Abstract

The purpose of this study was to optimize primary and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for detecting the microsporidia Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in fecal samples from dairy calves. PCR for these microsporidia were compared to immunofluorescence assays (IFA) based on commercially available monoclonal antibodies specific for outer wall proteins of Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi. Fecal samples were collected from 15 dairy calves and processed by molecular sieving followed by salt floatation to recover Enc. intestinalis and Ent. bieneusi spores. An aliquot of the final supernatant was applied to glass slides for IFA testing; another aliquot was extracted for total DNA using a QIAamp Stool Mini-Kit for primary and nested Enc. intestinalis- and Ent. bieneusi-specific PCR analysis. Internal standards were generated for both Enc. intestinalis and Ent. bieneusi PCR assays to control for false negative reactions due to the presence of inhibitors commonly found in fecal samples. Using the commercial MicrosporIFA (Waterborne, Inc.) as the gold standard, the optimized Enc. intestinalis PCR method provided 85.7% sensitivity and 100% specificity with a kappa value = 0.865. Likewise, using the commercial BienusiGlo IFA (Waterborne, Inc.) as the gold standard, the optimized Ent. bieneusi PCR method provided 83.3% sensitivity and 100% specificity with a kappa value = 0.857. Sequencing of amplicons from both PCR assays confirmed the presence of Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi. In conclusion, our optimized assays for recovering and detecting Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi in feces from dairy calves provides a valuable alternative to traditional IFA methods that require expertise to identify extremely small microsporidia spores (~ 2.0 µm). Our assays also improve upon existing molecular detection techniques for these microsporidia by incorporating an internal standard to control for false negative reactions.

Keywords: Encephalitozoon intestinalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Immunofluorescence assay, PCR, Internal standard

Introduction

The microsporidia Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi are known agents of diarrheal disease in humans and dairy cattle (Stentiford et al. 2016; Han and Weiss 2017). Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis are considered the most common cause of microsporidia-associated disease in humans (Didier 2005; Saigal et al. 2013). Preventing human microsporidiosis requires managing sources of the parasite, such as infected dairy calves. Accurate diagnosis is important because treatment decisions depend on which microsporidium is the causative agent. For instance, albendazole is effective against Enc. intestinalis, while fumagillin is recommended for treatment of Ent. bieneusi infection (Han and Weiss 2017). In the past, microsporidia isolated from environmental water or in stool samples have been detected using vital stains such as Modified Trichrome (MT) or Uvitex 20. However, these staining methods are not microsporidia-specific and require considerable expertise to reliably identify spores (Enriquez et al. 1997). Immunofluorescence assays (IFA) utilizing polyclonal sera that cross-reacts between Ent. bieneusi and Enc. intestinalis or with monoclonal antibodies that are genus-specific has improved the reliability of detection in various matrices, including human and animal fecal slurries (Beckers et al. 1996; Enriquez et al. 1997; Alfa Cisse et al. 2002; Li et al. 2003; Barbosa et al. 2009). However, the extremely small size of microsporidia spores [~ 2.0 µm in the longest dimension (Moura et al. 1999)] and the difficulty in confidently identifying spores in complex matrices that regularly contain auto-fluorescencing material has prompted the development of molecular techniques to detect these microorganisms. A number of PCR-based techniques that either involve gel electrophoresis to identify amplicons of the expected size or utilize real-time PCR have been applied for detecting microsporidia in both human stool and environmental water (Müller et al. 1999; Dowd et al. 2003; Izquierdo et al. 2011). These PCR methods have performed favorably in comparison to IFA and appear to be superior to staining with MT or Uvitex 20 (Müller et al. 1999; Katzwinkel-Wladarsch et al. 1997; Ghoshal et al. 2016). In our experience and as reported by others, PCR is extremely useful for detecting low numbers of microsporidia in various matrices, but the presence of inhibitors of PCR often present in stool samples and concentrated water compromises the reliability of PCR due to false negative reactions (Wolk et al. 2002; Hoffman et al. 2007; Hawash et al. 2015). The purpose of the present study was to develop a rapid method to isolate microsporidium spores from calf feces and to optimize existing PCR methods for Enc. intestinalis and Ent. bieneusi by developing an internal standard for each assay that provides appropriate controls against false negative PCR. The target of the PCR assays are ribosomal DNA sequences which are known to exist in multiple copies thereby increasing the sensitivity of the detection method. The sensitivity of Enc. intestinalis detection was increased further by incorporating a nested PCR in the assay.

