Abstract

Langerhans cells (LC) are epidermal resident antigen-presenting cells that share a common ontogeny with macrophages but function as dendritic cells (DC). Their development, recruitment and retention in the epidermis is orchestrated by interactions with keratinocytes through multiple mechanisms. LC and dermal DC subsets often show functional redundancy but LC are required for specific types of adaptive immune responses when antigen is concentrated in the epidermis. This review will focus on those developmental and functional properties that are unique to LC.

Langerhans cells (LC) are the only MHC class II expressing antigen-presenting cells (APC) under steady-state conditions in the epidermis, the outermost cellular layer of the skin. They were initially observed by Paul Langerhans in 1868 and thought to function as part of the peripheral nervous system but landmark studies 40 years ago placed them firmly within the hematopoietic system 1–4. Early work by Ralph Steinman and others approximately 30 year ago found that immature LC and dendritic cells (DC) efficiently acquired and processed antigen5,6. Exposure of LC and DC to activating stimuli allowed for highly efficient activation of naive T cells in mixed lymphocyte reactions. Inflammatory stimuli also greatly enhanced migration of LC out of the epidermis and into regional lymph nodes (LN). Thus, LC were considered the prototypical migratory DC envisioned by the DC-paradigm leading also to coinage of the term “LC paradigm”7. A corollary to the DC-paradigm is that presentation of self antigen by DC or LC in the absence of inflammatory stimuli deletes or silences autoreactive T cell clones thereby providing a basis for peripheral self-tolerance8. The location of LC at a barrier surface provides them with access to skin pathogens, commensal organisms, allergens, contact sensitizers and epidermal self-antigens. Thus, LC were assumed to mediate initiation of adaptive immunity against foreign antigens and tolerance to self-antigens found in the skin.

More recently, there has been considerable progress investigating skin DC. Notably, several subsets of dermal DC were identified and have been shown to be required for many of the functions originally ascribed to LC. The phenotypes (Table 1) and functions of skin APC subsets have been reviewed recently9. In addition, LC were found to be closely related to macrophages based on a shared ontogeny10,11. Thus, LC are turning out to be a rather unique cell type. This review will explore the unique aspects of murine LC biology and the contribution these cells provide to the establishment and regulation of cutaneous immune responses.

Table 1.

Mouse antigen-presenting phenotypes

| Name | LC | Dermal cDC1 | Dermal cDC2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Names | XCR1+ dDC | CD11b+ dDC | ||

| CD103+ dDC | IRF4 dDC | |||

| IRF8+ dDC | ||||

| Location | Epidermis | Dermis | Dermis | |

| Transcription Factors | ID2 | + | + | − |

| PU.1 | + | − | ||

| Runx3 | + | − | − | |

| Batf3 | − | + | − | |

| IRF4 | − | − | + | |

| IRF8 | + | + | − | |

| Surface Markers | CD8a | − | − | − |

| CD103 | − | + | − | |

| XCR1 | − | + | − | |

| Clec9A | − | + | − | |

| CD11b | + | − | + | |

| CD207 (Langerin) | + | + | − | |

| CD301b | −/+ | − | + | |

| CD172 | − | − | + | |

| CD64 | − | − | − | |

| MERTK | − | − | − | |

| CCR2 | − | − | − | |

| F4/80 | + | − | − | |

| Soluble | ||||

| Factors/Receptors | Flt3 | − | + | + |

| CSF-1R | + | − | + | |

| CSF-2R | − | + | + | |

| IL-34 | + | − | − | |

| TGF-β | + | − | − |

Development and maintenance of the epidermal LC network

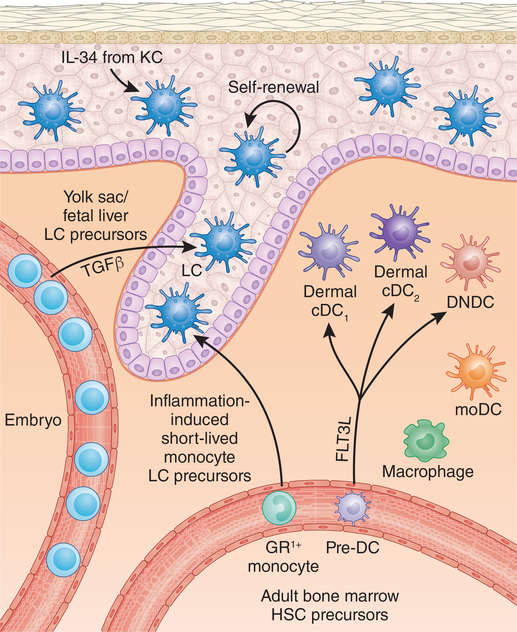

During ontogeny, primitive myeloid LC progenitors initially from the yolk-sac and later from the fetal liver seed the skin (Fig. 1) 11. On day 2 after birth, these cells undergo a 10–20-fold expansion during which they assume a dendritic morphology and begin to express the surface markers MHC class II and Langerin in a step-wise manner with ultimate establishment of the adult LC network by 3 weeks of age12,13. LC differentiation requires several transcription factors related to Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling including Runx3 and ID2 as well as engagement of the receptor CSF1R (MCSFR) by KC-derived IL-3410,14–17. Once formed, adult LC form a self-renewing, radio-resistant population within the epidermis18.

Figure 1. Antigen presenting cells in the skin.

