ABSTRACT

Influenza vaccination is an important public health intervention for older adults, yet vaccination rates remain suboptimal. We conducted an online survey of Canadians ≥ 65 years to explore satisfaction with publicly-funded standard-dose influenza vaccines, and perceptions of the need for a more effective product. They were provided with information about currently approved influenza vaccines, and were asked about their preferences should all formulations be available for free, and should the recently approved high-dose (HD) vaccine for seniors be available at a cost. From March to April 2017, 5014 seniors completed the survey; mean age was 71.3 ± 5.17 years, 50% were female, and 42.6% had one or more chronic conditions. 3403 (67.9%) had been vaccinated against influenza in the 2016/17 season. Of all respondents, 3460 (69%) were satisfied with the standard-dose influenza vaccines, yet 3067 (61.1%) thought that a more effective vaccine was/may be needed. If HD was only available at a cost, 1426 (28.4%) respondents would consider it, of whom 62.9% would pay $20 or less. If all vaccines were free next season, 1914 (38.2%) would opt for HD (including 12.2% of those who previously rejected influenza vaccines), 856 (17.1%) would choose adjuvanted vaccine, and 558 (11.1%) standard-dose vaccine. 843 (16.8%) of respondents were against vaccines, 451 (9.0%) had no preference and 392 (7.8%) were uncertain. Making this product available through publicly funded programs may be a strategy to increase immunization rates in this population.

Keywords: Influenza, Vaccines, decision-making, Survey, willingness-to-pay, seniors

Introduction

Influenza is highly prevalent, and can be severe.1 While the majority of those afflicted will recover within 10 days, adults 65 years and over are at increased risk for more serious outcomes such as exacerbation of underlying medical conditions or complications such as pneumonia and cerebrovascular events.2 Hospitalization can have lasting impact on older adults’ functional status; about one third of older adults are discharged from hospital with persistent declines in functions compared with their pre-admission status.3 Catastrophic disability, defined as new dependence in two or more basic Activities of Daily Living, has been found to affect 15% of older Canadians who are discharged from hospital following a bout of influenza.4,5 Given that influenza has serious implications for older adults over both short and long time horizons, prevention is a key strategy to support healthy aging.

In Canada, each province and territory is responsible for its own vaccine funding decisions, as well as public health messaging and promotion.6 Given that the influenza vaccine that an individual will receive is dependent on various factors (which vaccine(s) their province has purchased, whether they reside in a long-term care facility or in the community, which vaccine(s) is available at the setting where they opt to receive the vaccine, etc.), the provincial health messaging is focused on influenza prevention, rather than vaccine formulations. Prior to 2015, three influenza vaccine formulations had been approved for use in Canada: standard-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV), standard-dose adjuvanted TIV, and standard-dose quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (QIV). Standard-dose TIV is publicly funded in all provinces, while QIV and adjuvanted TIV are funded in several. Despite this, vaccine uptake in seniors is typically within 64–67%, far lower than the national goal of 80%.7,8 This is likely at least partially due to low public confidence in the benefits of the influenza vaccine, especially given messaging that it may have lower efficacy in older adults.9-13 Results of previous national surveys corroborate this hypothesis and suggest that older adults are not certain about the severity of influenza or the effectiveness of influenza vaccines; the primary reasons given for opting against influenza vaccination include feeling that it is ineffective and unnecessary.14-16

In September 2015, a new high-dose (HD) influenza vaccine was approved for use in Canada for adults aged 65 years and over. HD vaccine contains four times the antigen of standard-dose influenza vaccines.17 It has been found to decrease the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza by 24% in this age group compared to the standard-dose vaccine.18 However, HD vaccine is not uniformly available or covered by public immunization programs in all jurisdictions. The opinions of Canadian seniors on whether they are adequately protected by the current publicly funded standard-dose vaccines, as well as the need for and value of a more effective vaccine have not yet been studied. As part of a larger survey of Canadian seniors to understand perceptions and self-reported severity of influenza,19 we gauged attitudes and behaviours towards influenza and influenza vaccines.

Results

Between March 20th and April 5th, 2017, completed surveys were collected from 5,014 adults 65 years and over, living in Canada. The mean age of the respondents was 71.3 ± 5.2 years (range = 65–96), 50.0% were female, and 42.6% had one or more chronic conditions (Table 1). Respondents represented all 10 Canadian provinces (territories were not included). The overall response rate was 30.4% and the median time to complete the survey was 14 minutes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents (n = 5014).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean age (yrs); SD | 71.34; 5.17 |

