Abstract

Ruminative response style is a passive and repetitive way of responding to stress, associated with several disorders. Although twin and candidate gene studies have proven the genetic underpinnings of rumination, no genome-wide association study (GWAS) has been conducted yet. We performed a GWAS on ruminative response style and its two subtypes, brooding and reflection, among 1758 European adults recruited in the general population of Budapest, Hungary, and Manchester, United Kingdom. We evaluated single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based, gene-based and gene set-based tests, together with inferences on genes regulated by our most significant SNPs. While no genome-wide significant hit emerged at the SNP level, the association of rumination survived correction for multiple testing with KCTD12 at the gene level, and with the set of genes binding miR-383 at the gene set level. SNP-level results were concordant between the Budapest and Manchester subsamples for all three rumination phenotypes. SNP-level results and their links to brain expression levels based on external databases supported the role of KCTD12, SRGAP3, and SETD5 in rumination, CDH12 in brooding, and DPYSL5, MAPRE3, KCNK3, ATXN7L3B, and TPH2 in reflection, among others. The relatively low sample size is a limitation of our study. Results of the first GWAS on rumination identified genes previously implicated in psychiatric disorders underscoring the transdiagnostic nature of rumination, and pointed to the possible role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum in this cognitive process.

Introduction

Ruminative response style refers to a trait-like tendency to reflect in a passive and repetitive way on personal feelings and difficulties1,2, being thus a manifestation of cognitive inflexibility and perseveration that prolongs the individual’s reaction to stress3,4. High scores on questionnaire measures of rumination are associated with increased risk of various mental disorders, including major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia1, and with symptoms of alcohol abuse5, binge eating6, generalized anxiety1, and migraine7. By prolonging stress reaction it is thought to adversely affect cardiovascular and immune responses as well as numerous somatic complaints, such as pain3,4.

On the basis of factor analytic studies of questionnaire scales, Treynor et al.8 identified two subtypes of rumination: brooding, which denotes a maladaptive mechanism of passively comparing one’s current situation with an unachieved standard; and reflection which indicates a more adaptive strategy of purposefully turning inward for cognitive problem solving. According to twin studies among adolescents, rumination score has a 24% heritability9, ranging from 21% in case of the brooding to 37% in case of the reflection subtype10. However, in twin studies among young adults heritability of rumination is even higher, ranging from 34% for females to 40% for males11.

Candidate gene studies have revealed replicable associations with rumination. Three studies reported that the 5-HTTLPR functional length polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 promoter significantly interacts with life stress to increase rumination scores12–14. We demonstrated that the effect of the serotonin receptor 2A gene HTR2A on brooding is a function of childhood adversity15. Another study showed that the glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone FKBP5 gene interacts with attachment security to affect rumination scores in children16, and with childhood trauma to affect rumination in adolescents17. Our recent results have identified the MTHFD1L gene in the folate metabolism as a risk variant for rumination18. Furthermore, a gene–gene interaction effect on rumination has been reported for G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunit 2 (GIRK2) gene KCNJ6 and cAMP-response element binding protein gene CREB1, pointing to the importance of synaptic plasticity in the generation of rumination19. Association of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene BDNF and rumination20–22 also points to this direction, although controversial results are available regarding rumination in adults14,20,23 and in children22. Despite its potential mediatory role in various disorders and the promising results of candidate gene studies, no genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have yet been reported for rumination.

In the present study, we performed a GWAS on rumination and its two subtypes, brooding and reflection, in a European general population to explore genetic risk variants and pathways that contribute to this cognitive phenotype.

Methods

Participants

This study was part of the NewMood study (New Molecules in Mood Disorders, Sixth Framework Program of the EU, LSHM-CT-2004-503474) and was funded by the European Union. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and were approved by the North Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee, Manchester, United Kingdom, and by the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Council, Budapest, Hungary. Participants aged between 18–60 years were recruited through advertisements, general practices, and a website in Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, and through advertisements and general practices in Budapest, Hungary. All of them provided a written informed consent, and all of them were of European white ethnic origin.

Phenotype

Participants filled out the NewMood questionnaire pack, comprising the 10-item Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS)8, and a background questionnaire asking about gender, age, ethnicity, lifetime psychiatric problems, and present somatic disorders, relevant to rumination. RRS has two subscales, representing the two subtypes of rumination: brooding and reflection. We calculated the score for rumination, brooding and reflection as a continuous weighted score: the sum of item scores divided by the number of completed items.

Genotyping, quality control, and imputation

Participants provided DNA by a genetic saliva sampling kit. Genomic DNA was extracted from buccal mucosa cells according to established protocols24. Genotyping was performed using Illumina's CoreExom PsychChip yielding a total of 573 141 variants, the genomic positions of which were defined according to the build GRCh37/hg19. Quality control and imputation was based on ref. 25, see also Supplementary File 1.

Analyses

For descriptive statistics we used SPSS 25.

Our sample size greater than 200 enabled us to use parametric statistical methods, irrespectively of normality of distributions26.

To assess variance in each of the three examined traits explained by all single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in our dataset we used the genomic-relationship-matrix restricted maximum likelihood (GREML) method in the genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) software, version 1.26.0 (ref. 27). In the analysis of rumination, covariates were gender, age, and the first 10 calculated principal components (PCs) of the genetic data to correct for population substructure. In case of each subscale, the other subscale was also included as a further covariate, to eliminate their shared variance.

Primary SNP-based association tests for each phenotype were calculated using linear regression models in Plink 1.9 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2), assuming an additive genetic effect. All models contained the covariates described above for the GCTA analyses.

To test the consistency and reproducibility of the above SNP-based association results between the Budapest and Manchester subsamples, sign tests were performed. First, SNPs were filtered in the combined Budapest + Manchester dataset by their p-values using a given threshold (p < 0.05, p < 1 × 10–3, and p < 1 × 10–5, respectively), based on refs. 28,29, and by their linkage disequilibrium (R2 ≥ 0.5) with the most significant SNP retained. For these remaining relevant and approximately independent SNPs, sign of the linear regression coefficients (betas) was compared between the Budapest and Manchester datasets. Rate of concordance with a 95% confidence interval and the p-value of the corresponding right-tailed sign test were calculated.

To carry all SNP-based associations to further levels, enrichment analysis was conducted both for individual genes and for gene sets. Gene-based annotations for SNPs were defined according to the RefGene database, build hg19, with an extension of 10,000 base pairs in both ends30. Gene sets were defined according to version 6.1 of MSigDB (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/), we examined sets defined in collections C5 (Gene Ontology—GO—terms, all categories), C3.mir (microRNA targets), and C3.tft (transcription factor targets). Gene sets were restricted to those containing at least 15 genes and no more than 300.

