Abstract

Objectives

With aging of the HIV-positive population, cardiovascular disease (CVD) increasingly contributes to morbidity and mortality. We investigated CVD-related and other causes of death (COD) and factors associated with CVD in a multi-country Asian HIV-positive cohort.

Methods

Patient data from 2003–2017 was obtained from the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD). We included patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) with >1 day of follow-up. Cumulative incidences were plotted for CVD-related, AIDS-related, non-AIDS-related, and unknown COD, and any CVD (i.e. fatal and non-fatal). Competing risk regression was used to assess risk factors of any CVD.

Results

Of 8069 patients with a median follow-up of 7.3 years (IQR 4.4–10.7), 378 patients died (incidence rate [IR] 6.2 per 1000 person-years [pys]), including 22 CVD-related deaths (IR 0.36 per 1000pys). Factors significantly associated with any CVD event (IR 2.2 per 1000pys) were older age (sHR 2.21, 95%CI 1.36–3.58 for age 41–50 years; sHR 5.52, 95%CI 3.43–8.91 for ≥51 years, compared to <40 years), high blood pressure (sHR 1.62, 95%CI 1.04–2.52), high total cholesterol (sHR 1.89, 95%CI 1.27–2.82), high triglycerides (sHR 1.55, 95%CI 1.02–2.37) and high BMI (sHR 1.66, 95%CI 1.12–2.46). CVD crude incidence rates were lower in later ART initiation period and lower- or upper-middle income countries.

Conclusion

The development of fatal and non-fatal CVD events in our cohort was associated with older age, and treatable risk factors such as high blood pressure, triglycerides, total cholesterol and BMI. Lower CVD event rates in middle-income countries may indicate under-diagnosis of CVD in Asian-Pacific resource-limited settings.

Keywords: HIV, cardiovascular disease, cause of death, risk factors, Asia

Introduction

Globally, AIDS-related mortality is declining and life expectancy for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) is increasing, largely due to the increased uptake of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [1]. As a result, comorbidities not related to AIDS, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), are becoming increasingly important in the management of long term HIV infection. This is of particular concern because PLHIV are prone to developing coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction and other CVD events due to a combination of aging, other traditional CVD risk factors, and HIV-related risk factors, such as chronic inflammation and ART use [2, 3].

Data from high-income settings suggest that a considerable number of PLHIV have CVD, and associated fatal and non-fatal outcomes. The D:A:D cohort of PLHIV from Europe and Australia found a CVD event rate of 4.9 per 1000 person-years (1000pys) [4]. Of the total number of CVD events, approximately 16% were fatal events. The D:A:D cohort also indicated that 11% of overall mortality was caused by CVD [5]. CVD mortality rates have been found to differ substantially by region, with a CVD death rate of 1 and 0.6 per 1000pys in European men and women, respectively, whereas the rate was almost double that in Canada, with 2.3 and 1.2 CVD-related deaths per 1000pys [6].

There is limited data on CVD-related morbidity and mortality among PLHIV in the Asia-Pacific region. One recent study from Taiwan showed a stroke incidence of 2.5 per 1000pys in PLWHIV [7]. Furthermore, a multi-country study conducted ten years ago estimated that 6.5 % of overall mortality in Asia was caused by CVD [8]. With the aging of Asian HIV-positive populations [9] and unfavourable changes in lifestyle and health behaviour [10], CVD is likely to become an increasing cause for concern in this region. Since understanding the epidemiology of CVD amongst PLHIV is essential to better manage HIV and comorbid CVD, we aimed to explore CVD-related and other cause-specific mortality and investigate factors associated with CVD events in an Asian multi-country HIV-positive cohort.

Methods

Study design and patients

The study population consisted of patients enrolled in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD), a prospective observational cohort of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS which has previously been described in detail [11, 12]. Briefly, HIV-positive adults (≥18 years) were enrolled from 2003 onward at 20 clinical sites in 12 Asian countries and territories. For the current study, we used all follow-up data up to the September 2017 data transfer. We included patients who were on combination ART and had at least one day of follow-up after ART initiation or cohort entry date.

