Abstract

Background:

Previous studies suggest that various factors including the type of occupation, employment status, and level of education have significant associations with the rates of occupational injuries. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of demographics, such as age and gender, and various occupational factors on the rate of occupational injuries for a 14-year period from 2001 to 2014 and to study the differences in trends over time.

Methods:

The Canadian Community Health Survey data for 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009–2014 was used to examine the impact of various occupational factors on workplace injuries in the Canadian population. Various inclusion criteria such as age, employment type, and status were applied to select the final sample. The logistic regression was performed using StataMP 11 to determine the association between the rate of occupational injuries and the factors being considered.

Results:

Rates of injuries occurring at the workplace are associated with various occupational health factors, including, the type of occupation, level of education, the number of injuries sustained, and the employment status.

Conclusion:

The findings may be used by researchers and practitioners to address the impact of occupational injuries in the workforce, and to identify and resolve the factors that result in a high rate of workplace injuries.

Key Words: Canada, Canadian community health survey, occupational injuries, workforce

INTRODUCTION

Injuries sustained at work have significant consequences in and out of the workplace. Such negative outcomes among many others include decreased work productivity and impaired work performance, as well as other indirect consequences such as an increase in the cost of medical expenses due to employees seeking compensations. A US study suggested that occupational injuries led to a total of 4700 deaths in 2011 which was estimated to cost the US economy approximately $6 billion alone.[1] Another study on the global trends of occupational health suggests that over 350,000 annual fatal occupational injuries occur globally; in 2010 alone, there were 313 million nonfatal occupational injuries, adding up to a minimum of 4 days of absence from work.[2]

Injuries occurring at work have been associated with both the type of work and the actions of workers.[3,4] According to a theoretical model of occupational injuries, various factors such as poor work conditions, tasks involving exposure to hazards, employment status (working part time or overtime), and individual characteristics such as demographics and the presence of a chronic disease, all combine to increase the risk of occupational injuries.[4] Despite the implementation of preventative measures in act, occupational injuries are still prevalent across many different work industries;[3] however, their rates across work various industries are not constant, and these results may vary depending on the demographics, and the occupational factors that are associated with the injuries.

There are limitations within Canadian studies that can fully assess the association and impact of specific occupational variables on the rates of occupational injuries; these variables include the type of occupation, employment status, number of injuries, chronic condition, and the level of education. Moreover, work-related injuries defined as injuries that occurred at or within the workplace and not as a result of intention (self-harm). For instance, the Association of Workers' Compensation Boards of Canada refers to a time-loss injury as “an injury for which a worker is compensated for a loss of wages following a work-related accident (or exposure to a noxious chemical) or receives compensation for a permanent disability with or without time lost in his or her employment,”[5] any other type of work injury that does not qualify the criteria for a wage compensation might be overlooked. This can cause disparities as the true burdens of occupational injuries may be underestimated: The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) includes injuries such as multiple minor injuries, or fractured bones that may not result in a loss of wage compared to other similar injuries such as broken bones, and therefore may be neglected. Furthermore, the CCHS is nationally administered and includes injuries that were not deemed lost time or reported to a worker's compensation board. Owing to the widespread prevalence and economic and social impact of both major and minor injuries, we found it worthwhile to assess consistent factors that may lead to a high rate of occupational injuries. These results of our assessment are important in identifying the occupational factors that might contribute to a higher rate of injuries compared to the others and therefore might require an allocation of a higher number of resources and/or precautionary measures to minimize if not eliminate the sources of error.

This study extends the data from CCHS 2001 to 2014 to assess the trends of association between occupational injuries and specific occupational variables within the Canadian workforce. Ten years of national survey data were assessed to identify the consistency of these associated trends over the included years of data to determine unchanging outcomes.

