Abstract

Importance

Lumbar puncture (LP) failure rates vary and can be as high as 65%. Ultrasound guidance could increase the success of performing LP.

Objective

To summarise the evidence on the use of ultrasound guidance versus palpation method for LP.

Data sources

We searched computerised databases and published indexes, registries and references identified from bibliographies of pertinent articles without any language restrictions to find studies that compared ultrasound guidance to palpation method for performing an LP.

Study selection

Studies were included if they were randomised or quasirandomised trials in neonates and infants that compared ultrasound guidance with palpation method for performing an LP.

Data extraction and synthesis

Standardised data collection tool was used for data extraction, and two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the studies

Main outcome(s) and measure(s)

The primary outcome was the risk of LP failure, while the risk of traumatic tap, needle redirections/reinsertions and procedure durations were secondary outcomes

Results

Data from four studies and 308 participants is included in the analysis. Ultrasound imaging reduced the risk of LP failure, risk ratio of 0.58 (95% CI 0.15 to 2.28), but it was not statistically significant (p=0.44). Ultrasound imaging significantly reduced the risk of a traumatic tap risk ratio of 0.33 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.82) and p=0.02. The included studies had low to moderate quality; the studies differed based on mean age and with variability on outcome definition.

Conclusions and relevance

This meta-analysis suggests that ultrasound imaging has no effect in increasing lumbar success but is beneficial in reducing the risk of traumatic taps in neonates and infants.

Trial registration number

CRD42017055800.

Keywords: Child, Humans, Spinal Puncture, Ultrasonography

Background

Lumbar puncture (LP) is a common procedure in the care of children as it aids in the diagnosis of infectious, inflammatory, haemorrhagic or neoplastic diseases while also being crucial in the delivery of therapeutic intrathecal medications or in the management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.1–5

The goal of performing an LP is to access the subarachnoid space.5 The standard or palpation method of performing an LP involves positioning the patient, identifying the L4/L5 intervertebral space and advancing a spinal needle into subarachnoid space until cerebrospinal fluid is obtained.6 7 The procedure can be challenging due to multiple factors like patient size, and failure rates up to 65% have been reported.7–9 LP failure can result in increased patient discomfort when there are many attempts, increased hospital admissions and prolonged antibiotic use hence the interest in increasing the likelihood of successful LPs.10–15

Ultrasonography is being used increasingly in paediatric inpatient and emergency care. Ultrasound uses sound waves to identify body structures. It has no radiation, is cheap and can be performed with little training.16 17 It is therefore hypothesised that the use of ultrasonography to identify the optimal vertebral interspace level and ideal puncture point might lead to increased success of LPs.18–20

In adults, there are many randomised clinical trials and a few systematic reviews on the use of ultrasonography for LP and these studies suggest that using ultrasonography in performing LPs are beneficial.17 21 22 Most of the LPs performed in paediatrics are in neonates and infants. The few studies in this population have conflicting results on benefits of ultrasound imaging for paediatric LP that this review aims to address.23–26 The objective of this meta-analysis is to assess if ultrasound imaging increases the success of LP procedures and to assess any associated complications of the procedure when compared with the palpation method.

Methods

The study was registered in PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews. Covidence (www.covidence.org) was used for study selection, data abstraction and then exported into RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Search strategy

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols guidelines were used in the preparation of the systematic review and meta-analysis.24 We searched the National Library of Medicine through PubMed (from 1990 to March 2018), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (to the first quarter of 2018) and ClinicalTrials.gov (to the first quarter of 2018). We also searched Embase, Scopus and Web of science (to the first quarter of 2018). The search was done without any restrictions by language or publication status. The search strategy was conducted with the aid of the institutional librarian. The following search terms were used: ‘ultrasound’ and ‘lumbar puncture’. The search strategy also included multiple synonyms, abbreviations and related keywords for each of these terms. We also examined the reference lists of retrieved original and review articles for any additional studies.

Study selection

Two authors, AO and JO, independently assessed and identified articles for eligibility and collected data for this study. Articles thought to be potentially eligible were reviewed in full and assessed for eligibility by both reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

To be eligible for inclusion this review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials in any setting conducted in children from birth till the age of 1 year and in humans comparing the use of ultrasound imaging to standard palpation techniques while performing an LP. The studies needed to report on any of the primary or secondary outcomes defined below.

