Abstract

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary bone malignancy. It predominantly occurs in adolescents, but can develop at any age. The age at diagnosis is a prognostic factor of OS, but the molecular basis of this remains unknown. The current study aimed to identify age-induced differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and potential molecular mechanisms that contribute to the different outcomes of patients with OS. Microarray data (GSE39058 and GSE39040) obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database and used to analyze age-induced DEGs to reveal molecular mechanism of OS among different age groups (<20 and >20 years old). Differentially expressed mRNAs (DEMs) were divided into up and downregulated DEMs (according to the expression fold change), then Gene Ontology function enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis were performed. Furthermore, the interactions among proteins encoded by DEMs were integrated with prediction for microRNA-mRNA interactions to construct a regulatory network. The key subnetwork was extracted and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for a key microRNA was performed. DEMs within the subnetwork were predominantly involved in ‘ubiquitin protein ligase binding’, ‘response to growth factor’, ‘regulation of type I interferon production’, ‘response to decreased oxygen levels’, ‘voltage-gated potassium channel complex’, ‘synapse part’, ‘regulation of stem cell proliferation’. In summary, integrated bioinformatics was applied to analyze the potential molecular mechanisms leading to different outcomes of patients with OS among different age groups. The hub genes within the key subnetwork may have crucial roles in the different outcomes associated with age and require further analysis.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, age, Gene Expression Omnibus data, integrated bioinformatics, regulatory network

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS), the most common primary malignancy of bone, can occur at any age, but predominantly develops in adolescents, with ~400 newly diagnosed cases each year in America (1). OS accounts for ~60% of all bone malignancies diagnosed in patients <20 years old (2,3). Several studies reported that disease stage, gender, age, pathology subtypes and primary tumor site of OS result in differences in survival rate, with younger patients exhibiting significant better prognosis and higher survival rate than the elderly (2,4). With improved chemotherapy outcomes in the 1980s, the 5-year event-free survival was significantly increased, whereas it has remained stable without any significant improvement in the past 20 years (5–7). Uncovering the tumorigenesis and progression mechanisms is crucial for developing effective molecular targeted therapy. In the past decades, efforts have been made to clarify the molecular basis of OS. Substantial progress has been made using gene expression profiles of OS to reveal the molecular pathogenesis of OS. Age is a prognostic factor of OS insofar as we know; however, few studies have investigated the underlying molecular mechanisms, which may contribute to various outcomes.

Original microarray datasets of 36 OS samples from patients aged <20 and 6 matched samples aged >20 (GSE39058) (8), and 58 OS samples from patients aged <20 and 7 matched samples from patients aged >20 from human non-coding RNA profiling data (GSE39040) (8), were obtained from the human expression database Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between OS cases aged <20 and matched cases aged >20 were screened using R software limma package (9). Gene function analysis, including Gene Ontology (GO) and KOBAS-Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways, were performed using the differentially expressed mRNAs on Metascape (http://metascape.org/gp/). A regulatory network was constructed by combining the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network with microRNA (miRNA)-mRNA interactions to reveal the potential molecular differences between the different age groups. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was also performed to clarify our result. In conclusion, the regulatory networks were constructed and the potential important key signaling pathways were analyzed by applying bioinformatics tools to investigate different molecular mechanism of OS among different age groups.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

Microarray data was retrieved from the GSE39058 and GSE39040 GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The mRNA expression of 36 OS samples from patients aged <20 and 6 matched samples from patients aged >20 obtained from GSE39058, based on the GPL14951 Illumina HumanHT-12 WG-DASL V4.0 R2 expression BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Similarly, a total of 58 OS samples from patients aged <20 and 7 matched samples from patients aged >20 were available in GSE39040, based on the GPL15762 Illumina Human v2 MicroRNA Expression BeadChip.

Data processing

Following background correction and quartile data normalization of the original microarray data by using the robust multi-array average algorithm, probes without a corresponding gene symbol were filtered and the average value of gene symbols with multiple probes was calculated. The selected data from GSE39058 and GSE39040 were compared using R software limma package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) to determine the differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs (10). With a threshold of P<0.05 and |log2(fold change)|>1, volcano plot filtering was performed by using R software ggplot2 package v2.2 (11) to identify the DEGs with statistical significance between two groups. Hierarchical clustering and combined analyses were performed for the DEGs. The differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs obtained were described as age-induced osteosarcoma DEMs and DEMis.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEMs

DEMs were converted to their corresponding Homo sapiens Entrez gene IDs using the latest database (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene; updated on 2018-01-01); pathway and process enrichment analysis of DEMs was performed using Metascape (metascape.org). All genes in the genome were used as the enrichment background. Terms with P<0.05 were statistically significant. Those with a minimum count of 3 and enrichment factor >1.5 (enrichment factor is the ratio between observed count and the count expected by chance) were collected, and grouped into clusters based on their membership similarities. More specifically, P-values were calculated based on accumulative hypergeometric distribution, q-values were calculated using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to account for multiple testing. κ scores were used as the similarity metric when performing hierachical clustering on the enriched terms and then sub-trees with similarity >0.3 were considered a cluster. The most statistically significant term within a cluster was selected to represent the cluster.

Regulatory network construction and analysis

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (string-db.org/) was used to explore the interactions among proteins encoded by the DEMs, including known proteins interactions and predicted interactions. The results were downloaded from the STRING database as a TSV file, the PPI pairs with selected larger scores were imported to the Cytoscape tool v3.4.0 (cytoscape.org/) to establish PPI network. The regulatory relationship between genes were analyzed through topological property of computing network including the degree distribution of network by using the CentiScaPe2.2 app within Cytoscape (12). The interaction between DEMs and DEMis was predicted using miRwalk v3.0 (mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) with a threshold of energy <-20, and only the interactions of miRNA and mRNA with opposite expression were included. Furthermore, the regulatory network was constructed by combining the PPI network with the predicted interactions between DEMs and DEMis. The subnetwork was extracted from the whole PPI network using the MCODE app v1.5.1 (13).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

In the present study, the prognostic value of the genes was confirmed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis based on the clinical information from the GSE39040 dataset using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For statistical analysis, the patients were divided into halves based on gene expression values. Specifically, patients with the expression values greater than the median value were classified as the high expression group and others classified as the low expression group. Log rank test (Mantel-Cox test) was used to evaluate the prognostic value of the genes.