METHODS

Survey data collection

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) is a cross-sectional survey that collects information regarding the health status, health-care utilization, and health determinants from a representative sample of the Canadian population. The primary use of the CCHS data is for health surveillance and population health research. From 2001–2005, the survey was conducted every 2 years during 2001, 2003, 2005 reference periods with a target sample of approximately 130,000 respondents. Starting 2007, the CCHS survey was administered annually, and the sample size was changed to 65,000 respondents. The CCHS covers the population aged 12 and over from all ten provinces and three territories of Canada. Persons living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements in the provinces, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, the institutionalized population, and persons living in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James are exclude from the survey. It is important to note that these exclusions represent < 3% of the Canadian population aged 12 and over.[6]

Variables

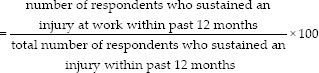

The primary outcome of the study was to determine the prevalence and association of occupational injuries in relation to various occupational health outcomes. For the purpose of this study, CCHS respondents were included based on their age, employment status, and whether they have sustained an injury or not: The CCHS respondents included in our analyses were of age 15–74 years, were employed or self-employed throughout the past year before the survey and had sustained an injury either at or outside of work within the past 12 months. The types of injuries that were included in the CCHS and were considered in this study included: multiple minor injuries; broken/fractured bones; burn, scald, chemical burn; dislocation; sprain or strain (this does not include repetitive strain or sprain); cut, puncture, animal bite; scrape, bruise, blister; concussion or other brain injury; poisoning; injury to internal organs; or other injuries. For individuals, who sustained multiple injuries during different activities, the most serious one out of those multiple injuries is considered. The set of commands for Stata MP version 11 used for the inclusion criteria as stated in the Appendix. The final study sample consisted of employed individuals who had sustained an injury in the past 12 months; this sample was divided into two cohorts based on whether the injury was sustained at work or outside of work. The two groups were subjected to statistical analysis to compare the rate of injuries occurring at work with those occurring outside of work with regards to their association with the occupational outcomes that were included in our analyses. The rate of occupational injuries for the purpose of this study was defined as follows:

The occupational variables included in the study were the type of occupation, the employment status (full time or part time), level of education, the presence of a chronic condition, and the number of injuries sustained. The variables of age and sex were also included to account for any confounding that may result from these variables. Table 1 provides the summary of variables included in the study analyses for each year.

Table 1.

Summary of the variables analyzed for each Canadian Community Health Survey year

| 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of occupation | Y | - | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Full-time/part-time | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Level of education | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Has a chronic condition | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Activity where most serious injury occurred | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Number of injuries | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

A dash represents where data were not available. The CCHS 2008 dataset did not provide any information on the injuries and therefore was not included in our study CCHS: Canadian Community Health Survey

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis was completed in StataMP 11,[7] with “svyset” commands to apply sampling weights and to adjust for clustering of observations within the CCHS and census region and derived from our previous work [Appendix for a representative set of codes].[8]

Variables were filtered using bivariate analysis: Variables with P < 0.1 were kept for model building, and the rest were dropped (e.g., chronic condition). The statistical significance level of P < 0.1 was used to ensure that all the potentially useful variables were retained for the analysis. Backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to create[8] three models of demographics and health factors associated with injuries at the workplace in Canada: (1) type of occupation, (2) full time/part-time employment status and the number of injuries, and (3) level of education. A statistical significance level of P < 0.05 was used in each of the final analyses. A representative set of commands used to perform the statistical analysis of the 2001 CCHS dataset is included below.

RESULTS

Study sample selection and characteristics

Respondents who fulfilled the following requirement for each survey year were included: aged between 15 and 74 years, a work status of being employed or self-employed for the past 12 months and had sustained an injury in the past 12 months. The final sample size for each year and the representative population size for the sample has been reported in Tables 2 and 3 provides a summary of the study sample characteristics for each CCHS. Table 4 provides the summary of associations between the rate of occupational injuries and various occupational outcomes as based on backward, stepwise logistic regression. Data are provided as odds ratios (OR) at 95% confidence intervals. ORs represent the odds that an outcome, i.e., occupational injury will occur given a particular condition, i.e., the various occupational outcomes being studied. An OR > 1 represents the higher odds of occupational injury given the specific condition.[3]

Table 2.