Materials and methods

Sources of microsporidium spores and sample preparation

As a positive control, Encephalitozoon intestinalis (ATCC #50507), was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and grown in MDBK cells using standard procedures (Lallo et al. 2015). For estimating assay specificity and sensitivity, fecal samples (n = 15) from 1 to 4 month old dairy calves housed at the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center were collected into sterile polypropylene cups and transported to the laboratory for isolating microsporidia spores using a series of molecular sieves. In brief, 2 g of a calf fecal sample was transferred to a 50 ml polypropylene test tube containing 35 ml deionized H2O. The fecal slurry was disrupted by vortexing for 15 s and then passed through a succession of 3 different molecular sieves—a 500 µm (sieve no. 35) followed by a 250 µm (sieve no. 60), and finally a 90 µm (sieve no. 170) (Newark Wire Cloth Co., Newark, NJ) with final flow-thru collected in a 250 ml beaker. The sieves were rinsed with 15 ml deionized H2O, and the entire flow-thru transferred to a 50 ml polypropylene test tube, and a final volume of 50 ml achieved by the addition of deionized H2O. The tubes were centrifuged at 1350 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the spores in the pellet were suspended in 15 ml saturated NaCl, transferred to a 15 ml polypropylene test tube followed by centrifugation at 1350 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The upper 5 ml supernatant containing microsporidia spores was transferred to a 50 ml polypropylene test tube containing 45 ml deionized H2O, and the tubes were centrifuged at 1350 g for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by resuspension of the spores in the pellet with 1.0 ml deionized H2O.

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

Microsporidia isolated from fecal slurries using the procedure described above were applied (10 µl/well) to individual wells of 8-well slides and allowed to air-dry. The identification of Enc. intestinalis was accomplished using the Microspor-FA kit and procedures provided by the manufacturer (Waterborne, Inc., New Orleans, LA). The identification of Ent. bieneusi was accomplished using the Bienusi-Glo kit and procedures provided by the manufacturer (Waterborne, Inc.). After IFA staining, the slides were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, allowed to air-dry, and then each well received 5 µl Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and the entire slide overlaid with a glass coverslip. The slides were examined by epifluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss microscope at 400× magnification. Images were captured using a Zeiss AxioScope camera and AxioVision imaging software.

Molecular identification of Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi

An aliquot (0.5 ml) of the microsporidium spores recovered from calf feces were extracted for DNA using a QIAamp Stool Mini-Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA from spin column eluates were EtOH-precipitated, washed with 70% EtOH, air-dried, and suspended in 50 µl 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA. The DNA concentration was estimated by O.D. 260/280 reading on a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE). An existing PCR assay for detecting Enc. intestinalis based on the internal transcribed spacer 1 ribosomal DNA (ITS1 rDNA) (David et al. 1996) was optimized by producing and incorporating an internal standard to control for false negative reactions due to the presence of PCR inhibitors following described methodologies (Ross et al. 1995). Also, this assay was extended to include primers for nested PCR to improve detection sensitivity (Table 1). A similar approach was taken for Ent. bieneusi following the described 16S rDNA-based PCR technique using primary and nested PCR primers (Table 1) (Buckholt et al. 2002). Amplification of Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi rDNA in a primary PCR was conducted using approx. 10 ηg total DNA in 1X PCR reaction buffer containing 0.625 U Taq polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), 20 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µg/µl BSA, and 20 µM of the appropriate forward and reverse primer in a final volume of 25 µl (Table 1). Each primary PCR also contained the appropriate internal standard (see below) to control for false negative reactions. Nested PCR was conducted using 1 µl of the primary PCR using the same reagent concentrations, and the appropriate nested PCR primers (Table 1). PCR was conducted on a T100 Thermal Cycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and consisted of preliminary denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min., followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55–63 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min (Table 1). Amplification products were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Sambrook et al. 1989), followed by EtBr staining of the gels, and capture on a CCD camera (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for primary and nested PCR amplification of Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi and for generation of internal standard for inclusion in primary amplification to control for false negative PCR

