Abstract

CYP1B1 is a member of the CYP1 subfamily of CYP superfamily of enzymes, which contains three members, CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1. CYP1B1 is expressed in both adult and fetal human extrahepatic tissues, including the parenchymal and stromal cells of most organs. Mutations in the CYP1B1 gene are linked to the development of primary congenital glaucoma in humans. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Using Cyp1b1-deficient mice, we showed that CYP1B1 is constitutively expressed in retinal vascular cells with a significant role in retinal neovascularization during oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy. We also showed CYP1B1 is constitutively expressed in trabecular meshwork (TM) cells and its expression plays a significant role in the normal development and function of the TM tissue. We have observed that germline deletion of Cyp1b1 is associated with increased oxidative stress in the retinal vascular and TM cells in culture, and retinal and TM tissue in vivo. We showed increased oxidative stress was responsible for altered production of the extracellular matrix proteins and had a significant impact on cellular integrity and function of these tissues. Collectively, our studies have established an important role for CYP1B1 expression in modulation of tissue integrity and function through the regulation of cellular redox homeostasis and extracellular microenvironment.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450, angiogenesis, oxidative stress, glaucoma, extracellular matrix Proteins, thrombospondin, periostin

1. Introduction

1.1. Cytochrome P450

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450s) belong to the super family of proteins that are heme containing monooxygenases [1]. Throughout the years, CYP450s have been extensively studied due to their involvement in oxidative metabolic activation and detoxification of many endogenous and exogenous compounds [1]. The majority of CYPs are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (microsomal fraction) of the liver. Liver contains the highest levels and greatest numbers and forms of CYPP450 enzymes among various tissues examined [2]. CYP450s metabolize many exogenous compounds including various drugs, and environmental chemicals and pollutants [3]. CYP450 metabolisms of foreign chemicals result in either successful detoxification or generation of toxic metabolites that contribute to increased risk of cancers and/or other toxic effects [4, 5]. The most common reaction catalyzed by CYPs is a mono-oxygenase reaction, which inserts one atom of oxygen into an organic substrate (RH) while another oxygen atom is reduced to water [6]: RH (Substrate) + O2 + NADPH + H+ → ROH (Product) + H2O + NADP+.

CYP450s could act on various endogenous substrates, introducing oxidative, peroxidative, and reductive changes into small molecules of widely different chemical structures [3]. Such substrates include saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, eicosanoids, sterols and steroids, bile acids, vitamin D3 derivatives, and retinoids [3, 4]. Cytochrome P450 enzymes have been identified in many species. There are nearly complete sets of CYP450 gene sequences for mouse, human, Anopheles gambiae (mosquitoe), Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode), Takifugu rubripes (puffer fish), Ciona intestinalis (sea squirt), Arabiodopsis thaliana (flowering plant), Oryza sativa (rice) and fungi [7]. The gene sequences of P450s identified in various species have extensive similarities, suggesting that the superfamily might have originated from a common ancestral gene approximately three billion years ago [8]. There are 57 and 102 putatively functional CYP450 genes in the human and mouse genome, respectively [7].

Recent advances in human genetic studies have identified mutations in several CYP450 genes whose dysfunction contribute to various pathological and developmental processes including cardiovascular diseases and glaucoma. The CYP450 enzymes identified within the vascular wall, include CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP2J2 and CYP2B6 [9]. In order to generate effective intracellular messengers, CYP450s interact with endogenous substrates such as retinoic acid, linoleic acid, and arachidonic acid, to generate intracellular messengers, such as cis-epoxyeicosatrienoic acids or mid-chain cis-trans-conjugated dienols with important roles in the modulation of angiogenesis, blood flow and vascular tone [10]. During development conserved expression and function of CYP orthologue in mice and humans have been demonstrated [11]. This is observed for CYP1B1, with mutations resulting in abnormal development of the conventional outflow pathway including the Schlemm’s canal and the trabecular meshwork in both mouse [12] and humans eyes [13], and is a major risk factor for congenital glaucoma [14].

In humans, CYP1B1 is expressed in many adult and fetal extrahepatic tissues including brain, kidney, prostate, breast, and ocular tissues. CYP1B1 is also expressed in neurovascular structures of the central nervous system including astrocytes [15]. Recent studies from our group demonstrated constitutive CYP1B1 expression in vascular cells, which plays a significant role during postnatal retinal vascular development and pathological neovascularization [16–19]. These studies have established a significant role for CYP1B1 expression in modulation of oxidative stress, sustained activation of NF-κB, and up-regulation of thrombospondin-2 (TSP2), in retinal vascular cells [16]. Thus, the expression of CYP1B1 in retinal vascular cells have a significant impact on angiogenesis. However, the role of CYP1B1 expression in retinal astrocytes, the other major cellular component of the retinal vasculature, remains largely unknown. In this review, we will discuss the physiological role of CYP1B1 expression in the trabecular meshwork and retinal vascular cell function including astrocytes, and how CYP1B1 expression in these cells may impact trabecular meshwork dysgenesis and retinal neovascularization.

2. Cytochrome p450 1B1 (CYP1B1)

2.1. CYP1 family

CYP1B1 is part of the CYP1 family of enzymes, which contains three members: CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1. Sequence analysis of CYP1B1 nucleic and amino acid sequences reveal a 40% homology to CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 [3]. CYP1B1 gene is located on chromosome 2p22–21 and consists of only three exons [20, 21]. Human CYP1B1 consists of three exons (371, 1044 and 3707 bp in length) and two introns (390 and 3032 bp) spanning 8.5 kbp of genomic DNA (GenBank accession no. U56438) [13, 20, 22]. Its coding region starts at the 5’-end of the second exon and ends with the last exon [20]. Conservatively, mouse Cyp1b1 gene located on chromosome 17 (MGI: 88590), also exhibits a structure with three exons and two introns. Its exon 1 is composed of 371 bp. The open reading frame (1630 bp) is encoded by exon 2 (starting at the second nucleotide; 1042 bp) and 16% of exon 3 (3780 bp). Introns 1 and 2 are composed of 376 bp and 2591 bp, respectively, [21].

2.2. CYP1B1 expression in humans

CYP1B1 is expressed in both adult and fetal human extrahepatic tissues, including most parenchymal and stromal tissues of brain, kidney, prostate, breast, cervix, uterus, ovary, lymph nodes [23], and ocular tissues [13, 24]. Strong immunoreactivity is localized in the neurons and astrocytes of the human brain cortex, in tubule cells of the kidney, secretory cells of the mammary gland, epithelial cells of the prostate, cervix and uterus, oocytes and follicular cells in the ovary, lymphoid cells and macrophages in lymph nodes, and stromal and muscle cells in uterus and cervix. However, it is barely detectable in the liver hepatocytes [1].

In general, fetal tissues expressed higher levels of CYP1B1 than adult tissues. CYP1B1 is detected in the fetal primitive ciliary epithelium as early as 26 days post-conception in human embryos. CYP1B1 staining in the corneal epithelium, keratocytes and iris stromal cells is positive in fetal but not in adult eyes [25]. This suggested that CYP1B1 plays an important role in normal fetal development. More recently, constitutive expression of CYP1B1 detected in human aortic vascular smooth muscles cells, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and human colonic epithelia [26–29].

2.3. CYP1B1 expression in mice

In mice, CYP1B1 exhibits a tissue specific pattern of expression [21]. During early murine embryonic development, Cyp1b1 mRNA was detected at embryonic day 9.5 in the eye, hindbrain, brachial arches, forelimb bud, ligaments supporting the primordial liver and the kidney [28]. Embryonic expression of Cyp1b1 at day 10.5 was restricted along the axis of development in the eye region, which will become the neural layer and the nasal half of the retina. In the forelimb bud, Cyp1b1 is localized posteriorly and no changes occurred in the hindbrain expression. At 11.5 days post-conception, changes in the polarity of Cyp1b1 expression is observed in the ventral portion of the neural retina, as well as expression around the optic eminence. However, Cyp1b1 expression is no longer detectable in the hind limb bud.

