Abstract

The fetal consequences of gestational engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure are unclear. The placenta is a barrier protecting the fetus and allowing transfer of substances from the maternal circulation. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of maternal pulmonary titanium dioxide nanoparticle (nano-TiO2) exposure on the placenta and umbilical vascular reactivity. We hypothesized that pulmonary nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure increases placental vascular resistance and impairs umbilical vascular responsiveness. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed via whole-body inhalation to nano-TiO2 with an aerodynamic diameter of 188 ± 0.36 nm. On gestational day (GD) 11, rats began inhalation exposures (6h/exposure). Daily lung deposition was 87.5 ± 2.7 μg. Animals were exposed for 6 days for a cumulative lung burden of 525 ± 16 μg. On GD 20, placentas, umbilical artery and vein were isolated, cannulated, and treated with acetylcholine (ACh), angiotensin II (ANGII), S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine (SNAP), or calcium-free superfusate (Ca2+-free). Mean outflow pressure was measured in placental units. ACh increased outflow pressure to 53 ± 5 mm Hg in sham-controls but only to 35 ± 4 mm Hg in exposed subjects. ANGII decreased outflow pressure in placentas from exposed animals (17 ± 7 mm Hg) compared to sham-controls (31 ± 6 mm Hg). Ca2+-free superfusate yielded maximal outflow pressures in sham-control (63 ± 5 mm Hg) and exposed (30 ± 10 mm Hg) rats. Umbilical artery endothelium-dependent dilation was decreased in nano-TiO2 exposed fetuses (30 ± 9%) compared to sham-controls (58 ± 6%), but ANGII sensitivity was increased (−79 ± 20% vs −36 ± 10%). These results indicate that maternal gestational pulmonary nano-TiO2 exposure increases placental vascular resistance and impairs umbilical vascular reactivity.

Keywords: engineered nanomaterials, titanium dioxide nanoparticles, microcirculation, placenta

Introduction

While the field of nanotechnology has seen a tremendous expansion and growth in recent years (Paull et al., 2003), a more thorough understanding of maternal and fetal effects associated with engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure warrants deeper investigation and is of key relevance for their safe design and regulation.. Pregnancy is characterized by rapid anatomic microvascular adaptations (Osol and Mandala, 2009), particularly of the maternal circulation that are essential for healthy gestation, and also represents a critical window of sensitivity to toxicological insults. These changes include vasculogenesis, the de novo formation of blood vessels by endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenesis, the development of new vessels from pre-existing ones. All these mechanisms cause an increase in overall vascular diameter and number which results in a significant reduction in the vascular resistance of the maternal-fetal circulation. Expansive remodeling of the maternal circulation is a fundamental process for a healthy pregnancy and impairmenst in this finely regulated process may compromise maternal and/or fetal health. Indeed, insufficient growth and development of the uteroplacental circulation results in placental under-perfusion and has been associated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (Krebs et al, 1996) and pre-eclampsia (Granger et al., 2001).

The study of developmental and reproductive effects of ENM exposures in various animal models has in recent years gained more attention (Ema et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2017). We have reported that in rats, inhalation of ~11.3 mg/m3 of nano-TiO2 for 7 days during the second half of gestation resulted in an impairment in endothelium-dependentfetal vascular reactvity, and maternalinhalation exposure for >7 days decreases pup number and mass (Stapleton et al., 2013, Stapleton et al., 2018). Similarly, inhalation of 10.6 mg/m3 nano-TiO2 during late gestation (average 6.8 days, 5 h/day) was associated with an impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation and active mechano-transduction in uterine arteries and a reduction in maximal mitochondrial respiration in female offspring (Stapleton and Nurkiewicz, 2014). Additionally, reduced pup weight and litter size (Adamcakova-Dodd et al., 2015) along with persistent cognitive deficits of maternally exposed young adult rats have also been reported (Engler-Chiurazzi et al., 2016), thus highlighting the potential fetal consequence of maternal ENM exposure during gestation.

One of the most critical components of the maternal-fetal vascular axis is the placenta. The placenta is a transient barrier organ with significant functions that are crucial for fetal development. The placental cellular barrier at the maternal-fetal interface consists of trophoblasts and endothelial cells (Huppertz, 2008). Between these two cell layers, the surrounding tissue is formed primarily by stromal fibroblasts and macrophages (Hofbauer cells). The placenta plays an essential role in the fetal regulation of gas and heat transfer, excretion, metabolism, synthesis and secretion of endocrine hormones, hematopoiesis and immunity (Huppertz, 2008). Additionally, the placenta maintains the balance between the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures in the capillary microcirculation and the interstitial fluid. At full term, the placenta receives >90% of uterine blood flow as a result of significant hemodynamic alterations that result from decreased vascular resistance. This is achieved by anatomical remodeling and functional adjustments such as decreased microvascular tone and increased vasodilatory sensitivity. (Osol and Mandala, 2009). Due to its absence of autonomic innervation, the placental vasculature is completely reliant upon local mechanisms of vascular reactivity in order to support the dynamic requirements for healthy gestation.

Since the development of nanotechnology, the question of maternal-fetal particle translocation has been present. In vitro, fluorescently labelled carboxylate-modified polystyrene beads with a diameter of up to 500 nm have been shown to cross the placental barrier and induce trophoblast apoptosis (Huang et al., 2015). Silica nanoparticles having a diameter of less than 100 nm and nano-TiO2 with a diameter of approximately 35 nm have been shown to cross the placental barriers, potentially resulting in impaired placental function by decreasing the area of the trophoblasts and the length of the villi in the labyrinthine layer of the placenta (Hong et al., 2017).

Placental health and maternal-fetal vascular function are factors recognized as contributors to the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) cannot be over-emphasized (Barker, 2007). Yet, there is a paucity of in-vivo data regarding the effects of pulmonary ENM exposure on local control of placental vascular resistance because it is essentially impossible to directly assess these variables. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine ex-vivo the effects of nano-TiO2 exposure on placental hemodynamics and on the function of the umbilical vasculature. We hypothesized that maternal pulmonary nano-TiO2 exposure results in a significant increase in placental vascular resistance and an impairment in umbilical vascular reactivity. We adopted and modified an established ex-vivo perfusion placental model (Goeden and Bonnin, 2013) to make direct assessments of placental outflow pressure and placental flow rate measured as a function of the inflow pressure. Vascular reactivity of the umbilical artery and vein were directly assessed via pressure myography.