Results

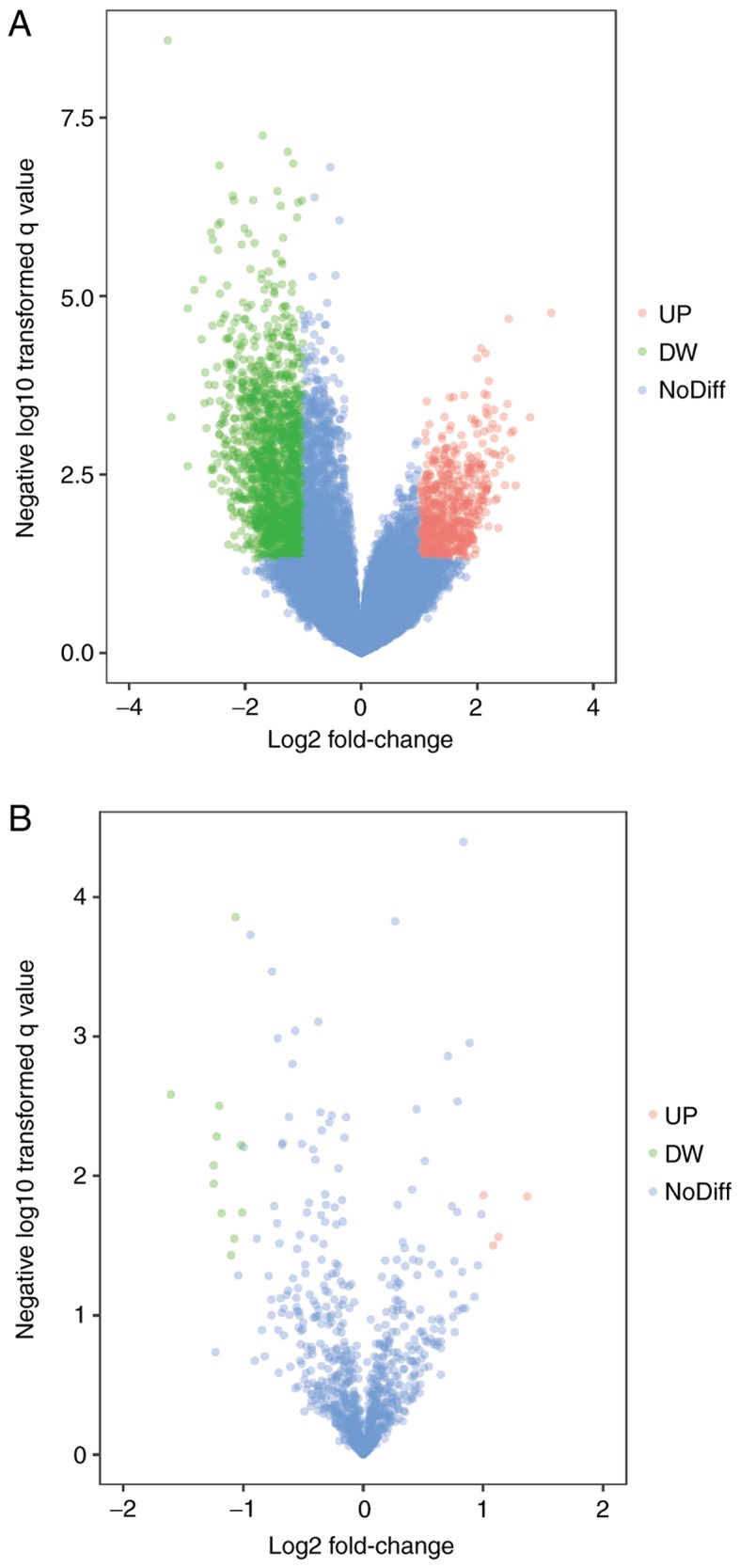

Data processing and DEG screening

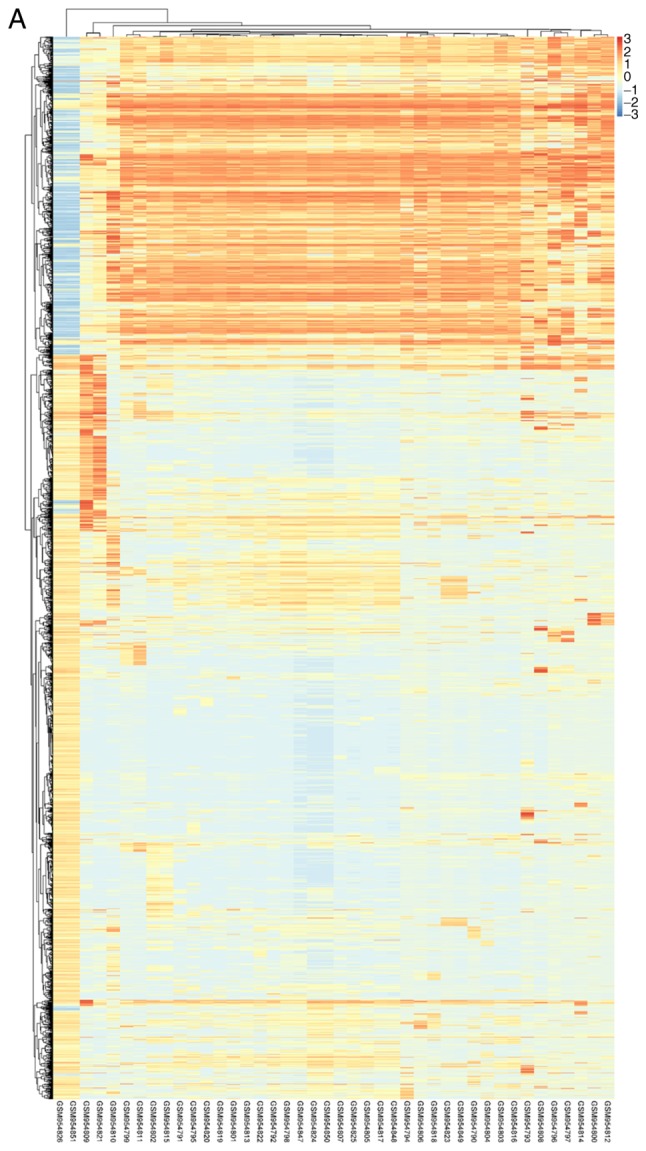

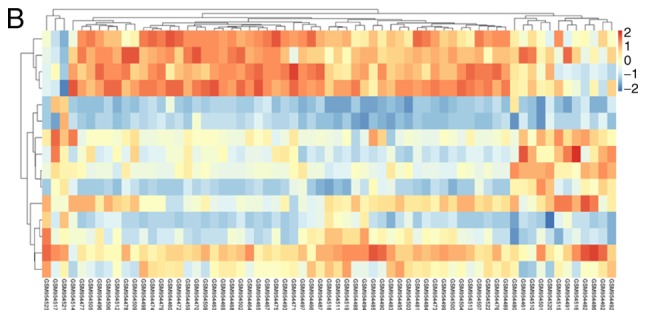

DEMs of GSE39058 were obtained using R software limma package with |log2(fold change)|>1 and P<0.05 as the cut-off point. In OS samples from patients aged <20, there were 1,476 up-regulated DEMs, corresponding to 1,525 probes and 637 downregulated DEMs detected by 650 probes in OS samples from patients aged <20 compared with OS samples from patients aged >20. The top 10 most significantly upregulated genes were SNORA17, SNORD3C, CRY1, TSEN34, NDUFA12, CNTFR, CPE, PTGS2, NKD2 and EGFL6. The top 10 most significantly downregulated genes were PPP2R2B, DSCR8, ALAS2, GPR114, NPLOC4, PDE7B, NCOA2, MRFAP1L1, LIG3 and RUNX1. Similarly, there were 15 DEMis in GSE39040, including 11 downregulated and 4 upregulated DEMis OS samples from patients aged <20 compared with OS samples from patients aged >20. The DEMis upregulated in OS samples from patients aged <20 were hsa-miR-1248, hsa-miR-497, hsa-miR-1201 and hsa-miR-224. The downregulated DEMis were hsa-miR-122, hsa-miR-203, hsa-miR-205, hsa-miR-194, hsa-miR-200c, hsa-miR-183, hsa-miR-142-5p, hsa-miR-182, hsa-miR-549, hsa-miR-202* and hsa-miR-515-5p. The volcano plot of each microarray is presented in Fig. 1 to visualize DEGs. Fig. 2 presented the cluster heatmaps of DEMs and DEMis.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed genes between two sets of samples. (A) GSE39058 data, (B) GSE39040 data. The red points represent upregulated genes screened on the basis of |fold change|<2.0 and P<0.05. The green points represent downregulated genes screened on the basis of |fold change|<2.0 and P<0.05. The blue points represent genes with no significant difference. UP, upregulated; DW, downregulated; NoDiff, no significant difference.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering heatmap of DEGs screened on the basis of log2(fold change) <2.0 and P<0.05. (A) GSE39058, (B) GSE39040. Orange indicates that the expression of genes is relatively upregulated; blue indicates that the expression of genes is relatively downregulated, and white indicates no significant difference.