LC are the only MHC class II antigen presenting cells in uninflamed epidermis. They arise from embryonic monocytic precursors and in the adult can be easily identified based on their epidermal location and surface markers (Table 1). The dermis is populated by two major subsets of DC that arise from dedicated pre-DC precursors in the bone-marrow. Dermal cDC1 are closely related to cDC1 in secondary lymphoid tissues. Dermal cDC1 are often referred to based on their surface marker expression and transcription factor dependence as XCR1+ dDC, CD103+ dDC or IRF8+ dDC. Dermal cDC2 are closely related to cDC2 in secondary lymphoid tissue and are often termed CD11b+ dDC or IRF4 dDC. A less well characterized DC subset termed double-negative DC (DNDC) based on the absent expression of CD103 and CD11b as well as macrophages and monocyte-derived DC (moDC) also reside in the dermis. During inflammation, monocyte-derived LC are recruited into the epidermis at the follicular isthmus and infundibulum but are excluded from the bulge region.

Notably, LC ontogeny is clearly distinct from classic DC development. DC arise from bone-marrow precursors, require the cytokine Flt3L, have a short half-life and do not self-renew. LC development more closely resembles that of other tissue macrophages, particularly microglia. Like microglia, LC arise from primitive myeloid progenitors and require tissue-derived IL-3416,19. This is further supported by the fact that macrophage populations can self-renew in peripheral tissues. Thus, it has been proposed that LC should be considered a subset of tissue macrophages akin to microglia in the brain, alveolar macrophages in the lung and Kupffer cells in the liver 20,21. While this makes sense based on ontogeny, it neglects the fact that LC, unlike tissue macrophages have the capacity to migrate into regional lymph nodes. The LC gene expression profile matches that of other migratory DC populations and they can efficiently prime naive T cells22,23. This is a critical function not shared with tissue macrophages. The dichotomy between ontogeny and function likely results from tissue programming of precursors by the epidermis as has been demonstrated with macrophages by adoptive transfer between tissues24,25,26. Thus, while LC in the skin share many features with tissue macrophages and have been speculated to have macrophage-like functions while skin-resident, they also clearly function as DC. Thus, LC are a unique, hybrid cell type that are probably best considered to be a specialized form of DC.

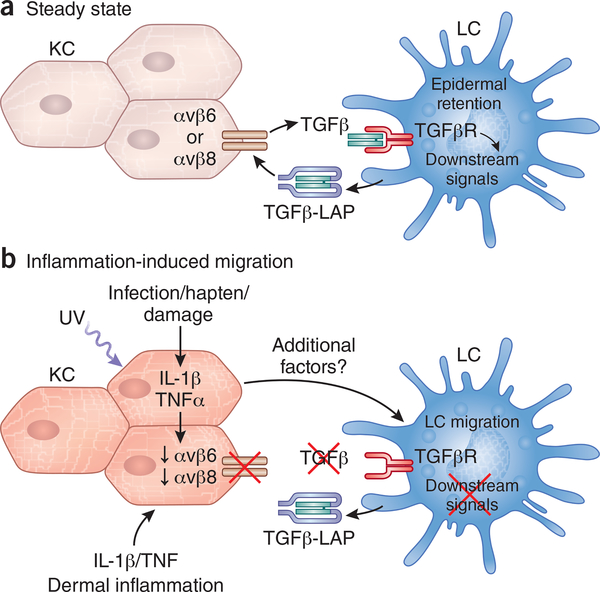

The cytokine TGF-β1 is particularly important for the development of the LC network. In vitro cultures of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) precursors yield LC in the presence of TGF-β1. Mice lacking the transcription factors ID2, Runx3, and Pu.1 as well as Axl that are all involved with TGFβ1-responses, lack or have reduced LC numbers14,15,27,28. BMP7, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is required for optimal LC development29. Finally, Tgfb2−/− mice lack LC30. Interestingly, TGF-β1 signaling is also required to maintain the LC network after it has developed. When mice in which Tgfbr1, Tgfbr2, or genes such as Lamtor2 in the TGF-β pathway are conditionally ablated from LC they lose the capacity to remain in the epidermis and spontaneously migrate into regional lymph nodes31–33. Similarly, ablation of Tgfb1 from differentiated LC results in spontaneous homeostatic LC migration32,34. Thus, despite many sources of TGF-β1 in the epidermis (e.g. keratinocytes, γδ T cells and LC), LC depend on autocrine and/or paracrine TGF-β1 for epidermal residence. TGF-β1 signaling is also sufficient to prevent homeostatic LC migration as mice in which LC express a mutated, constitutively active TGF-βRI fail to migrate to regional lymph under steady-state conditions (Fig. 2) 35. TGF-β1 is secreted as an inactive, latent form associated with LAP and in the epidermis requires activation by the integrins avβ6 or avβ8 that are expressed by non-overlapping subsets of keratinocytes (avβ6 in the interfollicular regions and avβ8 near the hair follicles) 35,36. Thus, transactivation of LC-derived TGF-β1 by integrins expressed by keratinocytes is required to maintain the epidermal residence of LC under non-inflammatory conditions. TGF-β1 signaling is required for expression of Axl that has anti-inflammatory effects and may act on LC as well as KC to inhibit migration 28. From this, the inference is reasonably made that keratinocyte expression of avβ6 or avβ8 likely in conjunction with additional signals may be a required event for homeostatic LC igration.

Figure 2. Keratinocytes and TGF-β control LC migration.

Under steady-state conditions, integrins avβ6 and avβ8 transactivate LC-derived TGF-β-LAP. a) Tonic TGF-β signaling in LC as well as LC-KC structural interactions are required for their epidermal retention. b) Migratory signals such as UV light reduce KC expression of avβ6 and avβ8 reducing the availability of active TGF-β. The absence of active TGF-β likely in conjunction with still unknown factors results in LC migration. Inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF from KC and dermal infiltrates also promote LC migration but likely act indirectly on KC.

