Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hypoxemia is the most common complication during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults and may increase the risk of cardiac arrest and death. Whether positive-pressure ventilation with a bag-mask device (bag-mask ventilation) during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults prevents hypoxemia without increasing the risk of aspiration remains controversial.

METHODS

In a multicenter, randomized trial conducted in seven intensive care units in the United States, we randomly assigned adults undergoing tracheal intubation to receive either ventilation with a bag-mask device or no ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy. The primary outcome was the lowest oxygen saturation observed during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation. The secondary outcome was the incidence of severe hypoxemia, defined as an oxygen saturation of less than 80%.

RESULTS

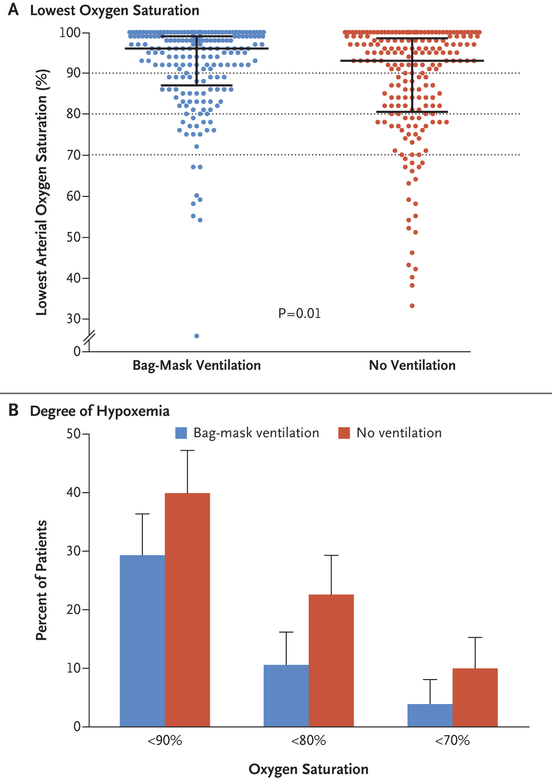

Among the 401 patients enrolled, the median lowest oxygen saturation was 96% (interquartile range, 87 to 99) in the bag-mask ventilation group and 93% (interquartile range, 81 to 99) in the no-ventilation group (P = 0.01). A total of 21 patients (10.9%) in the bag-mask ventilation group had severe hypoxemia, as compared with 45 patients (22.8%) in the no-ventilation group (relative risk, 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.30 to 0.77). Operator-reported aspiration occurred during 2.5% of intubations in the bag-mask ventilation group and during 4.0% in the no-ventilation group (P = 0.41). The incidence of new opacity on chest radiography in the 48 hours after tracheal intubation was 16.4% and 14.8%, respectively (P = 0.73).

CONCLUSIONS

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, patients receiving bag-mask ventilation had higher oxygen saturations and a lower incidence of severe hypoxemia than those receiving no ventilation. (Funded by Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research and others; PreVent ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03026322.)

More than 1.5 million patients undergo tracheal intubation each year in the United States.1 Up to 40% of tracheal intubations in the intensive care unit (ICU) are complicated by hypoxemia, which may lead to cardiac arrest and death.2–7

For critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, the nearly simultaneous administration of a sedative and a neuromuscular blocking agent (rapid-sequence induction) facilitates intubation on the first laryngoscopy attempt.8–10 However, rapid-sequence induction involves an inherent delay of 45 to 90 seconds between medication administration and initiation of laryngoscopy.11 Whether providing positive-pressure ventilation with a bag-mask device (bag-mask ventilation) during this interval prevents hypoxemia without increasing the risk of gastric or oropharyngeal aspiration has been debated for nearly 50 years.12–14 Some guidelines recommend providing bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy to all patients, including those who are not initially hypoxemic.12,15–17 Other guidelines recommend avoiding bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy except to treat hypoxemia, a recommendation that prioritizes the perceived risk of aspiration over the potential benefits of preventing hypoxemia.11,13,18,19

To determine the effect of bag-mask ventilation on hypoxemia during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults, we conducted the Preventing Hypoxemia with Manual Ventilation during Endotracheal Intubation (PreVent) trial. We hypothesized that as compared with no ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy, bag-mask ventilation would significantly increase the lowest oxygen saturation during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation.

METHODS

Trial Design and Oversight

From March 15, 2017, to May 6, 2018, we conducted a multicenter, parallel-group, unblinded, pragmatic, randomized trial comparing bag-mask ventilation with no ventilation during the interval between induction (administration of a sedative medication) and laryngoscopy during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. The trial was approved by either the central institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center or the local institutional review board at each trial site; the requirement for informed consent was waived. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.)

