Abstract

Ginseng is one of the main representatives of traditional Chinese medicine and presents a wide range of pharmacological actions. Ginsenosides are the main class of active compounds found in ginseng. They demonstrate unique biological activity and medicinal value, namely anti-tumour, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, as well as anti-apoptotic properties. Increasing levels of stress in life are responsible for the increased incidence of nervous system diseases. Neurological diseases create a huge burden on the lives and health of individuals. In recent years, studies have indicated that ginsenosides play a pronounced positive role in the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases. Nevertheless, research is still at an early stage of development, and the complex mechanisms of action involved remain largely unknown. This review aimed to shed light into what is currently known about the mechanisms of action of ginsenosides in relation to Alzheimer's disease. Scientific material and theoretical bases for the treatment of nervous system diseases with purified Panax ginseng extracts are also discussed.

Keywords: ginseng, nervous system diseases, Alzheimer's disease, ginsenosides, β-amyloid level

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), which is the most common form of dementia, is a neurodegenerative disease that was first described by the German psychiatrist, Alois Alzheimer in 1907 (1). Despite great progress being made in the understanding of the pathogenesis of AD, no cure has yet been found. Three main neuropathological signs characterize AD: The loss of neurons, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (2). Amyloid plaques are predominantly composed of peptides, known as β-amyloid (Aβ), which are the main peptides to induce neuronal damage and apoptosis in patients with AD (3). NFTs are formed from the hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein (also known as τ protein) (4,5).

2. The history of ginseng as a drug

The ancient and rich experience of folk medicine in the countries of the Far East has paved the way for many valuable scientific medicines, and ginseng occupies a special place in this important group. The first information about this medicinal plant can be traced back into the distant past and is surrounded by an aura of legend and tradition. For dozens of centuries, ginseng has been the subject of worship for the peoples of the Far East and has played a significant role in the culture, commerce and even foreign policy of China and other East Asian states.

The first to discover the healing properties of ginseng, according to legend, is Lao Tzu (6th century BC), the founder of a religious and philosophical school in China. Ginseng has been known of for at least 4,000 years. The first mentions of it are found in the most ancient writings on medicinal plants, ‘Shen-nun’ and ‘Shen-Lun-ben-cao’, which date back to the 20th century BC. Numerous recommendations for the treatment of various diseases with ginseng are available in the new edition of the ‘E-lin’ medicine collection, compiled in China by Shi Bao-yuan in 2-1 BC. Ginseng is also described in several ancient Chinese sources from the 3rd century onwards (6,7).

Carl von Linné was the first to provide a systematic description of the genus and named it Panax L. (Linné, 1742; http://books.google.ru/books?id=30Y-AAAAcAAJ&dq=Genera+Plantarum&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=kI_cpWWP3×&sig=DbalIyFFHckeYxWqW-TegJC9iHs&hl=en&ei=07odS9_iE5HKsQPzotSECg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false). This title [from the Greek words ‘pan’ (meaning all) and ‘asos’ (meaning medicine)] reflects the idea of the all-healing properties of ginseng. Russian scientists have become increasingly interested in ginseng since the 19th century. The work of Kamensky (he studied Far Eastern ginseng for the first time) was followed by that of the Russian botanist and explorer, Carl Anton von Meyer (1841–1842) which deepened the knowledge of the taxonomy of the genus Panax and established the boundaries of the species, which are still accepted to this day. He described 5 types of ginseng and assigned the name of Panax Ginseng C.A.Meyer to true ginseng, and this name still holds to the present day (8,9; and Refs therein).

Reliable information on ginseng was provided by the writings of Far Eastern Russian researchers [Arsenyev (10), Przhevalsky (11), Maak (12), Maksimovich (13) and Komarov (14)]. In 1868, Y.K. Trapp (https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Трапп,_Юлий_Карлович) included ginseng in his pharmacognosy guide.

Relevant studies on the biology and culture of ginseng [Shishkin (15), Gutnikova (16,17), Vysotsky (18), Bayanova (19) and Kurentsova (20)], have been carried out in the Far East of the former USSR since 1930. Several pharmacological [Zakutinsky (21), Burkat and Saksonov (22) and Kiselev (23)] and clinical works [Shapiro (24), Kuzminskaya (25) and Buturlin (26)] have been published since then. The Far Eastern academician scientists, Elyakov (founder of the Institute of the Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences) and Brekhman provided significant contributions to the development of the science of Far Eastern medicinal plants, including ginseng (7,27).

The main active ingredients in ginseng are triterpene glycosides. These are ginsenosides, although they were more commonly known as panaxosides in the past. This was due to the fact that the pioneers of the study of ginseng saponins were domestic organic chemists under the guidance of the Academician of the Far East Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, G.B. Elyakov, who was the first to isolate 6 ginseng glycosides. The properties of an aglycone (a part of a glycoside that lacks a carbohydrate radical), led this group of scientists to term the glycosides of the protopanaxatriol group panaxosides, A, B and C, and the glycosides of the protopanaxadiol group panaxosides, D, E and F. Over time, other members of these groups were isolated; however, as there was no space left between C and D, the new opening compounds were termed ginsenosides and numbers that correspond to their mobility on chromatograms were assigned to them (7,28,29).

3. The chemical composition of Panax Ginseng C.A. Meyer

Saponins, which belong to the tetracyclic triterpene group, are among the biologically active substances (BAS) that are found in ginseng. Ginseng saponins are said to belong to the triterpenoid group of steroid origin (29).

Triterpene glycosides (ginsenosides) are considered the main active ingredients of ginseng, which were previously often termed panaxosides. The pioneers of the study of ginseng saponins are a group of Russian scientists led by the Academician Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, G.B. Elyakov. They were the first to isolate 6 glycosides of Panax ginseng in the 1960s (6,7). They termed the glycosides of the protopanaxatriol group, panaxosides A, B, and C, based on the properties of the aglycone, and the glycosides of the protopanaxadiol group, the panaxosides D, E and F. Over time, other members of these groups were identified; however, since there was no space between C and D, newly discovered compounds began to be termed ginsenosides and assigned numbers to them corresponding to their mobility shown on the chromatograms.

When clarifying the structure of an aglycone that ginseng glycosides, it was found to contain 3–6 monosaccharide residues (glucose, rhamnose, arabinose and xylose). Almost all glycosides have two carbohydrate chains bound to aglycone through typical glycosidic bonds.

The systematization of the literature data on the chemical composition of ginseng has led to data that are presented in Table I.

Table I.

List of most known active components (ginsenosides) of Panax Ginseng C.A. Meyer.

| No. | Chemical compounds | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20S-protopanaxadiol (3S,5R,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-17-[(2S)-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl]-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl- 2,3,5,6,7,9,11, 12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,12-diol С30H52O3 Мw = 460,743 g/mol |  |

| 2 | Panaxadiol (3S,5R,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-17-[(2R)-2,6,6-trimethyloxan-2-yl]-2,3,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclo-penta[a]phenanthrene-3,12-diol С30H52O3 Мw = 460,743 g/mol |  |

| 3 | Ginsenoside a1 (Panaxoside а1) (pseudoginsenoside F11) 2-[2-[[(3S,6S,8R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-3,12-dihydroxy-17-[(2S,5R)-5-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2-methyloxolan-2-yl]-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,7,9, 11,12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-6-yl]oxy]-4,5-dihydroxy- 6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl]oxy-6-methyloxane-3,4,5-triol С42H72O14 Мw = 801,024 g/mol |  |

| 4 | Ginsenoside а2 (Panaxoside а2) (Ginsenoside RG1) (2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[[(3S,5R,6S,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-3,12-dihydroxy-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-17-[(2S)-6-methyl-2-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxyhept-5-en-2-yl]-2,3,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-6-yl]oxy]-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol С42H72O14 Мw = 801,024 g/mol |  |