| Primer name | Microsporidian | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Purpose | Amplicon size (bp) | Ta (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eint-F | Enc. intestinalis | GGGGGCTAGGAGTGTTTTTG | Primary | 950 | 63 | David et al. (1996) |

| Eint-R | Enc. intestinalis | CAGCAGGCTCCCTCGCCATC | Primary | David et al. (1996 | ||

| Eint-F Comp | Enc. intestinalis | GGGGGCTAGGAGTGTTTTTGATGGCCCGACAAGC | Competitor | 600 | 63 | This study |

| Eint-R Comp | Enc. intestinalis | CAGCAGGCTCCCTCGCCATCCTATTCGGTGTCTA | Competitor | This study | ||

| Eint-F1 | Enc. intestinalis | AGAGGTTTGGCAGAGGACGA | Nested | 450 | 58 | This study |

| Eint-R1 | Enc. intestinalis | AAGGGTCTCACATCTTACGCA | Nested | This study | ||

| Eb-ITS3 | Ent. bieneusi | GGTCATAGGGATGAAGAG | Primary | 435 | 57 | Buckholt et al. (2002) |

| Eb-ITS4 | Ent. bieneusi | TTCGAGTTCTTTCGCGCTC | Primary | Buckholt et al. (2002) | ||

| Eb-ITS3 Comp | Ent. bieneusi | GGTCATAGGGATGAAGAGATGGCCCGACAAGC | Competitor | 600 | 57 | This study |

| Eb-ITS4 Comp | Ent. bieneusi | TTCGAGTTCTTTCGCGCTCCTATTCGGTGTCTA | Competitor | This study | ||

| EB-ITS1 | Ent. bieneusi | GCTCTGAATATCTATGGCT | Nested | 390 | 55 | Buckholt et al. (2002) |

| EB-ITS2 | Ent. bieneusi | ATCGCCGACGGATCCAAGTG | Nested | Buckholt et al. (2002) |

Underlined sequences are identical to respective forward and reverse primers used in primary PCR

Preparation of internal standard

The internal standards for Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi PCR were prepared using standard procedures (Ross et al. 1995). In brief, hybrid primers containing an upstream sequence identical to either EintF, EintR, EB3, or EB4 were synthesized to contain a downstream sequence identical to an irrelevant DNA entity (NcGRA7, GenBank Accession No. U82229) (Table 1). The size of the internal standard (~ 600 bp) was designed to be discernable from the primary PCR target sequence. The internal standard amplification products were size-fractionated on polyacrylamide gels, excised from the gel after EtBr staining and eluted overnight at 37 °C in elution buffer containing 0.1% SDS (Sambrook et al. 1989). The next day, eluates were removed to a clean 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube, EtOH-precipitated, washed with 70% EtOH, air-dried, and suspended in 3 µl DNase-free H2O, followed by overnight ligation at 4 °C to the TA cloning vector pGemT-Easy (Clontech) using instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The ligation mixtures were used to transform Escherichia coli DH5 using standard procedures (Hanahan 1983) followed by plating on LB-XIA agar plates containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin, 0.1 mM isopropyl thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and 20 µg/ml 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl -D-Galactopyranoside (XGAL). White colonies appearing on the XIA plates were amplified by “colony PCR” using M13 universal and reverse primers and PCR conditions identical to those above, followed by acrylamide gel electrophoresis to confirm expected size of inserts. Recombinant pGEMT-Easy plasmid harboring the Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi internal standard were prepared from overnight cultures using a Mini DNA Kit (Qiagen). PCR was conducted on serial dilutions of the recombinant plasmids harboring the internal standards using the appropriate forward and reverse primer combination (i.e. EintF/R or EB3/4) to identify an optimum amount of internal standard to include in the respective PCR.