The trial was registered online before initiation and was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. The protocol and statistical analysis plan (also available at NEJM.org) were published before the conclusion of enrollment.20 The authors designed the trial, collected the data, and performed the analyses. The institutions that provided funding to the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research had no role in the conception, design, or conduct of the trial, nor did their representatives participate in the collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript, vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data, and approved the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Trial Sites and Patient Population

The trial was conducted in seven academic ICUs across the United States. (Details regarding the trial sites are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.) Adults (age, ≥18 years) undergoing induction and tracheal intubation in a participating ICU were eligible. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, were incarcerated, or had such an immediate need for tracheal intubation that randomization was precluded or if the treating clinicians had determined that ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy was either required (e.g., as a treatment for hypoxemia or severe acidemia) or contraindicated (e.g., because of an increased risk of aspiration from ongoing emesis, hematemesis, or hemoptysis). Complete lists of inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Randomization

Patients underwent randomization in a 1:1 ratio to undergo either bag-mask ventilation or no ventilation in permuted blocks of 2, 4, and 6, stratified according to trial site. Trial-group assignments were placed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes and remained concealed until after enrollment. Given the nature of the intervention, patients, clinicians, and research personnel were aware of trial-group assignments after randomization.

Trial Interventions

For patients who were assigned to the bag-mask ventilation group, bag-mask ventilation was provided by treating clinicians during the interval from induction until the initiation of laryngos-copy. Structured education regarding best practices in bag-mask ventilation included the use of oxygen flow rates of at least 15 liters per minute, a valve attached to the expiratory port of the bag-mask device to generate a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 to 10 cm of water, an oropharyngeal airway, a two-handed mask seal performed by the intubating clinician with a head-tilt and chin-lift maneuver, and ventilation at 10 breaths per minute with the smallest volume required to generate a visible chest rise.21 Failure to administer bag-mask ventilation at the start of induction was recorded as a protocol violation. (Details regarding bag-mask ventilation practices are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

For patients who were assigned to the no-ventilation group, bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy was not permitted, except after a failed attempt at laryngoscopy, as treatment for hypoxemia (oxygen saturation, <90%), or at any point if the treating clinicians determined that such treatment was necessary for the safety of the patient. Administration of bag-mask ventilation before the first laryngos-copy attempt in the absence of an oxygen saturation of less than 90% was recorded as a protocol violation.

Noninvasive ventilation during the interval between induction and laryngoscopy was not allowed in either trial group because it could confound the provision of bag-mask ventilation. All other aspects of the procedure were deferred to treating clinicians. Specifically, all methods of preoxygenation, including noninvasive ventilation, were allowed in either group before induction. Because a previous trial in a similar setting showed no benefit for the use of supplemental oxygen without ventilation during the interval between induction and tracheal intubation (apneic oxygenation),2 apneic oxygenation was not mandated but was allowed in either group.

Data Collection

A trained nurse or physician who was not involved in the performance of the procedure collected data for periprocedural outcomes, including oxygen saturation and systolic blood pressure at the time of induction, lowest oxygen saturation and lowest systolic blood pressure during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation, and the time from induction to intubation. Immediately after each intubation, the operator reported the Cormack– Lehane grade of glottic view,22 subjective difficulty of tracheal intubation, airway complications during the procedure, and the level of operator experience. Trial personnel collected data regarding baseline characteristics, management before and after laryngoscopy, and clinical outcomes from the medical record.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the lowest oxygen saturation (as measured by continuous pulse oximetry) observed during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation. The single prespecified secondary outcome was the incidence of severe hypoxemia, which was defined as an oxygen saturation of less than 80% during the same interval.

To capture objective clinical manifestations of periprocedural oropharyngeal or gastric aspiration, trial personnel collected measurements of oxygen saturation, fraction of inspired oxygen, and positive end-expiratory pressure, recorded as part of routine care in the 24 hours after intubation. The worst value for each variable between 6 and 24 hours after tracheal intubation was considered to be a main safety outcome.

Additional procedural outcomes included operator-reported oropharyngeal or gastric aspiration and the presence of a new opacity on chest radiography within 48 hours after tracheal intubation. The presence of a new opacity was adjudicated by independent review of chest radiographs by two pulmonary and critical care–medicine attending physicians who were unaware of trial-group assignments and outcomes. (Additional details regarding trial outcomes are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

Statistical Analysis

Details regarding the determination of the sample size have been reported previously.20 Assuming a standard deviation of 14% in the lowest oxygen saturation and less than 5% missing data, we determined that the enrollment of 350 patients would provide a power of 90% at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 to detect an absolute between-group difference of 5 percentage points in the lowest oxygen saturation. As specified in the initial trial protocol, the standard deviation for the lowest oxygen saturation in the control group was examined at the interim analysis. At that time, the data and safety monitoring board recommended increasing the sample size to 400 patients to maintain the 90% statistical power to detect a between-group difference of 5 percentage points in the lowest oxygen saturation. (Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

