Abstract

A 60-year-old male presented with an increasingly painful and swollen phthisical eye. Enucleation revealed a large mass obliterating the eye with extension into the adjacent extraocular muscle. Histologic examination showed high-grade osteosarcoma. Systemic work-up showed no disease elsewhere, and a diagnosis of orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma was rendered. Complete resection was not possible, and neoadjuvant radiation was given. The patient subsequently developed pulmonary metastasis and died of disease 5 months after initial diagnosis. Given the highly aggressive nature of this malignancy, raising awareness that extraskeletal osteosarcoma may arise in the background of phthisis bulbi will facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Enucleation, Phthisis bulbi, Osteosarcoma, Intraocular neoplasms

Established Facts

Phthisical eyes are known to harbor neoplasms in a small percentage of cases.

The majority of the tumors arising in phthisical eyes are uveal melanomas.

Novel Insights

This is the second reported case of osteosarcoma arising in a human eye with phthisis bulbi.

This case raises the possibility of a malignant transformation of metaplastic bone seen in the setting of phthisis bulbi.

Introduction

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is a rare but aggressive mesenchymal tumor in which the malignant tumor cells produce osteoid matrix. There are 5 prior reports involving the orbit arising in a variety of clinical settings, including prior irradiation. We report the second case of extraskeletal osteosarcoma arising in phthisis bulbi.

Case Report

A 60-year-old male with a phthisical left eye, the result of a golfing accident at age 11 causing immediate unilateral loss of vision, presented for routine eye examination. At the visit, the patient reported a several-month history of decreased vision in his right eye. The right eye exam was without abnormalities (anterior segment, fundus, and movements) except for the refraction. The cornea of the left eye was opacified, and the pupil and fundus were not well-visualized. The intraocular pressure was 18 and 15 mm Hg in the right and left eye, respectively. It was noted at that time that the patient was wearing a cosmetic painted contact lens over the left phthisic eye that was faded in color. He was prescribed corrective glasses for the right eye and a new cosmetic contact lens on the left. Furthermore, the recommendation was made for the patient to see a retina specialist for examination of the left eye.

The patient returned for 4 subsequent appointments over the next 4 months regarding the cosmetic contact lens fitting, and no ocular changes were noted. On the day of the final fitting, the patient complained that his left eye had been red and irritated for the past week. On external examination, the left eye had dilated and prominent conjunctival blood vessels with chemosis temporally. There was no corneal ulceration. Since the intraocular pressure was markedly elevated, the patient was referred to a glaucoma specialist who prescribed acetazolamide slow-release capsules and Combigan drops in an attempt to mitigate the rising ocular pressure. The patient was again advised to seek consultation with a vitreoretinal surgeon to evaluate his buckle placement, a potential etiology for his symptoms, and undergo a B-scan, but he did not follow through with these recommendations.

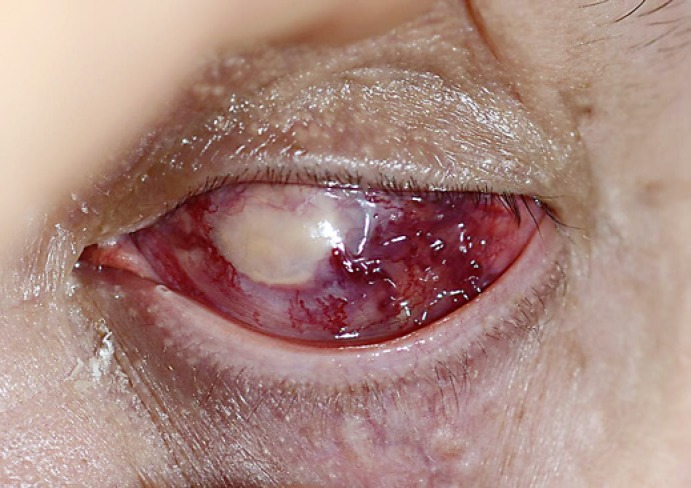

Despite 3 additional months of treatment with glaucoma medications, the symptoms persisted and the possibility of a neoplastic process involving his phthisical eye was raised. The patient agreed to follow-up for further evaluation in a couple of months after an already planned vacation. However, he returned within 2 weeks with increasing pain and ocular redness (Fig. 1); therefore, enucleation was scheduled.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph taken on the day of consultation prior to the enucleation showing the left eye with marked conjunctival congestion, abnormal vasculature, and firmness of the globe.