Identity confirmation of Encephalitozoon intestinalis or Enterocytozoon bieneusi amplification products

Primary and nested PCR amplification products were excised from polyacrylamide gels, eluted overnight, inserted into pGemT Easy and used to transform DH5 E. coli as outline above. White colonies appearing on the XIA plates were amplified by “colony PCR” using M13 universal and reverse primers and PCR conditions identical to those above, followed by acrylamide gel electrophoresis to confirm expected size of inserts. Recombinant pGEMT-Easy plasmid was prepared from overnight cultures (n = 3/insert) using a Mini DNA Kit (Qiagen) and subjected to DNA sequencing using M13 universal or reverse primers and conducted by a commercial company (Eurofins Genomics, Louisville, KY). The DNA sequences were used to BLAST-N the GenBank database to confirm Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi identity.

Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value of both Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi PCRs were calculated using standard techniques (Watson and Petrie 2010). Kappa values were calculated for both PCR assays using described procedures (Watson and Petrie 2010).

Results and discussion

Immunofluorescence assay

Application of the Microspor-FA to fecal smears from 15 dairy calves detected a wide range in the number of Enc. intestinalis and Ent. bieneusi spores (Fig. 1). In general, feces containing high numbers of Enc. intestinalis spores were easily read as positive (Fig. 1a), whereas those fecal samples with few spores presented some difficulty in discerning positivity (Fig. 1c). IFA using Bienusi-Glo revealed a similar finding—fecals with numbers of Ent. bieneusi spores were easy to score as positive (Fig. 1b), whereas it was difficult to score those with low numbers of spores with any certainty (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of fecal smears from dairy calves containing high (a), low (c), or negligible (e) numbers of Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores with commercial MicrosporFA monoclonal antibodies or fecal smears from dairy calves containing containing high (b), low (d), or negligible (f) numbers of Enterocytozoon bieneusi spores with commercial BienusiGlo monoclonal antibodies. Arrows point to representative reactive spore

Encephalitozoon intestinalis or Enterocytozoon bieneusi PCR

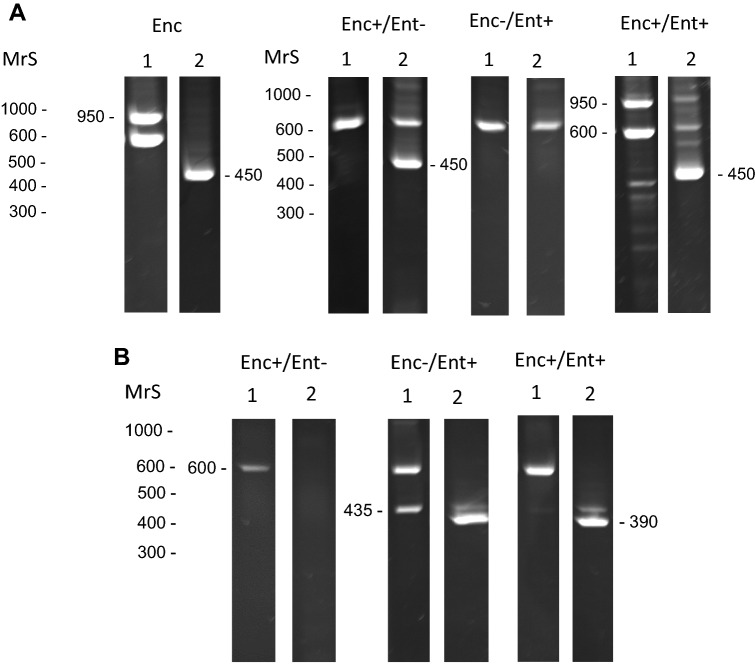

Primary Enc. intestinalis PCR from cell-culture-derived Enc. intestinalis generated the target (950 bp) and internal standard (600 bp) amplicons at the expected size (Fig. 2a). Likewise, nested Enc. intestinalis PCR of primary PCR generated the target amplicons (450 bp) product at the expected size (Fig. 2a). This is probably not surprising given that DNA in the samples were derived solely from Enc. intestinalis spores. Testing of Ent. bieneusi primary and nested PCR could not be performed on pure Ent. bieneusi spores because this microsporidian cannot be grown in vitro, but was useful in detecting Ent. bieneusi in calf feces (see below).