DEMs enrichment analysis

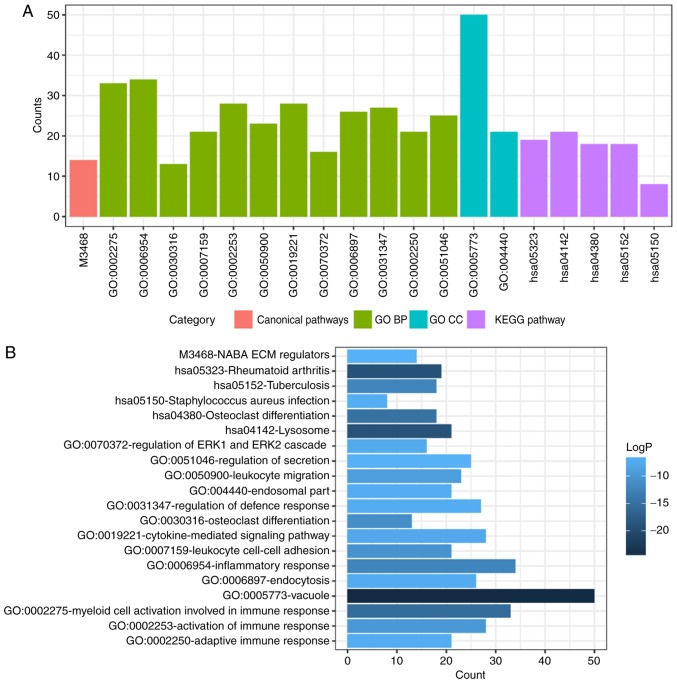

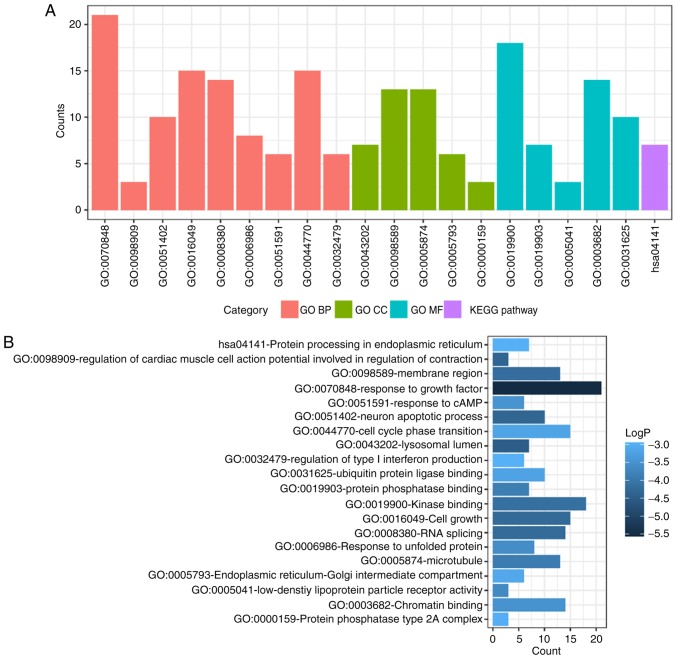

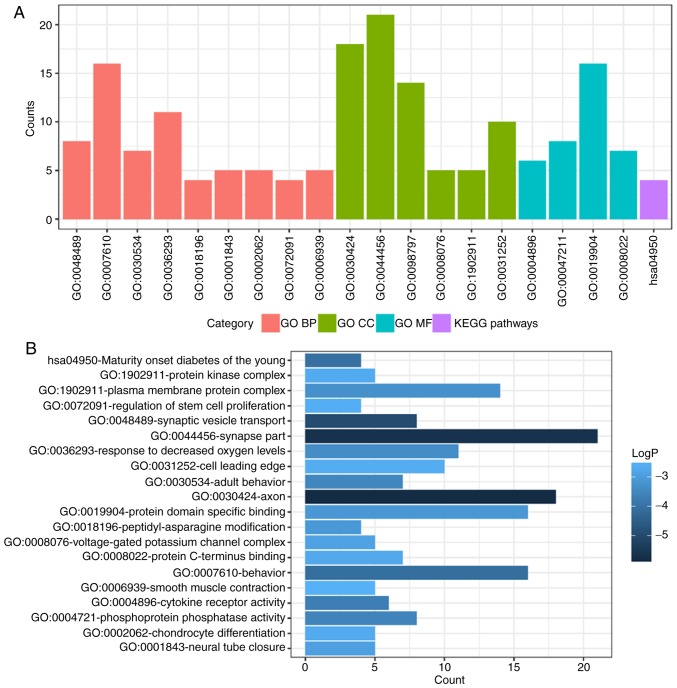

To determine functional enrichment, Metascape was used for GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMs. GO functional enrichments and KEGG pathways of which P<0.05 were selected as significant results (Table I). GO analysis of DEGs includes three functional groups, namely molecular function, biological processes and cellular component. The significant GO enrichment analysis of all DEMs is presented in Fig. 3. GO functional enrichments and KEGG pathway analysis of up- and down-regulated DEMs were also performed using Metascape. The significant results (P<0.05) are presented in Figs. 4 and 5, with details information in Tables II and III. Upregulated DEMs were predominantly involved in the ‘cell growth’, ‘response to growth factor’ and ‘neuron apoptotic process’ and ‘activation of immune response’. The downregulated DEMs were mainly involved in ‘cytokine receptor activity’, ‘phosphoprotein phosphatase activity’, ‘response to decreased oxygen levels’ and ‘regulation of stem cell proliferation’.

Table I.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed mRNAs.

| Category | Term | Description | Count | LogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical pathways | M3468 | NABA ECM REGULATORS | 14 | −6.64807 |

| GO BP | GO:0002275 | Myeloid cell activation involved in immune response | 33 | −15.539 |

| GO BP | GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 34 | −12.1737 |

| GO BP | GO:0030316 | Osteoclast differentiation | 13 | −11.0649 |

| GO BP | GO:0007159 | Leukocyte cell-cell adhesion | 21 | −10.3439 |

| GO BP | GO:0002253 | Activation of immune response | 28 | −9.66921 |

| GO BP | GO:0050900 | Leukocyte migration | 23 | −9.04039 |

| GO BP | GO:0019221 | Cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | 28 | −7.7241 |

| GO BP | GO:0070372 | Regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade | 16 | −7.41007 |

| GO BP | GO:0006897 | Endocytosis | 26 | −7.22687 |

| GO BP | GO:0031347 | Regulation of defense response | 27 | −7.11793 |

| GO BP | GO:0002250 | Adaptive immune response | 21 | −7.0625 |

| GO BP | GO:0051046 | Regulation of secretion | 25 | −6.61093 |

| GO CC | GO:0005773 | Vacuole | 50 | −24.946 |

| GO CC | GO:0044440 | Endosomal part | 21 | −7.19392 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa05323 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 19 | −19.1021 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa04142 | Lysosome | 21 | −19.026 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa04380 | Osteoclast differentiation | 18 | −14.6982 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa05152 | Tuberculosis | 18 | −12.2416 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa05150 | Staphylococcus aureus infection | 8 | −6.94145 |

GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ECM, extracellular matrix; ERK, extracellular signal regulated-kinase; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component.

Figure 3.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEMs. (A) GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis divided DEMs into four functional groups. (B) Statistical significance of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of DEMs in different functional groups. DEMs, differentially-expressed mRNAs; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ECM, extracellular matrix; ERK, extracellular signal regulated-kinase.