The primary analysis was an unadjusted, intention-to-treat comparison of the lowest oxygen saturation among patients in the two trial groups with the use of the Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. Sensitivity analyses used alternate definitions of the lowest oxygen saturation, imputed missing data for the lowest oxygen saturation, and evaluated the marginal effect of the trial group on the lowest oxygen saturation after accounting for prespecified confounders23 and correlation of measurements within each trial unit with the use of generalized estimating equations. Linear regression models were fit to assess for a possible effect modification by baseline variables. (Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

In a per-protocol analysis, patients who had received bag-mask ventilation to prevent hypoxemia before the first attempt at laryngoscopy were compared with patients who had not received bag-mask ventilation. Patients who had received bag-mask ventilation after a failed attempt at laryngoscopy or as treatment for hypoxemia were assessed with their assigned group.

After the enrollment of 175 patients, the data and safety monitoring board conducted a single interim analysis comparing the lowest oxygen saturation between groups using a Haybittle– Peto stopping boundary for efficacy of P<0.001. For the final analysis of the primary outcome, a two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes are reported with the use of point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. The widths of the confidence intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive differences in treatment effects between groups. All analyses were performed with the use of Stata software, version 15.1 (StataCorp), or statistical software R, version 3.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

PATIENTS

Of the 667 screened patients who met the inclusion criteria, 401 (60.1%) met no exclusion criteria and were enrolled (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The median age was 60 years; nearly 50% of patients had sepsis or septic shock, and nearly 60% had hypoxemic respiratory failure as an indication for tracheal intubation. A total of 199 patients were assigned to undergo bag-mask ventilation, and 202 were assigned to undergo no ventilation (Table 1, and Tables S1 through S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Bag-Mask Ventilation (N = 199) |

No Ventilation (N=202) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 59 (45–67) | 60 (48–68) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 118 (59.3) | 108 (53.5) |

| White race — no. (%)† | 141 (70.9) | 134 (66.3) |

| Median body-mass index (IQR)‡ | 27.1 (22.7–32.3) | 27.6 (23.4–34.2) |

| Median APACHE II score (IQR)§ | 22 (16–29) | 22 (16–28) |

| Receipt of vasopressor — no. (%) | 35 (17.6) | 40 (19.8) |

| Active medical conditions — no. (%)¶ | ||

| Sepsis or septic shock | 98 (49.2) | 97 (48.0) |

| Pneumonia | 57 (28.6) | 80 (39.6) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 22 (11.1) | 21 (10.4) |

| Aspiration | 14 (7.0) | 12 (5.9) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 31 (15.6) | 18 (8.9) |

| Altered mental status | 92 (46.2) | 82 (40.6) |

| Indication for intubation — no. (%)¶ | ||

| Hypoxemic respiratory failure | 117 (58.8) | 116 (57.4) |

| Hypercarbic respiratory failure | 39 (19.6) | 55 (27.2) |

| Airway protection for decreased level of consciousness | 74 (37.2) | 76 (37.6) |

| Before procedure | 21 (10.6) | 13 (6.4) |

| One or more difficult airway characteristics — no. (%)‖ | 95 (47.7) | 102 (50.5) |

| One or more risk factors for aspiration — no. (%)** | 123 (61.8) | 117(57.9) |

| Bilevel positive airway pressure in previous 6 hr — no. (%) | 44 (22.1) | 57 (28.2) |

| Median highest fraction of inspired oxygen in previous 6 hr (IQR) | 0.4 (0.3–1.0) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) |

| Median lowest oxygen saturation in previous 6 hr (IQR) — % | 91 (87–95) | 92 (88–95) |

| Median lowest ratio of oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen in previous 6 hr (IQR) | 202 (94–303) | 189 (97–294) |

The only significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two trial groups were the proportion of patients with pneumonia (P = 0.02) and gastrointestinal bleeding (P = 0.04). IQR denotes interquartile range.

Race was reported by patients or their surrogates and recorded in the electronic health record as a part of routine clinical care.

At enrollment, data on body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) were missing for five patients (1.2%): three in the bag-mask ventilation group and two in the no-ventilation group.

Scores on the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II range from 0 to 71, with higher scores indicating a greater severity of illness.

Patients could have more than one condition or indication.

Difficult airway characteristics included a body-mass index of more than 30, obstructive sleep apnea, upper gastro intestinal bleeding, limited mouth opening, limited neck mobility, active vomiting or witnessed aspiration, airway mass or infection, epistaxis or oral bleeding, and head or neck radiation.