We excluded studies in adults, children older than 1 year of age and studies using other radiological interventions like fluoroscopy.

Outcome measures and definitions

We based our definitions on similar definitions in a similar review.17

Our primary objective was to determine whether ultrasound imaging reduces the risk of failed LPs in children in comparison with the traditional method. A failed LP occurs when there is failure to obtain cerebrospinal fluid after an LP procedure.

Our secondary objectives were to determine whether the use of ultrasound imaging has any effect on the risk of traumatic taps, number of needle reinsertion or redirection and on procedure duration. A traumatic LP was defined as visible blood aspiration or a red blood cell count (RBC) in the cerebrospinal fluid above an appropriately defined threshold. Needle redirections and reinsertions occur during the procedure and refer to any needle adjustments or full withdrawal with new skin puncture respectively during the procedure. The length of time in seconds that the procedure takes is the procedure duration.17

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed using a standardised data collection tool by AO and OF. Data were collected about the year of publication, country of study, population and setting, timing of ultrasound imaging (preprocedure vs real time) and type of ultrasound device. We also extracted data relevant for meta-analysis. All disagreements were resolved with consensus. We contacted authors to obtain additional or missing data.

Assessment of risk for bias

Two reviewer authors (OO and CO) independently and in duplicate assessed the risk for bias in each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.27 The risk for bias was assessed using the following key criteria: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of assessors and attrition bias. We assessed each criterion as having a low, high or unclear risk for bias. An overall risk for bias was determined for each study according to the criteria suggested by Higgins and Green.27 Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data synthesis and analysis

We reported the primary outcome as dichotomous data (failure: yes/no) and obtained risk ratios with 95% CIs. A risk ratio less than 1 suggests that ultrasound was better than traditional method. For the secondary outcomes, we also coded as dichotomous data calculated the risk ratio with a risk ratio less than 1 indicating benefit.27

Assessment of heterogeneity

Our findings were represented in a random effect model, and we calculated the I2 statistic, which provides useful summary of the impact of heterogeneity. We considered an I2 statistic of 50% or more as indicative of a substantial level of statistical heterogeneity.27

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to explore whether methodological differences in the studies were related to statistical heterogeneity. Whenever significant heterogeneity existed, we looked for plausible reasons to explain the difference and carried out sensitivity analysis excluding that study whenever appropriate.

We also planned subgroup analysis for the effect of ultrasound imaging by

Experience/expertise of performer (resident vs attending).

Study setting (academic/university vs non-academic/community).

Assessment of reporting/publication biases

We could not assess the risk of publication bias as planned as we had fewer than 10 studies.28

Summary of findings table and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE)

We graded the overall quality (certainty) of the evidence for each outcome by using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach classifies the quality of evidence into four categories: high, moderate, low and very low, taking into account the study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias, large effect size, dose–response effect and confounding.29 Using this approach, we graded the quality of the evidence of the following outcomes: (1) risk of failure and (2) risk of traumatic tap. We then used the GRADE software to construct a’ Summary of findings’ table.

