Abstract

Tobacco consumption is a worldwide health problem threatening all, making no differentiation between gender, age, race, and cultural or educational background. Tobacco is responsible for 7 million deaths each year. Over 6 million deaths are directly related to tobacco consumption, and over 890.000 deaths involve non-smokers exposed to tobacco smoke. Although the harmful effects of cigarettes on human health have been confirmed repeatedly, still over 1 billion people worldwide are tobacco consumers, and according the World Health Organization (WHO), unless a strict action plan is implemented, tobacco-related deaths will rise to more than 8 million per year by 2030. The WHO published the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003, which could form a common policy to guide countries in the struggle against tobacco. Tobacco control in the Convention is defined as “a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke.” This agreement was adopted by Turkey in 2004 with the Law No. 5261. In 2008, the WHO published the MPOWER package, containing the following six basic strategies, which are parallel with the Tobacco Framework Convention measures and practices:

Monitor tobacco use.

Protect people from tobacco smoke.

Offer help to quit tobacco use.

Warn about the dangers of tobacco.

Enforce bans on tobacco advertising and promotion.

Raise taxes on tobacco products.

In the 2013 Global Tobacco Control Report by the WHO, Turkey was announced as the first country achieving a high level of success in the six MPOWER strategies, and other countries were advised to adopt the Turkish policies. Here we review Turkey’s MPOWER tobacco control strategies one by one.

Keywords: Tobacco, MPOWER, Turkey, control policies, public health

Introduction

Tobacco consumption is a worldwide health problem threatening all, making no differentiation between gender, age, race, and cultural or educational background. Tobacco is responsible for 7 million deaths each year. Over 6 million of these deaths are directly related to tobacco consumption, and over 890 000 deaths, on the other hand, involve non-smokers exposed to tobacco smoke [1]. In the tobacco smoke, there are more than 4,000 chemicals, out of which at least 250 confirmed as harmful and more than 50 causing cancer [1]. Aziz Sancar and his team have developed a special method for the genetic mapping of the DNA damage caused by a major chemical carcinogen (benzo[α]pyrene—BaP), a side product of burning organic materials such as the tobacco plant. This technique is demonstrating the evidence that tobacco products are adversely affecting the human DNA [2]. Although the knowledge on harmful effects of cigarettes on human health have been confirmed repeatedly, still more than 1 billion people worldwide are tobacco consumers and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), unless a strict action plan is implemented, tobacco-related deaths will rise to more than 8 million per year by 2030 [1].

The WHO published the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003, which could form a common policy to guide countries in the struggle against tobacco [3]. Tobacco control in the Convention is defined as “a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke” [3]. This agreement was adopted by Turkey in 2004 with the Law No. 5261[4]. In 2008, the WHO published the MPOWER package containing the following six basic strategies, which are in parallel with the measures and practices in the Tobacco Framework Convention [5]:

Monitor tobacco use.

Protect people from tobacco smoke.

Offer help to quit tobacco use.

Warn about the dangers of tobacco.

Enforce bans on tobacco advertising and promotion.

Raise taxes on tobacco products.

Anti-tobacco Laws and Regulations in Turkey

In Turkey, the government-initiated serious anti-tobacco activities do not date far back. The first tobacco control law was adopted in 1996 by the Law No. 4207 on the Prevention of Harmful Effects of Tobacco Products [6]. In 2008, the first law was amended, and the second tobacco control law was adopted by Law No. 5727 on the Prevention and Control of the Harms of Tobacco Products [7].

In Article I, the purpose of the Law No. 4207 was expressed as “to take preventive arrangements and measures for protecting people and next generations from harmful effects of tobacco products, as well as advertising and promotion campaigns encouraging their use, and to ensure that everyone is able of breathing clean air” [6]. Accordingly, the places where tobacco products can be consumed were restricted, the rules for the protection of non-smokers were laid down; prohibited places for tobacco consumption were defined; advertisements and promotions to promote tobacco use were prohibited; regulations for the reduction of tobacco use were put in place; and relevant penalties were laid down in the Code of Misdemeanors for unlawful behaviors [6].