Outcomes

Cause of death (COD) was reported by clinicians at the study site using the CoDe case report form (CRF) for coding causes of death (http://www.chip.dk/Tools-Standards/CoDe), which includes details of autopsy reports where relevant. The CoDe CRFs were reviewed by independent HIV specialists who determined primary and secondary causes of death. COD was classified as unknown if insufficient information was obtained. For this study, causes of death from the CoDE CRFs were categorized as CVD-related, AIDS-related, non-AIDS-related and unknown. Non-AIDS-related deaths were further subdivided into death caused by cancer, infection, suicide/drug overdose/accidental or violent death, liver disease, and other. Because of the relatively small number of fatal CVD events, a composite endpoint was created of any non-fatal CVD event and death due to CVD. CVD comprised of stroke, myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, coronary heart disease, and congestive heart failure as recorded on patient medical charts. All CVD diagnoses were validated at site level.

Statistical analysis

CVD-related and other cause-specific mortality.

The cumulative incidence of different causes of death were plotted using the competing risk framework in which each COD was a competing risk for the other causes of death [13]. Follow-up time was censored at death, lost to follow-up (LTFU, defined as having no clinic visit in the 12 months prior to data transfer), transfer to another clinic, or last clinic visit. We calculated mortality rates per 1000pys of follow-up. Cumulative incidence curves were stratified by period of ART initiation.

Factors associated with CVD.

Fine and Gray competing risk regression [14] was used to identify factors associated with CVD. The outcome of interest was the composite endpoint of fatal and non-fatal CVD events, with deaths not due to CVD treated as a competing risk. We provided CVD incidence rates per 1000pys and calculated sub-hazard ratios (sHR) for the association between the potential risk factors and CVD. Risk factors considered were sex, age at ART initiation (≤40, 41–50 or ≥51), HIV exposure category (heterosexual contact, homosexual contact, injecting drug use, or other), HIV viral load (<50, 50–399 vs ≥400 copies/mL), CD4 count (<200, 200–349, 350–499 vs ≥500 cells/μL), baseline ART regimen (NNRTI-based vs PI-containing/other), period of ART initiation (≤2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2009 or ≥2010), ever having tested positive on a HBsAg or Anti-HCV test, ever having smoked, and presence of other CVD risk factors, e.g. high blood pressure systolic blood pressure>140 or diastolic blood pressure>90 mmHg), high fasting plasma glucose (>7.0 mmol/L), low HDL (<1.0 mmol/L), high total cholesterol (≥5.2 mmol/L), high triglycerides (≥1.7 mmol/L), and body mass index (<25 or ≥25 kg/m2). HIV viral load, CD4 count and CVD risk factors, except for ever having smoked, were used as time-updated variables. Multivariable regression was conducted using a stepwise backwards selection procedure, including all covariates that were significant at p<0.10 in univariate analysis. The final model included all covariates that remained significant at the five percent alpha level.

Data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata software version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained at all participating sites, the data management and analysis center (The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, Australia), and the coordinating center (TREAT Asia/amfAR, Bangkok, Thailand).

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of the 8069 included patients. At ART initiation, median age in our study population was 34 years (IQR 29–41) and the majority of patients were men (70%). The median CD4 count was 132 cells/μL (IQR 42–236) and the median viral load was log10 5.0 copies/mL (IQR 4.4–5.4). The majority were on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) regimen (86%), started ART after 2005 (67%) and were from lower-middle income countries (46%). With regard to CVD risk factors, at ART initiation a small proportion of patients had known high blood pressure (5%), high fasting plasma glucose (1%), high total cholesterol (4%) low HDL (10%), high triglycerides (11%), or were overweight (8%), whereas ever having smoked was more common (32%). Throughout follow-up, the majority of patients was tested on viral load (90%), CD4 count (>99%), blood pressure (84%), fasting plasma glucose (80%), total cholesterol (80%), HDL (67%), triglycerides (79%), and BMI (85%). Information on ever smoking was only available in part of the patients (71%). There were 378 (5%) deaths, 1112 (14%) transfers, 1017 (12 %) LTFU, and 5562 (69%) in active follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at ART initiation (N=8069)

| Total patients | CVD deaths | Other deaths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 2386 | 29.6% | 6 | 27.3% | 73 | 20.5% |

| Male | 5683 | 70.4% | 16 | 72.7% | 283 | 79.5% |

| Age at ART initiation (years) | ||||||

| ≤40 | 5989 | 74.2% | 8 | 36.4% | 218 | 61.2% |

| 41–50 | 1472 | 18.2% | 7 | 31.8% | 70 | 19.7% |

| ≥51 | 608 | 7.5% | 7 | 31.8% | 68 | 19.1% |

| HIV exposure category | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 5014 | 62.1% | 17 | 77.3% | 237 | 66.6% |