LC self-renew and remain of host origin in murine bone marrow transplantation models18,37,38. LCs can repair DNA damage through the action of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, CDKN1A, which permits cell cycle arrest, providing protection against ionizing radiation39. However, strong inflammatory stimuli such as UV light can deplete LC10. In this context, CCR2-dependent GR1hi monocytes are recruited into the epidermis to replace LC that have migrated (Fig. 1) 10. Recruitment of monocyte precursors into the epidermis occurs at the hair follicle and requires the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR640. The ligand for CCR2, CCL2, is expressed at the follicular isthmus and the ligand for CCR6, CCL20 is expressed at the follicular infundibulum. LC are excluded from the immune-privileged bulge region containing keratinocyte stem cells by CCL8 and CCR8. Interestingly, LC derived from GR1hi monocytes arise independently of TGF-β and are short lived in the epidermis. They are replaced by a second wave of steady-state-derived long-term LC41. The biological significance of these transient monocyte-derived LC remains unclear through there is evidence to suggest they participate in inflammatory cytokine circuits in psoriatic skin42,43.

Activation-induced LC migration

Exposure to UV light and haptens are the best studied inflammatory stimuli that lead to LC activation and migration. Activated LC reduce expression of E-cadherin that forms a structural tether with E-cadherin-expressing keratinocytes thereby allowing egress from the epidermis44. Migration out of the epidermis is facilitated by CXCR4 and the adhesion molecular EpCAM45–47. Activated LC begin to express CCR7 and once in the dermis follow a CCL19 and CCL21 chemokine gradient through the dermal lymphatics and into the paracortex of the skin-draining LN48.

LC migration is triggered by the coordinated action of IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF since administration of blocking antibodies to these inflammatory cytokines and Casp1−/−, Il1b− /− and Tnfr2−/− mice show decreased hapten-induced migration49–53. It remains unclear, however, whether these cytokines act on LC directly or indirectly via KC (Fig. 2). LC migration in response to hapten and Candida albicans infection is unaffected in mice with a selective LC ablation of MyD88 that renders them insensitive to IL-1β and IL-18 as well as Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) ligands found in the C. albicans cell wall54. In contrast, mice with a KC-specific ablation of MyD88 have reduced levels of LC migration in response to protein immunization55. In addition, UV exposure reduces the capacity of keratinocytes to provide active TGF-β to LC and constitutive TGF-β signaling in LC inhibits both UV-induced expression of CCR7 and LC migration35. Thus, keratinocytes play an important role in facilitating LC migration56 and, in at least some contexts, regulated TGF-β transactivation by keratinocytes may act as a trigger for LC migration.

Langerhans cells and priming adaptive T cell responses

Despite intense focus by many laboratories, the precise function of LC remains controversial largely due to the use of varying techniques. Early work focused on LC in culture. The identification, however, that LC selectively express Langerin, a c-type lectin receptor, was a major breakthrough57. Using Langerin as a LC marker greatly facilitated analysis of LC ex vivo and allowed for the engineering of 3 independently derived mouse lines that efficiently ablated LC (Table 2). The primate diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) was introduced into the endogenous Langerin locus to create two lines of murine Langerin-DTR (muLangerin-DTR) mice58,59. Human genomic BAC DNA containing the Langerin locus that had been modified to express active Diphtheria toxin or DTR was used to create human Langerin-DTA (huLangerin-DTA) and huLangerin-DTR transgenic mice60,61. It was later discovered that dermal cDC1 (also known as CD103+ dDC) and cDC1 (also known as LN and spleen resident CD8+ DC) in on the C57BL/6 genetic backgrounds also express Langerin. This clearly complicated interpretation of the early work utilizing muLangerin-DTR mice and analyzing LC based on Langerin expression. HuLangerin-DTA and huLangerin-DTR mice selectively target LC since transgene expression recapitulates the human pattern of Langerin expression in LC but not cDC1.

Table 2.

LC depleter mouse lines

| Model | Specificity | Caveats |

|---|---|---|

| muLangerin-DTR DT Day -1 | LC Dermal cDC1 and cDC1 in C57BL/6 mice |

LC and dermal cDC1 ablated |

| muLangerin-DTR DT Day -7/13 | LC Dermal cDC1 have largely repopulated |

Dermal cDC1 numbers reduced |

| WT→muLangerin-DTR Bone marrow chimera |

LC | Reconstitution may not be complete. DETC may not reconstitute |

| huLangerin-DTA | LC | Constitutive absence of LC and possible compensatory effects Potential additional genes on BAC transgenic |

| huLangerin-DTR | LC | Potential additional genes on BAC transgenic |

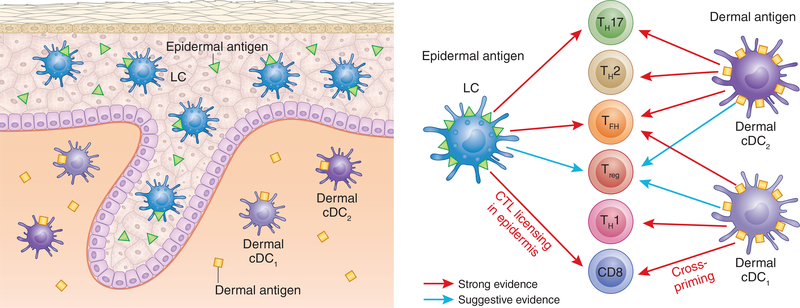

These early technical problems have been largely overcome. The phenotype of LC is now well characterized and they can be easily and reliably isolated from lymph node using several markers including CD11c+, MHC class II+, Langerin+ (CD207+), CD11b+, CD103− (Table 1). To selectively ablate LC in muLangerin-DTR mice, DT can be administered 1–2 weeks prior to experimentation (Table 2) 62. Since LC repopulate the epidermis after ablation more slowly than dermal cDC1 under steady-state conditions, there is a window after DT administration where LC are absent but dermal cDC1 have largely recovered. Using muLangerin-DTR mice as recipients in bone marrow chimera experiments is also commonly employed. Since LC are radio-resistant and self-renew, they remain of host origin in chimeras18. Thus, administering DT to Wild-type → muLangerin-DTR chimeras targets LC and not dermal cDC1 that have repopulated from donor origin. Although these approaches all have their caveats, there is now a large body of literature that accurately assays LC requirement in vivo across many contexts (Fig. 3) that will be explored below.

