from cognate B cells at the T cell zone- B cell follicle border/interfollicular (IF) zone. This interaction cements the Tfh cell differentiation program with mature Tfh cells migrating into the follicle. Tfh cells that robustly express the canonical Tfh markers (including CXCR5, PD-1, Bcl6, and IL-21) are found in the germinal center (GC) at the follicular center interacting with GC B cells, whereas follicular mantle Tfh cells receiving signals from bystander B cells that line the follicular parenchyma exhibit the pre-Tfh phenotype. Changes in expression of surface receptors responsible for guiding Tfh cell localization are shown in red for upregulation, and green for downregulation. Arrows in this graph illustrate a phenotype-centric view of the multiple stages of Tfh cell development, from the least to the most polarized expression profile of Tfh-associated molecules, not necessarily the temporal order. Illustrations of cells and molecules were obtained from Reactome Icon Library https://reactome.org/icon-lib (134).

At beginning: Tfh cells develop in the outer T cell zone of secondary lymphoid organs

Tfh-cell differentiation is initiated when naïve CD4+ T cells in the T cell zone of SLOs encounter activated antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs). During this first stage of differentiation, T cells receive antigen stimulation through their T cell receptor (TCR) in combination with co-stimulation from DCs and specific cytokines. If these requirements are met, priming by DCs alone is sufficient to induce an early pre-Tfh cell phenotype. CD4+ T cells activated by DCs initiate Bcl6 transcription within hours with detectable levels of Bcl6 protein expression at first cell division before rapidly gaining expression of the canonical surface markers CXCR5, PD-1, and ICOS (17, 18). The early pre-Tfh cell phenotype is also governed by the transcription factor ASCL2, which binds the Cxcr5 locus to directly upregulate CXCR5 and downregulate expression of CCR7 and PSGL-1 in a Bcl6-independent manner (7).

As is the case for other effector CD4+ T cell subsets, Tfh lineage specific differentiation depends largely on the distinct cytokine milieu present in the T zone. In mice, Tfh cell development relies on IL-6 and IL-21 signaling through the transcription factor STAT3, with loss of either cytokine impairing cell differentiation (19–21). IL-6 is produced by DCs upon sensing microbial signals, by follicular B cells, and by non-hematopoietic cells, possibly stromal cells (22–25). IL-6 signaling then induces IL-21 production in T cells, which signals in an autocrine manner to further promote IL-21 expression (19, 21, 26). The transcription factors TCF-1 and LEF-1 promote Tfh cell fate in part by upregulating IL-6 receptor and thus increasing the responsiveness to IL-6 (9). In humans, IL-12, IL-6, and TGFβ have been implicated in Tfh cell development. Activated human DCs produce IL-12, which upregulates Bcl6, CXCR5, and ICOS expression in co-cultured T cells in a STAT4-dependent manner (27, 28). Unlike mouse Tfh cells, in which development is inhibited by TGFβ (29), human TGFβ is found to synergize with IL-12 and IL-23, which also signals through STAT4, to enhance STAT3-STAT4 signaling and promote Tfh cell differentiation (30). Another prominent player in Tfh cell differentiation is IL-2, which signals through STAT5 and potently inhibits Tfh cell development (31–33). Phosphorylated STAT5 inhibits STAT3 binding to the Bcl6 locus and instead enhances the expression of the transcription factor B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1) (31, 33, 34). Blimp-1 then antagonizes Bcl6, thus driving T cell differentiation towards other non-Tfh effector subsets. In support of the antagonistic role of IL-2, it has recently been reported that Tfh cells come from a population of IL-2-secretors that signals in a paracrine manner to repress Tfh cell fate in non-IL-2 producers, while driving Blimp-1 expression in T cells destined for Th1 cell fate choice (18).

In addition to cytokine production, a fraction of DCs also display an array of co-stimulatory molecules to promote Tfh cell differentiation. The IRF4-dependent migratory DC subset, known as migratory conventional DC (cDC) 2, has been found to be both necessary and sufficient for initiation of the Tfh cell developmental program (35–38). Upon activation, this subset of DCs migrates to the outer edge of T zone, possibly through their preferential expression of CXCR5 and Epstein-Barr virus-induced G-protein coupled receptor 2 (EBI2, also known as G-protein coupled receptor 183, GPR183), where they colocalize with CD4+ T cells and express high levels of co-stimulatory molecules ICOS ligand (ICOSL) and OX40 ligand (OX40L), and the IL-2 receptor alpha chain CD25 (35, 37–39). While CD25 is proposed to quench surrounding IL-2 to promote Tfh cell differentiation (37), ICOS-ICOSL and OX40-OX40L interactions both favor Tfh cell development through activation of PI3K and Akt signaling (40–44).

As their developmental program is initiated, pre-Tfh cells also undergo metabolic reprogramming, presumably to adapt to the future environment in which they will reside. Unlike most other effector T cells which switch to a glycolytic program when activated (45–47), Tfh cells are found to be more reliant on mitochondrial oxidation, as Bcl6 expression alone is sufficient for repression of glycolysis-related genes (31, 48). The lack of IL-2 signaling in pre-Tfh and Tfh cells may also favor their metabolic program with low glycolytic activity, as high affinity IL-2 signaling through CD25 activates the PI3K-Akt-mTORc1 axis to promote glycolysis (48). Indeed, Tfh cells are found to have lower mTOR activity and shRNA knockdown of mTOR or mTORc1 in T cells favors the generation of Tfh cells (48). However, a low level of mTOR signaling is required for Tfh cell development, as genetic ablation of mTOR results in deficient Tfh cell differentiation (49, 50). This distinct mode of metabolic reprogramming may stem from the need for fully differentiated Tfh cells to survive in the GC, where glucose may become limiting due to the extensive proliferation undergone by GC B cells. By switching on an oxidative metabolic program, differentiating Tfh cells might be able to inhabit a unique niche in nutrient consumption and survive in a relatively nutrient-deficient environment.