| Homosexual | 1843 | 22.8% | 5 | 22.7% | 45 | 12.6% |

| Other | 1212 | 15.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 74 | 20.8% |

| Country income group | ||||||

| High | 1608 | 19.9% | 7 | 31.8% | 74 | 20.8% |

| Upper-middle | 2747 | 34.0% | 4 | 18.2% | 103 | 28.9% |

| Lower-middle | 3714 | 46.0% | 11 | 50.0% | 179 | 50.3% |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | ||||||

| <50 | 72 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 50–399 | 93 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.8 |

| ≥400 | 3779 | 46.8 | 12 | 54.5 | 155 | 43.6 |

| Missing | 4125 | 51.1 | 10 | 45.5 | 197 | 55.3 |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | ||||||

| ≥500 | 212 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.4 |

| 350–499 | 384 | 4.8 | 1 | 4.6 | 12 | 3.4 |

| 200–349 | 1740 | 21.6 | 3 | 13.6 | 37 | 10.4 |

| <200 | 4572 | 56.6 | 15 | 68.2 | 265 | 74.4 |

| Missing | 1161 | 14.4 | 3 | 13.6 | 37 | 10.4 |

| ART regimen | ||||||

| NNRTI | 6927 | 85.8% | 17 | 77.3% | 313 | 87.9% |

| PI/other | 1142 | 14.2% | 5 | 22.7% | 43 | 12.1% |

| Period of ART initiation | ||||||

| ≤2002 | 970 | 12.0% | 2 | 9.1% | 55 | 15.4% |

| 2003–2005 | 1683 | 20.9% | 5 | 22.7% | 119 | 33.4% |

| 2006–2009 | 2760 | 34.2% | 10 | 45.5% | 116 | 32.6% |

| ≥2010 | 2656 | 32.9% | 5 | 22.7% | 66 | 18.5% |

| Positive HBsAg test* | ||||||

| No | 5650 | 70.0 | 12 | 54.6 | 225 | 63.2 |

| Yes | 643 | 8.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 38 | 10.7 |

| Missing/not tested | 1776 | 22.0 | 7 | 31.8 | 93 | 26.1 |

| Positive Anti-HCV test* | ||||||

| No | 4951 | 61.4 | 13 | 59.1 | 185 | 52.0 |

| Yes | 882 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 69 | 19.4 |

| Missing/not tested | 2236 | 17.7 | 9 | 40.9 | 102 | 28.6 |

| High blood pressure | ||||||

| No | 3899 | 48.3% | 9 | 40.9% | 164 | 46.1% |

| Yes | 314 | 3.9% | 1 | 4.5% | 14 | 3.9% |

| Not tested/missing | 3856 | 47.8% | 12 | 54.5% | 178 | 50.0% |

| Fasting plasma glucose(mmol/L) | ||||||

| ≤7.0 | 2872 | 35.6% | 8 | 36.4% | 101 | 28.4% |

| >7.0 | 68 | 0.8% | 1 | 4.5% | 2 | 0.6% |

| Not tested/missing | 5129 | 63.6% | 13 | 59.1% | 253 | 71.1% |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | ||||||

| <5.2 | 2556 | 31.7% | 8 | 36.4% | 77 | 21.6% |

| ≥5.2 | 349 | 4.3% | 1 | 4.5% | 13 | 3.7% |

| Not tested/missing | 5164 | 64.0% | 13 | 59.1% | 266 | 74.7% |

| HDL (mmol/L) | ||||||

| ≥1.0 | 658 | 8.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | 4.2% |

| <1.0 | 771 | 9.6% | 2 | 9.1% | 24 | 6.7% |

| Not tested/missing | 6640 | 82.3% | 20 | 90.9% | 317 | 89.0% |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | ||||||

| <1.7 | 1522 | 18.9% | 2 | 9.1% | 45 | 12.6% |

| ≥1.7 | 854 | 10.6% | 3 | 13.6% | 35 | 9.8% |

| Not tested/missing | 5693 | 70.6% | 17 | 77.3% | 276 | 77.5% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <25 | 4334 | 53.7% | 11 | 50.0% | 205 | 57.6% |

| ≥25 | 619 | 7.7% | 2 | 9.1% | 18 | 5.1% |

| Not tested/missing | 3116 | 38.6% | 9 | 40.9% | 133 | 37.4% |

| Ever smoked~ | ||||||

| No | 3215 | 39.8% | 5 | 22.7% | 49 | 13.8% |

| Yes | 2574 | 31.9% | 5 | 22.7% | 63 | 17.7% |

| Unknown | 2280 | 28.3% | 12 | 54.5% | 244 | 68.5% |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI, body mass index.