Figure 3. Murine skin DC subsets drive distinct T cell phenotypes.

LC, dermal cDC1, and dermal cDC2 promote distinct but overlapping T cell phenotypes. In most contexts, the same antigen is present in both the epidermis and dermis resulting in a redundancy between LC and dermal DC subsets. A requirement for LC is observed primarily when antigens or adjuvants are confined to the epidermis. Strong evidence is shown by red arrows and suggestive evidence is shown in blue.

LC in cross presentation

Presentation of exogenous antigen by DC requires specialized processing and cross-presentation, a function critical for cytotoxic T cell responses against viruses, intracellular pathogens and tumors. Targeting antigen to the correct DC subsets for cross-presentation is an important goal for effective vaccine design. In general, mouse and human dermal cDC1 have a superior ability compared with LC to present particulate or necrotic cell-derived antigens for cross-priming to CD8+ T cells, particularly in the context of TLR3 co-stimulation63–65. In the context of cutaneous infections, Batf3−/− mice deficient in cDC1 but not mice lacking LC are unable to mount CD8+ T cell response against epicutaneous infection with C. albicans or herpes simplex virus, priming of commensal specific IL-17 secreting CD8+ T cells and rejection of syngeneic tumors66–69. Moreover, dermal cDC1 more efficiently cross prime keratinocyte derived self-antigens to CD8+ T cells suggesting a role in cross-tolerance67,70.

Despite being less efficient than cDC1, there is evidence that LC are capable of cross presenting antigen to CD8 T cells in certain contexts. In vitro, antigen-pulsed LC can cross present antigen71. LC deficient mice develop reduced CTL mediated immunity following cutaneous immunization with antigen conjugated nanoparticles72. LC targeted in vivo with foreign antigen using an anti-Langerin antibody conjugated to antigen in the presence of certain adjuvants resulted in CD8 proliferation but functional tolerance (e.g. cross-tolerance), not cross priming73. Finally, like most DC, LC can present endogenous antigen to CD8 T cells resulting in direct-tolerance or direct-priming in the presence of an adjuvant (Stoecklinger in press). In the context of graft vs. host disease where LC are a source of alloantigens, LC within the skin are required to license pathogenic CD8 effectors74[ Santos e Sousa NI 2017 under review—ZOLTAN what is the status??].

LC and TH17 cell differentiation

TH17 cells protect against extracellular fungal and bacterial pathogens and can be pathogenic in autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis. LC are required for the development of TH17 responses in response to C. albicans epicutaneous skin infection and provide protection to subsequent cutaneous but not systemic C. albicans infections66,75,76. In this context, LC engaging with Dectin-1 ligands expressed by C. albicans yeast were a non-redundant source of IL-6, a key cytokine required for TH17 differentiation. The absence of LC had no effect on TH1 differentiation in this model. Mice with a keratinocyte specific ablation of the protease ADAM17 develop spontaneous cutaneous dysbiosis with overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus. In this model, LCs were required for the generation of IL-17-producing CD4+ and γδ T cells in the skin77. The capacity to promote TH17 is not unique to LC as cDC2 are required for TH17 generation against bacterial and fungal pathogens in other tissues78,79. TH17 differentiation in response to epicutaneous C. albicans infection depends on LC and not dermal cDC2 because the ligand for Dectin-1 is available primarily on C. albicans yeast forms found in the epidermis and not hyphal forms found in the dermis. The same is likely true in ADAM17-deficient mice where dysbiotic S. aureus remain superficial on the skin. Thus, LC are required for TH17 differentiation particularly when the antigen is concentrated in the epidermis.

LC and TFH and TH2 cell differentiation

The development of humoral immunity to cutaneous antigen involves the induction of CD4+ T follicular helper (TFH) cells that promote plasma cell and germinal center (GC) development. LC can acquire epicutaneously applied antigen and were required for the production of protective IgG1 in a model of Staphylococcus scalded skin syndrome80,81. LC-deficient mice have decreased GC and TFH cell responses after intradermal immunization and infection with Leishmania major82,83. Foreign antigen targeted selectively to LC expanded TFH cells and promoted GC formation resulting in antigen-specific IgG1 thus indicating that antigen presentation by LC is sufficient to promote a humoral response84. The ability to promote humoral responses, however, is not unique to LC. Foreign but not self-antigen targeted to cDC1 even in the absence of adjuvant induced TFH cell expansion, GC formation and protective antibody responses85,86. In addition, TFH cells and GC responses after an intradermal nanoparticle immunization required DC migration but were only partially abrogated by the absence of LC while GC formation in response to hapten that penetrates deep into skin was independent of LC83. Thus, it appears that LC like other subsets of DC have the capacity to promote humoral responses.

