Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the suitability of using chicken meat affected by wooden breast (WB) myopathy in the production of chicken sausages. Compare the technological and sensory properties of such sausages were compared with those produced from normal (N) breast meat. Three types of chicken sausages were elaborated: 100% containing N chicken meat, 100% of WB chicken meat and 50% N/50% of WB meat. The WB chicken meat presented higher values for pH, L*, moisture, cooking loss, shear force, hardness, chewiness, adhesiveness and gumminess; while WHC and protein content were higher for N chicken meat. N and WB chicken sausages presented similar values of WHC, a*, b* color values, protein content and TBARS. QDA indicated no sensory differences between the three sausage formulations, so did the acceptability and purchase intention. Therefore, WB chicken meat may be used to produce chicken sausages combined or not with N chicken meat. Further studies, however, may be required to investigate the nutritional value and digestibility of WB meat and derived products.

Keywords: Myopathy, Wooden breast, Sausage, Quality, QDA

Introduction

The world production of chicken meat has grown considerably in the last decades, reaching in 2016 the value of 88,718 million tons (APBA 2016). Brazil stands out as the largest exporter of chicken meat with 34% of its production, equivalent to 4.304 million tons; and ranks second as world producer with 14.54% of world-wide production. The success of the production and export of poultry meat result from measures adopted by the industry to meet the market’s needs; such as the production of birds with high growth rate, low feed conversion rate, large carcasses and reduced abdominal fat (Tijare et al. 2016).

While the genetic selection of poultry has allowed reaching large production numbers, it has also led to the onset of myopathies that compromise the quality of the final product, such as visual appearance, water holding capacity, texture and increased fat content (Mudalal et al. 2015; Velleman 2015). The chicken industry has observed the increasing incidence of myopathies in birds, such as wooden breast (WB) in which the Pectoralis major muscle presents partial or integral hardened regions with surface covered by a turbid and viscous liquid and occasional haemorrhages (Sihvo et al. 2014). WB commonly display a greater weight and thickness when compared to normal breast muscles (Dalle Zotte et al. 2014). Up to now, this abnormality has an unknown aetiology though recent reviews have proposed reasonable hypotheses (Petracci et al. 2013a, 2013b). Besides the altered appearance, WB displays impaired technological and nutritional properties (i.e. reduced protein content) and consequently, a reduced acceptability by the consumer (Kuttappan et al. 2013; Mudalal et al. 2015; Mutryn et al. 2015; Sihvo et al. 2014; Soglia et al. 2016). WB myopathy has been reported in Finland, Europe, USA, UK and Brazil. Kindlein et al. (2015) estimated that the occurrence of WB will reach about 39% of birds with up to 35 days of growth. This estimate increases to 89% when they reach 42 days of growth. Considering the Brazilian production of 13.14 million tons in 2015, an average incidence of 11% (unpublished results) and the chicken carcass average price of US $ 2.00 (January 2018), the economic losses caused by WB may reach values of US$ 30 mi.

Due to the impaired sensory attributes, WB does not seem to be appropriate for being marketed as fresh meat and hence, it may be used to produce cooked meat products such as nuggets and sausages (Qin 2013; Mudalal et al. 2015) and chicken emulsions (Sanchez-Brambila et al. 2017). The sausage stands out among processed meat products of high commercial value and may be an option for the use of WB meat. However, Brazilian legislation does not foresee the use of WB chicken meat in the production of processed chicken products. Therefore, the aim of this study was to prepare chicken sausages using N and WB chicken meat and evaluate their technological and sensorial properties, and acceptability and purchasing decision by consumers.

Materials and methods

Normal chicken breast and WB chicken selection

Both male and female Cobb broiler with slaughter age of 44 days were slaughtered in a commercial slaughterhouse owned by Brazilian government. The procedure consisted of the stages of hanging, electronarcosis, stunning, bleeding, scaling, plucking, evisceration, pre-cooling and boning, obeying the criteria established by the law No. 210 of November 10, 1998, of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock and Supply (BRASIL 1998). The breasts were collected and classified in Normal meat (N) and WB meat by visual inspection and palpation (Kuttappan et al. 2013; Sihvo et al. 2014; Bailey et al. 2015). Only breast with WB extreme severity, i.e., high hardness palpable on the surface of the cranial part and appearance of the protuberance in the caudal region were collected and used for sausage production.