HBsAg and anti-HCV test on ever tested positive throughout follow-up;

Ever smoked before ART initiation or throughout follow-up.

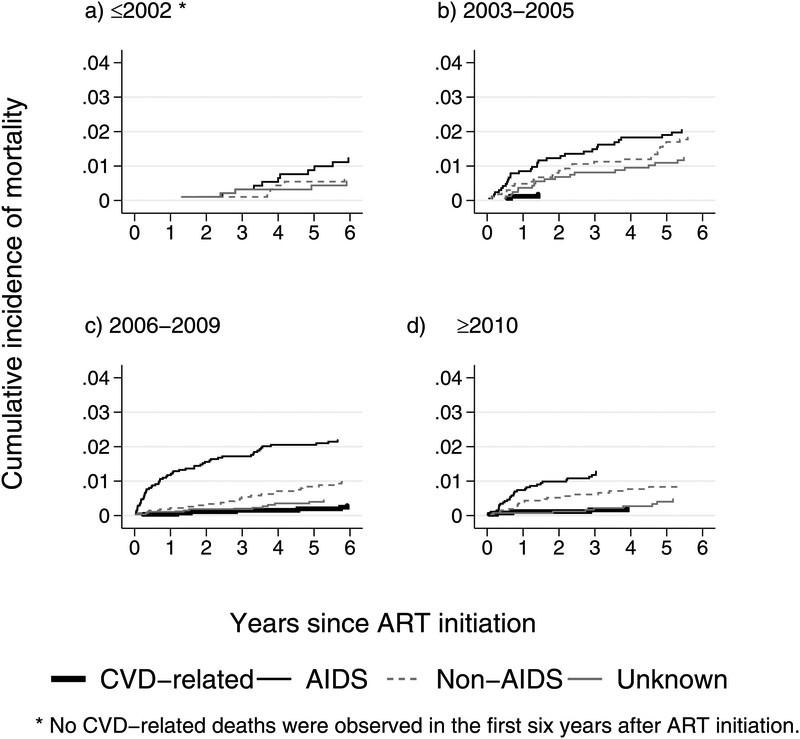

CVD-related and other cause-specific mortality

The median follow-up time in our study was 7.3 years (IQR 4.4–10.7) and the overall mortality rate was 6.2 per 1000pys. In total, 22 deaths were CVD related (0.36 per 1000pys). The remaining deaths were AIDS related (158 deaths, 2.6 per 1000pys) or non-AIDS related (128 deaths, 2.1 per 1000pys), such as cancer (20 deaths, 0.33 per 1000pys), infection (31 deaths, 0.51 per 1000pys), suicide/drug overdose/accident/violence (24 deaths, 0.39 per 1000pys), liver (26 deaths, 0.42 per 1000pys), other causes (27 deaths, 0.44 per 1000pys), or unknown causes (70 deaths, 1.1 per 1000pys) (Table 2). There were no recorded CVD-related deaths during the first six years on ART (Figure 1a) among patients who started ART prior to 2003. However, for those initiating ART in later periods, CVD-related COD became more pronounced (Figure 1b–d). Over time, AIDS remained the most common COD, compared to CVD-related, other non-AIDS-related, and unknown COD, with most of the deaths occurring in the first two years after ART initiation (Figure 1a–d).

Table 2.

Causes of death in TAHOD

| Causes of death | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease-related | 22 | 5.8 |

| AIDS-related | 158 | 41.8 |

| Non-AIDS related | ||

| Cancer | 20 | 5.3 |

| Infection | 31 | 8.2 |

| Suicide/drug overdose/accident/violence | 24 | 6.4 |

| Liver | 26 | 6.9 |

| Other | 27 | 7.1 |

| Unknown | 70 | 18.5 |

| Total | 378 | 100 |

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of causes of death during the first six years on ART, by period of ART initiation