To aggregate p-values at the level of SNPs to the level of genes, the following methods were applied: (i) uncorrected minimal p-value within; (ii) minimal p-value adjusted according to Sidak's method; (iii) Fisher's method of combining correlated p-values modified according to Makambi31, and Kost and McDermott32; (iv) fixed-effect z-score statistics (http://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2015/07/31/023648.full.pdf); also (v) a slightly modified version of Makambi's method (as implemented by the ‘--set-screen’ option of Plink); and (vi) the method described in ref. 33. These methods were also applied to sets of genes analogously treating the corresponding SNPs.

Furthermore, the effective chi-squared (ECS) and Gates34 methods (implemented by the software KGG 4.035; version released on 8 September 2018) were also applied at the gene level, and, based on gene-level results of Gates, Wilcoxon and hybrid set-based test (HYST) methods (also implemented by KGG 4.0) were applied to derive results at the gene set level.

To further aggregate the above eight p-values (both at the gene and at the gene set level), the rank-averaging method described by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium36 was applied in the permutation testing framework to yield a single (“empirical”) p-value and false discovery rate (FDR) q-value for each gene and gene set (with one million permutations). As in ref. 36, we consider the genes and gene sets with a q < 0.1 as significant.

To explore the known functional effects of our most significant SNPs as reported by public open databases, based on expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and 3D chromatin interaction, we used FUMA v1.3.1 (ref. 37), with a p ≤ 1x10–5 threshold for lead SNPs, an R2 ≥ 0.5 to define a genomic risk locus around a lead SNP, and a p ≤ 0.05 to involve SNPs into it. Each SNP of the genomic risk loci (referred to as top SNPs or our most significant SNPs) were mapped to a gene if either residing within gene boundaries extended by 10,000 base pairs, or having an FDR q ≤ 0.05 with it in the external eQTL, or a q ≤ 1 × 10–6 with its promoter region in the external chromatin interaction dataset37.

Results

Sample characteristics

After imputation and quality control steps, we had 3,474,641 SNPs and 1758 subjects (773 from Budapest and 985 from Manchester) with data on rumination, gender, age, and ten PCs of the genome. The number of SNPs entailed a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of p ≤ 1.44 × 10–8, and, at the SNP level, we considered p ≤ 1 × 10–5 a threshold for suggestive significance. Entering all SNPs into gene-based and gene set-based tests, our analyses yielded 25,371 genes, 4323 C5 gene sets, 182 C3 microRNA target (MIR) gene sets, and 550 C3 transcription factor target (TFT) gene sets.

Regarding descriptive statistics on rumination, gender, age, lifetime psychiatric problems, and present somatic disorders, Supplementary Table 1 shows that except for frequency of pain problems there are differences between the Budapest and Manchester subsamples in all variables at either a nominally significant (p ≤ 0.05) or trend (0.05 < p ≤ 0.10) level. The brooding and reflection subscales had a Pearson correlation of r = 0.488 (p < 0.00001) with each other in the combined sample, r = 0.373 (p < 0.00001) in Budapest, and r = 0.507 (p < 0.00001) in Manchester, underpinning the necessity of including the other subscale as a covariate when analyzing the specific variability of a subscale.

SNPs in the background of rumination, brooding, and reflection

Before testing the role of particular SNPs in rumination, brooding, and reflection, we applied the GREML method to investigate the polygenic nature of these phenotypes, namely proportion of their variance residing in the whole set of the investigated SNPs, with results displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of the GREML analysis for each phenotype and estimated SNP heritability

| Rumination | Brooding | Reflection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variance | |||

| Value | 0.294 | 0.325 | 0.324 |

| Standard error of value | 0.0100 | 0.0110 | 0.0110 |

| Variance explained by SNPs | |||

| Value | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.032 |

| Standard error of value | 0.0406 | 0.0397 | 0.0430 |

| SNP heritability | |||

| Value | 0.105 | 0.107 | 0.099 |

| Standard error of value | 0.1380 | 0.1219 | 0.1328 |

| P-value | 0.230 | 0.164 | 0.226 |

GREML genomic-relationship-matrix restricted maximum likelihood method, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, p-value p-value of the respective model

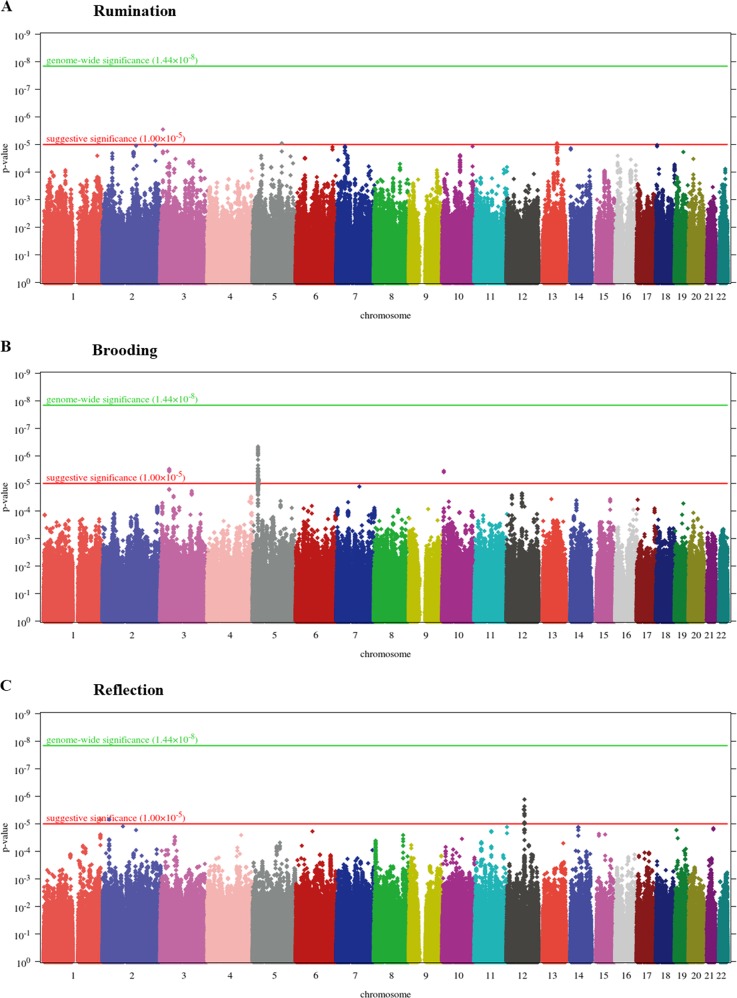

With respect to particular SNPs, for rumination SNP-based association tests yielded a genomic inflation factor of λ = 1.00984. For the quantile-quantile (QQ) plot, see Supplementary Figure 1. No SNP survived Bonferroni correction for multiple testing but 3 SNPs had a suggestive significance which either reside in LMCD1 or are intergenic (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1. Manhattan plots of genome-wide SNP-based tests for rumination (a), brooding (b), and reflection (c) as outcome.