| Median age | 70 |

| 65 – 74 years | 3803 (75.8) |

| ≥ 75 years | 1211 (24.2) |

| Gender | |

| Man | 2507 (50.0) |

| Woman | 2505 (50.0) |

| Other (i.e. transgender) | 2 (0.0) |

| Province | |

| British Columbia | 711 (14.2) |

| Alberta | 435 (8.7) |

| Saskatchewan | 144 (2.9) |

| Manitoba | 166 (3.3) |

| Ontario | 1914 (38.2) |

| Quebec | 1258 (25.1) |

| New Brunswick | 124 (2.5) |

| Nova Scotia | 154 (3.1) |

| Prince Edward Island | 23 (0.5) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 85 (1.7) |

| Location | |

| Village (< 1,000 people) | 417 (8.3) |

| Town (1,000 to 99,999 people) | 1749 (34.9) |

| City (> 100,000 people) | 2848 (56.8) |

| Language | |

| English | 3600 (71.8) |

| French | 1414 (28.2) |

| Chronic condition | |

| None | 2877 (57.4) |

| Diabetes | 906 (18.1) |

| Heart disease | 551 (11.0) |

| Asthma or chronic lung disease other than COPD | 411 (8.2) |

| Blood disorders (not including high or low blood pressure) | 326 (6.5) |

| COPD | 260 (5.2) |

| Cancer | 220 (4.4) |

| Neurological disorders | 130 (2.6) |

| Kidney disease | 122 (2.4) |

| Significant trouble with memory | 83 (1.7) |

| Liver disease | 36 (0.7) |

| HIV/AIDS | 6 (0.1) |

This table summarizes respondents’ demographics, medical history and frailty and function levels at the time of survey completion

Vaccination behaviour

Of all respondents, the majority (3207, 64.0%) routinely received the influenza vaccine annually while 949 (18.9%) never received it, and the remaining did not adhere to a consistent pattern: 335 (6.7%) got it most years, 124 (2.5%) got it half the time, and 399 (8.0%) did not usually get it.

During the 2016/17 season, 3403 (67.9%) of respondents were vaccinated against influenza. For the 1578 respondents who reported that they did not receive the influenza vaccine, the most popular reasons for abstaining were not thinking that it was necessary (39.2%), not thinking it was effective (26.9%), concern about side-effects (22.9%), and disliking injections (13.3%).

Satisfaction with vaccines

Of all respondents, 3460 (69.0%) were satisfied with the publicly funded standard-dose vaccines, while 305 (6.1%) indicated that they were dissatisfied, and the remainder had neutral feelings. Despite this high level of satisfaction, 3067 (61.1%) felt that a more effective vaccines was/may be necessary. Additionally, when provided with the PHAC statement regarding the severity of influenza in the senior population, 22% of those who had previously responded that either a new influenza vaccine might be necessary or that they were unsure now indicated that the statement had led them to believe that a new vaccine was needed. Additionally, 12% of those who previously felt that the current vaccine was effective switched their response to “I now think a more effective vaccine is needed.” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in perceptions of need for new influenza vaccine*.

| Change in perception after reading PHAC statement |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I don’t know if a new vaccine is needed | I now think a more effective vaccine is needed | No change in my response | Other | ||

| Original response to question about whether a more effective vaccine is needed | I don’t know if a more effective vaccine is needed | 265 (24.6) |

311 (28.8) |

465 (43.1) |

38 (3.5) |

| I don’t believe in flu vaccines | 30 (6.2) |

26 (5.4) |

407 (84.3) |

20 (4.1) |

|

| Maybe a more effective vaccine is needed | 47 (2.5) |

552 (29.9) |

1226 (66.4) |

21 (1.1) |

|

| No, the current vaccine is effective | 46 (3.1) |

175 (12.0) |

1224 (83.6) |

19 (1.3) |

|

| Yes, a more effective vaccine is needed | 4 (2.8) |

135 (95.1) |

3 (2.1) |

||

*Dark grey shading indicates a change from the original response

When the responses of those who had influenza or ILI during the 2016/17 season were compared with those who did not, we found that those who had experienced illness were significantly less likely to report that the current vaccine was already effective and a new one was not needed (22.1% vs. 31.2%, p = 0.006).