Factors associated with CVD

Table 3 shows the associations between risk factors and the composite endpoint of fatal and non-fatal CVD events. During 60719pys at risk, 132 patients experienced a CVD event (2.2 per 1000pys). In the univariate analysis, sex, age group, HIV exposure category, country income group, ART regimen, ART start year, anti-HCV test, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides and BMI were associated with having a CVD event. In the multivariate analysis, patients aged 41–50 and ≥51 years at ART initiation had a higher hazard for CVD (sHR 2.21, 95%CI 1.36–3.58 and sHR 5.52, 95%CI 3.43–8.91, respectively) compared to those aged ≤40 years. The crude incidence rate in high-income countries was higher than both upper-middle and lower-middle-income countries, however, the sHR was only statistically significant for upper-middle income countries, compared to high-income countries (sHR 0.15, 95%CI 0.08–0.28). Later periods of ART initiation were associated with a lower hazard of having CVD (2006–2009: sHR 0.60 95%CI 0.36–0.98, and ≥2010: sHR 0.44 95%CI 0.23–0.83, compared to ≤2002). Patients with high blood pressure (sHR 1.62, 95%CI 1.04–2.52), high total cholesterol (sHR 1.89, 95%CI 1.27–2.82), high triglycerides (sHR 1.55, 95%CI 1.02–2.37) and high BMI (sHR 1.66, 95%CI 1.12–2.46) were more likely to have CVD events, whereas fasting plasma glucose, HDL, and smoking were not significantly associated with CVD.

Table 3.

Competing risk analysis of factors associated with CVD events

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-years | Events | IR (/1000pys) | sHR | 95CI | p-value | sHR | 95 CI | p-value | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 18446 | 20 | 1.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 42273 | 112 | 2.7 | 2.38 | 1.48–3.83 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 0.76–2.14 | 0.352 |

| Age (years)* | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| ≤40 | 33618 | 30 | 0.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 41–50 | 18097 | 41 | 2.3 | 2.54 | 1.57–4.12 | 0.001 | 2.21 | 1.36–3.58 | 0.001 |

| ≥51 | 9004 | 61 | 6.8 | 7.22 | 4.51–11.56 | <0.001 | 5.52 | 3.43–8.91 | <0.001 |

| HIV exposure category | <0.001 | <0.044 | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 39844 | 76 | 1.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Homosexual | 12839 | 48 | 3.7 | 2.01 | 1.40–2.89 | <0.001 | 1.41 | 0.96–2.07 | 0.083 |

| Other | 8037 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.54 | 0.26–1.12 | 0.099 | 0.61 | 0.29–1.27 | 0.182 |

| Country income group | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| High | 13293 | 69 | 5.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Upper-middle | 20459 | 12 | 0.6 | 0.12 | 0.06-0.22 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.08–0.28 | <0.001 |

| Lower-middle | 26967 | 51 | 1.9 | 0.39 | 0.27-0.56 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 0.48–1.09 | 0.125 |

| Viral load (copies/mL)* | 0.913 | 0.556 | |||||||

| <50 | 33257 | 78 | 2.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 50–399 | 8681 | 19 | 2.2 | 1.02 | 0.62–1.68 | 0.933 | 1.07 | 0.63–1.81 | 0.815 |

| ≥400 | 6904 | 19 | 2.8 | 1.12 | 0.67–1.88 | 0.669 | 1.38 | 0.77–2.48 | 0.282 |

| Not tested/missing | 11877 | 16 | 1.3 | - | |||||

| CD4 count (cells/μL)* | 0.270 | 0.282 | |||||||

| ≥500 | 21263 | 43 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 350–499 | 14877 | 31 | 2.1 | 1.15 | 0.73–1.82 | 0.552 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.79 | 0.593 |

| 200–249 | 13746 | 35 | 2.5 | 1.52 | 0.96–2.40 | 0.072 | 1.55 | 0.99–2.42 | 0.056 |

| <200 | 9130 | 16 | 1.8 | 0.99 | 0.55–1.76 | 0.959 | 1.14 | 0.63–2.06 | 0.672 |

| Not tested/missing | 1704 | 7 | 4.1 | - | - | ||||

| ART Regimen | |||||||||

| NNRTI | 50388 | 82 | 1.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| PI/other | 10331 | 50 | 4.8 | 2.78 | 1.94–3.99 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 0.85–2.26 | 0.188 |

| Period of ART initiation | 0.010 | 0.024 | |||||||

| ≤2002 | 11869 | 43 | 3.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2003–2005 | 15883 | 40 | 2.5 | 0.80 | 0.51–1.26 | 0.332 | 0.93 | 0.58–1.48 | 0.753 |

| 2006–2009 | 20658 | 33 | 1.6 | 0.52 | 0.32–0.85 | 0.009 | 0.60 | 0.36–0.98 | 0.043 |

| ≥2010 | 12310 | 16 | 1.3 | 0.43 | 0.24–0.80 | 0.005 | 0.44 | 0.23–0.83 | 0.011 |

