Abstract

Background

Labour companionship refers to support provided to a woman during labour and childbirth, and may be provided by a partner, family member, friend, doula or healthcare professional. A Cochrane systematic review of interventions by Bohren and colleagues, concluded that having a labour companion improves outcomes for women and babies. The presence of a labour companion is therefore regarded as an important aspect of improving quality of care during labour and childbirth; however implementation of the intervention is not universal. Implementation of labour companionship may be hampered by limited understanding of factors affecting successful implementation across contexts.

Objectives

The objectives of the review were to describe and explore the perceptions and experiences of women, partners, community members, healthcare providers and administrators, and other key stakeholders regarding labour companionship; to identify factors affecting successful implementation and sustainability of labour companionship; and to explore how the findings of this review can enhance understanding of the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and POPLINE K4Health databases for eligible studies from inception to 9 September 2018. There were no language, date or geographic restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis; focused on women’s, partners’, family members’, doulas', providers', or other relevant stakeholders' perceptions and experiences of labour companionship; and were from any type of health facility in any setting globally.

Data collection and analysis

We used a thematic analysis approach for data extraction and synthesis, and assessed the confidence in the findings using the GRADE‐CERQual approach. We used two approaches to integrate qualitative findings with the intervention review findings. We used a logic model to theorise links between elements of the intervention and health and well‐being outcomes. We also used a matrix model to compare features of labour companionship identified as important in the qualitative evidence synthesis with the interventions included in the intervention review.

Main results

We found 51 studies (52 papers), mostly from high‐income countries and mostly describing women's perspectives. We assessed our level of confidence in each finding using the GRADE‐CERQual approach. We had high or moderate confidence in many of our findings. Where we only had low or very low confidence in a finding, we have indicated this.

Labour companions supported women in four different ways. Companions gave informational support by providing information about childbirth, bridging communication gaps between health workers and women, and facilitating non‐pharmacological pain relief. Companions were advocates, which means they spoke up in support of the woman. Companions provided practical support, including encouraging women to move around, providing massage, and holding her hand. Finally, companions gave emotional support, using praise and reassurance to help women feel in control and confident, and providing a continuous physical presence.

Women who wanted a companion present during labour and childbirth needed this person to be compassionate and trustworthy. Companionship helped women to have a positive birth experience. Women without a companion could perceive this as a negative birth experience. Women had mixed perspectives about wanting to have a male partner present (low confidence). Generally, men who were labour companions felt that their presence made a positive impact on both themselves (low confidence) and on the relationship with their partner and baby (low confidence), although some felt anxious witnessing labour pain (low confidence). Some male partners felt that they were not well integrated into the care team or decision‐making.

Doulas often met with women before birth to build rapport and manage expectations. Women could develop close bonds with their doulas (low confidence). Foreign‐born women in high‐income settings may appreciate support from community‐based doulas to receive culturally‐competent care (low confidence).

Factors affecting implementation included health workers and women not recognising the benefits of companionship, lack of space and privacy, and fearing increased risk of infection (low confidence). Changing policies to allow companionship and addressing gaps between policy and practice were thought to be important (low confidence). Some providers were resistant to or not well trained on how to use companions, and this could lead to conflict. Lay companions were often not integrated into antenatal care, which may cause frustration (low confidence).

We compared our findings from this synthesis to the companionship programmes/approaches assessed in Bohren’s review of effectiveness. We found that most of these programmes did not appear to address these key features of labour companionship.

Authors' conclusions

We have high or moderate confidence in the evidence contributing to several of these review findings. Further research, especially in low‐ and middle‐income settings and with different cadres of healthcare providers, could strengthen the evidence for low‐ or very low‐confidence findings. Ahead of implementation of labour companionship, researchers and programmers should consider factors that may affect implementation, including training content and timing for providers, women and companions; physical structure of the labour ward; specifying clear roles for companions and providers; integration of companions; and measuring the impact of companionship on women’s experiences of care. Implementation research or studies conducted on labour companionship should include a qualitative component to evaluate the process and context of implementation, in order to better interpret results and share findings across contexts.

Plain language summary

Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship

What is the aim of this synthesis?

The aim of this Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis was to explore how women, families, and health workers experience women going through labour and childbirth with a support person ('labour companion'). A labour companion may be the woman’s partner, family member, trained supporter (doula), or nurse/midwife. We collected and analysed all relevant qualitative studies to answer this question.

This qualitative evidence synthesis links to another Cochrane Review by Bohren and colleagues from 2017 that assesses the effect of continuous support for women during childbirth. Continuous support improves health and well‐being for women and babies but factors affecting successful implementation are not well understood.

Key messages

Labour companions provide women with information, practical, and emotional support, and can speak up in support of women. Companions can help women have a positive birth experience and need to be compassionate and trustworthy. However, not all women who want a labour companion have one, especially in lower‐resource settings.

What was studied in this synthesis?

We use the term 'labour companionship' to describe support provided to women during labour and childbirth. In high‐income countries, women are often accompanied by family members or a doula. But in health facilities in low‐ and middle‐income countries, women may not be allowed to have any support person, and may go through labour and childbirth alone.

Bohren's review from 2017 shows that supporting women during childbirth has positive effects on women's experiences and on their health. We sought to understand how women, partners, and healthcare providers felt about labour companionship, and what factors might influence women's access to labour companionship.

What are the main findings?

We found 51 studies, mostly from high‐income countries and mostly describing women's perspectives. We assessed our level of confidence in each finding using the GRADE‐CERQual approach. We had high or moderate confidence in many of our findings. Where we only had low or very low confidence in a finding, we have indicated this.

Labour companions supported women in four different ways. Companions gave informational support by providing information about childbirth, bridging communication gaps between health workers and women, and facilitating non‐pharmacological pain relief. Companions were advocates, which means they spoke up in support of the woman. Companions provided practical support, including encouraging women to move around, providing massage, and holding her hand. Finally, companions gave emotional support, using praise and reassurance to help women feel in control and confident, and providing a continuous physical presence.

Women who wanted a companion present during labour and childbirth needed this person to be compassionate and trustworthy. Companionship helped women to have a positive birth experience. Women without a companion could perceive this as a negative birth experience. Women had mixed perspectives about wanting to have a male partner present (low confidence). Generally, men who were labour companions felt that their presence made a positive impact on both themselves (low confidence) and on the relationship with their partner and baby (low confidence), although some felt anxious witnessing labour pain (low confidence). Some male partners felt that they were not well integrated into the care team or decision‐making.

Doulas often met with women before birth to build rapport and manage expectations. Women could develop close bonds with their doulas (low confidence). Foreign‐born women in high‐income settings may appreciate support from community‐based doulas to receive culturally‐competent care (low confidence).

Factors affecting implementation included health workers and women not recognising the benefits of companionship, lack of space and privacy, and fearing increased risk of infection (low confidence). Changing policies to allow companionship and addressing gaps between policy and practice were thought to be important (low confidence). Some providers were resistant to or not well trained on how to use companions, and this could lead to conflict. Lay companions were often not integrated into antenatal care, which may cause frustration (low confidence).

We compared our findings from this synthesis to the companionship programmes/approaches assessed in Bohren’s review of effectiveness. We found that most of these programmes did not appear to address these key features of labour companionship.

How up‐to‐date is this synthesis?

