Abstract

Glucuronoxylanases are endo-xylanases and members of the glycoside hydrolase family 30 subfamilies 7 (GH30-7) and 8 (GH30-8). Unlike for the well-studied GH30-8 enzymes, the structural and functional characteristics of GH30-7 enzymes remain poorly understood. Here, we report the catalytic properties and three-dimensional structure of GH30-7 xylanase B (Xyn30B) identified from the cellulolytic fungus Talaromyces cellulolyticus. Xyn30B efficiently degraded glucuronoxylan to acidic xylooligosaccharides (XOSs), including an α-1,2-linked 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronosyl substituent (MeGlcA). Rapid analysis with negative-mode electrospray-ionization multistage MS (ESI(−)-MSn) revealed that the structures of the acidic XOS products are the same as those of the hydrolysates (MeGlcA2Xyln, n > 2) obtained with typical glucuronoxylanases. Acidic XOS products were further degraded by Xyn30B, releasing first xylobiose and then xylotetraose and xylohexaose as transglycosylation products. This hydrolase reaction was unique to Xyn30B, and the substrate was cleaved at the xylobiose unit from its nonreducing end, indicating that Xyn30B is a bifunctional enzyme possessing both endo-glucuronoxylanase and exo-xylobiohydrolase activities. The crystal structure of Xyn30B was determined as the first structure of a GH30-7 xylanase at 2.25 Å resolution, revealing that Xyn30B is composed of a pseudo-(α/β)8-catalytic domain, lacking an α6 helix, and a small β-rich domain. This structure and site-directed mutagenesis clarified that Arg46, conserved in GH30-7 glucuronoxylanases, is a critical residue for MeGlcA appendage–dependent xylan degradation. The structural comparison between Xyn30B and the GH30-8 enzymes suggests that Asn93 in the β2–α2 loop is involved in xylobiohydrolase activity. In summary, our findings indicate that Xyn30B is a bifunctional endo- and exo-xylanase.

Keywords: glycoside hydrolase, X-ray crystallography, enzyme structure, polysaccharide, mass spectrometry (MS), glucuronoxylanase, glycoside hydrolase family 30, Talaromyces cellulolyticus, xylobiohydrolase, xylooligosaccharide

Introduction

Xylan is a major component of plant cell walls and hardwood hemicellulose. It is a heteropolysaccharide consisting of β-1,4-d-xylopyranose polymer as the main chain and some side-chain residues, such as α-l-arabinofuranose and 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronic acid (MeGlcA).2 Bacteria and fungi produce several kinds of endo-β-1,4-xylanases (EC 3.2.1.8) to cleave xylan backbones (1). These enzymes belong to a variety of glycoside hydrolase (GH) families (families 5, 8, 10, 11, 30, 43, 51, 98, and 141) in the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZy) database (1). Glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolases (glucuronoxylanases: EC 3.2.1.136) are classified in the GH30 family (previously in the GH5 family) and degrade the glucuronoxylan main chain at the second glycosidic linkage from the MeGlcA residue toward the reducing end (2, 3). They exert no or very low effects on xylan or xylooligosaccharides (XOSs) when the MeGlcA side chain is absent (2–6). The bacterial and fungal enzymes are further classified in the GH30 subfamilies 8 (GH30-8) and 7 (GH30-7), respectively, by phylogenetic analysis based on their amino acid sequences (7). The GH30 enzymes of Actinobacteria are categorized into both GH30–8 and GH30–7.

Many studies on bacterial GH30-8 glucuronoxylanases have been performed (2–6, 8). Mutational analyses of EcXynA from Dickeya chrysanthemi (formerly Erwinia chrysanthemi) and BsXynC from Bacillus subtilis and their structural analyses when complexed with aldouronic acids have revealed that the ionic interaction between a conserved Arg residue (Arg293 of EcXynA and Arg272 of BsXynC) and a carboxyl group on the MeGlcA side chain confers specificity for glucuronoxylan (9–11). Several GH30-8 xylanases, including those without the conserved Arg residue, have been reported to degrade both glucuronoxylan and arabinoxylan without exhibiting the MeGlcA appendage dependence (12, 13).

In contrast to bacterial enzymes, there are very few reports on fungal GH30-7 xylanases. Cellulolytic fungi, such as Trichoderma reesei, Myceliophthora thermophila, and Talaromyces cellulolyticus, which are promising enzyme sources for hydrolyzing lignocellulosic biomass (14–16), encode multiple putative GH30-7 xylanases in their genomes. The GH30-7 xylanases are secreted in cellulosic and xylanosic culture conditions (17, 18). However, information on their catalytic properties is limited, except for those expressed in T. reesei. This fungus produces two types of GH30-7 xylanases possessing exo-xylanase activity toward the reducing end of xylan (XYN IV) and glucuronoxylanase activity similar to the bacterial GH30-8 enzyme (XYN VI) (19, 20). The notable difference in the sequences of fungal GH30-7 and GH30-8 xylanases is the absence of an Arg293 counterpart (20). Without a three-dimensional structure of GH30-7, it is hard to determine the structural underpinnings of the MeGlcA appendage dependence of XYN VI and structural differences between exo-xylanase and glucuronoxylanase.

In a preliminary study, we detected two GH30-7 proteins from T. cellulolyticus, termed Xyn30A (NCBI protein ID GAM43270) and Xyn30B (GAM36763), which were secreted as major proteins in a culture containing birchwood glucuronoxylan (Fig. S1). Xyn30A has been predicted to be a putative exo-xylanase from its relatively high sequence similarity with XYN IV (77%), whereas Xyn30B has remained to be identified due to lack of an appropriate GH30-homologous protein. Here, we report the catalytic properties and crystal structure of Xyn30B. Xyn30B exhibited an obvious, MeGlcA appendage–dependent glucuronoxylanase activity. Moreover, we found that Xyn30B exhibits a novel xylobiohydrolase activity wherein xylobiose (Xyl2) is released from the nonreducing end of β-1,4-xylan and XOS. This unique bifunctional activity and the conserved Arg residue found in Xyn30B are discussed based on the structural comparison between GH30-8 and GH30-7 xylanase.

Results

Amino acid sequence analysis of Xyn30B

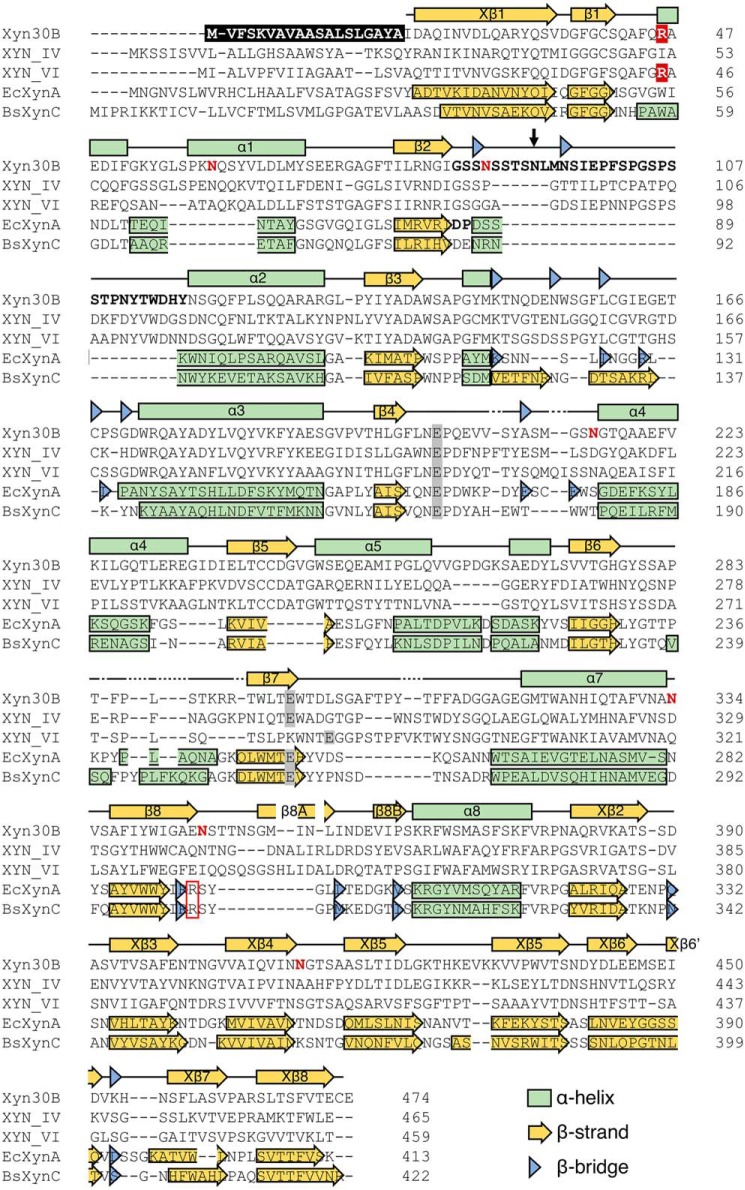

The Xyn30B gene is composed of 1,425 bp without introns in the T. cellulolyticus genome and encodes a protein consisting of 474 amino acid residues. Xyn30B has a relatively high amino acid sequence identity with fungal GH30-7 enzymes, such as XYN IV (38.2%) and XYN VI (42.2%) from T. reesei and XYLD (53.4%) from Bispora sp. (19–21), as compared with bacterial GH30-8 enzymes, such as EcXynA (24.4%), BsXynC (23.3%), and CaXyn30A from Clostridium acetobutylicum (26.3%) (2, 12, 22). Two conserved catalytic residues previously identified in GH30 xylanase—a general acid/base residue and a nucleophilic residue—were found to correspond with Glu202 and Glu297, respectively, in Xyn30B (Fig. 1, gray highlights). As with XYN IV and XYN VI, an Arg residue responsible for recognition of the MeGlcA in GH30-8 enzymes is not conserved in Xyn30B (Fig. 1, red box). The Xyn30B amino acid sequence includes a signal sequence (residues 1–22) as predicted by the SignalP server (23). The cleavage site of the signal peptide was estimated to lie between Ala19 and Ile20 or between Ala22 and Gln23. Eight of the N-glycosylation sites (Asn60, Asn88, Asn111, Asn154, Asn215, Asn334, Asn346, and Asn412) were predicted by the NetNglyc server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/).3

Figure 1.