| Positive HBsAg test | |||||||||

| No | 43253 | 105 | 2.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 4953 | 12 | 2.4 | 0.98 | 0.54–1.79 | 0.953 | 1.01 | 0.56–1.83 | 0.963 |

| Missing/not tested | 12513 | 15 | 1.2 | - | - | ||||

| Positive Anti-HCV test | |||||||||

| No | 38947 | 109 | 2.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 6044 | 8 | 1.3 | 0.48 | 0.23–0.98 | 0.045 | 0.84 | 0.40–1.79 | 0.658 |

| Missing/not tested | 15728 | 15 | 1.0 | - | - | ||||

| High blood pressure* | |||||||||

| No | 39621 | 69 | 1.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 6524 | 31 | 4.8 | 2.51 | 1.62–3.88 | <0.001 | 1.62 | 1.04–2.52 | 0.034 |

| Not tested/missing | 14574 | 32 | 2.2 | - | - | ||||

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)* | |||||||||

| ≤7.0 | 42167 | 95 | 2.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| >7.0 | 1000 | 8 | 8.0 | 3.25 | 1.56–6.75 | 0.002 | 1.86 | 0.87–3.99 | 0.112 |

| Not tested/missing | 17552 | 29 | 1.7 | - | - | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L)* | |||||||||

| <5.2 | 27355 | 44 | 1.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥5.2 | 16480 | 64 | 3.9 | 2.42 | 1.64–3.58 | <0.001 | 1.89 | 1.27–2.82 | 0.002 |

| Not tested/missing | 16884 | 24 | 1.4 | - | - | ||||

| HDL (mmol/L)* | |||||||||

| ≥1.0 | 24116 | 49 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| <1.0 | 8818 | 24 | 2.7 | 1.36 | 0.83–2.21 | 0.233 | 1.43 | 0.85–2.39 | 0.176 |

| Not tested/missing | 27786 | 59 | 2.1 | - | - | ||||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L)* | |||||||||

| <1.7 | 21906 | 31 | 1.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥1.7 | 20987 | 72 | 3.4 | 2.38 | 1.56–3.64 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.02–2.37 | 0.041 |

| Not tested/missing | 17826 | 29 | 1.6 | - | - | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2)* | |||||||||

| <25 | 39589 | 74 | 1.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥25 | 9641 | 38 | 3.9 | 2.13 | 1.44–3.15 | <0.001 | 1.66 | 1.12–2.46 | 0.011 |

| Not tested/missing | 11489 | 20 | 1.7 | - | - | ||||

| Ever smoking | |||||||||

| No | 26884 | 55 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 21977 | 55 | 2.5 | 1.21 | 0.83–1.75 | 0.327 | 1.00 | 0.68–1.47 | 0.998 |

| Unknown | 11858 | 22 | 1.9 | - | - | ||||

P-values for test for heterogeneity excluded missing or not-tested values. P-values in bold represent significant covariates in the final model. Non-significant factors were presented in the multivariate model adjusted for significant predictors.

IR, incidence rate; pys, person-years; sHR, sub-hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BMI, body mass index

Time-updated variables where each patient can contribute to more than one category.

Discussion

In our study population, the incidence of CVD-related COD was more pronounced in those who initiated ART in later years, however, AIDS-related illnesses remained the most common COD. A fatal or non-fatal CVD event was experienced by 132 patients. Factors associated with CVD were older age at ART initiation, period of ART initiation, high blood pressure, high total cholesterol, high triglycerides, and high BMI. Furthermore, CVD incident rates were associated with country income group, but not with any of the included HIV-specific risk factors.

In our study, AIDS remained the most common COD in the Asia-Pacific region. This is similar to other regions across the world [5, 6]. The majority of our study population started ART with low CD4 counts. Such patients are generally more likely to die in the first period after ART initiation and to die from AIDS-related causes [1]. There were similar death rates due to CVD and other causes (i.e. non-AIDS cancer, infection, suicide/drug overdose/accident/violence and liver disease). Unknown COD was still relatively common in TAHOD. Nevertheless, the rate of reporting COD has improved over time [8], and may indicate improved patient surveillance and reporting practices in more recent years.