Fig. 2.

a Primary and nested Encephalitozoon intestinalis-specific PCR assay of cell culture-derived Enc. intestinalis (Enc) or spore DNA obtained from Enc. intestinalis positive or negative and Ent. bieneusi positive or negative calves; b Primary and nested Ent. bieneusi-specific PCR analysis of Enc. intestinalis positive or negative and Ent. bieneusi positive or negative calves. MrS, molecular mass markers. Observed size of amplication products: 600-internal standards, 950-Enc. intestinalis amplicon from primary PCR, 450-Enc. intestinalis amplicon from nested PCR, 435-Ent. bieneusi amplicon from primary PCR, 390-Ent. bieneusi amplicon from nested PCR

Primary and nested Enc. intestinalis PCR proved useful for discriminating between Microspor-FA positive and Microspor-FA negative fecal samples. Aside from one sample (calf no. 7), all fecals that were Enc. intestinalis-IFA positive gave rise to amplicons of expected size in nested PCR (450 bp) (Table 2). Nested PCR was required to generate a detectable product in all, but one of the samples (calf no. 1). In this sample, amplification of the 950 bp target was observed after primary PCR (Fig. 2a, Table 2). Although the internal standard was not included in the nested PCR, often it (600 bp amplicon) would be visible in the secondary PCR due to carry over from the primary reaction. DNA sequencing of primary and nested PCR amplicons confirmed the Enc. intestinalis identity of the one 950 bp and all 450 bp products.

Table 2.

Detection of Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Enterocytozoon bieneusi spores in feces of dairy calves using commercial immunofluorescence test or primary and nested polymerase chain reaction directed to ITS1 region of Enc. intestinalis rDNA or the SSU region of Ent. bieneusi rDNA

| Calf no. | Encephalitozoon intestinalis | Enterocytozoon bieneusi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFAa | Primary | Nested | IFAb | Primary | Nested | |

| 1 | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 3 | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 4 | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 5 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| 6 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 7 | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| 8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| 14 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| 15 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

aMicrospora IFA (Waterborne, Inc.)

bBienusiGlo IFA (Waterborne, Inc.)

Similar to Enc. intestinalis PCR, primary and nested Ent. bieneusi PCR proved useful for discriminating between Bienusi-Glo positive and Bienusi-Glo negative fecal samples. Aside from one sample (calf no. 7), all fecals that were Ent. bieneusi-IFA positive gave rise to amplicons of expected size in nested PCR (390 bp) (Table 2). Also, nested PCR was required to generate a detectable product in all, but one of the samples (calf no. 2). In this sample, amplification of the 435 bp target was observed after primary PCR (Fig. 2b, Table 2). DNA sequencing of primary and nested PCR amplicons confirmed the Ent. bieneusi identity of the one 435 bp and all 390 bp products. It remains unclear why the sample from calf no. 7 was positive in both IFA tests, and yet was negative in nested PCR. Inhibition was not observed in both Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi PCRs because the intensity of the internal standard was equal to the water control.

Sensitivity, specificity, and agreement between Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi IFA and PCR

Using the Microspor-FA as the gold standard for detection, Enc. intestinalis nested PCR revealed a sensitivity equal to 85.7% and a specificity equal to 100%. Although primary PCR was useful for generating products for incorporation into the nested PCR, it was, with one exception, not sensitive enough to detect Enc. intestinalis spores in the IFA-positive fecal samples (Table 2). The calculated kappa value (0.865) is considered almost perfect agreement (Watson and Petrie 2010), thus verifying the usefulness of nested PCR to detect Enc. intestinalis spores in calf feces.

A similar conclusion can be made with the Ent. bieneusi nested PCR. Using the Bienusi-Glo as the gold standard for detection, Ent. bieneusi nested PCR revealed a sensitivity equal to 83.3% and a specificity equal to 100%. Again, aside from one sample, nested PCR was required to detect Ent. bieneusi spores in the IFA-positive fecal samples (Table 2). The calculated kappa value (0.857) is considered almost perfect agreement (Watson and Petrie 2010) verifying the usefulness of nested PCR to detect Ent. bieneusi spores in calf feces.