Multiple-sequence alignments of GH30 xylanases. Primary structures of Xyn30B, XYN IV, XYN VI, EcXynA, and BsXynC were used for sequence alignments. The features are shown as follows: conserved Arg residues in GH30-8 glucuronoxylanases (red box); catalytic Glu residues (highlighted in gray); predicted signal sequence of Xyn30B (highlighted in black); β2–α2 loop of Xyn30B and EcXynA (boldface type); N-glycosylated Asn residues (red characters); the conserved Arg residues in GH30-7 glucuronoxylanases (highlighted in red); Asn93 of Xyn30B (indicated by a black arrow). Secondary structures of Xyn30B are shown above the sequences. Each of the secondary structures of EcXynA and BsXynC is also indicated within the sequence. N-terminal signal sequence, N-glycosylation sites, and secondary structures are based on assignment by the crystal structure.

Xyn30B was overexpressed using the T. cellulolyticus homologous expression system (24). SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified enzyme showed a molecular mass slightly larger than 49,403 Da, which has been estimated from the primary structure excluding the N-terminal signal peptide (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the average molecular mass of Xyn30B determined by TOF-MS was 56,354 Da, indicating that Xyn30B was glycosylated at several sites. The glycosylation sites in Xyn30B were assigned by X-ray crystallography, as described below.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified Xyn30B. Lane 2, purified Xyn30B; lane 1, standards. Molecular masses of the standards are indicated on the left. Arrow, Xyn30B position.

Enzyme characterization

Xyn30B exhibited xylanase activity on beechwood xylan (11.3 units mg−1) and birchwood xylan (9.0 units mg−1), whereas degradation activities for arabinoxylan, carboxymethyl cellulose, glucomannan, and xyloglucan were not detected by the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method. The optimum pH and temperature for hydrolysis of beechwood xylan were estimated around pH 4 and 50 °C, respectively (Fig. S2). Xyn30B retained more than 90% activity after incubation for 30 min at 40 °C in pH over a range of 3–6.5 and was stable for 24 h at temperatures below 40 °C at pH 4.0.

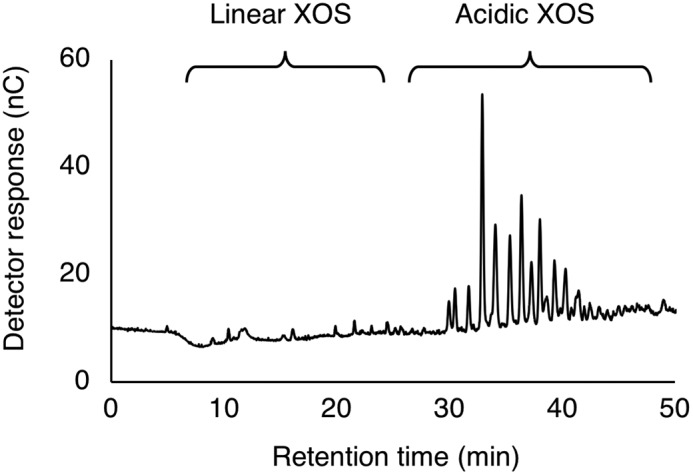

The initial degradation product of beechwood xylan by Xyn30B was found to be acidic XOSs, whereas linear oligosaccharides and xylose were hardly detected (Fig. 3). These observations indicate that Xyn30B is a glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase. Xyn30B also degraded the MeGlcA-appended oligosaccharide analogue, borohydride-reduced aldotetrauronic acid (BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3), into aldotriuronic acid (MeGlcA2Xyl2) and xylitol. Kinetic parameters were also determined as follows: Km = 19 mg ml−1 and kcat = 17 s−1 for beechwood xylan; Km = 0.064 mm and kcat = 23 s−1 for BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3. The low Km value for BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3 suggests that Xyn30B has high affinity for MeGlcA.

Figure 3.

HPAEC-PAD chromatogram of initial degradation product of beechwood xylan by Xyn30B. The reaction mixture containing 10 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan, 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.0, and 10 μg ml−1 Xyn30B was incubated at 40 °C for 1 h followed by incubation at 99 °C for 5 min to stop enzyme reaction.

Molecular and structural characterization of the acidic XOS products

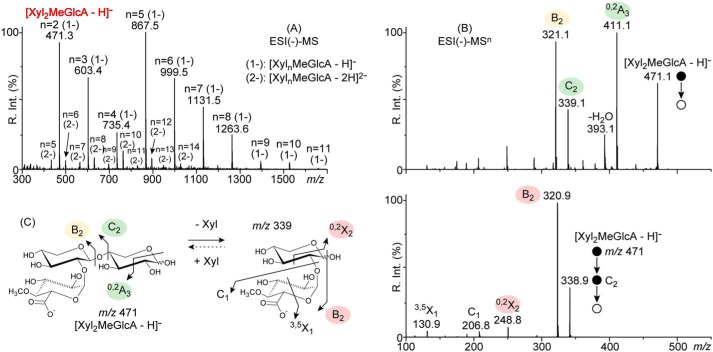

The molecular content in acidic XOS produced by Xyn30B was evaluated by ESI(−)-MS (Fig. 4A). Acidic products were readily observed as singly and doubly charged deprotonated species generically labeled [XylnMeGlcA − H]− (1−, mainly COO− from MeGlcA) and [XylnMeGlcA − 2H]2− (2−, COO− from MeGlcA and O− from anomeric carbon). They correspond to the XOS backbones formed by n xylose units and carrying one MeGlcA moiety with no information about its position. The ESI(−) analysis filters the oligoxylose species, Xyln, carrying no acidic moiety and allows for instant visualization of the shortest acidic product, which was found to be Xyl2MeGlcA at m/z 471 (Fig. 4A, highlighted in boldface red) and associated with a broad distribution of longer congeners up to Xyl14MeGlcA at m/z 1,027 (2−).

Figure 4.

ESI(−)-MSn analysis of the acidic XOS products of Xyn30B. A, ESI(−)-MS spectrum of the acidic products of Xyn30B. B, ESI(−)-MS2 and MS3 spectra of the shortest deprotonated acidic product [Xyl2MeGlcA − H]− at m/z 471 and C2 at m/z 339 formed upon glycosidic bond cleavage. C, fragmentation pathways.

The position of the MeGlcA moiety along the XOS chain (reducing end, nonreducing end, or in between) was further revealed using a multistage MS procedure (MSn). Upon activation in MS2 (Fig. 4B), the [Xyl2MeGlcA − H]− expelled a neutral C2H4O2 via a cross-ring cleavage, yielding 0,2A3 at m/z 411 (−60 Da) concomitantly to a xylose unit via a glycosidic bond cleavage that yielded a C2 at m/z 339 (−132 Da). As the precursor ion is two xylose units long, it instantly indicates that the MeGlcA is located at the nonreducing end of Xyl2 (Fig. 4C). Both cross-ring and glycosidic bond cleavages have been found to occur only at the reducing ends of deprotonated acidic products (25, 26). The ESI(−)-MS3 spectrum of C2 displays two product ions formed upon its dehydration (B2 at m/z 321, −18 Da) and a cross-ring cleavage of the last xylose moiety (0,2X2 at m/z 249) as the two sole fragmentation pathways that are opened up by the MeGlcA position at the reducing end of the activated species (Fig. 4B).