In an immunohistochemical study performed by Schenkman’s group, CYP1B1 was identified in the adult mouse eye and newborn (P0) whole microsomes, as well as localized to the ciliary and corneal epithelium, retinal inner nuclear cells, and ganglion cells. In the lens epithelium, CYP1B1 protein increased during development from embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) to postnatal day 7 (P7), after which its levels declined. CYP1B1 expression was almost undetectable in the inner ciliary epithelium before E17.5, but increased during postnatal development and peaked by P28. In both the corneal epithelium and the inner nuclear layer, CYP1B1 expression was highest in the adult animals. CYP1B1 expression slowly increased in the ganglion cell layer from E15.5 to P7 and then rapidly reached adult levels. This group, however, was unable to detect CYP1B1 expression in the trabecular meshwork (TM) during any stages of development or in the adult eye [28]. Very low levels of CYP1B1 have also been detected in normal adult kidney and uterus tissues [30]. However, no immunoreactivity was detected in the lung, liver, or brain, but could be observed, with the highest in lung tissue, after induction with α-napthoflavone [31].

More recently, we showed constitutive CYP1B1 expression in endothelial cells (EC) prepared from vascular beds of various tissues of 4-week old C57BL/6j mice, including retina, heart, lung, kidney, and liver [17]. We also showed constitutive expression of CYP1B1 in retinal pericytes (PC), as well as PC from heart and kidney [19]. 2,3,7,8-Tetracholordibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), or dioxin, was also used to induce CYP1B1 expression in these cells. Retinal, heart, and kidney PC showed upregulation of CYP1B1 expression after exposure to TCDD for 48 h. Other groups have shown CYP1B1 expression in mouse aortic vascular smooth muscle cells, as well as in normal colonic tissue [26]. In contrast to the studies indicating lack of CYP1B1 expression in the TM tissue during murine development, as well as in the adult, more recent studies from our group showed constitutive expression of CYP1B1 in TM cells. We also showed CYP1B1 expression plays an important role in normal development and function of the TM tissue [32]. Thus, the expression of Cyp1b1during prenatal development, and especially during the continuing postnatal development of the eye, may play important roles in guiding proper development and the overall function of these tissues.

2.4. CYP1B1 regulation

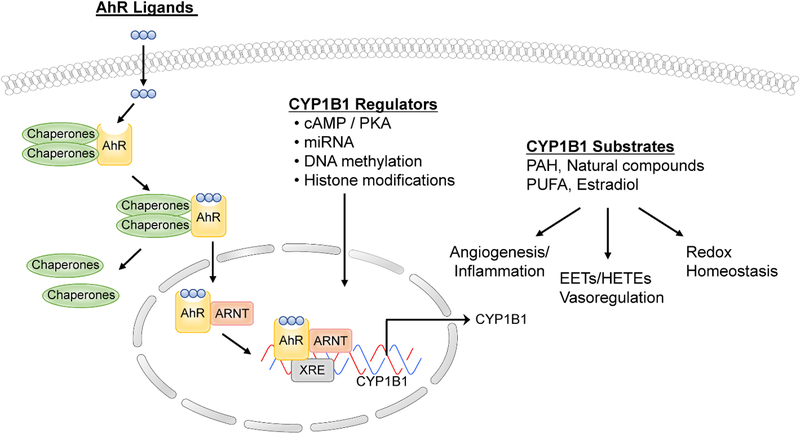

CYP1B1 is a key enzyme involved in the metabolism of exogenous and endogenous substrates, many of which include carcinogenic compounds. Many studies have demonstrated a role for CYP1B1 in the bioactivation of pro-carcinogens, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heterocyclic amines [33–35], which act via the AhR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor) complex. AhR is a ligand-activated basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and member of the basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim family of DNA binding regulatory proteins. AhR binds a widespread variety of exogenous compounds ranging from plant flavonoids to toxic environmental pollutants such as PAHs. In normal resting cells, AhR is bound to several co-chaperones, including p23, HSP90, and XAp2/ARA9 in the cytosol. Upon ligand binding, such as TCDD, the chaperones dissociate resulting in AhR translocating into the nucleus and dimerization with its partner AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) [36–41]. The AhR/ARNT heterodimer subsequently binds to the xenobiotic-response element (XRE) using the basic helix-loop-helix motifs located within the amino terminal of the AhR and ARNT and modulates the expression of various genes including CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regulation of CYP1B1 expression, metabolic activity, and biological functions.

In mice and rats, Cyp1b1 not only exhibits AhR-regulated expression, but is also regulated by 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) mediated pathways [21, 42]. Steroidogenic transcription factor-1 motifs associated with cAMP-dependent transcriptional activation of genes are present in the 5′ upstream regulatory sequences of the mouse Cyp1b1 gene [42]. CYP1B1 is constitutively expressed in steroidogenic tissues. In these tissues, primarily hormones that typically regulate cAMP levels govern regulation of CYP1B1. CYP1B1 metabolizes 17β-estradiol to generate several metabolites, among which 2- and 4-OH estradiol accounts for 75–80% of the products [43]. Other studies have shown that CYP1B1 expression is induced by 17β-estradiol in estrogen receptor (ER) positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which is mediated by direct interaction of ER-α with estrogen response element (ERE) in the CYP1B1 promoter region [44].

Inducible expression of CYP1B1 may also involve non-AhR-mediated mechanisms. For example in Ahr null mice, Cyp1b1 but not Cyp1a1, mRNA is weakly inducible in liver by piperonyl butoxide [45]. However, other studies showed no induction of a Cyp1b1 promoter construct by dioxin when the construct was transiently transfected into Ahr-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts [21]. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, CYP1B1 is an unstable protein in the absence of a substrate (benzanthracene). Thus, protein stabilization by a substrate may also contribute to the regulation of Cyp1b1 activity [46].

Our transcriptional understanding of the precise mechanisms involved in the regulation of CYP1B1 expression is far from complete. As with other methods of regulation, epigenetic modifications could play a significant role in the transcriptional regulation of Cyp1b1. Two of the most important modifications include covalent chromatin/histone modifications and DNA methylation. Covalent chromatin modifications function either by altering the nucleosomal architecture and/or by affecting the recruitment of non-histone proteins to chromatin [47, 48]. DNA methylation suppresses gene expression directly by interfering with the binding of transcription factors that recruit histone deacetylases to generate an inactive heterochromatin structure [49]. CpG islands have been identified in the enhancer and promoter regions of the human CYP1B1 gene and alterations in DNA methylation are noted in various types of cancers [50, 51]. For example, a study demonstrated that the CYP1B1 gene is silenced in HepG2 cells by hypermethylation of its promoter. Treatment of these cells with 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine led to partial demethylation of the promoter, restored RNA polymerase II and TATA binding protein (TBP) binding, and thus, CYP1B1 inducibility [52]. Another study showed CYP genes were regulated by inhibition of DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) during the differentiation of hepatocytes from human embryonic stem cells [53]. Further studies are required to improve our understanding of the expression and activity of CYP enzymes by epigenetic regulation.

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression through translational repression or mRNA cleavage [54]. Within the human genome, the total number of miRNAs is predicted to be as high as 1,000 and control up to 20 – 30% of genes [55]. Recently, attention is focused on the expression profiles of miRNAs in various types of human tumors, and miRNAs may be one of the key regulators of tumorigenesis. CYP1B1 protein is abundant in many cancers. Tsuchiya et al identified a near-perfect matching sequence with miR-27b in the 3’-untranslated region of human CYP1B1 [56]. Their studies suggested that human CYP1B1 is post-transcriptionally regulated by miR-27b. They evaluated breast cancer patients and demonstrated that in tissues with high levels of CYP1B1 protein, miR-27b levels were decreased. Thus, this decreased expression of miR-27b may be one of the causes of high CYP1B1 protein expression in cancerous tissues. Another study showed that in renal cell cancer (RCC), CYP1B1 is post-transcriptionally regulated by miR-200c, and thus, high CYP1B1 protein expression and enzyme activity may be caused by low expression of miR-200c in RCC. They also showed that CYP1B1 up-regulation is not related to tumorigenicity unlike other studies. Interestingly, these studies found that miR-200c-mediated CYP1B1 regulation is involved in the chemosensitiviy of RCC to docetaxel [57].