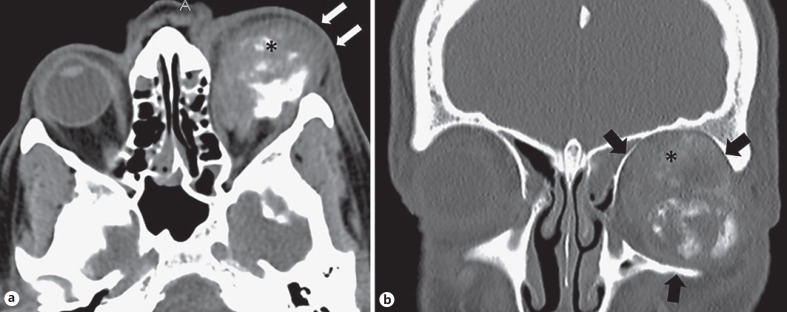

On the day of the surgery, the surgeon noticed marked proptosis and ordered a preoperative orbital CT which revealed a large heterogeneous mass located within the left orbit, characterized by areas of “fluffy amorphous increased density” with imaging features characteristic of osteoid matrix (Fig. 2). The epicenter of the mass was located in the globe, with extension to adjacent rectus muscles resulting in secondary exophthalmos. The tumor also tracked along the optic nerve with relative preservation of the nerve. There was no evidence of osseous involvement or invasion with complete preservation of the wall of the orbit circumferentially. The constellation of imaging findings was concerning for extraskeletal osteosarcoma involving the orbit.

Fig. 2.

Axial CT images (a), soft tissue window on the left and bone window on the right, demonstrating a large heterogeneous soft tissue mass in the left orbit (asterisk) with secondary exophthalmos. The epicenter of the mass is on the globe of the eye with secondary mass effect on the medial and lateral rectus muscles (arrows). No evidence of osseous invasion. Coronal CT (b), with bone window settings on the left and sagittal CT with soft tissue settings, demonstrating the large heterogeneous mass with osteoid matrix within the orbit with preservation of the orbital rim (arrows). The tumor exerts mass effect on the superior rectus muscle (asterisk) and tracks along the optic nerve.

During the planned operative procedure, an orbital mass extending into the extraocular muscle was identified and biopsied. Intraoperative frozen section confirmed high-grade sarcoma. Enucleation was performed.

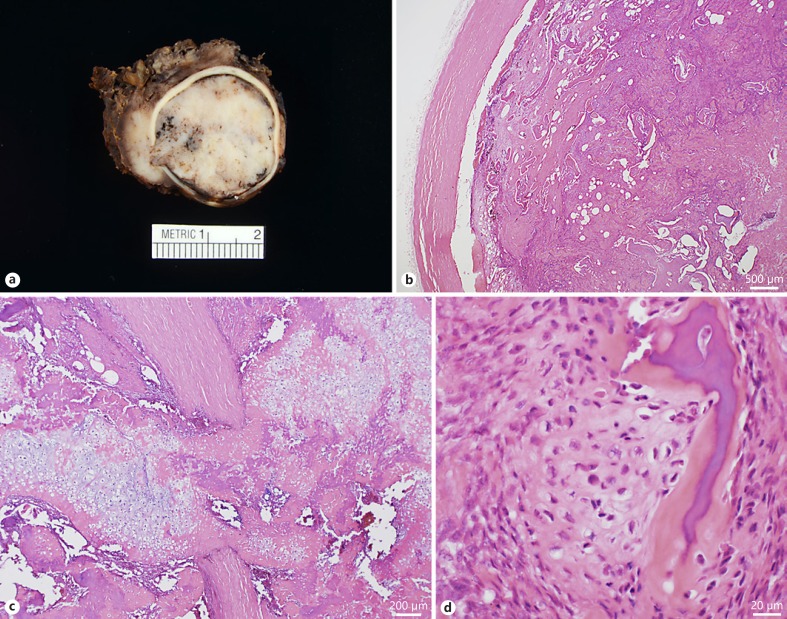

Grossly, the entire globe was filled with a 2.5-cm tan-white mass with a granular surface. The intraocular mass focally penetrated the sclera to invade periocular soft tissues, including an extraocular muscle (Fig. 3a). Microscopically, the tumor was composed of mitotically active, markedly atypical spindle and epithelioid cells with abundant lack-like osteoid production obliterating native ocular structures, including the lens and iris (Fig. 3b) and breaking through the sclera (Fig. 3c). The only recognizable residual intraocular tissue was the pars plicata of the ciliary body. Foci of metaplastic bone surrounded by malignant cells were also noted (Fig. 3d). The diagnosis of high-grade extraskeletal osteosarcoma, osteoblastic subtype, was confirmed by a pathologist with expertise in bone pathology.

Fig. 3.

Gross picture of the enucleated specimen showing the entire eye filled by a whitish, chalky, and partially calcified mass rupturing through the sclera involving adjacent soft tissues (a). Low-power microscopic section demonstrating complete replacement of the intraocular tissues (b, H&E, ×20) with rupture through the sclera invading orbital soft tissues (c, H&E, ×40). The malignant cells permeate pre-existing metaplastic bone commonly encountered in phthisis bulbi (d, H&E, ×400).

