Abstract

Summary

The use of gastro-resistant risedronate, a convenient dosing regimen for oral bisphosphonate therapy, seems a cost-effective strategy compared with weekly alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in France.

Introduction

Gastro-resistant (GR) risedronate tablets are associated with improved persistence compared to common oral bisphosphonates but are slightly more expensive. This study assessed its cost-effectiveness compared to weekly alendronate and generic risedronate for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in France.

Methods

A previously validated Markov microsimulation model was used to estimate the lifetime costs (expressed in €2017) per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) of GR risedronate compared with weekly alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment. Pooled efficacy data for bisphosphonates derived from a previous meta-analysis were used for all treatment options, and persistence data (up to 3 years) were obtained from a large Australian longitudinal study. Evaluation was done for high-risk women 60–80 years of age, with a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score ≤ − 2.5 and/or prevalent vertebral fractures.

Results

In all of the simulated populations, GR risedronate was cost-effective compared to alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment at a threshold of €60,000 per QALY gained. In women with a BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures, the cost per QALY gained of GR risedronate compared to alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment falls below €20,000 per QALY gained. In women aged 75 years and older, GR risedronate was even shown to be dominant (more QALYs, less costs) compared to alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment.

Conclusion

This study provides the first economic results about GR risedronate, suggesting that it represents a cost-effective strategy compared with weekly alendronate and generic risedronate for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in France.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Economic evaluation, Osteoporosis, Risedronate, Treatment

Introduction

Oral bisphosphonates (especially alendronate and risedronate) remain the standard of care for the treatment of osteoporosis. Poor adherence to oral bisphosphonates due to instructions for use and gastrointestinal side effects represents however a concern [1]. Approximately 75% of women who initiate oral bisphosphonates were shown to be non-adherent within 1 year and 50% discontinued therapy by this time [2], leading to a substantial decrease of the potential benefits of the drugs [3]. All oral bisphosphonates require patients to follow strict dosing instructions to derive the full benefits, i.e., the intake of the drug on an empty stomach at least 30 to 60 min before the first food, drink, or other medication of the day [4].

Recently, weekly gastro-resistant (GR) risedronate tablets (also called delayed-release formulation of risedronate) were developed to facilitate its use and decrease potential side effects with elimination of the need for fasting without affecting its bioavailability and efficacy. This formulation provides thus a more convenient dosing regimen for oral bisphosphonate therapy, allowing patients to take their weekly risedronate immediately after breakfast. Clinical studies have confirmed that 35 mg GR risedronate is similar in efficacy and safety than risedronate 5 mg daily [4, 5].

GR risedronate tablets are thus expected to be associated with improved persistence compared to common oral bisphosphonates, but they are also slightly more expensive. Considering the limited healthcare resources available, it has become important for decision makers to allocate healthcare resources efficiently [6], and the question whether risedronate GR is cost-effective or not compared with the most relevant alternative treatments (i.e., weekly alendronate and generic risedronate) is thus highly relevant. Economic evaluations that compare interventions in terms of costs and outcomes are nowadays increasingly important and used by decision makers, especially for pricing and reimbursement decisions.

The aim of this study was therefore to assess the cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate compared to weekly alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in France.

Methods

A previously validated Markov microsimulation model [7] was used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate compared to weekly alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment from the French payer perspective. The model was built up using TreeAge Pro 2017 (TreeAge Pro Inc., Williamston, MA, USA) and adheres to the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement [8]. A description of the model is provided here below; most data are included in Table 1 and additional information could be found in previous studies [7, 17], including an analysis that assessed the public health impact and economic evaluation of vitamin D–fortified dairy products for fracture prevention in France [18].

Table 1.

Incidence of fractures, costs, utilities, and treatment effects used in the model

| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| Incidence of fracture (rate/100) [9, 10] | |

| Hip | 0.055 (60–64 years), 0.098 (65–69 years), 0.199 (70–74 years), 0.462 (75–79 years), 0.915 (80–84 years), 2.312 (85+) |

| Vertebral | 0.097 (60–64 years), 0.142 (65–69 years), 0.280 (70–74 years), 0.450 (75–79 years), 0.575 (80–84 years), 1.087 (85+) |

| Wrist | 0.207 (60–64 years), 0.238 (65–69 years), 0.356 (70–74 years), 0.451 (75–79 years), 0.573 (80–84 years), 0.986 (85+) |

| Other | 0.211 (60–64 years), 0.335 (65–69 years), 0.563 (70–74 years), 0.973 (75–79 years), 1.557 (80–84 years), 3.884 (85+) |