Materials and Methods

Nanomaterial Aerosol Characterization

Nano-TiO2 P25 powder, obtained from Evonik (Aeroxide TiO2, Parsippany, NJ), has previously been shown to be a mixture composed primarily of anatase (80%) and rutile (20%) TiO2, with a primary particle size of 21 nm and a surface area of 48.08 m2/g, and a Zeta-potential of −56.6 mV (Stapleton et al., 2018). Analysis of the elemental composition of the nano-TiO2 was conducted via energy dispersive spectroscopy.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) procedures were performed using a nano-TiO2 exposed 0.2 um polycarbonate filter with a 200 mesh formvar coated copper grid affixed in the center. A wedge-shaped portion of the polycarbonate filter was mounted onto a 13 mm aluminum stub using carbon double stick tape. The sample was sputter coated with gold-palladium for two minutes. The sample was imaged at 5 KeV using a Hitachi S4800 field-emission scanning electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan). For TEM, the exposed grid was removed from the polycarbonate filter, and imaged at 80 KeV on a JEOL 1400 transmission electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Aerosol size distributions were measured from the exposure chamber while the mass concentration was being maintained at 12 mg/m3 with: 1) a high-resolution electrical low-pressure impactor (ELPI+; Dekati, Tampere, Finland), (2) a scanning particle mobility sizer (SMPS 3938; TSI Inc., St. Paul, MN), and (3) an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS 3321; TSI Inc., St. Paul, MN).

Experimental Animals and Whole-Body Inhalation Exposure

Female Sprague – Dawley rats (8–10 weeks, 250–275 grams) were purchased from Hilltop Laboratories (Scottdale, PA) and housed in an AAALAC approved facility at West Virginia University (WVU) with 12:12 h light – dark cycle, 20–26°C, and 30–70% relative humidity. Rats were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of WVU.

Nano-TiO2 aerosols were generated using a high-pressure acoustical generator (HPAG, IEStechno, Morgantown, WV). The output of the generator was fed into a Venturi pump (JS-60M, Vaccon, Medway, MA) which further de-agglomerated the particles. The nano-TiO2 aerosol / air mix then entered the whole-body exposure chamber. A personal DataRAM (pDR-1500; Thermo Environmental Instruments Inc., Franklin, MA) was utilized to sample the exposure chamber air to determine the aerosol mass concentration in real-time. Feedback loops within the software automatically adjusted the acoustic energy to maintain a stable mass concentration during the exposure. Gravimetric measurements were conducted on Teflon filters concurrently with the DataRAM measurements to obtain a calibration factor. The gravimetric measurements were also conducted during each exposure to calculate the mass concentration measurements reported in the study. Bedding material soaked with water was used in the exposure chamber to maintain comfortable humidity (30–70%) and temperature (20–26°C) during the exposure. Sham-control animals were exposed to HEPA filtered air only with similar chamber conditions in terms of temperature and humidity.

To allow for implantation and neovascularization, inhalation exposures were initiated on GD 11. The pregnant rats were exposed to an average target concentration of 12 mg/m3. This concentration was chosen to match our previous late gestation inhalation exposure studies (Stapleton et al., 2013, Stapleton and Nurkiewicz, 2014, Stapleton et al., 2018). To estimate lung dose with ultrafine TiO2 aerosols (Nurkiewicz et al., 2008), we used the equation: D = F·V·C·T, where F is the deposition fraction (10%), V is the minute ventilation (208.3 cc), C equals the mass concentration (mg/m3), and T equals the exposure duration (minutes) (Yi et al., 2013). This exposure paradigm (12 mg/m3, 6h/exposure, 6 days) produced an estimated target lung dose of 525 ± 16 μg. The last exposure was conducted 24 h prior to euthanasia and tissue collection and assessment of microvascular reactivity. These calculations assume total lung deposition and do not account for clearance (MPPD Software v 2.11, Arlington, VA)

Collection and Ex Vivo Perfusion of the Rat Placenta

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas (5% induction, 2–3.5% maintenance). The animals were placed on a heating pad to maintain a 37° C rectal temperature. The trachea was intubated to ensure an open airway and the right carotid artery was cannulated to allow blood pressure measurements and sampling. Following blood sampling, the abdominal cavity of the animal was opened, and the uterine horns were externalized. A placenta with a large and intact portion of the uterine artery was selected, excised and placed in a dissecting dish containing physiological salt solution (PSS) at 4° C. The amniotic sac was subsequently opened, and the placenta was separated from the fetus. The vitelline artery was removed from the umbilical cord which was severed as close as possible to the fetus, preserving the umbilical vasculature for cannulation. The maternal circulation was then tied off using 9–0 silk sutures (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT). After separation of the umbilical artery and vein, the placenta was then transferred to an isolated microvessel chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT).

Both the umbilical artery and vein were cannulated between two glass pipettes (Outer diameter: 175–200 μm, Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT), and tied with 9–0 silk sutures in the chamber. The placenta was perfused with PSS and the chamber was superfused with fresh oxygenated (21% O2/5% CO2) PSS and warmed to 37° C. After a 30-minute equilibration period, the inflow pressure was increased in a stepwise fashion (0 mm Hg, 20 mm Hg, 40 mm Hg, 60 mm Hg and 80 mm Hg). Outflow pressure and flow rate were measured in placentas in normal superfusate and following pre-treatment with acetylcholine (ACh:10−2M), S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine (SNAP: 10−2M), angiotensin II (ANGII: 10−2M) and calcium-free superfusate.