Vaccine preferences

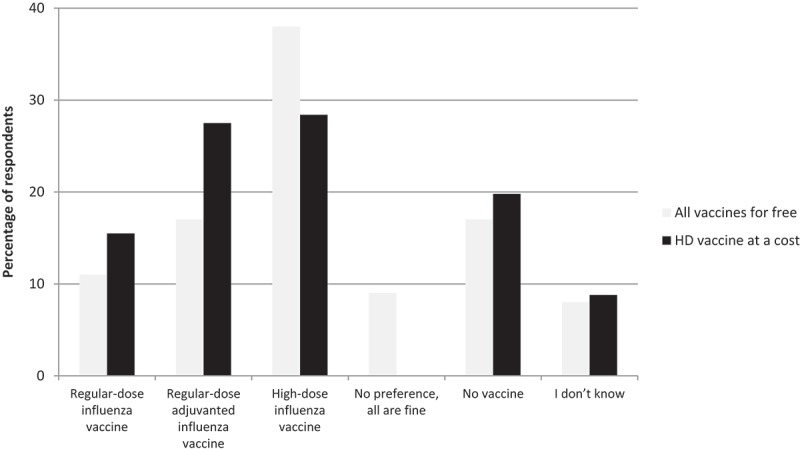

When asked about vaccine preferences for next influenza season, HD influenza vaccine was most commonly opted for (38.2%), while 17.1% would choose standard-dose adjuvanted, and 11.1% standard-dose (Figure 1). The remaining responses indicated equal affinity for all three vaccines (9.8%), being against influenza vaccine (16.8%) or uncertainty (7.8%). However, if HD vaccine was only available at a cost, the percentage of respondents who would opt for it would decrease to 28.4%.

Figure 1.

Influenza vaccine preferences.

In a sub-analysis of the 1,472 respondents who rarely or never receive the influenza vaccine, we found that if HD vaccine was available for free, 165 (12.2%) in this group would opt for it. Additionally, 59 (4.4%) indicated that they would choose to receive standard-dose vaccine and 82 (6.1%) would choose adjuvanted vaccine. If HD was available but only at a cost, we observed that a higher percentage of respondents who reported having influenza or ILI in the 2016/17 season would opt for it, compared to those who had not been ill (32.9% vs. 27.0%, p = 0.03).

When all respondents were asked how they would feel if a more effective influenza vaccine was publicly funded in other provinces but not their own, 59.8% indicated that they would be bothered.

Willingness to pay for influenza vaccine

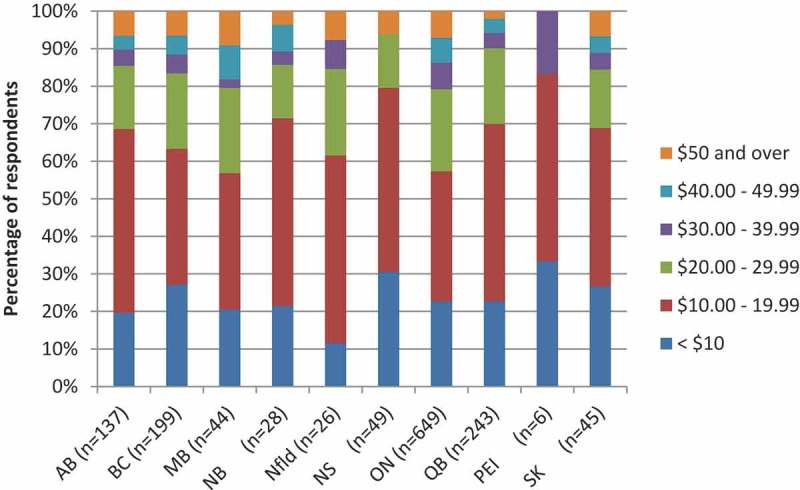

Of the 1426 respondents who would receive HD vaccine even if they incurred a cost, willingness to pay varied: 6.0% would be willing to pay $50 CDN or more, 5.3% ($40.00–49.99), 5.5% ($30–39.99), 20.2% ($20.00–29.99), 39.8% ($10.00–10.99), and 23.1% would pay up to $10.

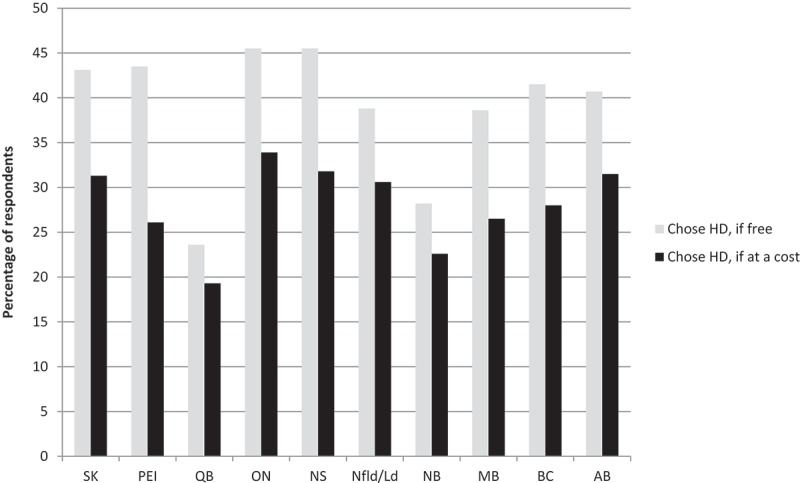

Respondents from Quebec and New Brunswick were least likely to opt for HD if it was available for free than those from other provinces (23.6% and 28.2%, respectively; Figure 2). If HD was only available at a cost, there were observed declines in those opting for HD across all provinces. The actual cost that respondents were willing to pay for the vaccine also varied by province – those who were willing to pay for HD in Manitoba, Ontario and Newfoundland indicated that they would be receptive to paying more than those in other provinces (43.2%, 42.7% and 38.5% would pay over $20, respectively, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Influenza vaccine choice, by province (n = 5014).