P-value is displayed in function of genomic position for each single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). The red and green lines denote the levels of a suggestive and a genome-wide significance, respectively

In case of brooding, lambda value of the genome-wide SNP-based tests (for the QQ plot, see Supplementary Figure 2) was 1.00124. No SNP survived correction for multiple testing; however, we had 59 SNPs with suggestive significance (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 3). These SNPs are mapped to the CDH12 (Fig. 2b), STAC, and RBM17 genes.

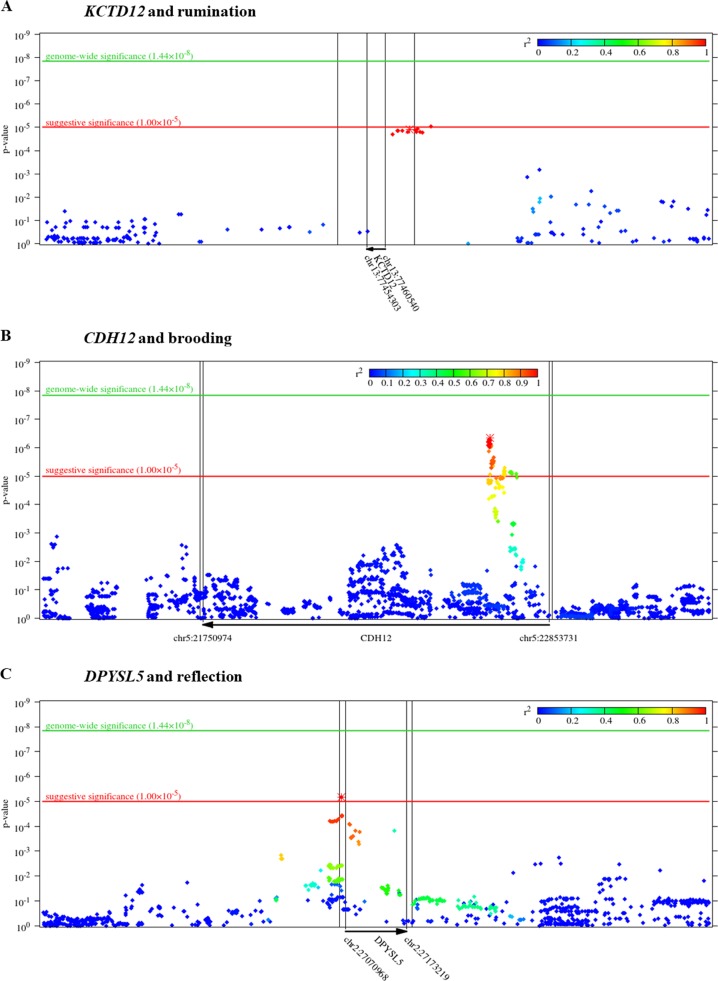

Fig. 2. Zoomed Manhattan plots of KCTD12 gene for rumination (a), CDH12 gene for brooding (b), and DPYSL5 gene for reflection (c) as outcome.

P-value is displayed in function of genomic position for each single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the region. Colors denote the r2 value of linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the most significant SNP (marked with asterisk). Gene boundaries and their extension by 10,000 base pairs (as defined for the gene-based tests) are marked with vertical lines

Regarding reflection, according to the SNP-based tests, λ = 1. For the QQ plot, see Supplementary Figure 3. No SNP survived correction for multiple testing but we had 28 suggestively significant SNPs (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 4). Most of these 28 SNPs are intergenic within the chromosomal region of 12q21.1 (Supplementary Figure 4) but some of them reside in DPYSL5 (Fig. 2c) or CHRM3.

Results of the sign tests on the reproducibility of SNP-based results between the Budapest and Manchester subsamples are displayed in Table 2 for all three phenotypes. We can see that the direction of effect of the independent lead SNPs was significantly concordant between the separate subsamples, except in case of the most stringent p-value threshold, which yields an inclusion of only one or two SNPs with a 100% but insignificant concordance.

Table 2.

Results of sign tests on concordance of the independent lead SNPs between the Budapest and Manchester subsamples

| P-value threshold for SNP inclusion | Rumination | Brooding | Reflection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | Percentage of concordant SNPs (95% CI) | 91.866% (91.413–92.302%) of 14,777 SNPs | 93.687% (93.283–94.073%) of 14,826 SNPs | 93.945% (93.551–94.323%) of 14,931 SNPs |

| P-value of the sign test | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | |

| 1 ×10–3 | Percentage of concordant SNPs (95% CI) | 96.783% (94.448–98.327%) of 373 SNPs | 96.296% (93.750–98.013%) of 351 SNPs | 97.778% (95.668–99.036%) of 360 SNPs |

| P-value of the sign test | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | |

| 1 ×10–5 | Percentage of concordant SNPs (95% CI) | 100% (2.500−100%) of 1 SNP | 100% (15.811–100%) of 2 SNPs | 100% (15.811–100%) of 2 SNPs |

| P-value of the sign test | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.250 |

P-value threshold for SNP inclusion: refers to p-value of the SNP in the SNP-based linear regression model run in the combined Budapest + Manchester sample. SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, CI confidence interval for the percentage of concordant SNPs, p-value of the sign test: significance of that the percentage of concordant SNPs deviate from that expected by chance

Genes and gene sets in the background of rumination, brooding, and reflection

The top ten hits at the levels of genes and the three different gene sets are shown in Table 3. The complete list of these results and the intercorrelations between the respective methods are shown in Supplementary File 2, Supplementary File 3, and Supplementary File 4 for rumination, brooding, and reflection, respectively. The results for rumination demonstrate that after correction for multiple testing, KCTD12 gene and the set of genes binding miR-383 survived the FDR q < 0.10 threshold. Figure 2a illustrates that KCTD12 SNPs captured in our analysis reside exclusively in the upstream regulatory region of the gene. However, no gene or gene set survived the FDR q < 0.10 threshold for either brooding or reflection.

Table 3.