Nearly all PCR methods for detecting Enc. intestinalis and Ent. bieneusi target ribosomal DNA because it exists in multiple copies in the genome (Fedorko et al. 1995; Katzwinkel-Wladarsch et al. 1996; Notermans et al. 2005; Ghoshal et al. 2016). The present study is an improvement on these because it is the first to utilize an internal standard in primary PCR to control for false negative reactions arising from inhibitors in the input sample. A competitor PCR was chosen for this assay because it avoids use of different probes (Musiani et al. 2007) and has been employed by our group and others to detect protozoa and viruses in a variety of matrices (Bergallo et al. 2006; Piña-Vázquez et al. 2008; Jenkins et al. 2015). In all assays involving a competitor molecule, reagents such as primers and dNTPs are added in excess so that the addition of an internal standard does not limit PCR amplification. Also, the nested PCR to detect Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi in calf feces considerably improves the sensitivity of detection. In our opinion, the PCR method described herein is superior to IFA methods because the small size of the spores (~ 2.0 µm) requires considerable expertise to discern positive microsporidia from similarly-sized, often auto-fluorescing objects routinely seen in fecal samples. Identifying a band of expected size after gel electrophoresis of PCR amplicons followed by DNA sequencing is in many ways less ambiguous than epifluorescence microscopy. PCR and DNA sequencing are becoming increasingly routine procedures in diagnostic laboratories. Similar to Cryptosporidium and Giardia, identifying calves shedding Enc. intestinalis or Ent. bieneusi spores may help in improving animal health and transmission to humans in contact with infected calves. One limitation to the assay is that multiple samples will require multiple sets of molecular sieves to process samples in a timely manner. Additional research in isolating spores from fecal slurries is needed to increase the number of samples that can be processed at the same time.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge helpful advice from Monica Santin on microsporidia detection by PCR. This project was solely funded by the USDA-ARS CRIS project “Zoonotic Parasites Affecting Food Animals, Food Safety, and Public Health” (Project No. 8042-32000-100-00-D).