Our studies have established an important role for oxygen levels in regulation of Cyp1b1 activity and likely its expression. We observed increased adverse effects in the absence of Cyp1b1 when cells or animals were subjected to ambient oxygen or high oxygen levels, respectively. In contrast, the adverse effects of Cyp1b1-deficiency were minimal under lower oxygen levels as occurs during embryonic development (<10%). Capillary morphogenesis of Cyp1b1−/− EC was restored under hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen) [16]. How changes in oxygen levels contribute to regulation of Cyp1b1 expression and/or activity needs further exploration.

3. CYP1B1 function

3.1. CYP1B1 and neurovascular function

CYP1B1 mediates the metabolism of endogenous substrates such as dietary plant flavonoids, the hydroxylation of melatonin, the formation of genotoxic catechol estrogens and retinoic acid with significant impact on developmental and tissue homeostasis processes [58–60]. However, little is known about how the activity of CYP1B1 impacts specific cellular functions. CYP1B1 expression occurs in neurovascular structures of the central nervous system including AC [15]. In addition, AC under inflammatory and/or oxidative conditions express higher levels of CYP1B1, which is relieved using the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) [61]. Furthermore, recent studies have linked altered expression of CYP1B1 to development and progression of AC/glial tumors [62]. However, very little is known about the cell autonomous activity of CYP1B1 in AC and its dysfunction in neurovascular defects associated with diabetes and other neurological disorders associated with exposure to various environmental pollutants and toxicants.

Using Cyp1b1-deficient mice, our laboratory recently showed that Cyp1b1 is constitutively expressed in retinal vasculature and retinal vascular cells, and plays a significant role in retinal neovascularization during oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy (OIR) [16–19]. Although we have demonstrated the cell autonomous impact of Cyp1b1-deficiency in retinal EC and PC (discussed below), we know little about the physiological role of Cyp1b1 expression in AC, the other major cellular component of the retinal neurovasculature.

Astrocytes are the most abundant cells in the central nervous system [63]. Their functions range from secretion or absorption of neural transmitters to maintenance of the blood-brain and blood-retina barrier. Astrocyte dysfunction could contribute to various pathologies including diabetic retinopathy and various neurological disorders. Our interest in retinal AC comes from its critical role during normal inner retinal vascularization and degeneration of retinal AC in ischemic tissues with damage to the blood retinal barrier in ischemia-mediated neovascularization [64]. In fact, AC are the major source of the matricellular proteins thrombospondins-1 and-2 (TSP1 and TSP2) that have significant roles in retinal neuronal synaptogenesis [65], as well as regulation of angiogenesis [66]. Our recent studies have further expanded our knowledge about the molecular and cellular mechanisms acting through Cyp1b1 and contribute to retinal neurovascular development and angiogenesis, and likely its neuronal function.

Mechanistically, we showed that germline deletion of Cyp1b1 is associated with increased oxidative stress in the retinal EC and PC in culture, and retinal tissue in vivo. We also showed increased oxidative stress in the retinal vascular cells was responsible for increased production of TSP2, an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, and attenuation of retinal neovascularization [16, 17]. This was, however, rescued by the use of antioxidant NAC establishing an important role for redox changes associated with Cyp1b1 deficiency [16]. In addition, knockdown of TSP2 was sufficient to restore the proangiogenic activity of retinal vascular cells. Astrocytes play a key role in maintaining the neuroretina function, and production of TSPs by AC play a significant role in neurogenesis and modulation of angiogenesis [65]. However, the role AC CYP1B1 expression plays in the retinal vascular development and function remain unknown.

3.2. Retinal vascular development

The retinal vascular network has an important role in supplying the inner portion of the retina with oxygen and nutrients during development [67]. In humans, the retina begins to vascularize around 16 weeks of gestational age. During the early stages, nutrients and oxygen to the eye is provided by the hyaloid vasculature originating from the optic nerve and traversing the primitive vitreous toward the anterior segment [68]. The hyaloid vasculature must regress when ocular development proceeds in order to attain a transparent visual axis [69]. Hyaloid regression is completed before 34 weeks of gestation. The nasal retina becomes fully vascularized at 36 weeks of gestation, and the temporal vessels reach the ora serrata at approximately 40 weeks. Humans are born with fully developed retinal vessels and a regressed hyaloid vasculature. Unlike humans, mouse are born without a retinal vasculature, and retinal vasculature develops postnatally by angiogenesis [68].

Retinal vascular development is controlled by interactions between ganglion cells (GC), AC, EC, and PC [67]. Before vascular sprouting from the optic nerve head, AC migrate from the optic nerve head toward the periphery and form a fine scaffolding that guides the extension of EC and PC. Ganglion cells secrete platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A) to stimulate AC proliferation. Astrocytes in turn secrete VEGF-A, which stimulates leading endothelial tip cells to produce long filopodium along the astrocytic template, which serves as a means for sensing the immediate environment [70, 71]. This leads to formation of a superficial layer of retinal vasculature by first week of postnatal life. These vessels then sprout deep into the retina during second and third postnatal week of life forming the deep and intermediate layer of the retinal vasculature. Retinal Muller cells and inner neurons drive and control these processes. The primary retinal vascular plexus is completed by three weeks of life and continues remodeling and pruning, completing retinal vascularization by six weeks of age [67, 72].

3.3. Retinal vascular development and neovascularization in Cyp1b1−/− mice

We observed relatively normal postnatal retinal vascularization in Cyp1b1−/− mice without a significant effect on retinal vascular density and, EC, PC, and AC numbers. However, retinal neovascularization was attenuated when Cyp1b1−/− mice were subjected to OIR. OIR is a highly reproducible model of pathological angiogenesis in vivo [73]. Cyp1b1−/− mice were subjected to a cycle of hyperoxia and normoxia, but were unable to elicit a neovascular response. Thus, suggesting that Cyp1b1 expression plays an important role during hyperoxia-mediated ischemic neovascularization in the retina. We demonstrated this is mainly attributed to the increased oxidative stress in the absence of Cyp1b1, which results in sustained activation of NF-κB and up-regulation of the endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis TSP2. We also showed that retinal EC prepared from Cyp1b1+/+ mice constitutively express CYP1B1, which is further induced by AhR agonist, TCDD [16]. Retinal EC prepared from Cyp1b1−/− mice were less migratory, less adhesive and failed to undergo capillary morphogenesis in Matrigel; consistent with our observations during OIR in which the Cyp1b1−/− mice failed to undergo retinal neovascularization. We also observed significant attenuation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and nitric oxide (NO) production in the Cyp1b1−/− EC. Inhibition of eNOS in wild type EC resulted in attenuation of capillary morphogenesis similar to the Cyp1b1−/− EC. Additionally, restoration of eNOS expression in Cyp1b1−/− EC or their incubation with a NO donor was sufficient to improve their migration and capillary morphogenesis [17]. Furthermore, we showed that loss of Cyp1b1 was associated with increased oxidative stress and increased TSP2 expression in retinal EC [16].

Retinal PC also constitutively express CYP1B1, and it was induced by TCDD [74]. Cyp1b1−/− PC exhibited increased oxidative stress and TSP2 production. Administration of anti-oxidant NAC reduced oxidative stress and TSP2 expression, both in vivo and in cultured vascular cells in vitro [75, 76]. In summary, we showed that CYP1B1 is constitutively expressed in the EC and PC of mouse retina, and that its absence had a dramatic impact on angiogenesis in vivo and proangiogenic activities of vascular cells in culture, likely through modulation of redox homeostasis.

Despite the abundant amount of information generated regarding the function of CYP1B1 in the vasculature and vascular cells, many questions still remain. Astrocytes are obligatory constituents of the central nervous system vasculature and play integral roles in maintaining vascular homeostasis, as well as are key players during pathological events. However, very few studies exemplify their importance in the neurovascular function. We have recently focused on delineating the role Cyp1b1 expression plays in retinal AC function, and further investigated the cell autonomous impact of Cyp1b1 expression during retinal vascular development and neovascularization using a transgenic mice with Cyp1b1 allele floxed. Our preliminary studies demonstrated that targeted deletion of Cyp1b1 in PC, using a Pdgfrb-Cre line of transgenic mice, is sufficient to protect against retinal neovascularization during OIR (Our unpublished data). This is consistent with our cell culture studies where we found retinal PC as major CYP1B1 and TSP2 expressers. We know little about the expression of CYP1B1 in retinal AC and its impact on retinal vascular function.