Risk factors for aspiration included narcotic use, functional or mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction, previous esophageal surgery, head injury, active emesis, active upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

MANAGEMENT BETWEEN ENROLLMENT AND INDUCTION

Preoxygenation with the use of a bag-mask device before induction was more common among patients in the bag-mask ventilation group than among those in the no-ventilation group (39.7% vs. 10.9%; relative risk, 3.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.37 to 5.60) (Table 2, and Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). Conversely, pre-oxygenation with a noninvasive ventilator or high-flow nasal cannula was less common among patients in the bag-mask ventilation group than among those in the no-ventilation group (27.6% vs. 44.1%; relative risk, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.82). The oxygen saturation at the time of induction did not significantly differ between groups (Table 2, and Tables S6 and S7 and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). All the patients received an induction medication, and 97.5% of the patients in each group received a neuromuscular blocking agent; the choice or dose of medication did not differ significantly between groups (Table S8 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Intubation Procedure.

| Characteristic | Bag-Mask Ventilation (N = 199) |

No Ventilation (N = 202) |

Relative Risk or Mean Difference (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before induction | |||

| Preoxygenation method — no. (%)* | |||

| Bag-mask device | 79 (39.7) | 22 (10.9) | 3.65 (2.37 to 5.60) |

| Bilevel positive airway pressure† | 32 (16.1) | 48 (23.8) | 0.68 (0.45 to 1.01) |

| High-flow nasal cannula‡ | 23 (11.6) | 41 (20.3) | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.91) |

| Non-rebreather mask | 54 (27.1) | 62 (30.7) | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.20) |

| Standard nasal cannula‡ | 17 (8.5) | 24 (11.9) | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.30) |

| No preoxygenation | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.5) | 0.44 (0.11 to 1.66) |

| Preoxygenation with positive pressure — no. (%)§ | 132 (66.3) | 111 (55.0) | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.42) |

| Oxygen saturation at induction¶ | |||

| Median (IQR) — % | 99 (95–100) | 99 (96–100) | −0.6 (−1.4 to 0.3)‖ |

| <92% — no./total no. (%) | 27/194 (13.9) | 17/198 (8.6) | 1.62 (0.91 to 2.88) |

| Median systolic blood pressure at induction (IQR) — mm Hg | 122 (105–142) | 123 (107–140) | 0.0 (−5.5 to 5.6)‖ |

| New vasopressor before induction — no./total no. (%) | 27/197 (13.7) | 29/200 (14.5) | 0.95 (0.58 to 1.54) |

| Oxygenation and ventilation between induction and intubation | |||

| Bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy to prevent hypoxemia — no. (%)** |

198 (99.5) | 5 (2.5) | 40.20 (16.91 to 95.53) |

| Bag-mask ventilation between induction and intubation for any indication — no. (%)†† |

198 (99.5) | 44 (21.8) | 4.57 (3.52 to 5.93) |

| Supplemental oxygen between induction and laryngoscopy — no.(%)‡‡ |

199 (100) | 157 (77.7) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.39) |

| After induction§§ | |||

| Median time from induction to laryngoscopy (IQR) — sec | 98 (65–135) | 72 (52–120) | 13.8 (−1.1 to 28.6)‖ |

| Median time from laryngoscopy to intubation (IQR) — sec | 42 (25–72) | 45 (30–71) | −11.5 (−30.5 to 7.5)‖ |

| Median time from induction to intubation (IQR) — sec | 158 (110–218) | 130 (90–191) | 7.7 (−15.6 to 31.0)‖ |

| Video laryngoscope as initial device — no. (%) | 71 (35.7) | 65 (32.2) | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.46) |

| Successful intubation on first attempt — no. (%) | 167 (83.9) | 162 (80.2) | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.15) |

| Use of bougie — no. (%) | 33 (16.6) | 44 (21.8) | 0.76 (0.51 to 1.14) |

More than one method could be used in each patient.

In patients receiving bilevel positive airway pressure, inspiratory and expiratory settings were determined by the operator.

Among the patients with high-flow nasal cannula, flow rates were up to 70 liters per minute of humidified oxygen. Among those with standard nasal cannula, flow rates were 6 liters per minute or less of nonhumidified oxygen.

Preoxygenation with positive pressure was defined as the use of a bag-mask device, bilevel positive airway pressure, or high-flow nasal cannula.

Additional details regarding oxygen saturation at induction are provided in Table S7 and Figure S2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

The mean difference is indicated in this category.

The receipt of bag-mask ventilation by five patients in the no-ventilation group was considered to be a protocol violation. Additional details on protocol violations are provided in Table S9 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Therapeutic bag-mask ventilation was allowed in the no-ventilation group after a failed attempt at laryngoscopy or in patients with an oxygen saturation of less than 90%.