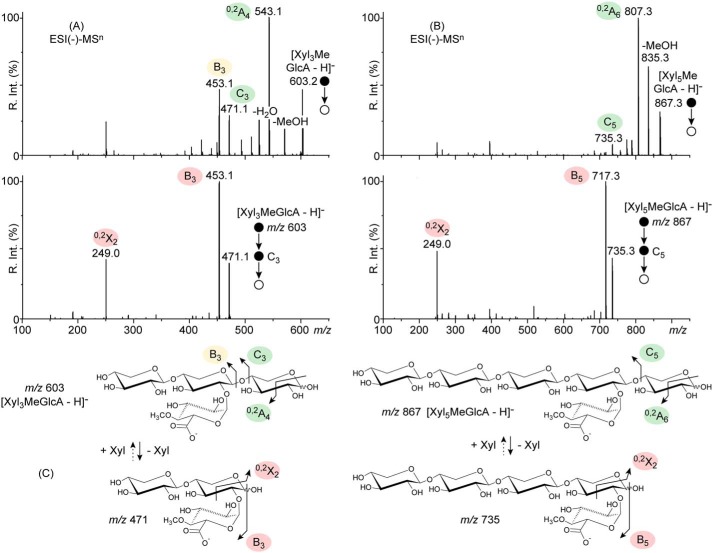

Both the cross-ring cleavage (yielding 0,2A4 at m/z 543) and the glycosidic bond cleavage (yielding C3 at m/z 471) were observed in the ESI(−)-MS2 fingerprint of the deprotonated acidic product, [Xyl3MeGlcA − H]−, at m/z 603 (Fig. 5A), indicating that the MeGlcA residue is not located at its reducing end. In the MS3 spectra (Fig. 5A), C3 was found to dissociate into B3 at m/z 453 (dehydration, −18 Da) and 0,2X2 only (cross-ring cleavage at the reducing end). Deviating from the MS2 spectrum of [Xyl2MeGlcA − H]− (Fig. 4B) but resembling the MS3 pattern of C2 from [Xyl2MeGlcA − H]−, it unambiguously localized the acidic MeGlcA pendant group at the reducing end of C3. In a reverse chain reconstruction, one xylose unit was added to the reducing end of C3, demonstrating that [Xyl3MeGlcA − H]− carries the glucuronic acid moiety one unit away from the reducing end (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

ESI(−)-MSn analysis of the longer acidic XOS products than Xyl2MeGlcA of Xyn30B. A, ESI(−)-MS2 and MS3 spectra of the deprotonated acidic product [Xyl3MeGlcA − H]− at m/z 603 and C3 at m/z 471 formed upon glycosidic bond cleavage. B, ESI(−)-MS2 and MS3 spectra of the deprotonated acidic product [Xyl5MeGlcA − H]− at m/z 867 and C5 at m/z 735 formed upon glycosidic bond cleavage. C, fragmentation pathways. Minor C1 and 3,5X1 product ions are unseen due to the cut-off of the ion trap (lower bound of the measurable mass range, dictated by the mass of the precursor ion).

A similar conclusion was drawn for [Xyl5MeGlcA − H]− at m/z 867 (Fig. 5B); the ESI(−)-MS2 spectrum barely displayed a xylose-shorter C5 ion product at m/z 735 (glycosidic bond cleavage at the reducing end), indicating the MeGlcA is not located at the reducing end but probably one unit away, considering the low intensity of C5 (26). Its ESI(−)-MS3 fingerprint was eventually identical to the previous MS3 pattern of C3 from [Xyl3MeGlcA − H]− (Fig. 5A) with the B5 and 0,2X2 product ions only (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the MeGlcA is positioned at the reducing end of C5, one unit away for [Xyl5MeGlcA − H]−. This indicates a generic MeGlcA2Xyln (n > 1) shape for the all of the acidic products released using Xyn30B (Fig. 4A). From these results, Xyn30B appears to specifically cleave glucuronoxylan at the second glycosidic linkage from the MeGlcA residue toward the reducing end, similarly to typical GH30 glucuronoxylanases.

Xylobiohydrolase activity

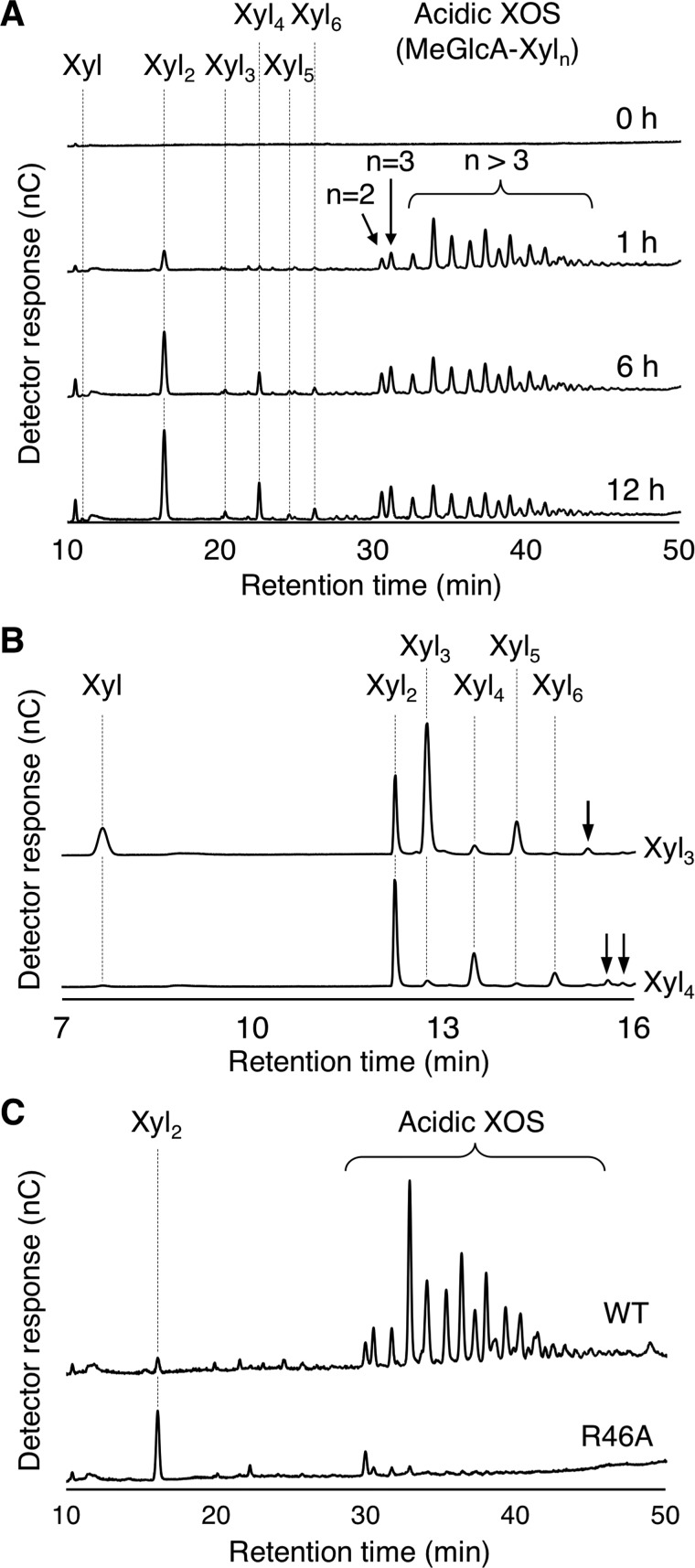

During the hydrolysis of beechwood xylan by Xyn30B, we noticed that Xyl2 was produced after prolonged incubation and increased protein loading of the reaction mixture (Fig. 6A). The increases in MeGlcA2Xyl2 and MeGlcA2Xyl3 were also observed with a decrease in longer acidic XOS in the mixture. These results indicate that Xyl2 was produced by further degradation of the acidic XOS. The specific production of Xyl2 suggests that Xyn30B has xylobiohydrolase activity, releasing Xyl2 units from the acidic XOSs that were generated in the initial stage of the reaction. This activity was predicted to release the product from the nonreducing end of MeGlcA2Xyln. In addition, the production of xylotetraose (Xyl4) and xylohexaose (Xyl6) was significantly increased with increasing time compared with that of xylotriose (Xyl3) and xylopentaose (Xyl5) (Fig. 6A). The product concentrations are shown in Table S1. These observations imply that the xylobiohydrolase activity was accompanied by transglycosylation activity, which transfers the Xyl2 from the acidic XOS to the free acceptors (Xyl2 and Xyl4).

Figure 6.

HPAEC-PAD profiles of Xyn30B reaction products. A, time course analysis of Xyn30B products from beechwood xylan. Hydrolysis was performed at 40 °C in a mixture consisting of 10 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan and 100 μg ml−1 Xyn30B in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0). B, XOSs from Xyl3 (top) and Xyl4 (bottom) produced by Xyn30B. The hydrolysis of 10 mm Xyl3 and 10 mm Xyl4 was performed using 100 μg ml−1 Xyn30B in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0) at 40 °C for 60 min. Arrows indicate linear XOSs that are longer than Xyl6. C, comparison of the degradation profiles of beechwood xylan by Xyn30B and R46A. Hydrolysis was performed at 40 °C for 60 min in a mixture consisting of 10 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan and 20 μg ml−1 enzyme in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0).

The xylobiohydrolase activity of Xyn30B was also confirmed for linear XOS, which was MeGlcA appendage–independent. When Xyl3 was used as the substrate, xylose and Xyl2 were produced as hydrolysates, and Xyl5 was formed through a transglycosylation (Fig. 6B). The hydrolase and transglycosylation activities of Xyl3 were 0.388 and 0.303 units mg−1 for the production of xylose and Xyl5, respectively. The major products from Xyl4 were identified as Xyl2 and Xyl6. A small amount of unidentified XOS longer than Xyl6 was also observed during the hydrolysis of these substrates, probably due to further transglycosylation (Fig. 6B, arrows). In contrast, no products were produced when only Xyl2 was used as the substrate (data not shown), suggesting that transglycosylation occurs during the hydrolysis. These results indicate that Xyn30B is a bifunctional enzyme possessing both MeGlcA appendage–dependent glucuronoxylanase activity and xylobiohydrolase (including transglycosylation) activity.