| Direct fracture cost (€2017) [9, 11, 12] | |

| Hip, first 6 months | 12,081 |

| Hip, yearly long-term | 3387 (< 70 years)–6807 (≥ 70 years) |

| CV, first 6 months | 5929 |

| Wrist, first 6 months | 2144 |

| Other, first 6 months | 5778 |

| Health state utility values [13, 14] | |

| General population | 0.766 |

| Hip (1st year/ subs. years) | 0.55 (0.53–0.57)/0.86 (0.84–0.89) |

| CV (1st year/ subs. years) | 0.68 (0.65–0.70)/0.85 (0.82–0.87) |

| Wrist (1st year/ subs. years) | 0.83 (0.82–0.84)/0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

| Other (1st year/ subs. years) | 0.91 (0.88–0.94)/0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

| Treatment effects of oral bisphosphonates (relative risk of fracture) [15] | |

| Hip | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) |

| CV | 0.61 (0.50–0.75) |

| Wrist | 0.68 (0.43–1.08) |

| Other | 0.76 (0.64–0.91) |

| Drug cost (for 12 weeks) [16] | |

| GR risedronate | 49.04 |

| Generic risedronate | 31.67 |

| Alendronate | 46.28 |

| GP visit | 23 |

| BMD measurement | 39.96 |

CV, clinical vertebral; subs., subsequent; y, years

Model structure

A Markov microsimulation model was used to allow tracking patient characteristics and individual disease histories (e.g., fractures and residential status) and avoid unnecessary transition restrictions. The model health states were no fracture, death, hip fracture, clinical vertebral fracture, wrist fracture, and other fracture. The “other fracture” state includes other osteoporotic fractures as defined by the IOF-EFPIA report [9]. We used a lifetime horizon and a 6-month cycle. Patients could experience multiple fractures at the same site or multiple sites. Discount rates of 3% for both costs and health benefits were used.

Populations

Analyses were conducted for postmenopausal women aged 60 to 80 years with bone mineral density (BMD) T-score ≤ − 2.5 and/or prevalent vertebral fractures, in line with current reimbursement conditions for oral bisphosphonates in France.

Fracture risk

Incidence of hip fractures in the general French population was derived from the study of Briot et al. [10] using data from the year 2013. Since this study only reported incidence data for large age groups (e.g., 60–74 years), an adjustment was made based on the IOF-EFPIA report [9] to estimate a 5-year incidence rate and thus take into account that fracture risk is increasing over time. As no data for the incidence of other osteoporotic fractures (i.e., clinical vertebral, wrist, and other fractures) are available in France, we applied the age-specific ratio incidence from other countries in line with the methodology used by the IOF-EFPIA report [9].

Initial fracture probabilities were then adjusted to accurately reflect the fracture risk in the target population in comparison with that of the general population using previously validated methods [19, 20]. Fracture risk was also adjusted when a new fracture occurred during the simulation process, as previously done [17].

Baseline mortality data for the general population was derived from the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) for the years 2013–2015 [21]. We further assumed an increased mortality after hip fracture and clinical vertebral fracture in line with previous studies [17]. Because excess mortality may also be attributable to comorbidities, we further took into account that only 25% of the excess mortality following fractures was attributable to the fractures themselves [22, 23].

Fracture cost

We used a healthcare perspective for the cost estimation. The costs of hip and wrist fractures were derived from the study of Bouee et al. [11]. The cost of clinical vertebral fracture was derived from a previous cost-effectiveness analysis in France [12], and the cost of other fractures was quantified relative to hip fracture in line with the assumption used in the IOF-EFPIA report [9]. All costs were expressed in €2017 and adjusted using the national price index (health index).

Hip fractures are also associated with long-term costs. These long-term costs were based on the proportion of patients being admitted in nursing home following the fracture. Based on the study of Drame et al. [24], 20.1% of patients were institutionalized after a hip fracture in French population aged above 75 years. For patients aged between 60 and 74 years, we conservatively assumed that only 10% were institutionalized in line with international studies [9]. The annual cost of living in nursing home that was reduced by 10% to take into account that patients could have been institutionalized later in their life was estimated at €37,629 [25]. Non-hip fractures were not associated with long-term costs.

We also incorporated a higher cost for a recurrent fracture at the same type within the model, in line with a recent study suggesting that patients who experienced a subsequent fracture had significantly higher healthcare costs than patients with a first fracture [26]. The proportion factor (1.68) derived from the study of Weaver et al. [26] was thus applied.