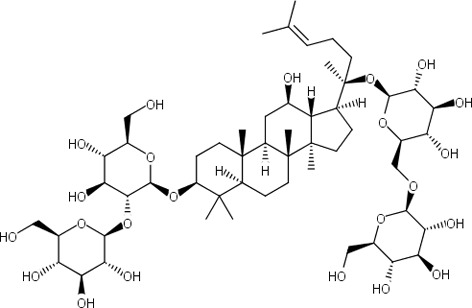

| 5 | Ginsenoside Rb1 (Panaxoside Rb1) 2-O-β-Glucopyranosyl-(3β,12β)-20-[(6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-12-hydroxydammar-24-en-3-yl β-D-glucopyranoside С54H92O23 Мw = 1109,307 g/mol |  |

| 6 | Ginsenoside Rb2 (Panaxoside Rb2) (3β,12β)-20-[(6-O-α-L-Arabinopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-12-hydroxydammar-24-en-3-yl 2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, NSC 308878 С53H90O22 Мw = 1079,281 g/mol |  |

| 7 | Ginsenoside Rb3 (Panaxoside Rb3) (3β,12β)-3-[(2-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxy]-12-hydroxydammar-24-en-20-yl6-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside С53H90O22 Мw =1079,281 g/mol |  |

| 8 | Ginsenoside Rg3 (Panaxoside Rg3) (2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-4,5-dihydroxy-2-[[(3S,5R,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-12-hydroxy-17-[(2S)-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept −5-en-2-yl]-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,7,9,11,12, 13,15,16,17-dodeca-hydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-yl]oxy]-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol С42H72O13 Мw =785,025 g/mol |  |

| 9 | Ginsenoside Rh2 (Panaxoside Rh2) (3β,12β)-12,20-Dihydroxydammar-24-en-3-yl-β-D-glucopyranoside, 20(S)-Ginsenoside-Rh2 С36H62O8 Мw = 622,884 g/mol |  |

| 10 | Ginsenoside Rh3 (Panaxoside Rh3) (3β, 12β,20Z)-12-Hydroxydammar-20(22), 24-dien-3-yl-β-D-glucopyranoside С36H60O7 Мw = 604,869 g/mol |  |

| 11 | Ginsenoside Rg2 (Panaxoside Rg2) (3β,6α,12β)-3,12,20-Trihydroxydammar-24-en-6-yl 2-O-(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside С42H72O13 Мw =785,025 g/mol |  |

| 12 | Ginsenoside Rg4 (Panaxoside Rg4) (2S,3R,4R,5R,6S)-2-[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[[(3S,5R,6S, 8R,9R, 10R,12R, 13R,14R,17S)-3, 12-dihydroxy-4,4,8,10, 14-pentamethyl-17-[(2Z)-6-methylhepta-2,5-dien-2-yl]-2, 3,5,6,7, 9,11,12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta [a]phenanthren-6-yl]oxy]-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl) oxan-3-yl] oxy-6-methyloxane-3, 4,5-triol С42H70O12 Мw =767,01 g/mol |  |

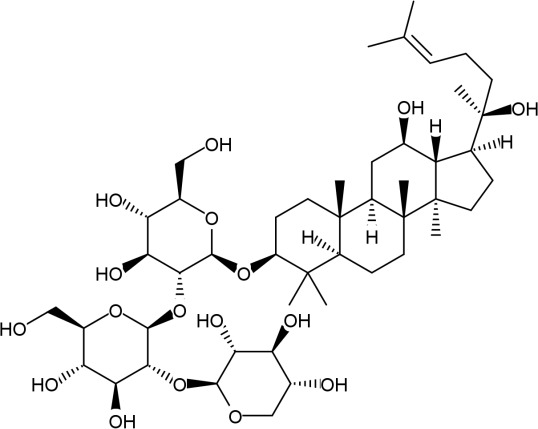

| 13 | Notoginsenoside R1 (Panaxoside R1) (2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2S)-2-[(3S,5R,6S,8R,9R,10R,12R, 13R, 14R,17S)-6-[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-3-[(2S,3R,4S,5R)-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxan-2-yl] oxyoxan-2-yl]oxy-3, 12-dihydroxy-4,4,8,10, 14-pentamethyl-2, 3,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,15,16, 17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl]-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol С47H80O18 Мw = 933,139 g/mol |  |

| 14 | Ginsenoside Re (Panaxoside Re) 3β,6α,12β)-20-(β-D-Glucopyranosyloxy)-3,12-dihydroxydammar-24-en-6-yl 2-O-(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, Chikusetsusaponin IVc, Ginsenoside B2, NSC 308877, Panaxoside Re С48H82O18 Мw = 947,166 g/mol |  |

| 15 | Ginsenoside Rh1 (Panaxoside Rh1) (2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[[(3S,5R,6S,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-3,12-dihydroxy-17-[(2S)-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl]-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-6-yl]oxy]-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol С36H62O9 Мw = 638,883 g/mol |  |

| 16 | Notoginsenoside ST4 (2S,3R,4S,5R)-2-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-4,5-dihydroxy-2-[[(3S,5R,8R,9R,10R,12R,13R,14R,17S)-12-hydroxy-17-[(2S)-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl]-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,15,16, 17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-yl]oxy]-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl]oxy-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl] oxyoxane-3,4,5-triol С47H80O17 Мw = 917,14 g/mol |  |

It is now established that the composition of the dry root is approximately as follows: Ginsenosides, 1–6%; carbohydrates (polysaccharides, trisaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, cellulose, pectins), 60–70%; nitrogen-containing compounds (amino acids, etc.), 12–16%; fat soluble components, 2%; vitamins, 0.05%; mineral substances 4–5% and moisture, 9–11% (28).

4. Ginsenosides and the acetylcholine level

Acetylcholine (ACh) is the main neurotransmitter in the parasympathetic nervous system and is rapidly destroyed by specific enzymes, known as cholinesterase, in the body. In addition to acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) can also destroy Ach (30). AChE and BChE play a significant role in AD. The inhibition of AChE and BChE provides additional benefits in the treatment of asthma. The cholinergic hypothesis, according to which the disease is caused by the reduced synthesis of ACh, was the first hypothesis to be proposed as the cause of AD. Indeed, the concentration of ACh in the brain during the first stages of AD is significantly below normal, and a decrease in the activity of cholinergic neurons is observed as a result (31). AChE inhibition-based therapy, which aims to increase the amount of Ach, is a method with which to alleviate AD in the initial and moderate stages (32). There are currently some doubts as to the cholinergic theory, as drugs that increase the level of ACh have a low efficiency. However, impelling methods of maintenance therapy have been created on this basis (33). Donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine are three AChE inhibitors that form the basis of maintenance therapy for individuals with asthma. The continuous use of these drugs can lead to side-effects, such as headaches, constipation, dizziness, nausea, vomiting and a loss of appetite, which severely affect the quality of life of patients (34).

AD presents with both increased AChE activation and the inhibition of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), which is the enzyme responsible for ACh biosynthesis (35).

Molecular docking and in vitro analyses have demonstrated that some of the ginsenosides that are obtained from ginseng root are AChE and BChE inhibitors. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Re, Rg1 and Rg3 have a significant inhibitory effect against AChE and BChE. The ginsenoside Re appears to provide the optimal AChE inhibitory activity from a series of ginsenosides (36).

The order of the inhibitory potential was as follows: Re>Rg3> Rg1>Rb1>Rb2>Rc for AChE, and Rg3>Rg1>Rb2>Rb1>Re>Rc for BChE. Ginsenoside Rc exhibited a weak inhibitory activity against AChE, while ginsenosides Rc and Re did so against BChE, compared with the positive controls (36).

Five new ginsenosides that are derivatives of ursolic acid have been isolated from Panax japonicus (37). All five were identified as AChE inhibitors in an evaluation of AChE activity in a PC12 cell model (rat adrenal pheochromocytoma) that was treated with Aβ25-35. However, it was found that their inhibitory potential was lower than that of donepezilum.

An extract from Panax quinquefolius (Cereboost™) was shown to exhibit AChE inhibitory activity in a mouse model of AD (male ICR mouse that received Aβ1-42 intracerebroventricular) (38). Cereboost™ increased the level of ACh in the brain by inhibiting AChE and reduced the level of Aβ1-42, while it improved the cognitive abilities of mice. In vitro, Cereboost™ increased ChAT expression and reduced the cytotoxicity of Aβ1-42. Identical results have been observed in other studies on mouse models of AD (ICR mice injected with scopolamine) (38). Ginsenoside Rg1 has been proven to be a more potent AChE inhibitor than Rb1 (40). Furthermore, ginsenoside Rg5 has been observed to dose-dependently inhibit AChE and activate ChAT in another model of AD (Wistar rats, which were injected with intracerebroventricular streptozocin). It also increased the ability of rats to learn and memorize the Morris water maze (MWM) (41).

It was also previously shown that an extract from a 4-year-old Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer root inhibited the neurotoxicity of Aβ. Choi et al examined the effect of dried white ginseng extract (WGE) on neuronal cell damage and memory impairment in mice injected with intrahippocampal AβO (10 µM). Mice were treated with WGE (100 and 500 mg/kg/day, p.o.) for 12 days after surgery. WGE improved memory impairment by inhibiting hippocampal cell death induced by AβO. In addition, the AβO-injected mice treated with WGE exhibited a restoration of reduced synaptophysin and ChAT intensity, and lower levels of ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 in the hippocampus compared with those of the vehicle-treated controls. These results suggest that WGE reverses memory impairment in AD by attenuating neuronal damage and neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of mice injected with AβO (42).

Some studies have shown that ginsenosides exert a neuroprotective effect by acting on neurotransmitters in AD. For example, ginsenosides can increase the levels of γ-aminobutyric acid, Ach and dopamine, and reduce the levels of glutamate and aspartic acid in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. In addition, ginsenosides can increase the level of glycine and serotonin in the blood (43). Apparently, ginseng contains substances that can increase the level of Ach in the brain of people with AD. Ginseng extracts can thus be used as palliative treatment in the early stages of AD.