Results

Results of the search

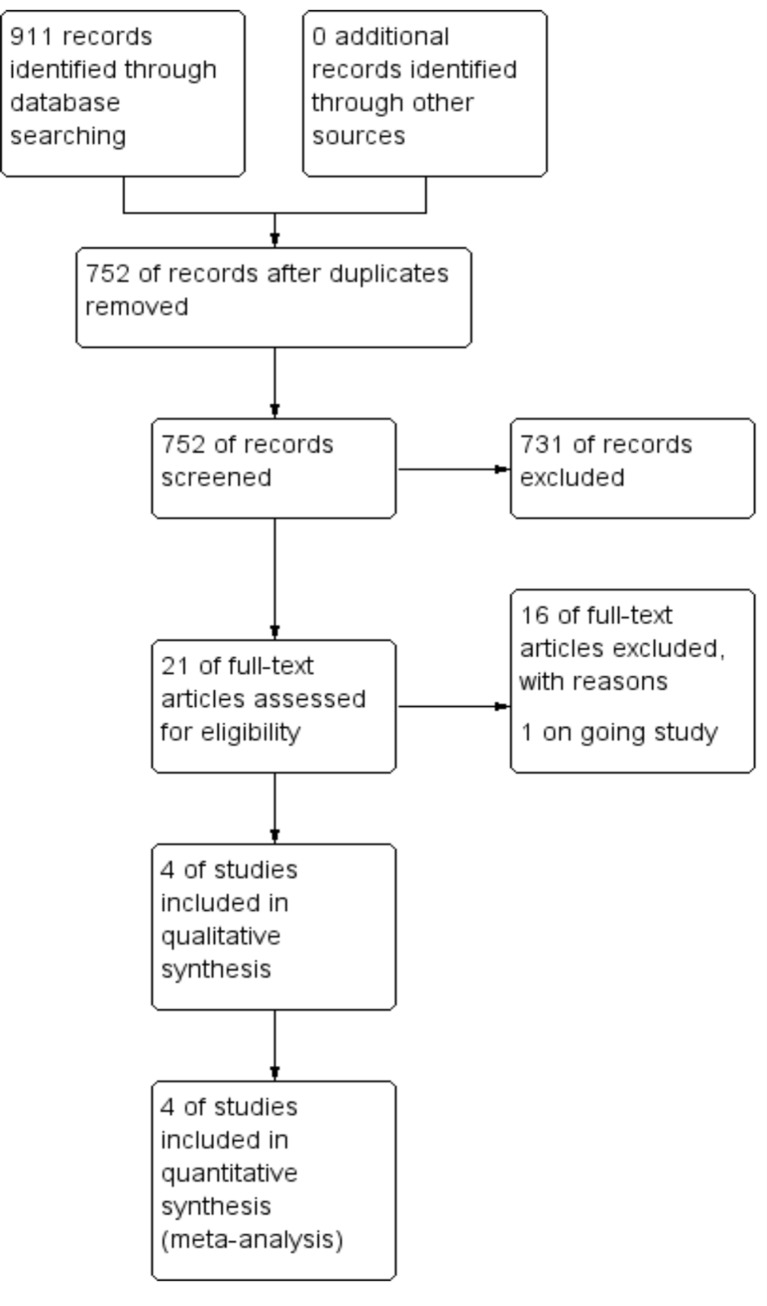

Seven hundred and fifty-three abstracts and titles were screened after duplicates were removed for potentially relevant studies. We then selected 22 articles for full-text review and further selected four studies that met criteria for inclusion in the review. The study flow is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Included studies

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the four included studies. The studies were published between 2015 and 2018, in English language and compared ultrasonography with palpation for LPs. In total, there were 277 participants randomly assigned to ultrasound imaging (n=136) or the traditional/palpation method (control=141). All studies were randomised trials. One study26 was published as a reply to another study, but it had enough information about its methods for inclusion in this review. All the included studies were performed in paediatric emergency departments in the USA.23–26

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Number (ultrasound/control) | Criteria | Baseline demographics and differences | Setting | Ultrasound timing and type | LP performer expertise | Patient position during LP |

| Lam et al

26

(USA) |

26 (11/15) (planned 120) |

<12 months, no previous back surgery, no informed consent. | Median age: 24 days. | ED or paediatric ward. | Preprocedural; Sonosite M-turbo (Bothell, Washington, USA) or Zonare Z.one (Mountain View, California, USA). | All LPs but one by paediatric residents. | N/A |

| Kessler et al

25

(USA) |

79 (39/40) | <90 days, stable, no spinal dysraphism. | Mean age UALP vs SLP: 30 days versus 25 days. | ED. | Preprocedural. | Resident, PEM fellow, attendng. | N/A |

| Gorn et al

23

(USA) |

43 (21/22) (planned 46) | <60 days, no known abnormality of the spine and/or a VP shunt. | Median age lower in UALP group 38 days versus 45 days. | ED. | Preprocedural; Siemens Sonoline G40 (Siemens Corp). | N/A | Lateral decubitus proposed in methods (not available in results). |

| Neal et al

24

(USA) |

128 (64/64) | <6 months, no known abnormality of the spine, English speaking. | Median age 29 days; more males and more procedures in sitting position in UALP. | ED. | Preprocedural; Mindray M7 (Mindray, New Jersey, USA). | Students, residents, NP, PEM fellows and PEM attendings. | Lateral decubitus and sitting. |

ED, emergency department; LP, lumbar puncture; N/A, not available; NP, nurse practitioner; PEM, paediatric emergency medicine; UALP, ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture; VP, ventriculoperitoneal.