Next stop: Tfh cells at T-B cell border

Although the Tfh cell developmental program is initiated during priming by DCs, maintenance of Tfh phenotypes and full maturation largely rely on B cells. DC-priming induced increase in CXCR5 and PD-1 expression does not indicate fate-commitment but rather marks a global activation state, with the majority of antigen-specific T cells exhibit a pre-Tfh phenotype immediately after activation but fail to maintain the phenotype as the response progresses (51). As this early wave of activated pre-Tfh cells upregulate CXCR5 and EBI2 and downregulate CCR7 and PSGL-1, they migrate towards the T zone-B cell follicle border (37, 51, 52). The T-B border marks the location for initial cognate T-B cell interaction, as antigen-engaged B cells also accumulate there due to their upregulation of CCR7 after activation, enabling migration toward CCL19 and CCL21 in the T cell zone (53). Upon class II MHC-antigen presentation by B cells to their cognate T helper cells, they together form motile conjugates that maintain stable contact for minutes to hours (54, 55). When T cell help is delivered across the synapse in the form of CD40L, B cells upregulate EBI2 expression (56). This guides T-B conjugates to migrate along the T-B border into the interfollicular (IF) regions of lymph nodes near the perimeter of the follicle, where more rounds of proliferation occur (51, 57). Therefore, cognate interactions are important not only for proper positioning of T and B cells but also for their subsequent clonal expansion.

Reciprocal signals from cognate B cells delivered across the stable synapse are required for pre-Tfh cells to develop into effector Tfh cells and have been suggested to determine which pre-Tfh cells can complete their differentiation. In cell transfer systems in which TCR-transgenic T cells are adoptively transferred with or without their cognate BCR-transgenic B cells into recipient mice, cognate B cells are required for further induction of Bcl6 expression in pre-Tfh cells to sustain the Tfh phenotype, robust recruitment into the follicle, and later development into CXCR5hi PD-1hi GC Tfh cells (17, 51, 57). In addition to integrins, formation of long-lasting synapses between T and B cells requires the adaptor signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM)-associated protein (SAP), which binds SLAM family receptors Ly108 and CD84 (55, 58). SAP-deficient pre-Tfh cells fail to further proliferate after encountering B cells and later have defects in recruitment and retention in the GC (55, 58). The developmental requirement for B cells can be lifted when antigens are abundantly available, in setting such as repeated antigen injection and chronic infections (59, 60).

Tfh Cells in the B Cell Follicle

Once Tfh cells initiate follicular entry, an event believed to occur mainly through CXCR5-mediated chemotaxis up the CXCL13 gradient (61), they interact with bystander B cells which line the follicular parenchyma. These transient non-cognate interactions are crucial for follicular retention of Tfh cells and the occurrence of the subsequent GC reaction (60, 62). Bystander B cells express ICOSL constitutively at a level comparable to DCs, and when interacting with Tfh cells, induce ICOS signaling in Tfh cells (62). ICOS signaling in Tfh cells further induces CXCR5 and suppresses CCR7, PSGL-1, and CD62L (also known as L-selectin) expression through the transcription factor KLF2 (36, 63) and promotes cell motility in a PI3K-dependent manner (62), such that they respond robustly to CXCL13 and migrate further into the follicle. Although cognate B cells express ICOSL at a higher level compared to bystander B cells, cognate interactions are most likely rare during Tfh entry into the follicle. This is simply due to the low frequency of antigen-specific B cells, whereas the density of naïve B cells on the outer edge of follicles may compensate for lower ICOSL expression on individual cells. In fact, the requirement for ICOSL on cognate B cell can be bypassed entirely, unless under conditions in which antigen presentation by B cells is limiting (57).

In addition to the activating signal ICOSL, bystander B cells also express PD-L1, ligand for PD-1, which is thought to provide suppressive signal to follicular entry by activated T cells (64). While ICOS-expressing T cells can be recruited into the follicle regardless of PD-L1 expression on bystander B cells, follicular entry of non-ICOS-expressing cells is inhibited by PD-L1 (64). Negative regulation of Tfh cell development imposed by PD-L1 on bystander B cells is thus proposed to be the reason why continuous ICOS signaling is required for the maintenance of Tfh phenotype and follicular localization, as well as a mechanism for recruitment of exclusively ICOS-high expressing cells into the follicle (64).

Germinal Center Tfh Cells

As GCs form inside the central follicular region, follicular Tfh cells can be further divided into two subsets based on their localization, GC and follicular mantle (FM). In vivo photolabeling experiments revealed that compared to their FM counterparts, GC Tfh cells express higher levels of CXCR5 and PD-1 on their cell surface (65) and more canonical Tfh-associated molecules such as Bcl6, IL-21, IL-4, and Maf at the transcript level (66). Although both FM and GC subsets are motile, the FM-GC segregation of Tfh cells is relatively stable. Less than one third of GC Tfh cells migrate to its surrounding FM or to an adjacent follicle within the span of 24 hours, whereas roughly twenty percent of FM Tfh cells enter the GC in the same timeframe (65, 66).

Localization to the GC has been found to be guided by EBI2 and S1PR2, with the former being downregulated in GC Tfh cells and GC B cells while the latter is upregulated (66, 67). Overexpression of EBI2 in Tfh cells suppresses GC entry, whereas EBI2-deficient Tfh cells show increased confinement inside the GC (66). On the other hand, S1PR2-deficient Tfh cells fail retention in the GC, while GC Tfh cells that arrived at the FM-GC interface fail to return to inside the GC (67). The previously mentioned SLAM family signaling adaptor SAP has also been implicated to have a role in GC retention of follicular Tfh cells, as SAP is more highly expressed in GC Tfh cells at transcript level and SAP-deficient cells found at the FM-GC interface more frequently migrate to the FM instead of entering the GC compared to wildtype Tfh cells (55, 66). However, the mechanism underlying SAP-guided GC localization remains mostly unknown.

The spatial segregation of Tfh cells in the follicle may also be regulated by factors provided by surrounding B cells. GC B cells robustly express plexin B (PlxnB), which interacts with its binding partner semaphorin 4C (Sema4C) that is upregulated by GC Tfh cells (68). This interaction promotes adhesion and entanglement between GC Tfh and B cells and is thought to guide Sema4C-expressing Tfh cells for retention in the PlxnB-rich GC (68). In contrast, ephrin B1 (EFNB1) on GC B cells, signaling through Ephrin type-B receptor 6 (EPHB6) on the T cells, inhibits adhesion with GC Tfh cells, which in turn limit GC retention of Tfh cells (69). In addition to GC B cells, bystander B cells may also provide signals that govern GC localization of Tfh cells. For instance, a lack of PD-L1 expression on bystander B cells and defective PD-1 upregulation in T cells both result in reduced GC to FM Tfh ratio, suggesting a role of PD-1 signaling in GC positioning of Tfh cells (64).