5. Ginsenosides and the β-amyloid level

Aβ is the common name for several peptides that consist of 36–43 amino acid residues. The main species are the following: One peptide with 40 amino acid residues (Aβ1-40) and another of 42 amino acid residues (Aβ1-42) (44). Aβ is formed in the body from Aβ precursor protein (APP), which is a transmembrane protein that is concentrated in neurons through sequential proteolysis with beta secretase 1 (BACE1) and γ-secretase (45). Aβ forms insoluble Aβ filaments, which subsequently stick together in the intercellular space into dense formations known as senile plaques (46). There is also an alternative, non-amyloidogenic pathway, in which the first cleavage of APP is catalysed, not by BACE1, but by α-secretase and the result is soluble amyloid precursor protein α (sAPPα), which exerts anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective effects (47,48).

Some ginsenosides are BACE1 inhibitors as molecular docking and in vitro in studies have demonstrated. Their inhibitory ability decreases in a certain order: Rc>Rg1>Rb2>Rb1>Rg3>Re (36). Ginsenoside Re has not only been observed to reduce the activity of BACE1 and the expression of BACE1, but also to not affect the total levels of APP and sAPPα in a N2a/APP695 cell model (neuronal cells with an overexpression of APP) (49). It has also been shown that the decrease in BACE1 expression is associated with the activation of ginsenoside Re by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). Ginsenoside Rg1 is also a stimulator of PPARγ (50). The role of PPARγ in the pathogenesis of AD is not yet fully known.

Yan et al (51) demonstrated that ginsenoside Rd promoted the activation of the non-amyloidogenic pathway by activating estrogen receptor (ER). The methods they used in their study were as follows: 10 mg/kg ginsenoside Rd in ovariectomy/ovariectomized (OVX) + ginsenoside Rd group and an equivalent volume of saline in the sham-operated group and OVX group were administrated intraperitoneally for two months, respectively. The MWM was used to examine the cognitive function of rats, and the levels of sAPPα and Aβ in the hippocampi were measured. The culture medium of HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells was incubated with ginsenoside Rd, ER antagonist (ICI182.780), MAPK inhibitor (PD98059), or PI3K inhibitor (LY294002), respectively. The sAPPα levels were measured, and the expression levels of α-secretase, sAPPα, β-secretase, Aβ, phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), total AKT, p-ERK, total ERK, p-ERα, total ERα, p-ERβ and total Erβ were examined by western blot analysis to investigate the estrogenic-like activity of ginsenoside Rd.

Accordingly, ginsenoside Rd was also found to attenuate cognitive and memory impairment, increase the levels of sAPPα and to reduce extracellular Aβ in OVX rats. In HT22 cells, ginsenoside Rd upregulated the sAPPα levels, which were inhibited by the inhibitors of the MAPK and PI3K pathways. In addition, the inhibitor of ER prevented the ginsenoside Rd-induced release of sAPPα and the activation of the MAPK and PI3K pathways. Ginsenoside Rd increased the expression of α-secretase and sAPPα, while it decreased the expression of β-secretase and Aβ. Moreover, ginsenoside Rd promoted the phosphorylation of ERα at the Ser118 residue (51). Similar results have also been obtained for ginsenoside Rg1 (52,53).

It has been demonstrated that ginsenosides Rd and Rg1 not only significantly reduce the level of Aβ, but also increase the level of sAPPα, as it has been shown in animal models of AD (54).

Huang et al (55) aimed to investigate the effects of Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) on α-secretase and β-secretase involved in Aβ generation in SAMP8 mice. The results of their study revealed that PNS increased α-secretase activity perhaps by enhancing the level of ADAM9 expression, which itself was achieved by the upregulation of the expression of the ADAM9 gene. PNS significantly decreased the BACE1 protein level by downregulating the level of BACE1 gene expression and consequently precluded the activity of β-secretase (56).

That study indicated that PNS modulated the expression levels of proteins and genes associated with α- and β-secretase, thereby increasing α-secretase activity and reducing β-secretase activity, which may be one of the mechanisms of action of PNS precluding Aβ generation. Accordingly, PNS may be a promising agent for AD (55).

Endres and Fahrenholz (57) noted in their research that a disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain 10 (ADAM10) presents a worthwhile target with respect to the treatment of a neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD. Animal models with an overexpression of ADAM10 revealed a beneficial profile of the metalloproteinase with respect to learning and memory, plaque load and synaptogenesis. Initially, ADAM10 was suggested to be an enzyme, shaping the extracellular matrix by cleavage of collagen type IV, or to be a tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) convertase. In a relatively short period of time, a wide variety of additional substrates [with amyloid precursor protein (APP) probably being the most prominent]have been identified and the search is still ongoing. Hence, any side-effects concerning the therapeutic enhancement of ADAM10 α-secretase activity have to be considered (57).

However, in another stdy, the level of sAPPα was found to be higher in mice that were treated with ginsenoside Rh2 than in the control group. Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibited the endocytosis of APP and increased the distribution of APP on the cell membrane, thereby reducing the amyloid and increasing the non-amyloid pathway of cleaving APP (58). It has been proven that the level of cholesterol in neurons is involved in the pathogenesis of AD (59), and that the C-terminus of APP contains a cholesterol-binding domain (60).

Since it is known that the lipid raft is a specific cell membrane that is enriched with cholesterol, which plays an important role in the endocytosis of transmembrane proteins (61), and treatment with ginsenoside Rh2 significantly reduces the level of cholesterol in neurons, it has been concluded that the distribution of APP over the cell membrane is determined by the cholesterol in neurons (58). In addition to cholesterol, other lipids, such as phosphoinositides, are also involved in the pathogenesis of AD (62). One of the key phospholipids, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], is formed by phosphatidyl inositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) phosphorylation using a specific enzyme, phosphatidyl inositol-phosphate-4 kinase type 1γ. PI4P is formed via phosphatidylinositol by phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase 2α (PI4KIIα) (63). In vitro and in vivo, ginsenoside Rg3 has been observed to increase the levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 by activating PI4KIIα (64). PI(4,5)P2 contributes to the regulation of the mobility of transmembrane proteins in lipid rafts (65). In other words, PI(4,v5)P2 leads to changes in the fluidity and thickness of the membrane, and this, in turn, affects the activity of γ-secretase (66). Thus, high levels of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2, induced by ginsenoside Rg3, reduce the generation of Aβ by altering the activity of γ-secretase. The cognitive abilities of the animals in the MWM test following treatment with ginsenosides increased in all experiments, in relation to the control group with the AD model without treatment with ginsenosides (51–54,58).

Substances from ginseng extracts directly or indirectly affect the activity of secretases. However, such an approach to AD treatment appears to provide low-probability outcomes, as demonstrated by the fact that a number of large pharmaceutical companies have completed the clinical trials of various secretase inhibitors ahead of time: Verubecestat (67), lanabecestat (BACE1 inhibitors) (https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2018/update-on-phase-iii-clinical-trials-of-lanabecestat-for-alzheimers-disease-12062018.html) and semagacestat (γ-secretase inhibitor) (68). There was no improvement in patients who were taking the BACE1 inhibitors compared to the placebo group. The first and second phases of the clinical trials of semagacestat revealed a decrease in the plasma Aβ1-42 concentration at 3 h after administration. However, the concentration increased by 300% after 15 h, while there was no reduction in the cerebrospinal fluid. Although semagacestat reduced the number of amyloid plaques, the cognitive functions of the patients taking semagacestat worsened compared with the placebo group (67,68; http://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2018/update-on-phase-iii-clinical-trials-of-lanabecestat-for-alzheimers-disease-12062018.html).

It has been proven in vivo that ginsenoside Rg3 reduces the level of Aβ by increasing the activity and expression of neprilysin (69). Ginsenoside Rg1 has also been shown to increase the activity and expression of neprilysin (70). Neprilizin is one of the main enzymes that is capable of destroying Aβ.

It is known that protopanaxadiol (PPD)-type saponins are completely metabolized to 20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol (M1) by intestinal bacteria when taken orally; M1 and ginsenoside Rb1, as a representative of PPD-type saponins, were thus examined for cognitive disorders.

In a mouse model of AD induced by Aβ25-35 intracerebroventricular injection, impaired spatial memory was recovered by the p.o. administration of ginsenoside Rb1 or M1 (71). Although the expression levels of phosphorylated NF-H and synaptophysin were reduced in the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus of mice injected with Aβ25-35, their levels in the ginsenoside Rb1- and M1-treated mice were almost completely recovered to those of the control levels. The potencies of the effects did not differ between ginsenoside Rb1 and M1 when administered orally, suggesting that most of the ginsenoside Rb1 may be metabolized to M1, and M1 is an active principal of PPD-type saponins for memory improvement. M1 was shown to be effective in vitro and in vivo, indicating that ginseng drugs containing PPD-type saponins may reactivate neuronal function in AD by p.o. administration.

It has been demonstrated that AD is closely related to APP and presenilin-1 (PS1), which are overexpressed in AD (72). A study of UPLC/MS based metabolomics was conducted in order to better understand the mechanisms of action of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rg2, which counteract AD. The results revealed that ginsenosides Rg1 and Rg2 reduced rescue latency, compared to the AD model group, when cognitive function was tested in the MWM (71).