Utility values

Baseline utility value in the general French population was estimated at 0.766 [13]. The effects of fractures on utility were derived from the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (ICUROS) study [14]. This study is the largest study assessing the quality of life of patients with fractures from 11 countries including 2808 patients. Since other fractures were not included in the ICUROS study, we used estimate from a previous systematic review [27]. An additional effect on utility after multiple fractures was modeled as previously done [17].

Treatment effects

In the absence of studies suggesting a clear and significant difference in treatment effects between oral bisphosphonates (alendronate and risedronate) [28], the National Institute for Clinical Health and Excellence (NICE) in the UK has suggested that pooling the efficacy results for bisphosphonates is appropriate [29]. We therefore used results of a meta-analysis of pooled data from the alendronate and risedronate studies conducted by ScHARR [15]. This study suggests that oral bisphosphonates resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 0.58 for vertebral fracture (95% CI, 0.51 to 0.67; seven RCTs; n = 9340), a RR of 0.71 for hip fracture (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.87; six RCTs; n = 19,233), an RR of 0.69 for wrist fracture (95% CI, 0.45 to 1.05; six RCTs; n = 1037), and a RR for other non-vertebral fractures of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.88; 11 RCTs; n = 22,372) that was used for other fractures in the model. These RRs were used for all oral bisphosphonates, including generics. After stopping medication, it was assumed a linear decrease of the effects for a duration similar to the duration of therapy, in line with previous economic analyses of oral bisphosphonates [30] and clinical data [31].

Medication persistence defined as a dichotomized variable (persistent or not) as to whether a patient continued therapy beyond an elapsed time period was included in the model, as previously done [32, 33]. Patients were at risk of discontinuation every 6 months within 3 years. For patients who stopped taking their therapy, the treatment cost immediately stopped and the offset-time period started at the same time. For those who discontinued therapy within 6 months, no treatment effect was received [32, 33], since at least 6 months of treatment is necessary to reduce the risk of fractures [34].

Persistence data up to 3 years was extracted from the NostraData pharmacy panel of over 3500 stores, representing 65–70% of all dispensed scripts in Australia. The oral bisphosphonate usage of patients who initiated to the market between January 2012 and December 2015 was extracted for this analysis, and a permissible gap of 180 days was selected. In total, data from 165,017 patients were analyzed. Patients who switched from their therapy to a non-bisphosphonate therapy (e.g., denosumab) were identified and excluded from the persistency analysis, leaving a total of 151,422 patients within the final analysis. This cohort of patients was then tracked from January 2012 through April 2017. Persistence data for risedronate were conservatively also used for generic risedronate, even if persistence has been shown to be lower for generic drugs [35]. The probability of persistence with GR risedronate, risedronate, and weekly alendronate over time is shown in Fig. 1. At 1 year, more patients were persistent with GR risedronate (39%) compared to weekly alendronate (33%) and weekly risedronate (24%). At the end of the 3-year period, respectively, 12%, 9%, and 5% were persistent with GR risedronate, weekly alendronate, and weekly risedronate.

Fig. 1.

Persistence rates to oral bisphosphonates up to 3 years

Treatment cost includes drug costs and monitoring. The drug prices were derived from Ameli on 26 February 2018 [16] (see Table 1). We also assigned the cost of one general physician visit every 6 months of treatment (for persistent patients) and the cost of one bone density measurement at year 1. Adverse events observed with oral bisphosphates are generally mild and transient. The cost and quality of life impact of adverse events would thus only be minor and not affect the results and were therefore not included in the analysis.

Analyses

A total of 1,000,000 of trials were run for each analysis. Total costs, disaggregated costs (i.e., treatment costs that include drug costs adjusted by persistence and monitoring costs, and fracture-related costs), and accumulated QALYs were estimated for each treatment. If GR risedronate is associated with more QALYs and less costs than an alternative, it is considered dominant or cost-saving (when compared to no treatment). If GR risedronate provides more QALYs and more costs, then we computed the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) defined as the difference between GR risedronate and the comparator treatment in terms of total costs (expressed in €2017) divided by the difference between them in terms of QALYs. The ICER represents then the additional cost per QALY gained of GR risedronate. If the ICER is above a certain threshold, then the cost is too high for the benefits and the intervention is not considered as cost-effective. In France, no specific threshold is actually used for defining cost-effectiveness. The World Health Organization has suggested a value of three times the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as the QALY value to be used as cost-effectiveness threshold in developed countries. Borgström et al. [36] have suggested a threshold for QALY equal to two times the GDP per capita for industrialized countries (+ − €86,000 in France). This assumption has been used for defining fracture risk thresholds in several countries [37, 38].

