Abstract

The corrosion inhibition performance of Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2 diol) cyclotriphosphazene (HMC) on carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution was investigated by weight loss (WL), potentiodynamic polarization (PDP), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements, Density functional theory (DFT) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation. The corrosion inhibition efficiency at optimum concentration (10−3M) is 99% of HMC at 298 K. The corrosion inhibition efficiency at 10−3 M decreases with increase in temperature. The adsorption of HMC on the surface of carbon steel obeyed Langmuir isotherm. Potentiodynamic polarization study confirmed that inhibitor anodic-type. DFT and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations based computational approaches were under taken to support the experimental findings. DFT studies revealed that HMC interact with metallic surface through donor-acceptor interactions in which the anionic parts act as electron donor (HOMO) and cationic parts behaved as electron acceptor (LUMO). The MC simulations study showed that studied HMC adsorb spontaneously on Fe (110) surface.

Keywords: Materials chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Inorganic chemistry

1. Introduction

Steel alloys are widely utilized in many applications including petroleum industries, especially carbon steel are prone to corrosion when they come into contact with corrosive materials, especially in an environment containing Cl− ions. Presence of Cl− ion on the metallic surface initiates the formation of metal oxides; thereby adversely affect the physiochemical properties of the metals. The use of corrosion inhibitors, mainly heterocyclic compounds have been reported to be one of the most effective methods for against corrosion because they can easily adsorb on metallic surface via their molecular structures P, O, S, N, π-electrons and aromatic rings [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Many of these heterocyclic compounds are obtained efficiently using easy-access synthesis pathways and are usually used at lower concentrations during the corrosion inhibition process [6, 7, 8]. Among this group of heterocyclic compounds, we find Hexachlorocyclotriphosphazene. Hexachlorocyclotriphosphazene are an important group containing the formula (NPCl2)3. The molecule has a cyclic backbone consisting of alternating P and N atoms. They have active phosphorus-halogen bonds that can be replaced with nucleophiles, leading to the formation of different types of product [9, 10, 11]. Cyclotriphosphazene is well established nitrogen rich ring containing molecule with three additional nitrogen atoms those can easily protonate and enhance the solubility of polar solvents. Recently, derivatization of cyclotriphosphazene gained the significant advanced for variety of purposes including corrosion inhibition. Cyclotriphosphazene have been investigated as effective corrosion inhibitors for metals and alloys in aggressive solutions owing to their high protection ability which is in turn attributed to the adsorption of these compounds by their non-bonding electrons of nitrogen atoms and π-electrons of three double (-P=N-) bonds. In this study demonstrated the effect of cyclotriphosphazene derivative designated as Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2-diol) cyclotriphosphazene (HMC) having either six identical oxygen containing 3-methoxy propan-1,2 diols. Last decade has witnessed a dramatic increase of using Density Functional Theory methods (DFT) to magnificently define the chemical reactivity of inhibitors and their adsorption competence on metal surface [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. Such computations have been widely used to analyze the molecular electronic structures of adsorption-type inhibitors using a number of quantum chemical descriptors which gives important insights on corrosion inhibition mechanisms. Coupled with the fact that metal inhibitor interactions can be best describe with the aid of the Hard and Soft Acid and Bases (HSAB) principle [19], where organic inhibitors can be regarded as Lewis bases that offer unshared non-bonding and π-electrons to the empty d-orbitals of the iron atoms that acted as electron acceptor (Lewis acid). Therefore, inhibition behavior of the organic inhibitors including HMC is largely influenced by the electronic properties of the inhibitor molecules. Monte Carlo (MC) simulation has been another effective tool to study the interaction of inhibitors with the metal surface or similar problems.

In view of this, present investigation deals with the implementation of one cyclotriphosphazene derivatives synthesized by condensation of Hexachlorocyclotriphosphazene and 2,3-epoxy-1-propanol and demonstrated as corrosion inhibitor for marine-environment (3% NaCl) corrosion of carbon steel. Several commonly employed methods such as chemical (weight loss), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) have been undertaken to study the inhibition ability of the Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2-diol) cyclotriphosphazene (HMC). The adsorption and inhibition behavior of HMC were supported by density functional theory (DFT) based quantum chemical calculations method. A significant correlation among the parameters of experimental and theoretical methods has been achieved in present study. The most stable configuration and adsorption energies for the interaction of the inhibitor with Fe (110) surface were studied by Monte Carlo simulation.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

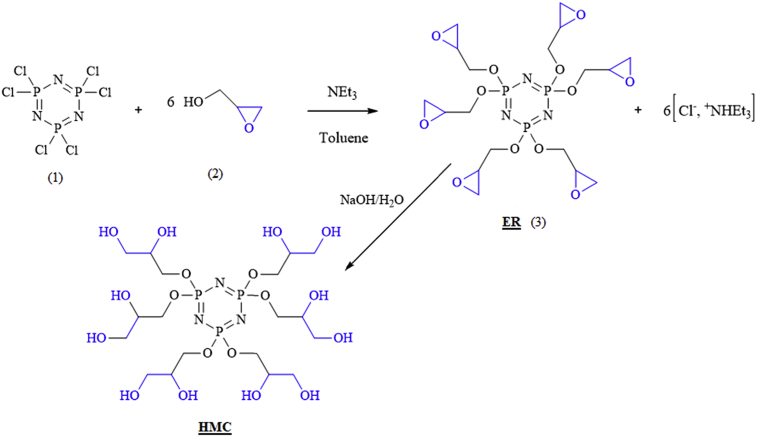

Carbon steel specimens were used as working (test) material. The corrosive medium of 3% NaCl concentration was manufactured by dilution with distilled water. The inhibition effect of HMC was tested at four different concentrations denoted by, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5 and 10−6 M. The inhibitor, HMC was synthesized according a reported procedure [6]. In brief, a mixture of an (2,3-epoxy-1-propanol) (2) compound (2g) and toluene (14.25mL) containing 2.22 g of triéthyl amine at room temperature. The mixture was cooled (ice-water). After was added 1.5 g of hexachloro cyclotriphosphazene (1) and toluene (7.5 mL) in two-necked round bottom flask, fitted with a condenser and a magnet stir bar was added drop wise for 3 h. After the addition was completed, the stirring was continued again for another 45 h at room temperature. The residual solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator in order to obtain the desired brown viscous solution of resin (3). After we take 5 g of product obtained epoxy resin (ER) (3) and added 10 mL of basic solution containing 2.1 g of NaOH. The mixture was neutralized, filtered and dried by Na2SO4 and to remove water.

Schematic diagram for the preparation of the HMC is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A representative scheme showing the total synthesis of Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2-diol) cyclotriphosphazene (HMC).

The structure of the produced was verified by 1H NMR and FT-IR spectroscopic characterization techniques. HMC: brown solid product, very soluble in water, yield 95%; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δppm = 2.7 (dd, 2H, -O-CH2), 3.38 (m, 1H, CH), 4 (dd, 2H, CH2).31P-NMR: δppm = 9.32 (s). FTIR (cm−1):1266 and 1200 (P=N stretching), 1013 (P-O-C), 2927, 2965 (asymmetric and symmetric γ of C–H units), 2800, 3600 (–OH).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Weight loss measurements

The weight loss analysis was carried out using the carbon steel of previously reported composition and procedure as described in our earlier studies [20, 21]. The gravimetric parameters were derived using following equations [22]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where W0 and Wi represent the weight loss values without and with HMC, respectively, t(h) is the immersion time and S is the total surface area of the metal sample.

2.2.2. Electrochemical measurements

Instruments and experimental procedures were similar as described in our previous reported literatures [23, 24, 25].

From EIS and polarization techniques, inhibition effect of HMC was evaluated using Eqs. (4) and (5).

The inhibition efficiency ηEIS% is calculated from resistance polarization Rp of HMC given by Eq. (5):

| (4) |

| (5) |

where, Rp0 and Rp represent the resistance polarization values without and with HMC, respectively. Whereas, i0corr and icorr represent the corrosion current density values without and with the inhibitor respectively.