Production of emulsion-type chicken sausage

Three different chicken sausages formulations were processed using different chicken breast, namely, normal (N) or affected by the wooden breast abnormality (WB): 100% of N chicken breast, 100% of WB chicken breast and 50% of N chicken breast plus 50% of WB chicken breast (N + WB) (Table 1). The chicken breasts and the chicken fat from a previous rendering process of the carcasses, were ground through a 10 mm diameter mincing plate and minced (Maxmac, Model ZJB750, São Paulo, Brazil) with the additives. The meat mixture was maintained at 4 °C for 6 h and then, was stuffed (Handtmann, Model VF 612, Biberach, Germany) into 32 mm diameter natural casing, packed in a polyetilene plastic bag and stored at − 18 °C for no more than 10 days, until analyses. The whole processing was replicated three times in corresponding independent production batches. Chicken breast and sausages were analysed in quadruplicate for all experimental procedures described as follows, except for color measurements with six replicates.

Table 1.

Fresh chicken sausage formulations elaborated with N chicken breast and WB chicken and their mixture (N + WB)

| Ingredients (%) | N | WB | N + WB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal meat | 52 | – | 26 |

| Wooden breast meat | – | 52 | 26 |

| Chicken Fat | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Water | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Soy protein | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Salt | 1.99 | 1.99 | 1.99 |

| Additives (nitrite salt, phosphates, sodium eritorbate, glutamate monosodium, spices) | 0.510 | 0.510 | 0.510 |

Characterization of N and WB chicken meats and sausages

The N and WB chicken meats and the sausages elaborated with 100% N, 100% WB and 50% N + 50% WB were characterized for pH, water holding capacity (WHC); color parameters L*, a*, b*; cooking loss; moisture content, fat, protein and collagen; Warner–Bratzler shear force (WBSF); texture profile (TPA); thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, TBARS, and warmed-over flavor (WOF).

pH

The pH was determined using the pH-meter (Quimis Aparelhos Científicos Ltda., Model Q400 AS Diadema, SP, Brazil) following AOAC (2000) method, number 981.12.

Whc

Water-holding capacity (WHC) was determined based on the technique described by Hamm (1960). Twenty-four-hour post-mortem samples were collected from the cranial side of the breast meat and cut into 2.0 g (± 0.10) cubes. These were then placed between two filter papers and left under a 10 kg weight for 5 min.

The samples were weighed and WHC was determined by the exudated water weight, via the following formula: 100 − [(Wi − Wf/Wi) × 100], where Wi and Wf are the initial and final sample weights, according to Wilhelm et al. (2010).

Cooking loss

The % cooking loss (CL) was expressed as the percentage of water loss during the cooking procedure. It was measured according to Honikel (1998). The samples were cut into two pieces (80 mm length × 30 mm width × 30 mm thickness) and weighed. The individual slices were transferred to heat resistant plastic bags, and were placed in a continuously boiling water-bath, with the bag opening extending above the water surface. Samples were cooked until they reached an internal temperature of 75 °C. After that, the samples were cooled in an ice bath (1 to 5 °C) until attained 30 °C, and the slices were then taken from the bag, blotted dry and weighed.

The % CL was calculated by the equation: [% CL = [(Pi–Pf)/Pi] × 100, where Pi = sample weight before prior cooking; Pf = sample weigh after cooking.

Instrumental color

The color values of lightness, redness and yellowness L*, a* e b* were measured for the whole breast on the cranial end and for the raw and cooked sausages. The color was measured with Konica Minolta (Model CR-400, Osaka, Japan), in parameters determined by CIE (1986): C illuminate, 8° viewing angle, 10° observer standard angle and specular included. Moisture content, protein and collagen were determined by AOAC (2000) method, items 950.46, 928.08 and 990.26, respectively. The fat content was quantified by the method of Folch et al. (1957).

2-Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS)

TBARS were determined according to Rosmini et al. (1996). Sample absorbances were measured spectrophotometrically (Q798U, UV–Vis Spectrophotometer, Quimis, São Paulo, Brazil). Results were expressed as 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) as mg malonaldehyde (MDA)/kg sample.

Warmed-over flavor (WOF)

WOF was determined according to Soares et al. (2004) with adaptations. Samples were vacuum packed and cooked in water bath until reaching an internal temperature of 75 °C, and then stored at 4 °C for 48 h under fluorescent light. After that, the samples were re-heated in water bath at 85 °C for 15 min, and left to cool to room temperature; the WOF which resulted from this procedure was then determined by measuring the TBARS numbers, following the technique described by Rosmini et al. (1996).

Texture analyses

Warner–Bratzler shear force (WBSF) assessment was performed in a TA XT-2i texture-meter (Stable Microsystems, Godalming, Surrey, UK). Samples, raw breast chicken and chicken sausages) were prepared in slices of dimensions 2 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm (thickness × length × width). In the analyses, samples were cut with a Warner–Bratzler blade in a direction perpendicular to the muscle fibres. Analyses were performed in quadruplicate in each processing batch. Hardness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, flexibility, gumminess, chewiness and resilience were determined in the chicken breasts, N and WB, cut in dimensions 2 mm × 20 mm x 20 mm (thickness × length × width). The sausages were cooked at 75 °C, cooled and cut 20 mm wide. These measurements were determined by TA-TX2i coupled with 6 mm cylindrical probe (P/25) under the following conditions: pre-test speed: 2.0 mm/s; test speed: 2.0 mm/s; post-test velocity: 5.0 mm/s; Compression distance 8.0 mm and firing force: 5 g. The WBSF and TPA measurements were analyzed using the Texture Expert software for Windows 1.20 (Stable Micro Systems\TE32L\version 6.1.4.0 England) and the results were evaluated according to statistical planning.