The Ministry of Health of Turkey has prepared in 2006 a National Tobacco Control Program within the scope of the “Framework Convention on Tobacco Control” aiming to curb cigarette consumption [8]. Provincial Tobacco Control Boards were established in 2007 to carry out the coordination and follow-up of the implementation of the National Tobacco Control Program and the fulfillment of the duties of the plan, as well as supervise the control activities against the harms of tobacco and tobacco products [9]. Turkey’s first “National Tobacco Control Program” was implemented in 2008–2012 [10].

Smoking Prevalence in Turkey

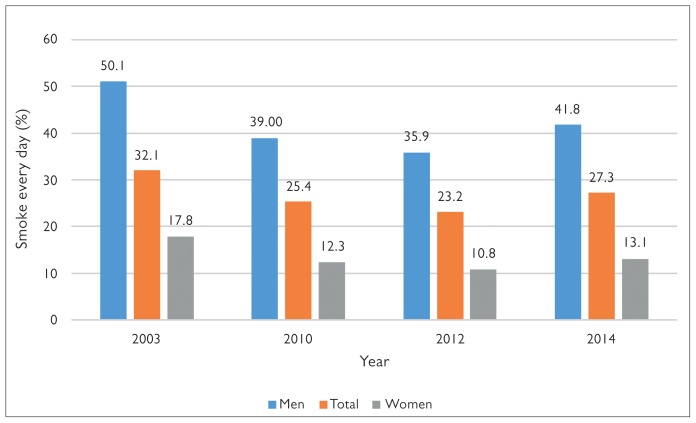

The prevalence of tobacco use in Turkey, according to the Global Adult Tobacco Surveys in 2008 and 2012, has dropped to 27.1% from 31.2% (in males from 47.9% to 41.5%, in females from 15.2% to 3.1% ) [11]. These rates are demonstrating the success of the program. However, if we look from a broader perspective, there is a decrease between the years 2003 and 2012 followed by a resurge in 2014 (Figure 1) [12].

Figure 1.

Trends in tobacco use in Turkey

The “National Tobacco Control Program Action Plan 2015–2018” was prepared as a response to this increase [13]. In accordance with the new action plan, the Tobacco Control Practices Circular has been issued, initiating the work toward the application of the regulation also in open areas [14]. According to the Turkish Statistics Institute (TUIK) 2016 health survey, the proportion of tobacco users aged 15 and over was 32.5% in 2014, which dropped to 30.6% in 2016 [15].

Responses of the Tobacco Industry

A new tactics developed by the tobacco industry and their way of work make the control much tougher [16]. The tobacco report of 1964 is important in terms of proving the health-related harms of tobacco use, which was claimed to be beneficial to human health back then [17]. Today, including tobacco users, people know that tobacco is harmful. In response to the adoption of this information by the society, the tobacco industry has sought new markets instead of reducing tobacco products and has recently moved into the fast-paced market of electronic cigarettes and heated cigarettes. Also, the import of these new tobacco products is prohibited in Turkey [18]. The fight against tobacco is a challenging act, requiring a strength of purpose, and the struggle against tobacco has been active in Turkey for many years.

Turkey’s MPOWER Success

In the 2013 Global Tobacco Control Report by the WHO, Turkey was announced as the first country achieving a high level of success in the six MPOWER strategies, and other countries were advised to adopt the Turkish strategies [19]. In the Global Tobacco Control Report 2015 country profiles, Turkey was again mentioned as meeting all the criteria [20].

Let us review Turkey’s MPOWER tobacco control strategies one by one:

1. Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies

Tobacco use is monitored, and prevention policies are developed by the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority, TUIK, and the Turkey Demographic and Health Survey [21–24].

In a study conducted in 1998, which examined the frequency of tobacco use among adults in Turkey, the prevalence of smoking was found to be 43.6% [25]. Later, especially after the year 2000, statistical monitoring was carried out every 2–3 years. The same year, smoking prevalence was found at 58.8% in Erzurum, demonstrating higher rates in the eastern regions of Turkey [26]. Generally speaking, 1 out of every 2 people in the country in 1988 was a tobacco user, while in 2016, 1 of every 3 people consumed tobacco products.

In addition to the number of consumers, of equal importance consuming tobacco products are the characteristics of the group consuming these products. In the Law No. 4207, it is stated that tobacco products and similar products with or without tobacco, such as narghile, will not be sold to people who are under 18 years and will not be offered for consumption [6]. Despite this article of the law to protect those at the age of 18 and younger, the health survey in 2014 demonstrated that 4.5% of tobacco users initiated consumption younger than 10, and almost half (47.8%) of all consumers implemented consumption between the ages of 15 and 19 [12].