2.2.3. Computational details

DFT on the HMC in its neutral as well as solvated phase was carried out using Gaussian 09 similar to our previously reported procedures [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33].

Several DFT parameters were computed using following relationships [34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48]: As per the theorem of Koopman, the values of frontier molecular orbitals can be correlated with ionization potential (I) as well as electron affinity (A) as per the Eqs. (6) and (7). The energies the energies are highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO) and energy gap (ΔE = ELUMO-EHOMO) have been calculated. Employing the magnitude of A and I, several other DFT indices like electronegativity (χ), global harness (η) and softness (σ) were computed for the forms of HMC as per the Eqs. (8)– (10). It is well documented that metal inhibitor bindings involve donor-acceptor phenomenon. The fraction of electron transfer (ΔN) by HMC molecules was computed as per the Eq. (11). Which is the initial molecule-metal interaction energy (Δψ) and the inhibitor molecule and the metal surface as per the Eqs. (12) and (13).

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Where, where ϕ corresponds to the work function, which is used as the appropriate measure of electronegativity of iron, and ηFe = 0. The theoretical value of ϕ is 4.82 eV for Fe (110) plan which is reported to have the higher stabilization energy. Eq. 13implies that when η > 0 or ΔEb-d< 0, back-donation from the molecule to metal is energetically favored.

It is very necessary to identify the reactive centres present within the inhibitor molecules. The Fukui Indices (FIs) analyses help to determine and recognize the sites of the molecule which are responsible for nucleophilic or electrophilic reactions. The presence of the nucleophilic or electrophilic center facilitates the interaction of the inhibitor molecules with the surface atoms of the metal.

Fukui functions for nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks are obtained from finite difference approximations as the follows:

| (14) |

| (15) |

ρk(N),ρk(N-1) and ρk(N+1) are the gross electronic populations of the site k in neutral, cation and anion, respectively.

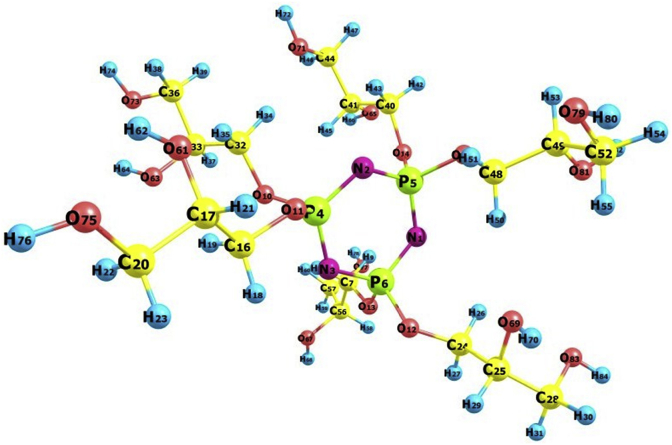

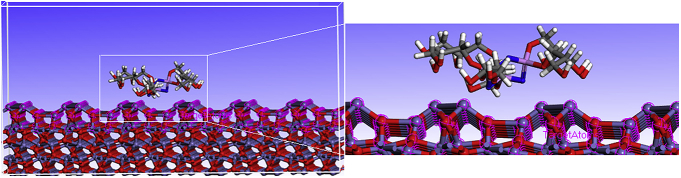

Monte Carlo simulations help us to find the most stable adsorption sites on metal and metal oxide surfaces through finding the low energy adsorption sites on both periodic and non-periodic substrates or to investigate the preferential adsorption of mixtures of adsorbate components. In order to investigate the most suitable adsorption modes for the neutral inhibitor, the HMC molecule and Fe2O3 surface were prepared. In this study, the HMC molecule was drawn and the hydrogens were adjusted, then the molecules were cleaned using sketch tools available in the Materials Visualizer. The sketched and fully optimized geometry structure of HMC is shown in Fig. 8. The molecule that are shown in Fig. 8 were optimized (i.e., energy minimizing) in the Monte Carlo simulations using the forcite module and the Condensed- Phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies (COMPASS) force field. For cite is an advanced classical mechanics tool that allows energy calculations and geometry optimizations. COMPASS force field which used to optimize the structures the HMC of all components of the system of interest (Fe+ inhibitor) and represents a technology break-through in force field method. COMPASS is the first ab initio force field that enables accurate and simultaneous prediction of chemical properties (structural, conformational, vibrational, etc.) and condensed-phase properties (equation of state, cohesive energies, etc.) for a broad range of chemical systems. It is also the first high quality force field to consolidate parameters of organic and inorganic materials. Materials Studio provides the unit cell structures of metal oxides with the associated experimental lattice parameters. Metal oxide surfaces were prepared by employing the desired cleavage planes hkl (110), Using the surface builder module of Materials Studio. The Metal oxide surface must be large enough to accommodate the inhibiter molecules; therefore, the constructed surface was enlarged by periodic replication to triple U ×V (3 × 3) in order to expose a more realistic surface area for docking the inhibitor molecules. The surface with parameters of 45.7 and 27.9 Å was produced. It is important that the size of the vacuum is great enough such that the non-bonded calculation for the adsorbate does not interact with the periodic image of the bottom layer of atoms in the surface; thus, a vacuum slab with thickness 31.7 Å was built using Crystal Builder. A low-energy adsorption site is identified by carrying out a Monte Carlo search. This process is repeated to identify further local energy minima. During the course of the simulation, adsorbate molecule are randomly rotated and translated around the substrate. The configuration that results from one of these steps is accepted or rejected according to the selection rules of the Metropolis Monte Carlo method. The Monte Carlo (MC) simulation was performed using Materials Studio 5.5 program [49, 50, 51, 52, 53].

Fig. 8.

The optimized geometrical structure of the HMC species. The indicated numbers are used for Fukui indices.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Weight loss measurements (WL)

The WL parameters derived for steel corrosion after 24 h immersion time in 3 % NaCl solution is listed in Table 1. Visualization of the results showed that inhibition performance of HMC is concentration dependent it increases on increasing the concentration of HMC and maximum efficiency was observed at 10−3 M. The increase in the inhibition effectiveness of HMC with their concentration is might be attributed to the increase in surface coverage values at higher concentrations.

Table 1.

Wcorr and ηWL obtained from weight loss measurements for carbon steel in 3% NaCl with and without various concentration of HMC at 298 K for 24 h.

| Inh | C (M) | Wcorr (mg/cm2h1) | ηWL(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | – | 3 | – |

| 10–6 | 0.23 | 92 | |

| HMC | 10–5 | 0.22 | 93 |

| 10–4 | 0.17 | 94 | |

| 10–3 | 0.12 | 96 |

The process of corrosion inhibition was highly influenced by the temperature. For the purpose of further understanding the effect of temperatures, the corrosion inhibition ability of HMC in 3% NaCl solution was studied at various temperatures in the rang 298–328 K for 24 h of immersion. The evolution of Wcorr and ηWL with various temperature for carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution in the without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of temperature on the corrosion rate (Wcorr) and corrosion current densities (icorr) for carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution in the absence and addition10−3 M of HMC.

| T (K) | Wcorr (mg/cm2h1) |

icorr μA/Cm2 |

ηWL (%) | ηPDP (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 10−3 M of HMC | Blank | 10−3 M of HMC | – | – | |

| 298 | 3 | 0.12 | 280 | 3 | 96 | 99 |

| 308 | 5.51 | 0.41 | 345 | 23.4 | 92 | 93 |

| 318 | 8.89 | 1.31 | 556 | 85.8 | 85 | 85 |

| 328 | 11.45 | 2.05 | 706 | 137.5 | 82 | 80 |

The results indicate that the values of ηWL obtained from the weight loss for carbon steel corrosion in 3% NaCl solution in the without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC at different temperatures decreased with increasing temperature. The maximum value of ηWL% obtained for 10−3 M of HMC is 96 % at 298 K. This behavior indicates desorption of inhibitor molecule.