Top ten hits for rumination, brooding, and reflection in the four categories

| Rumination | Brooding | Reflection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene or gene set | Top ten hits | p-value | q-value | Top ten hits | p-value | q-value | Top ten hits | p-value | q-value |

| Genes | KCTD12 | <0.0001 | 0.0251 | LOC284009 | <0.0001 | 0.1269 | C1QTNF5 | <0.0001 | 0.2308 |

| KLHL33 | <0.0001 | 0.2263 | MFAP5 | <0.0001 | 0.1269 | USP2 | <0.0001 | 0.2308 | |

| TNFSF15 | <0.0001 | 0.2606 | CACNA1D | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | MFRP | <0.0001 | 0.2308 | |

| UMOD | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | C7orf72 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | TOB1 | <0.0001 | 0.2308 | |

| MIR520F | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | VPS33B | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | TOB1-AS1 | <0.0001 | 0.2308 | |

| MIR519E | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | CTDSPL2 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | CADM4 | 0.0001 | 0.2717 | |

| MIR515-1 | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | S100A3 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | RNF26 | 0.0001 | 0.2790 | |

| MIR515-2 | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | EIF3J-AS1 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | DPYSL5 | 0.0001 | 0.2790 | |

| MIR498 | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | LOC101928034 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | ERCC1 | 0.0001 | 0.2884 | |

| MIR520E | 0.0001 | 0.2606 | LOC101926911 | 0.0001 | 0.3592 | CD3EAP | 0.0001 | 0.2884 | |

| C5 | GO_LONG_TERM_MEMORY | 0.0002 | 0.8149 | GO_NOTCH_RECEPTOR_PROCESSING | <0.0001 | 0.2023 | GO_PROXIMAL_DISTAL_PATTERN_FORMATION | 0.0003 | 0.9746 |

| GO_EPHRIN_RECEPTOR_ACTIVITY | 0.0004 | 0.8149 | GO_NOTCH_BINDING | 0.0003 | 0.5573 | GO_RETINOL_METABOLIC_PROCESS | 0.0006 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_REGULATION_OF_DENDRITE_MORPHOGENESIS | 0.0011 | 0.9213 | GO_REGULATION_OF_MEMBRANE_REPOLARIZATION | 0.0014 | 0.9719 | GO_PANCREAS_DEVELOPMENT | 0.0017 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_EPHRIN_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 0.0013 | 0.9213 | GO_CELLULAR_RESPONSE_TO_HEAT | 0.0016 | 0.9719 | GO_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_LEUKOCYTE_MIGRATION | 0.0022 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_TRANSITION_METAL_ION_HOMEOSTASIS | 0.0013 | 0.9213 | GO_VOLTAGE_GATED_CALCIUM_CHANNEL_COMPLEX | 0.0020 | 0.9719 | GO_REGULATION_OF_RESPIRATORY_GASEOUS_EXCHANGE | 0.0026 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_REGULATION_OF_SYNAPTIC_VESICLE_TRANSPORT | 0.0018 | 0.9213 | GO_CALCIUM_CHANNEL_COMPLEX | 0.0027 | 0.9719 | GO_BASAL_LAMINA | 0.0039 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_POSITIVE_CHEMOTAXIS | 0.0019 | 0.9213 | GO_ENDOPLASMIC_RETICULUM_CALCIUM_ION_HOMEOSTASIS | 0.0028 | 0.9719 | GO_CYTOSOLIC_TRANSPORT | 0.0043 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_COLLAGEN_TRIMER | 0.0020 | 0.9213 | GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_KIDNEY_DEVELOPMENT | 0.0029 | 0.9719 | GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_SKELETAL_MUSCLE_TISSUE_DEVELOPMENT | 0.0043 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_GLYCOSAMINOGLYCAN_BINDING | 0.0021 | 0.9213 | GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_INTERLEUKIN_4_PRODUCTION | 0.0037 | 0.9719 | GO_PRIMARY_ALCOHOL_METABOLIC_PROCESS | 0.0045 | 0.9746 | |

| GO_CIRCADIAN_RHYTHM | 0.0022 | 0.9213 | GO_T_TUBULE | 0.0038 | 0.9719 | GO_MICROFILAMENT_MOTOR_ACTIVITY | 0.0047 | 0.9746 | |

| C3 MIR | TCTGATC_MIR383 | 0.0002 | 0.0442 | TCCAGAG_MIR518C | 0.0062 | 0.8342 | GCACCTT_MIR18A_MIR18B | 0.0070 | 0.8978 |