Figure 4.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of upregulated DEMs. (A) GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis divided DEMs into four functional groups. (B) Statistical significance of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of DEMs in different functional groups. DEMs, differentially-expressed mRNAs; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Figure 5.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of downregulated DEMs. (A) GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis divided DEMs into four functional groups. (B) Statistical significance of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of DEMs in different functional groups. DEMs, differentially-expressed mRNAs; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Table II.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the upregulated differentially expressed mRNAs.

| Category | Term | Description | Count | LogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO BP | GO:0070848 | Response to growth factor | 21 | −5.5332 |

| GO BP | GO:0098909 | Regulation of cardiac muscle cell action potential involved in regulation of contraction | 3 | −4.34678 |

| GO BP | GO:0051402 | Neuron apoptotic process | 10 | −4.32756 |

| GO BP | GO:0016049 | Cell growth | 15 | −4.25172 |

| GO BP | GO:0008380 | RNA splicing | 14 | −4.23503 |

| GO BP | GO:0006986 | Response to unfolded protein | 8 | −3.60467 |

| GO BP | GO:0051591 | Response to cAMP | 6 | −3.46953 |

| GO BP | GO:0044770 | Cell cycle phase transition | 15 | −3.20217 |

| GO BP | GO:0032479 | Regulation of type I interferon production | 6 | −2.96638 |

| GO CC | GO:0043202 | Lysosomal lumen | 7 | −4.47707 |

| GO CC | GO:0098589 | Membrane region | 13 | −4.16789 |

| GO CC | GO:0005874 | Microtubule | 13 | −3.91148 |

| GO CC | GO:0005793 | Endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment | 6 | −3.11995 |

| GO CC | GO:0000159 | Protein phosphatase type 2A complex | 3 | −3.01052 |

| GO MF | GO:0019900 | Kinase binding | 18 | −4.1399 |

| GO MF | GO:0019903 | Protein phosphatase binding | 7 | −3.87788 |

| GO MF | GO:0005041 | Low-density lipoprotein particle receptor activity | 3 | −3.65378 |

| GO MF | GO:0003682 | Chromatin binding | 14 | −3.49506 |

| GO MF | GO:0031625 | Ubiquitin protein ligase binding | 10 | −3.22244 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa04141 | Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 7 | −2.98232 |

GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular functions.

Table III.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the downregulated differentially expressed mRNAs.

| Category | Term | Description | Count | LogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO BP | GO:0048489 | Synaptic vesicle transport | 8 | −4.97563 |

| GO BP | GO:0007610 | Behavior | 16 | −4.08991 |

| GO BP | GO:0030534 | Adult behavior | 7 | −3.49616 |

| GO BP | GO:0036293 | Response to decreased oxygen levels | 11 | −3.35132 |

| GO BP | GO:0018196 | Peptidyl-asparagine modification | 4 | −3.07891 |

| GO BP | GO:0001843 | Neural tube closure | 5 | −2.90315 |

| GO BP | GO:0002062 | Chondrocyte differentiation | 5 | −2.67404 |

| GO BP | GO:0072091 | Regulation of stem cell proliferation | 4 | −2.59464 |

| GO BP | GO:0006939 | Smooth muscle contraction | 5 | −2.52575 |

| GO CC | GO:0030424 | Axon | 18 | −5.87109 |

| GO CC | GO:0044456 | Synapse part | 21 | −5.66372 |

| GO CC | GO:0098797 | Plasma membrane protein complex | 14 | −3.27326 |

| GO CC | GO:0008076 | Voltage-gated potassium channel complex | 5 | −2.85904 |

| GO CC | GO:1902911 | Protein kinase complex | 5 | −2.65473 |

| GO CC | GO:0031252 | Cell leading edge | 10 | −2.62652 |

| GO MF | GO:0004896 | Cytokine receptor activity | 6 | −3.68521 |

| GO MF | GO:0004721 | Phosphoprotein phosphatase activity | 8 | −3.57184 |

| GO MF | GO:0019904 | Protein domain specific binding | 16 | −3.127 |

| GO MF | GO:0008022 | Protein C-terminus binding | 7 | −2.72974 |

| KEGG pathway | hsa04950 | Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 4 | −4.05467 |

GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular functions.