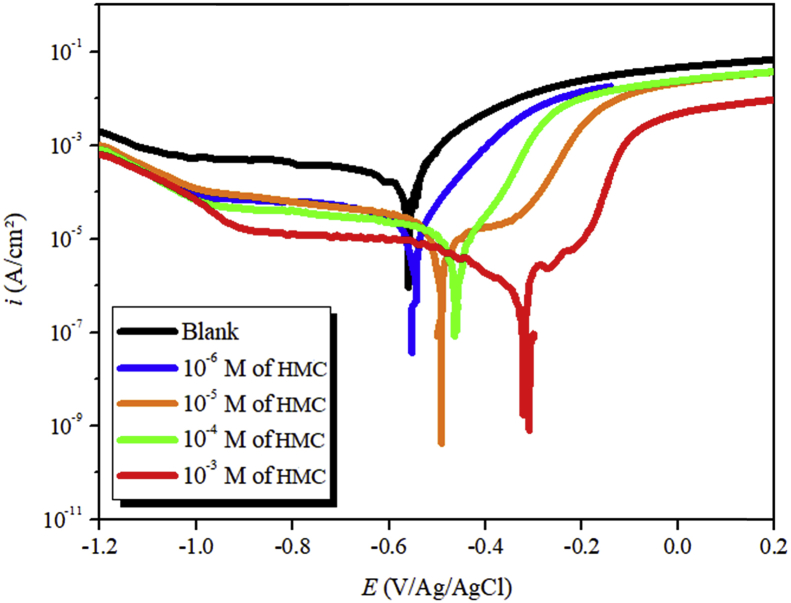

3.2. Potentiodynamic polarization measurements (PDP)

The PDP curves for carbon steel in 3 % NaCl are shown in Fig. 2. Parameters are presented in Table 3. Carbon steel readily undergoes anodic metallic dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution reactions using following schemes.

Fig. 2.

PDP curves for carbon steel corrosion in 3% NaCl solution containing different concentrations of HMC.

Table 3.

PDP parameters for carbon steel corrosion in 3% NaCl solution with and without addition of different concentrations of HMC.

| Inh | C (M) | Ecorr (mV/Ag/AgCl) | icorr (μA/cm2) | βa (V−1) | −βc (V−1) | ηPDP% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | – | −559 | 280 | 0.12 | 0.12 | – |

| 10–6 | −552 | 40 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 85 | |

| HMC | 10–5 | −498 | 27 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 90 |

| 10–4 | −463 | 14 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 94 | |

| 10–3 | −320 | 3 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 99 |

Anodic dissolution reactions [54]:

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

Cathodic hydrogen evolution reactions:

| (21) |

| (22) |

However, in its presence HMC forms protective inhibitive barrier which separates metal from the aggressive 3 % NaCl solution and protect from corrosion.

From the results obtained, the consequences is was perceived that icorr on the two cathodic and anodic polarization branches decrease in the presence of the HMC. Correspondingly, the inhibition efficacy increases by increasing the concentration of the HMC. The maximum efficiency of 99 % was obtained at 10−3 M. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3, with the addition of HMC molecules shifts corrosion potential is shifted to more anodic potential and also shows a significant change the anodic polarization branches. Anodic dominance of the HMC can be easily observed from the results presented in the table [55]. These results suggest that HMC molecules reduces the anodic metallic dissolution and retards the reduction of oxygen.

The influence of temperature on the various corrosion parameters icorr and ηPDP% obtained from the PDP of carbon steel was studied in 3% NaCl solution in the temperature rang (298–328 K)without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC. Results are listed in Table 2.

From the results of Table 2 shown that, as the temperature increased in in 3% NaCl solution in the without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC, the values of icorr increase and ηPDP% decrease. This result can be explaining by desorption of HMC molecules from carbon steel surface.

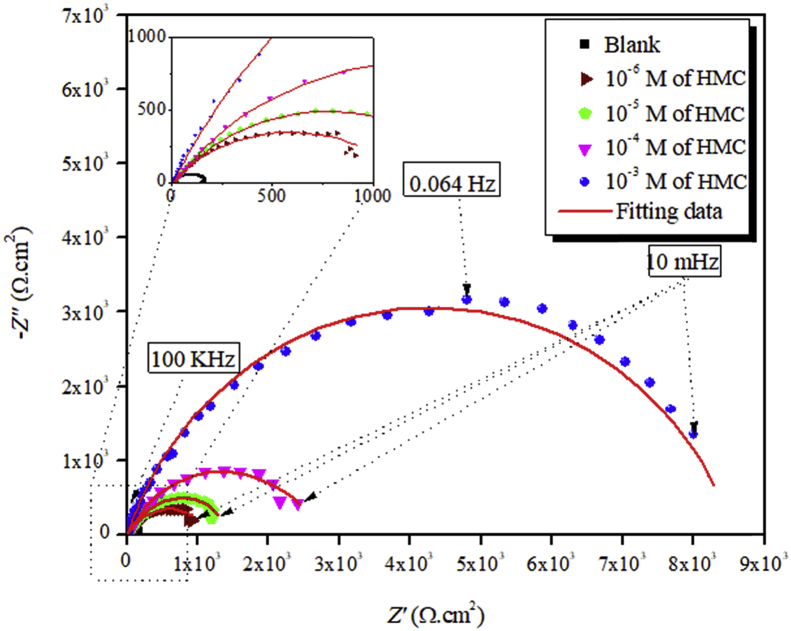

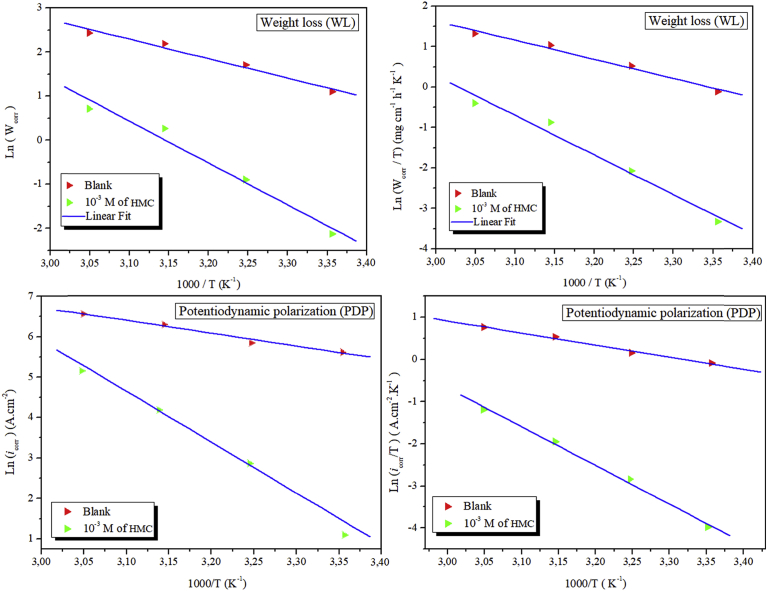

3.3. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements

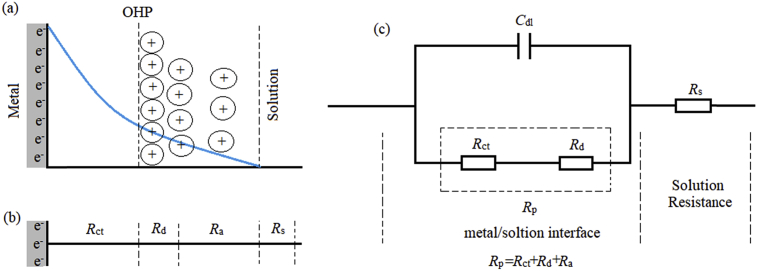

Nyquist plots for the carbon steel electrode in 3% NaCl solution and containing various concentrations of HMC after 30 min of immersion time are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Nyquist diagrams for carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution containing different concentrations of HMC.