| AACATTC_MIR4093P | 0.0024 | 0.2196 | ACTACCT_MIR196A_MIR196B | 0.0136 | 0.8342 | GAGCCAG_MIR149 | 0.0102 | 0.8978 | |

| ACCATTT_MIR522 | 0.0126 | 0.7223 | AGGGCCA_MIR328 | 0.0184 | 0.8342 | ATTCTTT_MIR186 | 0.0149 | 0.8978 | |

| ATTCTTT_MIR186 | 0.0209 | 0.7223 | TCTGGAC_MIR198 | 0.0279 | 0.8342 | CATTTCA_MIR203 | 0.0236 | 0.8978 | |

| GGCCAGT_MIR193A_MIR193B | 0.0213 | 0.7223 | GAGCCTG_MIR484 | 0.0280 | 0.8342 | TCTGATC_MIR383 | 0.0258 | 0.8978 | |

| CAGTCAC_MIR134 | 0.0238 | 0.7223 | GGGACCA_MIR133A_MIR133B | 0.0338 | 0.8342 | CCAGGGG_MIR331 | 0.0375 | 0.8978 | |

| TCTGGAC_MIR198 | 0.0310 | 0.7223 | CAGTCAC_MIR134 | 0.0359 | 0.8342 | TCCAGAG_MIR518C | 0.0419 | 0.8978 | |

| TCCAGAG_MIR518C | 0.0378 | 0.7223 | CACCAGC_MIR138 | 0.0430 | 0.8342 | CTTTGCA_MIR527 | 0.0504 | 0.8978 | |

| AGTCAGC_MIR345 | 0.0401 | 0.7223 | TACTTGA_MIR26A_MIR26B | 0.0437 | 0.8342 | ATAACCT_MIR154 | 0.0507 | 0.8978 | |

| AAACCAC_MIR140 | 0.0423 | 0.7223 | ATGCTGC_MIR103_MIR107 | 0.0500 | 0.8342 | GGTAACC_MIR4095P | 0.0532 | 0.8978 | |

| C3 TFT | PAX4_03 | 0.0026 | 0.7520 | SF1_Q6 | 0.0014 | 0.6614 | ATCMNTCCGY_UNKNOWN | 0.0008 | 0.4565 |

| MTF1_Q4 | 0.0032 | 0.7520 | MZF1_01 | 0.0024 | 0.6614 | ACAWYAAAG_UNKNOWN | 0.0023 | 0.6212 | |

| OCT1_B | 0.0056 | 0.7520 | CACBINDINGPROTEIN_Q6 | 0.0045 | 0.7805 | FOXO4_01 | 0.0042 | 0.7784 | |

| GGGNRMNNYCAT_UNKNOWN | 0.0080 | 0.7520 | FAC1_01 | 0.0073 | 0.7805 | FXR_IR1_Q6 | 0.0081 | 0.9499 | |

| NF1_Q6_01 | 0.0082 | 0.7520 | TGANNYRGCA_TCF11MAFG_01 | 0.0084 | 0.7805 | TGATTTRY_GFI1_01 | 0.0113 | 0.9499 | |

| TCF11MAFG_01 | 0.0096 | 0.7520 | NFY_C | 0.0087 | 0.7805 | E2F1_Q3 | 0.0117 | 0.9499 | |

| IK3_01 | 0.0106 | 0.7520 | OSF2_Q6 | 0.0133 | 0.7805 | E2F_Q6 | 0.0121 | 0.9499 | |

| IRF7_01 | 0.0109 | 0.7520 | AP4_Q6 | 0.0142 | 0.7805 | E2F_Q4 | 0.0155 | 0.9517 | |

| E2F1_Q4 | 0.0175 | 0.9271 | AP1_Q2_01 | 0.0148 | 0.7805 | NFY_Q6_01 | 0.0162 | 0.9517 | |

| RP58_01 | 0.0199 | 0.9271 | TAAYNRNNTCC_UNKNOWN | 0.0169 | 0.7805 | TTGCWCAAY_CEBPB_02 | 0.0202 | 0.9517 | |

C5: GO gene sets; C3 MIR and C3 TFT: the two motif gene set collections, grouping genes by microRNA target sites or transcriptional factor binding sites, respectively; p-value: empirical p-value based on one million permutations; q-value: false discovery rate correction, done for all analyses within each of the four categories, for each phenotype. Significant hits are marked with bold

Functional effects of the top SNPs on gene expression regulation in the brain

Supplementary Figures 5–11 show FUMA37 results on the genes regulated in brain by the top SNPs according to external chromatin interaction databases38 and the following eQTL databases. GTEx v6 and v7 (refs. 39,40) and BRAINEAC41 comprise several brain regions. However, xQTLServer42 and CommonMind Consortium (CMC)43 samples encompass only the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). FUMA results on the regulated genes in all available tissues and cell types without restriction to brain are displayed in Supplementary Files 2–4 for each phenotype.

Results revealed that top SNPs for rumination on chromosome 3 were associated with expression levels of SRGAP3 and SETD5 in the DLPFC (CMC samples) (Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary File 2). Top rumination SNPs on chromosome 13 influenced expression level of KCTD12 also in the DLPFC (CMC). They also interacted with C13orf45 (LMO7DN) in the hippocampus, DLPFC, and neural progenitor cells (Supplementary Figure 7 and Supplementary File 2).

Most significant SNPs for brooding affected expression level of CDH12 in the DLPFC (CMC) (Supplementary Figure 8 and Supplementary File 3).

Top SNPs for reflection on chromosome 2 had many effects according to external databases (Supplementary Figure 10 and Supplementary File 4). In the DLPFC they altered expression levels of DPYSL5 (CMC and xQTLServer), SLC35F6, FNDC4, MAPRE3 (CMC), and KCNK3 (xQTLServer). In the BA9 region they affected expression levels of GPN1 (GTEx v6) and also KCNK3 (GTEx v7). In the cortex in general, they regulated expression levels of DPYSL5 (GTEx v6 and v7) and KCNK3 (GTEx v7). Furthermore, they altered DPYSL5 expression in hippocampus, substantia nigra (GTEx v7), cerebellum, cerebellar hemisphere (GTEx v6 and v7), and white matter (BRAINEAC).

Reflection top SNPs on chromosome 12 influenced expression level of ATXN7L3B in the inferior olivary nucleus (BRAINEAC), and also took part in chromatin interactions with TPH2 and TRHDE in neural progenitor cells (Supplementary Figure 11 and Supplementary File 4).

Discussion

We present a GWAS of ruminative response style and its two subtypes. The association of KCTD12 gene and miR-383-binding genes with rumination appears to be robust because these results survived correction for multiple testing. We discuss the implications for the biological foundations of rumination below. While previously reported candidate gene results were not replicated at the more stringent genome-wide level, new candidate genes emerged in our study.

In spite of their diversity, we only discuss three aspects of our findings: (i) transdiagnostic nature of rumination, (ii) relevant brain regions in rumination, and (iii) poligenicity of rumination.

Transdiagnostic nature of rumination, brooding, and reflection, supported by KCTD12, miR-383, and suggestively significant SNPs

KCTD12, significant at gene level in the present study, emerged as a candidate in a bipolar depression GWAS among Han Chinese44. Rumination has indeed been suggested to show higher levels in bipolar than in major depressive patients45, and to be independent of bipolar patients’ mood state46.

Suggestively significant SNPs for brooding regulated brain expression level of CDH12, which result corroborates the genetic relationship of rumination phenotypes with bipolar depression and extends it to other disorders. CDH12 has been previously associated with bipolar depression, major depression, and schizophrenia47,48, and also with bipolar-type schizoaffective disorder49, suicidal behavior50,51, and metamphetamine and alcohol dependence48. CHRM3 gene, highlighted by a suggestive SNP for reflection, has also been implicated in schizophrenia52 but binding results of its encoded protein, muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3, are conflicting with regard to bipolar and major depressive patients53,54. A robust evidence underpins the role of rumination in major depression55, and there is evidence on its relevance also in psychosis56, alcohol abuse5, and substance abuse6.

Underscoring the genetics-based importance of rumination phenotypes in suicidality, the tryptophan hydroxylase TPH2 gene, implicated in chromatin interactions of SNPs suggestive for reflection, is related to hopelessness, a suicidality risk phenotype57. It has to be noted, however, that rumination and brooding have shown a more consistent positive association with suicide phenotypes than reflection58.

The set of genes binding miR-383, significant for rumination after correction for multiple testing, can also be settled in this transdiagnostic context, specifically that of stress and binge eating which can be interpreted as a cause and a possible consequence of rumination, respectively1,2,6. MiR-383 expression has been revealed to be upregulated in the rat serum after chronic unpredictable mild stress59, and in the hypothalamus of mice deficient of either leptin or leptin receptor, with an intraperitoneal injection of leptin downregulating its expression60. Serum leptin levels have shown conflicting associations with binge eating symptoms61,62. Nevertheless, direction of effects with regard to miR-383 and rumination needs to be investigated by future studies.