Sensitivity analyses were then systematically performed to assess the impact of model parameters on the results. One-way sensitivity analyses assessed the impact of single parameters on the results and were conducted on discount rates, fracture costs, fracture risks, fracture disutility, mortality, and treatment costs. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted on medication persistence varying by ± 25% and ± 50% the incremental difference in persistence between GR risedronate and each active comparator. We also conducted one sensitivity analysis where treatment-specific efficacy data (alendronate and risedronate) were used, derived from the NICE appraisal [15]. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were also undertaken to examine the effect of the joint uncertainty surrounding the model variables. Nearly all parameters were varying simultaneously over plausible range of values. To perform this probabilistic analysis, a specific distribution was attributed to each parameter around the point estimate used in the base-case analysis, including for medication persistence. We followed guideline [39] for the selection of distributions and used 95% confidence intervals when available. A report including all distributions and values is available at the corresponding author per request.

Results

Base-case analysis

Table 2 presents the total and disaggregated healthcare costs, accumulated QALYs, the incremental costs and QALY, and the ICER (expressed in cost per QALY gained) of GR risedronate compared with generic risedronate, alendronate, and no treatment. In women aged 70 years with BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures, GR risedronate is associated with a €153 higher treatment cost compared to generic risedronate, but leads to a €132 reduction in fracture costs resulting from the improved persistence. The incremental total healthcare cost of GR risedronate was thus estimated at + €21 (€153–€132), while GR risedronate is associated with 0.090 additional QALY gained. The cost per QALY gained of GR risedronate was thus estimated at €2341 (= €21/0.090) per QALY gained compared to generic risedronate and at €2037 compared to alendronate.

Table 2.

Lifetime healthcare costs, QALYs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (cost (€) per QALY gained) of GR risedronate compared with generic risedronate, alendronate, and no treatment at the age of 70 years

| GR risedronate | Generic risedronate | Alendronate | No treatment | Incremental | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vs generic risedronate | Vs alendronate | Vs no treatment | |||||

| BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures | |||||||

| Treatment cost | 343 | 191 | 298 | 0 | 153 | 45 | 343 |

| Fractures-related cost | 27,051 | 27,182 | 27,091 | 27,418 | − 132 | − 40 | − 367 |

| Total healthcare cost | 27,394 | 27,373 | 27,390 | 27,418 | 21 | 5 | − 24 |

| QALY | 9.4902 | 9.4812 | 9.4881 | 9.4664 | 0.0090 | 0.0021 | 0.0238 |

| ICER (€ per QALY gained) | 2341 | 2037 | Cost-saving* | ||||

| BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 | |||||||

| Treatment cost | 343 | 191 | 298 | 0 | 152 | 45 | 343 |

| Fractures-related cost | 16,706 | 16,743 | 16,728 | 16,898 | − 37 | − 22 | − 192 |

| Total healthcare cost | 17,050 | 16,933 | 17,026 | 16,898 | 117 | 24 | 152 |

| QALY | 10.0674 | 10.0621 | 10.0655 | 10.0564 | 0.0053 | 0.0019 | 0.011 |

| ICER (€ per QALY gained) | 21,875 | 12,548 | 13,707 | ||||

| Prevalent vertebral fractures | |||||||

| Treatment cost | 343 | 191 | 298 | 0 | 152 | 45 | 343 |

| Fractures-related cost | 15,878 | 15,929 | 15,899 | 16,029 | − 51 | − 21 | − 151 |

| Total healthcare cost | 16,221 | 16,119 | 16,198 | 16,029 | 102 | 23 | 192 |

| QALY | 9.8881 | 9.8830 | 9.8868 | 9.8736 | 0.0051 | 0.0013 | 0.0145 |

| ICER (€ per QALY gained) | 19,922 | 18,259 | 13,311 | ||||

GR, gastro-resistant; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year

*Additional treatment costs lower than fractures-related cost saved with more prevented fractures

Compared to no treatment, the treatment costs of GR risedronate (€343) was lower than the saved costs (€367) resulting from the prevention of additional fractures induced by the improved persistence. GR risedronate is thus cost-saving compared to no treatment. From the age of 75 years, GR risedronate is dominant (more QALY for less total costs) compared to both generic risedronate and alendronate.

Additional scenarios

In women aged 70 years with BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 or prevalent vertebral fractures only, the cost per QALY gained of GR risedronate falls below €25,000 for all comparators (Table 2). Additional scenarios on the age range 60–80 years were conducted (Table 3). GR risedronate was dominant/cost-saving compared to all comparators in all women aged 80 years and over. In all of the simulated populations, GR risedronate was cost-effective compared to generic risedronate, alendronate, and no treatment at a threshold of €60,000 per QALY gained.