X-ray crystallography of Xyn30B

The crystal structure of Xyn30B was determined at 2.25 Å resolution by molecular replacement using CaXyn30A as the search model (PDB code 5CXP). The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. The Xyn30B crystal was in the P212121 space group with two protein molecules (chains A and B) in the asymmetric unit. Amino acid residues numbered 20–473 were assigned to chains A and B with the electron density map indicating that the N-terminal signal sequence was cleaved between Ala19 and Ile20. Glu474, which is the C-terminal residue, could not be assigned due to disorder.

Table 1.

Statistics for X-ray crystallography

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 48.26–2.25 (2.28–2.25)a |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 83.2, 114.9, 118.5 |

| No. of reflections | 370,211 (16,467) |

| No. of unique reflections | 54,785 (2,649) |

| Redundancy | 6.8 (6.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.5) |

| I/〈σ(I)〉 | 15.1 (3.2) |

| Rmerge (%) | 10.5 (73.1) |

| CC½ | 0.998 (0.819) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 48.25–2.25 (2.31–2.25) |

| No. of reflections | 51,791 (3,757) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Rwork (%) | 16.6 (23.9) |

| Rfree (%) | 20.2 (28.5) |

| No. of molecules in an asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) /No. of atoms | |

| Proteins | 31.19/7,004 |

| Sugar chains | 49.76/426 |

| Water | 33.91/384 |

| Root mean square deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å)/bond angles (degrees) | 0.006/1.492 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 96.1 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.7 |

| Outlier (%) | 0.2 |

| PDB code | 6IUJ |

a Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

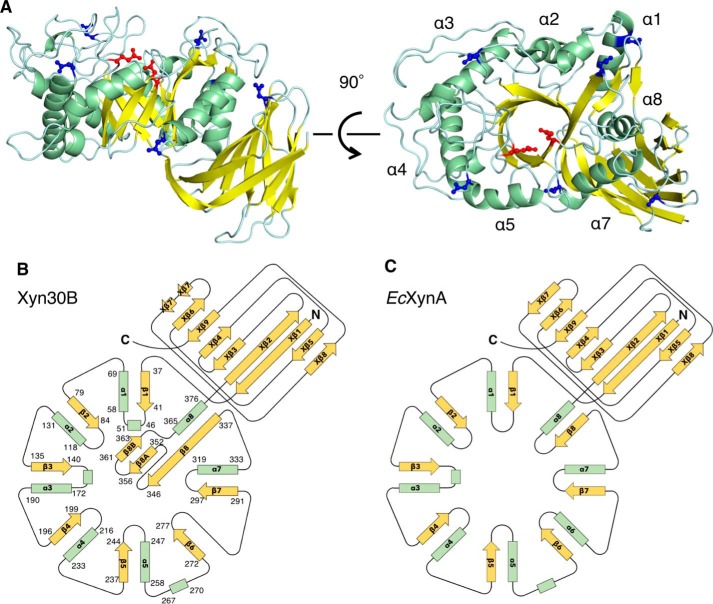

The overall structure of Xyn30B was similar to bacterial GH30-8 xylanases, such as EcXynA, which is composed of an (α/β)8-catalytic domain formed by eight α-helices (α1–α8), eight β-strands (β1–β8), and a small β-rich domain consisting of nine β-strands (Xβ1– Xβ9) (Fig. 7) (27). Xyn30B lacks a helix corresponding with α6 and possesses a β-sheet consisting of three β-strands (β8, β8A, and β8B) (Fig. 7, A and B). A loop structure is inserted in the middle of Xβ7, which separates the Xβ7-strands, Xβ7 and Xβ7′. The putative catalytic Glu residues (Glu202 and Glu297) are located in the catalytic cleft (Fig. 7A, red). In the electron density maps, sugar chains are observed at Asn60, Asn88, Asn215, Asn334, Asn346, and Asn412 (Fig. 7A (blue) and Figs. S3 and S4). Asn111 and Asn154 are not glycosylated, although they were predicted to be glycosylation sites by the NetNglyc server. Cys242 and Cys243 form an intramolecular disulfide bond.

Figure 7.

Overall structure of Xyn30B. A, the crystal structure of Xyn30B is shown as a ribbon model. Helix, strand, and loop structures are colored in green, yellow, and cyan, respectively. Catalytic Glu residues (Glu202 and Glu297) are shown as red sticks. N-Glycosylated asparagine residues (Asn60, Asn88, Asn215, Asn334, Asn346, and Asn412) are shown as blue sticks. Positions of the α-helices of the (α/β)8-barrel are indicated as α1–α8. B and C, topology diagrams of Xyn30B (B) and EcXynA (C) (PDB code 2Y24) (9).

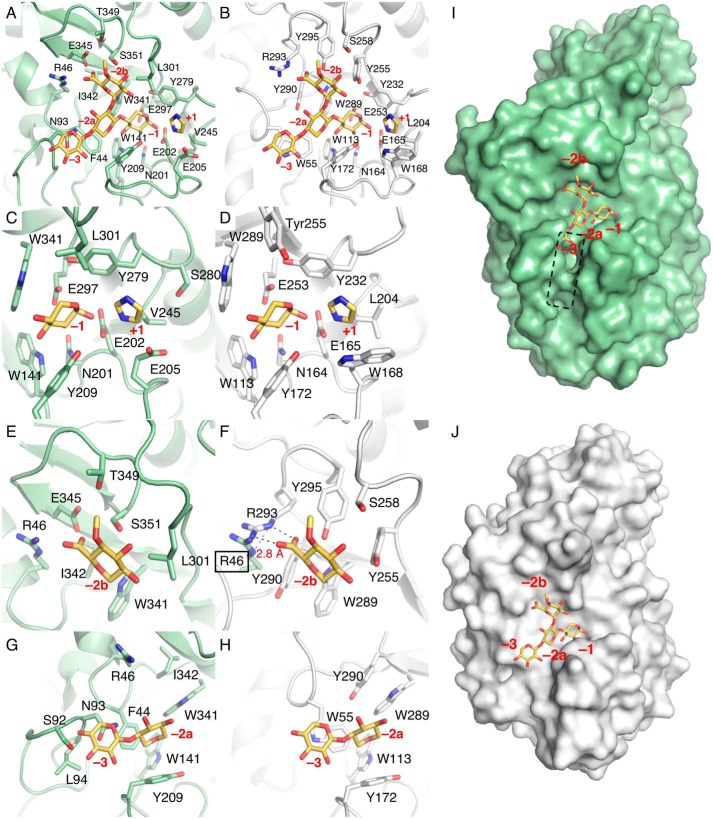

To clarify the Xyn30B substrate recognition mechanism, the crystal structure was superimposed on the EcXynA model complexed with MeGlcA2Xyl3 and imidazole (PDB code 2Y24) (Fig. 8A). In the EcXynA–ligand complex, three xylose residues of MeGlcA2Xyl3 are located in the subsite −1, −2a, and −3; a MeGlcA residue is in the subsite −2b; and an imidazole is in the putative +1 subsite (Fig. 8B) (9). Amino acid residues in the +1 and −1 subsites of the two enzymes are highly conserved except for a few variations (Fig. 8, C and D). The residues corresponding to Trp141, Asn201, Glu202, Tyr209, Tyr279, Glu297, and Trp341 of Xyn30B are found in the subsites of EcXynA. Trp168 and Leu204 of EcXynA, which probably interact with substrates at the +1 subsite, are substituted by Glu205 and Val245 in Xyn30B, respectively (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

The active-site structure of Xyn30B. The Xyn30B model is superimposed on EcXynA complexed with MeGlcA2Xyl3 and imidazole (PDB code 2Y24). Atoms are colored as follows: carbon of Xyn30B (green); carbon of EcXyn30A (white); carbon of MeGlcA2Xyl3 and imidazole (yellow); oxygen (red); nitrogen (blue). Red letters, subsites. A, C, E, and G, Xyn30B and the superposed ligands in the EcXynA model. B, D, F, and H, EcXynA–ligands complex in the same orientation as in the left panels (Xyn30B; A, C, E, and G). A and B, components of the subsites +1, −1, −2a, −2b, and −3. C and D, amino acid residues at subsites +1 and −1. E, amino acid residues of subsite −2b and MeGlcA side chain. F, the structure of subsite −2b in EcXynA, including Arg46 of Xyn30B, superimposed with the EcXynA model. Black dashed lines indicate the interaction between Arg293 and MeGlcA side chain. A red dashed line indicates the distance between the ϵ nitrogen atoms of Arg46 of Xyn30B and Arg293 of Xyn30B. G and H, enlargement of subsites, −2a and −3. Asn93 of Xyn30B protrudes into subsite −3, which is the xylose-binding position of EcXynA. I and J, Van der Waals surface of Xyn30B (I) and EcXynA (J) with the MeGlcA2Xyl3 as sticks. The dashed line indicates the candidate locations of subsites −3 and −4 of Xyn30B.

The notable differences between Xyn30B and EcXynA are found at subsites −2b, −2a, and −3. Subsite −2b of Xyn30B is formed by Arg46, Leu301, Trp341, Ile342, Glu345, Thr349, and Ser351 (Fig. 8E). The residues are substantially different between Xyn30B and EcXynA except for Trp341, corresponding to EcXynA Trp289 (Fig. 8, E and F). Interestingly, the guanidinium group of Arg46 in Xyn30B is located in the same region as Arg293 in EcXynA (Fig. 8, E and F). EcXynA Arg293 is the important residue that forms an ionic interaction with the carboxyl group of the MeGlcA side chain (9–11). Therefore, Xyn30B Arg46 has been suggested to have the same role in position −2b as Arg293 found in bacterial GH30-8 enzymes.