Sensory analysis of chicken sausages

The sausages were evaluated using a quantitative-descriptive analysis (QDA) method by a trained panel composed of 7 assessors (students of the PPGCTA of Federal University of Paraiba, Brazil). The tests were authorized by the Ethics and Research with Human Beings Committee (CAAE 67651917.4.0000), meeting the ethical and scientific requirements from Resolution number 466, National Health Council (BRASIL 2012). Eleven attributes were evaluated, and the tests were conducted only after the verification of the microbiological parameters established by Brazilian legislation (BRASIL 2001). The sausages were grilled in an electric grill and monitored with a thermocouple (Hanna Instruments, HI 935005, Romania), until the internal temperature reached 75 °C (Soultos et al. 2008). The sausages were cooled down for 3 min at room temperature and then were cut into 2 cm rectangles, each sample was evaluated separately, and served on glass plates along with a glass of water (150 ml) and unsalted biscuit to follow the protocol of rinsing between the samples. A total of 3 sessions were done in a sensory panel room with booths equipped with white fluorescent light; the order of the sample was randomized. Eleven attributes grouped in appearance, odor, flavor and texture were evaluated using a 9 cm linear unstructured quantitative scale with “little” to “much” extremes for all attributes (ABNT 1998).

Acceptability and purchase intention analyses were conducted with 200 consumers (non-trained assessors) according to the methodology described by Stone and Sidel (1993) and Meilgaard et al. (1999). The acceptability test was applied using a hedonic scale of five points, ranging from 5 (“I like it very much”) to 1 (“I dislike it very much”). Consumers evaluated sausages for appearance, overall acceptance, aroma, taste and texture. The purchase intention test was performed simultaneously to the acceptability test. For this test, consumers expressed their opinion using a five-points scale, ranging from 5 (“I would certainly buy this product”) to 1 (“I would certainly not buy this product”). Acceptability and purchase intention rates (expressed in %) refer to the percentage of consumers who expressed their acceptance and willingness to purchase the product, respectively, by scoring the sample with at least 3 points (“I like” and “I would probably purchase” in the acceptability and purchase intention tests, respectively).

Statistical analysis

The results obtained by the physical–chemical measurements (moisture, fat, protein, collagen, TBARS, WOF, color and pH) and technological (WHC, cooking loss, WBSF and TPA) measurements of WB and N chicken meats were compared by applying the student´s T test, using the software Assistat version 7.7 (Silva and Azevedo 2016). Data obtained from analyses of the sausages elaborated with WB and N meats were evaluated by one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and subsequently with Tukey tests (SAS 2014). Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Physico-chemical characteristics of N and WB chicken breasts

WB meat was significantly different (P < 0.05) to N chicken breast in terms of moisture and protein contents, pH, L*, WHC and cooking loss (Table 2). The WB chicken presented an increased moisture content, which is in agreement with the data described by Soglia et al. (2016a, b). According to Sihvo et al. (2014), the increased moisture content in WB may also be attributed to the presence of oedema and fluid in the muscle due to inflammatory processes. In WB chicken, the protein content was significantly lower than in the N counterparts, which is consistent with results reported by Mudalal et al. (2015) and Soglia et al. (2016b). According to these authors, the difference in the protein content may be due to the successive degeneration and regeneration of muscle tissue in WB chicken, resulting in the replacement of myofibrillar proteins with connective tissue and extracellular material. However, significant differences were not observed (Table 2) in collagen content between WB and N chicken breast. The reduction in the content of muscle protein may be attributed to the lower WHC in WB chicken (Petracci et al. 2013a, 2013b; Dalle Zotte et al. 2017). According to Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan (2005) changes in the intracellular architecture of muscle may also play a role in myofibril’s ability to retain water.

Table 2.