Figure 3.

Willingness to pay for HD vaccine, by province (n = 1426).

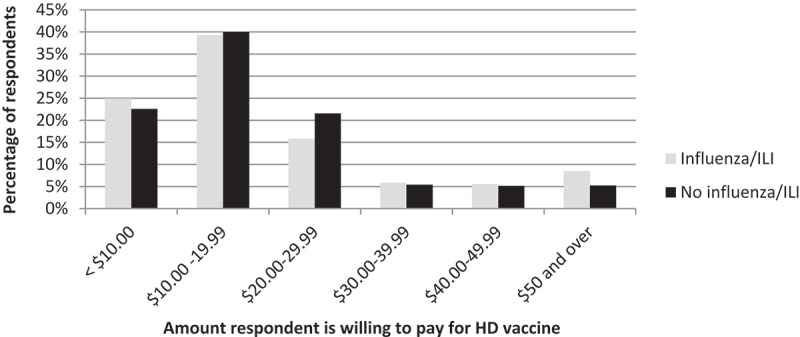

Of those who responded that they would be willing to pay for HD vaccine depending on the cost, 8.5% of those who reported having influenza/ILI in the 2016/17 season indicated that they would pay $50 or more, compared to 5.3% of those who had not been ill (Figure 4, p = 0.3).

Figure 4.

Willingness to pay for HD vaccine, by influenza/ILI status in the 2016/17 season.

Perceived priorities when decision-making

Respondents were asked about what their provincial governments should prioritize when considering whether or not to publicly fund an influenza vaccine, and the most common responses were vaccine effectiveness (78.5%), vaccine safety (47.7%), severity of influenza in this population (38.1%), and NACI recommendations (34.7%). Vaccine cost and seniors’ satisfaction with currently available vaccines were not prioritized as strongly (27.1% and 13.1%, respectively). Twelve individuals who chose “other” priority specified that the cost of treating influenza in the senior population (including hospitalization) should also be factored into the decision-making process.

Respondent factors associated with influenza vaccine-related opinions and behaviors

Being 75 years and older, having at least one chronic conditions, and being satisfied with the current influenza vaccine were factors significantly associated with receiving the influenza vaccine regularly (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of patient factors with opinions, perceptions and behaviors.

| |

Typically receive influenza vaccine |

Satisfied with current influenza vaccine |

Perceive need for new influenza vaccine |

Opt for HD vaccine if available for free |

Opt for HD vaccine if available at a cost |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.42 (1.13, 1.79) | 0.003 | 1.63 (1.40, 1.90) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.79, 1.03) | 0.13 | 0.80 [0.69, 0.92) | 0.002 | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) | 0.62 |

| Female | 0.84 (0.69, 1.01) | 0.07 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.91) | 0.00046 | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) | 0.06 | 0.83 (0.74, 0.94) | 0.004 | 0.72 (0.64, 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Location Town City |

1.13 (0.79, 1.60) 1.23 (0.88, 1.73) |

0.51 0.23 |

1.07 (0.85, 1.34) 1.32 (1.06, 1.64) |

0.57 0.012 |

0.96 (0.77, 1.19) 1.07 (0.86, 1.32) |

0.69 0.56 |

0.75 (0.59, 1.95) 0.89 (0.71, 1.12) |

0.02 0.33 |

0.84 (0.65, 1.08) 0.92 (0.72, 1.18) |

0.16 0.50 |

| Chronic disease | 1.68 (1.38, 2.04) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.31, 1.69) | ˂0.001 | 0.93 (0.83, 1.05) | 0.24 | 1.09 (0.96, 1.23) | 0.18 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 0.85 |

| Influenza/ILI in 2016/17 season | N/A | N/A | 0.78 (0.67, 0.90) | ˂0.001 | 1.82 (1.57, 2.12) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.09, 1.47) | 0.002 | 1.23 (1.05, 1.43) | 0.01 |

| Typically receive influenza vaccine | N/A | N/A | 1.18 (1.03, 1.34) | 0.015 | 3.48 (2.78, 4.39) | <0.001 | 3.50 (2.71, 4.56) | <0.001 | ||

| Satisfied with current vaccine | 60.49 (49.87, 73.80) | <0.001 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.35 (1.92, 2.88) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.60, 2.50) | <0.001 |

| Perceive need for new vaccine | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.84 (1.62, 2.10) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.41, 1.85) | <0.001 |

The factors significantly associated with higher odds of feeling satisfied by the current influenza vaccine were being 75 years and older, male, living in a city rather than a village, having one or more chronic conditions, and not having had influenza/ILI in the previous season.