Subsites at the −3 position of Xyn30B have limited space with the presence of the β2–α2 loop composed of Gly85–Tyr117 (Fig. 8, G and I) in contrast to that of EcXynA (Fig. 8, H and J). Binding of the nonreducing end of MeGlcA2Xyl3 seems to be blocked at the −3 position by the β2–α2 loop (Fig. 8I). This loop is significantly longer than the loop of EcXynA (Fig. 1 and Fig. S5). Asn93 on the tip of the loop is more specific in Xyn30B and has been predicted to be located proximal to the xylose at the −2a subsite (Fig. 8G). These observations suggest that the substrate binding at the −2a and −3 positions in Xyn30B is apparently different from that in EcXynA under the influence of the β2–α2 loop.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The role of Arg46 in Xyn30B was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis by substituting Arg46 for Ala (Xyn30B R46A). The specific activity of R46A for beechwood xylan was 3.52 units mg−1, which was ∼3.2-fold lower than that of the WT enzyme. The Km value of R46A for BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3 was not determined in this study, because the initial rate of xylitol production was not saturated, even at the substrate concentration of 24 mm. These results suggest that Arg46 within Xyn30B plays an important role in the recognition of MeGlcA side chain.

In contrast, the xylobiohydrolase and transglycosylation activities for Xyl3 were 0.505 units mg−1 and 0.371 units mg−1, respectively, which were both slightly higher than the WT enzyme. The degradation pattern of beechwood xylan by R46A exhibited significantly high production of xylobiose (Fig. 6C). Considering the hydrolytic activity of Xyn30B and R46A for Xyl3, acidic XOS appears to act as an inhibitor as well as a substrate during xylobiohydrolysis in the WT enzyme.

The endo-xylanase activity of R46A was suggested to be glucuronoxylan-specific, similar to the WT enzyme, based on the HPAEC elution pattern of acidic XOS in a reaction mixture wherein enzyme loading was increased (data not shown). The endo-xylanase activity for arabinoxylan was also not detected for R46A. These observations agree with previous reports suggesting that mutants of the conserved Arg residue in the bacterial GH30-8 enzymes, EcXynA and StXyn30A, which is the GH30 glucuronoxylanase from Streptomyces turgidiscabies, degrade glucuronoxylan in the same manner as the WT enzymes, whereas their catalytic efficiencies were lower (8, 11).

Discussion

This paper described the characterization and structural determination of the novel GH30-7 xylanase, Xyn30B, from T. cellulolyticus. Xyn30B displayed glucuronoxylan-specific endo-xylanase activity that has been reported in bacterial GH30-8 glucuronoxylanases and T. reesei GH30-7 XYN VI. X-ray crystallography of Xyn30B and site-directed mutagenesis revealed that Arg46 is important for recognition of the MeGlcA residue, corresponding to a conserved Arg293 of GH30-8 EcXynA. Xyn30B was demonstrated to release Xyl2 units from the nonreducing end of the acidic XOS and linear XOS in an exo-fashion and also to transfer Xyl2 to an aglycon receptor (Fig. 6, A and B). To our knowledge, this is the first evidence describing exo-type xylobiohydrolase activity. Although xylobiosyltransferase activity has been reported for GH10 endo-xylanase (28–30), xylobiose-specific transglycosylation in Xyn30B is expected to be more profitable for producing xylobioside products. A study of the transglycosylation reaction of Xyn30B is in progress. A dual function showing endo-/exo-xylanase activity has not been reported for bacterial GH30-8 glucuronoxylanase, whereas XYN VI is capable of slower but significant cleavage of unsubstituted parts of xylan and acidic XOS (20). The catalytic diversity observed in Xyn30B and XYN VI may be a common property of fungal GH30-7 glucuronoxylanases.

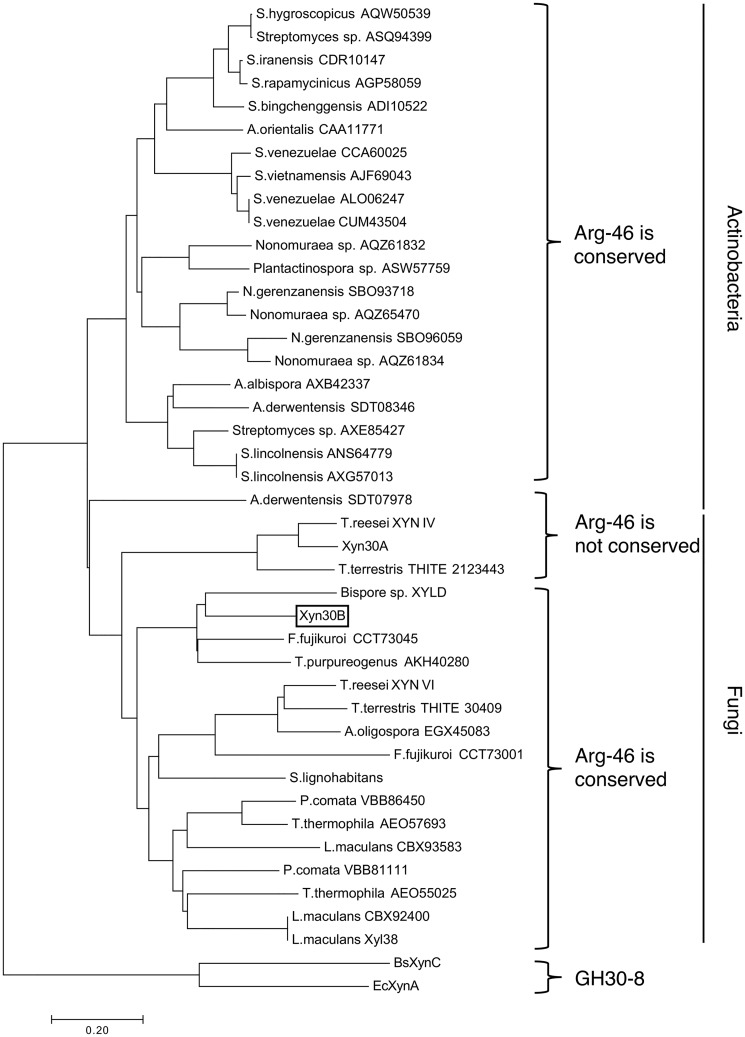

To confirm the generality of Arg46 in GH30-7 xylanases, the amino acid sequences of GH30-7 enzymes assigned in the CAZy database were aligned with Xyn30A and Xyn30B from T. cellulolyticus using molecular phylogenetic analysis. As of December 2018, 20 fungal enzymes and 22 actinobacterial enzymes are assigned to the GH30-7 subfamily in the CAZy database. Three enzymes were excluded for the analysis due to their lack of catalytic Glu residues. The sequence alignment revealed that GH30-7 and GH30-8 enzymes are obviously distributed into different clusters in the molecular phylogenetic tree and that GH30-7 enzymes are further divided into fungal and actinobacterial groups (Fig. 9). We found that Arg46 in Xyn30B is a highly conserved residue in the greater part of fungal and actinobacterial GH30-7 enzymes (Fig. S6). Fungal enzymes, which have a residue corresponding to Arg46 of Xyn30B, form a large cluster that includes Xyn30B and XYN VI (Fig. 9; Arg46 is conserved), suggesting that these enzymes share relatively high amino acid sequence similarity and therefore are glucuronoxylanases. This group included only one exception, Fusarium fujikuroi CCT73001, which has a His residue instead of an Arg residue. However, the His residue may form an ionic interaction with the MeGlcA residue of glucuronoxylan in the same manner as the Arg residue, because the side chain of His is positively charged in acidic conditions, which is a common condition of fungal xylanase. In contrast, XYN IV, Xyn30A, Thielavia terrestris THITE_2123443, and Actinoplanes derwentensis SDT08346, which do not possess a residue corresponding to Arg46 of Xyn30B, were located in an independent cluster (Fig. 9; Arg46 is not conserved). It seems reasonable that XYN IV does not have the Arg residue, because XYN IV is known to be an exo-xylanase but not a glucuronoxylanase (19). Xyn30A, T. terrestris THITE_2123443, and A. derwentensis SDT08346 are predicted to have enzyme activities that differ from glucuronoxylanase.

Figure 9.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of GH30 enzymes. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the amino acid sequences of GH30-7 enzymes and BsXynC and EcXynA by the neighbor-joining method (57). The 43 sequences used for the analysis are described in detail in Fig. S6. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 8.49592807 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units, indicative of the evolutionary distances. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (58) and are expressed as the number of amino acid substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 300 positions in the final data set. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (59).

Unique structural features in the crystal structure of Xyn30B, including a β2–α2 long loop, a β-sheet structure composed of β8-, β8A-, and β8B-strands (Fig. 7), and an intramolecular disulfide bond formed by Cys242 and Cys243, were found to be common features in fungal GH30-7 xylanases used for phylogenetic analysis, whereas they were not conserved in GH30-8 enzymes, such as EcXynA from Gram-negative D. chrysanthemi (PDB code 2Y24) (9) and BsXynC from Gram-positive B. subtilis (PDB code 3KL0) (10) (Figs. 1 and 7 (B and C)). It should be noted that the β2–α2 loop and the β-sheet structure contribute to the formation of subsites −2a and −2b, respectively, which are involved in the substrate recognition (Fig. 8, E and G). Alteration of −2a and −2b in GH30-7 provides a clue to understanding the catalytic diversity of Xyn30B.