Although the functional role of FM Tfh cells remains largely unknown due to limitations in identification and isolation strategies based on spatial distribution, the contribution of GC Tfh cells to humoral response has been well described. Most notably, GC Tfh cells deliver contact-dependent and soluble signals during the GC reaction, which give rise to antibody class-switching and affinity maturation, as well as differentiation of long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells. These help signals include co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40L and ICOS and cytokines such as IL-21, IL-4, and interferon gamma (IFN-γ). It is important to note that these help signals are utilized not only by GC Tfh cells, but also by extrafollicular T cells that share characteristics of Tfh cells (16, 70). These extrafollicular B cell helpers promote the generation of short-lived plasmablasts and are described in detail in another review in this same issue (71, 72).

Delivered across the synapse by GC Tfh cells, CD40L signaling through CD40 is crucial for survival and maintenance of GC B cells. Genetic deletion of CD40L results in defect in GC formation and lack of class-switched antibody production, while blockage of CD40-CD40L interaction using antibodies ablates pre-established GCs (73–75). Synaptic delivery of CD40L occurs rapidly and selectively, as GC Tfh cells form brief yet extensive contacts with antigen-presenting GC B cells in a process named serial entanglement (76). High affinity GC B cells presenting antigen form large areas of contact with GC Tfh cells, which induces transient calcium flux in the latter cells (76). Intracellular calcium signaling, enhanced further by ICOS-ICOSL interaction between GC Tfh and B cells, promote rapid externalization of CD40L from intracellular storage and B cell acquisition of T help (77). CD40 signaling in turn upregulates ICOSL expression on GC B cells, thus creating an intercellular feed forward loop that ensures the maximal acquisition of positive signals by selected GC B cells (77). In human Tfh cells, dopamine secretion across the immunological synapse enhances B-cell surface expression of ICOSL, leading to enhanced formation of dopamine-storing chromogranin B granules and CD40L externalization at the synapse with an increase in its area and heightened T-B cell collaboration (78).

Calcium flux in GC Tfh cells also leads to enhanced expression of IL-21 and IL-4, cytokines important for Tfh effector functions (76, 79, 80). The canonical Tfh cytokine IL-21 regulates the GC response by maintaining Bcl6 expression in GC B cells and is thus critical for GC persistence, function, and output (81, 82). In addition, IL-21 promotes B cell proliferation and differentiation into antibody secreting cells both in vitro and in vivo (83–85). IL-4, on the other hand, was recognized first as a cytokine with anti-apoptotic effect on B cells through STAT6-dependent induction of the Bcl-2 family member transcription factor Bcl-extra large (Bcl-xL) and upregulation of glycolytic metabolic processes (86–88). Aside from its role in promoting survival of B cells, IL-4 supports isotype switching to murine IgG1 in type 2 responses, in contrast to IFN-γ, which helps class switching to murine IgG2 in type 1 responses (89).

In addition to the aforementioned positive regulatory signals, the inhibitory molecule PD-1 also plays an essential role in the generation of optimal GC responses. Induced by TCR signaling, PD-1 is expressed at a high level in GC Tfh cells, which forms repeated contact with GC B cells that express its ligand PD-L1 and PD-L2 (90). Deletion of PD-1 and PD-L1/L2 result in expansion in the Tfh cell compartment accompanied by reduced expression of IL-21 and IL-4 which lead to defects in GC output, including decreased GC B cell survival and impairment in memory B cell and plasma cell generation (90, 91).

Subsets of GC Tfh Cells

Given the variety of help signals delivered by Tfh cells, it comes as no surprise that GC Tfh cells are functionally heterogeneous. As the humoral arm of the response needs to correspond to the nature of pathogen challenge, Tfh cells are closely related to the effector Th cells in a given response. For instance, GC Tfh cells can produce the signature cytokines of their corresponding Th effectors, such as IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 (4, 92, 93). Sorted IL-21-producing Tfh cells also can be repolarized ex vivo to secrete Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines (94). This great degree of plasticity in cytokine secretion allows Tfh cells to promote GC B cells to class switch to the isotype appropriate for the type of infection, be it IFN-γ-driven generation of inflammatory IgG2a/c (IgG1 in human) in response to intracellular pathogen, or IL-4-driven induction of IgG1 (IgG4 in human) and IgE for clearance of helminths. In addition to exerting functions in the GC, Th cell cytokine production by GC Tfh cells also hint at a common developmental program shared by these subsets of CD4+ T cells. This notion is further supported by epigenetic studies in sorted Tfh cells that revealed positive chromatin marks on Th1 and Th2 lineage-determining transcription factor loci Tbx21 (which encodes T-bet) and Gata3 (94).

The developmental link between Tfh cells and their Th cell counterparts is well-documented in type 1 responses, where Th1 development is initiated when type I IFN and IL-12 activate STAT1 and STAT4 to promote T-bet and IFN-γ expression (95–97) (Figure 2). In addition to T-bet and IFN-γ, STAT4 also induces expression of Bcl6 and IL-21 in early Th1 cells (98, 99). A population of early Tfh cells also co-express IFN-γ and IL-21 and have similar level of T-bet expression as Th1 cells (99). This subset of Tfh cells has been confirmed by fate-tracking experiments, which further demonstrated that Tfh cells that previously expressed T-bet become IFN-γ-producing GC Tfh cells (100). IFN-γ production by Tfh cells is dependent on STAT4 signaling, which presumably leads to T-bet-dependent and -independent chromatin remodeling at the Ifng locus to retain accessibility even after T-bet expression in lost (99, 100). In type 1 infection settings such as influenza and Plasmodium chabaudi, a population of IFN-γ and IL-21 double producing T cells confer protection in part through facilitating humoral immunity yet are able to retain their cytokine production profile even in the absence of Bcl6 (101, 102). Despite the suggested importance of IFN-γ and IL-21 double producers, it remains unclear how these cells are functionally distinct from IFN-γ and IL-21 single producers, as are the potentially different effects of the same cytokine(s) delivered by Th1 cells and Tfh cells.

Figure 2. Bifurcation of conventional T helper and Tfh cell differentiation in type 1 immune responses.

Upon dendritic cell (DC) priming, the majority of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells upregulate Bcl6 expression. Cognate interaction with B cells (not shown in figure) maintains Bcl6 expression and supports maturation of Tfh cells. A fraction produces interferon-γ (IFN-γ); such cells initially upregulate the transcription factor T-bet, then downregulate its expression albeit with continuation of open chromatin at the Ifng gene locus, Both Th1 and Tfh cells co-express T-bet and Bcl6 early following immune challenge, and produce both IFN-γ and IL-21. Secretion of both cytokines by Tfh cells promotes GC B cell development and selection, as well as switching to the major effector isotype (IgG2 in mice, IgG1 in humans) in type 1 responses. On the other hand, Th1 cells produce the canonical cytokine IFN-γ to activate killing of intracellular pathogens by macrophages. Illustrations of cells and molecules were obtained from Reactome Icon Library https://reactome.org/icon-lib (134).