The 12q21.1 region, comprising suggestively significant SNPs for reflection, has been associated with mental retardation63. Top SNPs for rumination also underpin the genetic link with mental retardation, since they affected brain expression levels of SRGAP3 and SETD5, implicated in this disorder64,65, but see ref. 66. However, rumination has shown a positive correlation only with verbal but not with non-verbal intelligence scores67.

While these disorders represent diverse phenotypes, based on these overlapping genetic results we propose rumination as an overarching trait, sharing biological underpinnings with several psychiatric disorders.

Relevant brain regions in rumination, brooding, and reflection, based on gene regulation databases and previous literature

Although the present results do not provide direct evidence that the implicated genes exert their effect on rumination and its subtypes via their expression in certain brain regions, we discuss three regions most salient from our results: DLPFC, hippocampus, and cerebellum. The role of the DLPFC68 and hippocampus69,70 has been suggested in rumination, but results on the role of the cerebellum have yielded contradictory associations71,72. Nevertheless, several other brain regions or even other tissues may play a role in mediating between these genes and rumination but they are not discussed here.

While we demonstrated that the expression of our significant gene, KCTD12, was regulated by our top SNPs only in DLPFC, its relevance has been suggested in the hippocampus and the cerebellum by previous literature. For example, Kctd12-KO mice showed an increased intrinsic excitability of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus in addition to an increased fear-learning phenotype73. KCTD12 encodes an auxiliary subunit exclusively associated with the GABAB receptor74. The encoded protein enhances receptor signaling at the cell surface75 and rapidly desensitizes the K+ current response mediated by Kir3 channels after GABAB activation74,76. The Kir3.2 (GIRK2) subunit of Kir3 channels is encoded by the KCNJ6 gene associated with rumination in our previous results19. GABAB and GIRK2 are co-localized77 and have a concerted action in the hippocampus78–80 and in cerebellar Purkinje cells81. Antagonism of the GABAB receptor has been suggested to have antidepressant properties82,83, and rapid antidepressants may act through decoupling GABAB from the Kir3 channel via the adaptor protein 14-3-3eta80, highlighting the importance of Kir3 activation among the numerous downstream effects of GABAB in current depression level. On the other hand, the possible action of KCTD12 on rumination can also be viewed from a developmental perspective, since it showed extremely low expression in the adult cerebrum and cerebellum but high brain expression levels in the fetal stages in a study84. This may resolve contradictions concerning brain regions between our present results and previous literature to some extent.

Nevertheless, top SNPs of both KCNK3, suggested in astrocytes of temporal lobe epilepsy patients’ hippocampus85, and MAPRE3, implicated in dendritic spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in mature hippocampal neurons86, have affected their expression levels only in the DLPFC or cortex in our results but not in the hippocampus.

With regard to the cerebellum, RBM17 emphasizes Purkinje neurons87. The 12q21.1 region has been linked to cerebellar ataxia88, and specifically the ATXN7L3B (lnc-SCA7) gene within has been proposed to have a role in spinocerebellar ataxia89. However, our top SNPs influenced ATXN7L3B expression within the inferior olivary nucleus.

In contrast to the controversies detailed above, DPYSL5 (or CRMP5), a gene implicated in reflection in our results, yielded consistent associations between expression databases and previous literature, stressing the importance of the hippocampus and the cerebellum. It is involved in brain development and in adult neurogenesis90, in addition to the dendrite morphology and synaptic plasticity of cerebellar Purkinje cells91. In mouse embryonic hippocampal neurons DPYSL5 inhibits neurite outgrowth92, dendrite outgrowth and formation93, and decreases mitochondrial content in dendrites94, again pointing to a possible critical window of rumination establishment during fetal development of the hippocampus.

To summarize, there are both consistencies and inconsistencies between gene regulation databases and previous literature regarding these three most salient brain regions in our results.

Polygenicity of rumination, brooding, and reflection

No SNP association survived correction for multiple testing but there were several suggestively significant results.

Lack of significance both in SNP-based association tests and SNP heritability may be the consequence of the statistical power of our study, because of the weak effects, and limited sample size in relation to a large number of SNPs95. However, the lack of power is offset by our replication subsamples from Budapest and Manchester. The sign test analysis demonstrated the replicability of the effects of independent lead SNPs: the rate of concordant SNPs significantly deviated from that expected by chance both for the SNPs with p-values less than 0.05 and 1 × 10–3. However, this deviation was not significant for the most significant (p < 1 × 10–5) very few SNPs. This genetic concordance is also remarkable because the two subsamples differed from each other not only in rumination levels but also in frequencies of most disorders related to rumination.

Limitations

Although testing at multiple levels and utilizing external databases of gene expression and chromatin interaction convey strengths to our study, one of its weaknesses is the low sample size29. This not only limits the power of our tests, but also explains that we chose mega-analysis instead of meta-analysis, despite differences in the rumination phenotypes between the two subsamples.

Another limitation is that we measured rumination with only one method, thus we were not able to create any latent rumination variable, like Johnson et al.11 did with RRS brooding, RRS reflection, and the rumination component of the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire. Genome-wide investigation of other rumination measurements, as well as GWASes within specific subpopulations, such as depressed patients, would also be inevitable.

Conclusions

Although our present study is limited by its low sample size, the replicability of the effects of independent lead SNPs between the two subsamples is remarkable given the phenotypic differences between them. This underlines the robustness of the genetic background of rumination across European populations.

The genetically underpinned overarching nature of the rumination endophenotype implies its clinical relevance in several fields.