Table 3.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (cost (€) per QALY gained) of GR risedronate compared with generic risedronate, alendronate, and no treatment for women aged 60–80 years

| GR risedronate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vs generic risedronate | Vs alendronate | Vs no treatment | |

| BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures | |||

| 60 years | 18,295 | 16,468 | 12,545 |

| 65 years | 8067 | 11,985 | 3443 |

| 70 years | 2341 | 2037 | Cost-saving* |

| 75 years | Dominant** | Dominant | Cost-saving |

| 80 years | Dominant | Dominant | Cost-saving |

| BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 | |||

| 60 years | 55,409 | 32,790 | 40,117 |

| 65 years | 33,664 | 27,457 | 22,295 |

| 70 years | 21,875 | 12,548 | 13,707 |

| 75 years | Dominant | 9811 | Cost-saving |

| 80 years | Dominant | Dominant | Cost-saving |

| Prevalent vertebral fractures | |||

| 60 years | 46,641 | 43,913 | 34,963 |

| 65 years | 33,664 | 27,457 | 22,295 |

| 70 years | 19,922 | 18,259 | 13,311 |

| 75 years | 1682 | 9585 | Cost-saving |

| 80 years | Dominant | Dominant | Cost-saving |

*Additional treatment costs lower than fractures-related cost saved with more prevented fractures

**Lower costs for more QALYs

Sensitivity analyses

Table 4 reports the results of the one-way sensitivity analyses in women aged 70 years with BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures. The ICERs of GR risedronate were shown to be markedly affected by the incremental difference in persistence between GR risedronate and the active comparator treatment. Other analyses further suggested that the ICERs of GR risedronate were shown to moderately increase when decreasing fracture costs or fracture disutilities, when using discount rates of 5% and when treatment cost is increasing. In all these sensitivity analyses, the ICERs of GR risedronate remain below €10,000 for all comparators, except when using treatment-specific efficacy data where GR risedronate was dominated (more costs, less QALYs) by weekly alendronate.

Table 4.

One-way sensitivity analyses on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of GR risedronate compared to generic risedronate, alendronate, and no treatment in women aged 70 years with BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures

| GR risedronate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vs generic risedronate | Vs alendronate | Vs no treatment | |