We searched for studies published before 9 September 2018.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of qualitative findings.

| Finding number | Summary of review finding | Studies contributing to the review finding | CERQual assessment (confidence in the findings) | Explanation of CERQual assessment |

| Factors affecting implementation | ||||

| Awareness‐raising among healthcare providers and women | ||||

| 1 | The benefits of labour companionship may not be recognised by providers, women, or their partners. | Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Brüggemann 2014; Coley 2016; Pafs 2016 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence, and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy |

| 2 | Labour companionship was sometimes viewed as non‐essential or less important compared to other aspects of care, and therefore deprioritised due to limited resources to spend on 'expendables'. | Akhavan 2012b; Brüggemann 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Premberg 2011 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and serious concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

| Creating an enabling environment | ||||

| 3 | Formal changes to existing policies regarding allowing companions on the labour ward may be necessary prior to implementing labour companionship models at a facility level. | Abushaikha 2013; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and serious concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

| 4 | In settings where companions are allowed, there can be gaps between a policy or law allowing companionship, and the actual practice of allowing all women who want companionship to have a companion present. | Brüggemann 2014; Kaye 2014 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy, and serious concerns regarding relevance |

| 5 | Providers, women and male partners highlighted physical space constraints of the labour wards as a key barrier to labour companionship as it was perceived that privacy could not be maintained and wards would become overcrowded. | Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Brüggemann 2014; Harte 2016; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding relevance and coherence, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy and methodological limitations |

| 6 | Some providers, women and male partners were concerned that the presence of a labour companion may increase the risk of transmitting infection in the labour room. | Abushaikha 2013; Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance, and serious concerns regarding adequacy |

| Training, supervision, and integration with care team | ||||

| 7 | Some providers were resistant to integrate companions or doulas into maternity services, and provided several explanations for their reluctance. Providers felt that lay companions lacked purpose and boundaries, increased provider workloads, arrived unprepared, and could be in the way. | Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Brüggemann 2014; Horstman 2017; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kaye 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013 | High confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy |

| 8 | In most cases, male partners were not integrated into antenatal care or training sessions before birth. Where they were included in antenatal preparation, they felt that they learned comfort and support measures to assist their partners, but that these measures were often challenging to implement throughout the duration of labour and birth. | Abushaikha 2013; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Chandler 1997; Ledenfors 2016; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance, and serious concerns regarding adequacy |

| 9 | In settings where lay companionship or doula care were available, providers were not well trained on how to integrate the companion as an active or important member of the woman’s support team. | Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kaye 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy |

| 10 | Some doulas felt that they were not well integrated into decision‐making or care co‐ordination by the healthcare providers, and were sometimes ignored by healthcare providers. | Berg 2006; McLeish 2018; Stevens 2011; Torres 2013 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, and serious concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

| 11 | Most healthcare providers believed that having a lay companion support a woman throughout labour and childbirth was beneficial to the woman and worked well when companions were integrated into the model of care. However, when lay companions were not well engaged or integrated, conflict could arise as they may be perceived as an additional burden for healthcare providers to manage their presence, and provide ongoing direction and support. | Brüggemann 2014; Harte 2016; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Maher 2004; Qian 2001 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, relevance, and adequacy |

| 12 | Most midwives believed that doulas played a collaborative role in supporting women during childbirth, and were assets to the team who provided more woman‐centred, needs‐led support. However, some midwives found it difficult to engage as carers with women when doulas were present, as they felt that doulas encroached on their carer role. | Akhavan 2012b; Lundgren 2010; McLeish 2018; Stevens 2011 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy, and serious concerns regarding relevance |

| 13 | Lay companions received little or no training on how to support the woman during labour and childbirth, which made them feel frustrated. | Kululanga 2012; Sapkota 2012 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological considerations and coherence, and serious concerns regarding relevancy and adequacy |

| 14 | Some men felt that they were actively excluded, left out, or not involved in their female partner's care. They were unsure of where they fit in to support the woman, and felt that their presence was tolerated but not necessary. | Bäckström 2011; Chandler 1997; Kaye 2014; Kululanga 2012; Longworth 2011; Somers‐Smith 1999 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, relevance and adequacy |

| Roles that companions play | ||||

| Informational support | ||||

| 15 | Women valued the non‐pharmacological pain relief measures that companions helped to facilitate, including a soothing touch (holding hands, massage and counter pressure), breathing, and relaxation techniques. | Campero 1998; Chapman 1990; Dodou 2014; de Souza 2010; Fathi 2017; Hunter 2012; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Lundgren 2010; McLeish 2018; Sapkota 2013; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999; Thorstensson 2008; Torres 2015 | High confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding adequacy, coherence, and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations |

| 16 | Doulas played an important role in providing information to women about the process of childbirth, duration of labour, and reasons for medical interventions. They bridged communication gaps between clinical staff and women, and facilitated a more actively engaged environment where women were encouraged to ask questions. | Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Berg 2006; Campero 1998; Darwin 2016; Gilliland 2011; Horstman 2017; LaMancuso 2016; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Schroeder 2005; Torres 2013; Torres 2015 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| 17 | Lay companions also played a role in providing informational support to women or acting as the woman's voice during labour and childbirth. This usually took the form of acting as an intermediary by relaying, repeating, or explaining information from the healthcare provider to the woman, and from the woman to the healthcare provider. | Alexander 2014; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Khresheh 2010; Price 2007; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy |

| 18 | Companions played an important role to help facilitate communication between the woman and healthcare providers, including representing the woman's interests and speaking on her behalf when she was unable to do so. They helped to relay information between the woman and healthcare provider, such as asking questions and setting boundaries. | Akhavan 2012b; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Darwin 2016; Gentry 2010; Hardeman 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Khresheh 2010; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; LaMancuso 2016; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Premberg 2011; Price 2007; Stevens 2011; Torres 2015 | Moderate concerns | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| Advocacy | ||||

| 19 | Companions played a role to bear witness to the process of childbirth. They shared the childbirth experience with the woman by being with her, and were viewed as observers who could monitor, reflect, and report on what transpired throughout labour and childbirth, such as witnessing pain, the birth process, and the woman's transformation to motherhood. | Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Dodou 2014; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Longworth 2011; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012 | High confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological considerations, coherence, relevance and adequacy |

| Practical support | ||||

| 20 | Companions provided physical support to women throughout labour and childbirth, such as giving them a massage and holding their hand. Companions encouraged and helped women to mobilise throughout labour or to change positions, such as squatting or standing, and provided physical support to go to the bathroom or adjust clothing. | Afulani 2018; Chandler 1997; Chapman 1990; de Souza 2010; Fathi 2017; Hunter 2012; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; McLeish 2018; Premberg 2011; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013; Torres 2013 | High confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, relevance and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations |

| 21 | Companions played an important role to assist healthcare providers to care for women by observing and identifying potential issues throughout labour and childbirth. | Akhavan 2012b; Alexander 2014; Khresheh 2010; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy |

| 22 | Some healthcare providers and doulas felt that shortcomings in maternity services could be potentially addressed by doulas or lay companions. | Afulani 2018; Akhavan 2012b; Stevens 2011 | Very low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, and serious concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