Local studies from various regions of Turkey also give ideas about the tobacco policy. According to the study conducted by Doruk et al. [27] in Tokat province in 2009, 84.4% of the workers had information about the law, while only 64.7% of them were aware of the penalty for not obeying the law [25]. Knowing the penalty of not complying with the law and making arrangements according to the law is higher in large enterprises compared with small businesses [27]. Özcebe et al. [28] conducted a study in 27 tea houses in Ankara and found that half of the cigarette smokers considered quitting smoking and that 45.8% decreased usage after implementation of the law.

In the survey conducted by Türkkanı et al. [29] in Çorum in 2010, 83.3% of the health personnel who were active cigarette users stated that their reaction about the smoking ban in closed places was positive. Aydın et al. [30] found in Gaziantep in 2009 that 80.4% of the teachers were supporting the law prohibiting smoking in closed areas. In these two surveys conducted among teachers and health workers, it is observed that 1 out of 5 people did not give a positive opinion. It may be useful to organize individualized training for them to make these two professional groups more conscious, which may influence the community behavior and become collective role models. In the study conducted by Bilir et al. [31] in Ankara, 55.2% of surveyed taxi drivers supported the ban on smoking in taxis, whereas 33.2% stated that they were against this prohibition. In the same study, breath carbon monoxide levels were found to be 8% or more in almost all smokers (96.5%), while non-smoker drivers had no levels higher than 7, and it was determined that cigarettes were smoked in 59 out of the 900 (6.6%) observed taxis.

According to the study of Dağlı et al. [32] in Istanbul conducted in 5 hospitals, after the law restricting smoking in closed areas, emergency service applications due to cardiovascular and acute respiratory diseases have been found to be reduced between 16% and 33.6%.

2. Protect people from tobacco smoke

In Turkey, a campaign is conducted under the name “Smokeless Airspace” to prevent passive smoking [33]. To prevent the passive effects of cigarette smoke, the concept of closed space was extended via amendments in the Law No. 4207. As of July 19, 2009, according to the new definition of the closed area in the law, “Closed areas are places with fixed or movable ceilings or roofs (including tents, blinds, etc.), having all side surfaces permanently or temporarily closed except for doors, windows, and access ways, or in the same manner, having a roof or ceiling with side surfaces halfway closed” [34].

In the study conducted by Bilir and Ozcebe, before and after the implementation of the law, they measured particles (PM2.5) and evaluated the air quality of closed areas in 8 different cities, where they found on average a 22.9% decrease in particles in workplaces after the law got into action [35]. According to the global adult tobacco survey data, in 2012, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of passive exposure to cigarette smoke in all public indoor areas compared to 2008; the most significant decrease was observed in restaurants (55.9% in 2008 and 12.9% in 2012) [11].

After the implementation of the law about the indoor areas, the Tobacco Control Practices Circular was issued in 2015 for the implementation of the National Tobacco Control Program Action Plan 2015–1018 [14]. According to the circular, the use of tobacco and tobacco products has been restricted to at least 5-meter distance from the entrance doors of the places defined as closed areas used heavily and collectively by people, such as airports, bus terminals, train stations, shopping centers, cinemas, theaters, health institutions; for government organizations with designated smoking areas, which do not have more than 30% of open areas, at least 10 meters from the entrance door; in all public places used by children; walking paths; and public exercise areas established by institutions [14].

3. Offer help to quit tobacco use

Across Turkey as of 2017, there are 303 registered smoking cessation clinics for one to be referred via the “Hello 171” line [36]. Balbay et al. [37] found the smoking cessation rate at 22.4% during 6 months of follow-up in the Düzce Medical Faculty smoking cessation outpatient clinics in 2001. In the retrospective study conducted by Tezcan et al. [38] in two smoking cessation policlinics in Konya in 2009, all of the cases quit smoking within the first 15 days, and 64% did not resume smoking at the 1-year follow-up. As for the study done by Mutlu et al. [39] in 2012 conducted in smoking cessation policlinics of state hospitals, the smoking cessation rates at the 6th month were found to be 32.3%. The abstinence rates of 52.8% were found in patients receiving nicotine replacement therapy [40].