LC may have a special function for the development of IgE. Epicutaneous immunization with OVA results in antigen-specific IgE that is reduced in mice lacking LC and mice with LC-specific ablation of the receptor for the cytokine TSLP 87. In addition, LC-deficient mice have reduced steady-state levels of serum IgE. In this model, LC are not required for T cell proliferation but are required for optimal IL-4 expression in skin draining LN suggesting a possible role in TH2 differentiation. TH2 differentiation to epicutaneous house dust mice, however, is clearly reduced in Irf4fl/flItgax (CD11c)-Cre mice indicating a requirement for dermal cDC2 but not LC88. Antigen-specific IgE and IgG1 are reduced after dermal injection of antigen in Irf4fl/flItgax Itgax-Cre mice but this was not observed after dermal infection with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasilliensis in MGL2-DTR mice that target cDC2 as well as macrophage populations89,90. TH2 differentiation in the intradermal papain model was not affected by the absence of LC and LC ablation of STAT5 that is required for TSLP signaling did not reduce TH2 differentiation in response to epicutaneous challenge with the hapten FITC90,91. Thus, LC can promote IgE production in response to epicutaneous protein immunizations but their capacity to promote TH2 differentiation appears to be limited.

LC and tolerance induction

The concept that antigen presentation by immature DC promotes anergic or immunosuppressive T cells to support peripheral tolerance has been well established by classic antigen targeting experiments92–94. This is likely true for LC since resting human LC activate and induce proliferation of skin-resident regulatory T (Treg) cells in vitro whereas activated LC preferentially induced proliferation of effector memory T cells95. These experiments analyzed skin-resident memory cells and it is less clear whether LC have a special capacity to induce tolerance. Targeting antigen to LC in vivo promotes Treg cell proliferation but this appears to be restricted to self and not foreign antigen84,96. In the specific context of L. major infection, LC suppress anti-Leishmania responses possibly through Treg cell expansion97. In mouse models of allergic contact dermatitis, pretreatment with a precise dose of the innocuous hapten DNTB can tolerize to subsequent sensitization with DNFB, a strong sensitizer, through a mechanism that require LC for CD8 T cell tolerance and activation of Treg cell 98. Thus, there are specific situations where LC appear to promote tolerance that may be related to antigen restriction to the epidermis. The promotion of tolerance, however, is not a special attribute of LC since all migratory DC share a similar immune-suppressive gene expression profile and subsets of dermal DC also promote tolerance99–102. Moreover, mice with constitutive ablation of LC or other individual DC subsets have not been reported to develop autoimmunity. Thus, individual skin DC subsets are likely sufficient but redundant for peripheral tolerance in most contexts.

LC and contact hypersensitivity

Contact hypersensitivity (CHS) is a mouse model for human allergic contact dermatitis103. In general, small molecule sensitizing haptens that penetrate the skin are used to immunize mice and the effector response is measured after application of the same hapten at a distant site. Selective ablation of LC in muLangerin-DTR mice using either the delayed immunization or bone marrow chimera techniques (Table 2 and discussed above) did not affect CHS responses62,104. A requirement for LC, however, was observed at low doses of hapten that may concentrate antigen in the epidermis105. Urushiol, the active sensitizer in poison ivy, is presented to T cells on CD1a – an antigen-presenting molecule that is strongly expressed by human and not mouse LC106. Transgenic mice expressing human CD1a on LC have greatly increased CHS responses to urushiol 107. Thus, human LC are likely the key antigen presenting cell in allergic contact dermatitis to antigens presented through CD1a but in mice, their role is limited to contexts in which antigen is primarily epidermal.

In contrast to data using muLangerin-DTR models of LC ablation, CHS to several haptens at a range of doses is reliably increased in huLangerin-DTA mice that have a constitutive and selective absence of LC60,108. Acute ablation of LC in huLangerin-DTR mice prior to sensitization also increases CHS responses, though the effect is less pronounced and consistent than with huLangerin-DTA mice61. Cells isolated from lymph nodes of huLangerin-DTA mice can adoptively transfer exaggerated CHS responses. Mice with a constitutive LC-specific ablation of MHC class II or IL-10 but not MyD88 also have increased CHS responses54,108. Notably, delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses to C. albicans is also increased in huLangerin-DTA mice66. A similar exaggerated response is observed after intradermal injection of C. albicans in naive huLangerin-DTA mice109. This occurs only in the context of constitutive ablation or long-term depletion (DHK, unpublished observation) of LC and can be adoptively transferred to wild type mice by liver resident type I innate lymphoid cells (ILC1). These data raise the possibility that LC may indirectly suppress cutaneous immune responsiveness or the long-term absence of LC may promote an unidentified compensatory inflammatory response.

Concluding thoughts and future perspective

The past several years has seen significant progress in the understanding of murine LC biology. The recognition that LC are only one of several antigen-presenting-cells in the skin and the development of tools to accurately identify and target LC have allowed for a more detailed and nuanced study of LC. It is now appreciated that LC are a unique cell type that have a close ontogenetic relationship with macrophages and a close functional relationship with DC. To date, most of the functional analysis of LC has focused on their capacity to drive antigen specific T cell responses. LC are clearly involved in TH17 and TFH cell differentiation. There is also support for their involvement in Treg cell, CD8 T cell and perhaps TH2 responses. They appear to have little involvement in TH1 immunity. LC share many of these functions with other DC subsets and are non-redundant primarily in contexts in which antigen is confined or concentrated to the epidermis. This fits well with the concept that an individual DC subset has the potential to promote several but not all T helper phenotypes and that the ultimate T cell response is dictated by a combination of antigen location, DC subset presenting antigen and the microbial-associated molecular pattern and/or cytokine environment. Despite progress, there are several aspects of LC biology that remains poorly defined. The relationship of LC with immune effectors within the epidermis, the interaction of LC with cells of the innate immune system including KC, the effect of CD1a presentation of lipid molecules by LC, and whether LC share a functional along with an ontogenetic relationship with macrophages all remain to be fully explored. These represent major frontiers for future exploration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to apologize to all authors whose work was not cited or discussed in depth because of the length limitation. This work has been supported by grants R01AR060744, R01AR067187, and R01AR071720 awarded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