Immunohistochemical Staining of Placental Tissue

Uteri from Sham-controls and nano-TiO2 exposed animals were removed immediately after euthanasia and two placentas per rat were dissected away from the pup and the uterine wall. The placental tissue was immediately placed into a fixative (4% paraformaldehyde) for 3 hours at 4° C and then transferred to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight. Twelve hours later, the tissue was flash frozen and stored at −80° C until sectioned. Placentas were sectioned at 50 μm through the center of the placenta. On day 1 of the protocol, the sections were washed 4 × 5 minutes in 0.1 M PBS to remove excess cryoprotectant and washed overnight at 4° C. The next day, the sections were washed 4 × 5 minutes in PBS, placed in 1% H2O2 for 10 minutes and subsequently washed 4 × 5 minutes in PBS. The tissue was then incubated for at least 1 hour in a blocking solution containing PBS, 20% Triton X-100 (PBSTX) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 20% normal goat serum (NGS) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) in PBS. Tissue sections were placed in a solution containing rabbit anti-Von Willebrand factor (vWF-catalogue number ab6994; dilution 1:2 000; AbCam, Cambridge, MA) in PBSTX and 4% NGS for 16 hours. After incubation with the primary antibody, sections were incubated in a solution containing biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG and a solution containing avidin-biotin horseradishperoxidase conjugate (Vectastain Elite ABC; dilution 1:600; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour. Sections were then washed and incubated for 10 minutes in biotinylated tyramine (TSA) (dilution 1:250; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) in PBS containing 3% H2O2 per 1 mL of solution. After washing, sections were incubated in a solution containing DyLight green 488-streptavidin (1:200, Fisher Scientific) for 1 hour followed by washes and incubation in PBSTX and 4% NGS for at least 1 hour. Sections were incubated in mouse anti-smooth muscle actin (SMA-catalogue number ab 7817; dilution 1:1000; AbCam, Cambridge, MA) in PBSTX and 4% NGS for 16 hours. The next day, sections were incubated in Alexa555 goat anti-rabbit (dilution 1:200; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 hour, washed, mounted on Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific), covered with a coverslip using ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and stored in the dark at 4° C until analysis.

Pressure Myography Vessel Preparation

A placental unit was placed in a dissecting dish with PSS maintained at 4° C. The umbilical cord was cut longitudinally to reveal the artery and vein. The umbilical artery and vein were isolated, transferred to a vessel chamber, cannulated between two glass pipettes, and tied with silk sutures in the chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT). The chamber was superfused with fresh oxygenated (21% O2/5% CO2) PSS and warmed to 37° C. Both vessels were pressurized to 60 mm Hg using a servo control system and extended to the in-situ length. Internal and external vascular diameters were measured using video calipers (Colorado Video, Boulder, CO).

Vascular Reactivity

Vessels were allowed to develop spontaneous tone, defined as the degree of constriction experienced by a blood vessel relative to its maximally dilated state. Vascular tone ranges from 0% (maximally dilated) to 100% (maximal constriction). After equilibration, various parameters of vascular function were analyzed.

Endothelium-Dependent Dilation—vessels were exposed to increasing concentrations of ACh (10−9 - 10−4 M) added to the vessel chamber.

Endothelium-Independent Dilation—increasing concentrations of SNAP (10−9 - 10−4 M) were used to assess vascular smooth muscle responsiveness.

Vasoconstriction—vessels were exposed to increasing concentrations of ANGII (10 −9 - 10−4 M).

The steady state diameter of the vessel was recorded for at least 2 min after each dose. After each dose curve was completed, the vessel chamber was washed to remove excess chemicals by carefully removing the superfusate and replacing it with fresh warmed oxygenated PSS. After all experimental treatments were complete, the PSS was replaced with Ca2+-free PSS until maximum passive diameter was established.

Pressure Myography Calculations

Data are expressed as means ± standard error. Spontaneous tone was calculated by the following equation:

, where Dm is the maximal diameter and Di is the initial steady state diameter recorded prior to the experiment. Active responses to pressure were normalized to the maximal diameter using the following formula:

, where Dss is the steady state diameter recorded during each pressure change. The experimental responses to ACh, PE, and SNP are expressed using the following equation:

, where DCon is the control diameter recorded prior to the dose curve, DSS is the steady state diameter at each dose of the curve. The experimental response to PE is expressed using the following equation:

Wall thickness (WT) was calculated from the measurement of both inner (ID) and outer (OD) steady state diameters at the end of the Ca2+ free wash using the following equation:

Wall-to-lumen ratio (WLR) was calculated using the following equation:

Statistics

Point-to-point differences in the dose response curves of the placentas and umbilical vessels were evaluated using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey`s post-hoc analysis when significance was found. The animal characteristics and vessel characteristics were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc analysis when significance was found. A mixed-effects analysis was used to determine the effect of exposure on placental outflow pressure (GraphPad Prism; San Diego, CA). Wherever sphericity was not met, the Greenhouse-Geiger correction was adopted. A mix-model linear regression was also performed to determine the differences in the slopes between the sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed groups. Significance was set at p < 0.05, n is the number of vessels and placentas, while N is the number of animals.