On the other hand, GC Tfh cells in type 2 responses has long been described to express IL-4 (92, 103) (Figure 3). The extent of Tfh heterogeneity is further exemplified using an IL-4/IL-21 double reporter system in which Tfh cells can be found expressing any combination of the two cytokines in the GC (104). Analysis of Tfh cells in each cell division and in adoptive transfer systems reveals that during developmental progression, IL-21-expressing Tfh cells, which emerge early in the response, switch to IL-4 expression after their encounter with antigen-presenting GC B cells (76, 104). At any given time, a mixture of Tfh cells at various stages of development (determined by cytokine reporter expression) can be observed participating in the GC response, thus creating a heterogenous pool of effectors that contribute to different aspects of the response. In addition to being transcriptionally distinct, Tfh cells at early and late stages of development differ in helper function, as assessed by adoptive transfer into recipient mice bearing an irrelevant TCR transgene enabling selective evaluation of the functional effect of transferred Tfh cells. IL-21-expressing Tfh cells are the most robust driver of affinity maturation upon adoptive transfer, promoting high-affinity somatic hypermutation of an IgH variable region in GC B cells. In contrast, IL-4-expressing Tfh cells generate more isotype-switched GC B cells and antibody-secreting cells by inducing B cell expression of Blimp-1, presumably in part through their enhanced CD40L expression compared to the IL-21 producing Tfh cell subset (104). These experiments highlight the functional significance of cytokines delivered specifically by Tfh cells in the absence of a disrupted immune response, which allows an increased appreciation for the functions of Tfh-associated cytokines in established GCs. With IL-21 crucial for maintaining GC B cell identity and IL-4 for B cell survival (81, 82, 86–88), the multitude of cytokine functions may be overlooked in experiments using genetic knockout animals. These functional subsets of Tfh cells are also differentially distributed throughout the GC, with IL-4-expressing Tfh cells being the farthest from the GC dark zone due to their low levels of CXCR4 expression (104). However, the significance of the differential localization of various GC Tfh subsets remains unclear.

Figure 3. Functional and transcriptional changes of Tfh cells in type 2 responses.

Whereas Th2 cells produce IL-4 to activate helminth clearance mediated by basophils, mast cells, and eosinophils (not shown), GC Tfh cells in a type 2 response upregulate IL-21 production early in the response before switching to IL-4 secretion. IL-21-producing Tfh cells are effective drivers of affinity maturation, while IL-4 producing Tfh promotes B cell differentiation into antibody secreting cells and class switch recombination into isotypes found in type 2 responses. This shift in GC Tfh cell functionality hints at a mechanism by which temporal regulation cytokine availability fine-tunes the GC output, suggesting that allergic responses to innocuous antigens may be driven by a later stage GC with predominantly IL-4-producing Tfh cells that promote IgE production. Illustrations of cells and molecules were obtained from Reactome Icon Library https://reactome.org/icon-lib (134).

Another site where heterogeneity could be generated is in gut Peyer’s patches. Unlike other lymphoid tissues, Peyer’s patches continuously harbor active GC in response to the microbiota to generate protective and regulatory IgA antibodies. Because of this unique property, GCs in the gut could harbor Tfh cells originated from effector regulatory T cells (Treg) and Th17 subsets, a phenomenon that has not been described in other lymphoid tissues (105, 106). Using fate-tracking of Treg and Th17 cells from lymph nodes and spleens in an adoptive transfer model, it has been shown that transferred cells that home to the Peyer’s patches in the gut can become GC Tfh cells. In support of these observations, depletion of Treg and Th17 cells both result in defect in IgA responses (106, 107). Although these results remain somewhat controversial, they raise interesting implications regarding the ontogeny of normal gut Tfh cells and perhaps the degree of autoreactivity permitted at various sites of the body. Another intersection between Tfh and Treg cell identity is the subset of thymic-derived Treg cells found in the follicle and GC of mice and humans known as follicular regulatory T cells (Tfr) (108, 109). With their co-expression of Bcl6 and the Treg lineage-defining transcriptional factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3), Tfr cells modulate the GC response through suppression mechanisms such as secretion of IL-10 and contact-dependent signals (108–111). A detailed review of Tfr cell differentiation and functions is in another article in this same issue.

Tfh Cells in the Blood

After the initial identification of Tfh cells in the follicles in human tonsils, effort has been devoted to finding the counterparts of follicular Tfh cells in human blood due to its greater accessibility that facilitates analysis. Since then, subsets of CD4+ T cells with “Tfh-like” characteristics, frequently referred to as circulating Tfh (cTfh) cells, have been identified in peripheral blood of humans and mice. Although their exact origin and relation to Tfh cells in SLOs remain unclear, the frequency of various cTfh subsets has been correlated with vaccine responses and disease activities in chronic infection and autoimmunity. Administration of influenza vaccine induces increase of a CXCR3+ population of cTfh cells that correlates with increase in high-avidity antibodies (112, 113). Induction of cTfh cells has also been observed in volunteers receiving in-trial HIV vaccines and a novel Escherichia coli vaccine (114–116). Patients with autoimmunity such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren syndrome have increased number of cTfh cells with an “activated” phenotype which correlates with disease activity (117–121). In HIV-infected individuals, frequency of CXCR3- cTfh cells correlate with the generation of broadly neutralizing antibody (122).

Despite sharing common characteristics with bona fide Tfh cells, cTfh cells generally lack expression of canonical Tfh markers. Compared to Tfh cells in SLOs, cTfh cells express CXCR5, PD-1, ICOS at low to intermediate amounts, without detectable Bcl6 (117–119, 123). Yet, like tissue Tfh cells, cTfh cells are effective B cell helpers, presumably due to their secretion of cytokines such as IL-21, IL-10, and IL-2 (123, 124) in concert with their CXCR5-dictated follicular homing capability.