The impaired cognitive function and increased hippocampal Aβ deposition in mice with AD were ameliorated by ginsenoside Rg1 and Rg2. In addition, a total of 11 potential biomarkers that are associated with the metabolism of lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), hypoxanthine and sphingolipids were identified in the brains of mice with AD and their levels were partly restored following treatment with ginsenoside Rg1 and Rg2. Ginsenoside Rg1 and Rg2 treatment influenced the levels of hypoxanthine, dihydrosphingosine, hexadecasphinganine, LPC C 16:0, and LPC C 18:0 in mice with AD. Additionally, G-Rg1 treatment also influenced the levels of phytosphingosine, LPC C 13:0, LPC C 15:0, LPC C 18:1 and LPC C 18:3 in mice with AD (73).

A total of ten potential biomarkers were identified that were associated with the metabolism of lecithin, amino acids and sphingolipids in mice with AD. The peak intensities of LPC, tryptophan and dihydrosphingosine were lower, while those of phenylalanine were higher, in the mice with AD than in the control mice. Ginsenoside Rg1 treatment affected all three metabolic pathways, while ginsenoside Rb1 treatment affected lecithin and amino acid, but not sphingolipid metabolism. These data suggest that metabolomics has acquired a new method with which to discover the therapeutic benefits of ginsenosides in the treatment of AD (74).

Transgenic mice with AD have been used to study the protective properties of ginsenoside Rg1 on brain activity and synaptic plasticity, using conditional reflex fading and the western blotting technique. The results revealed that long-term memory improves following treatment with ginsenoside Rg1. Furthermore, ginsenoside Rg1 did not have a negative effect on normal diet and weight, while also inhibiting the levels of C-terminal fragments (CTF), phosphorylated τ-protein (p-Tau) and Aβ1-42 in mice with AD. Ginsenoside Rg1 was also able to improve the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) in the hippocampus. The results revealed that ginsenoside Rg1 exerted a neuroprotective effect via the activation of the BDNF-TrkB pathway and that weakened the expression of AD-associated proteins (75).

Furthermore, ginsenoside Rg1 has been found to increase the expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 1 (NR1) and N-methyl-2B D-aspartate (NR2B), while also attenuating the formation of NFTs, which directly affect the processes of learning and memory in mouse models with AD (76). It was discovered in recent studies that reproductive sex hormones, particularly oestrogen, play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. The rapid decline in oestrogen levels in postmenopausal women increases susceptibility to AD (77–79).

Thus, the absence of oestrogen can be a risk factor for AD. Zhang et al conducted a successful study to examine the neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on an OVX and D-galactose (D-gal)-injected rat model of AD (54). The results revealed that ginsenoside Rg1 not only restored impaired cognitive activity and positively affected spatial learning and memory, but also reduced the production of Aβ1-42 in the rats with AD. Seven weeks after surgery, ADAM10 expression in the hippocampus of the rats with AD was markedly decreased, while BACE1 expression increased compared with that in the sham-operated group (P<0.05). The levels of cleaved caspase-3 were increased in the hippocampus of rats with AD. Ginsenoside Rg1 and E2 treatment increased the ADAM10 level, while it reduced the BACE1 level and apoptosis. Moreover, moderate-dose i.e., 10 mg/kg/day and high-dose i.e., 20 mg/kg/day ginsenoside Rg1 exerted more poten effects than low-dose i.e., 5 mg/kg/day ginsenoside Rg1 (54). It is well known that chronic stress restrictions (in animals) can accelerate the process of AD generation and development. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects from oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inhibits the expression of NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), p47phox and RAC1 (80).

The association between ginsenoside Rg1 and the endoplasmic apoptotic pathway, as mediated by the reticulum, has also been examined in a rat model of AD. The results revealed that ginsenoside Rg1 reduced the accumulation of NFTs and the number of terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP filamentous ends that mark positive cells in mice with AD. More importantly, ginsenoside Rg1 inhibited the activation of apoptosis-associated phosphorylated-c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (p-JNK) and reduced the expression of glucose-regulated protein 78 (Grp78). Consequently, ginsenoside Rg1 exerted a neuroprotective effect by inhibiting the accumulation of NFTs and Aβ via inhibition of the ER stress-mediated pathway. The blocking of this pathway was triggered by the inositol-requiring enzyme-1 (IRE-1) and tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) pathway, as a result of the inhibition of the expression of p-JNK (81).

A scientific study found that pseudoginsenoside F11 (PF11), one of the components of ginseng, exerted a neuroprotective effect and enhanced the activity of neurons (82). Another study demonstrated that PF11 reduced the latency of rescue in the MWM and blocked the reduction of stepwise latency in the step test for Aβ11-42 and APP/PS1 mice. In addition, PF11 inhibited APP expression and the production of Aβ11-42 in the hippocampus and cortex of APP/PS1 mice. PF11 significantly increased the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase and reduced the amount of malondialdehyde (MDA). In addition, PF11 reduced the expression of JNK2, p53 and cleaved caspase-3. Thus, the improved recognition that is observed when subjects are exposed to ginsenoside PF11 may be associated with anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and inhibitory effects on amyloid genesis (83). By analogy, it has been found that ginsenoside R1 exerts a protective effect against Aβ-neurotoxicity (84).

In a previous study, ginsenoside Rb1 also reduced the presence of Aβ1-42 in the area of the cortex and hippocampus as well as improving the ability to learn in mice with AD (85). It is well known that cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), IkB-α and neuronal nitric oxide (NO) synthase (nNOS) are markers of neuroinflammation. Ginsenoside Rb1 reduced the number of COX-2-positive cells and positive IkB-α cells and increased the number of nNOS-positive cells in the hippocampus, as compared to the model group. The neuroprotective effect of ginsenoside Rb1 may thus be associated with anti-inflammatory markers in the hippocampus of mice with AD (85). More importantly, ginsenoside Rb1 has been observed to be more rapidly absorbed than ginsenoside Re and Rg1 (86). The effect of ginsenoside Rb1 may therefore be more potent than that of the other ginsenosides. In addition, ginsenoside Rb1 also demonstrated higher activity against neurotransmitters. For example, ginsenoside Rb1 has a higher absorbing activity against ONOO(−) than ginsenoside Rb2, Rc, Re, Rg1 and Rg3 (36).

Studies have shown that ginsenoside Rd can improve learning ability and memory, and can reduce neuronal death and loss in the CA1 region of the hippocampi of mice with AD. Moreover, ginsenoside Rd decreased the expression of ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Ibal), glial fibrillar acid protein (GFAP), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, caspase-3 and S100β mRNA. Ginsenoside Rd has also been observed to increase IL-10 and HSP70 mRNA expression levels (87). Furthermore, ginsenoside Rd has been shown to inhibit the expression of NF-κB p65, which is an important marker of the NF-κB pathway (88). These findings indicate that the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects of ginsenoside Rd are responsible for its neuroprotective effects.

AChE and BChE play a significant role in AD. The inhibition of AChE and BChE provides additional benefits to the treatment of AD. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Re, Rg1 and Rg3 have been shown to exert significant inhibitory effects against AChE and BChE. The Re compound of the series of ginsenosides inhibits the activity of AChE with optimal results (36). It has been demonstrated that ginsenosides exert neuroprotective effects via acting on neurotransmitters in AD. For example, ginsenosides can increase the levels of γ-aminobutyric acid, Ach and dopamine and reduce the levels of glutamate and aspartic acid in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. Moreover, ginsenosides can increase the level of glycine and serotonin in the blood (43). These studies provide a novel method for AD treatment.

Apart from ginsenosides, the glycolipoprotein fractions of ginseng extracts (gintonin) have also been the subject of an AD model study, which made five observations to indicate that gintonin counteracts the development of AD: Gintonin has been shown to promote the production of sAPPα by activating ADAM10, inhibit Aβ production in a dose-dependent manner, activate PI3K and AKT, and also not only to alleviate memory impairment caused by Aβ neurotoxicity, but also reduces the deposition of amyloid plaques in a mouse model of AD (89).

6. Ginsenosides and calcium ion levels in neurons

The mechanism of the neuronal damage that is caused by an increase in the intracellular level of calcium ions (Ca2+), which is in turn induced by glutamate, has been well studied (90). An increase in Ca2+ levels leads to the excessive stimulation of proteolytic enzymes, an increase in lipid peroxidation and an increase in the generation of ROS and nitrogen (91,92), thereby contributing to the excitotoxic process. Aβ not only causes the addition of new ion channels in the cell membrane, but also promotes the phosphorylation of existing calcium channels, thereby increasing the flow of calcium and initiating neurodegeneration (93). Aβ increases the phosphorylation of membrane-bound proteins and decreases the phosphorylation of cytosolic proteins, via MAPK, with the result that the intracellular level of Ca2+ increases (94). Ginsenoside Rg2 can significantly reduce the intracellular level of Ca2+ and ROS that is caused by Aβ25-35 in the PC12 cell model (95). In another study, ginsenoside Rg2 has been found to reduce not only the level of Ca2+, but also the lipid peroxidation that is caused by glutamate (96).

Notably, while ginsenoside Rb1 can reduce the intracellular level of Ca2+ when it was increased by administering Aβ25-35, the intracellular level of Ca2+ in healthy cells is not affected (97). Ginsenoside Rg1 has been observed to suppress the sensitivity of calcium channel activation to high values of membrane potential in an animal model of AD [Sprague Dawley (SD) rats administered Aβ25-35]. This effect disappears when ginsenoside Rg1 is used together with the MAPK inhibitor, PD98059 (98).