Physico-chemical and texture parameters of N and WB chicken breasts

| Parameters | N | WB | Sig (p)1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.79 ± 0.12 | 5.91 ± 0.15 | ** |

| WHC (%) | 33.84 ± 1.66 | 17.3 ± 0.27 | ** |

| Cooking loss(%) | 15.71 ± 0.68 | 25.72 ± 3.10 | ** |

| L* | 50.43 ± 2.06 | 53.78 ± 1.55 | ** |

| a* | 0.98 ± 0.65 | 2.12 ± 1.28 | ns |

| b* | 5.19 ± 1.67 | 6.31 ± 0.78 | ns |

| Moisture (g/100 g) | 72.53 ± 0.14 | 74.91 ± 0.20 | ** |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 3.42 ± 0.06 | 3.51 ± 0.21 | ns |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 21.77 ± 0.32 | 20.92 ± 0.37 | * |

| Collagen (g/100 g) | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | ns |

| SF (N) | 23.89 ± 4.42 | 30.53 ± 2.82 | ** |

| Hardness (N) | 26.82 ± 4.56 | 39.44 ± 5.40 | ** |

| Adhesiveness (g/sec) | − 5.84 ± 1.05 | − 8.02 ± 1.87 | * |

| Springiness | 0.62 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | ns |

| Cohesiness | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | ns |

| Gumminess | 16.40 ± 2.91 | 22.82 ± 3.74 | ** |

| Chewiness | 10.30 ± 2.02 | 13.40 ± 2.40 | ** |

| Resilience | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | ns |

*p ≤ 0.05 there is a significant 5% difference between the products; ** p ≤ 0.01 there is a significant difference of 1% between the products; ns there is no significant difference between products

The mechanisms implicated in the the increase of the pH in WB chicken are not fully clear (Mudalal et al. 2015). It may be caused by the severe degeneration of muscle fibers in WB meat, which exhibits a reduction in their glycogen content (Soglia et al. 2016b) or a modification in the acidification mechanisms during the post-mortem period. Besides, the higher pH in WB chicken may be associated to its higher weight when compared to N chicken breast (Mudalal et al. 2015; Charttejee et al. 2016; Dalle Zotte et al. 2017). A negative correlation between the muscle breast size and glycogen storage was observed by Le Bihan et al. (2008). In addition, Dalle Zotte et al. (2017) reported that a larger chicken breast may have a lower glycolytic potential resulting in a higher final pH.

Only L* value presented significant differences between the breasts under study, with this parameters being higher in the WB samples than the N chicken breast. This characteristic may be associated to the muscle degeneration occurred in WB chicken. The muscle presents a lower volume of myofibrillar proteins, resulting in a greater ability to scatter light due to the greater spacing between the protein filaments (Feiner 2016). Sihvo et al. (2014) observed that WB chicken displayed whitish regions with or without white stripping and bleeding signs. However, the color characterization of WB chicken is still diverging. Charttejee et al. (2016) observed significant differences only for a* value, while Dalle Zotte et al. (2017) found significant differences for all parameters (L*, a*, b*) and Sanchez-Brambila et al. (2017) reported no significant differences between N and WB samples.

Cooking loss and WHC (Table 2) displayed by both WB and N chicken breasts, were similar to those reported by Dalle Zotte et al. (2014); Mudalal et al. (2015); Trocino et al. (2015); Charttejee et al. (2016) and Sanchez-Brambila et al. (2017). WHC of WB chicken breast was lower, when compared to N chicken breast, leading to higher cooking losses. The increase in cooking loss in WB chicken may be attributed to modifications that may occur in the membrane of muscle fibres, affecting its integrity. WB commonly presents a higher proportion of extracellular water and defects in myofibrillar or sarcoplasmic proteins that could easily lead to protein denaturation and oxidation as well as changes in some chemical components that may contribute to poor WHC and water loss (Qin 2013; Mudalal et al. 2015; Soglia et al. 2016a, 2016b; Estévez 2015).

Significant differences were found between N and WB chicken breasts for their texture properties as measured by WBSF and TPA. The WBSF of WB samples was 28% greater than that of N chicken breasts. These differences were possibly caused by accumulation of interstitial connective tissue (Sihvo et al. 2014). The higher WBSF in WB chicken is consistent with the data published by Mudalal et al. (2015); Charttejee et al. (2016); Sanchez-Brambila et al. (2017); and Dalle Zotte et al. (2017). The TPA also revealed significant differences between samples. WB chicken breasts were harder (39.44 WB and 26.82 N), showed higher adhesiveness (− 8.02 WB vs − 5.84 N), gumminess (22.82 WB vs 16.40 N) and chewiness (13.4 WB vs 10.3 N) than N breast muscles. However, springiness, cohesiveness, and resilience of WB and N chicken breasts presented no significant differences (p > 0.05). Mudalal et al. (2015) and Charttejee et al. (2016) also observed higher hardness in WB chicken compared to N ones.