3.4. Astrocytes and retinal vasculature

Astrocytes provide a variety of supportive functions to neurons in the CNS, such as neuronal guidance during development, and nutritional, metabolic support to neurons, maintenance of the blood–brain and blood-retina barrier and secretion or absorption of neural transmitters [71]. Impairment of normal AC functions during brain ischemia, stroke and others insults can influence neuronal survival. Recovery after a brain injury is influenced by AC surface molecule expression and trophic factor release [77]. Apart from various neuropathological conditions, AC play a particularly important role in retinal vascular development, and disease such as glaucoma [67, 78–80]. Expression of glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) has become a marker for identification of AC and its up-regulation in response to stress.

In the retina, three basic types of glial cells are found. These include the Muller and astroglial cells (refer to as macroglia) and microglial cells (refer to as microglia). These cell types are important for retinal function and have a wide range of indispensable activities for neuronal survival and vascular function. They maintain ionic equilibrium, regulate neuronal metabolism and participate in the blood-retina barrier as well as being involved in some retinal pathologies [81–85]. In particular, AC play an important role in the development of the mammalian retinal vasculature and ischemia-mediated neovascularization [67].

Retinal AC are not glial cells of the retinal neuroepithelium but enter the developing retina from the brain along the developing optic nerve laying down the scaffolding essential for retinal vascularization [86]. Astrocytes closely associate with the developing retinal vasculature with significant impact on retinal vessels function [82]. In animals with only partially vascularized retinas, such as rabbit and horse, no retinal AC is found in the avascular regions of the retina [87–89]. Thus, the presence of AC is important during retinal neurovascular development and function.

Retinal AC develop from an astrocyte precursor lineage moving in to the retina from the optic nerve head (ONH) as a mixture of precursor cells and immature perinatal AC. They then extend through the nerve fiber layer towards the retinal peripheral margins. The precursor cells undergo three stages of differentiation. Stage one, is defined by immature AC expressing GFAP, Pax2 and vimentin. The mature AC then arise by the loss of vimentin expression but retain GFAP, Pax2 and S100B expression. At the final stage, adult AC show a robust expression of GFAP, PDGF-Rα and S100β [90]. The migration of AC is closely regulated by the PDGF-Rα ligand, PDGF-A, secreted by retinal GC. Cells expressing PDGF-Rα at the ONH don’t migrate toward the retina until PDGF-A is detected in GC [91]. Inhibition of PDGF signaling results in significant, but incomplete, inhibition of the AC migration and network formation [64]. However, when PDGF-A is overexpress in GC it causes AC to migrate slower forming a denser astrocytic network [64, 92]. The mechanisms surrounding this delay in migration and hyperplasia of AC remains unknown. One possibility is that too much PDGF signaling results in a more mature AC lineage with decreased motility [90].

The retina provides essential extracellular matrix for AC migration. Studies have shown that AC from rat brain migrate towards laminin in microchemotaxis assays, which can be inhibited by administrating laminin-specific pentapeptide, YIGSR-NH2 [93]. Genetic deletion of the laminin chains α1, β2, γ3 also disrupts AC migration, increase microglial cell recruitment to the hyperbranched vascular plexus, and influence EC proliferation [94–96]. One explanation is that laminins act as a haptotactic factor in vitro in an isoform-specific manner, inducing AC migration and promoting their differentiation [95].

During their migration to the periphery, AC serve as a template for EC and PC to follow, thereby guiding the formation of the superficial vascular network, which in turn promotes AC differentiation [97, 98]. Endothelial cells produce leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), which stimulate AC differentiation in vitro [99–104]. Deletion of LIF receptor in mice results in failure of generating AC expressing GFAP [105]. LIF in cooperation with BMP2, induces AC differentiation by increasing GFAP activation [106]. However, LIF-deficient mice show a more subtle phenotype compared to the LIF receptor mutants [107] Thsu, indicating that additional cytokines might be involve in AC differentiation [90]. In vitro studies have shown that AC progenitor cells can be stimulated by ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) [103] and FGF2 [108], while stage one AC responds to EGF [109, 110]. However, the in vivo role of these factors awaits confirmation.

Retinal AC are involved in a variety of developmental and pathological conditions. Studies using mammalian eyes are excellent models for the studies of AC in CNS because retina shares a common origin with brain. Visualization of AC provides unique advantages for studying interaction among neurons, glial cells and vessels [111], and because of AC confinement and proximity to the optic nerve, the interaction of nerve fiber layer of the inner retina and retinal vasculature. Studies have shown that changes in the brain vasculature during diseases can be reflected in retinal vascular changes [112, 113], suggesting that studies of retinal AC could attribute to a better understanding of development and pathologies of glial cells in the CNS.

One of the most studied functions of AC is the establishment of the astrocytic network for retinal angiogenesis [114]. Astrocytes are found in richly vascularized retinas. In support of this idea, overexpression of PDGF-A results in an increase in retinal vasculature that is proportional to the AC hypertrophy [64]. Others have shown, that the loss of GC layer is accompanied by the reduced AC density and attenuation of retinal vascularization in anencephalic human fetuses [115]. However, others studies have shown that mice deficient in Brn3b [116] or Math5 [117], where retinal GC are mostly depleted, showed that the retina was completely devoid of vascular plexus, persistent hyaloid vessels, and their astrocytic networks were retained in contrast to what was previously reported.

In addition to the formation of the retina vasculature, AC along with Muller cells, are important for maintaining the blood-retina-barrier [85, 118, 119]. In cyclic hyperoxia, depletion of the AC population precedes depletion of superficial retinal vessels and neovascularization [115]. Alterations in AC reactivity have been linked to blood-retina-barrier breakdown in retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) [83, 120] and diabetic retinopathy [121, 122]. Protecting retinal AC from degeneration is thus an important venue of research in ROP [123].

The energy requirements of the retina are very high, and tight regulatory mechanisms operate to ensure adequate supply. This is clinically important, because most retinal diseases such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy among others including retinal ischemia [124–126], where metabolite are limited and energy supply is decreased. Within the retina, the complex metabolic relationships between glial cells and neurons undergo different processes that soothe their metabolic activity according to their needs. For example, Muller cells can resist hypoxia and low glucose environment due to their ability to activate anaerobic glycolysis or by oxidizing alternative substrates such as lactate and glutamine in order to obtain energy [127–130].

In the brain, AC provide neurons with essential metabolites such as glucose, and they take up K+ and neurotransmitters from the extracellular space. However, studies have shown that AC have the capacity to fully oxidize glucose and/or lactate [131] despite the fact that they present a high glycolytic rate [132–134].They are responsible for the replenishment of brain glutamate, as they are the only neural cell type expressing pyruvate carboxylase, a key enzyme that allows the synthesis of glutamate from glucose [135]. Astrocytes convert glucose to lactate and then release the lactate to be taken up and oxidized by neurons. They are responsible for the glycogen mobilization within the brain since glycogen stored exclusively in AC [136]. Overall AC play an important and active role in complex brain physiological functions.

We know little about the metabolic activities of AC in the retina. We showed exposure of retinal AC to high glucose conditions results in increased cell proliferation and adhesion to ECM proteins, and attenuation of network formation on Matrigel. This were associated with increased levels of αvβ3 integrin, as well as the activation of MAPK/ERKs and JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathways [137]. High glucose conditions promoted the AC expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα, as well as iNOS. Thus, high glucose conditions alter AC function by increased production of inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress with significant impact on their proliferation, adhesion, and migration. Our recent characterization of retinal AC from Cyp1b1−/− mice also indicates an important role for CYP1B1 expression in modulation of adhesive, migratory, and inflammatory characteristics. We have observed enhanced proliferation, increased adhesion, reduced migration, and decreased production of inflammatory mediators with minimal effects on MAPK and AKT signaling pathways. Cyp1b1−/− AC are also more tolerant of oxidative stress, perhaps because of increased CD38 and connexin 43 expression (our unpublished data). However, the detailed mechanisms of CYP1B1 action in retinal AC require further investigation.