The rate for developing any CVD event in TAHOD was 2.2 per 1000pys, while the rate for having a fatal CVD events was 0.36 per 1000pys. Corroborating other studies [15–17], our findings confirm that traditional risk factors such as older age and the presence of high blood pressure, blood lipid abnormalities and high BMI are important risk factors for developing CVD. Those aged >50 years had 5.5 times the hazard compared to those aged <40 years. This is consistent with other studies indicating the effect of aging on the increased risk of CVD [18–20]. Younger median age might also, in combination with prescription of ART regimens that are less detrimental to cardiovascular health, explain the reduced CVD hazard in the group of patients who started ART more recently. A further shift in the age distribution of the Asian HIV-positive population is expected as PLHIV live longer [9], raising the concern that in the upcoming years CVD event rates might rise to great extent. In our study, CVD was not significantly associated with male gender, high fasting plasma glucose, low HDL or smoking. However, apart from smoking, all these factors did show a trend, albeit non-statistically significant, of being unfavourable to cardiovascular health, as would be expected and has been confirmed in previous studies [15–17].

Smoking has been identified as a major risk factor for CVD in both the general population and PLHIV [4, 21, 22]. In our study, we did not find evidence for the association between smoking and CVD. This could possibly be due to the limited information on smoking status in our cohort. Data on smoking was routinely collected from year 2011 onwards, as such this information would not be readily available for follow-up periods prior to 2011. Additionally, it is likely that information on current smoking was not regularly updated. Therefore, we have categorised smoking status as “ever” smoked, rather than “current” smoker. Still, given the limited availability of smoking data, our study might not have been able to detect an effect of smoking on CVD in this population.

In our study the CVD incidence rate in the high country-income group was greater than in the upper-middle and lower-middle income countries. This contrasts with studies in the general population showing that event rates and the proportion of fatal events are lowest in high-income countries [23]. Our opposing findings may be related to data ascertainment as it is possible that not all CVD events were diagnosed due to a lack of resources in the middle-income countries. Differences may also be seen in CVD event rates between countries in similar income groups since they may have substantially different health systems, for instance in terms of availability of cheaper generic drugs [24]. Thus, some countries might be better equipped to decrease CVD risk with accessible drug treatment and thereby prevent CVD events.

It is reassuring that many of the risk factors we identified are of a modifiable nature and can be targeted with interventions. However, many patients in our study population had not been tested for abnormalities in blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose and lipid levels at ART initiation or during treatment. This is especially of concern as there was a relatively high rate of CVD events for those not tested. Significant improvement in CVD morbidity and mortality may be achieved with improved monitoring and management of CVD risk factors, as recommended by WHO treatment guidelines [25].

Our study had some limitations. First, we were unable to discern differences in risk factors for fatal and non-fatal CVD due to the limited number of events in our cohort. This might be related to the under diagnosis of CVD events. For instance, especially in lower resource settings, limited accessibility of appropriate screening and diagnostic tools may result in missed symptoms of CVD and thereby misdiagnosis of CVD events. In addition, patients from marginalized groups who are less likely to seek health care may not have been diagnosed with CVD or may have died at home. Alternatively, CVD events in patients who sought care or died at other hospitals may not have been registered in the HIV clinics in TAHOD due to a lack of data linkage between different healthcare facilities. However, since we captured fatal events using the standardized CoDe questionnaire, our outcome was likely to be specific. Therefore, the risk factors we identified significant in our analysis are expected to be truly associated with CVD [26]. Second, we could not evaluate the influence of specific antiretroviral drugs and inflammatory markers that have previously been associated with CVD [27, 28]. Furthermore, we did not assess the effect of co-medication or interventions that may have taken place during the observation period because this information is not collected as part of TAHOD. As with all observational studies, there might have been confounding of other factors that were not assessed in our study. Furthermore, there was a relatively high proportion of missing data on all cardiovascular risk factors and, as such, some of the effect may have remained undetected.

In summary, mortality in PLHIV in the Asia-Pacific region is still primarily caused by AIDS and to a lesser extent by non-communicable diseases such as CVD. However, with the aging of the Asian HIV-positive population CVD should remain firmly on the research and policy agenda. Our study showed that modifiable risk factors are important contributors to CVD in the Asia-Pacific region, highlighting the particular importance of regular monitoring and treatment of unfavourable CVD risk profiles in the clinical management of PLHIV. Our findings are similar to findings in other, more studied populations. Thus, lessons may be learned from efforts to improve CVD risk profiles that have proven successful in other settings.