Survey sample size and representative population size for each Canadian Community Health Survey year

| Total survey sample size | Total representative population size | Study sample size | Representative study population size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 130,880 | 25,722,531 | 11,941 | 2,461,766 |

| 2003 | 42,592 | 8,205,759 | 3059 | 666,454 |

| 2005 | 132,221 | 27,126,165 | 10,006 | 2,315,588 |

| 2007 | 131,061 | 28,017,372 | 1560 | 388,659 |

| 2009 | 124,188 | 28,725,105 | 9986 | 2,603,701 |

| 2010 | 62,909 | 28,878,418 | 5043 | 2,628,394 |

| 2011 | 124,929 | 29,335,211 | 9941 | 2,594,665 |

| 2012 | 61,707 | 29,491,030 | 611 | 405,485 |

| 2013 | 127,462 | 30,002,817 | 10,255 | 2,942,391 |

| 2014 | 63,522 | 30,154,392 | 5137 | 2,940,915 |

Table 3.

Study sample characteristic (%), Canadian Community Health Survey 2001-2014 survey of employed respondents aged 15-74, who had sustained an injury within past 12 months

| 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 62.3 | 63.6 | 62.7 | 59.5 | 59.9 | 59.5 | 62.9 | 63.1 | 58.7 | 58.3 |

| Females | 37.7 | 36.4 | 37.4 | 40.5 | 40.0 | 40.5 | 37.0 | 36.9 | 41.3 | 41.7 |

| Injured at work | 32.1 | 31.3 | 25.1 | 24.8 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 21.1 | 20.6 | 18. 9 | 19.1 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 15-19 | 14.25 | 13.86 | 11.69 | 9.86 | 10.56 | 10.32 | 8.83 | 9.35 | 8.52 | 8.86 |

| 20-29 | 26.01 | 26.65 | 25.04 | 25.24 | 24.86 | 25.61 | 31.22 | 28.61 | 25.83 | 25.89 |

| 30-39 | 23.38 | 19.13 | 21.10 | 20.03 | 18.85 | 18.07 | 21.97 | 20.87 | 20.78 | 20.30 |

| 40-49 | 22.29 | 23.37 | 24.04 | 24.14 | 21.89 | 21.83 | 18.34 | 21.67 | 19.38 | 18.47 |

| 50-59 | 10.92 | 13.33 | 14.35 | 16.33 | 18.22 | 18.65 | 14.98 | 14.74 | 18.29 | 18.42 |

| 60-69 | 2.82 | 3.36 | 3.50 | 4.16 | 5.21 | 5.01 | 4.42 | 4.56 | 6.77 | 7.71 |

| 70-74 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| With chronic condition | 66.25 | 65.58 | 72.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Type of occupation | ||||||||||

| Management, sciences, health, education, arts, culture | 30.85 | - | - | 33.39 | 34.98 | 33.39 | 31.88 | 33.74 | 35.35 | 35.06 |

| Business, finance, administration | 8.8 | - | - | 15.5 | 16.52 | 16.98 | 14.16 | 12.35 | 16.34 | 15.96 |

| Sales or service | 24.74 | - | - | 23.71 | 24.71 | 25.87 | 22.67 | 21.35 | 23.92 | 23.58 |

| Trades, transport or equipment operator | 17.94 | - | - | 21.61 | 16.71 | 16.6 | 23.20 | 22.71 | 16.37 | 16.09 |

| Primary industry, processing, manufacturing, utilities | 10.61 | - | - | 5.79 | 7.08 | 7.16 | 8.11 | 9.86 | 8.02 | 9.31 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Full-time | 80.85 | 79.43 | 82.25 | 80.69 | 80.81 | 80.34 | 83.97 | 85.99 | 81.72 | 80.61 |

| Part-time | 19.15 | 20.57 | 17.75 | 19.31 | 19.19 | 19.66 | 16.03 | 14.01 | 18.28 | 19.39 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Lower than secondary | 20.86 | 18.82 | 13.78 | 13.12 | 10.86 | 10.33 | 10.26 | 9.27 | 8.93 | 9.63 |

| Secondary graduation | 20.38 | 14.57 | 15.71 | 16.44 | 14.68 | 14.97 | 21.17 | 20.07 | 19.48 | 17.23 |

| Other post grade | 10.93 | 9.58 | 11.36 | 12.57 | 11.19 | 11.61 | 4.75 | 4.13 | 6.98 | 6.56 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 47.83 | 57.03 | 59.16 | 57.87 | 63.27 | 63.09 | 63.82 | 66.53 | 64.61 | 66.58 |

Dashes are present where data were not available

Table 4.