4. CYP1B1 and pathophysiology

4.1. Primary congenital glaucoma

Glaucoma is currently the leading cause of blindness worldwide with no known cure. It is a type of optic neuropathy leading to progressive damage of the optic nerve and visual field that can further result in loss of vision if left untreated [138]. Types of glaucoma are categorized according to the etiology, anatomy of the anterior chamber, and the time of onset [139]. Among these, primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) is the most common form of pediatric glaucoma [140] and accounts for up to 18% of childhood blindness [141, 142], whose incidence varies geographically [143]. In detail, PCG mainly presents with developmental defects of the trabecular meshwork (TM) and/or Schlemm’s canal [14]. The trabecular meshwork is a porous tissue located around the base of the cornea near the ciliary body whose role is to maintain homeostasis of the intraocular pressure (IOP) by draining the aqueous humor from the anterior chamber, into the Schlemm’s canal, and drainage through the lymphatic vein [144]. Abnormalities in the TM and/or Schlemm’s canal causes an obstruction of the aqueous outflow leading to increase intraocular pressure (IOP) in PCG patients. The elevation of IOP leads to the death of retinal GC and optic nerve damage, and finally loss of vision if left untreated [145].

Molecular screening have revealed that the majority of PCG cases present with CYP1B1 mutations within the GLC3A locus on chromosome 2p21 [13]. CYP1B1 is critical in the proper development of TM (the most important tissue in regards to PCG) [146, 147] and also in the in utero development of others ocular tissues [25]. Strong expression of CYP1B1 in eyes suggested an important role for CYP1B1 in normal eye development and function in mice and humans [11, 25, 148]. Cyp1b1-deficient mice exhibit small or absent Schlemm’s canal, fibers in the TM, and attachments of the iris to the TM [32]. However, the mechanism by which CYP1B1 leads to proper TM development remains under investigation. Our studies established an important role for TM CYP1B1 expression in modulation of oxidative stress and the ECM protein periostin. Decreased levels of periostin produced by Cyp1b1-deficient TM cells resulted in degeneration of TM tissue, as also demonstrated in the Periostin deficient mice [149].

4.2. Cyp1B1 and cancer

Cytochrome P450s account for approximately 75% of enzymes involved in xenobiotic metabolism. Although metabolism of foreign chemicals frequently results in successful detoxification, these enzymes can also generate toxic/genotoxic metabolites that contribute to increased risks of cancer, birth defects, and other effects [4, 150]. Many studies have demonstrated a role for CYP1B1 in the bioactivation of pro-carcinogens, such as PAHs and heterocyclic amines.

In general, CYP1B1 levels are usually low in normal adult tissues [151–153]. However, overexpression of CYP1B1 is observed in a wide variety of tumors, particularly from hormone-responsive tissues, such as prostate, breast, endometrial, and ovarian, but also in colon, lung, renal, and bladder [151, 154–156]. The CYP1 family is involved in hydroxylation of two major biologically active estrogens in non-pregnant women, estradiol and estrone. Estradiol is the strongest estrogen produced by ovaries; estrone has a weaker activity and is the major estrogenic form found in menopausal women [157, 158]. CYP1B1 converts estradiol or estrone into 4-hydroxyestradiol (4-OHE2) or 4-hydroxyestrone (4-OHE1) [159, 160]. This product, if not eliminated through conjugation, can be oxidized to produce estradiol-3,4-semiquinone and estrogen-3,4-quinone. The quinone product reacts with purines in DNA to form depurinating adducts, which potentially gives rise to DNA mutations. More importantly, the 4-OHE2 and the semiquinones/quinones can undergo redox cycling [157, 161].

CYP1B1 has been implicated in the progression of cancer by altering the tissue response to hormones and anticancer agents [162]. CYP1B1 mRNA and protein have both been detected in normal prostate tissue and prostate tumors, however, the levels of CYP1B1 are markedly higher in prostate cancer compared to benign tissues [151, 163]. Polymorphisms of CYP1B1 have been characterized in different cancers [164–166]. The four most common polymorphisms of the CYP1B1 gene have been reported to result in amino acid substitutions these include: Leu432Val, Asn453Ser, Arg48Gly, and Ala119Ser. Numerous epidemiological studies have been carried out to evaluate the association between CYP1B1 polymorphisms and different types of cancer risk [167]. However, the results from these studies were inconsistent or contradictory. In summary, CYP1B1, through the bio-activation of pro-carcinogen and endogenous metabolism by sex steroid hormones, contributes to carcinogenesis and cancer of many organs.

4.3. Cyp1b1 and cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death globally: more people die annually from CVDs than from any other causes. It is well known that CYPs are expressed within the cardiovascular system and play critical roles in the regulation of various cellular and physiological processes [10, 168–171]. CYP-derived eicosanoids have numerous effects toward physiological and pathophysiological events within the body, which depends on the type, quantity and timing of metabolites produced. Alterations in fatty acid composition and concentrations have a role in CVD. The metabolism of n-3 and n-6 PUFA into a plethora of bioactive eicosanoids occurs through three primary enzymatic systems including cyclooxygenases (COX), lipoxygenases (LOX) and cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes [172]. There is a growing understanding of the relative contribution of CYP-derived eicosanoids toward cardiac function and dysfunction suggesting the importance of these metabolites. Arachidonic acid (AA) is a polyunsaturated fatty acid that is present in the phospholipids of all cell membranes. CYP2C and CYP2J readily metabolize AA via epoxidation to four epoxyeicosantrienoic acid (EET) regioisomers (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, 14,15-EET) [170]. EETs are further converted to more stable and less active metabolites, dihydroxyeixosatrienoic acids (DHETs) [173].

The hydroxyl-metabolites of AA are divided into mid-chain and ω/ω−1 hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) [174]. CYP1B1, and to a lower extent CYP1As, have lipoxygenase-like activity of oxidizing AA to mid-chain HETEs, typified by 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE, through hydroperoxy-intermediates [60, 175]. CYP1B1 is highly expressed in VSMC and to a lesser degree in EC [16, 176], but shear stress upregulates the mRNA and protein levels of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in EC [29]. Whether CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 contribute to the vascular function is not well established. However, a heterogeneous group of CYP catalyzes the formation of terminal HETEs, most importantly, CYP1As for 16-, 17, 18- and 19-HETE [177], CYP2E1 and CYP4A2 for 19-HETE [174, 178], and CYP4As and CYP4Fs for 20-HETE [179]. The effects of CYP-derived AA metabolites on cardiovascular system are multifaceted. For example, EETs exhibit potent vasodilatory, anti-platelet, anti-inflammatory, fibrinolytic, vascular smooth muscle anti-migratory, and angiogenic properties [173, 180, 181]. In contrast, 20-HETE is reported to be a potent vasoconstrictor [182] and pro-inflammatory [183], and it stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell migration [184]. Further elucidation of their role in both physiological and pathophysiological states will provide novel therapeutic strategies to improve cardiovascular health.

5. Cyp1b1 and oxidative stress

Oxidative stress generally becomes evident when the generation of reactive oxygen species over comes the intracellular anti-oxidant capacity. There are many sources, which contribute to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and several pathways that work to remove the threat from these highly reactive compounds. Given the nature of CYP enzymes where oxygen is an important component for their reaction activity, it is possible that lack of these enzymes may lead to increase oxygen availability and ROS production, especially under hyperoxic conditions. We showed EC lacking Cyp1b1 fail to undergo capillary morphogenesis under ambient oxygen conditions (20% oxygen) and exhibit increased oxidative stress. We found that the attention of capillary morphogenesis could be reversed by incubating Cyp1b1−/− EC under hypoxic (1% oxygen) conditions, or by administration of NAC [16]. Furthermore, NAC administration was sufficient to restore retinal neovascularization and protect degeneration of TM tissue in Cyp1b1−/− mice [16, 32]. However, the source responsible for production of ROS in the absence of Cyp1b1 remains unknown.