Supplemental oxygen in the bag-mask group was provided by means of bag-mask ventilation. Supplemental oxygen in the no-ventilation group was provided by means of a non-rebreather mask or a nasal cannula. Details are provided in Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Data regarding the time from induction to laryngoscopy were missing for 15 patients (3.7%): 8 in the bag-mask ventilation group and 7 in the no-ventilation group; from laryngoscopy to intubation for 11 patients (2.7%): 7 in the bag-mask ventilation group and 4 in the no-ventilation group; and from induction to intubation for 9 patients (2.2%): 6 in the bag-mask ventilation group and 3 in the no-ventilation group.

MANAGEMENT BETWEEN INDUCTION AND INTUBATION

A total of 198 patients (99.5%) in the bag-mask ventilation group received bag-mask ventilation to prevent hypoxemia before the first attempt at laryngoscopy, as compared with 5 patients (2.5%) in the no-ventilation group (Table 2, and Table S9 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The time from induction to laryngoscopy during which bag-mask ventilation could be provided was 98 seconds (interquartile range, 65 to 135) in the bag-mask ventilation group and 72 seconds (interquartile range, 52 to 120) in the no-ventilation group (mean difference, 13.8 seconds; 95% CI, −1.1 to 28.6) (Table 2, and Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix). Among the patients who received bag-mask ventilation (198 in the ventilation group and 44 in the no-ventilation group), the percentage of patients in whom an oropharyngeal airway was used (39.4% vs. 47.7%; relative risk, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.18) and the percentage in whom a head-tilt and chin-lift or jaw-thrust maneuver was used (83.3% vs. 88.6%; relative risk, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.06) were similar (Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix).

A total of 157 patients (77.7%) in the no-ventilation group received supplemental oxygen between induction and laryngoscopy, primarily through a non-rebreather mask or a nasal cannula (Table 2, and Table S10 in the Supplementary Appendix). Additional characteristics of the tracheal intubation procedure are presented in Table 2, and in Table S11 in the Supplementary Appendix.

PRIMARY OUTCOME

The median lowest oxygen saturation was 96% (interquartile range, 87 to 99) in the bag-mask ventilation group and 93% (interquartile range, 81 to 99) in the no-ventilation group (P = 0.01) (Fig. 1A). The mean difference in the lowest oxygen saturation between the bag-mask ventilation group and the no-ventilation group was 4.7 percentage points (95% CI, 2.5 to 6.8) after adjustment for prespecified covariates and within-unit correlation with the use of multivariable generalized estimating equations (Table S12 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Lowest Oxygen Saturation.

Panel A shows the primary outcome of the lowest oxygen saturation (as measured by continuous pulse oximetry) observed during the interval between induction and 2 minutes after tracheal intubation in patients in the bag-mask ventilation group (blue) and the no-ventilation group (red). The widest horizontal bars represent median values, and the I bars represent the interquartile ranges. The dotted lines represent the thresholds for hypoxemia, severe hypoxemia, and very severe hypoxemia. Panel B shows the percentage of patients who had various degrees of hypoxemia in each group. The T bars represent the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval for the event rate.

In a post hoc analysis that was performed after adjustment for the provision of preoxygenation, for the preoxygenation device, and for the presence of pneumonia or gastrointestinal bleeding, the mean between-group difference in the lowest oxygen saturation was 5.2 percentage points (95% CI, 2.8 to 7.5) (Table S12 in the Supplementary Appendix). Results were similar in the per-protocol analysis and all sensitivity analyses (Table S13 in the Supplementary Appendix).

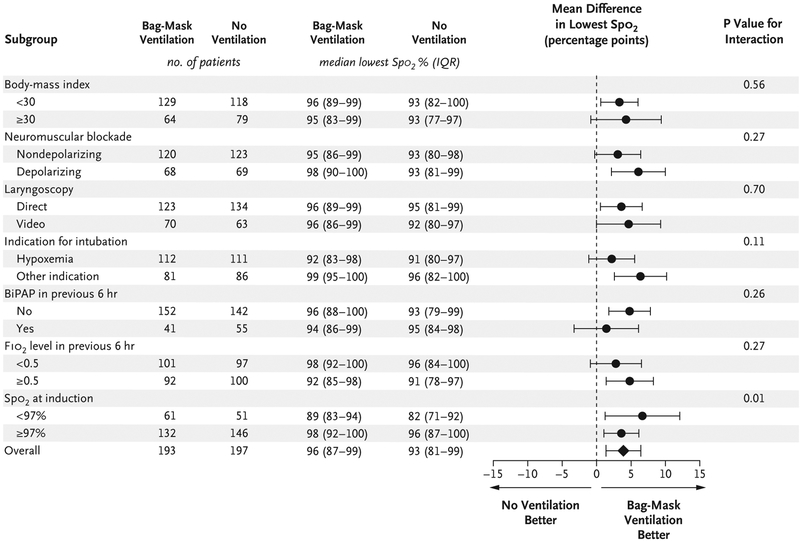

In prespecified subgroup analyses, the difference in the lowest oxygen saturation between the bag-mask ventilation group and the no-ventilation group was greater for patients with lower oxygen saturation at induction (P = 0.01 for interaction) (Fig. 2, and Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). None of the other prespecified characteristics, including body-mass index, score on the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, and operator experience, appeared to modify the effect of bag-mask ventilation on the lowest oxygen saturation (Fig. 2, and Figs. S3 through S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome.