It can be seen that in the absence of inhibitor, Nyquist plot contain only one semicircle. This indicates that corrosion on the carbon steel surface is mainly controlled by the charge transfer process [56, 57]. In Nyquist plot, difference in the lower frequency and higher frequency in the real axis is generally considered as charge transfer resistance (Rct). The charge transfer resistance must be consistent with the resistance between metal and Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP). Thus, the resistance coming from the metal/solution interface in absence of the inhibitor is mainly due to the charge transfer resistance (Rct), diffuse layer resistance (Rd) and accumulation resistance (Ra). Therefore, along with Rct, Rd and Ra have to be taken in account. Thus, difference in the lower frequency and higher frequency in the real axis is considered as polarization resistance (Rp). It is also seen from the Nyquist plot that the diameter of semi-circle is concomitantly increased in the presence of the inhibitor. This phenomenon suggests the formation of protective layer on the metal surface. Thus, in presence of inhibitor film resistance (Rf) have to be considered in the polarization resistance (Rp). So, in presence of inhibitor, Rp is designated as Σ (Rct + Rd + Ra + Rf). The addition of HMC to the aggressive solution leads to a change of the impedance diagrams in both shape and size, which a depressed semicircle at the high frequency part of the spectrum was observed and a second time constant appeared at low frequency region. The first capacitive loop appearing at high frequency region was attributed to the charge transfer resistance and the diffuse layer resistance, the second one at low frequencies related to the adsorption of inhibitor molecules on the metal surface and all other accumulated kinds at the metal/solution interface (inhibitor molecules, corrosion products, etc.). As seen from Fig. 3, the Rp values increased with the HMC concentration, which can be attributed to the formation of a protective over layer at the metal surface, which becomes a barrier for the mass and the charge transfers. The double layer can be represented by the electrical equivalent circuit diagrams to the model metal/solution interface. The corresponding electrical equivalent circuit model for the carbon steel in uninhibited solution is given in Fig. 4c with a schematic representation of the potential distributions on the metal/solution interface (Fig. 4a) and the resistances related to the double layer (Fig. 4b). According to Fig. 4, the Rp includes the Rct, the Rd and all the other accumulated kinds of ions, corrosion products, etc. at metal/solution interface. The Rct must be corresponded to the resistance between the metal and OHP (outer Helmholtz plane). All the other resistances must be considered as the simple resistance on the current crossing away. In the case of the inhibited solutions, related electrical equivalent circuit model is given in Fig. 5b with a schematic representation of metal/solution interface (Fig. 5a) [58, 59, 60].

Fig. 4.

The potential distributions on the metal/solution interface (a), the resistances related double layer (b), and proposed electrical equivalent circuit diagram for blank solution (c).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of metal/inhibitor/solution interface (a) and proposed equivalent electrical circuit diagram for EIS results of the carbon steel in inhibited solutions (b).

The obtained Nyquist plots have been fitted using these equivalents circuits where the constant phase element and the polarization resistance are in parallel combination and these two are connected in series with the electrolyte resistance (Rs). The constant phase element is defined by the following Eq. (23) [59]:

| (23) |

Where, Q is the proportionality coefficient, ω represents angular frequency, i is the imaginary unit and n is a measure of surface irregularity. For whole number of n = 1, 0, -1, CPE represent a capacitance (C), resistance (R) and inductance, respectively.

A direct correlation between the polarization resistance and double layer capacitance (Cdl) at the metal/solution interface is obtained by the following Eq. (24):

| (24) |

The electrochemical parameters values are listed in Table 4. Results depicted in Table 4 shows that Rp value increases with increasing the concentration of HMC. It may suggest that a protective layer has been formed on the electrode surface. This layer creates a barrier for charge and mass transfer at the metal-solution interface [59]. It is also observed that with increasing inhibitor concentration the Cdl values are decreased, which can be described by an increase in the thickness of electric double layer or by the decrease of local dielectric constant [59].

Table 4.

EIS parameters for carbon steel corrosion in 3% NaCl solution with and without addition of different concentrations of HMC.

| Inh |

C |

Rs |

Rp |

Cdl (μF/cm2) | ηEIS% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M) | (kΩ.cm2) | (kΩ.cm2) | |||

| Blank | – | 10 | 0.165 | – | – |

| 10–6 | 15 | 1.0 | 165 | 85 | |

| HMC | 10–5 | 12 | 1.6 | 141 | 90 |

| 10–4 | 12 | 2.7 | 68 | 94 | |

| 10–3 | 8 | 9 | 52 | 98 |

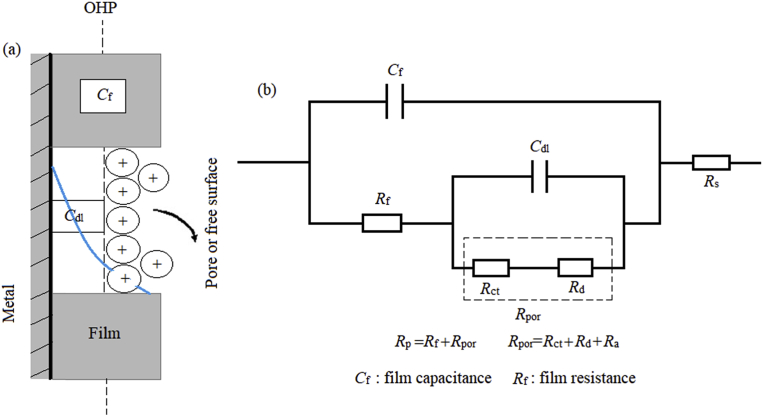

3.4. Adsorption studies

The adsorption isotherm is frequently utilized to inspect the adsorption mechanism between the inhibitors and metal atoms at the metal surface. The most utilized adsorption isotherm is Langmuir [61]. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm is shown in Eq. (25).

| (25) |

where θ is the surface coverage degree and Kads is the adsorption process.

Langmuir isotherm and the experimental data have a good linear relationship for the adsorption behavior of the investigated HMC, representing that adsorption of HMC on metallic surface comply with Langmuir adsorption isotherm. The association between Cinh and Cinh/θ yielded straight lines with intercept of Kads as shown in Fig. 6. From the Kads values, the are calculated using Eq. (26) [62]:

| (26) |

where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol. K), value 55.55 is the water concentration in the solution (mol/L). In general, a high value of Kads and low value of indicating a strong interaction and a strong adsorption on the metal surface [63]. The calculated value of Kads (1.18 M−1×106)) and (−44.57 kJ mol−1) indicates that HMC exhibits a strong interactions with carbon steel surface (chemisorption) [64].

Fig. 6.

Langmuir adsorption isotherm on weight loss of carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution containing different concentrations of HMC after 24 h at 298 K.

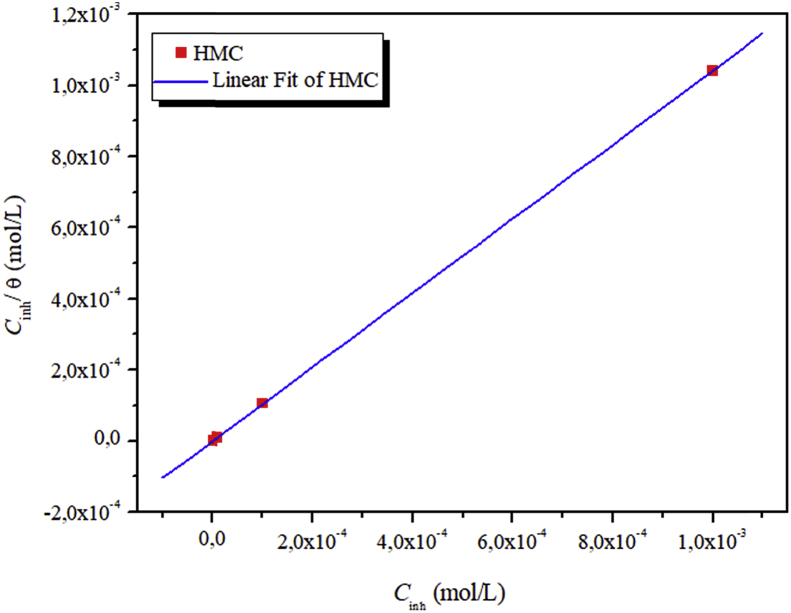

3.5. Effect of temperature

Generally, increase in the temperature causes significant decrease in the protection ability of the inhibitor molecules. The influence of temperature can be best explained with the aid of Arrhenius Eqs. (27) and (28) [65, 66]:

| (27) |

| (28) |

Arrhenius plots is shown in Fig. 7. Moreover, the Arrhenius equation can be converted Eqs. (29) and (30) (transition state equations) as shown [67, 68]:

| (29) |

| (30) |

Fig. 7.