Being male, typically receiving the influenza vaccine (every other year or more), and having had influenza or ILI in the previous season were factors significantly associated with perceiving the need for a new influenza vaccine.

Those 65–74 years, male, residing in a village rather than a town or city, having had influenza or ILI in the previous season, receiving the influenza vaccine at least every other year, feeling satisfied with the current influenza vaccine and perceiving the need for a new influenza vaccine were all factors significantly associated with increased odds of opting for HD vaccine if it was available for free.

Factors that were significantly associated with opting for HD even if it was available at a cost (depending on the cost) were being male, having had influenza or ILI in the previous season, typically receiving the influenza vaccine, being satisfied with the current influenza vaccine, and perceiving the need for a new influenza vaccine.

Discussion

Given the potential for serious adverse consequences of influenza for older adults, it is important to ensure that seniors have the information that they need to make vaccine-related decisions that optimally protect their health. Our study shows that while older adults in Canada initially felt satisfied with the publicly funded standard-dose vaccines, once presented with further information on the subject, the majority believe that a more effective vaccine may be/is needed. They may have some misconceptions and uncertainty regarding the severity of influenza which affects their vaccination decision-making. When seniors are presented with non-biased information about the effectiveness of influenza vaccines that are approved for use in Canada, they commonly opt for HD vaccine, although less so if HD is only available at a cost.

We were surprised to note the proportion of individuals who indicated at the beginning of the survey that they did not typically receive the influenza vaccine later report that they would opt for one next season. The information on influenza and influenza vaccines that they read as part of the survey (statements from PHAC and the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) on the clinical impact of influenza and influenza vaccine descriptions, respectively) may have contributed to this purported change in future behaviour. It is not possible to determine at this time whether this was an immediate and short-term reaction or indicative of a lasting change in opinion, but it does provide support for the use of targeted educational interventions which provide a balanced perspective on the effectiveness of the vaccine options. A large study of seniors in nine countries has demonstrated that perceptions of influenza vaccines are based on their own assumptions about the severity of influenza, their personal risk, and their beliefs about vaccine effectiveness, and that vaccine uptake could be positively affected by cues to take actions (or example, reminders, and recommenders from HCP).20 A US study in seniors found that a single targeted education effort in the form of a video increased respondent knowledge and influenza vaccination acceptance.21 The educational video intervention also increased the proportion of those willing to pay and the amount they were willing to pay even in those who indicated that they never typically receive the vaccine.21 Other studies have explored the use of short educational pamphlets and briefs to convey the severity of influenza and the importance of vaccination to avoid possible vaccine preventable disease.22 These tools follow the extended parallel process model (EPPM) method of using educational tools to arouse fear in users – in this case, the fear of influenza consequences, and the desire to engage in behaviour to avoid these consequences.23

Our study results indicate that while many seniors felt satisfied with standard-dose influenza vaccines, they did harbour concern that they were not receiving adequate protection. Among the vaccines discussed (standard-dose, HD and standard-dose adjuvanted), HD vaccine was most commonly chosen if it was available for free, furthering this notion. Those who would opt for HD include both those who typically receive the standard-dose vaccine, as well as a portion of the influenza vaccine hesitant population who do not usually receive the influenza vaccine because of their belief that it is ineffective or unnecessary; these beliefs have long been considered a barrier for older adults.24 Therefore, it is likely that providing HD as a publicly funded option would increase immunization rates in the senior population.

Of the 1426 respondents who indicated that they may be willing to pay for HD vaccine, 63% reported that they would pay less than $20. It is interesting to note the cost value that respondents place on influenza vaccines given that over the last decade, many Canadian provinces have adopted a universal influenza immunization program, offering public funding of standard-dose TIV for everyone over the age of six months. However, even before this time, seniors have long been considered high-risk individuals for influenza, and have been included in publicly funded groups. Therefore, many of the respondents have not recently needed to consider the cost of influenza vaccine, and as such, it is not likely to be top of mind. This is further demonstrated by this population not prioritizing cost of vaccine in key considerations for provincial governments as they decide whether or not to fund an influenza vaccine. We observed considerable variation across provinces in both perceptions of the need for HD, and the willingness to pay for this vaccine; it is worthwhile for provincial decision-maker to consider the receptiveness of their jurisdiction when introducing new vaccine options. Compared to other provinces, smaller percentages of respondents from Quebec and New Brunswick were willing to pay for HD vaccine. These two provinces are among the four with lowest income per resident.25 Additionally, Quebec has one of the lowest influenza vaccination rates for seniors.8 The same has not been demonstrated in New Brunswick, and further research is needed to understand this result.