Male and female participants were in all the included studies, and all studies except one26 mentioned that they excluded participants with known spinal cord anomalies. The age distribution was not uniform as studies limited participants to 60 days,23 90 days,25 6 months24 and 1 year.26

Performers of the LPs varied within and between studies from medical students to nurse practitioners, residents, fellows and attendings. All the studies involved preprocedural and not real-time ultrasound guidance. Ultrasonography was performed by trained non-radiologists for the purpose of the studies with one study,25 particularly training frontline paediatric ED clinicians.

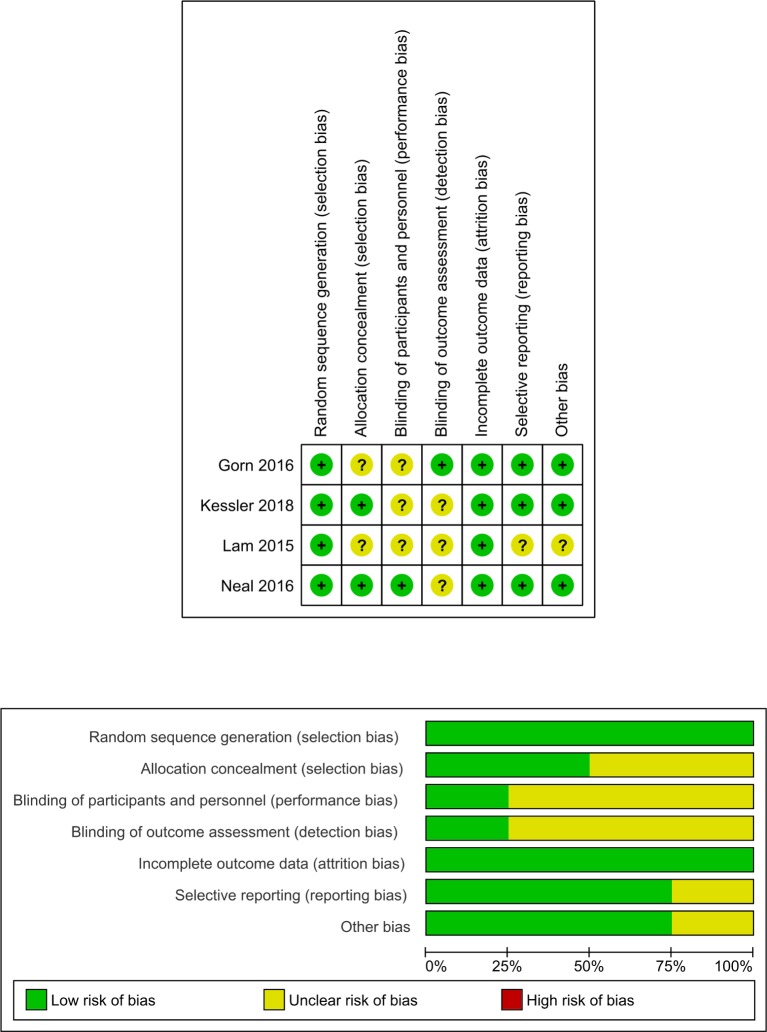

Risk of bias of included studies

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias summary and judgments about each risk of bias domain per included study. All studies used blocked randomisation.23–26 Two studies24 25 also concealed participant enrolment. Only one study23 was able to perform blinding of LP performers. To blind performers, this study performed ultrasonography on all the participants. None of the studies implemented double-blinding; however, the effect of not double-blinding is limited in these studies.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment.

Effects of the intervention

Table 2 contains the summary of main findings and quality of evidence.

Table 2.