| Emotional support | ||||

| 23 | Women valued that companions and doulas helped to facilitate their feeling in control during labour and gave them confidence in their abilities to give birth. | Berg 2006; Campero 1998; Chapman 1990; Darwin 2016; Dodou 2014; Fathi 2017; Gilliland 2011; Hunter 2012; Ledenfors 2016; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding adequacy and coherence, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| 24 | Companions often provided emotional support to women through the use of praise and reassurance. They acknowledged the women's efforts and concerns, and provided reinforcement through verbal encouragement and affirmations. | Abushaikha 2012; Alexander 2014; Bäckström 2011; Berg 2006; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; de Souza 2010; Fathi 2017; Gentry 2010; Gilliland 2011; Hardeman 2016; Harte 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Ledenfors 2016; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Premberg 2011; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012; Schroeder 2005; Somers‐Smith 1999; Thorstensson 2008; Torres 2013; Torres 2015 | High confidence | Due to very minor concerns regarding adequacy, minor concerns regarding coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations |

| 25 | The continuous physical presence of someone caring was an important role that companions played, particularly in settings where continuous midwifery care was not available or not practiced. The continuous presence of the companion signalled to the woman the availability of support when needed, and helped to pass the time throughout labour. | Abushaikha 2012; Afulani 2018; Berg 2006; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Campero 1998; Darwin 2016; Dodou 2014; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Lundgren 2010; McLeish 2018; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999; Stevens 2011; Thorstensson 2008; Torres 2015 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| Experiences of companionship | ||||

| Women’s experiences | ||||

| 26 | Women stated different preferences for their desired companion, including their husband or male partner, sister, mother, mother‐in‐law, doula, or a combination of different people. Regardless of which person they preferred, women who wanted a labour companion present during labour and childbirth expressed the need for this person to be a caring, compassionate, and trustworthy advocate. | Abushaikha 2012; Afulani 2018; Akhavan 2012a; Alexander 2014; Berg 2006; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Campero 1998; Dodou 2014; Fathi 2017; Hunter 2012; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Lundgren 2010; Pafs 2016; Price 2007; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013; Somers‐Smith 1999; Torres 2015 | High confidence | Due to very minor concerns regarding coherence, relevance and adequacy, and minor concerns regarding methodological limitations |

| 27 | Women described the desire for a happy and healthy birth for both themselves and their babies. Support provided by doulas and companions paved the way for them to have a positive birth experience, as the support facilitated them to feel safe, strong, confident and secure. | Abushaikha 2012; Abushaikha 2013; Akhavan 2012a; Alexander 2014; Berg 2006; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Campero 1998; Darwin 2016; Dodou 2014; Gilliland 2011; Hunter 2012; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Ledenfors 2016; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; Price 2007; Sapkota 2012; Schroeder 2005; Torres 2015 | High confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, relevance, and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations |

| 28 | Immigrant, refugee, and foreign‐born women resettled in high‐income countries highlighted how community‐based doulas (e.g. someone from their ethnic/religious/cultural community trained as a doula) were an important way for them to receive culturally competent care. | Akhavan 2012a; Hardeman 2016; LaMancuso 2016; Stevens 2011 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance, and serious concerns due to adequacy |

| 29 | Some women were concerned that their male partners would have diminished sexual attraction to them if they witnessed the birth. Likewise, some men believed that it is taboo to see a female partner give birth because of the risk of a loss of sexual interest. | Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Kululanga 2012; Pafs 2016; Sapkota 2012 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, moderate concerns regarding relevance, and serious concerns regarding adequacy |

| 30 | Some women felt embarrassed or shy to have a male partner as a companion present throughout labour and childbirth. | Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Sapkota 2012 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, moderate concerns regarding relevance, and serious concerns regarding adequacy |

| 31 | Women who did not have a companion may view the lack of support as a form of suffering, stress and fear that made their birth experience more challenging. These women detailed experiences of poor quality of care that included mistreatment, poor communication, and neglect that made them feel vulnerable and alone. | Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Campero 1998; Chadwick 2014; Fathi 2017; Khresheh 2010; Pafs 2016 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, and moderate concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

| 32 | Some women described having their male partners present as an essential part of the birth process, which facilitated bonding between the father and the baby, the couple, and as a family. | Abushaikha 2012; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Price 2007 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence, moderate concerns regarding relevance, and serious concerns regarding adequacy |

| 33 | Most women who had a doula present described doulas as motherly, sisterly, or like family, suggesting a high level of relational intimacy. | Berg 2006; Coley 2016; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; McGarry 2016 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy, and serious concerns regarding relevance |

| Male partners' experiences | ||||

| 34 | Male partners had three main motivations for acting as a labour companion for their female partner: curiosity, woman’s request, and peer encouragement, and were in agreement that ultimately it should be the woman’s choice about who is allowed to be present. | Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Chapman 1990; Kululanga 2012; Longworth 2011; Pafs 2016; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence, and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding adequacy |

| 35 | Men who acted as labour companions for their female partners felt that their presence made a positive impact on themselves as individuals. | Kululanga 2012; Sapkota 2012 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological considerations and coherence, and serious concerns regarding relevancy and adequacy |

| 36 | Men who acted as labour companions for their female partners felt that their presence made a positive impact on their relationship with their female partner and the new baby. | Dodou 2014; Kululanga 2012; Sapkota 2012 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological considerations and coherence, and serious concerns regarding relevancy and adequacy. |

| 37 | Men who acted as labour companions for their female partners may feel scared, anxious or helpless when witnessing their partners in pain during labour and childbirth. | Fathi 2017; Kaye 2014; Kululanga 2012; Sapkota 2012 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding methodological considerations and coherence, and serious concerns regarding relevancy and adequacy. |

| 38 | Some lay companions (both male and female) were deeply impacted by witnessing a woman's pain during labour. Observing this pain caused feelings of frustration and fear, as they felt that there was nothing that they could do to help alleviate their pain. | Abushaikha 2013; Chandler 1997; Chapman 1990; Fathi 2017; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kululanga 2012; Sapkota 2012 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and relevance, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy |

| 39 | Some male partners felt that they were not well integrated into the care team or decision‐making. These men felt that their presence was tolerated by healthcare providers, but was not a necessary role. They relied on cues from the woman and healthcare provider for when and how to give support, but were often afraid to ask questions to avoid being labelled as difficult. | Bäckström 2011; Chandler 1997; Kaye 2014; Kululanga 2012; Longworth 2011; Somers‐Smith 1999 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, relevance, and adequacy |

| Doulas’ experiences | ||||

| 40 | Doulas often met with women, and sometimes their partners, prior to the birth to establish a relationship with them. This helped to manage expectations, and mentally and physically prepare the woman and her partner for childbirth. | Akhavan 2012b; Berg 2006; Coley 2016; Darwin 2016; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Lundgren 2010; Shlafer 2015; Stevens 2011; Torres 2015 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| 41 | Doulas believed that one of their key responsibilities was to build rapport and mutual trust with the woman, in order to improve her birth experience. This relationship was foundational for the doulas to give effective support, and for the women to feel comfortable enough to let go. Doulas built rapport by communicating, providing practical support, comforting and relating to the woman. | Berg 2006; Coley 2016; de Souza 2010; Gilliland 2011; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; McGarry 2016; Shlafer 2015; Thorstensson 2008 | Moderate confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy, and moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and relevance |

| 42 | Doulas found that the experience of providing support to women in labour could have a positive personal impact on themselves. Some found that acting as a doula built their self‐confidence, made them feel like they were making a difference, and provided a sense of fulfilment. | Hardeman 2016; Hunter 2012; McGarry 2016; Thorstensson 2008 | Low confidence | Due to minor concerns regarding coherence, moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, and serious concerns regarding relevance and adequacy |

Background

Women have traditionally been attended to by a companion throughout labour and childbirth, but initiatives to increase the number of women giving birth in health facilities have not necessarily respected this tradition. A Cochrane systematic review of interventions concluded that having a labour companion improves outcomes for women, yet this basic, inexpensive intervention is far from universal (Bohren 2017). There is also a global interest in improving the quality of maternal and newborn care, including to “initiate, support and sustain programs designed to improve the quality of maternal health care” (World Health Organization 2014a). This includes a strong focus on respectful care as an essential component of quality of care (World Health Organization 2018). The presence of a labour companion is therefore regarded as an important aspect of improving quality of care during labour and childbirth. In addition to influencing women’s satisfaction with care, providing labour companionship may also influence the social dynamic between the woman and the healthcare provider, including behaviours that could be classified as mistreatment during childbirth.