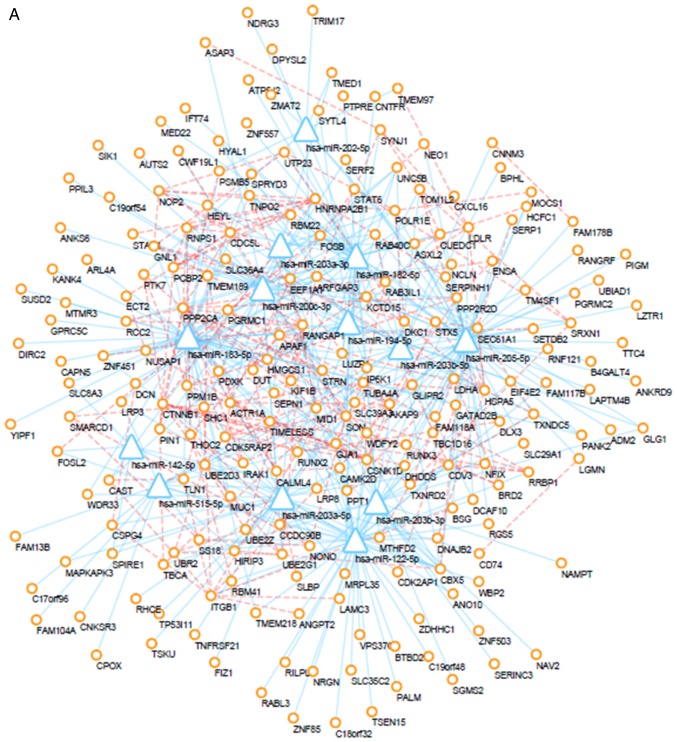

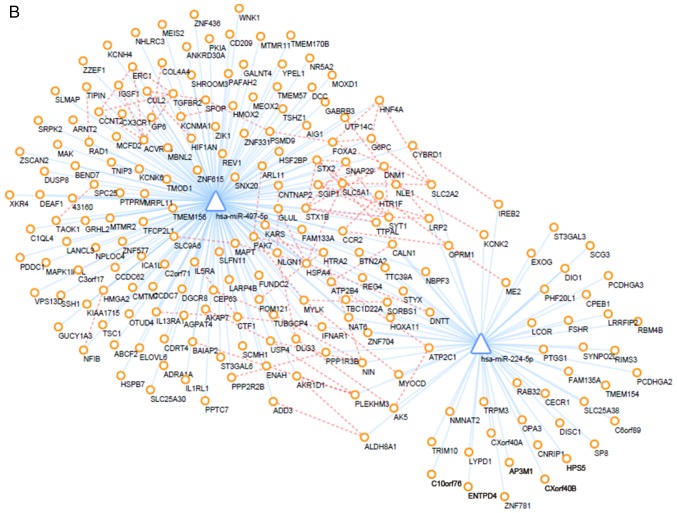

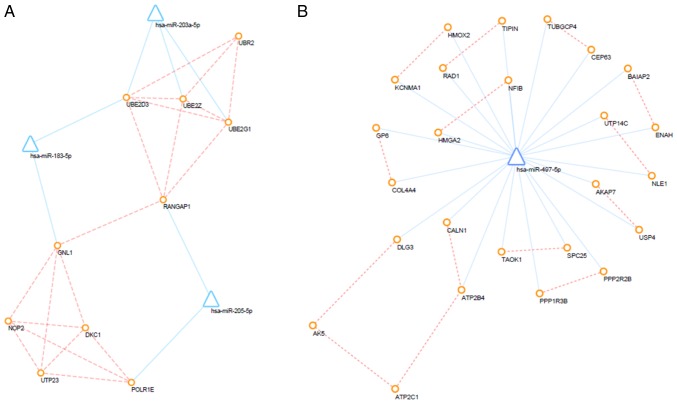

PPI network

The interactions between proteins encoded by DEMs were downloaded from the STRING database and a PPI network was created using the Cytoscape tool. Additionally, prediction of miRNA-mRNA interactions was integrated into the PPI network. After altering of the color and location of nodes, the PPI network was successfully established (Fig. 6). Furthermore, PPI networks of up- and down-regulated DEMs and their interacting DEMis were also constructed, and the key subnetwork was subsequently extracted using the MCODE app in Cytoscape (Fig. 7). The key significant genes were hsa-miR-497-5p, hsa-miR-203a-5p, hsa-miR-183-5p and hsa-miR-205-5p and the DEMs that they are known to interact with. Of note, up-regulated DEMs within the subnetwork were mainly involved in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPP), response to growth factors and the regulation of type I interferon production caused by the reduced expression levels of hsa-miR-203, hsa-miR-205 and hsa-miR-183. Furthermore, as a consequence of the overexpression of miR-497, downregulated DEMs within the hub subnetwork were closely associated with response to hypoxia, transport of potassium, activity of synapse, regulation of stem cell proliferation.

Figure 6.

Regulatory network. (A) Regulatory network of upregulated DEGs. (B) regulatory network of downregulated DEGs. Circles represent differentially expressed mRNAs, triangles represent differentially expressed microRNAs, blue lines represent microRNA/mRNA interactions, and orange dotted lines represent protein-protein interactions. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Figure 7.

Sub-regulatory network. (A) Sub-regulatory network of upregulated differentially expressed genes. (B) Sub-regulatory network of downregulated DEGs. Circles represent differentially expressed mRNAs, triangles represent differentially expressed microRNAs, blue lines represent microRNA/mRNA interactions, orange dotted lines represent protein-protein interactions.

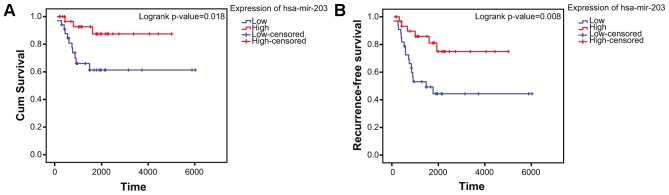

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

The clinical information was obtained from GSE39058 dataset. A total of 65 patients were included in the present study. The log-rank test confirmed that low expression of hsa-miR-203 (P=0.008411 and log2(fold change)=−1.247074) in aged cases was negatively associated with overall survival (Fig. 8A) and positively associated with recurrence rate (Fig. 8B) in patients with OS.

Figure 8.

Survival analysis. (A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of hsa-mir-203 expression level and overall survival of patients with osteosarcoma. (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of hsa-mir-203 expression level and recurrence rate of patients with osteosarcoma. hsa, Homo sapiens; miR, microRNA.

Discussion

In the current study, microarray data from the GEO database was used to analyze DEGs to reveal differences in molecular mechanism introduced by age. DEMs were divided into two groups by the log2(fold change), then GO function enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis were performed. Furthermore, an integrated regulatory network was generated by integrating the interactions of proteins encoded by DEMs with predictions of miRNA-mRNA interactions. The potential GO functional annotations and the upstream DEMis that may induce the difference in prognosis and survival rate among ages were identified.

From analyzing the key subnetwork combined with the function enrichment analysis, it was apparent that the upregulated DEMs within the key subnetwork were mostly involved in the UPP, response to growth factors and the regulation of type I interferon production. DEMs upregulation may be caused by the reduced expression of hsa-miR-203, hsa-miR-205 and hsa-miR-183. Downregulation of DEMs is potentially caused by upregulated expression of miR-497, and this subnetwork was associated with response to hypoxia, transport of potassium, activity of synapse, regulation of stem cell proliferation.