Summary of findings

| Ultrasound imaging compared with palpation method for neonates and infants getting a lumbar puncture | ||||||

|

Patient or population: neonates and infants getting a lumbar puncture. Setting: ED or paediatric ward. Intervention: U=ultrasound imaging. Comparison: palpation method. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) |

No. of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Risk with palpation method | Risk with ultrasound imaging | |||||

| Risk of failure | 163 per 1000 |

95 per 1000

(41 to 294) |

RR 0.58

(0.25 to 1.80) |

277 (4 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Ultrasound imaging reduces the risk of failure when performing a lumbar puncture. |

| Risk of having a traumatic tap | 256 per 1000 |

136 per 1000

(85 to 213) |

RR 0.53

(0.33 to 0.83) |

308 (4 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate* |

Ultrasound imaging reduces the risk of a traumatic tap when performing a lumbar puncture. |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence.

High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect

Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

*The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

RCT, randomised clinical trial; RR, risk ratio.

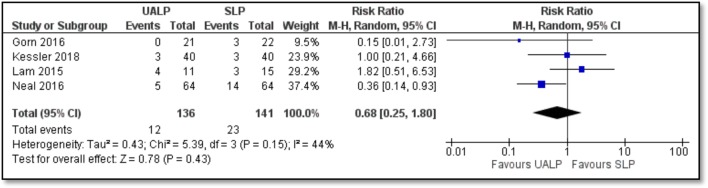

Primary outcome

The primary outcome, procedure failure, included four studies with 277 randomised patients as shown in table 2 and figure 3. The analysis showed that the use of ultrasound imaging reduced the risk failed LP procedures in children when compared with palpation method, risk ratio of 0.68 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.80; p=0.43). However, this reduction was not statistically significant. The quality of this evidence was judged as moderate given there was some imprecision in the included studies as denoted by some of the wide CIs of the included studies. The studies were statistically homogenous I2=44% (p=0.15).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of risk of failure. SLP, palpation lumbar puncture; UALP, ultrasound assisted lumbar puncture.

Sensitivity analysis

Due to the lack of significant heterogeneity, no further analysis was required.

Subgroup analysis

Given the lack of further heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was not indicated.

Furthermore, for the primary outcome, there was no difference in the included studies related to study setting as there were mostly in academic centres nor expertise of the provider as they all had residents in training.

Explanations

Studies had different definitions for traumatic tap leading to some imprecision and so downgraded for that

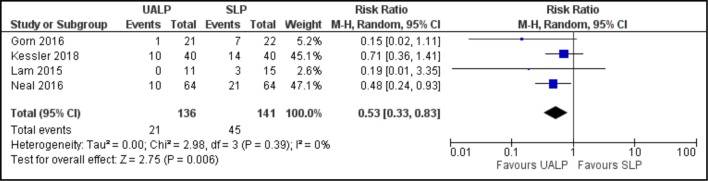

Secondary outcomes

Risk of traumatic tap: ultrasound guided LPs in children significantly reduced the risk of having a traumatic tap when compared with the palpation method (RR=0.53, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.83) with low heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%) as shown in figure 5. Ultrasound guidance would result in 5–18 fewer traumatic LPs in every 100 neonates and infants when compared with the palpation method as presented in table 2 and figure 4. The quality of this evidence was judged as moderate given there was some imprecision in the included studies.

Needle insertion attempts: the studies23–26 looked at the number of needle attempts, and they found that there was no difference in both groups in terms of the number of attempts required to obtain CSF successfully during a diagnostic LP. Gorn et al 23 found that the number of attempts between the ultrasound and palpation groups were not significantly different. Neal et al 24 reported that the median number of attempts was 1 in the ultrasound group and 2 in the palpation group, but this was not statistically significant. Similarly, Kessler et al 25 reported two attempts in both the ultrasound and palpation groups. Lam and Lambert26 reported a median of 1.5 attempts compared with two attempts in the ultrasound group as against the palpation group, respectively.

Needle redirections: no study addressed the number of redirections.