The relationship between Ln (Worr), Ln (icorr), Ln (Wcorr/T) and Ln (icorr/T) as a function of 1/T in 3% NaCl solution without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC.

A is the Arrhenius exponent, T is temperature, N is Avogadro's constant and other symbols have their usual meaning. Several parameters such as Ea, ΔHa and ΔSa calculated using Arrhenius and transition state plots (Fig. 7) are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Values of Ea, ΔHa and ΔSa for carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution without and with addition 10−3 M of HMC.

| Method | C (M) | Ea (kJ/mol) | ΔHa (kJ/mol) | ΔSa (J.mol−1 K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL | Blank | 35.82 | 39.22 | −66.06 |

| 10−3 M of HMC | 78.95 | 81.52 | +49.53 | |

| PDP | Blank | 26.40 | 23.82 | −118.40 |

| 10−3 M of HMC | 79.50 | 76.45 | +26.25 |

The positive value of ΔHa reveals the endothermic nature of metal-inhibitor interactions [69], whereas increased value of ΔSa suggested that replacement of the water molecules from ER that results into the corresponding increase in the disordering (randomness) on the metallic surface.

3.6. Theoretical studies

3.6.1. Quantum chemical calculation

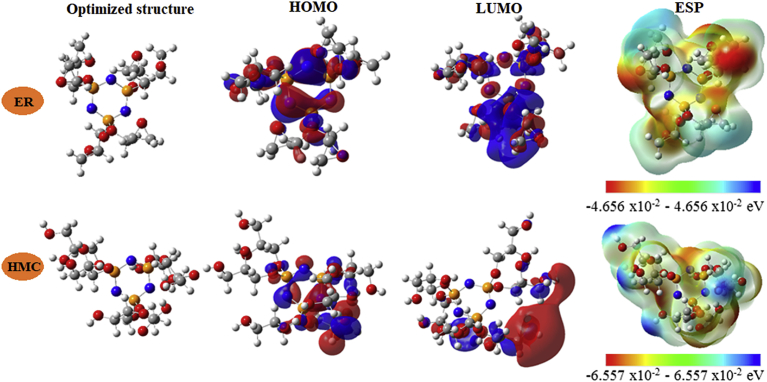

The anticorrosive efficiency of the Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2-diol) cyclotriphosphazene (HMC) was investigated by DFT and MC simulations. It is worth mentioning that the corrosion effect of chemical inhibitors is accompanied to its adsorption via electronic interaction with the metal's surface. Recently, quantum chemical calculation has been used to provide the scientists more information about structural properties of the chemical inhibitors. On the other hand the adsorption mechanism can be used to study the chemical reactivity of the inhibitors. The quantum chemical indicators, such as, EHOMO, ELUMO, Energy gap, ΔE (EHOMO–ELUMO), electronegativity, global softness, chemical hardness and softness and the number of electrons transferred are very important and useful parameters to study the anticorrosive effect of the investigated molecule. Table 6 presents our computed results of the considered inhibitors in its neutral and protonated forms in both gas and aqueous phases. Fig. 9 shows the optimized geometrical structures and the FMO surfaces (HOMO and LUMO) while the electrostatic potential maps (ESP) are presented in Fig. 7.

Table 6.

Optimized energy (in hartree), dipole moment (μ*) in Debye and Quantum chemical parameters in eV of ER and HMC in both gas phase and aqueous solution.

| Gas |

Solution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | HMC | ER | HMC | |

| Energy (a.u.) | −2795.389255 | −3254.345223 | −2795.422351 | −3254.381590 |

| EHOMO(eV) | −7.211 | −6.713 | −7.481 | −7.370 |

| ELUMO (eV) | 0.752 | 0.476 | 0.631 | 0.665 |

| I | 7.963 | 7.189 | 8.112 | 8.036 |

| A | −0.752 | −0.476 | −0.631 | −0.665 |

| ΔE | 7.963 | 7.189 | 8.112 | 8.036 |

| χ | 3.606 | 3.357 | 3.741 | 3.685 |

| η | 4.358 | 3.833 | 4.371 | 4.350 |

| σ | 0.229 | 0.261 | 0.229 | 0.230 |

| ΔN110 | 0.139 | 0.191 | 0.139 | 0.191 |

| Δψ | 0.661 | 0.866 | 0.608 | 0.631 |

| ΔEb-d | −1.089 | −0.958 | −1.093 | −1.088 |

Fig. 9.

Optimized geometrical structures, HOMO and LUMO surfaces and electrostatic potential map (ESP) of ER (non-protonated) and HMC (protonated). All values of the colored scales are in eV.

A close inspection of the optimized structure of the investigated inhibitor (Fig. 9) indicates that the HOMO and LUMO surfaces of the non-protonated species are distributed almost over the central part of the molecule except of the HOMO structure of the non-protonated species, in which a distribution was shown over the one of the epoxy groups. This means that the inhibitor in its both forms has a good ability to donate electron to an acceptor (metal surface). The EHOMO is a measure of a molecule's tendency to receive an electron from donor species. It is well known that lower ELUMO and/or higher EHOMO benefit(s) higher corrosion inhibition strength [17, 18, 70, 71]. It is clearly obvious from Table 6 that the EHOMO of the protonated inhibitor in aqueous medium is found to be higher than of the noon-protonated species. In contrast, the value of ELUMO is not in agreement with our finding.

Theoretically, another important to characterize the chemical reactivity on an inhibitor is the energy gap (ΔEgap). Energy gap shows the capability of inhibitor to be an effective corrosion inhibitor or not [72, 73]. It was found that when the ΔEgap decreases, the adsorption efficiency between the metal surface and the inhibitors increases, because the energy to remove an electron from the HOMO must be lower [17, 18, 74].

Table 6, show that the energy break values for the non-protonated (ER) and protonated HMC species are 8.112 and 8.036 eV, respectively. The protonated form has inferior energy break (ΔEgap) compared to the non-protonated one. This finding indicates that the adsorption performance on the steel surface of the non-protonated form is energetically favored.

Another very important, both experimental and theoretical, quantum chemical descriptor is the chemical hardness, which describes the resistance to electron cloud polarization or deformation of chemical species. Additionally, chemical hardness is a measure of the stability of the chemical molecule, which has a high energy gap. On the other hand, soft molecule, which has low energy gap can be good corrosion inhibitor in view of the fact that soft molecule can very readily give electron of HOMO to metals [17, 18, 70, 71]. An inspection of Table 7 shows that the protonated species in aqueous medium is less harder and less softer than the neutral species.

Table 7.

Fukui indices of the protonated (HMC) tested inhibitor in aqueous medium calculated by DFT/6-311G (d,p).

| f+ | f- | f+ | f- | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(1) | 0.143 | 0.002 | C(36) | 0.029 | 0.029 |

| N(2) | 0.079 | −0.002 | C(40) | 0.017 | 0.012 |

| N(3) | 0.064 | 0.004 | C(41) | −0.009 | 0.004 |

| P(4) | 0.017 | −0.001 | C(44) | 0.037 | 0.032 |

| P(5) | 0.016 | 0.005 | C(48) | −0.011 | −0.006 |

| P(6) | 0.017 | 0.004 | C(49) | 0.019 | 0.010 |

| C(7) | −0.011 | −0.001 | C(52) | 0.036 | 0.034 |

| O(10) | 0.028 | 0.003 | C(56) | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| O(11) | 0.023 | 0.000 | C(57) | 0.032 | 0.020 |

| O(12) | 0.026 | 0.000 | O(61) | 0.026 | 0.018 |

| O(13) | 0.036 | 0.002 | O(63) | 0.050 | 0.019 |

| O(14) | 0.009 | 0.002 | O(65) | 0.017 | 0.034 |

| O(15) | 0.037 | 0.003 | O(67) | 0.023 | 0.009 |

| C(16) | 0.013 | 0.008 | O(69) | −0.001 | 0.087 |

| C(17) | 0.011 | 0.007 | O(71) | −0.001 | 0.138 |

| C(20) | 0.026 | 0.022 | O(73) | 0.019 | 0.083 |

| C(24) | 0.005 | 0.021 | O(75) | 0.018 | 0.116 |

| C(25) | 0.015 | 0.013 | O(77) | 0.012 | 0.060 |

| C(28) | 0.036 | 0.065 | O(79) | 0.013 | 0.050 |

| C(32) | 0.013 | −0.002 | O(81) | 0.038 | 0.009 |

| C(33) | 0.009 | 0.012 | O(83) | 0.006 | 0.067 |

The value of ΔN reveals the capability of the examined inhibitor to transfer its electrons to metal if ΔN > 0 and vice versa if ΔN < 0. Based on this principle, it is apparent from the results in Table 6 that the tested inhibitor in its two forms in both gas and aqueous phases has higher propensity to give its electrons to a metal surface.