The cTfh compartment is heterogenous. Based on CXCR3 and CCR6 expression, cTfh cells can be divided into CXCR3+ Th1-like, CXCR3- CCR6- Th2-like, and CXCR3- CCR6+ Th17-like subsets. Whereas the CXCR3- subsets of cTfh cells can induce differentiation of naïve B cells into antibody-secreting cells, the CXCR3+ compartment is found to correlate with the avidity of influenza-specific antibody post vaccination and thus has been suggested to promote expansion of high-avidity antibody-secreting cells through an extrafollicular process (112, 123). In addition to chemokine receptor expression, cTfh cells can also be divided into “activated” and “resting” subsets based on PD-1 expression, with the PD-1hi “activated” population most efficiently promoting B cell differentiation into antibody-secreting cells with IgG production (118, 122). This PD-1hi versus PD-1lo categorization also corresponds to the differentiation kinetics of cTfh cells. The early population of cTfh, characterized by a PD-1hi CCR7lo phenotype, is seen in peripheral blood of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis patients and in conventional immune responses, around day 7 post vaccination in humans and mice, which suggest correspondence to active Tfh cell differentiation in the SLOs (118). In contrast, the PD-1lo CCR7hi subset, identified as memory-like cTfh cells, are found in blood at 21 days post vaccination and may persist into the memory compartment (118).

Memory T Cells with Tfh Cell Potential

The idea that the cTfh population may include cells that constitute part of the CD4+ T memory pool is supported mainly by the observation that they include antigen-experienced and long-lived cells that express markers of central memory populations (125). Indeed it has been demonstrated that Tfh cells in murine secondary lymphoid tissues have the capability of differentiating into recirculating memory cells (126–129). A fraction of these memory cells expresses CXCR5, the primary marker for identifying cTfh cells, and resides primarily in blood and secondary lymphoid tissues, consistent with their central memory phenotype (125). Therefore, the enhanced helper function of blood borne cTfh cells has been suggested to be due to a recall of a previously committed cell fate (130).

As some CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells have a central memory T cell phenotype with expression of CCR7 and CD62L (CCR7+ CD62L+) and reside in secondary lymphoid tissues, bone marrow, and blood, they possibly localize to the T-B cell border, balance CCR7- and CXCR5-driven chemotaxis, with recirculation in and out of the bone marrow for growth factor stimulation, such as via IL-7 and IL-15 (129, 131). This idea is supported by the finding that memory CD4+ T cells are found on the outer edge of the follicle where they presumably sample antigens displayed on subcapsular sinus (SCS) macrophages, while awaiting antigen recognition to be reactivated (66). Adoptive transfer experiments have also demonstrated that CXCR5+ memory CD4+ T cells more readily differentiate into Tfh cells in a secondary response even in the absence of B cells, suggesting that they have previously committed to the Tfh cell lineage (125). This finding also indicates that B cells are not required as antigen presenting cells in the recall response, supporting the hypothesis of antigen acquisition at the SCS. After reactivation, secondary Tfh cells promote differentiation of antibody-secreting cells and the formation of secondary GCs to re-diversify the B cell receptors (132). A similar population of antigen-experienced cells was recently described in human tonsils as PSGL-1hi CXCR5hi PD-1hi and was found at the T-B border colocalizing with memory B cells, suggesting their role in memory B cell reactivation upon antigenic recall (133).

Despite the increased interest in the functional role of Tfh-like memory cells, their exact origin is incompletely known. It has been shown repeatedly in adoptive transfer studies of cells expressing Tfh cell surface molecules (CXCR5hi PD-1hi PSGL-1lo Ly6clo) and the canonical Tfh cell cytokine IL-21 (using an IL-21 reporter) that mature GC Tfh cells do not undergo global apoptosis during cell contraction following immune challenge, and can persist into the memory phase (127–129). Animal studies that disrupt normal Tfh cell development using animals absent Bcl6 in T cells or ICOSL in the B cell compartment also showed that defective Tfh cell development leads to abolished CXCR5+ memory cells (129). However, more recently, the GC phase of Tfh cell differentiation has been suggested to be dispensable, as SAP-deficient human and mice both have normal frequencies of CXCR5+ T memory cells (118). Furthermore, adoptive transfer studies that attempted to subset Tfh populations have found that a population similar to pre-Tfh cells that express intermediate levels of Th1 and Tfh markers (CXCR5intermidate (int), PD-1int,Ly6clo, T-betint) possesses the most central memory potential (126, 128, 129). Fate-tracking using a tamoxifen-inducible Ccr7-Cre-ERT2 mouse suggested that this population contained cells that upregulated CCR7 during the height of the adaptive immune response and was able to persist into memory phase (129). However, given the graded expression of CCR7 in CD4+ T cells, further specification of the precursor population has been proven to be difficult.

Perhaps another approach to probing the determinants of CXCR5+ T memory cell generation includes accepting Th versus Tfh differentiation as a continuum (Figure 4). The two ends of this continuum are marked by tissue-homing effector Th and GC Tfh cells, the subset most specialized in their corresponding helper function. In between the two architypes are differentiated cells that have varied degrees of Th and Tfh cell characteristics which may not exist in distinct subsets. Rather than further dividing this population and comparing their ability to become memory cells, an approach that focuses on identifying the factors that diminish the memory potential in the two ends may yield more useful information in regards to the developmental requirements of CXCR5+ memory T cells.

Figure 4. Model of Tfh memory formation in type 1 responses.

Upon activation, naïve CD4+ T cells initiate bifurcating differentiation down a Waddingtonian landscape (illustration of CD4+ T cell differentiation landscape adapted from Rebhahn et al. (135)). As they receive signals that facilitate progress through their developmental programs, their phenotype becomes increasingly polarized in the direction of Th1 or Tfh. This polarization, however, is a gradual and graded process that does not result in two completely distinct populations, but rather a phenotypic continuum (shown as the expression of canonical Tfh markers PD-1 and CXCR5). Previous studies have shown that compared to Th1 and Tfh cells, CD4+ T cells with a less polarized phenotype generally have a greater potential to persist into the memory pool. This phenotypically identified memory precursor population could contain CD4+ T cells at an earlier stage of differentiation (such as pre-Tfh cells) or mature effectors that express intermediate levels of canonical subset markers (such as non-GC Tfh cells).