Summary of the associations between occupational injuries and occupational health factors based on a backwards, stepwise logistic regression model

| 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of occupation | ||||||||||

| Management, sciences, health, education, arts,culture | 1.0 | - | - | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Business, finance, administration | 0.58** | - | - | - | - | 0.61* | - | - | 0.72* | 0.62* |

| Sales or service | 1.84** | - | - | - | 2.25** | 2.16** | 3.59* | 4.52* | 2.41** | 2.61** |

| Trades, transport or equipment operator | 4.17** | - | - | 5.27** | 4.73** | 4.71** | 4.89** | 6.80** | 4.60** | 4.38** |

| Primary industry, processing, manufacturing,utilities | 4.16** | - | - | 2.84* | 3.66** | 3.64** | 5.05* | 6.36* | 4.48** | 4.41** |

| Number of injuries | ||||||||||

| One injury | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Two injuries | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Three to five injuries | - | - | - | 0.28* | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Six or more injuries | 1.96* | - | 1.65** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Full-time | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Part-time | 0.51** | 0.61* | 0.61** | 0.53* | 0.53** | 0.52** | - | - | - | - |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Secondary school graduation | - | 0.64* | 0.58** | - | 0.59** | - | - | - | - | - |

| Some postsecondary | 0.59** | - | 0.52** | - | 0.41** | 0.41** | 0.38* | - | 0.56* | 0.45* |

| Postsecondary graduation | 0.51** | 0.47* | 0.40** | - | 0.38** | 0.42** | - | - | 0.48** | 0.46** |

*P<0.05, **P<0.001. A dash represents where the data were not available from the CCHS. Figures are OR at 95% CI and P<0.05. A dash represents where the data were not available. OR: Odd ratios, CI: Confidence interval, CCHS: Canadian Community Health Survey

Type of occupation

A significant association (P < 0.05) was observed between the types of occupation and rate of occupational injuries. In total, data on the type of occupation were collected for eight CCHS (2001, 2007, and 2009–2014). Four out of the eight CCHS dataset suggested that there was a negative association between workplace injuries and jobs in business, finance, administration sectors (2001: OR = 0.58, P < 0.05; 2010: OR = 0.61, P = 0.04; 2013: OR = 0.72, P = 0.044; 2014: OR = 0.62, P = 0.041) compared to management, sciences, health, education, arts, and culture. OR <1 suggested the lower odds of injuries occurring in jobs within business, finance, and administration sectors.

Respondents with jobs in the trades, transport or equipment operator were the most likely to have sustained occupational injuries [Table 4]. For CCHS 2001, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, and 2013, the highest odds of workplace injuries were observed for jobs in the trades, transport, or equipment operator sectors (P < 0.001), whereas for CCHS 2011 and 2014, jobs in primary industry, processing, manufacturing, and utilities sectors were associated with the highest odds of occupational injuries.

Number of injuries

A significant, positive association (P < 0.05) was observed between workplace injuries and the number of injuries. Respondents sustaining injuries at work were more likely to sustain six of more injuries for 2001 (OR = 1.96, P = 0.012) and 2005 (OR = 1.65, P < 0.001) cohorts. A negative association between occupational injuries and three to five injuries was observed for 2007 (OR = 0.28, P = 0.02) CCHS. Interestingly, individuals sustaining occupational injuries are at higher odds of sustaining six or more injuries compared to a lesser number of injuries.