Following a technical meeting held at the World Health Organization in August 2015, it was noted that implementation of labour companionship may be hampered by a lack of understanding of the factors affecting successful implementation, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). In these settings, qualitative research on labour companionship could provide more in‐depth understanding of factors influencing effective implementation, including shedding light on:

the differences in the nature, degree, acceptability and contextual operation of labour companionship provided by professional labour companions when compared to lay labour companions;

characteristics and features of labour companionship in settings where it is working well and less well, including barriers and facilitators to implementation and sustainability;

women’s perceptions and experiences of labour companionship;

partners’ or other community members’ perceptions and experiences of labour companionship; and

healthcare providers’ perceptions and experiences of labour companionship.

Description of the topic

In the Bohren 2017 intervention review, continuous support is defined as “continuous presence and support during labour and birth”. The person providing the support could have qualifications as a healthcare professional (nurse, midwife), training as a doula or childbirth educator, or be a family member, spouse/partner, friend or stranger with little or no special training in labour support” (Bohren 2017). The terminology of 'continuous support' has been used to describe this type of intervention since the first version of Bohren 2017 was published in 2003, and through six review updates.

In this qualitative evidence synthesis, we use the term 'labour companionship' to describe support provided to a woman during labour and childbirth, in order to cover the full spectrum of contexts and situations in which women may be accompanied and supported during labour. For example, in certain settings, labour companionship may not be allowed 'continuously' throughout labour and childbirth, but may be allowed 'intermittently' (e.g. during labour but not during the birth). In this qualitative evidence synthesis, the person providing labour companionship may be any of the people described in Bohren 2017, including a healthcare professional, doula, childbirth educator, family member, spouse/partner, friend or stranger. For the purposes of this synthesis, a doula refers to a “trained professional who provides continuous physical, emotional and informational support to a mother before, during and shortly after childbirth to help her achieve the healthiest, most satisfying experience possible” (DONA International, 2018). A 'lay companion' refers to a person supporting a woman throughout labour and childbirth who is not a healthcare provider, doula or other trained professional. In practice, a 'lay companion' typically refers to a woman’s partner, family member, or friend.

In many high‐income settings, a woman’s partner, family members, or friends may be encouraged to accompany her throughout her labour and childbirth. In settings where a woman has a private labour suite, she may be able to have several people supporting her through labour and childbirth. She may also be able to hire a doula to provide additional support. In contrast, health facilities in LMICs or other contexts that prioritise the medicalisation of childbirth may not allow women to have a support person present in the labour ward. In these settings, there also may not be one‐to‐one maternity care models. Thus, women may typically go through labour and childbirth without supportive care from either a lay companion or a healthcare professional.

Why is it important to do this synthesis?

The Bohren 2017 intervention review measured the effectiveness of continuous support during labour, from 26 studies involving 15,858 women in 17 different countries. Women allocated to continuous support were more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth (average risk ratio (RR) 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.04 to 1.12; 21 studies, 14,369 women; low‐quality evidence); and less likely to:

report negative ratings of or feelings about their childbirth experience (average RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.79; 11 studies, 11,133 women; low‐quality evidence);

use any intrapartum analgesia (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.96; 15 studies, 12,433 women);

have a caesarean birth (average RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88; 24 studies, 15,347 women; low‐quality evidence);

have an instrumental vaginal birth (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96; 19 studies, 14,118 women),

have regional analgesia (average RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99; 9 studies, 11,444 women); and

have a baby with a low five‐minute Apgar score (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.85; 14 studies, 12,615 women).

In addition, their labours were shorter (mean difference (MD) −0.69 hours, 95% CI −1.04 to −0.34; 13 studies, 5429 women; low‐quality evidence). Bohren 2017 was not able to combine data from two studies for postpartum depression included in the review due to differences in women, hospitals and care providers. There was no apparent impact on other intrapartum interventions, maternal or neonatal complications, such as admission to special care nursery (average RR 0.97, 95%CI 0.76 to 1.25; 7 studies, 8897 women; low quality evidence), and exclusive or any breastfeeding at any time point (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.16; 4 studies, 5584 women; low‐quality evidence; Bohren 2017).

While Bohren 2017 concluded that providing continuous support to women was promising to improve women’s birth experiences and clinical outcomes, implementation of this intervention remains substandard. The level of organisation and support required to restructure maternity services to allow the presence of companions is complex and requires a better understanding of the factors that may influence success and sustainability. Understanding the values, preferences, and knowledge of key stakeholders, as well as the feasibility and applicability of the intervention for diverse contexts and health systems is critical for successful implementation. Bohren 2017 was not designed to answer these types of questions; thus it has been acknowledged that a qualitative evidence synthesis could address these questions and better understand factors that may affect implementation. Synthesising the qualitative evidence can allow us to explore similarities and differences across contexts, and better understand how the structure and components of the intervention may influence health and well‐being outcomes.

A previous literature review by Kabakian‐Khasholian 2017 synthesised factors affecting implementation of continuous support from the studies included in the 2013 version of Bohren 2017 (Hodnett 2013), and supplemented with 10 qualitative studies conducted alongside the studies. We believed that in addition to the 10 qualitative studies conducted alongside the studies, that there would be meaningful qualitative evidence on labour companionship conducted outside of the context of a study. Therefore, we decided to search for qualitative studies that explored labour companionship either alongside or outside of the context of a study.

This review is one of a series of reviews that aimed to inform the World Health Organization’s (WHO) “Recommendations for intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience” World Health Organization 2018. Labour companionship is recommended in four WHO guidelines World Health Organization 2012; World Health Organization 2014b; World Health Organization 2015; World Health Organization 2018.

Objectives

The overall objective of the review is to describe and explore the perceptions and experiences of women, their partners, community members, healthcare providers and administrators, and other key stakeholders regarding labour companionship. The review has the following objectives:

to identify women’s, partners’, community members’, healthcare providers’ and administrators’, and other key stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences regarding labour companionship in health facilities;

to identify factors affecting successful implementation and sustainability of labour companionship; and

to explore how the findings of this review can enhance understanding of the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions (Bohren 2017).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this synthesis

Types of studies

We included primary studies that used qualitative methods for data collection (e.g. interviews, focus group discussions, observations), and that used qualitative methods for data analysis (e.g. thematic analysis, grounded theory). We excluded primary studies that collected data using qualitative methods but did not perform a qualitative analysis (e.g. open‐ended survey questions where responses are analysed using descriptive statistics). We included mixed‐methods studies when it was possible to extract data resulting from qualitative methods. Qualitative studies did not need to be linked to effectiveness studies included in the related Cochrane Review (Bohren 2017), and did not need to be linked to an intervention.