Conclusion

Since the recognition of Tfh cells as a distinct subset with unique functions different from that of conventional Th cells, much has been learned about their development and importance in health and diseases. Recent developments in the understanding of Tfh cell heterogeneity reveal the dynamic nature of this cell population, their ontogenetic link with other Th effector subsets, and the various aspects of their function. These revelations raised fundamental questions about Tfh cell biology. What other location-specific signals influence development and phenotype? What are the relative contributions of direct signals and stochasticity in the bifurcation of Tfh and conventional Th cell development and the degree of heterogeneity that exists between these polarized states? How does spatiotemporally regulated delivery of a handful of Tfh help molecules generate the wide range of outcomes in B cell fate? What is the nature of Tfh cell memory and how is it generated? Is the degree of heterogeneity among Tfh cells high enough such that the relative functional contribution of each subgroup can be parsed out? If so, is it possible to therapeutically target a pathogenic subgroup of Tfh cells without gravely affecting protective Tfh-driven responses? Much remains to be understood about these fundamental processes. With the increased recognition of the functional importance of Tfh cells in humoral immunity and protection against pathogens and in generation of autoimmunity, it is crucial to further elucidate answers to these fundamental questions.

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by NIH grants R37 AR40072, R01 AR068994, R61 AR073948, and the Lupus Research Alliance. The authors also acknowledge the helpful discussions with colleagues at Yale University. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Di Niro R, Lee SJ, Vander Heiden JA, et al. Salmonella Infection Drives Promiscuous B Cell Activation Followed by Extrafollicular Affinity Maturation. Immunity. 2015;43:120–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson EB, Caporale LH, Thorbecke GJ. Effect of thymus cell injections on germinal center formation in lymphoid tissues of nude (thymusless) mice. Cell Immunol. 1974;13:416–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchison NA. T-cell-B-cell cooperation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu D, Rao S, Tsai LM, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Chen X, Zhong B, et al. Transcription factor achaete-scute homologue 2 initiates follicular T-helper-cell development. Nature. 2014;507:513–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollig N, Brustle A, Kellner K, et al. Transcription factor IRF4 determines germinal center formation through follicular T-helper cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8664–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi YS, Gullicksrud JA, Xing S, et al. LEF-1 and TCF-1 orchestrate T(FH) differentiation by regulating differentiation circuits upstream of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:980–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1553–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunn MD, Ngo VN, Ansel KM, Ekland EH, Cyster JG, Williams LT. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt’s lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luther SA, Bidgol A, Hargreaves DC, et al. Differing activities of homeostatic chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 in lymphocyte and dendritic cell recruitment and lymphoid neogenesis. J Immunol. 2002;169:424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagira M, Imai T, Yoshida R, et al. A lymphocyte-specific CC chemokine, secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC), is a highly efficient chemoattractant for B cells and activated T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veerman KM, Williams MJ, Uchimura K, et al. Interaction of the selectin ligand PSGL-1 with chemokines CCL21 and CCL19 facilitates efficient homing of T cells to secondary lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poholek AC, Hansen K, Hernandez SG, et al. In vivo regulation of Bcl6 and T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 2010;185:313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odegard JM, Marks BR, DiPlacido LD, et al. ICOS-dependent extrafollicular helper T cells elicit IgG production via IL-21 in systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2873–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumjohann D, Okada T, Ansel KM. Cutting Edge: Distinct waves of BCL6 expression during T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 2011;187:2089–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiToro D, Winstead CJ, Pham D, et al. Differential IL-2 expression defines developmental fates of follicular versus nonfollicular helper T cells. Science. 2018;361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eddahri F, Denanglaire S, Bureau F, et al. Interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling regulates the ability of naive T cells to acquire B-cell help capacities. Blood. 2009;113:2426–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cucak H, Yrlid U, Reizis B, Kalinke U, Johansson-Lindbom B. Type I interferon signaling in dendritic cells stimulates the development of lymph-node-resident T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2009;31:491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodge IL, Carr MW, Cernadas M, Brenner MB. IL-6 production by pulmonary dendritic cells impedes Th1 immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:4457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karnowski A, Chevrier S, Belz GT, et al. B and T cells collaborate in antiviral responses via IL-6, IL-21, and transcriptional activator and coactivator, Oct2 and OBF-1. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2049–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Ma W, Zhang T, Wu L, Qi H. Phenotypic Tfh development promoted by CXCR5-controlled re-localization and IL-6 from radiation-resistant cells. Protein Cell. 2015;6:825–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suto A, Kashiwakuma D, Kagami S, et al. Development and characterization of IL-21-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma CS, Suryani S, Avery DT, et al. Early commitment of naive human CD4(+) T cells to the T follicular helper (T(FH)) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31:158–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarron MJ, Marie JC. TGF-beta prevents T follicular helper cell accumulation and B cell autoreactivity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4375–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt N, Liu Y, Bentebibel SE, et al. The cytokine TGF-beta co-opts signaling via STAT3-STAT4 to promote the differentiation of human TFH cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:856–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oestreich KJ, Read KA, Gilbertson SE, et al. Bcl-6 directly represses the gene program of the glycolysis pathway. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:957–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballesteros-Tato A, Leon B, Graf BA, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurieva RI, Podd A, Chen Y, et al. STAT5 protein negatively regulates T follicular helper (Tfh) cell generation and function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11234–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calabro S, Liu D, Gallman A, et al. Differential Intrasplenic Migration of Dendritic Cell Subsets Tailors Adaptive Immunity. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2472–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi YS, Kageyama R, Eto D, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Lu E, Yi T, Cyster JG. EBI2 augments Tfh cell fate by promoting interaction with IL2-quenching dendritic cells. Nature. 2016;533:110–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin C, Han JA, Koh H, et al. CD8alpha(−) Dendritic Cells Induce Antigen-Specific T Follicular Helper Cells Generating Efficient Humoral Immune Responses. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1929–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnaswamy JK, Gowthaman U, Zhang B, et al. Migratory CD11b(+) conventional dendritic cells induce T follicular helper cell-dependent antibody responses. Sci Immunol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gigoux M, Shang J, Pak Y, et al. Inducible costimulator promotes helper T-cell differentiation through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20371–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacquemin C, Schmitt N, Contin-Bordes C, et al. OX40 Ligand Contributes to Human Lupus Pathogenesis by Promoting T Follicular Helper Response. Immunity. 2015;42:1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.So T, Choi H, Croft M. OX40 complexes with phosphoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase B (PKB) to augment TCR-dependent PKB signaling. J Immunol. 