Results

Aerosol Characterization of Nano-TiO2 and Inhalation Exposures

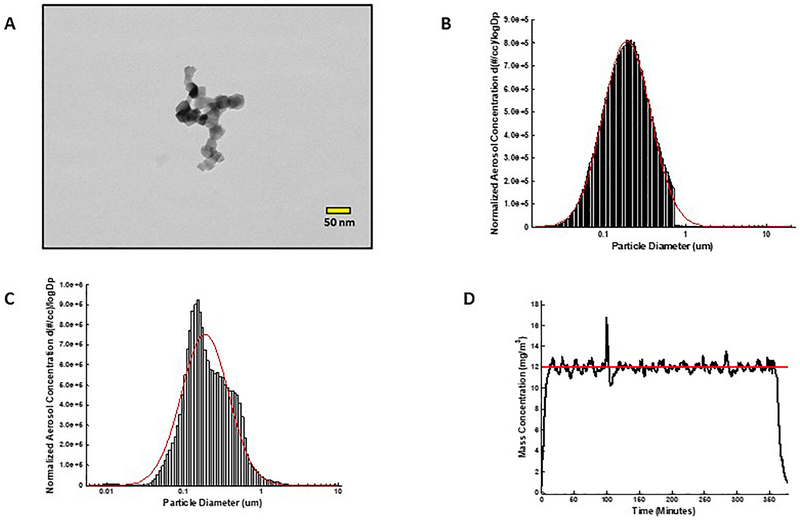

FIGURE 1 A shows a representative field-emission transmission electron microscope image of a nano-TiO2 agglomerate generated during an aerosol exposure. The SMPS and APS data were combined to determine the count median diameter (CMD) using a fitted log normal distribution. The CMD was determined to be 190 nm with a geometric standard deviation (GSD) of 1.97 (FIGURE 1 B). The ELPI High Resolution data indicated a CMD of 188 ± 0.36 nm with a GSD of 2.02 (FIGURE 1 C). The control software regulated the mass concentration of the nano-TiO2 aerosol during exposures. The real-time concentration measurements (with a target concentration of 12 mg/m3) during a typical 6-hour exposure are shown in FIGURE 1 D. Gravimetric results indicated that each pregnant rat was exposed six days (6 hr/day) to an average concentration of 11.7± 1.0 mg/m3. This resulted in an estimated total lung deposition for each rat of 525 ± 16 μg.

Figure 1. Nano-TiO2 aerosol characterization.

(A) Transmission electron microscope image of a typical nano-TiO2 agglomerate generated with the high-pressure acoustical generator, (B) Size distribution of the nano-TiO2 aerosol (mobility diameter) sampled from the exposure chamber using a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS-light grey) and an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS-dark grey, negligible values). The red line represents a log-normal fit of the histogram (Count Median Diameter = 190 nm), (C) Size distribution of the nano-TiO2 aerosol (aerodynamic diameter) using a high resolution electrical low-pressure impactor (ELPI+). The red line represents a log-normal fit of the histogram (Count Median Diameter = 188 ± 0.36 nm). (D) Real-time mass concentration measurements of the nano-TiO2 aerosol during a typical inhalation exposure. The red line represents the target concentration, 12 mg/m3.

Animal and Vessel Characteristics

Age, body weight or number of pups were not different between sham-control and exposure groups (Table 1). Additionally, umbilical artery and vein inner and outer diameter, tone, wall thickness, wall to lumen ratio and calculated wall tension were not affected by maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Interestingly, the umbilical vein passive inner diameter was significantly increased in the maternal nano-TiO2 exposed group (623 ± 40 μm) compared to the sham-control group (543 ± 29 μm). This later point provides evidence that umbilical vascular wall anatomy may be affected by maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation.

Table 1. Animal characteristics.

Characteristics of sham-control (N=8) and maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposed groups (N=10). Values shown are mean ± SEM. Statistics were analyzed with two-way ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05), * vs. Sham-control group.

| N | Age (weeks) | Weight (grams) | Number of Pups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 8 | 12±2 | 310±27 | 6±2 |

| Exposed | 10 | 13±1 | 344±16 | 9±3 |

Table 2. Umbilical artery characteristics.

Characteristics of sham-control and maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposed umbilical arteries (n=12–14). Values shown are mean ± SEM. Statistics were analyzed with two-way ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05).

| n | Inner diameter (μm) | Outer diameter (μm) | Tone (%) | Passive diameter inner (μm) | Passive diameter outer (μm) | Wall Tension (Newton/meter) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 14 | 402±11 | 664±13 | 15±4 | 459±15 | 707±17 | 0.34±0.1 |

| Exposed | 12 | 398±5 | 652±14 | 17±7 | 442±9 | 699±15 | 0.37±0.2 |

Table 3. Umbilical vein characteristics.

Characteristics of sham-control and maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposed umbilical veins (n=8–10). Values shown are mean ± SEM. Statistics were analyzed with two-way ANOVA (P ≤ 0.05), * vs Sham-control group.

| n | Inner diameter (μm) | Outer diameter (μm) | Tone (%) | Passive diameter inner (μm) | Passive diameter outer (μm) | Wall Tension (Newton/meter) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 | 458±30 | 718±38 | 14±1 | 543±29 | 753±38 | 0.32±0.2 |

| Exposed | 8 | 447±16 | 689±14 | 12±3 | 623±40 * | 741±17 | 0.43±0.4 |

Ex Vivo Perfusion of the Rat Placenta

FIGURE 2 A displays a representative ex vivo perfused placenta preparation. An intact placenta (3) was cannulated between 2 glass pipets via the umbilical artery (1) and the umbilical vein (2). The input (arterial) perfusion pressure was held constant (0–80 mm Hg) while vasoactive stimuli were added to the superfusate. Output pressure and flow rate (μL/min) were the dependent variables representing placental resistance. FIGURE 2 B shows a representative image of the traces obtained with the ex vivo perfused placenta preparation. Panel 1 shows the inflow pressure via the umbilical artery (independent variable), while panels 2 and 3 show the outflow pressure and the perfusate placental flow rate (dependent variables). The reduced outflow pressure is the result of placental vascular resistance. Similarly, placental perfusate flow is the function of this pressure differential between the umbilical artery and the umbilical vein.

Figure 2. Ex vivo placental perfusion preparation.

(A) Umbilical artery (1); vein (2); placenta (3). (B) Input (arterial) perfusion pressure (1) is held constant while vasoactive agonists are added. Output pressure (2) and flow (3) (μl/min) are variables responsive to placental resistance.