The UPP is essential for maintaining the homeostasis, as it is responsible for intracellular protein degradation. It has a critical role in many cellular processes, including cell cycle, cell differentiation, apoptosis, anti-apoptosis and tumor development (14–17). The upregulated DEMs enriched in UPP were ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 2 (UBR2), ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 (UBE2) G1, UBE2D3, UBE2Z and Ran GTPase activating protein 1. Of these DEMs, UBE2G1, UBE2D3 and UBE2Z were targets of hsa-miR-203, and hsa-miR-203 was previously demonstrated to be downregulated in OS in patients <20 years old in the current study compared with patients >20. UBR2, the sole known E3 ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway, is reported to be upregulated in colon adenocarcinoma and Lewis lung carcinoma (15). UBR2 is also demonstrated to have a pro-apoptotic function by degrading the anti-apoptotic form of tyrosine kinase Lyn, contradicting previous reports of an anti-apoptotic role, indicating that UBR2 might inhibit tumor initiation and progression (14). UBE2D3, a positive prognostic factor in cancer, inhibits cell proliferation and contributes to radiosensitivity, thus improving the survival time (18–20). These findings suggest that UBR2, UBE2G1, UBE2D3, UBE2Z and RANGAP1, which were enriched in UPP, may serve a negative role in the development and progression of cancer; the novel association between UBE2G1 and UBE2Z and cancer requires further investigation. Liu and Feng (21) reported that miR-203 was downregulated in OS tissues and cell lines, and was associated with poor survival of patients with OS. Most studies suggest that hsa-miR-203 acts as a tumor suppressor by repressing tumor growth and invasion, and downregulating hsa-miR-21; overexpression of hsa-miR-21 is described in several reported carcinogenic processes, such as invasion and metastasis and is closely associated with poor survival (21–23). However, Ikenaga et al (24) reported that hsa-miR-203 was overexpressed in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and was an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. These findings indicate that hsa-miR-203 has a complex role in cancer initiation and progression as miR-203 interacts with may mRNA targets. Thus, the precise mechanism of hsa-miR-203 in tumorigenesis and progression requires further research.

Hypoxia, which is associated with tumorigenesis, tumor development, invasion and metastasis, commonly occurs in rapidly growing solid tumors, while some studies have suggested that hypoxia is a common phenomenon in OS (25,26). Accumulating evidence suggests that hypoxia promotes tumorigenesis, tumor progression, invasion and migration (26–28). Heme oxygenase 2 and potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily M α 1 (KCNMA1), the downregulated DEM that was associated with response to hypoxia, may be potential target mRNAs of hsa-miR-497 and was both involved in potassium transport. It has been reported that miR-497, a hypoxia-inducible miRNA, which was suppressed in OS when compared with adjacent tissues, inhibits the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α and certain other genes (29,30). OS samples from patients aged <20 exhibited higher levels of miR-497 and reduced expression of downstream DEMs involved in the response to hypoxia, thus inhibiting tumor progression, which may be responsible for the improved survival of patients with OS aged <20.

The downregulated DEMs of potentially targeted by miR-497 in OS patients aged <20 were mainly involved in potassium transport included proteins of the potassium channel complex and transmembrane transporter complex, such as the Big Potassium (BK) ion channel, also termed KCNMA1, encoded by the DEM KCNMA1. BK channels in biological membranes facilitate the efflux of potassium from intracellular stores. Many ion channels promote cell proliferation, in including the BK channel (31–33). Several reports have demonstrated that BK channels have active roles in tumor growth and metastasis, and the development of drug resistance in glioma, breast cancer and prostate cancer (34–36); whereas Cambien et al (37) contradicted this by reporting that the genetic knockdown of BKα promoted OS progression. Furthermore, BK channel is also reported to promote breast cancer and glioma invasion and migration (38,39); however, there is limited evidence of the role of BK channel in OS invasion and metastasis. The findings of the current study that BK channels have a complex role in cell proliferation with numerous other factors involved. In the present study, BK channel-related genes were significantly downregulated in OS patients aged <20, who exhibited better prognosis. Thus, we hypothesized that the active BK channel may partly contribute to poorer survival.

Age is considered to be a prognostic factor in patients with OS; however, the differences in the molecular mechanisms of OS according to age are unclear. In the current study a regulatory network for OS was created by combining PPI network and miRNA-mRNA interactions, and finally we extracted the key subnetwork by topologic analysis. The study provides some insightful information to interpret why younger patients with OS have a far more positive outcome. Furthermore, certain genes may act as potential prognostic factors and effective drug targets for treatment were identified. However, further research is required to determine the exact roles of the identified genes in OS; further investigation into the role other hub miRNAs, including hsa-miR-497, hsa-miR-183 and hsa-miR-205 in the development of OS should be conducted in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- DEMs

differentially expressed mRNAs

- DEMis

differentially expressed microRNAs

- GO

Gene Ontology

- BP

biological process

- CC

cellular component

- MF

molecular functions

Funding

This study was supported by the Foundation of Shenzhen Health and Family Planning Commission (grant no. SZFZ2017081).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets we utilized are available in the GEO online database (accession number no. GSE39058 and GSE39040). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE39058; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE39040.