Shown is the unadjusted mean difference in the lowest oxygen saturation between patients undergoing bag-mask ventilation and those not undergoing ventilation in prespecified subgroups. The horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals around the mean difference. The number of patients in each group for whom a measure of the lowest oxygen saturation was available is shown. Five patients in each group did not receive a neuromuscular blocking agent. The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. BiPAP denotes bilevel positive airway pressure, FIO2 highest fraction of inspired oxygen, and Spo2 oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry.

SECONDARY OUTCOME

A total of 21 patients (10.9%) in the bag-mask ventilation group had an oxygen saturation of less than 80%, as compared with 45 patients (22.8%) in the no-ventilation group (relative risk, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.77) (Table 3 and Fig. 1B, and Table S14 and Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3.

Outcomes of Tracheal Intubation.

| Outcome | Bag-Mask Ventilation (N = 199) |

No Ventilation (N = 202) |

Relative Risk or Mean Difference (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary: median lowest oxygen saturation (IQR) — %* | 96 (87–99) | 93 (81–99) | 3.9 (1.4 to 6.5)† |

| Secondary: lowest oxygen saturation of <80% — no./total no. (%) | 21/193 (10.9) | 45/197 (22.8) | 0.48 (0.30 to 0.77) |

| Exploratory oxygen-saturation outcomes | |||

| Lowest oxygen saturation of <90% — no./total no. (%) | 57/193 (29.5) | 79/197 (40.1) | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.97) |

| Lowest oxygen saturation of <70% — no./total no. (%)‡ | 8/193 (4.1) | 20/197 (10.2) | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.90) |

| Median decrease in oxygen saturation (IQR) — percentage points | 1 (0–7) | 5 (0–14) | −4.5 (−6.8 to−2.2)† |

| Exploratory safety outcomes | |||

| Operator-reported aspiration — no. (%) | 5 (2.5) | 8 (4.0) | 0.63 (0.21 to 1.91) |

| New opacity on chest radiography — no./total no. (%) | 31/189 (16.4) | 29/196 (14.8) | 1.11 (0.70 to 1.77) |

| New pneumothorax — no./total no. (%) | 2/189 (1.1) | 6/196 (3.1) | 0.34 (0.07 to 1.66) |

| New vasopressor after induction — no./total no. (%) | 39/196 (19.9) | 46/199 (23.1) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.26) |

| New systolic blood pressure of<65 mm Hg — no./total no. (%) | 8/195 (4.1) | 17/197 (8.6) | 0.48 (0.21 to 1.08) |

| Cardiac arrest within 1 hr after intubation — no. (%) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0.51 (0.09 to 2.74) |

| Exploratory clinical outcomes | |||

| Median no. of ventilator-free days (IQR) | 19 (0–25) | 18 (0–25) | 0.6 (−1.7 to 2.9)† |

| Median no. of days outside intensive care unit (IQR) | 16 (0–22) | 14 (0–22) | 0.8 (−1.3 to 2.9)† |

| Death before hospital discharge — no. (%) | 71 (35.7) | 72 (35.6) | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) |

Data regarding the lowest oxygen saturation were missing for 11 patients (2.7%): 6 in the bag-mask ventilation group and 5 in the no-ventilation group. In the primary analysis comparing lowest oxygen saturation between groups with the use of a Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, the lowest oxygen saturation was higher in the bag-mask ventilation group than in the no-ventilation group (P = 0.01).

The mean difference is indicated in this category.

This outcome was added post hoc.

ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES

A lower percentage of patients in the bag-mask ventilation group than in the no-ventilation group had an oxygen saturation of less than 90% (29.5% vs. 40.1%; relative risk, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.97) or an oxygen saturation of less than 70% (4.1% vs. 10.2%; relative risk, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.90) (Table 3). The median decrease in oxygen saturation from induction to the lowest oxygen saturation was 1 percentage point (inter-quartile range, 0 to 7) in the bag-mask ventilation group and 5 percentage points (interquartile range, 0 to 14) in the no-ventilation group (mean difference, 4.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 2.2 to 6.8).

The bag-mask ventilation group and the no-ventilation group did not significantly differ with regard to the incidence of operator-reported aspiration (2.5% vs. 4.0%; absolute risk difference, −1.5 percentage points; 95% CI, −4.9 to 2.0; P = 0.41) or the presence of a new opacity on chest radiography in the 48 hours after tracheal intubation (16.4% vs. 14.8%; absolute risk difference, 1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, −5.6 to 8.9; P = 0.73) (Table S15 in the Supplementary Appendix).