The Ministry of Health established a Smoking Cessation Advice Line (Hello 171) operating on a 7/24 basis, which provides consultancy services to those who want to quit smoking. According to January 2018 data, a total of 35,153 people participated in the smoking cessation support program [41].

4. Warn about the dangers of tobacco

According to the Law No. 4207 in Turkey, Turkish Radio and Television Corporation and national, regional, and local broadcasting private television and radio stations have to broadcast between 08:00 and 22:00 (at least 30 minutes at prime-time, 17:00–22:00, and at least 90 minutes per month in total) stimulating and educating programs on tobacco products and other harmful habits [34].

It is compulsory that all tobacco products produced in Turkey or imported to Turkey have to include written warning messages in Turkish, mentioning the harms of tobacco products, included at two widest sides of the product, on one side of the product covering at least 40% of the surface, and on the other side at least 30% within a special frame, and the same warning is to also be included on the main packing for products containing more than one pack. Import and sale of products that do not carry warning messages are prohibited [34].

5. Enforce bans on tobacco advertising and promotion

As to Law No. 4207, it is forbidden in Turkey to include tobacco products and manufacturers’ names in advertising and promotions using the logo or trademark, organizing campaigns that encourage or promote the use of these products, or support any activity using the logo or product brand [34].

In the National Tobacco Control Program Action Plan 2015–2018, it was also mentioned that necessary legislative amendments should be made on the uniform plain package implementation [13].

6. Raise taxes on tobacco products

The no. 4760 Special Consumption Tax Law, aiming at taxation in some private consumption expenditures entered into force on February 12, 2002. The Special Consumption Tax (SCT) is taken from the goods listed in the four lists attached to the Law No. 4760. Tobacco products are listed under number III [42].

Changes in the SCT rates have been aimed at reducing the consumption of tobacco products. When the cigarette consumption was examined in terms of the changes made in the SCT, with the decision of the Council of Ministers issued in 2005, the relative SCT of cigarettes having increased from 28% to 58% resulted in a decrease in the consumption of cigarettes by approximately 2.15 billion. It was observed that the consumption increased again in the following years, but it did not return to its former levels. Similar results were obtained with the SCT changes in 2009, 2011, and 2013 [43].

In the National Tobacco Control Program Action Plan 2015–2018, it was decided that the SCT amounts shall be integrated into the changes within the last 6 months of the producer price index announced by the Turkey Statistical Institute in January and July [13].

Conclusion

It is a reality that Turkey has achieved successful developments in the ongoing struggle with tobacco that lasted for more than 20 years. However, despite the decrease in tobacco consumption rates, smoking prevalence is still high. As to the decline in 2016, the new action plan seems to be successful. However, the fact that the ratio is still above the 2012 figures makes it necessary to initiate a more extensive examination of the issue. Failure to achieve the desired decrease may be due to reasons such as the development of an immunity against tobacco restrictions by the tobacco users or companies, or the failure to implement the restrictions. This suggests that the interventions made should be effective and in a way that does not allow for a recession, and always be one step ahead of the factors that could increase tobacco consumption.

There are two main elements in the tobacco fight: reduction of tobacco use in the society and protection of non-tobacco users. In addition, two basic strategies are needed to reduce tobacco use in the society: The first is to quit cigarette smoking, the most common form of tobacco use, and the second, and more important, is to prevent the implementation of smoking. Given that tobacco is an addictive substance, avoiding the implementation will be much more efficient and less costly than terminating dependence. Given that half of the cigarette consumers start to smoke between the ages of 15 and 19 years, it can be predicted that the work to be done for this group can dramatically reduce the smoking rate in the country. In that case, protecting young people (the main target group of the tobacco industry) should be the basic principle of dealing with the tobacco problem. To achieve this, starting from early ages, the harms of the cigarettes must be explained, and children and young people should be provided with health consciousness. In addition, it may be useful to arrange smoking cessation units in the family health centers, which everyone can easily access, as well as having tobacco cessation polyclinics in health institutions, and to have competent and certified health personnel in each primary health care center. It is important to maintain and improve all tobacco cessation clinics that demonstrated positive achievements in the tobacco struggle. Again, all statutory audits and criminal proceedings to prevent passive smoking and illegal access to tobacco should be applied with determination. All kinds of interventions that can weaken the powers of the inspections should be prevented, and the implementation of criminal proceedings should not be deficient. If every segment of the society is trained in combating tobacco, if a general health awareness is established, and if the health literacy level of the society is raised, much easier and faster developments in the fight against tobacco will be possible.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the surveyors for their time and interest. We are also grateful to everyone stating idea and offering suggestions during the study period.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – E.O.C., E.K. ; Design – E.O.C., E.K. ; Supervision - E.O.C., E.K. ; Resources – E.O.C., E.K. ; Materials – ; Data Collection and/or Processing - E.O.C., E.K. ; Analysis and/or Interpretation – E.O.C., E.K.; Literature Search – E.O.C., E.K. ; Writing Manuscript –E.O.C., E.K., ; Critical Review – E.O.C., E.K.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Tobacco Fact Sheet. Updated May 2017 (cited 2017 November 3). Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