Topic of interest

The phenomena of interest in this review are the perceptions and experiences of labour companionship during childbirth in health facilities, of women, partners, community members, healthcare providers and administrators, and other key stakeholders. This includes factors that may influence the feasibility, acceptability and sustainability of implementing a labour companionship intervention.

We included studies that focused on the perceptions and experiences of:

women, including those who have had an experience of labour companionship and those who have not;

partners or other community members who have provided labour support or could potentially provide labour support in the future;

all cadres of healthcare providers (e.g. doctors, nurses, midwives, lay health workers, doulas) who are involved in providing healthcare services to women; and

other relevant stakeholders involved in providing or organising care, including administrators and policy‐makers.

We included studies of labour companionship in any country and in any type of health facility (e.g. health clinics, hospitals, midwife‐led clinics). We were able to potentially include studies published in English, French, Spanish, Turkish, and Norwegian, based on the language abilities of the review team. Additional languages will be included in future updates of this review if we can identify appropriate translators.

Search methods for the identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases for eligible studies from inception to 9 September 2018:

MEDLINE Ovid

CINAHL EbscoHost; and

POPLINE K4Health.

We developed search strategies using guidelines developed by the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group for searching for qualitative evidence (Noyes 2011; see Appendix 1 for the search strategies). We chose these databases as we anticipated that they would provide the highest yield of relevant results based on preliminary, exploratory searches. There were no language, date or geographic restrictions for the search.

Searching other sources

In addition to database searching, we searched references of all included studies and other key references, e.g. references identified in Bohren 2017. We used OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu) to search for relevant grey literature. We contacted key researchers working in the field for additional references or unpublished materials.

Data collection, management and synthesis

Selection of studies

We exported titles and abstracts identified through the database searches to EndNote, and removed duplicates. Two independent review authors assessed each record for eligibility for inclusion according to predefined criteria. We excluded references that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

We retrieved full‐text articles for studies included after title and abstract screening. Two independent review authors assessed each full text for eligibility for inclusion according to predefined criteria. We resolved any disagreements between review authors through discussion or by involving a third review author. If necessary, we contacted study authors for more information to determine study eligibility.

Translation of languages other than English

For studies that were not published in a language that could be understood by the review authors (e.g. in languages other than English, French, Spanish, Turkish and Norwegian), the abstract was subject to initial translation through open source software (Google Translate). If this indicated inclusion, then we sought support through our research networks to translate the full text. Where this was not possible, we listed the study as awaiting classification to ensure transparency in the review process (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Data extraction

We extracted data from the included studies using an Excel form designed for this review. This form included information about the study setting, sample characteristics, objectives, guiding framework, study design, data collection and analysis methods, qualitative themes, qualitative findings, supporting quotations, conclusions, and any relevant tables, figures or images.

Management and synthesis

We used a thematic synthesis approach, as described by Thomas and Harden (Thomas 2008). Thematic synthesis is a useful approach to analyse data from qualitative evidence syntheses exploring people’s perspectives and experiences, acceptability, appropriateness, and factors influencing implementation (Thomas 2008). This is comprised of familiarisation with and immersion in the data, free line‐by‐line coding of the findings of primary studies, organisation of free codes into related themes and development of descriptive themes, and development of analytical themes and interpretations to generate further concepts, understandings and hypotheses (Thomas 2008). We used a modified SURE framework (SURE Collaboration 2011), as an a priori framework to help identify and categorise barriers and facilitators to implementing labour companionship as an intervention (Glenton 2013). The SURE framework provided us with a comprehensive list of factors that could influence the implementation of labour companionship, and helped to integrate the findings of this synthesis with the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions, Bohren 2017. The review authors selected an article that was highly relevant to the review question, and used this article as the basis for the code list, complemented by elements of the SURE framework. First, we structured the codes as 'free' codes with no established link between them. Then we tested these codes on a further three articles, to determine if and how well the concepts translated from one study to another. This further developed the codebook, and we added new codes as necessary. The review authors sought similarities and differences between the codes and grouped the codes according to a hierarchical structure. As new codes arose throughout the analysis process, we revisited studies already coded to determine if the new codes applied or not. Two review authors coded the data, and worked as a team to generate analytical themes. We coded included studies using Atlas.ti software. This facilitated the analysis as the review team developed primary document families to organise groups of studies based on common attributes. We also used it to restrict code‐based searches, to filter coding outputs and to assist in subgroup analyses. For example, primary document families included: type of participant (midwife, doctor, healthcare administrator, woman); geographical location (regional and country‐specific); country income level (high, middle, low); type of labour companion described (doula, health worker, companion of choice, family member, partner); and type of qualitative study (associated with an intervention or stand‐alone study). This allowed the review team to hypothesise what factors shape the perceptions and experiences of women, healthcare providers and administrators.

Assessment of the methodological limitations in included studies

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies must have used qualitative methods for data collection and data analysis. We used an adaptation of the CASP tool (www.casp‐uk.net to appraise the quality of included studies, and included the following domains: aims, methodology, design, recruitment, data collection, data analysis, reflexivity, ethical considerations, findings, and research contribution. Two independent review authors critically appraised the included studies using this form. We resolved any disagreements between review authors through discussion or by involving a third review author. Critical appraisal is a component of the assessment of confidence for each review finding; we did not use critical appraisal as a basis for exclusion.

Assessment of confidence in the synthesis findings

We used the CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to assess our confidence in the review findings (Colvin 2018; Glenton 2018; Lewin 2018a; Lewin 2018b; Munthe‐Kaas 2018; Noyes 2018). This approach, building on the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2017), and the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2017), for Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions, is becoming the standard to assess confidence in the findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (Ames 2017; Bohren 2015a; Colvin 2013; Lewin 2015; Munabi‐Babigumira 2017; Odendaal 2015).The CERQual approach assesses the following four concepts (Lewin 2018a).

Methodological limitations of included studies: the extent to which there are concerns about the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed evidence to an individual review finding. Confidence in a finding may be lowered by substantial methodological limitations.

Coherence of the review finding: an assessment of how clear and cogent the fit is between the data from the primary studies and the review finding that synthesises the data. 'Cogent' refers to a well‐supported or compelling fit. Variations in data across the included studies without convincing and cogent explanations may lower the confidence in a review finding.

Adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding. Confidence in a finding may be lowered if a finding is supported by results from only one or a few of the included studies, or when the data supporting a finding are very thin.

Relevance of the included studies to the review question: the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question. Confidence in a finding may be lowered when contextual issues in a primary study used to support a review finding are different to the context of the review question.

The above assessments resulted in an assessment of the overall confidence in each review finding as high, moderate, low or very low. Qualitative review findings and CERQual assessments are presented in Table 1, and as a more detailed evidence profile in Appendix 2 that summarises the finding, overall confidence assessment, and rationale for assessment of each finding.

Summary of qualitative findings table

Our findings are presented in the 'Summary of qualitative findings' table. The table provides an assessment of confidence in the evidence, as well as an explanation of this assessment, based on the GRADE‐CERQual approach (Lewin 2018a; Lewin 2018b).