The outflow pressures in the sham-control and maternal nano-TiO2 exposed placentas were compared. In the normal superfusate, the sham-control placentas displayed a significantly higher outflow pressure compared to those from exposed dams at 60 and 80 mm Hg (FIGURE 3 A). These results confirm that maternal nano-TiO2 exposure during gestation increases placental vascular resistance. Similarly, sham-control placentas displayed higher mean outflow pressures after treatment with ACh compared to nano-TiO2 exposed placentas at 20, 40, 60 and 80 mm Hg (FIGURE 3 B), indicating that the observed increase in placental vascular resistance may be due to an impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation. FIGURE 4 A shows that pulmonary maternal nano-TiO2 exposure did not affect placental endothelial-independent dilation, while ANGII sensitivity was significantly augmented at 20, 40, 60, and 80 mm Hg (FIGURE 4B). Placentas were then treated with calcium-free superfusate (FIGURE 5) to measure maximum vascular dilation. In this case, placentas from nano-TiO2 exposed dams presented a significantly decreased output pressure compared to the sham-control group at all inflow pressures (20, 40, 60, 80 mm Hg). Lastly, FIGURE 6 shows the mean outflow pressure at 80 mm Hg before and following treatment with different vasoactive agents. The mean outflow pressure in pre-treated sham-control placentas was 43 ± 1 mm Hg, while those from exposed animals were 32 ± 3 mm Hg. ACh-treated placentas presented mean outflow pressures of 53 ± 5 mm Hg in sham-controls and 35 ± 4 mm Hg in exposed subjects. SNAP treatment led to mean outflow pressures of 42 ± 8 in sham-controls and 32 ± 9 in nano-TiO2 mm Hg. Treatment with ANGII resulted in a significantly decreased outflow pressure in the placentas from exposed animals (17 ± 7 mm Hg) compared to sham-control placentas (31 ± 6 mm Hg). Lastly, calcium-free superfusate yielded outflow pressures in sham-control and exposed rats of 63 ± 5 mm Hg and 29 ± 10 mm Hg respectively. Linear regression was used to further confirm that these slopes and therefore the physiologic continuum of the pressure-flow responses were significantly different between the sham-control and exposed groups (Supplemental data).

Figure 3. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure impairs endothelium-dependent placental hemodynamics.

Mean outflow pressures were measured in sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals after the inflow pressure was increased in a stepwise manner and set at 0 mm Hg, 20 mm Hg, 40 mm Hg, 60 mm Hg and 80 mm Hg. Nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure altered placental hemodynamics and decreased outflow (venous) pressure in placentas in normal superfusate (A) and placentas treated with ACh (B) (n=8)., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group.

Figure 4. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure does not affect endothelium-independent placental hemodynamics but increases ANGII sensitivity.

Mean outflow pressures were measured in sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals after the inflow pressure was increased in a stepwise manner and set at 0 mm Hg, 20 mm Hg, 40 mm Hg, 60 mm Hg and 80 mm Hg. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure did not affect endothelial-independent placental hemodynamics (A) but increased ANGII sensitivity (B) (n=8). , (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

Figure 5. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation impairs calcium-free placental hemodynamics.

Mean outflow pressures were measured in sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals after the inflow pressure was increased in a stepwise manner and set at 0 mm Hg, 20 mm Hg, 40 mm Hg, 60 mm Hg and 80 mm Hg. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure altered placental hemodynamics and decreased the outflow pressure in placentas placed in calcium-free superfusate (n=8)., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

Figure 6. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure and placental mean outflow pressure.

Mean outflow pressure at 80 mm Hg inflow pressure in both sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed groups and all treatment conditions is shown (n=8)., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

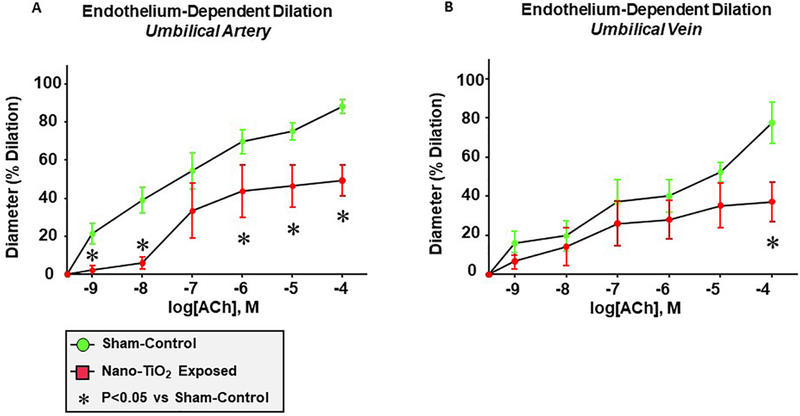

Endothelium-Dependent Dilation

Endothelium-dependent dilation of the umbilical artery was significantly impaired following maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation FIGURE 7A, with a mean dilation of 30.21 ± 8.8% compared to sham-controls (57.9 ± 6.1%). Alternatively, umbilical vein endothelium-dependent dilation FIGURE 7B was impaired only at the highest concentration of ACh (10−4M: 77.4 ± 10.5% vs. 37.23 ± 10.1%). These results suggest that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation during gestation impairs umbilical vascular endothelial function.

Figure 7. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure impairs endothelium-dependent dilation of the umbilical artery and vein.

(A) Endothelium-dependent dilation of the umbilical artery, (B) endothelium-dependent dilation of the umbilical vein from sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals was determined using pressure myography (n=12–14). Statistics were analyzed with two-way ANOVA., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

Endothelium-Independent Dilation

Endothelium-independent dilation of the umbilical artery was impaired in nano-TiO2 exposed animals at 10−7 M (33.3 ± 14.4%) and 10−6 M (43.7 ± 13.7%) of SNAP compared to sham-controls (53.1 ± 13.5%, 68.3 ± 14%) (FIGURE 8 A). In contrast to these findings, no point to point differences were seen in endothelium-independent dilation between sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed groups in the umbilical vein (FIGURE 8 B).

Figure 8. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure impairs endothelium-independent dilation of the umbilical artery and vein.

(A) Endothelium-independent dilation of the umbilical artery, (B) endothelium-independent dilation of the umbilical vein from sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals was determined using pressure myography (n=12–14)., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

Angiotensin II Sensitivity

Umbilical vessels were then treated with increasing concentrations of ANGII, a vasoactive agent that has been strongly implicated in pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension [17]. The umbilical artery from maternal nano-TiO2 exposed rats showed a remarkable increase in vasoconstriction (−79 ± 20.6%) compared to sham-controls (−36 ± 10.3%) (FIGURE 9 A). Interestingly, no differences were seen in the response of the umbilical vein to ANGII between the sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed groups (FIGURE 9 B).

Figure 9. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure increases ANGII sensitivity of the umbilical artery.