Author’s contributions

MJ designed the experiments, performed the IFA testing of isolated microsporidia, and did statistical analyses of the recovery data. CO performed the cell culture for Enc. intestinalis purification, collected, processed and isolated microsporidian spores from calf feces. CP developed the internal standards, extracted DNA and performed the PCR assays to detect purified microsporidia spores in calf fecal samples.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Alfa Cisse O, Ouattara A, Thellier M, Accoceberry I, Biligui S, Minta D, Doumbo O, Desportes-Livage I, Thera MA, Danis M, Datry A. Evaluation of an immunofluorescent-antibody test using monoclonal antibodies directed against Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis for diagnosis of intestinal microsporidiosis in Bamako (Mali) J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1715–1718. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1715-1718.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa J, Rodrigues AG, Pina-Vaz C. Cytometric approach for detection of Encephalitozoon intestinalis, an emergent agent. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;6:1021–1024. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers PJ, Derks GJ, Gool T, Rietveld FJ, Sauerwein RW. Encephalocytozoon intestinalis-specific monoclonal antibodies for laboratory diagnosis of microsporidiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:282–285. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.282-285.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergallo M, Costa C, Tarallo S, Daniele R, Merlino C, Segoloni GP, Negro Ponzi A, Cavallo R. Development of a quantitative-competitive PCR for quantification of human cytomegalovirus load and comparison with antigenaemia, viraemia and pp67 RNA detection by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Panminerva Med. 2006;48:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholt MA, Lee JH, Tzipori S. Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine: an 18-month survey at a slaughterhouse in Massachusetts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:2595–2599. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2595-2599.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David F, Schuitema AR, Sarfati C, Liguory O, Hartskeerl RA, Derouin F, Molina JM. Detection and species identification of intestinal microsporidia by polymerase chain reaction in duodenal biopsies from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:874–877. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier ES. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 2005;94:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd SE, John D, Eliopolus J, Gerba CP, Naranjo J, Klein R, López B, de Mejía M, Mendoza CE, Pepper IL. Confirmed detection of Cyclospora cayetanesis, Encephalitozoon intestinalis and Cryptosporidium parvum in water used for drinking. J Water Health. 2003;1:117–123. doi: 10.2166/wh.2003.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez FJ, Ditrich O, Palting JD, Smith K. Simple diagnosis of Encephalitozoon sp. microsporidial infections by using a panspecific antiexospore monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:724–729. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.724-729.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorko DP, Nelson NA, Cartwright CP. Identification of microsporidia in stool specimens by using PCR and restriction endonucleases. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1739–1741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1739-1741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal U, Khanduja S, Pant P, Ghoshal UC. Evaluation of immunoflourescence antibody assay for the detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3709–3713. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Weiss LM. Microsporidia: obligate intracellular pathogens within the fungal kingdom. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:1–17. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0018-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on the transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawash Y, Ghonaim MM, Al-Hazmi AS. Internal amplification control for a Cryptosporidium diagnostic PCR: construction and clinical evaluation. Korean J Parasitol. 2015;53:147–154. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RM, Wolk DM, Spencer SK, Borchardt MA. Development of a method for the detection of waterborne microsporidia. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;70:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo F, Castro-Hermida JA, Fenoy S, Mezo M, González-Warleta M, del Aguila C. Detection of microsporidia in drinking water, wastewater and recreational rivers. Water Res. 2011;45:4837–4843. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MC, O’Brien CN, Santin M, Fayer R. Changes in the levels of Cryspovirus during in vitro development of Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:2063–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzwinkel-Wladarsch S, Lieb M, Helse W, Löscher T, Rinder H. Direct amplification and species determination of microsporidian DNA from stool specimens. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:373–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-51.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzwinkel-Wladarsch S, Deplazes P, Weber R, Löscher T, Rinder H. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction with light microscopy for detection of microsporidia in clinical specimens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:7–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01575111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallo MA, Vidoto Da Costa LF, Alvares-Saraiva AM, Rocha PR, Spadacci-Morena DD, Konno FT, Suffredini IB. Culture and propagation of microsporidia of veterinary interest. J Vet Med Sci. 2015;78:171–176. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tate KW, Dunbar LA, Huang B, Atwill ER. Efficiency for recovering Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores from waters by centrifugation and immunofluorescence microscopy. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2003;50:579–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura H, Sodre FC, Bornay-Llinares FJ, Leitch GJ, Navin T, Wahlquist S, Bryan R, Meseguer I, Visvesvara GS. Detection by an immunofluorescence test of Encephalitozoon intestinalis spores in routinely formalin-fixed stool samples stored at room temperature. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2317–2322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2317-2322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A, Stellermann K, Hartmann P, Schrappe M, Fätkenheuer G, Salzberger B, Diehl V, Franzen C. A powerful DNA extraction method and PCR for detection of microsporidia in clinical stool specimens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:243–246. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.2.243-246.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musiani M, Gallinella G, Venturoli S, Zerbini M. Competitive PCR-ELISA protocols for the quantitative and the standardized detection of viral genomes. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2511–2519. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notermans DW, Peek R, de Jong MD, Wentink-Bonnema EM, Boom R, van Gool T. Detection and identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon species in stool and urine specimens by PCR and differential hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:610–614. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.610-614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Vázquez C, Saavedra R, Hérion P. A quantitative competitive PCR method to determine the parasite load in the brain of Toxoplasma gondii-infected mice. Parasitol Int. 2008;57:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R, Kleinz R, Reske-Kunz AB. A method for rapid generation of competitive standard molecules for RT-PCR avoiding the problem of competitor/probe cross-reactions. PCR Methods Appl. 1995;4:371–375. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.6.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigal K, Khurana S, Sharma A, Sehgal R, Malla N. Comparison of staining techniques and multiplex next PCR for diagnosis of intestinal microsporidiosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77:248–249. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stentiford GD, Becnel J, Weiss LM, Keeling PJ, Didier ES, Williams BP, Bjornson S, Kent ML, Freeman MA, Brown MJF, Troemel ER, Roesel K, Sokolova Y, Snowden KF, Solter L. Microsporidia—emergent pathogens in the global food chain. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PF, Petrie A. Method agreement analysis: a review of correct methodology. Theriogenology. 2010;73:1167–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk DM, Schneider SK, Wengenack NL, Sloan LM, Rosenblatt JE. Real-time PCR method for detection of Encephalitozoon intestinalis from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3922–3928. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3922-3928.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]