Few respondents were willing to pay $50 or more for HD vaccine, but we noted that within this small subset, there was a trend towards a higher proportion of those who reported having influenza/ILI dosing so compared to those who had not been ill. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it may indicate that recent experience with this infectious disease could motivate those afflicted to avoid future recurrences. Prior studies have examined willingness to pay for influenza vaccine or influenza prevention in younger populations – working adults in the US were willing to pay $25 to avoid acquiring influenza.26 Ideally, the most effective vaccine would always be publicly funded, but with provincial budgets being limited, vaccine cost must be a key consideration in decision-making. The effectiveness of HD vaccine comes at a cost that is two to three times more expensive than standard-dose vaccine.27 Beyond an all or nothing approach to including HD vaccine for older adults as part of publically funded influenza vaccination campaigns, another way to consider these issues of willingness to pay would be a shared cost or co-pay model, in which the cost of the standard dose vaccine would be covered by the provincial program, whichever product the older adult chose to receive. If they did opt for a more expensive HD product, they could be invited to pay the difference. This additional choice might have the advantage of increasing vaccination rates while keeping the excess cost to individuals below the willingness to pay threshold. However, this arrangement results in provinces purchasing smaller amounts of multiple vaccines and therefore may decrease their purchasing power, thereby reducing the cost-effectiveness of this approach. Additionally, a co-pay model approach would perpetuate disadvantages for older adults with lower socioeconomic status, who are arguably among the most vulnerable to influenza and its complications, as they would be less likely to be able to pay the difference to access the HD vaccine.

Our study is not without limitations. As with any survey which asks about preferences and willingness to pay for a particular product, it is not possible to determine whether the responses provided are an accurate indication of future behaviour. We also did not share information about the side effects of the vaccines. Although HD has been found to have a rate of major adverse events that is similar to standard-dose TIV, previous studies indicate that it carries a higher risk of minor adverse events such as pain and swelling at the injection site.17 We cannot exclude that, if provided to survey respondents, this knowledge may have impacted decision-making. In indicating their willingness to pay for HD, respondents were provided ranges only as response options. This approach limits the extent of results interpretation but given that respondents were likely to find a specific range to be acceptable rather than have a clear cost threshold, we felt that this approach would likely yield the most realistic responses. We opted not to include discussion of trivalent vs. quadrivalent vaccine in this study; given that NACI states that trivalent HD vaccine should provide superior protection to standard-dose vaccines for older adults, we did not feel it was necessary to describe a fourth vaccine which might lead to respondent confusion. Also, quadrivalent influenza vaccines are offered as the standard-dose vaccine of choice in some jurisdictions as it stands. Therefore, we cannot comment on how responses may have differed if we had specifically included quadrivalent vaccine as a preference option in this study. Finally, our study focused on evaluating perception of dose and adjuvant rather than strains.

Our findings provide significant insight regarding the attitudes and behaviors of Canadian seniors towards influenza and influenza vaccines. We have demonstrated that although most seniors do feel satisfied with standard-dose influenza vaccines, many seek better protection, particularly those who have recently experienced influenza. Public funding of new, proven products with superior effectiveness is likely to result in increased immunization rates in this high-risk population.

Patients and methods

In March/April 2017, we conducted a quantitative study comprising an online survey (available in English and French) of Canadian seniors, called EXamining the Knowledge, Attitudes and Experiences of Canadian Seniors Towards Influenza (EXACT).

Study design

Our research team developed a survey comprising 25 multiple choice, true/false, and Likert scale of agreement questions about the respondents’ influenza vaccination practices, experiences with influenza during the 2016/17 season (defined as October 2016 to the time of survey completion), and knowledge about influenza (results reported elsewhere). Respondents were asked to report their age, gender, province/territory of residence, community size, and chronic conditions.

Vaccination history was obtained by asking whether respondents received the influenza vaccine annually, whether they had received it during the 2016/17 season, and whether they had been told by a healthcare provider (HCP) that they had influenza, or had experienced an undiagnosed influenza-like illness (ILI) that consisted of sore throat, fever, runny nose and cough.

Participants were also asked about their satisfaction with standard-dose vaccines and whether they perceived a need for a more effective product. In order to ensure that all respondents had a baseline knowledge about influenza, we provided them with the following statement about influenza from Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC): “The Public Health Agency of Canada has stated that adults 65 and over are more likely than people under 65 to get influenza-related complications (like pneumonia) or be hospitalized because of complications of influenza.”28 We then asked whether their level of satisfaction with the publicly-funded standard-dose vaccines changed after reading this statement. We also provided respondents with the following information about approved influenza vaccines in Canada, which referenced NACI’s 2016/2017 statement on influenza prevention29:

There are three influenza vaccines that have been approved in canada

1. Regular-dose influenza vaccine: This vaccine was approved several decades ago for Canadians over six months of age. Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization states that in those 65 years and over, this vaccine’s effectiveness is “about half of that in healthy adults” but that “vaccinated individuals are still more likely to be protected compared to those who are unvaccinated.” This vaccine is available at no cost in all provinces.