Length of procedure: two studies25 26 looked at differences based on length of procedure, and both studies could not find a statistically significant difference in the median duration of the procedures in both the intervention and control groups. Kessler et al 25 reported a median of 1.6 min (IQR=0.8–13.4) versus 4.2 min (IQR=0.8–5.2) in the ultrasound versus the palpation group without any statistical significance especially when median ultrasound duration of 4.6 min (IQR=3–6.8) is added. Similarly, Lam and Lambert26 had median duration of 197 s versus 146 s in the ultrasound versus the palpation group, respectively, without any statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of risk of traumatic lumbar puncture. UALP, ultrasound assisted lumbar puncture; SLP, palpation lumbar puncture.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Results of our review shows there is no significant effect reducing the number of failed LP procedures in neonates and infants when ultrasonography is used. However, ultrasound imaging significantly reduces the risk of traumatic LPs in children. A possible explanation for this finding is that ultrasound imaging can identify anatomic structures that need to be avoided in order to have increased success and less chance of nicking a vessel. Our review did not have enough studies to demonstrate objective evidence on the benefit of ultrasound in reducing the number of attempts in an LP procedure, and there was no effect on the duration of the procedure. However, in this review, the overall failure rate for LP was 11% when combining both groups. When compared with reported failure rates of 35%–65% in other studies, this represents a high success rate and that may affect the perceived benefit of the intervention.

Strength and limitations

This strength of this review lies in the broad inclusion criteria and design that ensures that the review is representative of the available literature on this topic. However, given the relatively few number of available studies, we were not able to fully explore the effects of certain subgroups.

The inclusion of front-level providers like medical students, residents, fellows, NPs and attendings in the included studies is a strength of this review as these are the usual performers of LPs in medical care.

Our review does have potential limitations. First, all studies had sample sizes less than 100 participants, and the risk of effect overestimation is greater in studies with small sample sizes. Furthermore, the risk of bias assessment shows that participant blinding was not a part of the included studies. Although blinding participants in an ultrasound study is very difficult, one study did attempt single blinding by performing ultrasound on all participants.23 Next, there was no standard definition for some of the study outcomes such as a traumatic tap with studies choosing RBC of 400 versus 1000 versus 10 000 for the definition of a traumatic tap. We addressed this by using the study threshold and extracting the data as dichotomous variables. The included studies used non-radiologist for the ultrasound procedure that supports the theory that point-of-care ultrasound can be applied to real-world scenarios. Finally, we were unable to determine the use of ultrasound on clinically relevant information like pain, postprocedure headaches, patient satisfaction and cost-effectiveness, and in cases where the LP is done to rule out infections, we have no information on rate of hospital admission/readmission, duration of antibiotic exposure and length of stay. We believe that these clinical endpoints should be the aim of further interventions that apply the use of ultrasound for LP in children.

Comparison with other studies

There are many adult studies and one meta-analysis in adult and children looking at the use of ultrasound in LPs.17 That meta-analysis by Shaikh et al only included one study that was performed in children, and it was for epidural catheterisation. Thus, this is the first meta-analysis and systematic review of the use of ultrasound imaging for LP in children. Our results are congruent with similar studies in adults and the previously mentioned meta-analysis as they showed that ultrasound imaging may be useful for LPs. No systematic reviews have looked at the use of ultrasound imaging for missed LPs, but other imaging techniques have been studied especially fluoroscopy.

Implications for practice and further research

Fluoroscopy has been broadly studied, and in many paediatric healthcare centres, it is used as the next line of intervention when standard LP fails. Ultrasound offers the advantage of being radiation free, which is particularly important in children as we aim to limit radiation exposure. It is also cheap, mastery can be established after a few attempts and it is portable. Thus, we would like to see redirection of paediatric centres from fluoroscopy to ultrasound for failed LPs.

Future research should also focus on using standardised definitions for outcomes, on cost-effectiveness and other clinically relevant outcomes like pain patient and physician satisfaction.