(A) ANGII dose-response curve of the umbilical artery (A) and vein (B) from sham-control and nano-TiO2 exposed animals was determined using pressure myography (n=12–14)., (P ≤ 0.05) * vs. sham-control group

Placental Immunohistochemistry

Figure 10 A is a representative cross-sectional image of a placenta from a maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposed dam. The tissue was stained with DAPI to visualize the nuclei of the cells present in the placenta. Co-staining of vWF and SMA was conducted to determine the localization of endothelial cells and to identify the blood vessels forming the placental microvascular circuit. An enlarged (40×) image of a placental microvessel is also shown (FIGURE 10 B). Immunohistochemistry of the placenta was conducted to: a) visualize the microvascular architecture in support of the hypothesis that the observed changes in outflow pressure may be ascribed to vasoactive responses, and b) verify the presence of the vascular endothelium. Future studies using this co-staining technique will be used to determine the impact of maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure on placental vascular density.

Figure 10. Placental immunohistochemistry.

Smooth muscle actin is green, Von-Willebrand Factor is red, and DAPI nuclear staining is blue. (A) Representative image showing immunohistochemistry of a placental section from maternal nano-TiO2 exposed animal. The purpose was to identify the microvascular architecture and the structural components of the placenta. (B) An enlarged (40×) image of a placental microvessel displaying an intact endothelium (green).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the effects of maternal ENM inhalation exposure on placental hemodynamics. Herein, we also present a novel microvascular preparation to study placental perfusion, adapted from a murine microscopy model (Goeden and Bonnin, 2013). The salient findings are that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure during gestation results in altered placental vascular reactivity and resistance. While the systemic microvascular effects of pulmonary ENM inhalation exposure have been previously reported by our group (Abukabda et al., 2017; Minarchick et al., 2015; Mandler et al., 2018) and others (Thompson et al., 2014), the maternal-fetal vascular continuum remains severely understudied. Impairments in endothelium-dependent dilation in the uterine microcirculation (Stapleton et al., 2014) and umbilical vessels (Vidanapathirana et al., 2014) caused by ENM exposure reflect the importance of filling this knowledge gap.

We observed that the fetal consequence of maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation during gestation manifests largely as placental and umbilical vascular dysfunction. However, we do not report on other parameters of adverse fetal health outcomes herein. Nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure has also been shown to be able to migrate to the uterus and induce fetal resorption and negatively affect normal fetal development (Parivar et al., 2015). Furthermore, nano-TiO2 exposure is associated with a marked reduction in placental weight, fetal weight and number and fetal dysplasias (Hong et al., 2017).

Other maternal ENM exposures have been shown to induce negative fetal consequences. ENM transfer across the human placenta has been reported (Wick et al., 2010); however, the fetal consequences are unclear. In animal models, fetal consequences of maternal ENM exposures have been reported. Maternal inhalation exposure to 230 μg/m3 of cadmium oxide nanoparticles resulted in a decrease in the incidence of pregnancy by 23%, diminished placental weight and delayed neonatal growth (Blum et al., 2012). Additionally, intragastric administration of hydroxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes in pregnant mice led to the development of skeletal defects, reduced ossification and morphological abnormalities (Philbrook et al., 2011). Pulmonary exposure to nanosilica with a primary diameter of 70 nm caused significant fetal resorption and inhibited fetal growth (Yamashita et al., 2012). Common to these observations are a dependency on alterations in maternal and fetoplacental vascular physiology.

Microvascular resistance and blood flow are inversely proportional. The fetoplacental vasculature governs nutrient, gas and waste exchange and its characteristic low vascular resistance is essential for fetal health. Alterations in these conditions contribute to increased placental resistance and have been associated not only with preeclampsia, but also IUGR (Learmont and Poston, 1996). The umbilical artery and placental arterial tree are responsible for ~57% of the total fetoplacental resistance, while ~17% is attributable to the capillary bed surface area, and the remaining ~26% to the venous tree and umbilical vein (Rennie et al., 2017). In FIGURES 3–6, an elevated placental resistance is evident after maternal nano-TiO2 exposures in the form of decreased umbilical vein outflow pressure under multiple stimuli. This reflects an increase in the pressure differential across the tissue. If such an increase occurs prior to the placental villus, over-perfusion will result. Alternatively, if this increase occurs post-villus, then under-perfusion may result. In either regard, placental homeostasis will likely be disturbed, thus creating a hostile gestational environment.

Due to its lack of autonomic innervation, cumulative fetoplacental resistance is the result of local mechanisms on vascular smooth muscle tone that ultimately influence blood flow regulation. Therefore, any impairment in reactivity of the arterial and venous ends of the fetoplacental vasculature will significantly affect fetoplacental resistance and may compromise fetal health. Our results reflect that endothelium-dependent dilation in the maternal-fetal circulation is impaired by maternal ENM inhalation exposure. NO plays a particularly crucial role in maintaining the low basal tone of the maternofetal circulation, as reflected by NO synthase inhibitor infusion studies that increase placental perfusion pressure (Learmont and Poston, 1996). It is germane to indicate that such an NO dependency most likely exists in the maternal microvascular circuit as NO signaling is not fully active in early microvascular development (Nurkiewicz et al 2004). This phenomenon is also observable in the current study where ACh treatment did not significantly increase placental outflow pressure vs the normal superfusate response (FIGURE 3 A vs 3 B). Other pathways that may be involved include the potent vasoactive prostanoids, but previous experiments have shown that infusion of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin does not alter perfusion pressure of isolated placentas (Learmont and Poston, 1996).

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is an equally important contributor to blood pressure regulation as well as sodium and fluid homeostasis. The placenta possesses an autonomous, local RAS which has been associated with increased ANGII production in IUGR and preeclampsia (Shah, 2005). Within the placenta, the predominant effects of ANGII (e.g vasoconstriction, angiogenesis and cell growth) are mediated by one of its cognate receptors, the AT1 receptor. Alternatively, the AT2 receptor reduces endothelial proliferation, migration, apoptosis and stimulates vasodilation. In murine models of preeclampsia knocking out the AT1 receptor results in lower blood pressure in the second trimester, whereas knocking out the AT2 receptor increases maternal blood pressure (Takeda-Matsubara, 2004). Furthermore, At1 and At2 receptors have been shown to be expressed in vascular smooth muscle of the umbilical cord and the placenta (Takeda-Matsubara, 2004). An imbalance between these two receptor populations in the maternal-fetal circulation resulting in an increased expression of AT1 receptors has been observed in preeclamptic placentas (Li and Yuan, 2012) and may explain the increase in sensitivity in nano-TiO2 exposed dams by both placentas and the umbilical artery observed in this work. Future studies are therefore required to determine the role of the maternal-fetal local RAS in the microvascular effects described herein.