2. Regular-dose adjuvanted influenza vaccine: This vaccine was approved in 2011 for Canadians 65 years and older. It contains an adjuvant, which is a substance that is added to a vaccine to enhance the person’s immune response. Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization has stated that “there is evidence from randomized controlled trials that adjuvanted influenza vaccine induces higher immunogenicity (immune response) in adults 65 years of age and older” compared to regular-dose influenza vaccine. This vaccine is available at no cost in some provinces.

3. High-dose influenza vaccine: This vaccine was approved in 2015 for Canadians 65 years and older. It has 4 times the dose of the regular-dose influenza vaccine and the regular-dose adjuvanted influenza vaccine. Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization has stated that “there is evidence that high-dose influenza vaccine should provide better protection and the greatest benefit against influenza compared with the regular-dose influenza vaccine for adults 65 years and older.”

We substituted the term regular-dose for standard-dose. We did not include specific information about quadrivalent vs. trivalent influenza vaccines, for ease of comprehension and because QIV is offered as the “regular-dose” product in some jurisdictions.

We asked about vaccine preference for the next season should HD be publicly funded or only available at a cost, as well as willingness to pay for HD vaccine. Given that vaccination is under provincial jurisdiction, we also asked how respondents would feel if an influenza vaccine that was thought to provide superior benefit to those currently available was publicly funded in a neighbouring province but not their own. Finally, respondents were given a list and asked to select key priorities that their provincial government should consider when deciding whether or not to fund an influenza vaccine.

We disseminated this survey to Canadians 65 years of age and older, through market research company Leger Marketing’s national online polling panel. This panel consists of 400,000 Canadians who were initially recruited over the telephone, through referrals and affiliate programs, partner programs, offline recruitment, and social media. Panel members are given a dollar incentive based on length of completed survey. Leger implements various strategies including data verification questions, analysis of response patterns and times (to identify those completing the surveys in an unusually quick manner indicating less than careful consideration of the questions) to reduce the risk of respondents “gaming the system” for the incentives.

Participants were eligible if they were 65 years and older (approximately 10.5% of the total panel). Leger disseminated the survey via an emailed link, sampling proportionately to province population to achieve a sample size of approximately 5,000 respondents (calculated based on expected response to a question about preferences regarding different influenza vaccines). The research team did not provide any additional compensation.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on a question asking, “Which flu shot would you prefer to receive next year, assuming both vaccines are available for free?” We assumed that of all respondents, 45% would be either equally comfortable with HD vaccine or standard-dose vaccine, or be against all influenza vaccines, while the remaining 55% would express a preference for either HD vaccine or standard-dose vaccine.

To detect a difference of 5% in the proportion of survey respondents that chose standard-dose (25%) vs. HD vaccine (30%), with 80% power, a total of 746 respondents were required, using the single-sample test for binary distribution.30

To account for the remaining respondents (45%), a sample size of 610 = 746*45/55 was required. Therefore, the total sample size needed to detect a 5% difference between the groups was 1356. We opted for a larger sample size than originally estimated because this allowed us to examine secondary outcomes which may not have otherwise been sufficiently powered.

Analysis

Survey data were analyzed overall, and by respondent demographics, medical history and province. Continuous variables were compared using two sample t-tests and proportions were compared using Chi-Square tests or Fisher’s exact tests. Two-sided tests were used for all statistical analyses unless specified. We conducted a post-hoc analysis of just respondents who indicated that they had never or did not typically receive the influenza vaccine annually, since this is a population known to be challenging to effectively target and whose behaviours and perceptions are of particular interest from a public health perspective.

We conducted logistic regression to identify respondent characteristics and opinions that were significantly associated with higher odds of typically receiving the influenza vaccine annually, satisfaction with the current vaccine, perceiving the need for a new vaccine, and opting for HD vaccine if it was available next season free or at a cost.

We used STATA version 10.0 (2007, StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX) for analyses

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

JAP has acted as a consultant for Sanofi Pasteur. NW has funding from Merck and GSK. MKA reports grants from GSK and Pfizer in collaboration with CIHR and PHAC, and Sanofi in collaboration with Canadian Frailty Network.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Canadian Frailty Network, which is supported by the Government of Canada through the Network of Centres of Excellence (NCE) program, in partnership with Sanofi Pasteur Canada.

Acknowledgment

This study was approved by the Nova Scotia Health Authority’s Research Ethics Board.