Further studies are needed to shed light on the mediating pathways between the implicated genes and rumination. Developmental and adult perspectives can be highlighted in the association of rumination with specific brain regions, such as DLPFC, hippocampus, and cerebellum. A possible cooperation of KCTD12, GIRK2, and GABAB receptor proteins should also be clarified in the future.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Sixth Framework Program of the European Union (NewMood, LSHM-CT-2004-503474); by the Hungarian Brain Research Program (Grants KTIA_13_NAPA-II/14 and 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002), and the National Development Agency (Grant KTIA_NAP_13-1-2013-0001); by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungarian National Development Agency, Semmelweis University and the Hungarian Brain Research Program (Grant KTIA_NAP_13-2-2015-0001, MTA-SE-NAP B Genetic Brain Imaging Migraine Research Group; and Grant NAP-B KTIA_NAP_13-2014-0011, MTA-SE NAP-B Molecular Psychiatry Research Group); by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA-SE Neuropsychopharmacology and Neurochemistry Research Group); by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre; by OTKA 119866; by TAMOP-4.2.1.B-09/1/KMR-2010-0001; by the New National Excellence Program of The Ministry of Human Capacities (ÚNKP-16-3; ÚNKP-17-3-III-SE-2; ÚNKP-17-4-I-SE-8; and ÚNKP-18-4-SE-33); and by The Ministry of Human Capacities in the frame of Institutional Excellence Program for Higher Education. X.G. is recipient of the Janos Bolyai Research Fellowship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. None of the sponsors had any role in designing the study, collecting and analyzing data, or in preparing the paper. We thank Diana Chase, Darragh Downey, Kathryn Lloyd-Williams, Emma J. Thomas, and Zoltan G. Toth for their assistance in the recruitment and data acquisition processes; and Charles Curtis for his assistance in genotyping (King’s College London, SGDP Centre, Institute of Psychiatry). We also thank the Heaton Mersey and the Cheadle Medical Practices for their assistance in recruitment.

Conflict of interest

J.F.W.D. has share options in P1vital, and he has performed research, consultancy, and speaking engagements (all fees are paid to the University of Manchester to reimburse them for the time taken) for AstraZeneca, Autifony, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, P1vital, Schering Plough, and Servier. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-019-0454-1).

References

- 1.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins ER. A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011;6:589–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006;60:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen BA, Christenfeld NJ. Cardiovascular disease and psychiatric comorbidity: the potential role of perseverative cognition. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:791017. doi: 10.1155/2009/791017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA. Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: tests of gender differences. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2002;16:391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokonyei G, et al. Rumination in migraine: mediating effects of brooding and reflection between migraine and psychological distress. Psychol. Health. 2016;31:1481–1497. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1235166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Li XY. Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent rumination and its association with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013;41:1289–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore MN, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on rumination, distraction, and depressed mood in adolescence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2013;1:316–322. doi: 10.1177/2167702612472884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson DP, et al. A twin study examining rumination as a transdiagnostic correlate of psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016;4:971–987. doi: 10.1177/2167702616638825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antypa N, Van der Does AJ. Serotonin transporter gene, childhood emotional abuse and cognitive vulnerability to depression. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:615–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canli T, et al. Neural correlates of epigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16033–16038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601674103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clasen PC, Wells TT, Knopik VS, McGeary JE, Beevers CG. 5-HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms moderate effects of stress on rumination. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:740–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eszlari N, et al. Brooding subtype of rumination is modulated by the interplay between serotonin receptor 2A gene and childhood adversity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(S1):S77–S78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borelli JL, et al. Interactive effects of attachment and FKBP5 genotype on school-aged children's emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Behav. Brain. Res. 2017;325(Pt B):278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halldorsdottir T, et al. FKBP5 moderation of the relationship between childhood trauma and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;84:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eszlari N, et al. Distinct effects of folate pathway genes MTHFR and MTHFD1L on ruminative response style: a potential risk mechanism for depression. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;1:19. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazary J, et al. Epistatic interaction of CREB1 and KCNJ6 on rumination and negative emotionality. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilt LM, Sander LC, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Simen AA. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predicts rumination and depression differently in young adolescent girls and their mothers. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;429:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juhasz G, et al. The CREB1-BDNF-NTRK2 pathway in depression: multiple gene-cognition-environment interactions. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:762–771. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone LB, McGeary JE, Palmer RH, Gibb BE. Identifying genetic predictors of depression risk: 5-HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms are associated with rumination and co-rumination in adolescents. Front. Genet. 2013;4:246. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beevers CG, Wells TT, McGeary JE. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism is associated with rumination in healthy adults. Emotion. 2009;9:579–584. doi: 10.1037/a0016189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman B, et al. DNA from buccal swabs recruited by mail: evaluation of storage effects on long-term stability and suitability for multiplex polymerase chain reaction genotyping. Behav. Genet. 2003;33:67–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1021055617738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman JR, et al. Quality control, imputation and analysis of genome-wide genotyping data from the Illumina HumanCoreExome microarray. Brief Funct. Genomics. 2016;15:298–304. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (Sage Publications, 2005).