Quan et al (98) demonstrated that Rg1 treatment significantly reduced peak ICa, HVA densities, inhibited the sensitivity of channel activation to voltage, and enhanceed the sensitivity of channel inactivation to voltage; these effects of Rg1 were effectively inhibited by the MAPK inhibitor, PD98059. This indicated that Rg1 reduced Aβ-induced HVA calcium channel currents via MAPK in hippocampal neurons. The resulting reduced calcium influx may downregulate the level of calcium ions in the neurons and attenuate the neurotoxicity of Aβ. In summary, the data of that study demonstrated that Rg1 can reduce HVA calcium channel currents via MAPK in hippocampal neurons in Aβ-exposed brain slices (98).

As mentioned above, the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ is an important indicator of neurological disorders. Increased Ca2+ levels may increase the manifestation of epilepsy. Ginsenosides, in general and ginsenoside Rg3, in particular, can inhibit an increase in Ca2+ that is induced by Mg2+. Ginsenosides can modulate the disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis by inhibiting the glutamate ionotropic receptors that selectively bind N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA receptors) (99). In addition, oxidative stress can lead to hippocampal degeneration. It is noteworthy that ginsenosides reduce the oxidative stress that acts upon the parts of the nerve ending that correspond to the synapse (synaptosomes), and reduce the synaptic vesicles of dose-dependent presynaptic terminations. Moreover, it is not adenosine A1 receptors or adenosine A2B receptors, but adenosine A2A receptors that play an important role in the fight against epilepsy. Thus, ginsenosides exert an antiepileptic effect that they exert by activating the Adenosine-A2A receptors (100) (Table II).

Table II.

Pharmacological activity and mechanism of ginsenoside action on epilepsy, depression and reperfusion injury of the brain.

| Pharmacological intervention | Ginsenosides | Impact mechanism | Authors/(Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-epileptic effect | All ginsenosides | Activation of adenosine-A2A receptors | Shin et al (100) |

| Rg3 | Modulation of Ca2+ disrupted homeostasis via the inhibition of the nanomethylenediamine receptor | Doody et al (68) | |

| Anti-depressant effect | Rg1 | Increased levels of phosphorylation of protein kinase A and levels of phosphorylation of the cAMP-response elements of the activating protein. Expression of the hippocampal transmission pathway of the neurotrophic factor of the brain, hippocampal neurogenesis | Jiang et al (160), Liu et al (161) |

| All ginsenosides | Increased plasma ACTH levels and CORT blood levels | Wang et al (151), Kang et al (153) | |

| Rb1 | Activation 5-HT2A receptor | Yamada et al (152) | |

| Rb3 | Stops the process of reducing the mass of the hippocampus of the brain and the level of BDNF in the hippocampus | Cui et al (162) | |

| CK | Activation 5-HT2A receptor for the manifestation of the antidepressant effect, the regulation of levels of NA, ACTH and CORT in the brain. | Zhang et al (154), Yamada et al (152) | |

| Rg3 | Facilitation of the hippocampal-signalling pathway of BDNF, regulation of thelevels of NA, ACTH and CORT in the brain area. | Zhang et al (154), You et al (155) | |

| Protection against cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury | Rg1 | Decreases levels IL-1β, TNF-α and HMGB1, suppresses the expression of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-9. | Bao et al (126), Zhou et al (127) |

| Downregulation of proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) mRNA levels activated by protease | Yang et al (129), Xie et al (131), Sun et al (132), Huang et al (150) | ||

| Rb1 | Cancels the signalling pathway activation of NF-κB and the increase in TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the ischemic hemisphere. It prevents the reduction of thioredoxin-1 and superoxide dismutase and improves the expression of HSP70, Akt and the p-NF-κB p65 block when occluding the middle cerebral artery. | Huang et al (150) Zeng et al (149) | |

| Rd | Improves neuronal viability by inhibiting the overactive phosphorylation of NMDAR 2B and reducing levels of expression in the cell membrane | Liu et al (156), Xie et al (157) | |

| Re | Neuroprotective action by significantly reducing MDA and increasing the activity of H+-ATPhase | Chen et al (158) | |

| Rg3 | Reduces the expression of calpain I and caspase-3 mRNA in the CA1 region of the hippocampus | He et al (159) |

BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NA, noradrenaline; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CORT, corticosterone; HMGB1, high mobility protein group; PAR-1, protein and receptor-1 mRNA; NF, nuclear factor; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; NMDAR 2B, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor 2B; MDA, malondialdehyde; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor α.

An increase in the intracellular levels of Ca2+ mediates the activation of calcium-dependent enzymes, such as calpain (calcium-dependent non-lysosomal cysteine proteases). Calpain II is involved in the regulation of the apoptosis of certain cell types and performs this role by interacting with cysteine protease caspase-3, which has been identified as a key factor in apoptosis (101). The expression of calpain II and caspase-3 in vivo has been found to be reduced under the influence of ginsenoside Rg2 (96). The decrease in the activity of caspase-3 is caused by an increase in the B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2)/Bcl-2-associated X-protein (Bax) ratio, which is caused by ginsenoside Rg2 (95).

Caspase-3 is involved not only in the regulation of cell apoptosis, but also in the proteolytic cleavage of APP, with the formation of Aβ. The caspase-3-mediated proteolysis site is located in the cytoplasmic tail of APP, and cleavage at this site occurs in vivo in the hippocampal neurons following acute excitotoxic or cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury (102). An increased caspase-3 activity and expression have been observed in rat models of AD; however, the activity and expression of caspase-3 decreases markedly following treatment with ginsenosides Rg1 and Rd (81,87). The protein fraction, extracted from 4-year-old ginseng root, is also able to reduce the expression of caspase-3, as well as increase the Bcl-2/Bax ratio (103).

Other components of ginseng, apart from ginsenosides, are capable of influencing the intracellular level of Ca2+. Quercetin 3-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-β-D-galactopyranosyl (QXG) has been isolated from Panax notoginseng root. Of note, a previous study demonstrated that following the introduction of Aβ into cortical neurons and PC12 cells alone, the intracellular level of Ca2+ w not altered. However, following pre-treatment with QXG, the level of Ca2+ which was increased by Aβ was decreased by 50%. QXG also reduced the Aβ levels and caspase-3 activity in vivo (104).

7. Ginsenosides and neuroinflammatory processes

NF-κB is a transcription factor with various functions that is closely associated with the inflammatory response, the immune response and other pathological and physiological processes. NF-κB is in the cytoplasm in an inactive form in a normal state. When NF-κB is activated and enters the nucleus, it binds to target genes and induces transcription (105). NF-κB activates the transcription of TNF-α, various ILs (IL-1β and IL-6) and other target genes during inflammation, and contributes to the production of cytokines. It has also been found that NF-κB is associated with neurodegenerative diseases and is activated in the cerebral cortices of patients with AD (106). It has been shown, for ginsenoside Rb1 (107) and Rg5 (41) in vitro and for ginsenoside Rd (88) in vivo, that these ginsenosides are capable of reducing the expression of anti-inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α) and increasing the expression of IL-10 (for Rb1 and Rd) by suppressing the activation of NF-κB.

COX-2 is a key enzyme in the synthesis of prostaglandins and is an important mediator of inflammation (108). NO is a short-lived neurotransmitter that plays an important role in learning and memory mechanisms. As a result, impaired NO synthesis can lead to memory impairment and a decrease in learning ability (109). The fact that a number of inflammatory molecules can regulate the expression of NO synthases [NO synthase 1 (neuronal) (NOS1) and NO synthase 1 (inducible) (NOS2)] suggests that NOS should be considered a neuroinflammatory marker (110). The levels of COX-2 and NOS2 have been observed to increase significantly in models of AD (Wistar rats, administration of either Aβ or streptozocin), while the level of NOS1 decreases compared to the control group. However, treatment with ginsenoside Rg5 lowers the levels of COX-2 and NOS2 compared to the control values (41), and the level of COX-2 also decreases following treatment with ginsenoside Rb1, and the level of NOS1 increases (85).

Li et al examined the effect of ginsenoside Rg2 on neurotoxic activities induced by glutamate in PC12 cells (96). The results revealed that glutamate decreased cell viability, increased intracellular Ca2+ lipid peroxidation (the excessive production of MDA and NO) and the protein expression levels of calpain II, caspase-3 andAβ1-40 in PC12 cells. Ginsenoside Rg2 significantly attenuated the glutamate-induced neurotoxic effects upon these parameters at all doses tested. Their study suggested that ginsenoside Rg2 exerted a neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity through mechanisms related to anti-oxidation and anti-apoptosis. In addition, the inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg2 against the formation of Aβ1-40 suggested that ginsenoside Rg2 may also represent a potential treatment strategy for AD (96).