- 2.Map of DNA damage caused by tobacco. (cited 2018 January 2). Available from: URL: http://www.havanikoru.org.tr/component/k2/298/prof-dr-aziz-sancar-dansigaranin-dna-ya-verdigi-hasarin-haritasi.html.

- 3.World Health Organization. Occupational Health. (cited 2017 December 29). Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/topics/occupational_health/en/

- 4.Decision on the Approval of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Official Gazette dated 25 December 2004 and numbered 25681. (cited 2018 January 09); Available from: URL: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2004/12/20041225.htm

- 5.World Health Organization. MPOWER: Six policies to reverse the tobacco epidemic. 2008. Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_report_six_policies_2008.pdf.

- 6.Law on the Prevention of Hazards to Tobacco Product. 1996. Official Gazette dated 26 November 1996 and numbered 22829

- 7.Law on the Amendment of the Law on the Prevention of Hazards to Tobacco Products. 2008. Official Gazette dated 19 January 2008 and numbered 26761

- 8.Circular on National Tobacco Control Program. 2006. Official Gazette dated 7 October 2006 and numbered 26312

- 9.Circular on Establishment of Tobacco Control Board in Provinces. 2007. Official Gazette dated 24 May 2007 and numbered 11083

- 10.TR Ministry of Health. National Tobacco Control Program and Action Plan. 2008. (cited 2017 May 31) Available from: https://sbu.saglik.gov.tr/Ekutuphane/kitaplar/t15.pdf.

- 11.TR Ministry of Health. Global Adult Tobacco Research to Turkey in 2012. (cited 2017 June 7). Available from: URL: http://www.halksagligiens.hacettepe.edu.tr/KYTA_TR.pdf.

- 12.TR Ministry of Health. Health statistics yearbook. 2015. pp. 47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Tobacco Control Program Action Plan (2015–2018) Circular No. 2015/1 issued by the Official Gazette dated January 27, 2015 and numbered 29249. 2015

- 14.Circular on Tobacco Control Practices Circular 2015/6, No: 86696344/010.06. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turkey Statistical Institute. Turkey in Statistics. 2016. Available from: URL: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7330775/7339623/Turkey+_in_statistics_2015.pdf/317c6386-e51c-45de-85b0-ff671e3760f8.

- 16.Elbek O, Kılınç O, Aytemur ZA, et al. Tobacco control in Turkey. Turk Thorac J. 2015;16:141–50. doi: 10.5152/ttd.2014.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The 1964 Report on Smoking and Health. 1964. The Reports of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Answer to the written question number 86696344-610. The Grand National Assembly of Turkey; (cited 2018 January 3) Available from: URL: http://www2.tbmm.gov.tr/d24/7/7-19613sgc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization, WHO. Report On The Global Tobacco Epidemic. 2013. Available from: URL: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85380/9789241505871_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7FD9FE77C33463D38DCA4668D70821ED?sequence=1.

- 20.World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. 2015. Available from: URL: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/178574/9789240694606_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 21.TR Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulator. Turkish Tobacco Products Statistics. (cited 2017 May 4). Available from: URL: http://www.tapdk.gov.tr/tr/piyasa-duzenlemeleri/tutun-mamulleripiyasasi/tutun-mamulleri-istatistikleri.aspx.