Employment status

In six of the 10 CCHS (2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2010), a significant, negative association (P < 0.05) was observed between part-time employment and workplace injuries compared to full-time job (2001: OR = 0.51, P < 0.001; 2003: OR = 0.61, P = 0.024; 2005: OR = 0.61, P < 0.001; 2007: OR = 0.53, P = 0.039; 2009: OR = 0.53, P < 0.001; 2010: OR = 0.52, P < 0.001). This suggests that respondents with full-time jobs were at higher odds of sustaining injuries at work in comparison to part-time workers.

Level of education

In the final multivariate regression analysis, an overall negative association was observed between the rate of occupational injuries and the level of education. Lower OR occupational injuries was observed among people with a higher level of education. Compared to individuals, who acquired less than secondary graduation, individuals with postsecondary graduation were at lower odds of sustaining workplace injuries for years 2001 (OR = 0.51, P < 0.001), 2003 (OR = 0.47, P = 0.001), 2005 (OR = 0.40, P < 0.001), 2009 (OR = 0.38, P < 0.001), 2010 (OR = 0.42, P < 0.001), 2013 (OR = 0.48, P < 0.001), and 2014 (OR = 0.46, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to use CCHS data to look at the association between the rates of occupational injuries and various occupational health outcomes within the Canadian context.

It is well documented in the literature that workers within the trades, processing, and manufacturing and utility industries, are more likely to experience injuries than individuals working in other industries.[9,10] Our study provides further support for these findings and shows that these results have remained consistent over the years. Various reasons that have been provided to explain the higher risk of injuries at jobs within these sectors injuries include routine overtime work, job strain, emotional exhaustion, role conflict, and stress.[11,12,13]

Of particular interest was the positive association between sales and service occupations and occupational injuries. In a previous Canadian study, it was found that in young workers between the 15 and 24 years of age in sales/service and administrative/clerical jobs had the lowest work injury rates compared to other types of jobs.[6] While sales and service occupations still had lower ORs compared to the trades and primary industry categories in our study, it was significantly higher than management and administrative occupations. One factor that may attribute to these results is strain injuries. The relative risk of repetitive strain injuries is higher for sales and service occupations compared to clerical occupations, but still lower than processing and construction occupations.[10] This finding is important as the sales and service industry makes up 27.1% and 18.7% of the Canadian labor force for women and men aged 15 years and over, respectively.[14] Further research is required for the role of policy in decreasing the risks of occupational injuries within the various industries.

While socioeconomic factors such as education and income are well-known determinants of health, less is known about how it affects work-related injuries.[15,16,17] Our study provides support that higher levels of education are associated with lower odds of the work injury. This trend is consistent within and between each year. However, it is still not clear what the underlying mechanisms are that cause higher levels of work injury among those with a level less education. Higher education may provide improved occupational opportunities that require less physical demand and reduced hazardous exposure, thus decreasing the risk for injury.

There is also evidence that occupational “prestige” may also affect an individual's overall health, where occupational prestige represents the perception of a job's social status and is a measure of the social standing of both the job and the worker.[18] One study found that higher occupational prestige was associated with lower odds of self-reported poor health. The mechanism behind how occupational prestige can affect work-related injuries has not been investigated and is an area of potential future studies. Our research provides evidence to support the association between education level and occupational injuries.

The main limitation of this study is the self-reported nature of the questionnaires, which may affect the accuracy of some of the responses. Other limitations of this study are related to the representative nature of the CCHS and do not fully capture all occupational injuries, reported or unreported. This reduces the comprehensiveness of our data set and may present a conservative bias to extrapolations of the results. Despite this, our collective results from CCHS data between 2001 and 2014 suggests that occupational injuries are associated with various factors including the type of occupation, the number of injuries, employment status, and the level of education received. These results may allow policymakers, employers, and other stakeholders to carefully consider and address the impact that occupational injuries have on the Canadian workforce.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

svyset GEOADPMF [pweight=WTSAM], vce (linearized) singleunit (missing)

keep WTSAM LBFA_31A LBFADPFT INJA_01 INJAG02 INJAG09 DHHGAGE DHH_SEX GEOADPMF LBFAG31 EDUADR04 CCCAF1

drop if DHHGAGE < 2

drop if DHHGAGE > 13

drop if LBFAG31 > 2

drop if LBFADPFT > 2

drop if LBFA_31A > 9

drop if INJA_01 > 1

rename INJAG09 Location

recode Location (2=1) (1=0) (3=0) (4=0) (missing=0)