Li et al investigated and evaluated the neuroprotective effects of ginseng protein (GP) and its possible mechanisms of action in a cellular and animal model of AD. The results demonstrated that GP (10–100 µg/ml) significantly improved the survival rate of neurons and reduced cell apoptosis and the mRNA expression of caspase-3 and Bax/Bcl-2. In addition, GP (0.1 g/kg) significantly shortened the escape latency, prolonged the crossing times and the percentage of residence time; reduced the level of Aβ1-42 and p-Tau, the activity of t-NOS and iNOS, and the content of MDA and NO, improved the activity of SOD, the concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and the protein expression of p-PKA/PKA and cAMP response element binding protein (p-CREB/CREB) (103).

Ginseng extracts also exhibit antioxidant properties in AD models. In fact, ginsenoside Rg2 has been shown to decrease the concentration of MDA (a marker of lipid peroxidation) (96) and the level of ROS in vivo (95). The GP fraction activates SOD (antioxidant enzyme) and reduces the concentration of MDA in vitro (103). Furthermore, QXG prevents the formation of H2O2-induced ROS generation in a dose-dependent manner in vitro (104).

8. Ginsenosides and the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway

As mentioned above, ginseng root components are able to affect the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. The PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is one of the most important signalling pathways with which cells can avoid apoptosis and it plays a significant role in oxidative stress in AD. Kashour et al (110) examined the role of the late Simian virus 40 transcription factor (LSF), in anti-apoptotic APP pathways. The expression of wild-type human APP (hAPPwt) inhibited staurosporine (STS)-induced apoptosis and this inhibition was further enhanced by the expression of LSF. Thus, Kashour et al (111) established a connection between APP, LSF and AD. Akt (p-Akt) hyperphosphorylation regulates apoptotic factors, such as Bcl-2 and Bax, downstream signalling pathways, which allows for the regulation of apoptosis (112). The suppression of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway promotes cell apoptosis, while the activation of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway leads to the phosphorylation of the Akt cascade, which, in turn, protects the cells from oxidative stress (113).

Cui et al examined the protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 on Aβ25-35-induced neurotoxicity to PC12 cells and identified a potential molecular signalling pathway involved. Ginsenoside Rg2 attenuated the cleavage of caspase-3 induced by Aβ25-35 thereby improving cell survival and significantly enhanced the phosphorylation of Akt in PC12 cells. Additionally, pre-treatment with PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, completely abolished the protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 against Aβ25-35-induced neuronal cell apoptosis. These findings unambiguously suggested that the protective effect of ginsenoside Rg2 against the Aβ25-35-induced apoptosis of PC12 cells was associated with activation of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway (95).

Li et al examined the therapeutic effect of GP on AD and its association with the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway in order to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of ginseng (114). It was found that the cognitive abilities of the rats with AD were increased and the level of Aβ was also reduced by treatment with GP. GP also reduced the content of Aβ1-42 and p-Tau, and increased the mRNA and protein expression of PI3K, p-Akt/Akt and Bcl-2/Bax in the hippocampus (114).

9. Ginsenosides and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles

As mentioned above, AD is characterized by the accumulation of NFTs in cerebral tissue. NFTs are mainly composed of hyper p-Tau. τ-protein is a microtubule-related protein that is expressed in the central nervous system. It induces microtubule assembly and stabilisation. However, excessive p-Tau forms NFTs and leads to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal degeneration and cognitive impairment (115). In addition, abnormal hyperphosphorylation renders the τ-protein resistant to proteolytic degradation, which leads to the gradual accumulation of p-Tau in the cell and promotes the formation of NFTs. The inhibition of p-Tau can therefore be a potential therapeutic strategy for the prevention of AD.

Okadaic acid (OKA), a potent phosphatase inhibitor, often used to mimic the symptom of AD damaged by NFTs, was used in the study by Song et al to examine the effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on memory improvement and related mechanisms in SD rats. According to their study, it can be concluded that ginsenoside Rg1 protects rats from OKA-induced neurotoxicity. The possible neuroprotective mechanisms may be that Rg1 decreases OKA-induced memory impairment through the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3)β/Tau signalling pathway and/or by attenuating Aβ formation. Thus, their study indicates that ginsenoside Rg1 may be a potential prophylactic drug for AD (116).

Plattner et al noted in their study that the hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein Tau is a characteristic feature of neurodegenerative tauopathies, including AD (117). The overactivation of proline-directed kinases, such as cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)5 and GSK3, has been implicated in the aberrant phosphorylation of Tau at proline-directed sites. The results obtained in the study by Plattner et al prove the role of GSK3 as a key mediator of Tau hyperphosphorylation, whereas Cdk5 acts as a modulator of Tau hyperphosphorylation via the inhibitory regulation of GSK3 (117).

Li et al (118) сonvincingly proved in their study that pre-treatment of adult male SD rats with ginsenoside Rd (10 mg/kg for 7 days) or that of cultured cortical neurons (2.5 or 5 mol/l for 12 h) reduced OKA-induced neurotoxicity and Tau hyperphosphorylation by enhancing the activities of protein phosphatase 2A. The results of their study implied that ginsenoside Rd protected the SD rats and cultured cortical neurons against OA-induced toxicity (118).

Zhang et al (119) subjected SD rats to focal cerebral ischemia. Treatment with ginsenoside Rd attenuated the ischemia-induced enhancement of Tau phosphorylation and ameliorated behavioral impairment. Furthermore, they revealed that ginsenoside Rd inhibited the activity of GSK-3β, the most important kinase involved in Tau phosphorylation, but enhanced the activity of PKB/Akt, a key kinase suppressing GSK-3β activity (119).

A decrease in the activity of protein phosphatase 2A (PP-2A) in the cerebrum of individuals with AD is another cause of τ-protein hyperphosphorylation. PP-2A is the key serine/threonine phosphatase and presents broad substrate specificity. It is involved in the dephosphorylation of the τ-protein (120). It has been proven that ginsenoside Rd is capable of activating PP-2A in vitro and in vivo, and thereby reducing the level of p-Tau (121).

It has also been demonstrated that various ginsenosides can reduce the level of p-Tau and prevent the formation of p-Tau (43). However, to date, there is no clear understanding of the mechanisms through which this occurs.

Ginsenoside Rg1 has been observed to reduce the formation of NFTs in a study on transgenic rats that have increased APP and Aβ production. The authors of that study associated the accumulation of NFTs with brain-cell apoptosis (81). Furthermore, it was shown that ginsenoside Rg1 blocked the stress-apoptotic pathway that was caused by the disruption of the endoplasmic reticulum. The blocking of this pathway was initiated by the inhibition of the expression of IRE-1, factor 2, which is associated with TRAF2 and p-JNK. Moreover, as mentioned above, ginsenoside Rg1 inhibited apoptosis by increasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio (81,119).

In another study, it was assumed that the mechanism of NFTs accumulation was mediated by the influence of neprilysin and protein kinase A (PKA) on the phosphorylation of the τ-protein. Ginsenoside Rg1 reduced the activity and expression of PKA and increased the activity and expression of NEP at the same time, thereby inhibiting τ-protein hyperphosphorylation (70).

10. Ginsenosides and other factors

Elevated levels of Aβ can inhibit the expression of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). It has been found that BDNF is a synaptic-plasticity regulator that is involved in memory and cognitive functions. It plays a role in several events that constitute the pathological cascade in AD (122). A decrease in the level of IGF-1 in the brain is considered an important factor in the development of cognitive impairment and Aβ deposition (123). Ginsenoside Rg5 is able to increase the expression of BDNF and IGF-1, as shown in a study on a mouse model of AD. Ginsenoside Rg1 has not only been recorded to increase BDNF expression in a transgenic mouse model of AD, but also to activate TrkB, which acts as the BDNF receptor, thereby activating the BDNF/TrkB pathway (75). The effective transcription of BDNF only occurs following the activation of four transcription factors, including CREB (124). In most cases, CREB dysfunction plays a significant role in alterations in BDNF expression. The activation of CREB occurs mainly via phosphorylation at Ser133 by PKA, the activity of which is suppressed in the model of AD induced by Aβ. In fact, it has been shown that ginsenoside Rg1 increases the expression of BDNF via the phosphorylation of CREB and the activation of PKA (125).

Bone marrow stem cell (BMSC) transplantation is currently used in the treatment of cerebral ischemic disease. However, this method also presents some disadvantages, such as the low conversion rate of neural cells and weak proliferation ability (126). Ginsenoside Rg1 is a possible therapeutic agent for cerebral ischemia as its molecules are small enough to pass through the blood-brain barrier (127).

Reperfusion in cerebral ischemia can cause a significant disruption to the nervous system, and can increase the water content in the brain and the volume of infarction. Notably, ginsenoside Rg1 can improve nervous system deficiency, reduce cell apoptosis and increase the sensitivity of neuron-specific cell enolase and the gliofibrillary acidic protein of cells. Moreover, ginsenoside Rg1 not only significantly increases the protein level of Bcl-2, but also lowers the protein level of Bax (126).

The combined use of ginsenoside Rg1 and BMSC transplantation improves the quality of brain tissue by enhancing the neuro-like cell differentiation and the anti-apoptotic effect of ginsenoside Rg1 in reperfusion injury in cases of cerebral ischemia (126).

Ginsenoside Rg1 has also been found to improve neurological injury conditions by suppressing the expression of aquaporin 4 (127).