2011;186:3547–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song J, So T, Cheng M, Tang X, Croft M. Sustained survivin expression from OX40 costimulatory signals drives T cell clonal expansion. Immunity. 2005;22:621–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao N, Eto D, Elly C, Peng G, Crotty S, Liu YC. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch is required for the differentiation of follicular helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:657–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frauwirth KA, Riley JL, Harris MH, et al. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16:769–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macintyre AN, Gerriets VA, Nichols AG, et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab. 2014;20:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2011;35:871–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ray JP, Staron MM, Shyer JA, et al. The Interleukin-2-mTORc1 Kinase Axis Defines the Signaling, Differentiation, and Metabolism of T Helper 1 and Follicular B Helper T Cells. Immunity. 2015;43:690–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J, Lin X, Pan Y, et al. Critical roles of mTOR Complex 1 and 2 for T follicular helper cell differentiation and germinal center responses. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng H, Cohen S, Guy C, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 Kinase Signaling and Glucose Metabolism Drive Follicular Helper T Cell Differentiation. Immunity. 2016;45:540–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kerfoot SM, Yaari G, Patel JR, et al. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity. 2011;34:947–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coffey F, Alabyev B, Manser T. Initial clonal expansion of germinal center B cells takes place at the perimeter of follicles. Immunity. 2009;30:599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reif K, Ekland EH, Ohl L, et al. Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature. 2002;416:94–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okada T, Miller MJ, Parker I, et al. Antigen-engaged B cells undergo chemotaxis toward the T zone and form motile conjugates with helper T cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi H, Cannons JL, Klauschen F, Schwartzberg PL, Germain RN. SAP-controlled T-B cell interactions underlie germinal centre formation. Nature. 2008;455:764–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly LM, Pereira JP, Yi T, Xu Y, Cyster JG. EBI2 guides serial movements of activated B cells and ligand activity is detectable in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues. J Immunol. 2011;187:3026–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinstein JS, Bertino SA, Hernandez SG, et al. B cells in T follicular helper cell development and function: separable roles in delivery of ICOS ligand and antigen. J Immunol. 2014;192:3166–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cannons JL, Qi H, Lu KT, et al. Optimal germinal center responses require a multistage T cell:B cell adhesion process involving integrins, SLAM-associated protein, and CD84. Immunity. 2010;32:253–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fahey LM, Wilson EB, Elsaesser H, Fistonich CD, McGavern DB, Brooks DG. Viral persistence redirects CD4 T cell differentiation toward T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:987–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deenick EK, Chan A, Ma CS, et al. Follicular helper T cell differentiation requires continuous antigen presentation that is independent of unique B cell signaling. Immunity. 2010;33:241–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ansel KM, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Ngo VN, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Cyster JG. In vivo-activated CD4 T cells upregulate CXC chemokine receptor 5 and reprogram their response to lymphoid chemokines. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1123–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu H, Li X, Liu D, et al. Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystander B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature. 2013;496:523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber JP, Fuhrmann F, Feist RK, et al. ICOS maintains the T follicular helper cell phenotype by down-regulating Kruppel-like factor 2. J Exp Med. 2015;212:217–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi J, Hou S, Fang Q, Liu X, Liu X, Qi H. PD-1 Controls Follicular T Helper Cell Positioning and Function. Immunity. 2018;49:264–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shulman Z, Gitlin AD, Targ S, et al. T follicular helper cell dynamics in germinal centers. Science. 2013;341:673–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suan D, Nguyen A, Moran I, et al. T follicular helper cells have distinct modes of migration and molecular signatures in naive and memory immune responses. Immunity. 2015;42:704–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moriyama S, Takahashi N, Green JA, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 is critical for follicular helper T cell retention in germinal centers. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yan H, Wu L, Shih C, et al. Plexin B2 and Semaphorin 4C Guide T Cell Recruitment and Function in the Germinal Center. Cell Rep. 2017;19:995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu P, Shih C, Qi H. Ephrin B1-mediated repulsion and signaling control germinal center T cell territoriality and function. Science. 2017;356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cunningham AF, Serre K, Mohr E, Khan M, Toellner KM. Loss of CD154 impairs the Th2 extrafollicular plasma cell response but not early T cell proliferation and interleukin-4 induction. Immunology. 2004;113:187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.MacLennan IC, Toellner KM, Cunningham AF, et al. Extrafollicular antibody responses. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qi H T follicular helper cells in space-time. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:612–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han S, Hathcock K, Zheng B, Kepler TB, Hodes R, Kelsoe G. Cellular interaction in germinal centers. Roles of CD40 ligand and B7–2 in established germinal centers. J Immunol. 1995;155:556–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu J, Foy TM, Laman JD, et al. Mice deficient for the CD40 ligand. Immunity. 1994;1:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Foy TM, Laman JD, Ledbetter JA, Aruffo A, Claassen E, Noelle RJ. gp39-CD40 interactions are essential for germinal center formation and the development of B cell memory. J Exp Med. 1994;180:157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shulman Z, Gitlin AD, Weinstein JS, et al. Dynamic signaling by T follicular helper cells during germinal center B cell selection. Science. 2014;345:1058–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu D, Xu H, Shih C, et al. T-B-cell entanglement and ICOSL-driven feed-forward regulation of germinal centre reaction. Nature. 2015;517:214–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Papa I, Saliba D, Ponzoni M, et al. TFH-derived dopamine accelerates productive synapses in germinal centres. Nature. 2017;547:318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agarwal S, Avni O, Rao A. Cell-type-restricted binding of the transcription factor NFAT to a distal IL-4 enhancer in vivo. Immunity. 2000;12:643–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim HP, Korn LL, Gamero AM, Leonard WJ. Calcium-dependent activation of interleukin-21 gene expression in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linterman MA, Beaton L, Yu D, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med. 2010;207:353–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zotos D, Coquet JM, Zhang Y, et al. IL-21 regulates germinal center B cell differentiation and proliferation through a B cell-intrinsic mechanism. J Exp Med. 2010;207:365–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ettinger R, Kuchen S, Lipsky PE. The role of IL-21 in regulating B-cell function in health and disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:60–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Feng CG, et al. A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production. Science. 2002;298:1630–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Good KL, Bryant VL, Tangye SG. Kinetics of human B cell behavior and amplification of proliferative responses following stimulation with IL-21. J Immunol. 2006;177:5236–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dufort FJ, Bleiman BF, Gumina MR, et al. Cutting edge: IL-4-mediated protection of primary B lymphocytes from apoptosis via Stat6-dependent regulation of glycolytic metabolism. J Immunol. 2007;179:4953–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wurster AL, Rodgers VL, White MF, Rothstein TL, Grusby MJ. Interleukin-4-mediated protection of primary B cells from apoptosis through Stat6-dependent up-regulation of Bcl-xL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Paul WE, Ohara J. B-cell stimulatory factor-1/interleukin 4. Annu Rev Immunol. 