Given the diagnosis of osteosarcoma involving the left eye and surrounding orbital soft tissues, the patient underwent an orbital revision a month later; however, the tumor could not be completely excised, and the patient was referred to oncology. Positron-emission tomography confirmed that the disease was confined to the orbit, and radiation therapy in the form of 60 Gy in 33 fractions was administered. The patient expired 5 months after his initial diagnosis with tissue-confirmed pulmonary metastases.

Discussion

Osteosarcoma is a malignant matrix-producing tumor that typically arises from bone. While sarcomatoid carcinoma and soft tissue sarcomas, such as dedifferentiated liposarcoma, may harbor a heterologous osteosarcomatous component, osteosarcoma arising in soft tissue without connection to the underlying bone (extraskeletal osteosarcoma) is uncommon, accounting for only 1–2% of all soft tissue sarcomas [1, 2, 3]. Extraskeletal osteosarcomas tend to arise in older adults with most patients presenting after the fourth decade of life [2, 3]. The most common anatomic location is the thigh/buttocks region, with most tumors arising deep to the fascia [2, 4]. Approximately 5–10% occur in the setting of prior radiation exposure, and a subset of patients report a history of trauma at the tumor site [2, 4].

Only 5 cases of primary orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma are identified in the literature (Table 1). The age range is broad and, similar to non-orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma, 2 of the 5 patients had a history of radiation. In 2000, Long et al. [5] reported an 86-year-old woman with extraskeletal osteosarcoma following a 20-year history of phthisis bulbi secondary to multiple ocular procedures and uncontrolled glaucoma. While earlier descriptions of extraskeletal osteosarcoma arising in phthisical eyes in felines have been reported [6, 7, 8], Long et al.'s report is the only other example involving a phthisical human eye. Similar to our case, their patient's presentation included pain and proptosis. She was treated with surgical resection and was alive without disease 9 months after surgery [5]. Metastatic osteosarcoma to the orbit, although rare, can also occur; however, the primary osseous tumor is usually known at the time the metastasis is identified [9, 10].

Table 1.

Reported cases of orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma

| Reference | Year | Age, years/sex | Presenting symptoms | Significant history | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kauffman et al. [23] | 1963 | 11/male | Mass | Enucleation for retinoblastoma with subsequent radiation at 3 months of age | Radical maxillary resection | Died of disease 9 months after diagnosis |

| Jacob et al. [24] | 1998 | 22/male | One-year history of swelling, pain, proptosis | None | Chemotherapy | Alive without disease 2 years after diagnosis |

| Long et al. [5] | 2000 | 86/female | Pain and proptosis for several weeks | Phthisis bulbi secondary to cataract extractions and uncontrolled glaucoma | Orbital exenteration | Alive without disease 9 months after diagnosis |

| Fan et al. [25] | 2011 | 78/male | Rapidly growing mass | Long-term immunosuppression, radiation 1 year prior for canthal basal cell carcinoma | Orbital exenteration and partial maxillectomy | Alive without disease 6 months after diagnosis |

| De Maeyer et al. [26] | 2016 | 32/male | Proptosis | None | Chemotherapy, radiation | Alive without disease 3 years after diagnosis |

Phthisical eyes are known to harbor neoplasms in a small percentage of cases. The majority of these tumors are uveal melanomas [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]; however, non-melanocytic neoplasms such as choroidal lymphoma, retinoblastoma, and carcinoma of the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium have also been reported [16, 17]. In fact, this has been one of the strongest arguments raised recently against an increased practice of performing evisceration for phthisis bulbi [18, 19]. Metaplastic bone is often seen in phthisical eyes, raising the possibility of malignant transformation of a benign bone-forming process. While isolated reports of myositis ossificans with malignant transformation exist in the literature, convincing evidence is lacking [20, 21].

Although unusual, the diagnosis of osteosarcoma is typically straight-forward once these lesions are examined histologically. The presence of malignant cells with osteoid matrix production is sufficient for the diagnosis of extraskeletal osteosarcoma. While metaplastic bone is relatively common in phthisical eyes, the presence of atypia in the cellular component should warrant consideration of osteosarcoma. Careful, clinical, and radiologic correlation is essential to ensure that the tumor is not a metastasis or arising from a surrounding bony structure.

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is reported to have a poorer prognosis when compared to its skeletal counterpart. Despite improvements in chemotherapy regiments, the overall 5-year survival rate is < 50% [22]. The clinical behavior of orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma appears to mirror these findings as 2 (of 6) patients died within a year. While the other patients were reported to be alive without disease, follow-up is < 5 years in all cases.