Physico-chemical characteristics of sausages

The three formulations of sausages under study (N, WB and WB + N) presented significant differences (P < 0.05) for several physico-chemical parameters (Table 3). The moisture content was higher in sausages elaborated with WB, which was consistent with the composition of the raw material. The protein content in WB sausages was lower than that in N and WB + N sausages, also following the tendency of the raw material. Sausages produced from WB and WB + N had higher collagen content than the N sausages. WHC of WB sausages was lower than that of the sausages from the other formulations. These results are compatible with those found in the raw material and may be attributed to the fibrosis and lipidosis that occurs in WB chicken (Soglia et al. 2016b). It is worth noting that combining 50% N breast meat with the same share of breast affected by WB allows to compensate the impaired WHC of the latter. In meat products, WHC negatively affects the palatability due to changes in texture and juiciness (Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan 2005). However, as explained in due course, the differences between sausages for this parameter, though significant, were quantitatively restricted and had no impact on the sensory properties of the sausages. In fact, no significant differences were found between types of sausages for the cooking loss. The apparent lack of consistency between WHC and cooking loss measurements may be explained by the fact that both measurements are based on different approaches and hence, the fundamentals behind the WHC of myofibrillar proteins may not be the same as those governing the mechanisms of cooking loss in which samples are subjected to the effect of high temperatures. In these more severe conditions, all formulations displayed a similar behaviour, emphasizing the feasibility of using WB samples for the production of fresh and cooked chicken sausages.

Table 3.

Physico-chemical parameters of fresh chicken sausages elaborated with N, WB chicken breasts and their mixture (N and WB)

| Parameter | N | WB | N + WB | Sig (p)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.20 ± 0.02 | 6.30 ± 0.02 | 6.30 ± 0.02 | ns |

| WHC (%) | 29.69 ± 3.24ab | 27.29 ± 2.14b | 32.98 ± 0.64a | * |

| Cooking Loss(%) | 7.13 ± 1.31 | 9.53 ± 2.38 | 7.37 ± 1.87 | ns |

| L* raw | 69.78 ± 5.32 | 72.68 ± 3.11 | 67.87 ± 2.44 | ns |

| a* raw | 4.16 ± 0.92b | 3.95 ± 0.53b | 4.93 ± 0.60a | * |

| b* raw | 20.67 ± 2.62ab | 21.12 ± 1.91a | 19.22 ± 1.40b | * |

| L* cooked | 74.94 ± 1.67 | 75.55 ± 0.76 | 74.12 ± 2.71 | ns |

| a* cooked | 3.71 ± 0.82 | 3.77 ± 1.24 | 3.65 ± 0.88 | ns |

| b* cooked | 14.40 ± 1.59 | 14.60 ± 0.45 | 13.60 ± 0.66 | ns |

| Moisture (g/100 g) | 71.39 ± 0.36b | 73.43 ± 0.66a | 73.21 ± 0.88a | * |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 7.36 ± 0.89 | 7.55 ± 1.32 | 6.41 ± 1.04 | ns |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 16.31 ± 0.88a | 16.05 ± 0.31b | 17.48 ± 0.54a | * |

| Collagen (g/100 g) | 0.34 ± 0.01c | 0.44 ± 0.00b | 1.03 ± 0.01a | * |

| TBARS raw (mg MDA/kg) | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | ns |

| TBARS cooked (mg MDA/kg) | 0.38ab ± 0.03 | 0.44a ± 0.05 | 0.26c ± 0.02 | * |

| WOF (mg MDA/kg) | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | ns |

1 * p ≤ 0.05 there is a significant difference of 5% between the three formulations; ns there is no significant difference between the formulations

TBARS values (Table 3) indicated low extent of lipid oxidation in the sausages under study (< 0.20 mg MDA/kg). The addition of food preservatives could have contributed to keep oxidative reactions under control. According to Campo et al. (2006) and Greene and Cumuze (1982), rancid flavor may be noticed by consumers when TBARS values are between 2-3 mg/kg of product. Increases in the TBARS values of the cooked sausages probably resulted from changes in the protein membrane structure, also from the iron release of the carrier protein, which reacts with the oxygen thus accelerating the rate of oxidation (Adeyemi and Olorunsanya 2012). Significant differences were found between cooked samples but the levels were still far below the threshold considered to be perceived by consumers (Campo et al. 2006). Consistently, WOF in the sausages was also low (< 0.60 mg MDA/kg) and presented no significant differences between the three formulations.