Xyn30B sufficiently acts on linear XOS, whereas the specific activity of EcXynA for linear XOS is 3 orders of magnitude lower than that for aldouronic acid (9). The dual activity observed in Xyn30B is perhaps due to the contribution of the β2–α2 loop, which recognizes the nonreducing end of XOS, especially the Asn93 residue (Fig. 8, G and H). The subsite −3 of Xyn30B seems to be located at a different position from that of EcXynA with the presence of the loop; a candidate cleft has limited space, as shown by the dashed box in Fig. 8I. Our results indicate that the acidic XOS products and Xyl4 are degraded in a xylobiohydrolase manner, despite them being of adequate lengths to bind to the −3 subsite (Fig. 6, A and B). These facts suggest that introduction of the xylose residue into the −3 subsite is likely interrupted by the limited space of subsite −3.

In contrast, Xyn30B shows obvious endo-glucuronoxylanase activity for substrates with the MeGlcA side chain recognized at the −2b subsite (Fig. 8E). Such substrates must bind to the −3 subsite and further downstream. R46A was found to prefer the xylobiohydrolase activity rather than the glucuronoxylanase activity (Fig. 6C), indicating that disturbance of the interaction between the MeGlcA side chain and the −2b subsite decreased endo-glucuronoxylanase activity without influencing the xylobiohydrolase activity. Based on these considerations, we speculate that the interaction between the MeGlcA side chain and the −2b subsite plays an important role in orientating the xylan main chain to introduce the xylose residue into the −3 subsite. Further structural studies using enzyme–substrate complexes are necessary to understand the bifunctionality of Xyn30B.

Some studies have shown that the loop-like roof structure is important factor for determining whether exo- or endo-hydrolysis activity occurs. Proctor et al. (31) have converted the enzyme specificity of Cellvibrio japonicus GH43 exo-arabinanase (CjArb43A) to an endo-type enzyme by removing a steric interaction at the nonreducing end of substrates. Santos et al. (32) have clarified that the steric interaction between the long loop and an arabinose residue at the reducing end of arabinan is important for the exo-action of a GH43 arabinanase isolated from rumen metagenome. The roof structures and its interaction with substrate at reducing or nonreducing ends of substrates have been reported to be important for other GH enzymes, such as GH8, -26, -46, and -74 (33–36). These reports support our suggestion that the β2–α2 loop of Xyn30B is critical for its exo-xylobiohydrolase activity, because an additional region, including Asn93 (Ser90–Leu94) in the β2–α2 loop, appears to form a partial roof structure (Figs. 1 and 8I and Fig. S5). This region is specific in Xyn30B and is not seen in XYN VI. These differences could explain why significant exo-xylanase activity is detected in Xyn30B.

Experimental procedures

Strains and culture conditions

T. cellulolyticus CF-2612 (FERM BP-10848) were maintained on potato dextrose agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) plates (37). T. cellulolyticus YP-4 uracil autotroph was maintained on potato dextrose agar plates containing uracil and uridine at final concentrations of 1 g/liter each (24). The prototrophic transformants of T. cellulolyticus YP-4 expressing recombinant proteins Xyn30B and Xyn30B R46A were maintained on MM agar (1% (w/v) glucose, 10 mm NH4Cl, 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 6.5), 7 mm KCl, 2 mm MgSO4, and 1.5% (w/v) agar) plates (38). Recombinant enzymes were produced using a soluble starch medium containing 2% (w/v) soluble starch (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) and 0.2% (w/v) urea as described previously (24).

Plasmid construction and fungal transformation

The plasmid pANC202 (24), which contains the pyrF gene and the glucoamylase (glaA) promoter and terminator regions, was used to construct the plasmids pANC215 and pANC281, which were used to express recombinant Xyn30B and Xyn30B R46A, respectively. Escherichia coli DH5α (Takara Bio, Kyoto, Japan) were used for the DNA procedures. The primers for the genomic region encoding xyn30B were designed based on the genome sequence of T. cellulolyticus registered in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBankTM (DF933814.1) (39). The xyn30B gene was amplified using the forward primer 5′-ATTGTTAACAGAATGGTGTTCAGCAAAGTCGCCG (with the HpaI site underlined), and the reverse primer 5′-AATCCTGCAGGTCACTCGCACTCTGTAACAAAGCTTG (with the SbfI site underlined). The expression plasmid, pANC215, was constructed by ligating the xyn30B fragment that had been digested with HpaI/SbfI into the EcoRV/SbfI site of pANC202. The expression plasmid, pANC281, was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis of pANC215 using the KOD-plus- Mutagenesis kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The forward primer 5′-GCAGCGGAGGATATCTTCGGCAAGTACGGC (mutation site underlined) and the reverse primer 5′-TTGGAATGCCTGTGAGCAGCCAAAG were used for PCR. The presence of all ligated gene fragments and locations was verified by DNA sequencing.

The plasmids pANC215 and pANC281 were transformed into protoplasts of T. cellulolyticus YP-4 by nonhomologous integration into the host chromosomal DNA (38). The strains producing recombinant Xyn30B and Xyn30B R46A were selected based on the amount of recombinant protein in culture supernatant as visualized by SDS-PAGE using NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and were designated as Y215 and Y281, respectively.

Purification of Xyn30B and Xyn30B R46A

Purification of Xyn30B and Xyn30B R46A from culture supernatants of Y215 and Y281 strains, respectively, was performed using an ÄKTA purifier chromatography system (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) at room temperature. Culture supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-μm polyethersulfone membrane and desalted using a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) that had been equilibrated with 20 mm MES (pH 6.5). The desalted sample was applied to a Resource Q anion-exchange column (6 ml; GE Healthcare) that had been equilibrated with the same buffer, and protein peaks were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–0.5 m NaCl (20 column volumes) at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1. Fractions containing the target proteins were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and pooled. (NH4)2SO4 was added to a final concentration of 1.3 m, and then the samples were subjected to Source 15ISO (10 ml; GE Healthcare) hydrophobic interaction chromatography using a 1.3–0.7 m (NH4)2SO4 gradient (30 column volumes) in 20 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) at a flow rate of 2.5 ml min−1. The fractions containing target protein were pooled and were desalted and concentrated by ultrafiltration using Vivaspin 20-5K (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The purified enzymes were preserved in a 20 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) containing 0.01% NaN3 at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) using BSA (Thermo Scientific) as the protein standard.

Enzyme characterization

Xylanase activity was measured in a reaction mixture containing purified Xyn30B and 10 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland) in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0) at 40 °C for 15 min. The reducing sugars from depolymerization of the substrate were measured using the DNS method (40). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 μmol of reducing sugar/min.

The optimal pH values and pH stabilities were examined using McIlvaine buffer for pH adjustment (41). To determine the optimal pH values, the reaction mixtures from pH 2.0 to 6.5 were incubated at 40 °C for 15 min. To examine the pH stabilities, the enzymes were preincubated in buffer at pH values ranging from 2.0 to 7.0 for 30 min at 40 °C, and the residual activity was subsequently measured under standard assay conditions using 10 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan. The optimal reaction temperature was examined at 35–60 °C for 15 min in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0). To evaluate thermal stability, enzyme was preincubated in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0) at 4–60 °C for 30 min or 24 h, and then the residual activity was measured under standard assay conditions. To investigate the substrate specificity of Xyn30B, reaction mixture containing 10 mg ml−1 substrate was incubated at 40 °C in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0). The following substrates were used: birchwood xylan, beechwood xylan, wheat arabinoxylan (Megazyme), carboxymethyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich), konjac glucomannan (Megazyme), and xyloglucan (Megazyme).

Kinetic parameters were evaluated using 3.6–48 mg ml−1 beechwood xylan and 0.03–24 mm borohydride-reduced aldotetrauronic acid (23-(4-O-methyl-d-glucuronyl)-α-d-xylotriitol (BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3; Megazyme). The reaction was performed at 40 °C in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0). Enzyme activity for beechwood xylan was measured by the DNS method. Enzyme activity for BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3 was estimated by measuring the amount of released xylitol by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) analysis as described below (42). Kinetic constants were determined using the nonlinear least-squares data fitting method in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) (43).

Xylobiohydrolase and transglycosylation activities were measured in a reaction mixture containing purified Xyn30B and 4 mm xylotriose (Xyl3, Megazyme) in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0) at 40 °C for 15 min. The released products were determined by HPAEC-PAD analysis. One unit of xylobiohydrolase and transglycosylation activities was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the release of 1 μmol of xylose and Xyl5 per minute, respectively.

HPAEC-PAD analysis of hydrolysis reaction mixtures

HPAEC-PAD analysis of linear and acidic XOS hydrolysate was performed using a Dionex ICS-3000 ion chromatography system equipped with a CarboPac PA1 (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA).