1987;5:429–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Toellner KM, Luther SA, Sze DM, et al. T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 characteristics start to develop during T cell priming and are associated with an immediate ability to induce immunoglobulin class switching. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Good-Jacobson KL, Szumilas CG, Chen L, Sharpe AH, Tomayko MM, Shlomchik MJ. PD-1 regulates germinal center B cell survival and the formation and affinity of long-lived plasma cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:535–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawamoto S, Tran TH, Maruya M, et al. The inhibitory receptor PD-1 regulates IgA selection and bacterial composition in the gut. Science. 2012;336:485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, et al. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu KT, Kanno Y, Cannons JL, et al. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Afkarian M, Sedy JR, Yang J, et al. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mullen AC, High FA, Hutchins AS, et al. Role of T-bet in commitment of TH1 cells before IL-12-dependent selection. Science. 2001;292:1907–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu J, Jankovic D, Oler AJ, et al. The transcription factor T-bet is induced by multiple pathways and prevents an endogenous Th2 cell program during Th1 cell responses. Immunity. 2012;37:660–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nakayamada S, Kanno Y, Takahashi H, et al. Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity. 2011;35:919–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weinstein JS, Laidlaw BJ, Lu Y, et al. STAT4 and T-bet control follicular helper T cell development in viral infections. J Exp Med. 2018;215:337–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fang D, Cui K, Mao K, et al. Transient T-bet expression functionally specifies a distinct T follicular helper subset. J Exp Med. 2018:2705–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carpio VH, Opata MM, Montañez ME, Banerjee PP, Dent AL, Stephens R. IFN-γ and IL-21 Double Producing T Cells Are Bcl6-Independent and Survive into the Memory Phase in Plasmodium chabaudi Infection. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyauchi K, Sugimoto-Ishige A, Harada Y, et al. Protective neutralizing influenza antibody response in the absence of T follicular helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liang HE, Reinhardt RL, Bando JK, Sullivan BM, Ho IC, Locksley RM. Divergent expression patterns of IL-4 and IL-13 define unique functions in allergic immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;13:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weinstein JS, Herman EI, Lainez B, et al. TFH cells progressively differentiate to regulate the germinal center response. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hirota K, Turner JE, Villa M, et al. Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer’s patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsuji M, Komatsu N, Kawamoto S, et al. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science. 2009;323:1488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17:983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, et al. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. 2011;17:975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wollenberg I, Agua-Doce A, Hernandez A, et al. Regulation of the germinal center reaction by Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Laidlaw BJ, Lu Y, Amezquita RA, et al. Interleukin-10 from CD4(+) follicular regulatory T cells promotes the germinal center response. Sci Immunol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bentebibel S-E, Khurana S, Schmitt N, et al. ICOS(+)PD-1(+)CXCR3(+) T follicular helper cells contribute to the generation of high-avidity antibodies following influenza vaccination. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:26494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Koutsakos M, Wheatley AK, Loh L, et al. Circulating TFH cells, serological memory, and tissue compartmentalization shape human influenza-specific B cell immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cardeno A, Magnusson MK, Quiding-Jarbrink M, Lundgren A. Activated T follicular helper-like cells are released into blood after oral vaccination and correlate with vaccine specific mucosal B-cell memory. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Heit A, Schmitz F, Gerdts S, et al. Vaccination establishes clonal relatives of germinal center T cells in the blood of humans. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Munusamy Ponnan S, Swaminathan S, Tiruvengadam K, et al. Induction of circulating T follicular helper cells and regulatory T cells correlating with HIV-1 gp120 variable loop antibodies by a subtype C prophylactic vaccine tested in a Phase I trial in India. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Choi JY, Ho JH, Pasoto SG, et al. Circulating follicular helper-like T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease activity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:988–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.He J, Tsai LM, Leong YA, et al. Circulating precursor CCR7(lo)PD-1(hi) CXCR5(+) CD4(+) T cells indicate Tfh cell activity and promote antibody responses upon antigen reexposure. Immunity. 2013;39:770–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Simpson N, Gatenby PA, Wilson A, et al. Expansion of circulating T cells resembling follicular helper T cells is a fixed phenotype that identifies a subset of severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:234–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu R, Wu Q, Su D, et al. A regulatory effect of IL-21 on T follicular helper-like cell and B cell in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang J, Shan Y, Jiang Z, et al. High frequencies of activated B cells and T follicular helper cells are correlated with disease activity in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;174:212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, et al. Human circulating PD-1+CXCR3-CXCR5+ memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity. 2013;39:758–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.MacLeod MK, David A, McKee AS, Crawford F, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Memory CD4 T cells that express CXCR5 provide accelerated help to B cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:2889–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, et al. Distinct memory CD4+ T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity. 2013;38:805–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Choi YS, Yang JA, Yusuf I, et al. Bcl6 expressing follicular helper CD4 T cells are fate committed early and have the capacity to form memory. J Immunol. 2013;190:4014–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Luthje K, Kallies A, Shimohakamada Y, et al. The development and fate of follicular helper T cells defined by an IL-21 reporter mouse. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Marshall HD, Chandele A, Jung YW, et al. Differential expression of Ly6C and T-bet distinguish effector and memory Th1 CD4(+) cell properties during viral infection. Immunity. 2011;35:633–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pepper M, Pagan AJ, Igyarto BZ, Taylor JJ, Jenkins MK. Opposing signals from the Bcl6 transcription factor and the interleukin-2 receptor generate T helper 1 central and effector memory cells. Immunity. 2011;35:583–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Crotty S Do Memory CD4 T Cells Keep Their Cell-Type Programming: Plasticity versus Fate Commitment? Complexities of Interpretation due to the Heterogeneity of Memory CD4 T Cells, Including T Follicular Helper Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pepper M, Jenkins MK. Origins of CD4(+) effector and central memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:467–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Asrir A, Aloulou M, Gador M, Perals C, Fazilleau N. Interconnected subsets of memory follicular helper T cells have different effector functions. Nat Commun. 2017;8:847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kim ST, Choi JY, Lainez B, et al. Human Extrafollicular CD4(+) Th Cells Help Memory B Cells Produce Igs. J Immunol. 2018;201:1359–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sidiropoulos K, Viteri G, Sevilla C, et al. Reactome enhanced pathway visualization. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rebhahn JA, Deng N, Sharma G, Livingstone AM, Huang S, Mosmann TR. An animated landscape representation of CD4+ T-cell differentiation, variability, and plasticity: insights into the behavior of populations versus cells. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2216–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]