References

- 1.Kwong JC, Ratnasingham S, Campitelli MA, Daneman N, Deeks SL, Manuel DG, Allen VG, Bayoumi AM, Fazil A, Fisman DN, et al. The impact of infection on population health: Results of the Ontario Burden of Infectious Diseases Study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e44103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols KL. Influenza vaccination in the elderly: impact on hospitalization and mortality. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(6):495–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, Burant CJ, Landefeld CS. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003. April;51(4):451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrew MK, MacDonald S, Ye L, Ambrose A, Boivin G, Diaz-Mitoma F, Bowie W, Chit A, Dos Santos G, Elsherif M, et al. on behalf of CIRN SOS and TIBDN Network Investigators . Impact of frailty on influenza vaccine effectiveness and clinical outcomes: experience from the Canadian Immunization Research Network(CIRN) Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) network 2011/12 season. Can Immunization Conf Abstract. 2016;3(suppl_1):s136. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofw172.573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrew MK, Lees C, Godin J, Black K, McElhaney J, Ambrose A, Boivin G, Bowie WR, Elsherif M, Green K, et al. Frailty hinders recovery from acute respiratory illness in older adults. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2017;4(suppl 1):S573–574. doi:org/10.1093/ofid/ofx163.1500. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Government of Canada Provincial and territorial immunization information. [accessed 2018 July03]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information.html

- 7.Public Health Agency of Canada Final report of outcomes from the national consensus conference for vaccine-preventable diseases in Canada: june 12-14, 2005 - Quebec City, Quebec. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2008. March;34S2 [accessed 2016 August17]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/08vol34/34s2/index-eng.php, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gionet L. Flu vaccination rates in Canada. Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 82-624-X. [accessed 2016 August16]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2015001/article/14218-eng.htm.

- 9.Beyer WE, McElhaney J, Smith DJ, Monto AS, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Osterhaus ADME. Cochrane re-arranged: support for policies to vaccinate elderly people against influenza. Vaccine. 2013;31(50):6030–6033. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao W, Kim JH, Chirkova T, Reber AJ, Biber R, Shay DK, Sambhara S. Improving immunogenicity and effectiveness of influenza vaccine in older adults. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(11):1529–1537. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Della Bella S, Iorio AM, Michel J-P, Pawelec G, Solana R. Immunosenescence and vaccine failure in the elderly. Aging-Clinical Exp Res. 2009;21(3):201–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03324904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(3):379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen H, Nguyen K, Mao L, Marcoux R, Gao R, Nair C. Influenza Vaccination. Health Rep (Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003) 2004;15(2):33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagata JM, Hernández-Ramos I, Kurup AS, Albrecht D, Vivas-Torrealba C, Franco-Paredes C. Social determinants of health and seasonal influenza vaccination in adults ≥65 years: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:388. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telford R, Rogers A. What influences elderly peoples’ decisions about whether to accept the influenza vaccination? A qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(6):743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Public Health Agency of Canada (2016). An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): a review of the literature of high dose seasonal influenza vaccine for adults 65 years and older. [accessed 2016 August17]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/naci-ccni/assets/pdf/influenza-vaccine-65-plus-vaccin-contre-la-grippe-65-plus-eng.pdf.

- 18.DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:635–645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrew M, Gilca V, Waite NM, Pereira JA. EXamining the knowledge, attitudes and experiences of Canadian seniors towards influenza (the EXACT survey). (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwong EW, Pang SM, Choi P. Influenza vaccine preference and uptake among older people in nine countries. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66((10):2297–2298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worasathit R, Wattana W, Okanurak K, Songthap A, Dhitavat J, Pitisuttithum P. Health education and factors influencing acceptance of and willingness to pay for influenza vaccination among older adults. BMC Geriatrics. 2015;15:.136. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho HJ, Chow A. The impact of short educational messages in motivating community-dwelling seniors to receive influenza and pneuomococcal vaccines. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45(Supp 1):226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witte K. Fear control and danger control: a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Communications Monogr. 1994;61(2):113–134. doi: 10.1080/03637759409376328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wooten KG, Wortley PM, Singleton JA, Euler GL. Perceptions matter: beliefs about influenza vaccine and vaccination behavior among elderly white, black and Hispanic Americans. Vaccine. 2012;30:6927–6934. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Conference Board of Canada Income per Capita. [accessed 2018 August14]. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/provincial-fr/economy-fr/income-per-capita-fr.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- 26.Johnston SS, Rousculp MD, Palmer LA, Chu BC, Mahadevia PJ, Nichol KL. Employees’ willingness to pay to prevent influenza. Am J Managed Care. 2010;16(8):e205–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chit A, Roiz J, Briquet B, Greenberg DP. Expected cost effectiveness of high-dose trivalent influenza vaccine in US seniors. Vaccine. 2015;33(5):734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Government of Canada Risks of flu (influenza). [accessed 2017 December18]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/flu-influenza/risks-flu-influenza.html.

- 29.Government of Canada Canadian immunization guide chapter on influenza and statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2016-2017. [accessed 2017 December18]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/canadian-immunization-guide-chapter-on-influenza-statement-on-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-2016-2017-advisory-committee-statement.html.

- 30.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]