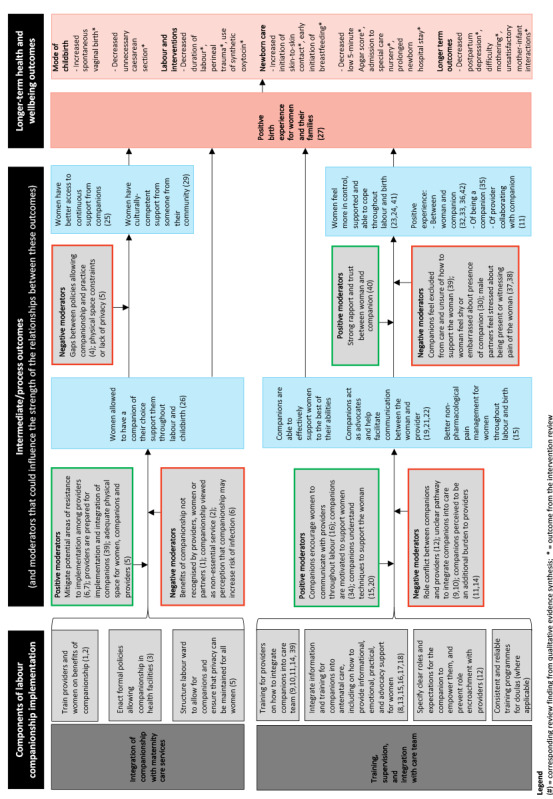

Linking the synthesised qualitative findings to a Cochrane intervention review

One of the objectives of this qualitative evidence synthesis was to better explain and contextualise the findings from the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions, Bohren 2017, and potentially identify hypotheses for future subgroup analyses. We conducted this qualitative evidence synthesis in parallel to the update of Bohren 2017, but we have presented the methods and results as an independent review. Integrating findings from intervention and qualitative reviews is an emerging methodological area, and there are no agreed methods for how to conduct this type of analysis. We used two methods to integrate the synthesised qualitative findings with the Cochrane intervention review: a logic model and a matrix model.

Logic model

We used methods similar to other Cochrane Reviews (see Glenton 2013), to develop a logic model to link qualitative findings for labour companionship to outcomes described in the intervention review, Bohren 2017. The aim of this logic model was not necessarily to demonstrate causal links between elements of the intervention or programme and health and well‐being outcomes. Rather, we used the logic model to depict theories and assumptions about the links, based on the evidence in both reviews and more broadly. We depicted the logic model as a logical flow from components of the labour companionship programme, to intermediate or process outcomes, and resulting in longer‐term health and well‐being outcomes identified in Bohren 2017. Two review authors (MAB and ÖT) reviewed the 'Summary of qualitative findings' table and organised these findings into logical chains of events that may lead to the outcomes reported in Bohren 2017. First, we categorised each finding from the qualitative synthesis and outcome from Bohren 2017 as either:

a component of the companionship programme (qualitative evidence synthesis);

an Intermediate or process outcome (qualitative evidence synthesis);

longer‐term health and well‐being outcomes (Bohren 2017 and qualitative evidence synthesis); or

a moderator (positive or negative), that could influence the relationship between a programme component and intermediate, process, or longer‐term outcomes (qualitative evidence synthesis).

We used an iterative process to develop the chains of events, and in some cases, we used imputation to categorise the findings and outcomes as components, outcomes, and moderators. We sometimes rephrased 'negative' qualitative findings as 'positive' findings for the programme components and intermediate or process outcomes to create a more logical flow. For example, one qualitative finding found that women and providers often were unaware of the benefits of labour companionship, but we rephrased the programme component as, “train women and providers on the benefits of companionship”. To improve transparency of this process, within the logic model, the numbers in parentheses refer to the reference number of the relevant finding from the 'Summary of qualitative findings' table.

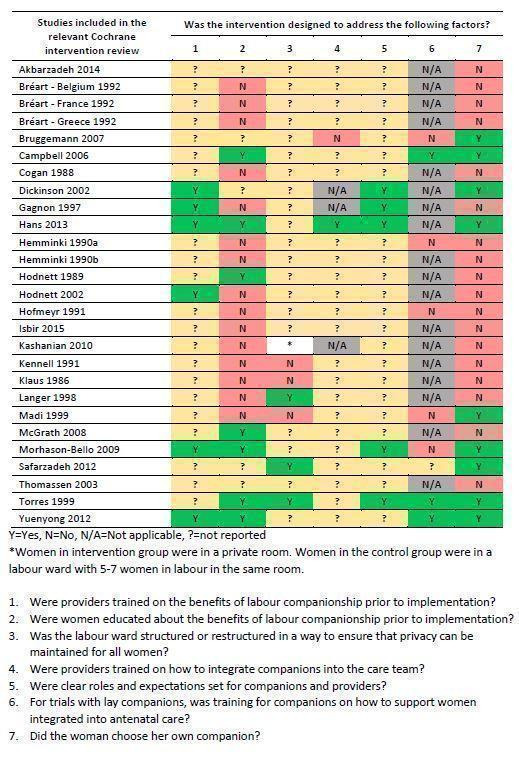

Matrix model

We used a matrix‐model approach similar to Candy 2011 and Ames 2017. Two authors (MAB and ÖT) used a matrix‐model approach to create a comparative table that explored whether the interventions included in the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions (Bohren 2017), contained the features of labour companionship that women, partners and providers identified as important in the qualitative evidence synthesis. To create the matrix, we first reviewed the 'Summary of qualitative findings' table to identify the features of labour companionship that key stakeholders viewed as important moderators (positive or negative). We organised these features into groups and developed seven questions reflecting these issues. Each question could be answered as yes, no, not reported or not applicable, to reflect whether this feature of companionship was addressed in the intervention.

Were providers trained on the benefits of labour companionship prior to implementation?

Were women educated about the benefits of labour companionship prior to implementation?

Was the labour ward structured or restructured in a way to ensure that privacy can be maintained for all women?

Were providers trained on how to integrate companions into the care team?

Were clear roles and expectations set for companions and providers?

For studies with lay companions, was training for companions on how to support women integrated into antenatal care?

Did the woman choose her own companion?

We created a table listing the seven questions and assessed whether the studies included Bohren 2017 reflected these features.

Review author reflexivity

The perspectives of the review authors regarding subject expertise, employment, perspectives of labour companionship, and other background factors may affect the manner in which we collect, analyse and interpret the data. At the outset of this review, all review authors believed that labour companionship was valuable to improve women’s experiences of care, but that critical barriers exist to successful implementation of labour companionship, particularly in LMICs. In many contexts of childbirth in health facilities, the provision of clinical procedures and assessments is considered the pinnacle of care, and women’s experiences of care, including labour companionship and respectful care, are deprioritised. To minimise the risk that our perspectives as authors influence the analysis and interpretation, we used refutational analysis techniques, such as exploring and explaining contradictory findings between studies. We accounted for these differences, and any other issues that may have contributed to the interpretation of the review findings, by describing it in a 'Reflexivity' section when publishing the protocol and full review.

Results

Results of the search

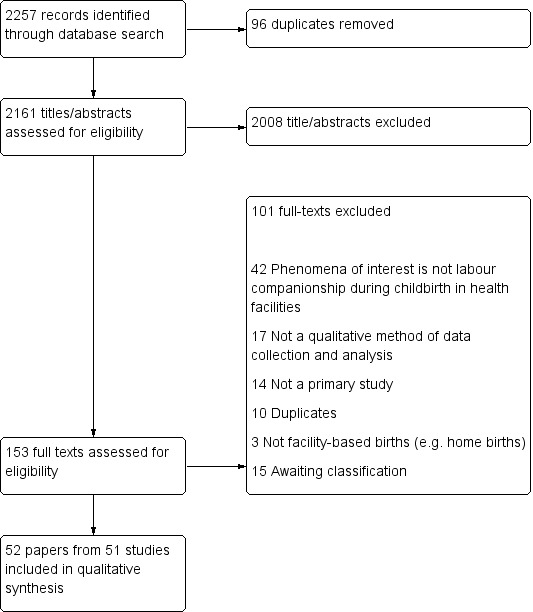

We identified 52 papers from 51 studies published on or before 9 September 2018 that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and are included in this synthesis. Figure 1 depicts the flow of studies.