In addition, there was no significant between-group difference in oxygen saturation, fraction of inspired oxygen, and positive end-expiratory pressure in the 24 hours after tracheal intubation (Table S16 in the Supplementary Appendix), nor in in-hospital mortality and in the number of ventilator-free days or days out of the ICU (Table 3, and Table S14 in the Supplementary Appendix). Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes were similar after adjustment for within-ICU correlation with the use of generalized estimating equations (Tables S6 and S14 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter, randomized trial, the lowest oxygen saturation during tracheal intubation was 3.9 percentage points higher among patients assigned to receive bag-mask ventilation than among those assigned to receive no ventilation from induction to laryngoscopy. At the same time, the absolute percentage of patients who had severe hypoxemia was 12 percentage points lower in the bag-mask ventilation group. These results suggest that for every nine critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, providing bag-mask ventilation between induction and laryngoscopy would prevent severe hypoxemia in one patient.

These findings are important because oxygen saturation is an established end point in airway-management trials2,3,24–26 and is a contributing factor to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death.27,28 The benefit of bag-mask ventilation with regard to oxygen saturation was similar across multiple sensitivity analyses, and the point estimate for lowest oxygen saturation favored bag-mask ventilation in every subgroup.

It has been hypothesized that bag-mask ventilation increases the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation.11,12,29,30 However, previous studies that have evaluated aspiration during bag-mask ventilation have been limited to the examination of anesthetized healthy volunteers, have used epigastric auscultation to detect gastric insufflation as a surrogate for aspiration, and have reported conflicting results.14,31–36 Given the low incidence of operator-reported aspiration during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults,7,37,38 determining whether bag-mask ventilation increases the relative risk of aspiration by 50% would require a trial enrolling approximately 4000 patients. However, our trial provides some reassurance, since the incidence of operator-reported aspiration was numerically lower in the bag-mask ventilation group than in the no-ventilation group. Our results suggest that the effect of bag-mask ventilation on the incidence of aspiration lies between an absolute decrease of 4.9 percentage points and an absolute increase of 2.0 percentage points. A total of 49 otherwise eligible patients (7.3%) were excluded from our trial because clinicians thought they were at very high risk for aspiration, and our results do not inform the safety or effectiveness of bag-mask ventilation in such patients.

Our trial has several strengths. The trial design included randomization to balance baseline confounders, concealment of group assignment until enrollment to prevent selection bias, the conduct of the trial at multiple centers to increase generalizability, and the collection of trial end points by an independent observer to minimize observer bias. Rates of protocol noncompliance and missing data were low.

Our trial also has several limitations. The nature of the trial intervention did not allow blinding, and knowledge of group assignment may have contributed to differences in preoxygenation technique between groups. However, oxygen saturation at induction was numerically lower in the bag-mask ventilation group, and post hoc analyses accounting for preoxygenation methods did not alter the findings that bag-mask ventilation improved oxygen saturation and prevented severe hypoxemia. Furthermore, our trial did not examine the use of noninvasive ventilation during the interval between induction and laryngoscopy and does not inform the choice between noninvasive ventilation and bag-mask ventilation. Because our trial involved only patients in ICUs, it is unclear whether these results can be generalized to patients undergoing tracheal intubation in the emergency department or in a prehospital setting. Whether the effect of bag-mask ventilation on hypoxemia during tracheal intubation translates into differences in other patient-centered outcomes also remains unknown.

In conclusion, in this multicenter, randomized trial involving critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, patients receiving bag-mask ventilation during the interval between induction and laryngoscopy had higher oxygen saturations and lower rates of severe hypoxemia than those receiving no ventilation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (UL1 TR000445 and UL1TR002243) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), to the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. Dr. Casey was supported, in part, by a grant (2T32HL087738–12) from the NIH; Dr. Semler, by grants (K12HL133117 and K23HL143053) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); Dr. Russell, by a grant (T32HL105346–07) from the NHLBI; and Dr. Rice, by a grant (R34HL105869) from the NIH.