References

- 1.Rowden G, Lewis MG & Sullivan AK Ia antigen expression on human epidermal Langerhans cells. 268, 247–248 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klareskog L, Tjernlund U, Forsum U & Peterson PA Epidermal Langerhans cells express Ia antigens. 268, 248–250 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stingl G et al. Epidermal Langerhans cells bear Fc and C3 receptors. 268, 245–246 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silberberg-Sinakin I, Thorbecke GJ, Baer RL, Rosenthal SA & Berezowsky V Antigen-bearing langerhans cells in skin, dermal lymphatics and in lymph nodes. Cell. Immunol 25, 137–151 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuler G & Steinman RM Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med 161, 526–546 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu. Rev. Immunol 9, 271–296 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson NS & Villadangos JA Lymphoid organ dendritic cells: beyond the Langerhans cells paradigm. Immunol Cell Biol 82, 91–98 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinman RM & Nussenzweig MC Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. 99, 351–358 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashem SW, Haniffa M & Kaplan DH Antigen-Presenting Cells in the Skin. Annu. Rev. Immunol 35, annurev–immunol–051116–052215 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginhoux F et al. Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat Immunol 7, 265–273 (2006).The authors identified that LC repopulation of the epidermis after inflammation requires Gr-1hi monocytes and the CSF-1 receptor. This implicated monocyte rather than preDC as LC precursors.

- 11.Hoeffel G et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J Exp Med 209, 1167–1181 (2012).LC that develop during ontogeny arise from primarily form embryonic fetal liver monocytes. This confirmed that LC ontogeny is distinct from DC.

- 12.Chorro L et al. Langerhans cell (LC) proliferation mediates neonatal development, homeostasis, and inflammation-associated expansion of the epidermal LC network. J Exp Med 206, 3089–3100 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripp CH et al. Ontogeny of Langerin/CD207 expression in the epidermis of mice. J Invest Dermatol 122, 670–672 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fainaru O et al. Runx3 regulates mouse TGF-beta-mediated dendritic cell function and its absence results in airway inflammation. EMBO J 23, 969–979 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hacker C et al. Transcriptional profiling identifies Id2 function in dendritic cell development. Nat Immunol 4, 380–386 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greter M et al. Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity 37, 1050–1060 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y et al. IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat Immunol 13, 753–760 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merad M et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol 3, 1135–1141 (2002).In this landmark paper, LC were shown to self-renew in the skin and remain of host origin in bone-marrow chimeras. This introduced a key tool to interrogate LC and was the first indication that LC had an ontogeny distinct from other DC subsets.

- 19.Ginhoux F et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science (New York, N.Y.) 330, 841–845 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilliams M et al. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat Rev Immunol 14, 571–578 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satpathy AT, Wu X, Albring JC & Murphy KM Re(de)fining the dendritic cell lineage. Nat Immunol 13, 1145–1154 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller JC et al. Deciphering the transcriptional network of the dendritic cell lineage. Nat Immunol 13, 888–899 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpentier S et al. Comparative genomics analysis of mononuclear phagocyte subsets confirms homology between lymphoid tissue-resident and dermal XCR1(+) DCs in mouse and human and distinguishes them from Langerhans cells. J. Immunol. Methods 432, 35–49 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosselin D et al. Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell 159, 1327–1340 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavin Y et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell 159, 1312–1326 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guilliams M & Scott CL Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages? Nat Rev Immunol 17, 451–460 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chopin M et al. Langerhans cells are generated by two distinct PU.1-dependent transcriptional networks. Journal of Experimental Medicine 210, 2967–2980 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer T et al. Identification of Axl as a downstream effector of TGF-β1 during Langerhans cell differentiation and epidermal homeostasis. J Exp Med 209, 2033–2047 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasmin N et al. Identification of bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) as an instructive factor for human epidermal Langerhans cell differentiation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 210, 2597–2610 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Farr AG & Udey MC A role for endogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor beta 1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 184, 2417–2422 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kel JM, Girard-Madoux MJH, Reizis B & Clausen BE TGF-beta is required to maintain the pool of immature Langerhans cells in the epidermis. J Immunol 185, 3248–3255 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bobr A et al. Autocrine/paracrine TGF-β1 inhibits Langerhans cell migration. 109, 10492–10497 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparber F et al. The late endosomal adaptor molecule p14 (LAMTOR2) regulates TGFβ1-mediated homeostasis of Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol 135, 119–129 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan DH et al. Autocrine/paracrine TGFbeta1 is required for the development of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med 204, 2545–2552 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammed J et al. Stromal cells control the epithelial residence of DCs and memory T cells by regulated activation of TGF-β. Nat Immunol (2016). doi: 10.1038/ni.3396The transactivation of inactive TGF-β-LAP by RGD-binding integrins expressed by spatially distinct keratinocytes is required to prevent spontaneous LC migration. This indicates that keratinocytes control LC migration in some contexts.

- 36.Yang Z et al. Absence of integrin-mediated TGFbeta1 activation in vivo recapitulates the phenotype of TGFbeta1-null mice. J Cell Biol 176, 787–793 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz SI, Tamaki K & Sachs DH Epidermal Langerhans cells are derived from cells originating in bone marrow. 282, 324–326 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghigo C et al. Multicolor fate mapping of Langerhans cell homeostasis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 210, 1657–1664 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price JG et al. CDKN1A regulates Langerhans cell survival and promotes Treg cell generation upon exposure to ionizing irradiation. Nat Immunol 16, 1060–1068 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagao K et al. Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nat Immunol 13, 744–752 (2012).LC precursors are recruited into the epidermis during inflammation by CCR2-CCL2 and CCR6-CCL20. LC precursors enter the epidermis at the follicular isthmus and infundibulum and are actively excluded from the bulge by CCR8-CCL8.