1.

Study flow diagram

Description of studies

Study participants

Participants in the included studies included a mix of perspectives of women, healthcare providers (midwives, nurses, and doctors), male partners, and doulas (note: no studies included the perspectives of women or partners in non‐heterosexual relationships). Fifteen of the included studies were from the perspectives of women only, four were healthcare providers only, 10 were male partners only, five were doulas only, and 18 were mixed perspectives. The Characteristics of included studies outlines the type of participants and study design for each included study.

Type of labour companion and model of care

Different types of companions supported women at different times throughout pregnancy and childbirth. Twenty‐seven of the included studies had lay companions providing support to women, which was typically a male partner (18 studies: Abushaikha 2012; Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Bäckström 2011; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Chandler 1997; Chapman 1990; Harte 2016; Kaye 2014; Kululanga 2012; Ledenfors 2016; Longworth 2011; Pafs 2016; Premberg 2011; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999), a female companion such as a sister, mother, mother‐in‐law, or friend ( studies: Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Fathi 2017; Harte 2016; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010). Five studies specified that the lay companion was anyone who the woman chose (Brüggemann 2014) or did not specify who the lay companion was (Dodou 2014; Maher 2004; Price 2007; Shimpuku 2013). Twenty‐three of the included studies described support provided by doulas (Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Berg 2006; Campero 1998; Coley 2016; Darwin 2016; de Souza 2010; Gentry 2010; Gilliland 2011; Hardeman 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Lagendyk 2005; LaMancuso 2016; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Schroeder 2005; Shlafer 2015; Stevens 2011; Torres 2013; Torres 2015). One included study (Thorstensson 2008), described support provided to women by female student midwives whose sole responsibility was to provide continuous support (e.g. no concurrent clinical responsibilities). Two included studies described women’s desire to have companionship from a male partner, friend or relative, and the experience of lacking this type of support (Afulani 2018; Chadwick 2014).

Thirty‐eight of the included studies described companionship provided only during labour and childbirth, for example, from admission to the health facility for labour, throughout childbirth and early postpartum periods (Abushaikha 2012; Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Alexander 2014; Bäckström 2011; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Brüggemann 2014; Campero 1998; Chadwick 2014; Chandler 1997; Chapman 1990; Dodou 2014; de Souza 2010; Fathi 2017; Gilliland 2011; Hardeman 2016; Harte 2016; Horstman 2017; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kaye 2014; Khresheh 2010; Kululanga 2012; LaMancuso 2016; Ledenfors 2016; Longworth 2011; Lundgren 2010; Maher 2004; Pafs 2016; Premberg 2011; Price 2007; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013; Shlafer 2015; Somers‐Smith 1999; Thorstensson 2008). Twelve of the included studies described an extended model of companionship with doulas, that included support during the pregnancy and/or postpartum periods (Berg 2006; Coley 2016; Darwin 2016; Gentry 2010; Hunter 2012; Lagendyk 2005; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Schroeder 2005; Stevens 2011; Torres 2013; Torres 2015). One study did not specify the timing of doula support (Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006).

Most studies did not have a description of the background or training doulas had in order to practice. Only six studies described doula training or certification programmes (Coley 2016; Lagendyk 2005; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Shlafer 2015), which varied across contexts. Doulas in a study conducted by Lundgren 2010 in Sweden met seven times for a course about birth and breastfeeding. Lagendyk 2005 described training for doulas working in both a hospital and community setting in Canada. In the hospital setting, doulas completed an unspecified certified doula training course for 14 hours and attended an unspecified number of births with a more experienced doula (Lagendyk 2005). In the community setting, doulas completed a 12‐hour training course and attended two births with an experienced volunteer (Lagendyk 2005). A study on doula support for incarcerated women by Shlafer 2015 in the USA describes that doulas were trained and certified by DONA International, as well as receiving additional training by the Department of Corrections, Human Subject Research, and 14 hours of continuing education per year. In the UK, McGarry 2016 described that doulas undertook training and mentoring through a website (www.doulatraining.org), worked alongside a mentor for six months to two years, attended a minimum of four births, and passed a formal assessment interview. Coley 2016 described a process where volunteers participated in training certified by DONA International and participated in three births in the USA. McLeish 2018 described a 90‐hour training programme for doulas that led to accredited qualification, in addition to ongoing support and supervision from a project co‐ordinator.

Setting

Five studies were conducted in five low‐income countries: Uganda (Kaye 2014), Malawi (Kululanga 2012), Rwanda (Pafs 2016), Nepal (Sapkota 2012), and Tanzania (Shimpuku 2013). Thirteen studies were conducted in 11 middle‐income countries: Syria (Abushaikha 2012; Abushaikha 2013), Ghana (Alexander 2014), Brazil (Brüggemann 2014; Dodou 2014; de Souza 2010), Mexico (Campero 1998), South Africa (Chadwick 2014), , Jordan (Khresheh 2010), Kenya (Afulani 2018), Iran (Fathi 2017), and China (Qian 2001); and one multi‐country study conducted in Syria, Egypt and Lebanon (Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015). Thirty‐three studies were conducted in six high‐income countries: Sweden (Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Bäckström 2011; Berg 2006; Ledenfors 2016; Lundgren 2010; Premberg 2011; Thorstensson 2008), Finland (Bondas‐Salonen 1998), Canada (Chandler 1997; Lagendyk 2005; Price 2007), USA (Chapman 1990; Coley 2016; Gentry 2010; Hardeman 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; LaMancuso 2016; Schroeder 2005; Shlafer 2015; Torres 2013; Torres 2015), United Kingdom (Darwin 2016; Longworth 2011; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Somers‐Smith 1999), and Australia (Harte 2016; Maher 2004; Stevens 2011), and one multi‐country study conducted in the USA and Canada (Gilliland 2011). Of the 33 studies conducted in high‐income countries, 21 studies focused on doula models of companionship (Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Berg 2006; Coley 2016; Darwin 2016; Gentry 2010; Gilliland 2011; Hardeman 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Lagendyk 2005; LaMancuso 2016; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Schroeder 2005; Shlafer 2015; Stevens 2011; Torres 2013; Torres 2015).

Seven studies were conducted in Africa (Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Chadwick 2014; Kaye 2014; Kululanga 2012; Pafs 2016; Shimpuku 2013); two in Asia (Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012); 14 in Europe (Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Bäckström 2011; Berg 2006; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Darwin 2016; Ledenfors 2016; Longworth 2011; Lundgren 2010; McGarry 2016; McLeish 2018; Premberg 2011; Somers‐Smith 1999; Thorstensson 2008); five in the Middle East (Abushaikha 2012; Abushaikha 2013; Fathi 2017; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010); 17 in North America (Campero 1998; Chandler 1997; Chapman 1990; Coley 2016; Gentry 2010; Gilliland 2011; Hardeman 2016; Horstman 2017; Hunter 2012; Koumouitzes‐Douvia 2006; Lagendyk 2005; LaMancuso 2016; Price 2007; Schroeder 2005; Shlafer 2015; Torres 2013; Torres 2015); three in South America (Brüggemann 2014; Dodou 2014; de Souza 2010); and three in Oceania (Harte 2016; Maher 2004; Stevens 2011).