Dr. Self reports receiving advisory board fees from Cempra Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Biotest, and Merck and travel support from Gilead Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer; and Dr. Rice, receiving consulting fees and fees for serving as director of medical affairs from Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, consulting fees from Avisa Pharma, and fees for serving as chair of a data and safety monitoring board from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Footnotes

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most frequent procedures performed in U.S. hospitals, 2011: statistical brief #165 In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) statistical briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174682/). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semler MW, Janz DR, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized trial of apneic oxygenation during endotracheal intubation of the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193: 273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semler MW, Janz DR, Russell DW, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of ramped position vs sniffing position during endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Chest 2017; 152: 712–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janz DR, Semler MW, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized trial of video laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 1980–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janz DR, Semler MW, Joffe AM, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of a checklist for endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Chest 2018; 153: 816–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson GD, Ross MJ, McKeown DW, Ray DC. Tracheal intubation in the critically ill: a multi-centre national study of practice and complications. Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 792–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin LD, Mhyre JM, Shanks AM, Tremper KK, Kheterpal S. 3,423 Emergency tracheal intubations at a university hospital: airway outcomes and complications. Anesthesiology 2011; 114: 42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown CA III, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, Walls RM. Techniques, success, and adverse events of emergency department adult intubations. Ann Emerg Med 2015; 65(4): 363–370.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Murphy-Lavoie H, Bugas C, Martinez J, Preston C. Complications of emergency intubation with and without paralysis. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17: 141–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant J-Y, et al. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 2355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CA III, ed. The Walls manual of emergency airway management. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Orbany M, Connolly LA. Rapid sequence induction and intubation: current controversy. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 1318–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stept WJ, Safar P. Rapid induction-intubation for prevention of gastric-content aspiration. Anesth Analg 1970; 49: 633–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salem MR, Clark-Wronski J, Khorasani A, Crystal GJ. Which is the original and which is the modified rapid sequence induction and intubation? Let history be the judge! Anesth Analg 2013; 116: 264–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz DE, Matthay MA, Cohen NH. Death and other complications of emergency airway management in critically ill adults: a prospective investigation of 297 tracheal intubations. Anesthesiology 1995; 82: 367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myatra SN, Ahmed SM, Kundra P, et al. The All India Difficult Airway Association 2016 guidelines for tracheal intubation in the Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Anaesth 2016; 60: 922–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, et al. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120: 323–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem MR. Anesthetic management of patients with “a full stomach”: a critical review. Anesth Analg 1970; 49: 47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stollings JL, Diedrich DA, Oyen LJ, Brown DR. Rapid-sequence intubation: a review of the process and considerations when choosing medications. Ann Pharmacother 2014; 48: 62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey JD, Janz DR, Russell DW, et al. Manual ventilation to prevent hypoxaemia during endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults: protocol and statistical analysis plan for a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ Open 2018; 8(8): e022139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinman ME, Brennan EE, Goldberger ZD, et al. Adult basic life support and cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2015; 132: Suppl 2: S414–S435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 1984; 39: 1105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKown AC, Casey JD, Russell DW, et al. Risk factors for and prediction of hypoxemia during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 1320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baillard C, Fosse J-P, Sebbane M, et al. Noninvasive ventilation improves preoxygenation before intubation of hypoxic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miguel-Montanes R, Hajage D, Messika J, et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy to prevent desaturation during tracheal intubation of intensive care patients with mild-to-moderate hypoxemia. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 574–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vourc’h M, Asfar P, Volteau C, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen during endotracheal intubation in hypoxemic patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41: 1538–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mort TC. The incidence and risk factors for cardiac arrest during emergency tracheal intubation: a justification for incorporating the ASA Guidelines in the remote location. J Clin Anesth 2004; 16: 508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Jong A, Rolle A, Molinari N, et al. Cardiac arrest and mortality related to intubation procedure in critically ill adult patients: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adnet F, Borron SW, Lapostolle F. The safety of rapid sequence induction. Anesthesiology 2002; 96: 517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakles JC. Maintenance of oxygenation during rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2017; 24: 1395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruben H, Knudsen EJ, Carugati G. Gastric inflation in relation to airway pressure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1961; 5: 107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Mullane EJ. Vomiting and regurgitation during anaesthesia. Lancet 1954; 266: 1209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Goedecke A, Wenzel V, Hörmann C, et al. Effects of face mask ventilation in apneic patients with a resuscitation ventilator in comparison with a bag-valve-mask. J Emerg Med 2006; 30: 63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouvet L, Albert M-L, Augris C, et al. Real-time detection of gastric insufflation related to facemask pressure-controlled ventilation using ultrasonography of the antrum and epigastric auscultation in non-paralyzed patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiler N, Heinrichs W, Dick W. Assessment of pulmonary mechanics and gastric inflation pressure during mask ventilation. Prehosp Disaster Med 1995; 10: 101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens JH. Anaesthetic problems of intestinal obstruction in adults. Br J Anaesth 1964; 36: 438–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driver BE, Klein LR, Schick AL, Prekker ME, Reardon RF, Miner JR. The occurrence of aspiration pneumonia after emergency endotracheal intubation. Am J Emerg Med 2018; 36: 193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellin-Olsen J, Fasting S, Gisvold SE. Routine preoperative gastric emptying is seldom indicated: a study of 85,594 anaesthetics with special focus on aspiration pneumonia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 1184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.