There are several limitations to the ex-vivo perfused placental preparation adopted in this study that must be considered. First, deterioration and breakdown of the placental tissue occurs very rapidly once removed from the maternal environment. Therefore, this technique requires rapid mounting of the placental units onto the pressure myography chambers in order to minimize the deterioration of the tissue prior to and during experimentation. Second, measurements of the outflow pressure were conducted blindly without real-time visualization of the changes in the placental microcirculation. Lastly, the anatomical differences (Hafez, 2017) between the human and rodent placentas indicate that caution should be exercised when extrapolating the results of the current study to humans. However, despite these differences, the vascular circuitry of the rodent placenta remains very representative of the human maternal-fetal circulation. Future studies, aimed at real-time visualization of the placental microvasculature and determination of the effect of ENM exposure on anatomical outcomes such as vascular density and structure, will be necessary to corroborate the present findings.

In conclusion, maternal ENM inhalation during gestation impairs fetoplacental vascular reactivity. Additionally, it appears that anatomic changes may also accompany this dysfunction. Because fetal outcomes were not reported in this study, the impacts of altered placental reactivity and anatomy on fetal health must be determined. It is equally important to determine the underlying mechanisms. We have initially identified endothelium-dependent and -independent effects herein, as well as an increased sensitivity to ANGII. However, future studies further explore mechanisms of reactivity such as pressure and shear-dependent vascular responses. Of equal importance is to fully define the scope and depth of alterations in the fetoplacental vascular anatomy after maternal ENM inhalation. Finally, the most sensitive periods during gestational development for these adverse outcomes that result from maternal inhalation expsoures should be determined.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure A. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure impairs endothelium-dependent placental hemodynamics. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure alters placental hemodynamics and decreases outflow (venous) pressure in placentas in normal superfusate (A) and placentas treated with ACh (B) (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.

Supplementary Figure B. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure does not affect endothelium-independent placental hemodynamics but increases ANGII sensitivity. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure did not affect endothelial-independent placental hemodynamics (A) but increased ANGII sensitivity (B) (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.

Supplementary Figure C. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation impairs calcium-free placental hemodynamics. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure alters placental hemodynamics and decreases outflow (venous) pressure in placentas in calcium-free superfusate (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.

Maternal gestational nano-TiO2 exposure increases placental vascular resistance.

Maternal gestational nano-TiO2 exposure is associated with a decreased placental endothelium-dependent response.

Placental and umbilical artery sensitivity to angiotensin II is increased by maternal nano-TiO2 exposure.

Umbilical artery and vein endothelium-dependent dilation is blunted by maternal nano-TiO2 exposure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin Engels from the WVU Department of Physiology and Pharmacology for his technical assistance in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the following sources: National Institutes of Health R01-ES015022 (TRN) and the National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement-1003907 (TRN, ABA).