Kovacevic and Kokalj [75] introduced another important quantum parameter, which is the initial molecule-metal interaction energy (Δψ). In our work, Δψ has been calculated for the investigated inhibitor in its neutral and protonated forms in both gas and aqueous phases. The results are also presented in Table 6. The results indicate that the trend of Δψ is also protonated > neutral in both phases, meaning that the protonated form is better than the neutral one.

Finally, Gomez et al [44] proposed the simple charge transfer theory for donation and back-donation of charges proposed. In this theory Gomez proved that the interaction between the inhibitors and substrate surface can be probably affected by the electronic back-donation process. According to our results given in Table 6, the calculated ΔEb−d exhibits the trend: protonated > neutral in both gas and aqueous phases.

3.6.2. Fukui functions

The Fukui indices, in corrosion inhibition study, are an important local descriptor to investigate the relationship of the inhibitors with mild steel surface in terms of structure-activity. Herein, the current research affords an exciting chance to enhance our knowledge of electron donating ability (i.e. nucleophilic fk+), and electron accepting ability (i.e. electrophilic fk−) of the inhibitor under probe. The Fukui indices of the protonated species of the tested inhibitor in the aqueous phase have been calculated based on the Mulliken charges by using Eqs. (14) and (15). The results are summarized in Table 7. The indicated numbers of the atoms are given Fig. 8. These results agree well the electronic distribution of the FMO orbitals (HOMO and LUMO), which were shown in Fig. 9.

3.7. Monte Carlo simulation

To get further information and a better understanding of how the HMC molecule behave and interact on an iron oxide surface, Monte Carlo simulation were performed on a system with the inhibitor molecule on an iron oxide Fe2O3 surface, as presented in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Adsorption mode of the HMC on the Fe (110) surface.

The strength of corrosion inhibitors absorbed on iron oxide surface can be expressed by the adsorption energy (Eads). In the present paper, the adsorption energies were calculated from the average adsorption energy of the obtained equilibrium configurations. The highest and lowest obtained Eads values are -1464.57, -1442.11, kJ/mol respectively. A higher negative value of Eads means that the adsorption of HMC molecule is strong, stable and therefore spontaneous adsorption on Fe (110) surface. As can be seen in Fig. 10, HMC molecule is adsorbed in a parallel orientation to the metal surface through the (N, P, O) as active sites [76, 77, 78, 79,].

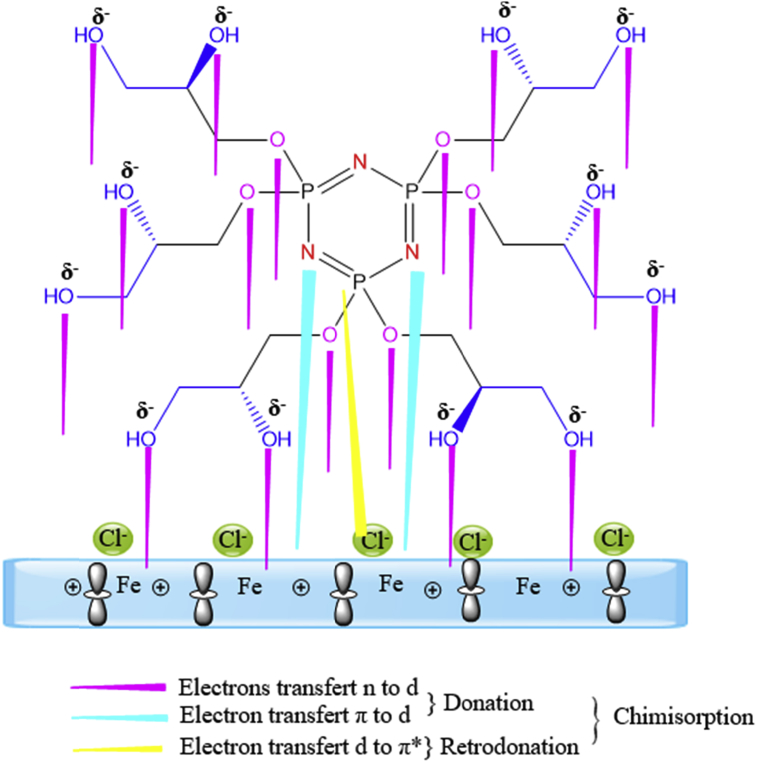

3.8. Inhibition mechanism

Experimental data, the computational calculations provided a great help in explaining the mechanism of inhibition of mode of adsorption of inhibitor and identifying the active sites. Generally, the charge on the metal, chemical structure (electronic density at the donor site) of inhibitor, type of interaction between inhibitor and metal influence the adsorption process. The HMC inhibitor has electronegative donor atoms such as nitrogen and oxygen atoms and π-electrons of the aromatic ring. These electron-rich donor atoms in addition with π-electrons of the aromatic ring favor adsorption of HMC inhibitor, thus leads to a strong interaction with the steel surface. As the observed outcome of the present investigation, HMC under goes comprehensive adsorption (involving chemisorption), the possible modes of interaction of HMC with the carbon steel surface a result of a combination of a three kinds of interactions (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Mechanism of HMC adsorption on carbon steel in 3% NaCl solution.

4. Conclusions

-

1.

The synthesized Hexa (3-methoxy propan-1,2 diol) cyclotriphosphazene was significantly improved the corrosion inhibition efficiency of carbon steel in 3% NaCl, and their inhibition efficiency increases with increasing concentration.

-

2.

The results of weight loss (WL) study were consistent with results derived from PDP and EIS studies.

-

3.

The adsorption of HMC on the carbon steel surface from 3 % NaCl obeys a Langmuir adsorption isotherm.

-

4.

The measurement of potentiodynamic polarization demonstrated that inhibitor HMC effectively suppressed corrosion process and classified as anodic -type inhibitor.

-

5.

EIS studies revealed the adsorption of inhibitor and are confirmed by increase in Rp and decrease in Cdl values, respectively.

-

6.

The values of indicating strongly interaction between inhibitor molecules and carbon steel.

-

7.

DFT computational study shows that the inhibitive strengths of the HMC correlate with their relative reactivity and the presence of highly electronegative atoms.

-

8.

Monte Carlo simulation suggest that the HMC molecules present a parallel adsorption model on iron substrate.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ahmed El Harfi, Mustapha El Gouri, Omar Dagdag, Zaki Safi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Nuha Wazzan, U. Pramod Kumar, Ramzi T.T. Jalgham: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Chandrabhan Verma, Eno Ebenso: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Chandrabhan Verma was supported by the North-West University (Mafikeng Campus) South Africa under a postdoctoral fellowship scheme.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Omar Dagdag, Email: omar.dagdag@uit.ac.ma.

Zaki Safi, Email: z.safi@alazhar.edu.ps.