- 27.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyde CL, et al. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1031–1036. doi: 10.1038/ng.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ripke S, et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013;18:497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schork AJ, et al. All SNPs are not created equal: genome-wide association studies reveal a consistent pattern of enrichment among functionally annotated SNPs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makambi K. Weighted inverse chi-square method for correlated significance tests. J. Appl. Stat. 2003;30:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kost JT, McDermott MP. Combining dependent P-values. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2002;60:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delongchamp R, Lee T, Velasco C. A method for computing the overall statistical significance of a treatment effect among a group of genes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-S2-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li MX, Gui HS, Kwan JS, Sham PC. GATES: a rapid and powerful gene-based association test using extended Simes procedure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li MX, Sham PC, Cherny SS, Song YQ. A knowledge-based weighting framework to boost the power of genome-wide association studies. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Network and Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Psychiatric genome-wide association study analyses implicate neuronal, immune and histone pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:199–209. doi: 10.1038/nn.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:017–01261. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitt AD, et al. A compendium of chromatin contact maps reveals spatially active regions in the human genome. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2042–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Battle A, Brown CD, Engelhardt BE, Montgomery SB. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramasamy A, et al. Genetic variability in the regulation of gene expression in ten regions of the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/nn.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng B, et al. An xQTL map integrates the genetic architecture of the human brain's transcriptome and epigenome. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1418–1426. doi: 10.1038/nn.4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fromer M, et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1442–1453. doi: 10.1038/nn.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee MT, et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar I disorder in the Han Chinese population. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:548–556. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim S, Yu BH, Lee DS, Kim JH. Ruminative response in clinical patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. J. Affect Disord. 2012;136:e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silveira EdM, Jr, Anna MKS., Jr Rumination in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2015;37:256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, Long F, Cai B, Chen G. A novel relationship for schizophrenia, bipolar and major depressive disorder. Part 5: A hint from chromosome 5 high density association screen. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017;9:2473–2491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redies C, Hertel N, Hubner CA. Cadherins and neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain Res. 2012;27:130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamshere ML, et al. Genetic utility of broadly defined bipolar schizoaffective disorder as a diagnostic concept. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2009;195:23–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sokolowski M, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. Polygenic associations of neurodevelopmental genes in suicide attempt. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1381–1390. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thalmeier A, et al. Gene expression profiling of post-mortem orbitofrontal cortex in violent suicide victims. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:217–228. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Q, et al. The CHRM3 gene is implicated in abnormal thalamo-orbital frontal cortex functional connectivity in first-episode treatment-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2016;46:1523–1534. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibbons AS, Scarr E, McLean C, Sundram S, Dean B. Decreased muscarinic receptor binding in the frontal cortex of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder subjects. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;116:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeon WJ, Gibbons AS, Dean B. The use of a modified [3H]4-DAMP radioligand binding assay with increased selectivity for muscarinic M3 receptor shows that cortical CHRM3 levels are not altered in mood disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;47:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cernis E, et al. The perseverative thinking questionnaire in patients with persecutory delusions. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2016;44:472–481. doi: 10.1017/S1352465815000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lazary J, et al. Hopelessness, a potential endophenotpye for suicidal behavior, is influenced by TPH2 gene variants. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;36:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers ML, Joiner TE. Rumination, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts: a meta-analytic review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2017;21:132–142. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duan DM, Dong X, Tu Y, Liu P. A microarray study of chronic unpredictable mild stress rat blood serum with electro-acupuncture intervention. Neurosci. Lett. 2016;627:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Derghal A, et al. Leptin is required for hypothalamic regulation of miRNAs targeting POMC 3'UTR. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:172. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eddy KT, et al. Appetite regulatory hormones in women with anorexia nervosa: binge-eating/purging versus restricting type. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2015;76:19–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller R, et al. Serum leptin and loss of control eating in children and adolescents. Int. J. Obes. 2014;38:397–403. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Curry CJ, et al. Homozygous deletions of a copy number change detected by array CGH: a new cause for mental retardation? Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2008;1:1903–1910. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grozeva D, et al. De novo loss-of-function mutations in SETD5, encoding a methyltransferase in a 3p25 microdeletion syndrome critical region, cause intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shuib S, et al. Microarray based analysis of 3p25-p26 deletions (3p- syndrome) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2009;10:32824. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamdan FF, et al. No association between SRGAP3/MEGAP haploinsufficiency and mental retardation. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:675–676. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Penney AM, Miedema VC, Mazmanian D. Intelligence and emotional disorders: is the worrying and ruminating mind a more intelligent mind? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2015;74:90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Raedt R, Koster EH. Understanding vulnerability for depression from a cognitive neuroscience perspective: a reappraisal of attentional factors and a new conceptual framework. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2010;10:50–70. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zamoscik V, Huffziger S, Ebner-Priemer U, Kuehner C, Kirsch P. Increased involvement of the parahippocampal gyri in a sad mood predicts future depressive symptoms. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014;9:2034–2040. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mandell D, Siegle GJ, Shutt L, Feldmiller J, Thase ME. Neural substrates of trait ruminations in depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2014;123:35–48. doi: 10.1037/a0035834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Machino A, et al. Possible involvement of rumination in gray matter abnormalities in persistent symptoms of major depression: an exploratory magnetic resonance imaging voxel-based morphometry study. J. Affect Disord. 2014;168:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Najib A, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Bohning DE, George MS. Regional brain activity in women grieving a romantic relationship breakup. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:2245–2256. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cathomas F, et al. Altered emotionality and neuronal excitability in mice lacking KCTD12, an auxiliary subunit of GABAB receptors associated with mood disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 2015;17:8. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Turecek R, et al. Auxiliary GABAB receptor subunits uncouple G protein betagamma subunits from effector channels to induce desensitization. Neuron. 2014;82:1032–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ivankova K, et al. Up-regulation of GABA(B) receptor signaling by constitutive assembly with the K+ channel tetramerization domain-containing protein 12 (KCTD12) J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:24848–24856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.476770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adelfinger L, et al. GABAB receptor phosphorylation regulates KCTD12-induced K(+) current desensitization. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;91:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.David M, et al. Interactions between GABA-B1 receptors and Kir 3 inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2172–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kulik A, et al. Compartment-dependent colocalization of Kir3.2-containing K+ channels and GABAB receptors in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4289–4297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Workman ER, et al. Rapid antidepressants stimulate the decoupling of GABA(B) receptors from GIRK/Kir3 channels through increased protein stability of 14-3-3eta. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:298–310. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fernandez-Alacid L, et al. Subcellular compartment-specific molecular diversity of pre- and post-synaptic GABA-activated GIRK channels in Purkinje cells. J. Neurochem. 2009;110:1363–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cryan JF, Slattery DA. GABAB receptors and depression. Current status. Adv. Pharmacol. 2010;58:427–451. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(10)58016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jacobson LH, Vlachou S, Slattery DA, Li X, Cryan JF. The gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptor in depression and reward. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;83:963–976. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Resendes BL, et al. Isolation from cochlea of a novel human intronless gene with predominant fetal expression. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2004;5:185–202. doi: 10.1007/s10162-003-4042-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim JE, et al. Changes in TWIK-related acid sensitive K+-1 and -3 channel expressions from neurons to glia in the hippocampus of temporal lobe epilepsy patients and experimental animal model. Neurochem. Res. 2011;36:2155–2168. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jaworski J, et al. Dynamic microtubules regulate dendritic spine morphology and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tan Q, et al. Extensive cryptic splicing upon loss of RBM17 and TDP43 in neurodegeneration models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:5083–5093. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajakulendran S, Roberts J, Koltzenburg M, Hanna MG, Stewart H. Deletion of chromosome 12q21 affecting KCNC2 and ATXN7L3B in a family with neurodevelopmental delay and ataxia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2013;84:1255–1257. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tan JY, et al. Cross-talking noncoding RNAs contribute to cell-specific neurodegeneration in SCA7. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:955–961. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Veyrac A, et al. CRMP5 regulates generation and survival of newborn neurons in olfactory and hippocampal neurogenic areas of the adult mouse brain. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamashita N, et al. CRMP5 (collapsin response mediator protein 5) regulates dendritic development and synaptic plasticity in the cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:1773–1779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5337-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brot S, et al. Collapsin response-mediator protein 5 (CRMP5) phosphorylation at threonine 516 regulates neurite outgrowth inhibition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014;40:3010–3020. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brot S, et al. CRMP5 interacts with tubulin to inhibit neurite outgrowth, thereby modulating the function of CRMP2. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:10639–10654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0059-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brot S, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein 5 (CRMP5) induces mitophagy, thereby regulating mitochondrion numbers in dendrites. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:2261–2276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.490862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petschner P, Bagdy G, Tothfalusi L. [The problem of small "n" and big "P" in neuropsycho-pharmacology, or how to keep the rate of false discoveries under control] Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 2015;17:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.