Glossary

- ° C

Degrees Celsius

- μg

Micrograms

- μl

Microliters

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- ANGII

Angiotensin II

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- C

Mass concentration

- Ca2+-free

Calcium-free superfusate

- d

Diameter

- D

Deposition

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- Dcon

Control diameter

- Di

Internal diameter

- Dm

Maximal diameter

- Dss

Steady state diameter

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ELPI

Electrical low-pressure impactor

- ENM

Engineered nanomaterials

- F

Fractional deposition

- GD

Gestational day

- HEPA

High-efficiency particulate air

- HPAG

High-pressure acoustical generator

- ID

Internal diameter

- IUGR

Intrauterine growth restriction

- KeV

Kiloelectron volt

- M

Molar

- mM

Millimolar

- mm Hg

Millimeters of mercury

- mV

Millivolts

- N

Animal number

- n

Vessel number

- Nano-TiO2

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles

- NGS

Normal goat serum

- Nm

Nanometer

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PBSTX

Phosphate-buffered saline and Triton-X

- pDR

Personal dataram

- PE

Phenylephrine

- PSS

Physiological saline solution

- RAS

Renin-angiotensin system

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SMA

Smooth muscle actin

- SMPS

Scanning-mobility particle sizer

- SNAP

S-Nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine

- T

Exposure time

- TSA

Biotinylated tyramine

- V

Minute ventilation

- vWF

von Willerbrand factor

- WLR

Wall to lumen ratio

- WT

Wall thickness

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Abukabda AB, Stapleton PA, McBride CR, Yi J, Nurkiewicz TR, 2017. Heterogeneous Vascular Bed Responses to Pulmonary Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle Exposure. Front Cardiovasc Med 4,33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamcakova-Dodd A, Monick MM, Powers LS, Gibson-Corley KN, Thorne PS, 2015. Effects of prenatal inhalation exposure to copper nanoparticles on murine dams and offspring. Part Fibre Toxicol 12,30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ 2007. The origins of the developmental origins theory. Journal of internal medicine, 261(5), 412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum JL, Xiong JQ, Hoffman C, Zelikoff JT,2012. Cadmium associated with inhaled cadmium oxide nanoparticles impacts fetal and neonatal development and growth. Toxicol Sci. 126(2),478–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ema M, Hougaard KS, Kishimoto A, Honda K, 2016. Reproductive and developmental toxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials: A literature review. Nanotoxicology. 10(4),391–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Stapleton PA, Stalnaker JJ, Ren X, Hu H, Nurkiewicz TR, McBride CR, Yi J, Engels K, Simpkins JW,2016. Impacts of prenatal nanomaterial exposure on male adult Sprague-Dawley rat behavior and cognition. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 79(11),447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goeden N, Bonnin A, 2013. Ex vivo perfusion of mid-to-late-gestation mouse placenta for maternal-fetal interaction studies during pregnancy. Nat Protoc. 8(1),66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP,2001. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 38(3 Pt 2),718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafez S, 2017. Comparative Placental Anatomy: Divergent Structures Serving a Common Purpose. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 145, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong F, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Sheng L, Wang L, 2017. Maternal exposure to nanosized titanium dioxide suppresses embryonic development in mice. Int J Nanomedicine. 12,6197–6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang JP, Hsieh PC, Chen CY, Wang TY, Chen PC, Liu CC, Chen CC, Chen CP, 2015. Nanoparticles can cross mouse placenta and induce trophoblast apoptosis. Placenta. 36(12),1433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huppertz B, 2008. The anatomy of the normal placenta. J Clin Pathol. 61(12),1296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson HKL, Hansen JS, Elfving B, Lund SP, Kyjovska ZO, Loft S, Barfod KK, Jackson P, Vogel U, Hougaard KS, 2017. Airway exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes disrupts the female reproductive cycle without affecting pregnancy outcomes in mice. Part Fibre Toxicol. 14(1),17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krebs C, Macara LM, Leiser R, Bowman AW, Greer IA, Kingdom JC, 1996. Intrauterine growth restriction with absent end-diastolic flow velocity in the umbilical artery is associated with maldevelopment of the placental terminal villous tree. Am J Obstet Gynecol.175(6),1534–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Learmont JG,Poston L, 1996. Nitric oxide is involved in flow-induced dilation of isolated human small fetoplacental arteries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 174(2),583–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Li XH,Yuan H, 2012. Angiotensin II type-2 receptor-specific effects on the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2(1),56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandler WK, Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Kelley EE, Olfert IM, 2018. Microvascular Dysfunction Following Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Exposure Is Mediated by Thrombospondin-1 Receptor CD47. Toxicol Sci. 165(1),90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minarchick VC, Stapleton PA, Sabolsky EM, Nurkiewicz TR,2015. Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticle Exposure Improves Microvascular Dysfunction and Reduces Oxidative Stress in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Front Physiol 6,339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurkiewicz TR, Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Cumpston JL, Chen BT, Frazer DG, Castranova V,2008. Nanoparticle inhalation augments particle-dependent systemic microvascular dysfunction. Part Fibre Toxicol. 5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osol G,Mandala M, 2009. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology (Bethesda). 24,58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parivar K, Rudbari NH, Khanbabaee R, Khaleghi M, 2015. The Effect of Nano-Titanium Dioxide on Limb Bud Development of NMRI Mouse Embryo In Vivo. Cell J. 17(2),296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paull R, Wolfe J, Hébert P, Sinkula M, 2003. Investing in nanotechnology. Nat Biotechnol. 21(10),1144–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philbrook NA, Walker VK, Afrooz AN, Saleh NB, Winn LM, 2011. Investigating the effects of functionalized carbon nanotubes on reproduction and development in Drosophila melanogaster and CD-1 mice. Reprod Toxicol. 32(4), 442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rennie MY, Cahill LS, Adamson SL, Sled JG, 2017. Arterio-venous fetoplacental vascular geometry and hemodynamics in the mouse placenta. Placenta. 58, 46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah DM, 2005. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 288(4),F614–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stapleton PA, Nurkiewicz TR, 2014. Maternal nanomaterial exposure: a double threat to maternal uterine health and fetal development? Nanomedicine (Lond).9(7),929–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Yi J, Engels K, McBride CR, Nurkiewicz TR,2013. Maternal engineered nanomaterial exposure and fetal microvascular function: does the Barker hypothesis apply? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 209(3), 227 e1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stapleton PA, Hathaway QA, Nichols CE, Abukabda AB, Pinti MV, Shepherd DL, McBride CR, Yi J, Castranova VC, Hollander JM, Nurkiewicz TR, 2018. Maternal engineered nanomaterial inhalation during gestation alters the fetal transcriptome. Part Fibre Toxicol. 15(1),3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda-Matsubara Y, Iwai M, Cui TX, Shiuchi T, Liu HW, Okumura M, Ito M Horiuchi M,2004. Roles of angiotensin type 1 and 2 receptors in pregnancy-associated blood pressure change. American journal of hypertension, 17(8), 684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson LC, Urankar RN, Holland NA, Vidanapathirana AK, Pitzer JE, Han L, Sumner SJ, Lewin AH, Fennell TR, Lust RM, Brown JM,2014. C(6)(0) exposure augments cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury and coronary artery contraction in Sprague Dawley rats. Toxicol Sci. 138(2),365–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidanapathirana AK, Thompson LC, Mann EE, Odom JT, Holland NA, Sumner SJ, Han L, Lewin AH, Fennell TR, Brown JM, Wingard CJ,2014. PVP formulated fullerene (C60) increases Rho-kinase dependent vascular tissue contractility in pregnant Sprague Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol. 49,86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wick P, Malek A, Manser P, Meili D, Maeder-Althaus X, Diener L, Diener PA, Zisch A, Krug HF, von Mandach U 2010. Barrier capacity of human placenta for nanosized materials. Environ Health Perspect. 118(3), 432–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamashita K, Yoshioka Y, 2012. Safety assessment of nanomaterials in reproductive developmental field. Yakugaku Zasshi. 132(3),331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi J, Chen BT, Schwegler-Berry D, Frazer D, Castranova V, McBride C, Knuckles TL, Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Nurkiewicz TR,2013. Whole-body nanoparticle aerosol inhalation exposures. J Vis Exp.(75), e50263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure A. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure impairs endothelium-dependent placental hemodynamics. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure alters placental hemodynamics and decreases outflow (venous) pressure in placentas in normal superfusate (A) and placentas treated with ACh (B) (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.

Supplementary Figure B. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure does not affect endothelium-independent placental hemodynamics but increases ANGII sensitivity. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure did not affect endothelial-independent placental hemodynamics (A) but increased ANGII sensitivity (B) (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.

Supplementary Figure C. Maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation impairs calcium-free placental hemodynamics. Regression analysis showing that maternal nano-TiO2 inhalation exposure alters placental hemodynamics and decreases outflow (venous) pressure in placentas in calcium-free superfusate (n=8). *, P ≤ 0.05 sham-control group vs. nano-TiO2 exposed group.