Sensory characteristics of sausages

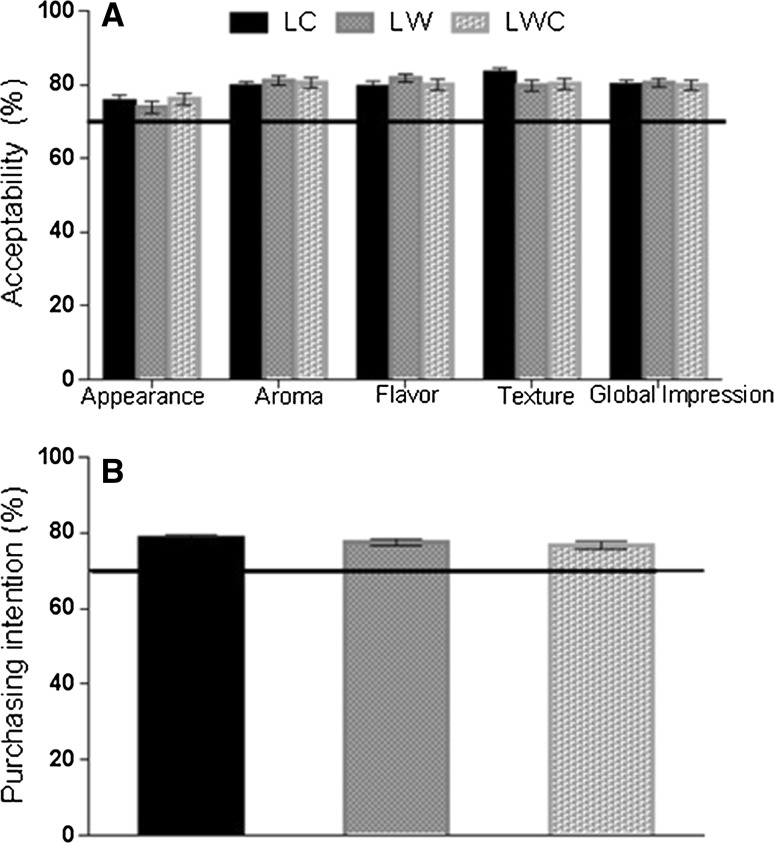

The microbiological counts of the sausages elaborated with N, WB and WB + N chicken meats were within the accepted range established by the Brazilian legislation (BRASIL 2001). The assessors noticed no difference between the three formulations of sausages during QDA (Table 4), except for “pink color” attribute (P < 0.05). The sausages produced with WB chicken meats presented lower intensity of pink color when compared with the others. Grilled chicken aroma and flavor scored values between 2.93 and 4.65, indicating a moderated intensity. The rancid aroma scored low values which is in accordance with the results obtained from TBARS and WOF (Table 3). Juiciness (5.43 to 5.89), hardness (3.87 to 5.20), cohesiveness (3.66 to 4.41) and chewiness (5.43 to 3.92) indicated that the texture of the sausages was not affected by the type of meat used (WB, N or WB + N). It is reasonable to hypothesized that the comminution of the breast meat contributed to eliminating the relevant impact of the myopathy (fibre degeneration, fibrosis) on the texture of the fresh muscle. The QDA results show the potential of WB chicken meats as ingredients in the production of sausages, since the trained assessors were not capable of detecting significant differences between the formulations (N, WB and WB + N). In good agreement with the QDA, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed for the instrumental measurements of texture. WBSF, hardness, adhesiveness, springiness, cohesiveness, gumminess, chewiness and resilience were similar between the three formulations. The parameters evaluated in the acceptability test by consumers (Fig. 1a) revealed no significant differences between formulations (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Sensory (QDA) and texture profile of fresh chicken sausages elaborated with N, WB chicken breasts and their mixture (N + WB)

| Attributes | N | WB | N + WB | Sig (p)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pink colour | 1.63 ± 0.24a | 1.48 ± 0.25b | 2.85 ± 0.61a | * |

| Grilled chicken aroma | 3.92 ± 1.59 | 3.97 ± 1.28 | 4.04 ± 1.51 | ns |

| Rancid aroma | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | ns |

| Grilled chicken aroma | 2.93 ± 1.13 | 3.92 ± 1.61 | 4.65 ± 1.42 | ns |

| Salt Flavour | 4.06 ± 1.07 | 4.13 ± 1.27 | 4.17 ± 1.04 | ns |

| Hardness | 3.87 ± 0.82 | 4.45 ± 0.71 | 5.20 ± 1.24 | ns |

| Juiciness | 5.89 ± 0.78 | 5.43 ± 0.80 | 5.72 ± 0.79 | ns |

| Cohesiveness | 3.66 ± 1.11 | 4.41 ± 1.09 | 3.71 ± 0.86 | ns |

| Chewiness | 3.75 ± 1.01 | 3.92 ± 0.82 | 3.83 ± 0.76 | ns |

| Fibrosity | 5.02 ± 0.88 | 5.29 ± 0.79 | 4.44 ± 1.15 | ns |

| Oiliness | 3.88 ± 1.20 | 4.85 ± 1.40 | 4.41 ± 1.89 | ns |

| WBSF (N) | 122.95 ± 11.65 | 144.56 ± 17.72 | 122.56 ± 21.56 | ns |

| Hardness (N) | 41.55 ± 3.37 | 41.57 ± 3.06 | 38.19 ± 4.21 | ns |

| Adhesiveness (g/s) | − 2.97 ± 1.84 | − 3.78 ± 1.45 | − 3.69 ± 0.95 | ns |

| Springiness | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | ns |

| Cohesiveness | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | ns |

| Gumminess | 25.99 ± 2.26 | 28.19 ± 2.29 | 26.51 ± 3.24 | ns |

| Chewiness | 23.55 ± 2.34 | 25.43 ± 1.92 | 23.43 ± 3.10 | ns |

| Resilience | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | ns |

1*p ≤ 0.05 there is a significant difference of 5% between the three formulations; ns there is no significant difference between the formulations

Fig. 1.