- 41.Seré K et al. Two Distinct Types of Langerhans Cells Populate the Skin during Steady State and Inflammation. Immunity 37, 905–916 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martini E et al. Dynamic Changes in Resident and Infiltrating Epidermal Dendritic Cells in Active and Resolved Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 137, 865–873 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh TP et al. Monocyte-derived inflammatory Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells mediate psoriasis-like inflammation. Nat Commun 7, 13581 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang A, Amagai M, Granger LG, Stanley JR & Udey MC Adhesion of epidermal Langerhans cells to keratinocytes mediated by E-cadherin. 361, 82–85 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouwehand K et al. CXCL12 is essential for migration of activated Langerhans cells from epidermis to dermis. Eur J Immunol 38, 3050–3059 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villablanca EJ & Mora JR A two-step model for Langerhans cell migration to skin-draining LN. Eur J Immunol 38, 2975–2980 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaiser MR et al. Cancer-associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM; CD326) enables epidermal Langerhans cell motility and migration in vivo. 109, E889–97 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan S-Y, Roediger B & Weninger W The role of chemokines in cutaneous immunosurveillance. Immunol Cell Biol 93, 337–346 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffiths CEM, Dearman RJ, Cumberbatch M & Kimber I Cytokines and Langerhans cell mobilisation in mouse and man. Cytokine 32, 67–70 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antonopoulos C et al. Functional caspase-1 is required for Langerhans cell migration and optimal contact sensitization in mice. The Journal of Immunology 166, 3672–3677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang B et al. Tumour necrosis factor receptor II (p75) signalling is required for the migration of Langerhans’ cells. Immunology 88, 284–288 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shornick LP, Bisarya AK & Chaplin DD IL-1beta is essential for langerhans cell activation and antigen delivery to the lymph nodes during contact sensitization: evidence for a dermal source of IL-1beta. Cell. Immunol 211, 105–112 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eaton LH, Roberts RA, Kimber I, Dearman RJ & Metryka A Skin sensitization induced Langerhans’ cell mobilization: variable requirements for tumour necrosis factor-α. 144, 139–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haley K et al. Langerhans cells require MyD88-dependent signals for Candida albicans response but not for contact hypersensitivity or migration. J Immunol 188, 4334–4339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Didovic S, Opitz FV, Holzmann B, Förster I & Weighardt H Requirement of MyD88 signaling in keratinocytes for Langerhans cell migration and initiation of atopic dermatitis-like symptoms in mice. Eur J Immunol 46, 981–992 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clausen BE & Stoitzner P Functional Specialization of Skin Dendritic Cell Subsets in Regulating T Cell Responses. 6, 417 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valladeau J et al. Langerin, a Novel C-Type Lectin Specific to Langerhans Cells, Is an Endocytic Receptor that Induces the Formation of Birbeck Granules. Immunity 12, 71–81 (2000).The identification of Langerin as an LC-specific marker opened the field of LC research by facilitating accurate identification of LC in lymph-node and allowing for the development of genetic mouse models to ablate LC.

- 58.Bennett CL et al. Inducible ablation of mouse Langerhans cells diminishes but fails to abrogate contact hypersensitivity. J Cell Biol 169, 569–576 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kissenpfennig A et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity 22, 643–654 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan DH, Jenison MC, Saeland S, Shlomchik WD & Shlomchik MJ Epidermal langerhans cell-deficient mice develop enhanced contact hypersensitivity. Immunity 23, 611–620 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bobr A et al. Acute ablation of Langerhans cells enhances skin immune responses. The Journal of Immunology 185, 4724–4728 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bursch LS et al. Identification of a novel population of Langerin+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 204, 3147–3156 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haniffa M et al. Human tissues contain CD141hi cross-presenting dendritic cells with functional homology to mouse CD103+ nonlymphoid dendritic cells. Immunity 37, 60–73 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jongbloed SL et al. Human CD141 +(BDCA-3) +dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. Journal of Experimental Medicine 207, 1247–1260 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J & Mortha A The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31, 563–604 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Igyarto BZ et al. Skin-resident murine dendritic cell subsets promote distinct and opposing antigen-specific T helper cell responses. Immunity 35, 260–272 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bedoui S et al. Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 10, 488–495 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Naik S et al. Commensal-dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. 520, 104–108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hildner K et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science 322, 1097–1100 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henri S et al. CD207+ CD103+ dermal dendritic cells cross-present keratinocyte-derived antigens irrespective of the presence of Langerhans cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 207, 189–206 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stoitzner P et al. Langerhans cells cross-present antigen derived from skin. 103, 7783–7788 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zaric M et al. Dissolving Microneedle Delivery of Nanoparticle-Encapsulated Antigen Elicits Efficient Cross-Priming and Th1 Immune Responses by Murine Langerhans Cells. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 135, 425–434 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flacher V et al. Murine Langerin+ dermal dendritic cells prime CD8+ T cells while Langerhans cells induce cross-tolerance. EMBO Mol Med 6, 1191–1204 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bennett CL et al. Langerhans cells regulate cutaneous injury by licensing CD8 effector cells recruited to the skin. Blood 117, 7063–7069 (2011).In a model of graft vs. host disease where LC express alloantigen, they are required to license infiltrating epidermal CD8 T cells to secrete IFN-γ and other effector molecules. This work demonstrates an important LC-T cell interaction in the epidermis.

- 75.Kashem SW et al. Candida albicans Morphology and Dendritic Cell Subsets Determine T Helper Cell Differentiation. Immunity 42, 356–366 (2015).TH17 responses to epicutaneous C. albicans skin infection requires LC. Dermal DC cannot promote TH17 due to the restriction of Dectin-1 ligands to yeast forms that do not penetrate into the dermis. This supports a model in which LC are required for TH17 responses to antigen concentrated in the epidermis.