Analysis of acidic XOS was conducted at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 as follows: (i) the system was equilibrated with 10 mm sodium hydroxide; (ii) after sample injection, 10 mm sodium hydroxide was run through the column for 3 min; (iii) a linear gradient of sodium hydroxide (10–100 mm) was run for 7 min; (iv) a linear gradient of sodium acetate (0–200 mm) in 100 mm sodium hydroxide was run for 40 min. The column was washed with 100 mm sodium hydroxide for 10 min after each sample analysis.

Analysis of xylose, xylitol, and linear XOS was conducted at 1 ml min−1 as follows: (i) the system was equilibrated with 10 mm sodium hydroxide; (ii) after sample injection, 10 mm sodium hydroxide was run through the column for 3 min; (iii) a linear gradient of sodium hydroxide (10–100 mm) was run for 2 min; and (iv) a linear gradient of sodium acetate (0–100 mm) in 100 mm sodium hydroxide was run for 8 min. The column was washed with 200 mm sodium acetate in 100 mm sodium hydroxide solution for 5 min after each sample analysis. Data were processed with Chromeleon software (Dionex). Xylose (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), Xyl2 (xylobiose, Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan), Xyl3, Xyl4 (Megazyme), Xyl5 (Megazyme), Xyl6 (Megazyme), and xylitol (Wako Pure Chemicals) were used as standards.

Mass spectrometry

The molecular mass of the purified Xyn30B was evaluated by MALDI-TOF MS with a Spiral TOF JMS-S3000 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The purified sample was applied to the MALDI target plate after dilution into a mixture containing 0.5% (w/v) sinapinic acid, 0.1% TFA, and 25% acetonitrile. Monovalent and bivalent ions from conalbumin (75 kDa) included in the Gel Filtration Calibration Kit HMW (GE Healthcare) were used for external mass calibration. Instrument control, data acquisition, and data processing of all experiments were achieved using MSTornado (JEOL).

Electrospray ionization single-stage and multistage MS in the negative ion mode (ESI(−)-MSn; n = 1–3) were used for the molecular and structural analyses of acidic XOS using an amaZon SL-STT2 ion trap (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Samples were diluted in methanol (MeOH) and introduced into the ionization source in infusion mode using a syringe pump at a flow rate of 10 μl min−1. The apparatus was operated in enhanced resolution mode (mass range: 50–2200 m/z, scanning rate: 8,100 m/z per second). In MSn experiments (n > 1), the width of the selection window was set at 1 Da to obtain clean isotopic selection. The amplification of the excitation was set according to the experiment to reach a survival yield (abundance of the precursor ion divided by the sum of the product and precursor ion abundances) at ∼20%. Instrument control, data acquisition, and data processing of all experiments were achieved using Compass 1.3 SR2 (Bruker), whereas mMass 5.5.0.0 (44) was used for data treatment and artworks.

X-ray crystallography

Purified Xyn30B was concentrated to 30 mg ml−1 for crystallization. Crystals were obtained with the hanging-drop vaper diffusion method at 20 °C for a week. The drop was composed of 1.5 μl of protein solution mixed with 1.5 μl of reservoir solution containing 30% PEG 4000, 0.1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 200 mm sodium acetate and equilibrated against 500 μl of reservoir solution.

The Xyn30B crystal was soaked with the reservoir solution supplemented with 30% glycerol as a cryoprotectant and then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data of the crystal were collected to 2.25 Å resolution at 100 K at the SPring-8 beamline BL44XU. Diffraction images were checked with adxv (http://www.scripps.edu/tainer/arvai/adxv.html)3 and integrated and scaled with XDS (version: January 26, 2018) (45). Phasing was performed using Molrep 11.6 in CCP4 7.0 (46, 47) with CaXyn30A (PDB code 5CXP) as the model, which had been processed using Sculptor in Phenix 1.12 (48, 49). The first model was refined using AutoBuild (50). The model was manually completed using Coot 0.8.9 and refined using Refmac 5.8 (51, 52). Model quality was verified using MolProbity 4.4 (53). Molecular figures were generated with Open-source PyMol 1.8 (54). Secondary structures of Xyn30B, EcXynA, and BsXynC were assigned using STRIDE (55).

Amino acid sequence alignment

Amino acid sequences of T. cellulolyticus Xyn30B (NCBI protein ID: GAM36763), T. reesei XYN IV (AAP64786), T. reesei XYN VI (EGR45006), D. chrysanthemi EcXynA (AAB53151), and B. subtilis BsXynC (CAA97612) were aligned by using the Clustal Omega server (56).

Author contributions

H. I. designed the study. H. I. and Y. N. prepared and characterized the enzymes. T. F. and S. I. collected the mass spectrometry data. Y. N. and M. W. conducted the X-ray crystallography experiments. A. M. and H. I. coordinated the study. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript and approved the final version.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Maya Ishii and Benchaporn Inoue for technical assistance. This work was performed at the BL44XU synchrotron beamline at SPring-8 under the Collaborative Research Program within the Institute for Protein Research at Osaka University (Harima, Japan; Proposals 2017B6767 and 2018A6863). We thank the beamline staff—Drs. Eiki Yamashita, Akifumi Higashiura, and Kenji Takagi—for assistance with data collection.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Table S1 and Figs. S1–S6.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 6IUJ) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- MeGlcA