Acknowledgements

PS Ly* and V Khol, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology & STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; FJ Zhang* ‡, HX Zhao and N Han, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; MP Lee*, PCK Li, W Lam and YT Chan, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China; N Kumarasamy*, S Saghayam and C Ezhilarasi, Chennai Antiviral Research and Treatment Clinical Research Site (CART CRS), YRGCARE Medical Centre, VHS, Chennai, India; S Pujari*, K Joshi, S Gaikwad and A Chitalikar, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India; TP Merati*, DN Wirawan and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia; E Yunihastuti*, D Imran and A Widhani, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia - Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; J Tanuma*, S Oka and T Nishijima, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; JY Choi*, Na S and JM Kim, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; BLH Sim*, YM Gani, and R David, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Sungai Buloh, Malaysia; A Kamarulzaman*, SF Syed Omar, S Ponnampalavanar and I Azwa, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; R Ditangco*, E Uy and R Bantique, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Muntinlupa City, Philippines; WW Wong* †, WW Ku and PC Wu, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; OT Ng*, PL Lim, LS Lee and PS Ohnmar, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; A Avihingsanon*, S Gatechompol, P Phanuphak and C Phadungphon, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; S Kiertiburanakul*, S Sungkanuparph, L Chumla and N Sanmeema, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; R Chaiwarith*, T Sirisanthana, W Kotarathititum and J Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai, Thailand; P Kantipong* and P Kambua, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand; KV Nguyen*, HV Bui, DTH Nguyen and DT Nguyen, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam; DD Cuong*, NV An and NT Luan, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam; AH Sohn*, JL Ross* and B Petersen, TREAT Asia, amfAR - The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand; DA Cooper, MG Law*, A Jiamsakul* and DC Boettiger, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia. * TAHOD Steering Committee member; † Steering Committee Chair; ‡ co-Chair

Funding

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, as part of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) [grant number: U01AI069907]. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above. The PhD of R Bijker has been supported through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet HIV 2017; 4: e349–e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballocca F, D’Ascenzo F, Gili S, Grosso Marra W, Gaita F. Cardiovascular disease in patients with HIV. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2017; 27: 558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin-Iguacel R, Llibre JM, Friis-Moller N. Risk of cardiovascular disease in an aging HIV population: where are we now? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015; 12: 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friis-Moller N, Ryom L, Smith C, et al. An updated prediction model of the global risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-positive persons: The Data-collection on Adverse Effects of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23: 214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. The Lancet 2014; 384: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Sex differences in overall and cause-specific mortality among HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Europe, Canada and the US. Antivir Ther 2015; 20: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen YF, Chen M, Jen I, et al. Association of HIV and opportunistic infections with incident stroke: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74: 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falster K, Choi JY, Donovan B, et al. AIDS-related and non-AIDS-related mortality in the Asia-Pacific region in the era of combination antiretroviral treatment. AIDS 2009; 23: 2323–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhr R, Kumarasamy N, Ly PS et al. HIV and aging: Demographic change in the Asia-Pacific region. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74: e146–e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezzati M, Riboli E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 954–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J Kumarasamy N Ditangco R et al. The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: Baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38: 174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD) Network. A decade of combination antiretroviral treatment in Asia: The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database Cohort. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32: 772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med 1999; 18: 695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the sub-distribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 446: 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti HIV drugs (D:A:D) Study Group. Factors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. AIDS 2010; 24: 1537–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz CM, Segura ER, Luz PM, et al. Traditional and HIV-specific risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected adults in Brazil: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nou E, Lo J, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Pathophysiology and management of cardiovascular disease in patients with HIV. The Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4: 598–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Socio GV, Pucci G, Baldelli F, Schillaci G. Observed versus predicted cardiovascular events and all-cause death in HIV infection: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petoumenos K, Reiss P, Ryom L, et al. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with age in HIV-positive men: a comparison of the D:A:D CVD risk equation and general population CVD risk equations. HIV Med 2014; 15: 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M et al. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 913–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helleberg M, May MT, Ingle SM, et al. Smoking and life expectancy among HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. AIDS 2015; 29: 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, et al. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan WA, Wirtz VJ, Stephens P. The market dynamics of generic medicines in the private sector of 19 low and middle income countries between 2001 and 2011: a descriptive time series analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8: e74399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. Second edition 2016 Geneva, CH: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore CL, Amin J, Gidding HF, Law MG. A new method for assessing how sensitivity and specificity of linkage studies affects estimation. PLoS One 2014; 9: e103690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bavinger C, Bendavid E, Niehaus K, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8: e59551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordell AD, McKenna M, Borges AH, et al. Severity of cardiovascular disease outcomes among patients with HIV is related to markers of inflammation and coagulation. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3: e000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]