It is well known that the inflammation and apoptosis of neurons often occur with reperfusion injury following cerebral ischemia. Kashour et al clearly indicated in their study that the expression of dominant-negative late Simian virus 40 transcription factor (LSF) led to a marked increase in staurosporine-induced cell death that was significantly blocked by hAPPwt. These effects of Alzheimer's APP were accompanied by LSF nuclear translocation and dependent gene transcription. The activation of LSF is dependent on the expression of hAPPwt and is inhibited by the expression of dominant-negative forms of either phosphoinositide 3-kinase or Akt. These results demonstrate that LSF activation is required for the neuroprotective effects of APP via PI3K/Akt signalling (111).

Chem-oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is one of the downstream effectors of PPARγ. The PPARγ/HO-1 signalling system can inhibit apoptosis and inflammation. The association between ginsenoside Rg1 and the PPARγ/HO-1 signalling system in cerebral ischemic reperfusion injury has been investigated. Li et al (128) hypothesized that the neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 occur through PPARγ signaling in the ischemic brain. They demonstratyed that Rg1 markedly increased PPARγ expression in ischemic rats and in the cortical neurons of cerebral cortical neuron ischemic injury model rats. They also found that the selective PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, reduced PPARγ expression, suggesting that Rg1 may be a potent PPARγ agonist.

With the use of the middle cerebral artery occlusion rat model with cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury, Li et al (128) also observed that Rg1 effectively reduced neurological disorders and swelling of the brain in cerebral ischemic injury. These results are in accordance with those of other studies which demonstrated the effectiveness of Rg1 as a neuroprotector in various models of cerebral ischemic injury, including neurological deficits (129,130).

In addition, ginsenoside Rg1 has not only been found to reduce the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), but also to suppress the expression of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9 and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) in rat models (129). The infarct volume of the cerebrum and the permeability of the blood-brain barrier decreases with cerebral ischemic disease following exposure to ginsenoside Rg1. Ginsenoside Rg1 may attenuate neurological injury, the brain infarct volume and the blood-brain barrier permeability induced by focal cerebral ischemia in rats, and its neuroprotective mechanism is related to the downregulation of protease activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) expression. The permeability of the blood-brain barrier also increases with an increase in PAR-1 expression (131).

Moreover, astrocytes play an important role in the ischemic death of neurons. Although ginsenoside Rg1 does not alter the viability of astrocytes, its effect can weaken apoptosis and inhibit the intracellular overload of Ca2+ in astrocytes. In addition, ginsenoside Rg1 can reduce the loss of the transmembrane potential of the mitochondria and ROS production in astrocytes (132).

Metabolomic analyses have been performed in a number of studies, and substances whose level varied in the AD model have been identified and recovered under the action of various ginsenosides. In a previous study, a total of 10 potential biomarkers that were associated with the metabolism of lecithin, amino acids, and sphingolipids were identified in mice with AD based on metabolomics. These biomarkers in the plasma of mice with AD were disrupted. Following treatment with ginsenoside Re, the disrupted metabolic profiling was restored back to control-like levels, indicating that the protective effect of ginsenoside Re in AD was exerted through these pathways (133). In that study (133), the levels of hexadecasphinganine and phytosphingosine were both decreased in the plasma of mice with AD as compared to the control mice. Following treatment with ginsenoside Re, the levels of these two metabolites were significantly elevated. Thus, the results suggest that mice with AD have impaired sphingolipid metabolism, and therefore plasma sphingolipids can also be utilized as indicators of therapeutic response. The therapeutic effects of ginsenoside Re on mice with AD are exerted through the modulation of sphingolipid metabolic processes (133).

Ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 increase the concentrations of tryptophan, di-hydrosphingosine (Rg1 only), various lysosfatidylcholines (C22: 6, C20: 4, C18: 2, C16: 0, C18: 1 and C18: 0), and lower the levels of phenylalanine (53). Ginsenoside Rg2 increases the concentrations of hypoxanthine, dihydrosphingosine, hexadecasphinganine and lysosfatidylcholine C16: 0 and C18: 0 (73).

A comparative proteomics analysis was performed on a model of AD using the stable isotope labelling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) in order to examine the potential defence mechanisms of ginsenoside Rb1. Forty proteins were found that exhibited significant changes after the treatment of cells, into which Aβ had previously been introduced, with ginsenoside Rb1. As a result, the authors suggested that proteins, such as adenylyl cyclase associated protein 1, the isoform 2, the subunit β F-actin-closure protein and the subunit of the mitochondrial receptor TOM40, can act as potential biomarkers and regulatory proteins in protector mechanisms that prevent AD (134).

11. Ginsenosides and individuals with Alzheimer's disease

The American National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke, and the Alzheimer's Disease Association formed the most commonly used set of criteria for the diagnosis of AD. The following neuropsychological tests are therefore widely used to assess cognitive impairment: i) Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE); ii) AD assessment scale (ADAS), which includes the cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and the non-cognitive subscale (ADAS-non-cog); iii) ‘Frontal Assessment Battery’ (FAB) Test and iv) clinical dementia rating (CDR) (135).

Studies have been conducted to assess the effects of ginseng components on the course of AD in humans. The clinical efficacy of heat-processed ginseng with the novel ginsenoside complex, SG-135, was confirmed in relation to cognitive function in patients with moderately severe disease. An increase in the ADAS-cog, ADAS-non-cog and MMSE tests has been proven to occur as a function of the SG-135 dose (136).

The groups treated with the higher dose exhibited an improvement in cognitive improvement as early as at 12 weeks, which was sustained for 24 weeks of follow-up. The SG-treated patients also exhibited an improving trend over time. Improvement in cognitive function following SG treatment supports the findings that ginsenosides Rg3(R), Rg3(S) and Rg5/Rk1 exert memory-enhancing effects due to their neuroprotective actions against excitotoxicity (136).

Yang et al (137) investigated the neuroprotective and antioxidant effects of ginsenoside compound K (CK) on a mouse model of memory impairment induced by scopolamine hydrobromide. It should be noted that protopanaxadiol saponin is degraded by the intestinal flora into ginsenoside CK (20-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-20-(S)-protopanaxadiol) (CK). The role of CK in the regulation of Aβ and its ability to activate the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway have also been studied due to their great significance for AD. It has been proven that ginsenoside CK improves memory function, inhibits the expression of Aβ and activates the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway in animals exposed to scopolamine. Based on these results, Yang et al (137) concluded that ginsenoside CK can improve memory function by regulating Aβ aggregation and facilitating the transduction of the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway, thereby reducing oxidative damage to neurons and inhibiting neuronal apoptosis. Rg3 is the most effective ginsenoside having an Aβ-lowering effect, and the effect is correlated with the dose of Rg3. Similarly, Heo et al observed dose-related cognitive improvements following SG treatment (136).

Of note, Korean white ginseng root powder was previously shown to improve the performance of the ADAS-cog and MMSE tests. However, the ADAS-non-cog test scores remained unaltered, and the test scores evened out with those of the control group after the drug was discontinued (138). An increase in indicators was only found in the ADAS-cog and CDR tests, while the indicators of the ADAS-non-cog and MMSE tests were the same as those of the control group in a similar study using Korean red ginseng (KRG) root powder (139). Moreover, electroencephalography was used to assess the effectiveness of KRG root powder in relation to cognitive functions. An increase in relative alpha power was found in patients with AD who were treated with KRG root powder, which indicates an improvement in the functions of the frontal lobe. The FAB test scores also increased, although the MMSE scores remained unaltered (140).

In a different study, cognitive functions were assessed every 12 weeks, using the ADAS and the Korean version of the Mini-mental status examination (K-MMSE), to investigate maintenance doses of 4.5 and 9.0 g of KRG per day (141). A significant improvement was observed in groups that took KRG for 24 weeks. The improved MMSE score did not exhibit significant decreases at the 48th and 96th week, in a long-term assessment of the impact effectiveness of KRG. Similar results were obtained in the ADAS-assessment. The maximum improvement was found on the 24th week (141).

In another study, improved cognitive function was demonstrated with KRG treatment as was the sustainability of the achieved clinical goals in patients with AD. Previously, data on the long-term effects of KRG in patients with AD were limited, and studies did not exceed a few months (138), meaning that these shorter-term studies did not exactly indicate whether the effect of ginseng is temporary or whether it is able to continue to suppress the progressive course of AD. The results obtained in the long-term KRG study indicated that the effectiveness of KRG on cognitive function during the course of AD can be maintained for at least 2 years (141).