| Base-case | 2341 | 2037 | Cost-saving |

| Fracture costs 25% lower | 5564 | 8038 | 4484 |

| Fracture costs 25% higher | Dominant | Dominant | Cost-saving |

| Fracture disutilities 25% higher | 391 | 3624 | Cost-saving |

| Fracture disutilities 25% lower | 2481 | 8860 | 912 |

| Discount rates 5% | 7453 | 7921 | 937 |

| Excess mortality (50%) | 2953 | 1279 | 446 |

| GR risedronate cost + 10% | 6164 | 17,978 | 425 |

| GR risedronate cost − 10% | Dominant | Dominant | Cost-saving |

| Treatment-specific efficacy data | 5141 | Dominated | 2071 |

| Incremental persistence + 50% | 481 | 1272 | – |

| Incremental persistence + 25% | 738 | 1398 | – |

| Incremental persistence − 25% | 6270 | 4349 | – |

| Incremental persistence − 50% | 13,802 | 9494 | – |

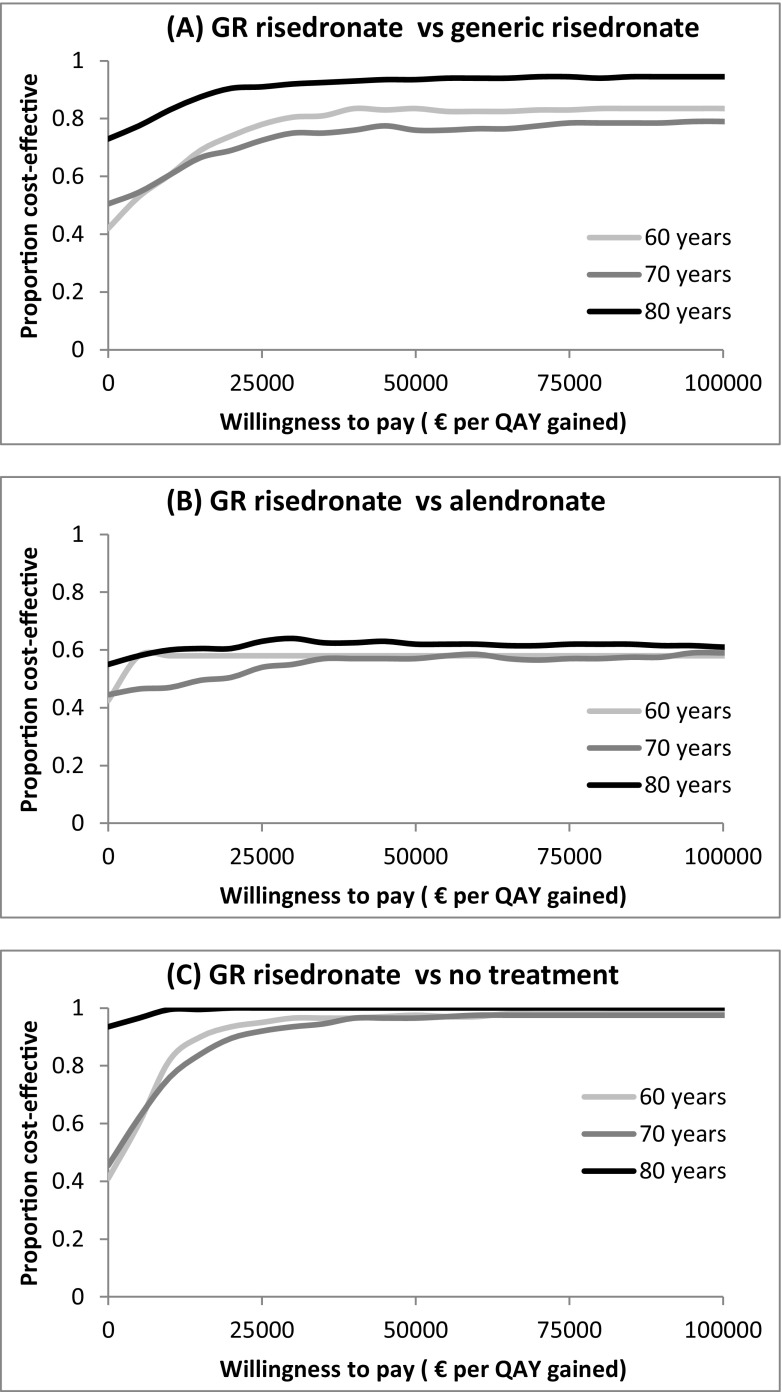

The results of the probabilistic sensitivity analyses are provided in Fig. 2 where the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves show the probability that GR risedronate is cost-effective compared to the other comparator for different willingness to pay of decision makers per QALY gained. The curves suggest that GR risedronate was cost-effective in at least 50% of the simulations for thresholds up to €100,000 per QALY gained. At a threshold of €85,000 per QALY gained (= 2 × GDP in France), in women aged 70 years, GR risedronate was cost-effective in 98%, 79%, and 58% compared to no treatment, generic risedronate, and alendronate, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves of GR risedronate versus generic risedronate (a), alendronate (b), and no treatment (c) in women aged 60, 70, and 80 years with prevalent vertebral fractures and a BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5

Discussion

This study suggests that GR risedronate is cost-effective compared with weekly alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment in France. In all of the simulated populations, the ICERs of GR risedronate were below €60,000 per QALY gained and GR risedronate could thus be considered as a cost-effective option. The cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate improved with increasing patient age and fracture risk at baseline, as the benefits of improved persistence become higher when increasing the fracture risk of the population. So, in women with a BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and prevalent vertebral fractures, the cost per QALY gained of GR risedronate compared to alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment was always below €20,000 per QALY gained. In women aged 75 years and older, GR risedronate was even shown to be dominant (more QALYs, less costs) compared to generic risedronate and alendronate, and cost-saving (more QALYs, lower total costs than no treatment) in women aged 70 years and over. Sensitivity analyses suggest that results are most sensitive to the incremental difference in persistence between GR risedronate and the active comparators.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first results about the cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Previous studies have already shown that risedronate is cost-effective compared to no treatment [28, 40]. Our study further confirms the importance of medication persistence in pharmacoeconomic analysis in osteoporosis [41], suggesting that a more expensive drug with improved persistence has the potential to be cost-effective. One strength of our study is the use of a large longitudinal database to assess persistence to all medications. Persistence data were however derived from an Australian study since GR risedronate was not yet used in France. In another Canadian study including a sample of 48,631 patients that initiated an oral bisphosphonate for the first time from July 2012 to November 2013 [42], higher adherence defined as the percentage of patients retained after 12 months following initiation was also observed for GR risedronate compared to weekly alendronate and risedronate. We could thus expect similar higher persistence with GR risedronate in France, although it would be important in the future to collect persistence data to GR risedronate in France to confirm our results.