recode LBFA_31A (1=1) (2=1) (3=1) (4=2) (5=3) (6=4) (7=5) (8=5)

svy: tab Location DHH_SEX

svy: tab Location DHHGAGE

svy: tab Location LBFA_31A

svy: tab Location EDUADR04

svy: tab Location CCCAF1

svy: tab Location LBFADPFT

keep WTSAM GEOADPMF DHHGAGE DHH_SEX Location LBFA_31A LBFADPFT INJAG02 EDUADR04

-

xi: svy: logistic Location i.DHHGAGE i.DHH_SEX i.LBFA_31A

- test _ILBFA_31A_2 _ILBFA_31A_3 _ILBFA_31A_4 _ILBFA_31A_5 _ILBFA_31A_9

- test _IDHH_SEX_2

- test _IDHHGAGE_3 _IDHHGAGE_4 _IDHHGAGE_5 _IDHHGAGE_6 _IDHHGAGE_7 _IDHHGAGE_8_IDHHGAGE_9 _IDHHGAGE_10 _IDHHGAGE_11 _IDHHGAGE_12 _IDHHGAGE_13

-

xi: svy: logistic Location i.DHHGAGE i.DHH_SEX i.LBFA_31A i.LBFADPFT i.INJAG02

- test _IINJAG02_2 _IINJAG02_3 _IINJAG02_4

- test _ILBFADPFT_2

xi: svy: logistic Location i.DHHGAGE i.DHH_SEX i.EDUADR04 test _IEDUADR04_2 _IEDUADR04_3_IEDUADR04_4

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of Workers' Compensation Boards of Canada. Injuries/Diseases/Fatalities. [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 01]. Available from: http://www.awcbc.org/?page_id=4040 .

- 2.Creating Safe and Healthy Workplaces for All. ILO. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_305423.pdf .

- 3.Mekkodathil A, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H. Occupational injuries in workers from different ethnicities. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2016;6:25–32. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.177365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Statistics Canada. Work Injuries: Findings. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2006007/article/injuries-blessures/4149017-eng.htm .

- 5.Association of Workers' Compensation Boards of Canada. Injuries/Diseases/Fatalities. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: http://www.awcbc.org/?page_id=4040 .

- 6.Breslin FC, Smith P, Mustard C, Zhao R. Young people and work injuries: An examination of jurisdictional variation within Canada. Inj Prev. 2006;12:105–10. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.009449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.StataCorp LP. Stata statistical software, version 11. StataCorp. College Station (TX) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li AK, Nowrouzi-Kia B. Impact of diabetes mellitus on occupational health outcomes in Canada. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2017;8:96–108. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2017.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alamgir H, Yu S, Drebit S, Fast C, Kidd C. Are female healthcare workers at higher risk of occupational injury? Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:149–52. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashbury FD. Occupational repetitive strain injuries and gender in Ontario, 1986 to 1991. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37:479–85. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199504000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dembe AE, Erickson JB, Delbos RG, Banks SM. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:588–97. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannessen HA, Gravseth HM, Sterud T. Psychosocial factors at work and occupational injuries: A prospective study of the general working population in Norway. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58:561–7. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West C, Fekedulegn D, Andrew M, Burchfiel CM, Harlow S, Bingham CR, et al. On-duty nonfatal injury that lead to work absences among police officers and level of perceived stress. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:1084–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada. Portrait of Canada's Labour Force. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-012-x/99-012-x2011002-eng.cfm .

- 15.Piha K, Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Socio-economic and occupational determinants of work injury absence. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:693–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White CM, St John PD, Cheverie MR, Iraniparast M, Tyas SL. The role of income and occupation in the association of education with healthy aging: Results from a population-based, prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1181. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2504-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujishiro K, Xu J, Gong F. What does “occupation” represent as an indicator of socioeconomic status? Exploring occupational prestige and health. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:2100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]