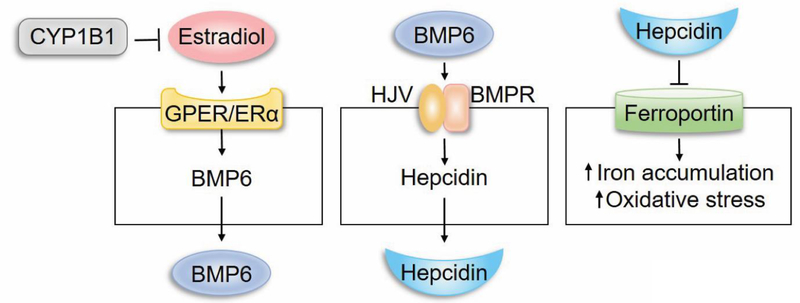

We previously showed minimal contribution from common sources involved in ROS production including mitochondria, NADPH-oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and non-enzymatic oxidized products of PUFA [16]. Recent metabolic studies have also established an important role for Cyp1b1 in fatty acid oxidation and obesity [185]. Gene expression profiling of liver from wild type and Cyp1b1−/− mice identified hepcidin as a significantly downregulated gene in absence of Cyp1b1. In the liver hepcidin is produced by hepatocyte in response to changes in iron level and increased production of bone morphogenic protein 6 (BMP-6) by sinusoidal EC [186, 187]. Hepcidin is an important iron regulatory hormone whose expression along with hemojuvelin enhance the ubiquitination and degradation of ferroportin, the main iron transporter, attenuating iron export and cause increased intracellular iron accumulation [186]. Increased levels of iron can produce superoxides, which react with peroxide radical released from PUFA generating high reactive lipid peroxide such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and oxidative stress [188].

Our recent studies demonstrated decreased production of BMP-6 in sinusoidal EC prepared from Cyp1b1−/− mice [189]. Thus, it is possible that decreased levels of BMP6 in sinusoidal EC may decrease hepcidin production by hepatocytes and increase iron export through ferroportin resulting in higher systemic iron levels (Figure 2). The increased iron level may enhance intracellular iron uptake and production of lipid peroxides increasing oxidative stress. One of the key question that remains is whether the BMP6/hepcidin/ferroportin axis contributes to the pathogenesis of congenital glaucoma and attenuation of ischemia-mediated retinal neovascularization. Given the fact that the eye has all regulatory components of iron homeostasis [190], it remains to be determine how these regulatory pathways are altered with Cyp1b1 deficiency, and whether alterations in intracellular iron levels contribute to these pathologies.

Figure 2.

CYP1B1 regulation of intracellular iron levels through BMP6 signaling and hepcidin production, and regulation of redox homeostasis.