There are some additional potential limitations to this study. First, although the results were robust over all scenarios and sensitivity analyses, GR risedronate was dominated by weekly alendronate when including treatment-specific efficacy data for alendronate and risedronate. There is however no evidence of a difference in effect on fractures between bisphosphonates [28], and the NICE has suggested that pooling the efficacy results for bisphosphonates is appropriate [29] in line with our base-case assumption. Second, our analyses were conducted in women with BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 and/or prevalent vertebral fractures in line with current reimbursement criteria for osteoporotic treatment in France. Further assessment of the cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate in other populations (e.g., based on FRAX score or in patients with an imminent risk fracture) could be interesting. Third, only persistence data were available and used in this analysis. We did not model the fact that patients could not take adequately all prescribed drugs (defined as medication adherence). Fourth, this analysis was limited to the most relevant comparators from the same therapeutic class (i.e., the traditional oral bisphosphonates: weekly alendronate and generic risedronate) for which persistence data were available in the persistence database. Other treatments such as denosumab or yearly intravenous are also available to treat osteoporosis. It would be interesting in the future to investigate the cost-effectiveness of GR risedronate compared to other drugs although this comparison could be more uncertain given the absence of direct comparison of efficacy between drugs.

Other potential limitations are related to the model and data. The most important are availability of data. Although data used to construct the model were based on French literature whenever possible, some data were derived from other countries. In particular, the effects of fracture on utility were not derived from a French study. However, we used an international multinational study (ICUROS), the largest study worldwide assessing the effects of fractures on quality of life. Previous economic analyses have already been conducted in France using this model [18, 43].

In conclusion, this study provides the first economic results about GR risedronate, suggesting that GR risedronate is a cost-effective strategy compared with alendronate, generic risedronate, and no treatment for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in France. As our results were most sensitive to the incremental difference in persistence between active drugs, it would be important to confirm the improved persistence associated with GR risedronate in other studies. GR risedronate may therefore represent a convenient and cost-effective dosing regimen for oral bisphosphonate therapy to treat osteoporosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Prince Mutaib Chair for Biomarkers of Osteoporosis, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for its support.

Funding information

This work was funded by Teva and Theramex.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

MH has received research grant through institution from Amgen, Radius Health, and Teva and lecture fees from Radius. JYR has received consulting fees or paid advisory boards from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Radius Health, Pierre Fabre, Teva; lecture fees when speaking at the invitation of sponsor: IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, Dairy Research Council, Teva; and grant support from industry (all through institution) from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, Radius Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C, Delmas PD, Reginster JY, Borgstrom F, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(4):399–428. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0560-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1453–1460. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiligsmann M, Rabenda V, Gathon HJ, Ethgen O, Reginster JY. Potential clinical and economic impact of nonadherence with osteoporosis medications. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;86(3):202–210. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClung MR, Miller PD, Brown JP, Zanchetta J, Bolognese MA, Benhamou CL, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel delayed-release risedronate 35 mg once-a-week tablet. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):267–276. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1791-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClung MR, Balske A, Burgio DE, Wenderoth D, Recker RR. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with delayed-release risedronate 35 mg weekly for 2 years. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):301–310. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiligsmann M, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, Flamion B, Bergmann P, Body JJ, Boonen S, Bruyere O, Devogelaer JP, Goemaere S, Kaufman JM, Rozenberg S, Reginster JY. Health technology assessment in osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiligsmann M, Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Gathon HJ, Reginster JY. Development and validation of a Markov microsimulation model for the economic evaluation of treatments in osteoporosis. Value Health. 2009;12(5):687–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E, CHEERS Task Force Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health. 2013;16(2):e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, et al. Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:137. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briot K, Maravic M, Roux C. Changes in number and incidence of hip fractures over 12 years in France. Bone. 2015;81:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouee S, Lafuma A, Fagnani F, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY. Estimation of direct unit costs associated with non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures in five European countries. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26(12):1063–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotte FE, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prigent A, Auraaen A, Kamendje-Tchokobou B, Durand-Zaleski I, Chevreul K. Health-related quality of life and utility scores in people with mental disorders: a comparison with the non-mentally ill general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):2804–2817. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110302804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svedbom A, Borgstom F, Hernlund E, Strom O, Alekna V, Bianchi ML, et al. Quality of life for up to 18 months after low-energy hip, vertebral, and distal forearm fractures-results from the ICUROS. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(3):557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Clinical Excellence and Health (2008) Raloxifene for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women. Technology appraisal guidance [TA160]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta160/chapter/4-evidence-and-interpretation#clinical-effectiveness. Access 15 Jun 2017