Thirteen studies were conducted alongside an intervention or as an evaluation of an intervention or programme (Akhavan 2012a; Akhavan 2012b; Campero 1998; Coley 2016; Darwin 2016; Gentry 2010; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Khresheh 2010; Lagendyk 2005; LaMancuso 2016; McGarry 2016; Schroeder 2005; Shlafer 2015), and 39 studies were stand‐alone qualitative studies (not attached to an intervention, evaluation, or programme).

Critical appraisal of included studies

Detailed critical appraisals can be found in Appendix 3. Fifty‐one of the included studies were published in peer‐reviewed journals, which might impose word limits that are not well suited for comprehensively reporting qualitative research (one included study is a full doctoral dissertation (Chapman 1990)). Across all studies, there was generally poor reporting of recruitment strategies, researcher reflexivity, healthcare context, and data analysis methods. All studies had at a minimum a brief description about the participants, sampling, data collection and analysis methods. Most studies used interviews or focus group discussions, with only a few studies using other qualitative methods of data collection such as participant observation. Reviewer concerns regarding a lack of rich data and thick description of study methodology (depth and breadth) may be attributed to word limits set by journals.

Confidence in the findings

Out of 42 review findings, we used the CERQual approach to grade seven review findings as high confidence, 18 as moderate confidence, and 17 as low or very low confidence (Table 1). The explanation for each CERQual assessment is shown in the evidence profile in Appendix 2.

Themes and findings identified in the synthesis

From the thematic synthesis, we developed 10 overarching themes, which we organised under three domains using the following structure:

-

Factors affecting implementation

Awareness‐raising among healthcare providers and women

Creating an enabling environment

Training, supervision and integration with care team

-

Companion roles

Informational support

Advocacy

Practical support

Emotional support

-

Experiences of companionship

Women’s experiences

Male partners’ experiences

Doulas’ experiences

We explore each review finding under these themes and domains in depth in the following sections. At the end of the results section, we bring together the results of this qualitative evidence synthesis and the related Cochrane systematic review of interventions (Bohren 2017).

Findings

In the sections below, we report each review finding and provide a link to the CERQual evidence profile table supporting the assessment of confidence in that finding (Appendix 2). For each finding, we start with a short, overall summary and then present the detailed results.

Factors affecting implementation

Awareness‐raising among healthcare providers and women

Finding 1

The benefits of labour companionship may not be recognised by providers, women, or their partners (moderate confidence; Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Alexander 2014; Brüggemann 2014; Coley 2016; Pafs 2016). Some providers viewed companionship as a low priority in their setting because of the lack of clear benefit to the woman (Brüggemann 2014). Some women and male partners believed that the partner was unable to do anything to help the woman during labour (Abushaikha 2013; Alexander 2014). When potential tasks or responsibilities for the labour companion were identified (e.g. holding her hand, rubbing her back, encouraging her), it was perceived that this was the role of the clinical staff or that the woman could persevere without this support (Abushaikha 2013; Alexander 2014; Coley 2016).

Finding 2

Labour companionship was sometimes viewed as non‐essential or less important compared to other aspects of care, and therefore deprioritised due to limited resources to spend on 'expendables' (low confidence; Akhavan 2012b; Brüggemann 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Premberg 2011). For example, some health facilities required labour companions to wear hospital‐issued clothing, but clothing for labour companions may not always be available (Brüggemann 2014). Where labour companions were allowed, health facilities faced difficulties to provide adequate material resources, such as bed or chair space (Brüggemann 2014; Premberg 2011).

Creating an enabling environment

Finding 3

Formal changes to existing policies regarding allowing companions on the labour ward may be necessary prior to implementing labour companionship models at a facility level (low confidence; Abushaikha 2013; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015). When policies are changed, healthcare providers of all levels should be aware of the new policies and how to comply with them in their practice (Abushaikha 2013). Policy changes should also be communicated to women and their families, in order to manage their expectations for the labour and childbirth (Abushaikha 2013; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015).

Finding 4

In settings where companions are allowed, there can be gaps between a policy or law allowing companionship, and the actual practice of allowing all women who want companionship to have a companion present (low confidence; Brüggemann 2014; Kaye 2014). In Uganda and Brazil, not all women were allowed to have companions because of congested labour wards and concerns about privacy if the companion was male (Brüggemann 2014; Kaye 2014). In Brazil, by law, companionship is allowed for all women, but some healthcare providers may not allow the woman to have a companion present, for example if she does not have adequate insurance, if the companion appears unprepared, or because of a fear of being 'supervised' by the companion (Brüggemann 2014).

Finding 5

Providers, women and male partners highlighted physical space constraints of the labour wards as a key barrier to labour companionship as it was perceived that privacy could not be maintained and wards would become overcrowded (moderate confidence; Abushaikha 2013; Afulani 2018; Brüggemann 2014; Harte 2016; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013). Labour wards often had open floor plans, possibly with only a curtain to separate beds (Abushaikha 2013; Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001; Sapkota 2012; Shimpuku 2013). In some cases, women were allowed only to have a female companion, in order to protect the privacy of other women, thus restricting her choices (Afulani 2018; Brüggemann 2014).

Finding 6

Some providers, women and male partners were concerned that the presence of a labour companion may increase the risk of transmitting infection in the labour room (low confidence; Abushaikha 2013; Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001). Although acknowledging that there was no evidence suggesting that companions increase the risk of spreading infection (Brüggemann 2014), it was believed that the presence of an additional non‐clinical person may threaten the sterility of the labour room (Brüggemann 2014; Abushaikha 2013; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Qian 2001).

Training, supervision, and integration with care team

Finding 7

Some providers were resistant to integrate companions or doulas into maternity services, and provided several explanations for their reluctance.Providers felt that lay companions lacked purpose and boundaries, increased provider workloads, arrived unprepared, and could be in the way (high confidence; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Brüggemann 2014; Horstman 2017; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kaye 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013). Some providers were also concerned that they could be evaluated unfairly by companions who did not understand the physiology of birth and potential interventions (Brüggemann 2014). Doulas were not always perceived to be a contributing member of the team, and may be viewed hostilely as 'anti‐medical establishment' or as a threat to the role of midwives or nurses (Horstman 2017; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013).

Finding 8

In most cases, male partners were not integrated into antenatal care or training sessions before birth.Where male partners were included in antenatal preparation, they felt that they learned comfort and support measures to assist their partners, but that these measures were often challenging to implement throughout the duration of labour and birth (low confidence; Abushaikha 2013; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Chandler 1997; Ledenfors 2016; Sapkota 2012; Somers‐Smith 1999). Male involvement during pregnancy also helped them to feel more engaged and able to participate in and interact with healthcare services (Abushaikha 2013; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Sapkota 2012).

Finding 9

In settings where lay companionship or doula care were available, providers were not well trained on how to integrate the companion as an active or important member of the woman’s support team (moderate confidence; Bondas‐Salonen 1998; Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Kaye 2014; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013). This could lead to conflict between the provider, companion/doula and the woman, or feeling that the companion/doula was “in the way,” "evaluating" the provider, or "taking over" the role of the provider (Brüggemann 2014; Kabakian‐Khasholian 2015; Lagendyk 2005; Torres 2013). In contexts where there is a more technocratic or less woman‐centred model of maternity care, women’s needs (including companionship) may be deprioritised in lieu of institutional routines, further exacerbating a potential point of conflict (Brüggemann 2014).

Finding 10