References

- 1.Verma C., Quraishi M.A., Kluza K., Makowska-Janusik M., Olasunkanmi L.O., Ebenso E.E. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1M HCl by D-glucose derivatives of dihydropyrido [2, 3-d: 6, 5-d′] dipyrimidine-2, 4, 6, 8 (1H, 3H, 5H, 7H)-tetraone. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44432. doi: 10.1038/srep44432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoun S.B. On the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in 1 M HCl with a pyridinium-ionic liquid: chemical, thermodynamic, kinetic and electrochemical studies. RSC Adv. 2017;7(58):36688–36696. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Bakri Y., Guo L., Harmaoui A., Ali A.B., Essassi E.M., Mague J.T. Synthesis, crystal structure, DFT, molecular dynamics simulation and evaluation of the anticorrosion performance of a new pyrazolotriazole derivative. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1176:290–297. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmmod A.A., Kazarinov I.A., Khadom A.A., Mahood H.B. Experimental and theoretical studies of mild steel corrosion inhibition in phosphoric acid using tetrazoles derivatives. J. Bio Tribo Corr. 2018;4(4):58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra A., Verma C., Chauhan S., Quraishi M.A., Ebenso E.E., Srivastava V. Synthesis, characterization, and corrosion inhibition performance of 5-aminopyrazole carbonitriles towards mild steel acidic corrosion. J Bio Tribo Corr. 2018;4(4):53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rbaa M., Lgaz H., El Kacimi Y., Lakhrissi B., Bentiss F., Zarrouk A. Synthesis, characterization and corrosion inhibition studies of novel 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives on the acidic corrosion of mild steel: experimental and computational studies. Mater. Dis. 2018;12:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh A., Ansari K.R., Haque J., Dohare P., Lgaz H., Salghi R., Quraishi M.A. Effect of electron donating functional groups on corrosion inhibition of mild steel in hydrochloric acid: experimental and quantum chemical study. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018;82:233–251. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinoza-Vázquez A., Rodríguez-Gómez F.J., Vergara-Arenas B.I., Lomas-Romero L., Angeles-Beltrán D., Negrón-Silva G.E., Morales-Serna J.A. Synthesis of 1, 2, 3-triazoles in the presence of mixed Mg/Fe oxides and their evaluation as corrosion inhibitors of API 5L X70 steel submerged in HCl. RSC Adv. 2017;7(40):24736–24746. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beşli S., Coles S.J., Davies D.B., Eaton R.J., Kılıç A., Shaw R.A. Competitive formation of spiro and ansa derivatives in the reactions of tetrafluorobutane-1, 4-diol with hexachlorocyclotriphosphazene: a comparison with butane-1, 4-diol. Polyhedron. 2006;25(4):963–974. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Gouri M., El Bachiri A., Hegazi S.E., Rafik M., El Harfi A. Thermal degradation of a reactive flame retardant based on cyclotriphosphazene and its blend with DGEBA epoxy resin. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2009;94(11):2101–2106. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha S.K., Murmu M., Murmu N.C., Obot I.B., Banerjee P. Molecular level insights for the corrosion inhibition effectiveness of three amine derivatives on the carbon steel surface in the adverse medium: a combined density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation study. Surf. Interfaces. 2018;10:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagdag O., El Harfi A., Cherkaoui O., Safi Z., Wazzan N., Guo L. Rheological, electrochemical, surface, DFT and molecular dynamics simulation studies on the anticorrosive properties of new epoxy monomer compound for steel in 1 M HCl solution. RSC Adv. 2019;9(8):4454–4462. doi: 10.1039/c8ra09446b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A., Ansari K.R., Quraishi M.A., Lgaz H., Lin Y. Synthesis and investigation of pyran derivatives as acidizing corrosion inhibitors for N80 steel in hydrochloric acid: theoretical and experimental approaches. J. Alloy. Comp. 2018;762:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obot I., Obi-Egbedi N. Theoretical study of benzimidazole and its derivatives and their potential activity as corrosion inhibitors. Corros. Sci. 2010;52:657–660. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha S.K., Murmu M., Murmu N.C., Banerjee P. Evaluating electronic structure of quinazolinone and pyrimidinone molecules for its corrosion inhibition effectiveness on target specific mild steel in the acidic medium: a combined DFT and MD simulation study. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;224:629–638. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wazzan N.A., Obot I., Kaya S. Theoretical modeling and molecular level insights into the corrosion inhibition activity of 2-amino-1, 3, 4-thiadiazole and its 5-alkyl derivatives. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;221:579–602. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erdoğan Ş., Safi Z.S., Kaya S., Işın D.Ö., Guo L., Kaya C. A computational study on corrosion inhibition performances of novel quinoline derivatives against the corrosion of iron. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1134:751–761. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo L., Safi Z.S., Kaya S., Shi W., Tüzün B., Altunay N., Kaya C. Anticorrosive effects of some thiophene derivatives against the corrosion of iron: a computational study. Front. Chem. 2018;6:155. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:3533–3539. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobin M., Aslam R. Experimental and theoretical study on corrosion inhibition performance of environmentally benign non-ionic surfactants for mild steel in 3.5% NaCl solution. Proc. Saf. Environ. Protect. 2018;114:279–295. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiang Y., Zhang S., Xu S., Li W. Experimental and theoretical studies on the corrosion inhibition of copper by two indazole derivatives in 3.0% NaCl solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;472:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beniken M., Driouch M., Sfaira M., Hammouti B., Touhami M.E., Mohsin M.A. Anticorrosion activity of a polyacrylamide with high molecular weight on C-steel in acidic media: Part 1. J. Bio Tribo Corr. 2018;4(3):38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dagdag O., El Harfi A., Essamri A., El Gouri M., Chraibi S., Assouag M. Phosphorous-based epoxy resin composition as an effective anticorrosive coating for steel. Int. J. Integr. Care. 2018:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dagdag O., El Harfi A., Essamri A., El Bachiri A., Hajjaji N., Erramli H. Anticorrosive performance of new epoxy-amine coatings based on zinc phosphate tetrahydrate as a nontoxic pigment for carbon steel in NaCl medium. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2018:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagdag O., Hamed O., Erramli H., El Harfi A. Anticorrosive performance approach combining an epoxy polyaminoamide–zinc phosphate coatings applied on sulfo-tartaric anodized aluminum alloy 5086. J. Bio Tribo Corr. 2018;4(4):52. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chermette H. Chemical reactivity indexes in density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:129–154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch M., Trucks G., Schlegel H., Scuseria G., Robb M., Cheeseman J., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keith T., Millam J., Eppinnett K., Hovell W., Semichem R. Dennington II, Inc.; Shawnee Mission, KS: 2005. Gauss View 05. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becke A.D. Density functional calculations of molecular bond energies. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;84:4524–4529. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomasi J., Mennucci B., Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3094. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mennucci B., Cances E., Tomasi J. Evaluation of solvent effects in isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics and in ionic solutions with a unified integral equation method: theoretical bases, computational implementation, and numerical applications. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:10506–10517. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obot I., Gasem Z. Theoretical evaluation of corrosion inhibition performance of some pyrazine derivatives. Corros. Sci. 2014;83:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases—the evolution of a chemical concept. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1990;100:403–425. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parr R.G., Donnelly R.A., Levy M., Palke W.E. Electronegativity: the density functional viewpoint. J. Chem. Phys. 1978;68:3801–3807. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parr R.G., Pearson R.G. Absolute hardness: companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7512–7516. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson R.G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness: application to inorganic chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:734–740. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geerlings P., De Proft F., Langenaeker W. Conceptual density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1793–1874. doi: 10.1021/cr990029p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy R., Krishnamurti S., Geerlings P., Pal S. Local softness and hardness based reactivity descriptors for predicting intra-and intermolecular reactivity sequences: carbonyl compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:3746–3755. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez S. Inhibitory mechanism of mimosa tannin using molecular modeling and substitutional adsorption isotherms. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003;77:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutta A., Saha S.K., Banerjee P., Patra A.K., Sukul D. Evaluating corrosion inhibition property of some Schiff bases for mild steel in 1 M HCl: competitive effect of the heteroatom and stereochemical conformation of the molecule. RSC Adv. 2016;6:74833–74844. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu R., Qiu X., Shi Y., Deng M. Molecular dynamics simulation of the atomistic monolayer structures of N-acyl amino acid-based surfactants. Mol. Simulat. 2017;43:491–501. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sastri V., Perumareddi J. Molecular orbital theoretical studies of some organic corrosion inhibitors. Corrosion. 1997;53:617–622. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez B., Likhanova N., Dominguez-Aguilar M., Martinez-Palou R., Vela A., Gazquez J.L. Quantum chemical study of the inhibitive properties of 2-pyridyl-azoles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:8928–8934. doi: 10.1021/jp057143y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouanis M., Tourabi M., Nyassi A., Zarrouk A., Jama C., Bentiss F. Corrosion inhibition performance of 2, 5-bis (4-dimethylaminophenyl)-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole for carbon steel in HCl solution: gravimetric, electrochemical and XPS studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;389:952–966. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukui K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. Science. 1982;218:747–754. doi: 10.1126/science.218.4574.747. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1689733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukui K. World Scientific; 1997. The Role of Frontier Orbitals in Chemical Reactions, Frontier Orbitals and Reaction Paths: Selected Papers of Kenichi Fukui; pp. 150–170. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy R.K., Pal S., Hirao K. On non-negativity of Fukui function indices. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:8236–8245. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khaled K.F., El-Maghraby A. Experimental, Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations to investigate corrosion inhibition of mild steel in hydrochloric acid solutions. Arabian J. Chem. 2014;7(3):319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Musa A.Y., Kadhum A.A.H., Mohamad A.B., Takriff M.S. Experimental and theoretical study on the inhibition performance of triazole compounds for mild steel corrosion. Corros. Sci. 2010;52(10):3331–3340. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Awad M.K., Mustafa M.R., Elnga M.M.A. Computational simulation of the molecular structure of some triazoles as inhibitors for the corrosion of metal surface. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2010;959(1-3):66–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Musa A.Y., Jalgham R.T., Mohamad A.B. Molecular dynamic and quantum chemical calculations for phthalazine derivatives as corrosion inhibitors of mild steel in 1 M HCl. Corros. Sci. 2012;56:176–183. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khaled K.F. Monte Carlo simulations of corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 0.5 M sulphuric acid by some green corrosion inhibitors. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2009;13(11):1743–1756. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazumder M.A., Al-Muallem H.A., Faiz M., Ali S.A. Design and synthesis of a novel class of inhibitors for mild steel corrosion in acidic and carbon dioxide-saturated saline media. Corros. Sci. 2014;87:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashassi-Sorkhabi H., Asghari E. Effect of hydrodynamic conditions on the inhibition performance of l-methionine as a “green” inhibitor. Electrochim. Acta. 2008;54:162–167. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jamil H., Montemor M.F., Boulif R., Shriri A., Ferreira M.G.S. An electrochemical and analytical approach to the inhibition mechanism of an amino-alcohol-based corrosion inhibitor for reinforced concrete. Electrochim. Acta. 2003;48(23):3509–3518. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valcarce M.B., Vázquez M. Carbon steel passivity examined in solutions with a low degree of carbonation: the effect of chloride and nitrite ions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009;115(1):313–321. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solmaz R., Kardaş G., Culha M., Yazıcı B., Erbil M. Investigation of adsorption and inhibitive effect of 2-mercaptothiazoline on corrosion of mild steel in hydrochloric acid media. Electrochim. Acta. 2008;53(20):5941–5952. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saha S.K., Dutta A., Ghosh P., Sukul D., Banerjee P. Novel Schiff-base molecules as efficient corrosion inhibitors for mild steel surface in 1 M HCl medium: experimental and theoretical approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18(27):17898–17911. doi: 10.1039/c6cp01993e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.John S., Joseph A. Theoretical and electrochemical studies on the effect of substitution on 1, 2, 4-triazole towards mild steel corrosion inhibition in hydrochloric acid. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2012;19(3):195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pareek S., Jain D., Hussain S., Biswas A., Shrivastava R., Parida S.K. A new insight into corrosion inhibition mechanism of copper in aerated 3.5%(by weight) NaCl solution by eco-friendly imidazopyrimidine dye: experimental and theoretical approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loto R.T., Tobilola O. Corrosion inhibition properties of the synergistic effect of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde and hexadecyltrimethylammoniumbromide on mild steel in dilute acid solutions. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galai M., El Gouri M., Dagdag O., El Kacimi Y., Elharfi A., Ebn Touhami M. New hexa propylene glycol cyclotiphosphazene as efficient organic inhibitor of carbon steel corrosion in hydrochloric acid medium. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016;7:1562. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Obot I.B., Umoren S.A., Gasem Z.M., Suleiman R., El Ali B. Theoretical prediction and electrochemical evaluation of vinylimidazole and allylimidazole as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1 M HCl. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;21:1328–1339. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salhi A., Tighadouini S., El-Massaoudi M., Elbelghiti M., Bouyanzer A., Radi S. Keto-enol heterocycles as new compounds of corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in 1 M HCl: weight loss, electrochemical and quantum chemical investigation. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;248:340–349. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elfaydy M., Touir R., Ebntouhami M., Zarrouk A., Jama C., Lakhrissi B. Corrosion inhibition performance of newly synthesized 5-alkoxymethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives for carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution: experimental, DFT and Monte Carlo simulation studies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018 doi: 10.1039/c8cp03226b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douadi T., Hamani H., Daoud D., Al-Noaimi M., Chafaa S. Effect of temperature and hydrodynamic conditions on corrosion inhibition of an azomethine compounds for mild steel in 1 M HCl solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017;71:388–404. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Inbaraj N.U., Prabhu G.V. Corrosion inhibition properties of paracetamol based benzoxazine on HCS and Al surfaces in 1M HCl. Prog. Org. Coating. 2018;115:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bouoidina A., El-Hajjaji F., Drissi M., Taleb M., Hammouti B., Chung I.M. Towards a deeper understanding of the anticorrosive properties of hydrazine derivatives in acid medium: experimental, DFT and MD simulation assessment. Metall. Mater. Trans. 2018:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Danaee I., Ghasemi O., Rashed G., Avei M.R., Maddahy M. Effect of hydroxyl group position on adsorption behavior and corrosion inhibition of hydroxybenzaldehyde Schiff bases: electrochemical and quantum calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2013;1035:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- 71.El-Hajjaji F., Messali M., Aljuhani A., Aouad M., Hammouti B., Belghiti M., Chauhan D., Quraishi M. Pyridazinium-based ionic liquids as novel and green corrosion inhibitors of carbon steel in acid medium: electrochemical and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;249:997–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar R., Chahal S., Kumar S., Lata S., Lgaz H., Salghi R., Jodeh S. Corrosion inhibition performance of chromone-3-acrylic acid derivatives for low alloy steel with theoretical modeling and experimental aspects. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;243:439–450. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Afia L., Hamed O., Larouj M., Lgaz H., Jodeh S., Salghi R. Novel natural based diazepines as effective corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in HCl solution: experimental, theoretical and Monte Carlo simulations. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2017;70:2319–2333. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng S., Li X., Xie X. Hydroxymethyl urea and 1, 3-bis (hydroxymethyl) urea as corrosion inhibitors for steel in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2014;80:276–289. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kovačević N., Kokalj A. Analysis of molecular electronic structure of imidazole-and benzimidazole-based inhibitors: a simple recipe for qualitative estimation of chemical hardness. Corros. Sci. 2011;53:909–921. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khaled K.F., Amin M.A. Corrosion monitoring of mild steel in sulphuric acid solutions in presence of some thiazole derivatives–molecular dynamics, chemical and electrochemical studies. Corros. Sci. 2009;51(9):1964–1975. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xia S., Qiu M., Yu L., Liu F., Zhao H. Molecular dynamics and density functional theory study on relationship between structure of imidazoline derivatives and inhibition performance. Corros. Sci. 2008;50(7):2021–2029. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mishra A., Verma C., Srivastava V., Lgaz H., Quraishi M.A., Ebenso E.E., Chung I.M. Chemical, electrochemical and computational studies of newly synthesized novel and environmental friendly heterocyclic compounds as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. J. Bio Tribo Corr. 2018;4(3):32. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang D., Xiang B., Liang Y., Song S., Liu C. Corrosion control of copper in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution by domperidone: experimental and theoretical study. Corros. Sci. 2014;85:77–86. [Google Scholar]