In summary, the current available evidence suggests that ultrasound imaging does not improve the success of LP in neonates and infants, but it does help in reducing traumatic taps.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Lynn Kysh (BA MLIS), who helped implement a thorough search of all potentially relevant studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: AO wrote the first draft, and no form of payment was made for the production of this paper. JO and CO performed extensive full text review as well as reviewing the key aspects of the paper. OF and OO were responsible for the assessment of bias and statistical analysis of the paper. All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors and, to the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists. We have included acknowledgements after the conclusion statement. Each author listed on the manuscript has seen and approved the submission of this final version of the manuscript. In addition, each author takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bürger B, Zimmermann M, Mann G, et al. Diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid examination in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: significance of low leukocyte counts with blasts or traumatic lumbar puncture. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:184–8. 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delerme S, Castro S, Viallon A, et al. Meningitis in elderly patients. Eur J Emerg Med 2009;16:273–6. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283101866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mintegi S, Benito J, Astobiza E, et al. Well appearing young infants with fever without known source in the emergency department: are lumbar punctures always necessary? Eur J Emerg Med 2010;17:167–9. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283307af9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonadio W. Pediatric lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. J Emerg Med 2014;46:141–50. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J. How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis? JAMA 2006;296:2012–22. 10.1001/jama.296.16.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. López T, Sánchez FJ, Garzón JC, et al. Spinal anesthesia in pediatric patients. Minerva Anestesiol 2012;78:78–87. 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Neuman MI. Risk factors for traumatic or unsuccessful lumbar punctures in children. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:762–71. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kessler DO, Auerbach M, Pusic M, et al. A randomized trial of simulation-based deliberate practice for infant lumbar puncture skills. Simul Healthc 2011;6:197–203. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318216bfc1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conroy SM, Bond WF, Pheasant KS, et al. Competence and retention in performance of the lumbar puncture procedure in a task trainer model. Simul Healthc 2010;5:133–8. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181dc040a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seeberger MD, Kaufmann M, Staender S, et al. Repeated dural punctures increase the incidence of postdural puncture headache. Anesth Analg 1996;82:302–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srinivasan L, Harris MC, Shah SS. Lumbar puncture in the neonate: challenges in decision making and interpretation. Semin Perinatol 2012;36:445–53. 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. te Loo DM, Kamps WA, van der Does-van den Berg A, et al. Prognostic significance of blasts in the cerebrospinal fluid without pleiocytosis or a traumatic lumbar puncture in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: experience of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2332–6. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ozdamar E, Ozkaya AK, Guler E, et al. Ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture in pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanegaye JT, Soliemanzadeh P, Bradley JS. Lumbar puncture in pediatric bacterial meningitis: defining the time interval for recovery of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens after parenteral antibiotic pretreatment. Pediatrics 2001;108:1169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pingree EW, Kimia AA, Nigrovic LE. The effect of traumatic lumbar puncture on hospitalization rate for febrile infants 28 to 60 days of age. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:240–3. 10.1111/acem.12582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayes J, Borges B, Armstrong D, et al. Accuracy of manual palpation vs ultrasound for identifying the L3-L4 intervertebral space level in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2014;24:510–5. 10.1111/pan.12355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaikh F, Brzezinski J, Alexander S, et al. Ultrasound imaging for lumbar punctures and epidural catheterisations: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f1720 10.1136/bmj.f1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mofidi M, Mohammadi M, Saidi H, et al. Ultrasound guided lumbar puncture in emergency department: Time saving and less complications. J Res Med Sci 2013;18:303–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang PI, Wang AC, Naidu JO, et al. Sonographically guided lumbar puncture in pediatric patients. J Ultrasound Med 2013;32:2191–7. 10.7863/ultra.32.12.2191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bruccoleri RE, Chen L. Needle-entry angle for lumbar puncture in children as determined by using ultrasonography. Pediatrics 2011;127:e921–e926. 10.1542/peds.2010-2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peterson MA, Pisupati D, Heyming TW, et al. Ultrasound for routine lumbar puncture. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:130–6. 10.1111/acem.12305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strony R. Ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture in obese patients. Crit Care Clin 2010;26:661–4. 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gorn M, Kunkov S, Crain EF. Prospective investigation of a novel ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture technique on infants in the pediatric emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:6-12 10.1111/acem.13099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neal JT, Kaplan SL, Woodford AL, et al. The effect of bedside ultrasonographic skin marking on infant lumbar puncture success: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kessler D, Pahalyants V, Kriger J, et al. Preprocedural Ultrasound for Infant Lumbar Puncture: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25:1027–34. 10.1111/acem.13429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lam SH, Lambert MJ. In reply: ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture in pediatric patients. J Emerg Med 2015;48:611–2. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higgins JPT, Green S. No title. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated], 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.