- 76.Mathers AR et al. Differential capability of human cutaneous dendritic cell subsets to initiate Th17 responses. The Journal of Immunology 182, 921–933 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kobayashi T et al. Dysbiosis and Staphylococcus aureus Colonization Drives Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunity 42, 756–766 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linehan JL et al. Generation of Th17 cells in response to intranasal infection requires TGF-β1 from dendritic cells and IL-6 from CD301b+ dendritic cells. 112, 12782–12787 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schlitzer A et al. IRF4 transcription factor-dependent CD11b+ dendritic cells in human and mouse control mucosal IL-17 cytokine responses. Immunity 38, 970–983 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kubo A, Nagao K, Yokouchi M, Sasaki H & Amagai M External antigen uptake by Langerhans cells with reorganization of epidermal tight junction barriers. J Exp Med 206, 2937–2946 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ouchi T et al. Langerhans cell antigen capture through tight junctions confers preemptive immunity in experimental staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208, 2607–2613 (2011).LC acquire epicutaneously applied protein antigen and are required for the development of protective antibody responses in a model of Staphylococcus scalded skin syndrome. This work established that LC are required for humoral responses to superficial antigen.

- 82.Levin C et al. Critical role for skin-derived migratory DCs and Langerhans cells in TFH and GC responses after intradermal immunization. J Invest Dermatol (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zimara N et al. Langerhans cells promote early germinal center formation in response to Leishmania-derived cutaneous antigens. Eur J Immunol 44, 2955–2967 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yao C et al. Skin dendritic cells induce follicular helper T cells and protective humoral immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 0, 1387–1397.e7 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lahoud MH et al. Targeting antigen to mouse dendritic cells via Clec9A induces potent CD4 T cell responses biased toward a follicular helper phenotype. J Immunol 187, 842–850 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Park HY et al. Evolution of B Cell Responses to Clec9A-Targeted Antigen. J Immunol 191, 4919–4925 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakajima S et al. Langerhans cells are critical in epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen via thymic stromal lymphopoietin receptor signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129, 1048–1055.e6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deckers J et al. Epicutaneous sensitization to house dust mite allergen requires interferon regulatory factor 4-dependent dermal dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gao Y et al. Control of T Helper 2 Responses by Transcription Factor IRF4-Dependent Dendritic Cells. Immunity 39, 722–732 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kumamoto Y et al. CD301b⁺ dermal dendritic cells drive T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity. Immunity 39, 733–743 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bell BD et al. The transcription factor STAT5 is critical in dendritic cells for the development of TH2 but not TH1 responses. Nat Immunol 14, 364–371 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hawiger D et al. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med 194, 769–779 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bonifaz L et al. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med 196, 1627–1638 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Joffre OP, Sancho D, Zelenay S, Keller AM & Reis E Sousa C Efficient and versatile manipulation of the peripheral CD4+ T-cell compartment by antigen targeting to DNGR-1/CLEC9A. Eur J Immunol 40, 1255–1265 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seneschal J, Clark RA, Gehad A, Baecher-Allan CM & Kupper TS Human epidermal Langerhans cells maintain immune homeostasis in skin by activating skin resident regulatory T cells. Immunity 36, 873–884 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Idoyaga J et al. Specialized role of migratory dendritic cells in peripheral tolerance induction. J Clin Invest 123, 844–854 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kautz-Neu K et al. Langerhans cells are negative regulators of the anti-Leishmania response. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208, 885–891 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gomez de Agüero M et al. Langerhans cells protect from allergic contact dermatitis in mice by tolerizing CD8+ T cells and activating Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 122, 1700–1711 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Anandasabapathy N et al. Flt3L controls the development of radiosensitive dendritic cells in the meninges and choroid plexus of the steady-state mouse brain. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208, 1695–1705 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guilliams M et al. Skin-draining lymph nodes contain dermis-derived CD103(−) dendritic cells that constitutively produce retinoic acid and induce Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Blood 115, 1958–1968 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li D et al. Targeting self- and foreign antigens to dendritic cells via DC-ASGPR generates IL-10-producing suppressive CD4+ T cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine 209, 109–121 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nirschl CJ et al. IFNγ-Dependent Tissue-Immune Homeostasis Is Co-opted in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 170, 127–141.e15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaplan DH, Igyarto BZ & Gaspari AA Early immune events in the induction of allergic contact dermatitis. Nat Rev Immunol 12, 114–124 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Honda T et al. Compensatory role of Langerhans cells and langerin-positive dermal dendritic cells in the sensitization phase of murine contact hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125, 1154–1156.e2 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Noordegraaf M, Flacher V, Stoitzner P & Clausen BE Functional redundancy of Langerhans cells and Langerin+ dermal dendritic cells in contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol 130, 2752–2759 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim JH et al. CD1a on Langerhans cells controls inflammatory skin disease. Nat Immunol 17, 1159–1166 (2016).CD1a expressed by human but not mouse LC is required for allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to urushiol, the hapten in poison ivy, and psoriasis. This demonstrated that LC are required for ACD to CD1a-binding antigen and possibly self-lipids in autoimmunity.

- 107.Kobayashi C et al. GM-CSF-independent CD1a expression in epidermal Langerhans cells: evidence from human CD1A genome-transgenic mice. J Invest Dermatol 132, 241–244 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Igyarto BZ et al. Langerhans cells suppress contact hypersensitivity responses via cognate CD4 interaction and langerhans cell-derived IL-10. J Immunol 183, 5085–5093 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Scholz F, Naik S, Sutterwala FS & Kaplan DH Langerhans Cells Suppress CD49a+ NK Cell-Mediated Skin Inflammation. The Journal of Immunology 195, 2335–2342 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]