- 22.Turkey Statistical Institute. Global Adult Tobacco Use Statistics. 2017. (cited 2017 May 4). Available from: URL: http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1042.

- 23.TR Ministry of Health. Turkey statistical yearbook. (cited 2017 May 4). Available from: URL: https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,11588/istatistik-yilliklari.html.

- 24.Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies. Turkey’s population and health survey. p. 2013. (cited 2017 May 4). Available from: URL: http://www.hips.hacettepe.edu.tr/tnsa2013/rapor/TNSA_2013_ana_rapor.pdf.

- 25.Anti-Smoking Campaign Opinion Survey. PIAR Research Co. Ltd; Şti. Turkey: Jan, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saglam L, Kaynar H, Görgüner M, Mirici A. Erzurum İlinde sigara içme alışkanlığının araştırılması. Solunum Dergisi. 2000;11:148–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doruk S, Çelik D, Etikan I, İnönü H, Yilmaz A, Seyfi Z. Evaluation of the knowledge and attitudes of business people regarding the prohibition of smoking in closed areas in Tokat. Tuberk Toraks. 2010;58:286–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Özcebe H, Bicer BK, Evran AÇ, Matola BW, Kiraz S, Kaplan HG. Feedback from Turkey’s Comprehensive Tobacco Control Act Two Years After coffee shop Customer (Ankara, 2011) Turk Toraks Derg. 2013;14:11–8. doi: 10.5152/ttd.2013.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Türkkanı MH, Aydın LY, Özdemir T. Changes in Smoking Habits in Health Care Workers Smoking Cessation Law “Prevention and Control of Tobacco Product Losses”. Eurasian J Pulmonol. 2014;16:175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aydin N, Uyar M, Kul S, Elbek O. Awareness of Teachers about Law No. 4207. Turk Silahlı Kuvvetleri Koruyucu Hekim Bul. 2011;10:543–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilir N, Yardım MS, Sığık M, Arpat O, Atalay Y, Aydoğan B. Assessment of Attitudes and Behaviours of Taxi-Drivers in Ankara on the Smoking Ban in Cabs. Turk Toraks Derg. 2012;13:141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dağlı E, Erdem E, Birinci Ş, et al. The impact of smoking ban on emergency department admissions in Istanbul for the diseases associated with tobacco usage and passive smoking. 14th Annual Congress of the Turkish Thoracic Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Protect the air. Smokeless airspace. (cited 2018 January 3). Available from: URL: http://www.havanikoru.org.tr/

- 34.Implementation guidance on the provisions of the law on the prevention and control of damage to tobacco products numbered 4207

- 35.Bilir N, Özcebe H. The influence of the prohibition of smoking in indoor environment on indoor air quality. Tuberk Toraks. 2012;60:41–6. doi: 10.5578/tt.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smoking Cessation Polyclinics. [cited 2017 August 17]; Available from: https://alo171.saglik.gov.tr/?/poliklinikler.

- 37.Balbay Ö, Annakkaya AN, Aytar G, Bilgin C. The results of the chest diseases smoking cessation polyclinic of Düzce Medical Faculty. Düzce Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi. 2003;3:10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tezcan B, Öncel M, Sunam GS. Patients Seeking Help from Smoking Cessation Clinic: One-Year Follow-up. Cukurova Medical Journal (Cukurova University Faculty of Medicine Journal) 2012;37:103–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mutlu P, Yıldırım BB, Açık B. Results Taken from a Smoking Cessation Clinic at a Second-Level State Hospital. Istanbul Med J. 2015;16:145–8. doi: 10.5152/imj.2015.67934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yilmazel Ucar E, Araz O, Yilmaz N, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacologic therapies on smoking cessation success: three years results of a smoking cessation clinic. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2014;9:9. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smoking cessation advice line ALO 171. (cited 2018 January 9). Available from: URL: https://alo171.saglik.gov.tr/?/default.

- 42.Private Consumption Tax Law. Official Gazette dated June 12, 2002 and numbered 24783

- 43.Hayrullahoğlu B. Türkiye’de Tütün Mamulleri Ve Alkollü İçkilerde Özel Tüketim Vergisinin Başarısı. Journal of Life Economics. 2015;2:89–112. doi: 10.15637/jlecon.72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]