Authors' contributions

JMH and JSW designed the study. JSW analysed and interpreted the microarray profile downloaded from GEO database. MYD, SXD, PX and GZZ made substantial contributions to data analysis. JSW and MYD wrote the manuscript. YSZ and XDL performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. JMH was primarily responsible for writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sugalski AJ, Jiwani A, Ketchum NS, Cornell J, Williams R, Heim-Hall J, Hung JY, Langevin AM. Characterization of localized osteosarcoma of the extremity in children, adolescents, and young adults from a single institution in South Texas. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:e353–e358. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2009;115:1531–1543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A, O'Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, editors. NIH Pub. No 06-5767. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2006. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagleitner MM, Hoogerbrugge PM, van der Graaf WT, Flucke U, Schreuder HW, te Loo DM. Age as prognostic factor in patients with osteosarcoma. Bone. 2011;49:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Delling G, Exner GU, Flege S, Helmke K, Kotz R, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Werner M, Winkelmann W, et al. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: An analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:776–790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacci G, Longhi A, Versari M, Mercuri M, Briccoli A, Picci P. Prognostic factors for osteosarcoma of the extremity treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: 15-year experience in 789 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2006;106:1154–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelan JS, Jinks RC, McTiernan A, Sydes MR, Hook JM, Trani L, Uscinska B, Bramwell V, Lewis IJ, Nooij MA, et al. Survival from high-grade localised extremity osteosarcoma: Combined results and prognostic factors from three European Osteosarcoma Intergroup randomised controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly AD, Haibe-Kains B, Janeway KA, Hill KE, Howe E, Goldsmith J, Kurek K, Perez-Atayde AR, Francoeur N, Fan JB, et al. MicroRNA paraffin-based studies in osteosarcoma reveal reproducible independent prognostic profiles at 14q32. Genome Med. 2013;5:2. doi: 10.1186/gm406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diboun I, Wernisch L, Orengo CA, Koltzenburg M. Microarray analysis after RNA amplification can detect pronounced differences in gene expression using limma. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:252. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickham H, ggplot2 . Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 2016. Elegant graphics for data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scardoni G, Petterlini M, Laudanna C. Analyzing biological network parameters with CentiScaPe. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2857–2859. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldeeb MA, Fahlman RP. The anti-apoptotic form of tyrosine kinase Lyn that is generated by proteolysis is degraded by the N-end rule pathway. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2714–2722. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang G, Lin RK, Kwon YT, Li YP. Signaling mechanism of tumor cell-induced up-regulation of E3 ubiquitin ligase UBR2. FASEB J. 2013;27:2893–2901. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-222711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin TY, Lee CC, Chen KC, Lin CJ, Shih CM. Inhibition of RNA transportation induces glioma cell apoptosis via downregulation of RanGAP1 expression. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;232:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao J, Liang Z, Zhang B, Yang H, Li X, Fu H, Zhang X, Yan Y, Xu W, Qian H. UBR2 enriched in p53 deficient mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-exosome promoted gastric cancer progression via Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Stem Cells. 2017;35:2267–2279. doi: 10.1002/stem.2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan GG, Wang WB, Lei BX, Wang QL, Wu L, Fu ZM, Zhou FX, Zhou YF. UBE2D3 is a positive prognostic factor and is negatively correlated with hTERT expression in esophageal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1567–1574. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, Yang L, Hu L, Li F, Ren L, Yu H, Liu Y, Xia L, Lei H, Liao Z, et al. Inhibition of UBE2D3 expression attenuates radiosensitivity of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by increasing hTERT expression and activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Wang W, Yang H, Wu L, He Z, Zhou S, Zhao H, Fu Z, Zhou F, Zhou Y. UBE2D3 gene overexpression increases radiosensitivity of EC109 esophageal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo 7. 2016:32543–32553. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Feng P. MiR-203 determines poor outcome and suppresses tumor growth by targeting TBK1 in osteosarcoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:1956–1966. doi: 10.1159/000438556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang F, Yang Z, Cao M, Xu Y, Li J, Chen X, Gao Z, Xin J, Zhou S, Zhou Z, et al. MiR-203 suppresses tumor growth and invasion and down-regulates MiR-21 expression through repressing Ran in esophageal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;342:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: A small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikenaga N, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Yu J, Kayashima T, Sakai H, Fujita H, Nakata K, Tanaka M. MicroRNA-203 expression as a new prognostic marker of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3120–3128. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunz M, Ibrahim SM. Molecular responses to hypoxia in tumor cells. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo M, Cai C, Zhao G, Qiu X, Zhao H, Ma Q, Tian L, Li X, Hu Y, Liao B. Hypoxia promotes migration and induces CXCR4 expression via HIF-1alpha activation in human osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan G, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Liu L, Shi D, Wen Y, Yang L, Ma Q, Liu T, Zhu X, et al. The HIF-1alpha/CXCR4 pathway supports hypoxia-induced metastasis of human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao J, Wang Y, Dong R, Lin G, Zhang N, Wang J, Lin N, Gu Y, Ding L, Ying M, et al. Hypoxia-Induced WSB1 promotes the metastatic potential of osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4839–4851. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shan K, Pang R, Zhao C, Liu X, Gao W, Zhang J, Zhao D, Wang Y, Qiu W. IL-17-triggered downregulation of miR-497 results in high HIF-1alpha expression and consequent IL-1beta and IL-6 production by astrocytes in EAE mice. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Z, Cai X, Huang C, Xu J, Liu A. miR-497 suppresses angiogenesis in breast carcinoma by targeting HIF-1alpha. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:1696–16702. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH. Ion channels and transporters in the development of drug resistance in cancer cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20130109. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver AK, Liu X, Sontheimer H. Role for calcium-activated potassium channels (BK) in growth control of human malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:224–234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urrego D, Tomczak AP, Zahed F, Stühmer W, Pardo LA. Potassium channels in cell cycle and cell proliferation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20130094. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloch M, Ousingsawat J, Simon R, Schraml P, Gasser TC, Mihatsch MJ, Kunzelmann K, Bubendorf L. KCNMA1 gene amplification promotes tumor cell proliferation in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2525–2534. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oeggerli M, Tian Y, Ruiz C, Wijker B, Sauter G, Obermann E, Güth U, Zlobec I, Sausbier M, Kunzelmann K, Bubendorf L. Role of KCNMA1 in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bury M, Girault A, Mégalizzi V, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Mathieu V, Berger W, Evidente A, Kornienko A, Gailly P, Vandier C, Kiss R. Ophiobolin A induces paraptosis-like cell death in human glioblastoma cells by decreasing BKCa channel activity. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e561. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cambien B, Rezzonico R, Vitale S, Rouzaire-Dubois B, Dubois JM, Barthel R, Soilihi BK, Mograbi B, Schmid-Alliana A, Schmid-Antomarchi H. Silencing of hSlo potassium channels in human osteosarcoma cells promotes tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:365–371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khaitan D, Sankpal UT, Weksler B, Meister EA, Romero IA, Couraud PO, Ningaraj NS. Role of KCNMA1 gene in breast cancer invasion and metastasis to brain. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sontheimer H. An unexpected role for ion channels in brain tumor metastasis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:779–791. doi: 10.3181/0711-MR-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets we utilized are available in the GEO online database (accession number no. GSE39058 and GSE39040). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE39058; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE39040.