6. Concluding remarks

CYP1B1 and perhaps other CYP family members which utilize oxygen for their metabolic activity play an important role in mainiaing cellular and tissue redox homeostasis. Mutations that inactivates the enzymatic activity of these genes could lead to increased oxidative stress, especially under ambient oxygen conditions. We have found that global deletion of Cyp1b1 resulted in increased oxidative stress in retinal vascular cells and tissue attenuating neovascularization under hyperoxic conditions. In addition, lack of Cyp1b1 resulted in increased oxidative stress in TM tissue and TM cells, and degeneration of TM tissue. Similar abnormalities are also observed in the liver and liver sinusoidal EC suggesting an important role for iron homeostasis exacerbating the production of ROS and oxidative stress and tissue damage. Thus, understanding the signaling pathways that contribute to increased oxidative stress with Cyp1b1-deficiency will advance our understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to pathogenesis of congenital glaucoma in humans with CYP1B1 deficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an unrestricted award from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Retina Research Foundation, P30 EY016665, P30 CA014520, EPA 83573701, EY022883, and EY026078. CMS is supported by the RRF/Daniel M. Albert Chair. NS is a recipient of RPB Stein Innovation Award.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muskhelishvili L et al. (2001) In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analysis of cytochrome P450 1B1 expression in human normal tissues. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society 49 (2), 229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimada T, G.E., Sutter TR, Strickland PT, Guengerich FP, Yamazaki H (1997) Oxidation of xenobiotics by recombinant human cytochrome P450 1B1. Drug Metab Dispos 25, 617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DR et al. (1996) P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics 6 (1), 1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nebert DW and Russell DW (2002) Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet 360 (9340), 1155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimada T et al. (1996) Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P-450 1B1. Cancer Res 56 (13), 2979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter TD and Coon MJ (1991) Cytochrome P-450. Multiplicity of isoforms, substrates, and catalytic and regulatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem 266 (21), 13469–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson DR et al. (2004) Comparison of cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes from the mouse and human genomes, including nomenclature recommendations for genes, pseudogenes and alternative-splice variants. Pharmacogenetics 14 (1), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nebert DW and Gonzalez FJ (1987) P450 Genes: Structure, Evolution, and Regulation. Annual Review of Biochemistry 56 (1), 945–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coon MJ (2005) CYTOCHROME P450: Nature’s Most Versatile Biological Catalyst. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 45 (1), 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming I, Vascular Cytochrome P450 Enzymes: Physiology and Pathophysiology, 2008, pp. 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Choudhary D et al. (2006) Physiological Significance and Expression of P450s in the Developing Eye. Drug Metabolism Reviews 38 (1–2), 337–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libby RT et al. (2003) Modification of ocular defects in mouse developmental glaucoma models by tyrosinase. Science (New York, N.Y.) 299 (5612), 1578–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoilov I et al. (1997) Identification of three different truncating mutations in cytochrome P4501B1 (CYP1B1) as the principal cause of primary congenital glaucoma (Buphthalmos) in families linked to the GLC3A locus on chromosome 2p21. Hum Mol Genet 6 (4), 641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasiliou V and Gonzalez FJ (2008) Role of CYP1B1 in glaucoma. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48, 333–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieder CR et al. (1998) Cytochrome P450 1B1 mRNA in the human central nervous system. Mol Pathol 51 (3), 138–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Y et al. (2009) CYP1B1 expression promotes the proangiogenic phenotype of endothelium through decreased intracellular oxidative stress and thrombospondin-2 expression. Blood 113 (3), 744–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Y et al. (2010) CYP1B1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase combine to sustain proangiogenic functions of endothelial cells under hyperoxic stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298 (3), C665–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palenski TL et al. (2013) Cyp1B1 expression promotes angiogenesis by suppressing NF-κB activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305 (11), C1170–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palenski TL et al. (2013) Lack of Cyp1b1 promotes the proliferative and migratory phenotype of perivascular supporting cells. Lab Invest 93 (6), 646–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang YM et al. (1996) Isolation and characterization of the human cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 gene. J Biol Chem 271 (45), 28324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L et al. (1998) Characterization of the mouse Cyp1B1 gene. Identification of an enhancer region that directs aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated constitutive and induced expression. J Biol Chem 273 (9), 5174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray GI et al. (2001) Regulation, function, and tissue-specific expression of cytochrome P450 CYP1B1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41, 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muskhelishvili L Kusewitt Df, W.C.K.F.F.T.P.A. (2001) In situ hybridization and monotheistic analysis of cytochrome P450 1B1 expression in human normal tissues. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry. official journal of the Histochemistry Society 49, 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoilov I et al. (1998) Sequence analysis and homology modeling suggest that primary congenital glaucoma on 2p21 results from mutations disrupting either the hinge region or the conserved core structures of cytochrome P4501B1. Am J Hum Genet 62 (3), 573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doshi M et al. (2006) Immunolocalization of CYP1B1 in normal, human, fetal and adult eyes. Exp Eye Res 82 (1), 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerzee JK and Ramos KS (2001) Constitutive and inducible expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of the Ahr bHLH/PAS transcription factor. Circ Res 89 (7), 573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson P et al. (2003) Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) is overexpressed in human colon adenocarcinomas relative to normal colon: implications for drug development. Mol Cancer Ther 2 (6), 527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary D et al. (2007) Cyp1b1 protein in the mouse eye during development: an immunohistochemical study. Drug Metab Dispos 35 (6), 987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conway DE et al. (2009) Expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in human endothelial cells: regulation by fluid shear stress. Cardiovasc Res 81 (4), 669–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattacharyya KK et al. (1995) Identification of a rat adrenal cytochrome P450 active in polycyclic hydrocarbon metabolism as rat CYP1B1. Demonstration of a unique tissue-specific pattern of hormonal and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-linked regulation. J Biol Chem 270 (19), 11595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savas U et al. (1994) Mouse cytochrome P-450EF, representative of a new 1B subfamily of cytochrome P-450s. Cloning, sequence determination, and tissue expression. J Biol Chem 269 (21), 14905–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y et al. (2013) Cyp1b1 mediates periostin regulation of trabecular meshwork development by suppression of oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol 33 (21), 4225–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otto S et al. (1992) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism in rat adrenal, ovary, and testis microsomes is catalyzed by the same novel cytochrome P450 (P450RAP). Endocrinology 131 (6), 3067–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pottenger LH and Jefcoate CR (1990) Characterization of a novel cytochrome P450 from the transformable cell line, C3H/10T1/2. Carcinogenesis 11 (2), 321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada T and Fujii-Kuriyama Y (2004) Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carcinogens by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1. Cancer Sci 95 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perdew GH (1988) Association of the Ah receptor with the 90-kDa heat shock protein. J Biol Chem 263 (27), 13802–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okey AB et al. (1980) Temperature-dependent cytosol-to-nucleus translocation of the Ah receptor for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in continuous cell culture lines. Journal of Biological Chemistry 255 (23), 11415–11422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denison MS et al. (1986) Ah receptor for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Codistribution of unoccupied receptor with cytosolic marker enzymes during fractionation of mouse liver, rat liver and cultured Hepa-1c1 cells. Eur J Biochem 155 (2), 223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis M et al. (1988) Association of the dioxin receptor with the Mr 90,000 heat shock protein: a structural kinship with the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 155 (2), 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuthill S et al. (1987) The receptor for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in the mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa 1c1c7. A comparison with the glucocorticoid receptor and the mouse and rat hepatic dioxin receptors. J Biol Chem 262 (8), 3477–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuchiya Y et al. (2003) Critical enhancer region to which AhR/ARNT and Sp1 bind in the human CYP1B1 gene. J Biochem 133 (5), 583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brake PB and Jefcoate CR (1995) Regulation of cytochrome P4501B1 in cultured rat adrenocortical cells by cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate and 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Endocrinology 136 (11), 5034–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuchiya Y et al. (2004) Human CYP1B1 Is Regulated by Estradiol via Estrogen Receptor. Cancer Research 64 (9), 3119–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christou M et al. (1994) Co-expression of human CYP1A1 and a human analog of cytochrome P450-EF in response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachloro-dibenzo-p-dioxin in the human mammary carcinoma-derived MCF-7 cells. Carcinogenesis 15 (4), 725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryu DY et al. (1996) Piperonyl butoxide and acenaphthylene induce cytochrome P450 1A2 and 1B1 mRNA in aromatic hydrocarbon-responsive receptor knock-out mouse liver. Mol Pharmacol 50 (3), 443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savas U and Jefcoate CR (1994) Dual Regulation of Cytochrome-P450ef Expression Via the Aryl-Hydrocarbon Receptor and Protein Stabilization in C3h/10t1/2 Cells. Mol Pharmacol 45 (6), 1153–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kouzarides T (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 (4), 693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B et al. (2007) The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128 (4), 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo Y et al. (2002) Regulation of DNA methylation in human breast cancer. Effect on the urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene production and tumor invasion. J Biol Chem 277 (44), 41571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tokizane T et al. (2005) Cytochrome P450 1B1 is overexpressed and regulated by hypomethylation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11 (16), 5793–5801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Habano W et al. (2009) CYP1B1, but not CYP1A1, is downregulated by promoter methylation in colorectal cancers. Int J Oncol 34 (4), 1085–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beedanagari SR et al. (2010) Role of epigenetic mechanisms in differential regulation of the dioxin-inducible human CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 genes. Molecular pharmacology 78 (4), 608–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park HJ et al. (2015) Differences in the Epigenetic Regulation of Cytochrome P450 Genes between Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Hepatocytes and Primary Hepatocytes. Plos One 10 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ambros V (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431 (7006), 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berezikov E et al. (2005) Phylogenetic Shadowing and Computational Identification of Human microRNA Genes. Cell 120 (1), 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsuchiya Y et al. (2006) MicroRNA regulates the expression of human cytochrome P450 1B1. Cancer Research 66 (18), 9090–9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang I et al. (2015) Loss of miR-200c up-regulates CYP1B1 and confers docetaxel resistance in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 6 (10), 7774–7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brake PB et al. (1999) Developmental expression and regulation of adrenocortical cytochrome P4501B1 in the rat. Endocrinology 140 (4), 1672–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buters JT et al. (1999) Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 determines susceptibility to 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced lymphomas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (5), 1977–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choudhary D et al. (2004) Metabolism of retinoids and arachidonic acid by human and mouse cytochrome P4501B1. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 32 (8), 840–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayo L et al. (2014) Regulation of astrocyte activation by glycolipids drives chronic CNS inflammation. Nat Med 20 (10), 1147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett JA et al. (2007) Cytochrome P450 1B1 expression in glial cell tumors: an immunotherapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res 13 (12), 3559–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malaplate-Armand C et al. (2003) Astroglial CYP1B1 up-regulation in inflammatory/oxidative toxic conditions: IL-1beta effect and protection by N-acetylcysteine. Toxicol Lett 138 (3), 243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fruttiger M et al. (1996) PDGF mediates a neuron-astrocyte interaction in the developing retina. Neuron 17 (6), 1117–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christopherson KS et al. (2005) Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell 120 (3), 421–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Farnoodian M et al. (2017) Negative regulators of angiogenesis: important targets for treatment of exudative AMD. Clin Sci (Lond) 131 (15), 1763–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fruttiger M (2007) Development of the retinal vasculature. Angiogenesis 10 (2), 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stahl A et al. (2010) The Mouse Retina as an Angiogenesis Model. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 51 (6), 2813–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell CA et al. (1998) Regression of vessels in the tunica vasculosa lentis is initiated by coordinated endothelial apoptosis: A role for vascular endothelial growth factor as a survival factor for endothelium. Developmental Dynamics 213 (3), 322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheef E et al. (2005) Isolation and characterization of murine retinal astrocytes. Mol Vis 11, 613–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sofroniew MV and Vinters HV (2010) Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 119 (1), 7–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang S et al. (2003) Thrombospondin-1-deficient mice exhibit increased vascular density during retinal vascular development and are less sensitive to hyperoxia-mediated vessel obliteration. Dev Dyn 228 (4), 630–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith LE et al. (1994) Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 35 (1), 101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palenski TL et al. (2013) Lack of Cyp1b1 promotes the proliferative and migratory phenotype of perivascular supporting cells. Lab Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palenski TL et al. (2013) Cyp1B1 expression promotes angiogenesis by suppressing NF-kappaB activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305 (11), C1170–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lawler J (2000) The functions of thrombospondin-1 and-2. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12 (5), 634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen Y and Swanson RA (2003) Astrocytes and Brain Injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23 (2), 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coorey NJ et al. (2012) The role of glia in retinal vascular disease. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 95 (3), 266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin ES et al. (2014) Diabetes and retinal vascular dysfunction. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 9 (3), 362–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schneider M and Fuchshofer R (2016) The role of astrocytes in optic nerve head fibrosis in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 142, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bay V and Butt AM (2012) Relationship between glial potassium regulation and axon excitability: A role for glial Kir4.1 channels. Glia 60 (4), 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meeks JP and Mennerick S (2007) Astrocyte membrane responses and potassium accumulation during neuronal activity. Hippocampus 17 (11), 1100–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan-Ling T and Stone J (1992) Degeneration of astrocytes in feline retinopathy of prematurity causes failure of the blood-retinal barrier. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 33 (7), 2148–2159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yao H et al. (2014) The development of blood-retinal barrier during the interaction of astrocytes with vascular wall cells. Neural regeneration research 9 (10), 1047–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tout S et al. (1993) The role of Müller cells in the formation of the blood-retinal barrier. Neuroscience 55 (1), 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Watanabe T and Raff MC (1988) Retinal astrocytes are immigrants from the optic nerve. Nature 332 (6167), 834–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schnitzer J (1987) Retinal astrocytes: their restriction to vascularized parts of the mammalian retina. Neurosci Lett 78 (1), 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stone J and Dreher Z (1987) Relationship between astrocytes, ganglion cells and vasculature of the retina. Journal of Comparative Neurology 255 (1), 35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schnitzer J (1988) Astrocytes in the guinea pig, horse, and monkey retina: Their occurrence coincides with the presence of blood vessels. Glia 1 (1), 74–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tao CQ and Zhang X (2014) Development of Astrocytes in the Vertebrate Eye. Developmental Dynamics 243 (12), 1501–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mudhar HS et al. (1993) PDGF and its receptors in the developing rodent retina and optic nerve. Development (Cambridge, England) 118 (2), 539–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reneker LW and Overbeek PA (1996) Lens-specific expression of PDGF-A in transgenic mice results in retinal astrocytic hamartomas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37 (12), 2455–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Armstrong RC et al. (1990) Type 1 astrocytes and oligodendrocyte-type 2 astrocyte glial progenitors migrate toward distinct molecules. J Neurosci Res 27 (3), 400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Edwards MM et al. (2010) Mutations in Lama1 Disrupt Retinal Vascular Development and Inner Limiting Membrane Formation. J Biol Chem 285 (10), 7697–7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gnanaguru G et al. (2013) Laminins containing the 2 and 3 chains regulate astrocyte migration and angiogenesis in the retina. Development 140 (9), 2050–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Biswas S et al. (2017) Laminin-Dependent Interaction between Astrocytes and Microglia. The American Journal of Pathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gerhardt H et al. (2003) VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. The Journal of Cell Biology 161 (6), 1163–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dorrell MI et al. (2002) Retinal vascular development is mediated by endothelial filopodia, a preexisting astrocytic template and specific R-cadherin adhesion. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 43 (11), 3500–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoshida T et al. (1993) Cytokines affecting survival and differentiation of an astrocyte progenitor cell line. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 76 (1), 147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakagaito Y et al. (1995) Effects of leukemia inhibitory factor on the differentiation of astrocyte progenitor cells from embryonic mouse cerebral hemispheres. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 87 (2), 220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Richards LJ et al. (1996) Leukaemia inhibitory factor or related factors promote the differentiation of neuronal and astrocytic precursors within the developing murine spinal cord. The European journal of neuroscience 8 (2), 291–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bonni A et al. (1997) Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science (New York, N.Y.) 278 (5337), 477–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mi H and Barres BA (1999) Purification and Characterization of Astrocyte Precursor Cells in the Developing Rat Optic Nerve. The Journal of Neuroscience 19 (3), 1049 LP–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Galli R et al. (2000) Regulation of neuronal differentiation in human CNS stem cell progeny by leukemia inhibitory factor. Dev Neurosci 22 (1–2), 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koblar SA et al. (1998) Neural precursor differentiation into astrocytes requires signaling through the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (6), 3178–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nakashima K et al. (1999) Astrocyte differentiation mediated by LIF in cooperation with BMP2. FEBS Lett 457 (1), 43–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kubota Y et al. (2008) Leukemia inhibitory factor regulates microvessel density by modulating oxygen-dependent VEGF expression in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 118 (7), 2393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lin G and Goldman JE (2009) An FGF-responsive astrocyte precursor isolated from the neonatal forebrain. Glia 57 (6), 592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Raff MC et al. (1983) Two types of astrocytes in cultures of developing rat white matter: differences in morphology, surface gangliosides, and growth characteristics. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 3 (6), 1289–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Spina Purrello V et al. (2002) Effect of growth factors on nuclear and mitochondrial ADP-ribosylation processes during astroglial cell development and aging in culture. Mech Ageing Dev 123 (5), 511–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chan-Ling T, Glial, neuronal and vascular interactions in the mammalian retina, 1994, pp. 357–389.