Acceptability test (A) and Purchase intention (B) of fresh chicken sausages elaborated with N (LC), WB (LW) chicken breasts and their mixture (LWC)

The acceptance rate of appearance, aroma, taste, texture and global impression were up to 70%, which indicates that the samples were sensory accepted. The texture presented a good overall acceptance, scored in 7.2 (“I like moderately”). The “pink color” presented a good acceptance rate, up to 73% for the three types of sausages. The purchase intention rate (Fig. 1B) showed an acceptance rate up to 76% for all formulations, and an average score of 3.9 in a hedonic scale from 0 to 5, approaching “would probably buy.”

Conclusion

The chicken breasts affected by WB myopathy presented a great potential to be used in the preparation of sausages, since the physical–chemical and sensory parameters of the product were not influenced by this condition. The QDA did not discriminate the three formulations of sausages. In addition, the acceptability and purchase intention tests indicated that regular consumers approved the sausages, regardless of the type of meat (N, WB or WB + N) used in their formulation. The results showed that chicken WB may be used in the industry to prepare processed products, such as sausages combined or not with the N chicken breast, thus reducing the economic losses caused by wooden breast myopathy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Guaraves Company, in the person of its Technical Director Mr. Arnoud C. S. Neto, who made possible the present research. This work was supported by CNPq (Project 430832/2016-8; grant scholarship to the researcher MSM, EII); CAPES (for the scholarship granted to the students TCR and LMC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ABNT Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (1998) NBR 14140: alimentos e bebidas—análise sensorial—teste de análise qualitativa descritiva (ADQ)

- ABPA Associação Brasileira de Proteína Animal (2016) Relatório Anual http://abpa-br.com.br/setores/avicultura/publicacoes/relatorios-anuais. Accessed 28 October 2017

- Adeyemi KD, Olorunsanya AO. Comparative analysis of phenolic composition and antioxidant effect of seed coat extracts of four cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) varieties on broiler meat. Iran J Appl Animl Scie. 2012;2:343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists . Official methods of analysis of AOAC. 17. Washington, DC, USA: AOAC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RA, Watson KA, Bilgili SF, Avendano S. The genetic basis of pectoralis major myopathies in modern broiler chicken lines. Poult Sci. 2015;94:2870–2879. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil (1998) Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Portaria no 210, de 10 de novembro de 1998. Aprova o regulamento técnico da inspeção tecnológico e higiênico-sanitária de carne de aves. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF

- Brasil (2001) Ministério da Saúde. Resolução RDC nº 12, de 02 de janeiro de 2001. Regulamento técnico sobre padrões microbiológicos para alimentos. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasil, 7-E, 46–53

- Brasil (2012) Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n° 466. Diretrizes e Normas regulamentadoras de pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasil, p. 59

- Campo MM, Nute GR, Hughes SI, Enser M, Wood JD, Richardson RI. Flavour perception of oxidation in beef. Meat Sci. 2006;72:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charttejee D, Zhuang H, Browker BC, Rincon AM, Sanchez-Brambila G. Instrumental texture characteristics of broiler pectoralis major with the wooden breast condition. Poult Sci. 2016;95:2449–2454. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission Internacionale de l’Eclairage (1986) CIE Publication 15.2. Vienna