- α-1,2-linked 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronosyl

- GH30-7 and GH30-8

- subfamily 7 and 8, respectively, of glycoside hydrolase family 30

- Xyn30B

- GH30-7 xylanase B from T. cellulolyticus

- XOS

- xylooligosaccharide

- EcXynA

- XynA from Dickeya chrysanthemi

- BsXynC

- XynC from Bacillus subtilis

- CaXyn30A

- Xyn30A from Clostridium acetobutylicum

- BR-MeGlcA3Xyl3

- borohydride-reduced aldotetrauronic acid

- MeGlcA2Xyl2

- aldotriuronic acid

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- MSn

- multistage mass spectrometry

- Xyl2

- xylobiose

- Xyl3

- xylotriose

- Xyl4

- xylotetraose

- Xyl5

- xylopentaose

- Xyl6

- xylohexaose

- HPAEC

- high-performance anion-exchange chromatography

- PAD

- pulsed amperometric detection

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- CAZy

- carbohydrate active enzymes

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- DNS

- 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

References

- 1. Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 10.1093/nar/gkt1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. St John F. J., Rice J. D., and Preston J. F. (2006) Characterization of XynC from Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis Strain 168 and analysis of its role in depolymerization of glucuronoxylan. J. Bacteriol. 188, 8617–8626 10.1128/JB.01283-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vršanská M., Kolenová K., Puchart V., and Biely P. (2007) Mode of action of glycoside hydrolase family 5 glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolase from Erwinia chrysanthemi. FEBS J. 274, 1666–1677 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valenzuela S. V., Diaz P., and Pastor F. I. (2012) Modular glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase with a family CBM35 carbohydrate-binding module. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 3923–3931 10.1128/AEM.07932-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Padilha I. Q. M., Valenzuela S. V., Grisi T. C. S. L., Díaz P., de Araújo D. A. M., and Pastor F. I. (2014) A glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase from a new Paenibacillus favisporus strain isolated from tropical soil of Brazil. Int. Microbiol. 17, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. St John F. J., Crooks C., Dietrich D., and Hurlbert J. (2016) Xylanase 30 A from Clostridium thermocellum functions as a glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 133, S445–S451 10.1016/j.molcatb.2017.03.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. St John F. J., González J. M., and Pozharski E. (2010) Consolidation of glycosyl hydrolase family 30: a dual domain 4/7 hydrolase family consisting of two structurally distinct groups. FEBS Lett. 584, 4435–4441 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maehara T., Yagi H., Sato T., Ohnishi-Kameyama M., Fujimoto Z., Kamino K., Kitamura Y., St John F. J., Yaoi K., and Kaneko S. (2018) GH30 glucuronoxylan-specific xylanase from Streptomyces turgidiscabies C56. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e01850–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Urbániková L., Vršanská M., Mørkeberg Krogh K. B. R., Hoff T., and Biely P. (2011) Structural basis for substrate recognition by Erwinia chrysanthemi GH30 glucuronoxylanase. FEBS J. 278, 2105–2116 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. St John F. J., Hurlbert J. C., Rice J. D., Preston J. F., and Pozharski E. (2011) Ligand bound structures of a glycosyl hydrolase family 30 glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolase. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 92–109 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Šuchová K., Kozmon S., Puchart V., Malovíková A., Hoff T., Mørkeberg Krogh K. B. R., and Biely P. (2018) Glucuronoxylan recognition by GH 30 xylanases: a study with enzyme and substrate variants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 643, 42–49 10.1016/j.abb.2018.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. St John F. J., Dietrich D., Crooks C., Balogun P., de Serrano V., Pozharski E., Smith J. K., Bales E., and Hurlbert J. C. (2018) A plasmid borne, functionally novel glycoside hydrolase family 30, subfamily 8 endoxylanase from solventogenic Clostridium. Biochem. J. 475, 1533–1551 10.1042/BCJ20180050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. St John F. J., Dietrich D., Crooks C., Pozharski E., González J. M., Bales E., Smith K., and Hurlbert J. C. (2014) A novel member of glycoside hydrolase family 30 subfamily 8 with altered substrate specificity. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2950–2958 10.1107/S1399004714019531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karnaouri A., Topakas E., Antonopoulou I., and Christakopoulos P. (2014) Genomic insights into the fungal lignocellulolytic system of Myceliophthora thermophila. Front. Microbiol. 5, 281 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fujii T., Inoue H., Yano S., and Sawayama S. (2018) Strain improvement for industrial production of lignocellulolytic enzyme by Talaromyces cellulolyticus. in Fungal Cellulolytic Enzymes (Fang X., and Qu Y., eds) pp. 58–68, Springer, Singapore [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peterson R., and Nevalainen H. (2012) Trichoderma reesei RUT-C30: thirty years of strain improvement. Microbiology 158, 58–68 10.1099/mic.0.054031-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adav S. S., Chao L. T., and Sze S. K. (2012) Quantitative secretomic analysis of Trichoderma reesei strains reveals enzymatic composition for lignocellulosic biomass degradation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111.012419 10.1074/mcp.M111.012419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kolbusz M. A., Di Falco M., Ishmael N., Marqueteau S., Moisan M. C., Baptista C. D. S., Powlowski J., and Tsang A. (2014) Transcriptome and exoproteome analysis of utilization of plant-derived biomass by Myceliophthora thermophila. Fungal Genet. Biol. 72, 10–20 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tenkanen M., Vršanská M., Siika-aho M., Wong D. W., Puchart V., Penttilä M., Saloheimo M., and Biely P. (2013) Xylanase XYN IV from Trichoderma reesei showing exo- and endo-xylanase activity. FEBS J. 280, 285–301 10.1111/febs.12069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Biely P., Puchart V., Stringer M. A., and Mørkeberg Krogh K. B. R. (2014) Trichoderma reesei XYN VI: a novel appendage-dependent eukaryotic glucuronoxylan hydrolase. FEBS J. 281, 3894–3903 10.1111/febs.12925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo H., Yang J., Li J., Shi P., Huang H., Bai Y., Fan Y., and Yao B. (2010) Molecular cloning and characterization of the novel acidic xylanase XYLD from Bispora sp. MEY-1 that is homologous to family 30 glycosyl hydrolases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86, 1829–1839 10.1007/s00253-009-2410-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hurlbert J. C., and Preston J. F. 3rd (2001) Functional characterization of a novel xylanase from a corn strain of Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2093–2100 10.1128/JB.183.6.2093-2100.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nielsen H. (2017) Predicting secretory proteins with signalP. Methods Mol. Biol. 1611, 59–73 10.1007/978-1-4939-7015-5_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Inoue H., Fujii T., Yoshimi M., Taylor L. E. 2nd, Decker S. R., Kishishita S., Nakabayashi M., and Ishikawa K. (2013) Construction of a starch-inducible homologous expression system to produce cellulolytic enzymes from Acremonium cellulolyticus. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40, 823–830 10.1007/s10295-013-1286-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reis A., Domingues M. R. M., Domingues P., Ferrer-Correia A. J., and Coimbra M. A. (2003) Positive and negative electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry as a tool for structural characterisation of acid released oligosaccharides from olive pulp glucuronoxylans. Carbohydr. Res. 338, 1497–1505 10.1016/S0008-6215(03)00196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fouquet T., Sato H., Nakamichi Y., Matsushika A., and Inoue H. (2018) Electrospray multistage mass spectrometry in the negative ion mode for the unambiguous molecular and structural characterization of acidic hydrolysates from 4-O-methylglucuronoxylan generated by endoxylanases. J. Mass Spectrom. 10.1002/jms.4321 10.1002/jms.4321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Larson S. B., Day J., Barba de la Rosa A. P., Keen N. T., and McPherson A. (2003) First crystallographic structure of a xylanase from glycoside hydrolase family 5: implications for catalysis. Biochemistry 42, 8411–8422 10.1021/bi034144c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhengqiang J., Kobayashi A., Ahsan M. M., Lite L., Kitaoka M., and Hayashi K. (2001) Characterization of a thermostable family 10 endo-xylanase (XynB) from Thermotoga maritima that cleaves p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xyloside. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 92, 423–428 10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80290-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang Z., Zhu Y., Li L., Yu X., Kusakabe I., Kitaoka M., and Hayashi K. (2004) Transglycosylation reaction of xylanase B from the hyperthermophilic Thermotoga maritima with the ability of synthesis of tertiary alkyl β-d-xylobiosides and xylosides. J. Biotechnol. 114, 125–134 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gatard S., Plantier-Royon R., Rémond C., Muzard M., Kowandy C., and Bouquillon S. (2017) Preparation of new β-d-xyloside- and β-d-xylobioside-based ionic liquids through chemical and/or enzymatic reactions. Carbohydr. Res. 451, 72–80 10.1016/j.carres.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Proctor M. R., Taylor E. J., Nurizzo D., Turkenburg J. P., Lloyd R. M., Vardakou M., Davies G. J., and Gilbert H. J. (2005) Tailored catalysts for plant cell-wall degradation: redesigning the exo/endo preference of Cellvibrio japonicus arabinanase 43A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 102, 2697–2702 10.1073/pnas.0500051102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santos C. R., Polo C. C., Costa M. C. M. F., Nascimento A. F. Z., Meza A. N., Cota J., Hoffmam Z. B., Honorato R. V., Oliveira P. S. L., Goldman G. H., Gilbert H. J., Prade R. A., Ruller R., Squina F. M., Wong D. W. S., and Murakami M. T. (2014) Mechanistic strategies for catalysis adopted by evolutionary distinct family 43 arabinanases. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 7362–7373 10.1074/jbc.M113.537167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cartmell A., Topakas E., Ducros V. M. A., Suits M. D. L., Davies G. J., and Gilbert H. J. (2008) The Cellvibrio japonicus mannanase CjMan26C displays a unique exo-mode of action that is conferred by subtle changes to the distal region of the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34403–34413 10.1074/jbc.M804053200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fushinobu S., Hidaka M., Honda Y., Wakagi T., Shoun H., and Kitaoka M. (2005) Structural basis for the specificity of the reducing end xylose-releasing exo-oligoxylanase from Bacillus halodurans C-125. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17180–17186 10.1074/jbc.M413693200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yao Y. Y., Shrestha K. L., Wu Y. J., Tasi H. J., Chen C. C., Yang J. M., Ando A., Cheng C. Y., and Li Y. K. (2008) Structural simulation and protein engineering to convert an endo-chitosanase to an exo-chitosanase. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 21, 561–566 10.1093/protein/gzn033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yaoi K., Kondo H., Hiyoshi A., Noro N., Sugimoto H., Tsuda S., Mitsuishi Y., and Miyazaki K. (2007) The structural basis for the exo-mode of action in GH74 oligoxyloglucan reducing end-specific cellobiohydrolase. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 53–62 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fang X., Yano S., Inoue H., and Sawayama S. (2009) Strain improvement of Acremonium cellulolyticus for cellulase production by mutation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 107, 256–261 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2008.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fujii T., Iwata K., Murakami K., Yano S., and Sawayama S. (2012) Isolation of uracil auxotrophs of the fungus Acremonium cellulolyticus and the development of a transformation system with the pyrF gene. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76, 245–249 10.1271/bbb.110498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fujii T., Koike H., Sawayama S., Yano S., and Inoue H. (2015) Draft genome sequence of Talaromyces cellulolyticus strain Y-94, a source of lignocellulosic biomass-degrading enzymes. Genome Announc. 3, e00014–00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller G. L. (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 31, 426–428 10.1021/ac60147a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. MacIlvaine T. C. (1921) A buffer solution for colorimetric comparison. J. Biol. Chem. 49, 183–186 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cataldi T. R. I., Campa C., and De Benedetto G. E. (2000) Carbohydrate analysis by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection: the potential is still growing. Fresenius. J. Anal. Chem. 368, 739–758 10.1007/s002160000588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kemmer G., and Keller S. (2010) Nonlinear least-squares data fitting in Excel spreadsheets. Nat. Protoc. 5, 267–281 10.1038/nprot.2009.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Strohalm M., Kavan D., Novák P., Volný M., and Havlíček V. (2010) MMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal. Chem. 82, 4648–4651 10.1021/ac100818g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vagin A., and Teplyakov A. (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 10.1107/S0021889897006766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G. W., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bunkóczi G., and Read R. J. (2011) Improvement of molecular-replacement models with Sculptor. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 303–312 10.1107/S0907444910051218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., et al. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Terwilliger T. C., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Afonine P. V., Moriarty N. W., Zwart P. H., Hung L. W., Read R. J., and Adams P. D. (2008) Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 61–69 10.1107/S090744490705024X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Skubák P., Murshudov G. N., and Pannu N. S. (2004) Direct incorporation of experimental phase information in model refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2196–2201 10.1107/S0907444904019079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams C. J., Headd J. J., Moriarty N. W., Prisant M. G., Videau L. L., Deis L. N., Verma V., Keedy D. A., Hintze B. J., Chen V. B., Jain S., Lewis S. M., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Snoeyink J., Adams P. D., et al. (2018) MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 10.1002/pro.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DeLano W. L. (2018) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8.6.0, Schroedinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 55. Frishman D., and Argos P. (1995) Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins 23, 566–579 10.1002/prot.340230412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J., Thompson J. D., and Higgins D. G. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saitou N., and Nei M. (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zuckerkandl E., and Pauling L. (1965) Molecules as documents of evolutionary history. J. Theor. Biol. 8, 357–366 10.1016/0022-5193(65)90083-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kumar S., Stecher G., and Tamura K. (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0. molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.