- 112.Mitchell P et al. (2005) Retinal microvascular signs and risk of stroke and stroke mortality. Neurology 65 (7), 1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Patton N et al. (2005) Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: a rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J Anat 206 (4), 319–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gariano RF (2003) Cellular mechanisms in retinal vascular development. Prog Retin Eye Res 22 (3), 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kim JH et al. (2010) Impaired retinal vascular development in anencephalic human fetus. Histochem Cell Biol 134 (3), 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sapieha P et al. (2008) The succinate receptor GPR91 in neurons has a major role in retinal angiogenesis. Nature Medicine 14 (10), 1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Edwards MM et al. (2012) The deletion of Math5 disrupts retinal blood vessel and glial development in mice. Experimental Eye Research 96 (1), 147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Holländer H et al. (1991) Structure of the macroglia of the retina: Sharing and division of labour between astrocytes and Müller cells. J Comp Neurol 313 (4), 587–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gardner TW et al. (1997) Astrocytes increase barrier properties and ZO-1 expression in retinal vascular endothelial cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 38 (11), 2423–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stone J et al. (1996) Roles of vascular endothelial growth factor and astrocyte degeneration in the genesis of retinopathy of prematurity. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 37 (2), 290–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rungger-Brändle E et al. (2000) Glial reactivity, an early feature of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41 (7), 1971–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ly A et al. (2011) Early Inner Retinal Astrocyte Dysfunction during Diabetes and Development of Hypoxia, Retinal Stress, and Neuronal Functional Loss. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 52 (13), 9316–9316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dorrell MI et al. (2010) Maintaining retinal astrocytes normalizes revascularization and prevents vascular pathology associated with oxygen-induced retinopathy. Glia 58 (1), 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kaur C et al. (2008) Hypoxia-ischemia and retinal ganglion cell damage. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Osborne NN et al. (2004) Retinal ischemia: Mechanisms of damage and potential therapeutic strategies. Prog Retin Eye Res. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schmidt KG et al. (2008) Neurodegenerative Diseases of the Retina and Potential for Protection and Recovery. Current Neuropharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kitano S et al. (1996) Hypoxic and excitotoxic damage to cultured rat retinal ganglion cells. Exp Eye Res 63 (1), 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Reichenbach A and Bringmann A (2010) Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 129.Stone J et al. , Mechanisms of photoreceptor death and survival in mammalian retina, 1999, pp. 689–735. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Winkler BS et al. (2000) Energy metabolism in human retinal Müller cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41 (10), 3183–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zielke HR et al. , Direct measurement of oxidative metabolism in the living brain by microdialysis: A review, pp. 24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Itoh Y et al. (2003) Dichloroacetate effects on glucose and lactate oxidation by neurons and astroglia in vitro and on glucose utilization by brain in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100 (8), 4879–4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Herrero-Mendez A et al. (2009) The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C–Cdh1. Nature Cell Biology 11 (6), 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bittner CX et al. (2010) High resolution measurement of the glycolytic rate. Frontiers in Neuroenergetics 2, 26–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bélanger M et al. (2011) Brain Energy Metabolism: Focus on Astrocyte-Neuron Metabolic Cooperation. Cell Metabolism 14 (6), 724–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Magistretti PJ and Allaman I, A Cellular Perspective on Brain Energy Metabolism and Functional Imaging, 2015, pp. 883–901. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 137.Shin ES et al. (2014) High glucose alters retinal astrocytes phenotype through increased production of inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. PLoS One 9 (7), e103148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Quigley HA and Broman AT (2006) The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 90 (3), 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Coleman AL and Brigatti L (2001) The glaucomas. Minerva Med 92 (5), 365–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Taylor RH et al. (1999) The epidemiology of pediatric glaucoma: the Toronto experience. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 3 (5), 308–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gilbert CE et al. (1994) Causes of blindness and severe visual impairment in children in Chile. Dev Med Child Neurol 36 (4), 326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tabbara KF and Badr IA (1985) Changing pattern of childhood blindness in Saudi Arabia. The British journal of ophthalmology 69 (4), 312–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lewis CJ et al. (2017) Primary congenital and developmental glaucomas. Human Molecular Genetics 28, 621–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tamm ER (2009) The trabecular meshwork outflow pathways: Structural and functional aspects. Experimental Eye Research 88 (4), 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Khan Kareem A et al. (2015) Prolonged elevation of intraocular pressure results in retinal ganglion cell loss and abnormal retinal function in mice. Exp Eye Res 130, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Stoilov I, Cytochrome P450s: Coupling development and environment, 2001, pp. 629–632. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Stoilov I et al. (2001) Roles of cytochrome p450 in development. Drug Metabol Drug Interact 18 (1), 33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]