- 16.https://www.ameli.fr/etablissement-de-sante/exercice-professionnel/nomenclatures-codage/medicaments. Access 28 Feb 2018

- 17.Hiligsmann M, Reginster JY. Cost effectiveness of denosumab compared with oral bisphosphonates in the treatment of post-menopausal osteoporotic women in Belgium. PharmacoEconomics. 2011;29(10):895–911. doi: 10.2165/11539980-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiligsmann M, Burlet N, Fardellone P, Al-Daghri N, Reginster JY. Public health impact and economic evaluation of vitamin D-fortified dairy products for fracture prevention in France. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(3):833–840. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3786-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P, et al. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35(2):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A. Risk of hip fracture according to the World Health Organization criteria for osteopenia and osteoporosis. Bone. 2000;27(5):585–590. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.INSEE. Mortality table 2013–2015. Available from https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2851503?sommaire=2851587. Access 15 Jun 2017

- 22.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Excess mortality after hospitalisation for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(2):108–112. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK. The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone. 2003;32(5):468–473. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drame M, Fierobe F, Lang PO, Jolly D, Boyer F, Mahmoudi R, et al. Predictors of institution admission in the year following acute hospitalisation of elderly people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(5):399–403. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DGCS, CNSA, ATIH - enquête de coûts 2013 en établissements d’hébergement pour personnes âgées dépendantes (EHPAD), May 2015. Available from https://www.cnsa.fr/documentation/plaquette_resultats_enquete_couts2013_vdef.pdf. Access 15 Jun 2017

- 26.Weaver J, Sajjan S, Lewiecki EM, Harris ST, Marvos P. Prevalence and Cost of subsequent fractures among U.S. patients with an incident fracture. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):461–471. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiligsmann M, Ethgen O, Richy F, Reginster JY. Utility values associated with osteoporotic fracture: a systematic review of the literature. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82(4):288–292. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis S, Martyn-St James M, Sanderson J, Stevens J, Goka E, Rawdin A, Sadler S, Wong R, Campbell F, Stevenson M, Strong M, Selby P, Gittoes N. A systematic review and economic evaluation of bisphosphonates for the prevention of fragility fractures. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(78):1–406. doi: 10.3310/hta20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute for Clinical Excellence and Health (2017) Bisphosphonates for treating osteoporosis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA464]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta464/. Access 15 Jun 2017

- 30.Hiligsmann M, Evers SM, Ben Sedrine W, Kanis JA, Ramaekers B, Reginster JY, Silverman S, Wyers CE, Boonen A. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for postmenopausal osteoporosis. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(3):205–224. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strom O, Landfeldt E, Garellick G. Residual effect after oral bisphosphonate treatment and healthy adherer effects--the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA) Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(1):315–325. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2900-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiligsmann M, McGowan B, Bennett K, Barry M, Reginster JY. The clinical and economic burden of poor adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications in Ireland. Value Health. 2012;15(5):604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiligsmann M, Rabenda V, Bruyere O, Reginster JY. The clinical and economic burden of non-adherence with oral bisphosphonates in osteoporotic patients. Health Policy. 2010;96(2):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher AM, Rietbrock S, Olson M, van Staa TP. Fracture outcomes related to persistence and compliance with oral bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(10):1569–1575. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanis JA, Reginster JY, Kaufman JM, Ringe JD, Adachi JD, Hiligsmann M, Rizzoli R, Cooper C. A reappraisal of generic bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):213–221. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1796-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borgstrom F, Johnell O, Kanis JA, Jonsson B, Rehnberg C. At what hip fracture risk is it cost-effective to treat? International intervention thresholds for the treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(10):1459–1471. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lippuner K, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R. Cost-effective intervention thresholds against osteoporotic fractures based on FRAX(R) in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(11):2579–2589. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1869-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marques A, Lourenco O, Ortsater G, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, da Silva JA. Cost-effectiveness of intervention thresholds for the treatment of osteoporosis based on FRAX((R)) in Portugal. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016;99(2):131–141. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briggs A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borgstrom F, Strom O, Coelho J, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV, et al. The cost-effectiveness of risedronate in the UK for the management of osteoporosis using the FRAX. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(3):495–505. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiligsmann M, Boonen A, Rabenda V, Reginster JY. The importance of integrating medication adherence into pharmacoeconomic analyses: the example of osteoporosis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(2):159–166. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IMS Brogan (2013) Ontario public drug plan longitudinal database

- 43.Hiligsmann M, Reginster JY. The projected public health and economic impact of vitamin D fortified dairy products for fracture prevention in France. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(2):191–195. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2017.1375406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]