In summary, we report the second case of extraskeletal osteosarcoma arising in phthisis bulbi. Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of this rare malignancy that may present in phthisical eyes, especially in patients reporting pain and proptosis, to facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Statement of Ethics

This case report was granted exempt status by our Institutional Review Board.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Klein MJ, Siegal GP. Osteosarcoma: anatomic and histologic variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:555–581. doi: 10.1309/UC6K-QHLD-9LV2-KENN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, Fetsch JF, Wasdhal DA, Lee BP, Pritchard DJ, Nascimento AG. A review of 40 patients with extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1995;76:2253–2259. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2253::aid-cncr2820761112>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lidang Jensen M, Schumacher B, Myhre Jensen O, Steen Nielsen O, Keller J. Extraskeletal osteosarcomas: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:588–594. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199805000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1987;60:1132–1142. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870901)60:5<1132::aid-cncr2820600536>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long JA, Lolley VR, Kelly AG. Osteogenic sarcoma and phthisis bulbi: a case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16:75–78. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubielzig RR, Everitt J, Shadduck JA, Albert DM. Clinical and morphologic features of post-traumatic ocular sarcomas in cats. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:62–65. doi: 10.1177/030098589002700111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groskopf BS, Dubielzig RR, Beaumont SL. Orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma following enucleation in a cat: a case report. Vet Ophthalmol. 2010;13:179–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2010.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woog J, Albert DM, Gonder JR, Carpenter JJ. Osteosarcoma in a phthisical feline eye. Vet Pathol. 1983;20:209–214. doi: 10.1177/030098588302000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohadjer Y, Wilson MW, Fuller CE, Haik BG. Primary pelvic telangiectatic osteosarcoma metastatic to both orbits. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:77–79. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000103002.04762.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajabi MT, Jafari H, Hosseini SS, Tabatabaie SZ, Rajabi MB, Amoli FA. Orbital metastasis: a rare manifestation of scapular bone osteosarcoma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9:517–519. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.150834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holla A, Gonsalves SR. Choroidal melanoma presenting with anterior segment involvement and phthisis bulbi. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine RA, Putterman AM, Korey MS. Recurrent orbital malignant melanoma after the evisceration of an unsuspected choroidal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:571–574. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makley TA, Jr, Teed RW. Unsuspected intraocular malignant melanomas. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;60:475–478. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080493020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarma DP, Deshotels SJ, Jr, Lunseth JH. Malignant melanoma in a blind eye. J Surg Oncol. 1983;23:169–172. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930230309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripathi A, Hiscott P, Damato BE. Malignant melanoma and massive retinal gliosis in phthisis bulbi. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:781–782. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saeed MU, Chang BY, Anand S, Chakrabarty A. Diagnostic surprise in an evisceration specimen. Orbit. 2007;26:129–131. doi: 10.1080/01676830600974902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundar JK, Krishnakumar S, Biswas J. Retinoblastoma presenting as panophthalmitis: clinicopathological study of a case. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2002;39:178–180. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20020501-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle RC, Jr, Grossniklaus HE, Syed N, Hogan RN, Lloyd WC, 3rd, Folberg R. Inadvertent evisceration of eyes containing uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:141–145. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rath S, Honavar SG, Naik MN, Gupta R, Reddy VA, Vemuganti GK. Evisceration in unsuspected intraocular tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:372–379. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarvi OH, Kvist HT, Vainio PV. Extraskeletal retroperitoneal osteosarcoma probably arising from myositis ossificans. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968;74:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1968.tb03450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konishi E, Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Tsuchihashi Y, Beabout JW, Unni KK. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma arising in myositis ossificans. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s002560000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longhi A, Bielack SS, Grimer R, Whelan J, Windhager R, Leithner A, Gronchi A, Biau D, Jutte P, Krieg AH, Klenke FM, Grignani G, Donati DM, Capanna R, Casanova J, Gerrand C, Bisogno G, Hecker-Nolting S, De Lisa M, D'Ambrosio L, Willegger M, Scoccianti G, Ferrari S. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma: a European Musculoskeletal Oncology Society study on 266 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauffman SL, Stout AP. Extraskeletal osteogenic sarcomas and chondrosarcomas in children. Cancer. 1963;16:432–439. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196304)16:4<432::aid-cncr2820160403>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob R, Abraham E, Jyothirmayi R, Nair MK. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the orbit. Sarcoma. 1998;2:121–124. doi: 10.1080/13577149878082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan JC, Lamont DL, Greenbaum AR, Ng SG. Primary orbital extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Orbit. 2011;30:297–299. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2011.602170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Maeyer VM, Kestelyn PA, Shah AD, Van Den Broecke CM, Denys HG, Decock CE. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the orbit: a clinicopathologic case report and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:687–689. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.97555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]