- Dalle Zotte A, Cecchinato M, Quartesan A, Bradanovic J, Tasoniero G, Puolanne E. How does “Wooden Breast” myodegeneration affect poultry meat quality? Arch Latinoamer Prod Anim. 2014;22:476–479. [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Zotte A, Tasoniero G, Puolanne E, Remignon H, Cecchinato M, Catelli E, Cullere M. Effect of “Wooden Breast” appearance on poultry meat quality, histological traits, and lesions characterization. Anim Sci. 2017;62(2):51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez M. Oxidative damage to poultry: from farm to fork. Poult Sci. 2015;94(6):1368–1378. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner G. Meat products handbook: practical science and technology. Cambridge: Inglaterra; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane-Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;22:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene BE, Cumuze TH. Relationship between TBA numbers and inexperienced panelists’ assessments of oxidized flavor in cooked beef. J Food Sci. 1982;47(1):52–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb11025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm R. Biochemistry of meat hydration. Adv Food Res. 1961;10(2):355–463. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2628(08)60141-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honikel KO. Reference methods for the assessment of physical characteristics of meat. Meat Sci. 1998;49(4):447–457. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(98)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff-Lonergan E, Lonergan SM. Mechanisms of water-holding capacity of meat: the role of post mortem biochemical and structural changes. Meat Sci. 2005;79(1):194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindlein LLM, Lorscheitter TZ, Ferreira R, Sesterhen S, Rauber P, Soster S, Vieira Occurrence of white striping and wooden breast in broiler breast fillets slaughtered at 35 and 42 d of age. Poult Sci. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Kuttappan VA, Shivaprasad HI, Shaw DP, et al. Pathological changes associated with white striping in broiler breast muscles. Poult Sci. 2013;92(2):331–338. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bihan Duval E, Debut M, Berri CM, Sellier N, Santelhoutellier V, Jego Y, Beaumont C. Chicken meat quality: genetic variability and relationship with growth and muscle characteristics. BMC Genet. 2008;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard M, Civille GV, Carr BT. Sensory evaluation techniques. 3. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mudalal S, Lorenzi M, Soglia F, Cavani C, Petracci M. Implications of White striping and Wooden breast abnormalities on quality traits of raw and marinated chicken meat. Anim. 2015;9(4):728–734. doi: 10.1017/S175173111400295X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutryn MF, Brannick EM, Fu W, Lee WR, Abasht B. Characterization of a novel chicken muscle disorder through differential gene expression and pathway analysis using RNA-sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1623-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petracci M, Mudalal S, Bonfiglio A, Cavani C. Occurrence of white striping and its impact on breast meat quality in broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2013;92(6):1670–1675. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petracci M, Soglia F, Madruga M, Carvalho L, Ida E, Estévez M (2013) Wooden-breast, white striping and spaghetti meat: causes, consequences and consumer perception of emerging broiler meat abnormalities. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 10.1111/1541-4337.12431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Qin N (2013) The utilization of poultry breast muscle of different quality classes. PhD Thesis: Department of Food and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki

- Rosmini, Perlo F, Pérez-Alvarez JA, Pagin-Moreno MJ, Gago-Gage A, Lopez-Santoveii F, Aranda-Cata V. TBA test by an extractive method applied to ‘paté. Meat Sci. 1996;42(1):103–110. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(95)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Brambila G, Chatterjee D, Bowker B, Zhuang H. Descriptive texture analyses of cooked patties made of chicken breast with the woody breast condition. Poult Sci. 2017;96(9):3489–3494. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2014) SAS/STAT Guide for Personal Computers. Version 11.0 ed. Cary, NC: SAS Inst.Inc

- Sihvo HK, Immonen K, Puolanne E. Myodegeneration with fibrosis and regeneration in the pectoralis major muscle of broilers. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(3):619–623. doi: 10.1177/0300985813497488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FAS, Azevedo CAV. The Assistat Software Version 7.7 and its use in the analysis of experimental data. Afric J Agric Res. 2016;11(39):3733–3740. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2016.11522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soares AL, Olivo R, Shimokomaki M, Ida EI. Synergism between dietary vitamin E and exogenous phytic acid in prevention of warmed-over flavour development in chicken breast meat, Pectoralis major m. Br Arch Biol Technol. 2004;47(1):57–62. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132004000100008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soglia F, Laghi L, Canonico LC, Cavani C, Petracci M. Functional property issues in broiler breast meat related to emerging muscle abnormalities. Food Res Int. 2016;89(3):1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soglia F, Mudalal S, Barbini E, Di Nunzio M, Mazzoni M, Sirri F, Cavani C, Petracci M. Histology, composition, and quality traits of chicken Pectoralis major muscle affected by wooden breast abnormality. Poult Sci. 2016;95(3):651–659. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soultos N, Tzikas Z, Abrahim A, Georgantelis D, Ambrosiadis I. Chitosan effects on quality properties of Greek style fresh pork sausages. Meat Sci. 2008;80(4):1150–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone H, Sidel J. Sensory evaluation practices. New York: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tijare VV, Yang FL, Kuttappan VA, Alvarado CZ, Coon CN, Owens CM. Meat quality of broiler breast fillets with white striping and woody breast muscle myopathies. Poult Sci. 2016;95(9):2167–2173. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocino A, Piccirillo A, Birolo M, et al. Effect of genotype, gender and feed restriction on growth, meat quality and the occurrence of white striping and wooden breast in broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 2015;94(12):2996–3004. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velleman SG. Relationship of skeletal muscle development and growth to breast muscle myopathies: a review. Av Dis. 2015;59(4):525–531. doi: 10.1637/11223-063015-Review.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm AE, Maganhini MB, Hernández-Blazquez FJ, Ida EI, Shimokomaki M. Protease activity and the ultrastructure of broiler chicken PSE (pale, soft, exudative) meat. Food Chem. 2010;119(3):1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.08.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]