Several long-term (over 2 years) tests on AChE inhibitors have demonstrated that, although the efficacy of the drugs is evident, they were not able to block or reverse cognitive decline (142,143). The 2-year MMSE decline typically ranged from 2.5 to 4.0 points compared to the initial estimate. The usual picture of cognitive decline shows an initial improvement of 3 or 6 months, and then decreases to baseline over about a year in patients taking conventional medication. The disease then progresses again. By contrast, the ADAS-cog and K-MMSE scores were stable and did not exhibit an obvious decrease at the registration times over 2 years (141). This clinical picture can be explained by the difference in the main mechanisms of action of ginseng and anticholinesterase. The effect of ginseng on cognitive function with underlying specific mechanisms of influence has been considered (144). It is known that ginsenoside Rb1 improves learning and memory in tasks that are dependent on the hippocampus, and that it increases cell survival in the dentate gyrus of the medial and lower hemispheres of the large brain and in the hippocampal subregion CA3 (145). Ginsenoside Rg1 has been observed to weaken Aβ1-42-induced neurotoxicity and τ-hyperphosphorylation, in a dose-dependent manner, at several sites that are associated with AD (146). Moreover, it has been suggested that ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1 potentiate cholinergic pathways in the central nervous system and it was found that both ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 enhance the activity of ChAT and inhibit the activity of AChE, thereby enhancing the function of the cholinergic system (147).

The introduction of Rg1 and Rb1 to mice in the post-weaning period has been shown to increase the thickness and density of the cerebral cortex in the CA3 region of the hippocampus, which is believed to modulate synaptic plasticity, regarded as one of the most important learning and memory mechanisms (148).

12. Conclusion

We herein present a literature survey on the ginseng components that have exhibited biological activity on the pathogenesis of AD. Information on the effects of ginseng components on the signs of AD is depicted in Table III. The same symptoms that are observed in patients with AD are artificially created in animal models of AD; the mechanisms that trigger AD have not yet been confirmed with all possible accuracy. However, BAS found in ginseng can have a significant protective and inhibitory effect on the further development of AD, as shown by the foregoing review and general research data, summarized in Table III. The data obtained in studies on the effects of ginseng components on patients with AD have shown that ginseng preparations can be used for maintenance therapy. At the same time, a drug that consists of correctly selected ratios of the various components of ginseng is likely to be more effective than a simple ginseng root extract. However, the creation of such a drug will entail large-scale studies on the effects of individual components of ginseng on patients with AD.

Table III.

Effect of the components of ginseng on the pathogenesis of AD.

| Model AD | Treatment | Research results | Authors/(Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme activity measurement (without models) | Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Re, Rg1 and Rg3 | ↓ Activity AChE (except Rc); ↓ Activity BChE (except Rc and Re); ↓ Activity BACE1 (except Rg3 and Re); Neutralization of pyroxynitrite; ↓ Nitrotyrosine formation; | Shin et al (38) |

| Rat PC12 cells; Introduction Aβ25-35 | Extract Panax japonicus | 5 Components that are inhibitors of AChE were selected | Li et al (37) |

| Male ICR mice (6 weeks); Intracerebroventricular injection Aβ1-42 | Cereboost™ (extract Panax quinquefolius) | ↑ Cognitive abilities of mice; ↓ Activity AChE; ↓ Cytotoxicity Aβ1-42 in stem cell; ↑ Expression ChAT; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Level MAP2; ↑ Synaptophysin level; ↑ ACh level; | Li et al (103) |

| Wistar rats Streptozocin administration | Ginsenoside Rg5 | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↑ Expression BDNF; ↑ Expression IGF-1; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↓ Activity AChE; ↑ Activity ChAT; ↓ Level TNF-α; ↓ Level IL-1β; ↑ Expression COX-2; ↓ Expression NOS2; | Chu et al (41) |

| ICR male mice (7 weeks, 30–33 g); Intragypocampal injection AβO | White ginseng root extract (age 4 years) | Suppression of the activation of microglia; ↑ Memory function in mice; ↓ Neuron death; ↑ Cholinergic degeneration in the hippocampus | Choi et al (42) |

| N2a/APP695 cell line; | Ginsenoside Re | ↓ Substance production Aβ; Activation PPARγ; ↓ Activity BACE1; | Cao et al (49) |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats Intragypocampal injection Aβ1-42 | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Expression IDE; Activation PPARγ | Quan et al (50) |

| Female rats with ovaries removed (280–300 g) HT22 hippocampal neuronal cell line expressing ER | Ginsenoside Rd | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↓Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Level sAPPα; ↑Activity of signalling pathway MAPK/ERK; ↑ Activity of signalling pathway PI3K/AKT; ↑ Expression α-secretase; ↓ Expression BACE1; ↑ Level p-ERK, total level ERK was not altered; ↑ Level p-AKT, total level AKT was not altered; ↑ Expression p-ERα, total expression ERα, ERβ levels not altered; | Yan et al (51) |

| Line of neuronal cells of the hippocampus HT22 Human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↑ Level sAPPα; ↑ Activity α- secretase; | Shi et al (52) |

| Female Wistar rats with ovaries removed (9 months) | ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Level p-ERK and ERK; ↑ Level p-AKT and AKT; ↑ Expression p-ERα and ERα; | ||

| 12 women with menopause Platelet rich plasma taken | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↑ Level sAPPα; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Activity α- secretase; ↑ Level p-ERK1/2, without affecting the overall level ERK1/2; | Shi et al (53) |

| Female Wistar rats (10 weeks, 260–300 g) Ovarian removal Injection of D-galactose | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↓ Generation Aβ1-42; ↓ Activity caspase-3; ↓ Cell apoptosis; ↑ Expression ADAM10; ↓ Expression BACE1; | Zhang et al (54) |

| Mice SAP8 (with elevated level APP and Aβ1-42) | Saponins from Panax notoginseng | ↑ Activity α-secretase; ↓ Activity BACE1; Activity of γ-secretase was not altered | Huang et al (55) |

| Cortical neurons from mouse embryos Tg2576 | Ginsenoside Rh2 | ↑ Cognitive abilities of mice; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; Activity of α-secretase and BACE1 was not altered; ↑ Level sAPPα; Total level of APP was not altered; ↑ Cholesterol level in neurons; | Qiu et al (58) |

| Neuronal differentiated mouse embryonic stem cells Transgenic APP/PSI mice | Ginsenoside Rg3 | ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Activity of PI4KIIα; | Kang et al (64) |

| Human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y Transgenic mice (with elevated level Aβ1-42) | Gintonin (glyco-lipoprotein fraction of ginseng extract) | ↑ Activity LPAR ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↑ Level sAPPα; ↓ Cytotoxicity Aβ1-42 in cells; ↑ Cognitive abilities of mice; ↓ Microglial activation; | Hwang et al (89) |

| Cell PC12 Injection Aβ25-35 | Ginsenoside Rg2 | ↑ Cell viability; ↓ Level LDH; ↓ Level ROS; ↓ Intracellular level Ca2+; ↓ Activity of caspase-3; ↑ Ratio Bcl-2/Bax; ↑ Level p-Akt; ↓ Cytotoxicity Aβ1-42 in cells; | Cui et al (95) |

| Cells PC12 Injection of glutamate | Ginsenoside Rg2 | ↑ Neuroprotective properties; ↓ Intracellular level Ca2+; ↓ Level MDA; ↓ Level NO; ↓ Level Aβ1-42; ↓ Expression caspase-3; ↓ Expression calpain II; | Li et al (96) |

| Primary cortical neurons Sprague-Dawley rats Injection Aβ25-35 | Ginsenoside Rb1 | ↓ Level p-tau; ↓ Cytotoxicity Aβ25-35 in cells; ↓ Level and expression CDK5; ↓ Calpain activity; ↓ Intracellular level Ca2+; | Chen et al (97) |

| SD rats Aβ25-35 injection | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↓ Current density through high-threshold calcium channels through MAPK; | Quan et al (98) |

| Female Wistar rats (3 months), Tg APP/PSI rats | Ginsenoside Rg1 | ↓ Accumulation of NFTs; ↓ Level of Aβ1-42; ↓ Apoptosis; ↓ Expression of IRE-1; ↓ Expression of TRAF2; ↓ Expression of p-JNK; | Mu et al (81) |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats Intragypocampal injection Aβ1-42 Liu J | Ginsenoside Rd | ↑ Cognitive abilities of rats; ↑ Neuroprotective properties; ↓ Cytotoxicity of Aβ1-42; ↓ Expression IL-1β; ↓ Level and expression of IL-6; ↑ Level and expression of IL-10; ↓ Level and expression of TNF-α; ↑ Expression of HSP70; ↓Ratio of GSSG/GSH; ↓ Expression of caspase-3; | Liu et al (87) |

| Primary cortical neurons from the brain of newborn (0–24 h) mice; | Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer root extract (aged 4 years) | ↑ Survival rate ↓ Neuronal apoptosis in vitro; ↑ Ratio of expression p-PKA/PKA and p-CREB/CREB; | Li et al (103) |

| Female rats (260–280 g); Injection of D-galactose and aluminum chloride | ↓ Concentration of MDA; ↓ Concentration of NO; ↑ Ratio of Bcl-2/Bax; ↓ Expression of caspase-3; ↓ Level of p-Tau; ↑ Activity of SOD; ↓ Activity of NOS2 and NOS; ↑ Level of cAMP; | ||

| Cortical cortical neurons (PC12 cells) | Radix Notoginseng flavonol glycoside (RNFG), quercetin 3-O-β-D-xylo-pyranosyl-β-D-galactopyranoside | ↓ Cytotoxicity Aβ1-42 in cells; ↓ Level of Aβ1-42; ↓ Level of ROS; | Choi et al (104) |